Summary

The ebolavirus (EBOV) envelope glycoprotein (GP) is solely responsible for viral attachment to, fusion with, and entry of new host cells, and consequently is a major target of vaccine design efforts. Recently determined crystal structures of key antibodies in complex with their EBOV epitopes have provided insights into the molecular architecture of GP and defined likely hotspots for viral neutralization. In this review, we discuss the structural basis for antibody-mediated neutralization of ebolavirus and its implications for novel therapeutic or vaccine strategies.

Introduction

Ebolavirus (EBOV) is a filamentous, pleiomorphic virus in the family filoviridae. Infection with ebolavirus causes a severe hemorrhagic fever, with 50–90% lethality. Disturbingly, outbreak frequency has increased four-fold in the last decade. Five different species of ebolavirus have been identified: Zaire, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, Reston and Bundibugyo, each named after the location in which the species was first described. All species are lethal to humans, with the possible exception of the rare Côte d’Ivoire species, for which only a single human case has been reported, and the Reston species, which thus far, appears to be non-pathogenic to humans [1,2]. Among these species, Zaire ebolavirus is the most common and the most lethal.

The negative-stranded genome of ebolavirus encodes just seven genes. However, the fourth gene, GP, actually encodes two unique proteins: a non-structural, dimeric secreted glycoprotein, termed sGP, and a trimeric, virion-attached, envelope glycoprotein, termed GP. These two glycoproteins share the first 295 amino acids, but have unique C termini as a result of transcriptional editing. The unique C termini confer different patterns of disulfide bonding, different structures, and different roles in pathogenesis. Approximately 80% of the mRNA transcripts direct synthesis of sGP [3], which is secreted abundantly early in infection [4]. The remaining 20% of the mRNA transcripts direct synthesis of GP. The unique C terminus of GP encodes a heavily glycosylated mucin-like domain, a transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail. Trimeric GP is thus embedded in the viral surface, in contrast to the secreted sGP. Indeed, GP is the only virally encoded protein on the virion surface, and is solely responsible for recognition and entry of new host cells [5–7].

Survival of ebolavirus infection appears to depend on the ability of the host to mount an early and strong immune response. Studies in three separate outbreaks suggest that fatal infection is associated with a poor immune response as measured by low levels of interferon-γ, CD8+ T-cells and antibodies [8,9]. By contrast, nonfatal cases have been associated with a strong inflammatory response and higher levels of antibody [8–11]. Furthermore, in a murine model, short-term control of the virus can be achieved by CD8+ T-cells alone, but long-term control requires the presence of antibodies and CD4+ T-cells [12].

Development of neutralizing antibodies in the context of natural infection may be difficult. Even those people that survive ebolavirus infection often have low to insignificant titres of such antibodies [7,10]. It has been suggested that sGP and shed GP may act as decoys by binding to any neutralizing antibodies [4,13,14]. Indeed, antibodies found in survivor sera appear to preferentially recognize secreted sGP over virion-surface GP [15]. Antibodies specific to sGP are probably non-neutralizing as they do not recognize the virus itself. Antibodies that cross-react between sGP and GP may neutralize, but may not be as effective in vivo, as they may be absorbed by the much more abundant sGP. It is possible that those antibodies specific for viral surface GP may offer the best protection, and hence, structural analysis of GP-specific epitopes has a particular importance.

It is clear that when such antibodies are elicited by vaccination, they do neutralize ebolavirus in vitro and contribute to protection against lethal ebolavirus challenge [16–19]. Further, transfer of sera containing neutralizing antibodies has, anecdotally, conferred some protection, but other explanations for recipients’ survival have also been proposed [20,21]. It is not yet clear which epitopes on GP (or sGP) are targeted by these successful polyclonal sera. However, several monoclonal antibodies against GP have been described. Completion of the crystal structure of ebolavirus GP has now provided a framework for analysis of the epitopes of these monoclonal antibodies, and has suggested new epitopes that could be targeted in immunotherapeutic development [22]. In this review, we describe the structural basis of antibody recognition of trimeric Zaire ebolavirus GP and map known epitopes across its surface.

Overall EBOV glycoprotein structure

The ebolavirus glycoprotein (EBOV GP) is synthesized as a 676-amino acid precursor that is post-translationally cleaved by furin to yield two subunits, termed GP1 and GP2. The two subunits remain covalently attached through a disulfide bond between Cys53 in GP1 and Cys609 in GP2. GP1 is responsible for viral attachment and contains the putative receptor binding site, as well as a heavily glycosylated mucin-like domain. GP2 contains the protein machinery responsible for the fusion of the viral and host cell membranes as well as a hydrophobic internal fusion loop and two heptad repeat regions (HR1 and HR2). After post-translational modification, each EBOV GP monomer (a complex between GP1 and GP2) is ∼150 kDa in size. Three monomers oligomerize to form a non-covalently attached trimer (∼450 kDa) on the viral surface. During infection, the metastable, prefusion conformation of GP transforms into a low energy, stable, six-helix bundle, post-fusion conformation. The post-fusion, six-helix bundle structure of GP2 was crystallographically defined in 1998 [23,24].

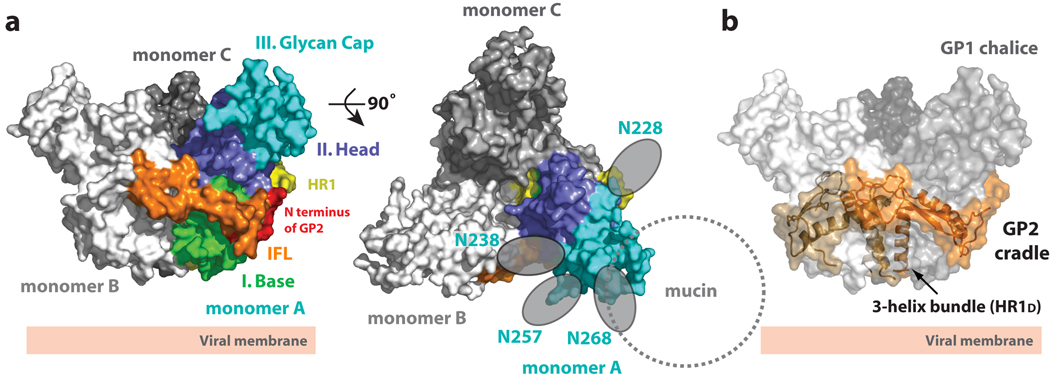

We have recently determined the crystal structure of the prefusion conformation of ebolavirus GP. Here, trimeric GP was crystallized [25] in complex with a neutralizing antibody derived from a human survivor of the 1995 Kikwit, Zaire outbreak [22]. The overall EBOV GP trimer adopts a chalice-like shape (95 × 95 × 70 Å), composed of three non-covalently attached monomers (A, B and C) (Figure 1a). In the trimer, the three GP1 subunits together form a bowl-like chalice and the three GP2 subunits wrap around GP1 to form a cradle (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Overall structure of EBOV GP.

(a) Molecular surface of the GP trimer viewed on its side and down its three-fold axis. Monomer A is colored according to its subdomains: GP1 base- green; GP1 head- blue; GP1 glycan cap- cyan; GP2 N-terminus- red; GP2 internal fusion loop- orange; and GP2 HR1- yellow. (b) Molecular surface of the EBOV GP chalice and cradle. Three lobes of GP1, shown in shades of gray, form the GP chalice, and three subunits of GP2 (orange) wrap around the base of the chalice to form the cradle. Adapted from [22].

EBOV GP1 can be divided into three subdomains: (I) base, (II) head and (III) glycan cap (Figure 1a). The base subdomain (I) forms a hydrophobic concave surface that clamps GP2, likely preventing the GP2 HR1A helix from springing into its fusion-active state prematurely. The head subdomain (II), centrally located between the base and glycan cap, contains the putative receptor-binding site (RBS). This subdomain forms a four-stranded, mixed β-sheet flanked by an α-helix and a smaller, two-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet. Two intramolecular disulfide bonds stabilize the head subdomain. The glycan cap (III), is furthest from the viral surface (closest to the target host cell) and contains four clustered N-linked glycosylation sites (N204, N238, N257 and N268) in an α/β dome over the GP1 head subdomain.

Our structure, combined with carbohydrate sequence analysis, predict that the twelve clustered glycans, of the three glycan caps in the trimer, probably form a carbohydrate canopy across the top of GP. The carbohydrate canopy is probably further extended by the heavily glycosylated mucin-like domain (excised for crystallization). Indeed, the mucin-like domain incorporates another 5 N-linked and 12–17 O-linked glycans onto its ∼150 amino acids. Hence, the glycan cap and mucin-like domain, coupled with additional N-linked glycans on the sides and base of GP, probably combine to form a thick glycan cloak over most of the three-dimensional surface of GP. This thick cloak likely shields much of GP from immune surveillance.

GP2 is highly conserved in sequence and contains a hydrophobic internal fusion loop, a CX6CC cysteine motif and two helical heptad repeat regions (HR1 and HR2). The internal fusion loop (residues 511–556) displays a partially helical hydrophobic region (L529, W531, I532, P533, Y534 and F535) at the end of a disulfide-stabilized, antiparallel β-stranded scaffold that interestingly, wraps around the outside of the GP trimer (Figure 1b). In the prefusion conformation of GP, the hydrophobic fusion residues are sequestered from solvent by packing into a pocket on a neighbouring GP1 monomer. Interestingly, the architecture of the internal fusion loop is different from that of functionally equivalent regions of other class I glycoproteins (like influenza HA [26] parainfluenza virus 5 F [27]). Instead, it more closely resembles fusion structures observed in class II and class III glycoproteins (like flavivirus glycoprotein E [28], vesicular stomatitis virus protein G [29] and herpes simplex virus 1 glycoprotein gB [30]). The HR1 region of EBOV GP can be divided into four segments: HR1A, HR1B, HR1C and HR1D that together assemble a cradle encircling GP1. HR2 and the CX6CC motif that connects HR1 to HR2 are disordered in this structure, perhaps reflecting functionally important flexibility.

Requirements for viral entry

Initial attachment of enveloped viruses to host cells is typically mediated through the viral envelope glycoprotein. Having attached to the host cell, the virus must penetrate the host plasma membrane of the cell and release its genome into the cellular environment for subsequent replication. In these processes, the fusion protein or subunit often undergoes substantial structural rearrangement to appose and fuse the viral and cellular membranes. Prior to these conformational changes, the receptor-binding subunit (GP1 or equivalent) often serves as a clamp on the prefusion, metastable conformation of the fusion subunit (GP2 or equivalent). Receptor binding, low pH, or another mechanism then cause release of the GP1 constraints on GP2, and thus trigger the conformational change required for membrane fusion (as reviewed in [31–33]).

Entry of ebolavirus

The viral entry process in ebolavirus is not well understood, and a clear cellular receptor for entry has yet to be identified. DC-SIGN/L-SIGN, hMGL, β-integrins, folate receptor-α, and Tyro3 family receptors (Axl, Dtk and Mer) have been implicated as cellular factors, but none of these proteins are both necessary and sufficient for viral entry [34–38]. The crystal structure, combined with extensive site-directed mutagenesis [39–41] and truncation studies [42], together predict a functionally important, 10 × 15 Å site located inside the GP1 chalice bowl to be the binding site for a critical host factor or receptor. Indeed, clustered mutations here were subsequently shown to abrogate cell attachment [43]. Interestingly, this putative receptor-binding site may be poorly accessible on the viral surface as it is likely masked by the glycan cap and mucin-like domain on intact GP. Instead, this site may become exposed or better exposed after entry into the endosome.

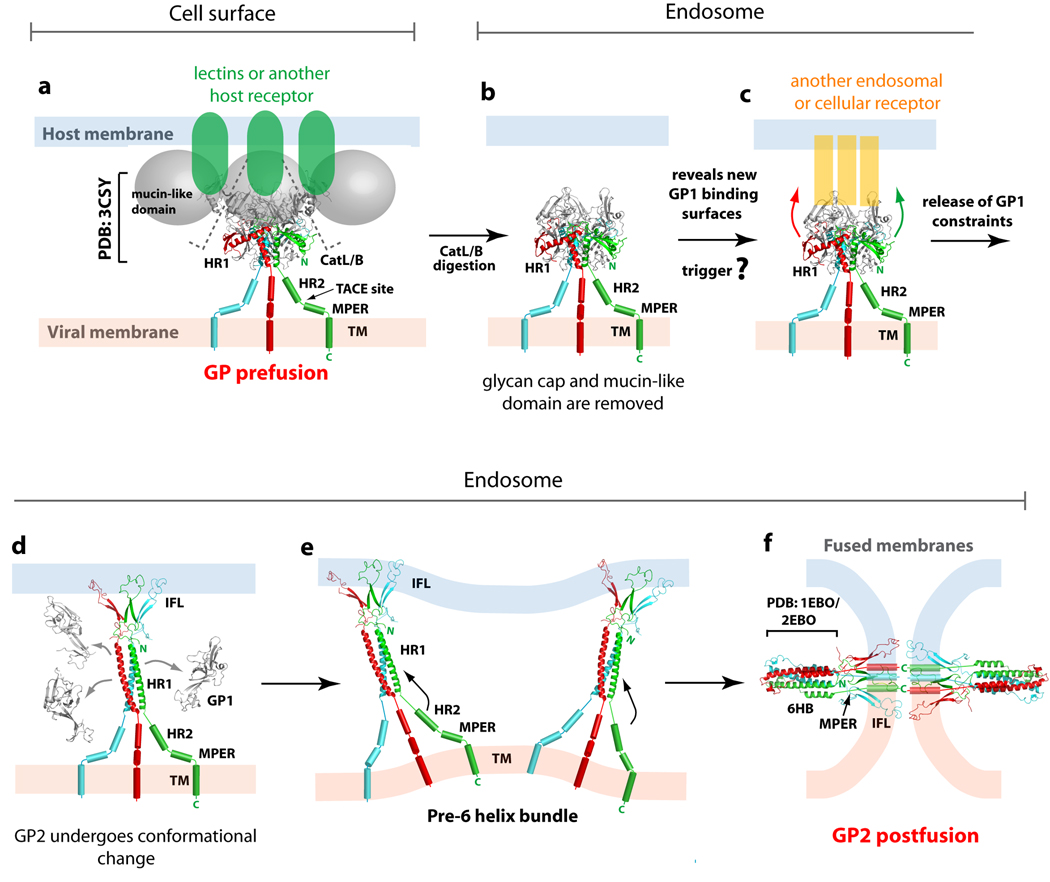

In the host endosome, GP is cleaved by the proteases cathepsin L and/or B [44–46], at or around residue 190 [43] (Figure 2). This cleavage yields a ∼19 kDa fragment of GP1 devoid of the mucin-like domain and glycan cap [43] that displays enhanced binding and infectivity [44–46]. Perhaps removal of the glycocalyx may expose the receptor-binding site on GP1 to another host factor or receptor in the endosome. This as yet unidentified factor may be the required trigger of GP1 release and GP2 conformational change. Comparison of prefusion [22] and postfusion [23,24] crystal structures of GP2 illustrates how the four segments of HR1A-D must unwind from their prefusion ring around GP1, straighten, and assemble into a single 44-residue helical rod. In this process, the rotational and translational movement of HR1A and HR1B position the internal fusion loops at the top of the trimeric GP2. The hydrophobic residues of the internal fusion loop are then able to penetrate the host plasma membrane. In the process, the internal fusion loop may rearrange from the pseudo-helix conformation observed as packed into the GP oligomer [22], to the 310 helix conformation described by NMR studies of the free fusion peptide in sodium dodecyl sulfate micelles or detergent-resistant membrane fractions [47]. After rearrangement of HR1, our model predicts that GP2 will flex at its elbow-like hinge, allowing HR2 to bind alongside HR1 to yield the final postfusion 6-helix bundle. As a result, the internal fusion loop and transmembrane domain become juxtaposed, facilitating fusion of the host and virus plasma membranes. A movie of the EBOV GP-mediated fusion process can be found at www.nature.com/nature/journal/v454/n7201/index.html.

Figure 2. Ebolavirus GP-mediated entry.

Ebolavirus is thought to enter cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis (a) Initially, the metastable, prefusion EBOV GP may bind low affinity lectins or another unidentified receptor at the cell surface for viral attachment. (b) Subsequently, Ebolavirus is internalized and trafficked to the endosome, where host cathepsins cleave GP to remove the glycan cap and mucin-like domain. (c) The newly exposed surface may allow either tighter binding to the host surface receptor or binding to a second cellular factor or receptor in the endosome that could then trigger conformational changes in the GP2 fusion subunit. (d) Structural rearrangements in GP2 allow HR1 to form a single 44-residue helix and position the internal fusion loop for insertion into the host endosomal membrane. Upon insertion in the host membrane, the internal fusion loop adopts a 310 helix. (e) Based on studies in the influenza virus, more than one trimer of GP2 may be required during the membrane fusion process. (f) The formation of the low energy 6-helix bundle (6HB) requires HR2 and MPER to swing from the viral membrane towards the host membrane and pack against the trimeric bundle of HR1. These rearrangements juxtapose the EBOV GP’s internal fusion loop and transmembrane domain, thus facilitating the fusion of the host and viral membranes. This figure is adapted from [22].

In summary, functionally important regions of GP1 include the base subdomain that clamps GP2, the head subdomain that contains a putative receptor binding site, the cathepsin-cleavage loop that links the base subdomain to the glycan cap and the mucin-like domain. Important regions of GP2 include an internal fusion loop packed on the outside of the trimer and two heptad repeats involved in fusion-related conformatioal change. Any of these sites might make effective antibody epitopes.

Antibody response against EBOV GP

However, analysis of the antigenic structure of EBOV GP reveals that most of the protein surface is shielded from humoral immune surveillance by a thick coating of N-linked glycans on both GP1 and GP2. The few sites left exposed include a region at the base of the chalice where GP1 meets GP2, the paddle shape of the internal fusion loop on the outside of the trimer, and short linear stretches of polypeptide between glycans in the mucin-like domain. HR2 and the putative receptor-binding site might also be partially or temporally exposed to antibody, although that is unclear as these regions are missing from the structure. HR2 is disordered in this crystal structure and the mucin-like domain, which might cap the receptor-binding site, had to be excised from GP for crystallization.

Importantly, several monoclonal anti-Ebola antibodies have been identified that demonstrate neutralization in vitro and/or protection in rodent models [48–50]. The epitopes of these anti-Ebola neutralizing antibodies have now been determined by X-ray crystallography or linear peptide dot blots, or suggested by isolation of neutralization escape mutants. We now map these neutralizing antibodies to EBOV GP and propose potential mechanisms of neutralization (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Table 1.

Protective and/or neutralizing antibodies against Ebolavirus GP

| mAb | Isotype | Specificitya | Epitope | Efficacy (−1 day) | Efficacy (+1 day) | Efficacy (+2 days) | Efficacy (non-human primates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murine | |||||||

| 13F6-1-2 | lgG2a | Z;GP1 | Linear; 401–417 | 10/10b | 10/10b | 3/10b | n.d. |

| 6D8-1-2 | lgG2a | Z;GP1 | Linear; 389–405 | 10/10b | 10/10b | 6/10b | n.d. |

| 12B5-1-2 | lgG1 | Z;GP1 | Linear; 477–493 | 6/10b | 8/10b | 1/10b | n.d. |

| 13C6-1-1 | lgG2a | Z, S, IC; GP, sGP | Conformational | 10/10b | 10/10b | 8/10b | n.d. |

| 6D3-1-1 | lgG2a | Z, IC; GP, sGP | Conformational | 9/10b | 10/10b | 9/10b | n.d. |

| 133/3.16 | lgG1 | Z;GP2 | Conformational | 7/8b | n.d. | 7/8b | n.d. |

| 226/8.1 | lgG1 | Z;GP1 | Conformational | 6/8b | n.d. | 7/8b | n.d. |

| Human | |||||||

| KZ52 | lgG1 | Z, GP | Conformational | 5/5c | 4/5c | n.d. | 0/4d |

n.d.= not determined

Note: many other mAb have been raised against GP and sGP [15,48,53], but have not been yet tested for neutralization in vitro and/or protection

specificity to various ebolavirus species: Z= Zaire, S= Sudan, IC= Cote d’lvoire. Note: Bundibugyo ebolavirus was not tested and affinity to each species varied. GP=virion-attached glycoprotein, sGP= non-structural, secreted glycoprotein

number of BALB/c mice surviving challenge with Zaire ebolavirus when 100 µg of mAb is administered

number of guinea pigs surviving challenge with Zaire ebolavirus when 25 mg/kg of mAb is administered

number of rhesus macaques surviving challenge with Zaire ebolavirus when 50 mg/kg of mAb is administered − and +4 days with 2 doses of mAb

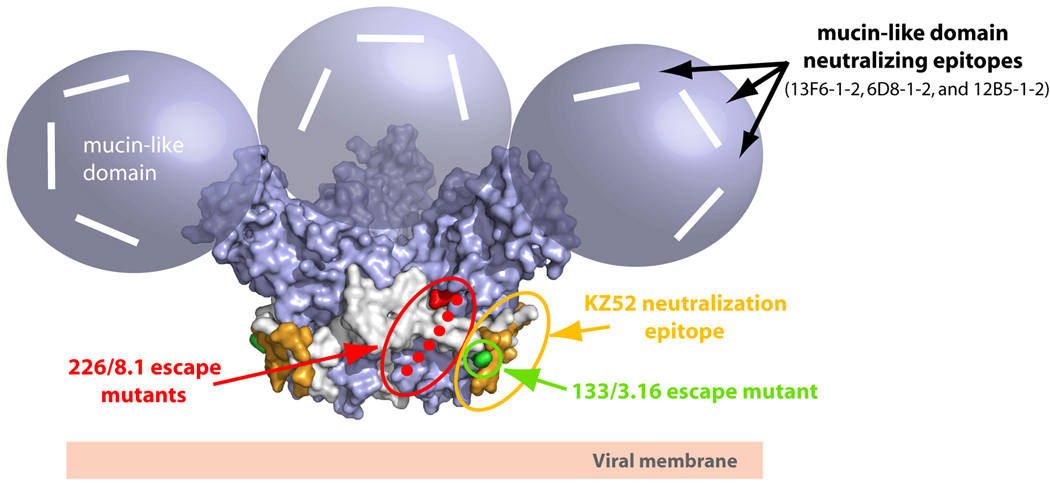

Figure 3. Locations of neutralizing epitopes on EBOV GP.

The locations of the Zaire ebolavirus neutralizing antibodies are mapped onto the molecular surface of the prefusion EBOV GP structure. In general, there are at least three regions on EBOV GP which have elicited neutralizing or protective epitopes. The KZ52 neutralizing epitope, which likely overlaps with mAb 133/3.16 (green), is located at a non-neutralizing site at the base of the EBOV GP chalice (colored in orange). This epitope is primarily composed of GP2 residues 505–514 and 549–556. A second neutralizing epitope termed 226/8.1 (colored red) is centered in the vicinity of the cathepsin cleavage site around residues 134, 194 and 195. The loop between residues 189–213 is disordered in the crystal structure and is shown as green dots. The mucin-like domain is the site of at least three linear neutralizing epitopes (modeled as white lines). These three linear neutralizing epitopes (residues 401–417, 389–405 and 477–493) map to unstructured and non-glycosylated regions on the mucin-like domain.

GP1/GP2-directed antibodies: KZ52 and 133/3.16

One of the more promising antibodies for ebolavirus was identified from the bone marrow of a human survivor of the 1995 Kikwit, Zaire outbreak (Zaire ebolavirus species). This mAb, termed KZ52, neutralizes Zaire ebolavirus in vitro [48] and offers protection from lethal EBOV challenge in a rodent model [51], although it was non-protective in non-human primates [52]. KZ52 is the only mAb yet tested in nonhuman primate protection studies, and so we do not yet know if this result pertains to all anti-EBOV mAbs or if it is unique to KZ52. For example, it may be that the particular epitope of KZ52 is not well-exposed in natural infection. Alternatively, because a single viral particle can be lethal for a primate, it may be too difficult for any single mAb, whatever its epitope, to neutralize every single viral particle and provide sterile protection. Perhaps a cocktail of mAbs against several unique epitopes might confer improved protection over KZ52 administration alone. If so, it will be important to identify multiple, unique antibody epitopes on ebolavirus GP that could be combined into a cocktail, including and in addition to KZ52.

KZ52 is specific for the complex of GP1 and GP2 together. It does not bind GP1 or GP2 expressed individually, nor does it bind sGP. Our crystal structure illustrates that KZ52 binds to the previously described vulnerable, non-glycosylated site at the base of the GP chalice. Its epitope is conformational in nature, specific to the prefusion conformation of GP2 that is wrapped around GP1, and comprised of 80% GP2 and 20% GP1 by buried surface. Interestingly, KZ52 is the first antiviral antibody to be described that bridges the receptor-binding and fusion subunits of any viral glycoprotein. For example, in HIV-1, multiple antibodies are known against gp120 and multiple antibodies are known against gp41, but none have yet been described that bridge gp120 and gp41 together.

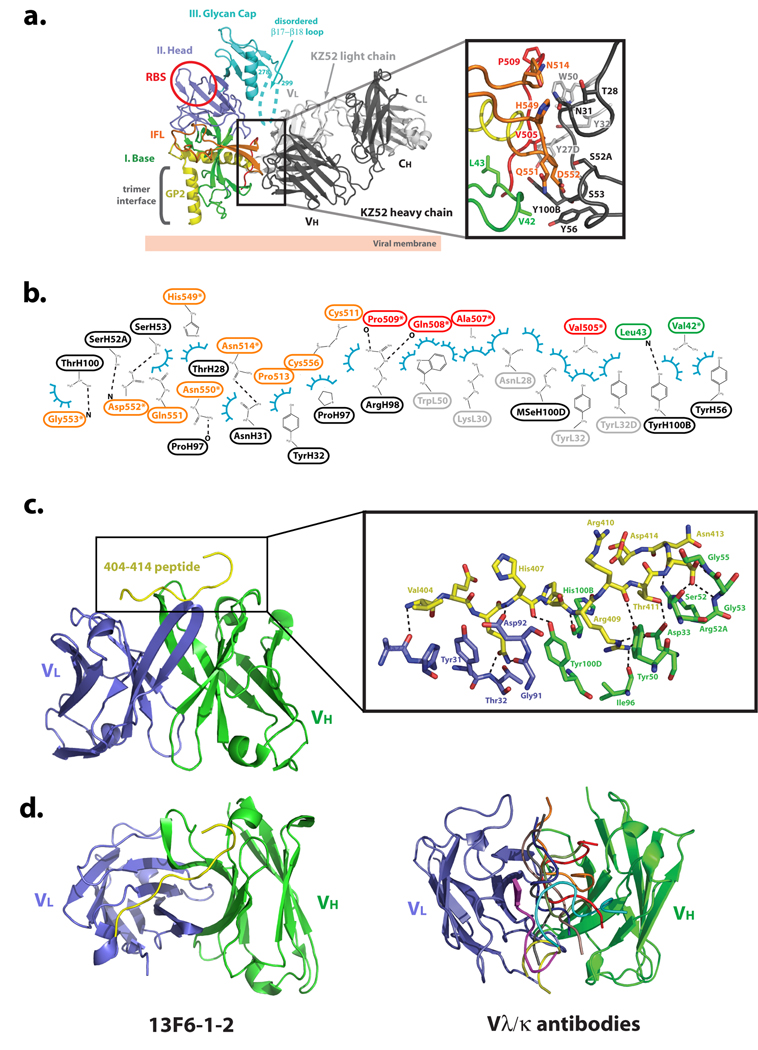

Specifically, KZ52 bridges three discontinuous regions of GP1 and GP2: GP1 residues 42–43, GP2 residues 505–514 (N-terminal region released by furin cleavage) and GP2 residues 549–556 (base of the internal fusion loop) (Figure 4a and Figure 4b). The GP2 sequences among these (residues 505–514 and 549–556) are poorly conserved among ebolaviruses, thus explaining the Zaire species-specificity of KZ52.

Figure 4. EBOV GP-neutralizing antibody interactions.

(a) EBOV GP-KZ52 interactions. KZ52 recognizes a discontinuous epitope at the base of the EBOV GP chalice, and bridges the N terminus and internal fusion loop of GP2 to the N terminus of GP1. One EBOV GP monomer is colored and labeled according to Figure 1a and the Fab heavy and light chains are colored in black and gray, respectively. Selected side-chain interactions at the GP-KZ52 interface are magnified in the inset box. Note that in the wild-type Zaire ebolavirus sequence, position 42 contains a threonine, rather than the valine mutant used here for crystallization. (b) 2-D schematic of the interactions between EBOV GP and KZ52. Van der Waals interactions are illustrated by blue semi-circles and hydrogen bonds by dashed lines. (c) EBOV GP-13F6-1-2 interactions. 13F6-1-2 utilizes a rare Vλx light chain and in contrast to other antibody-peptide interactions, the EBOV GP peptide epitope of 13F6-1-2 binds in a diagonal fashion, recognizing an unstructured, non-glycosylated linear epitope corresponding to residues 404–412 in the mucin-like domain. The EBOV GP peptide is colored in yellow and 13F6-1-2 heavy and light chains are colored in green and blue, respectively. (d) Comparison of peptide binding orientations in Vθ/Vκ and Vλx-containing antibodies. Left panel, the peptide binding to the Vλx-containing 13F6-1-2 antibody (PDB code: 2QHR) is shown in yellow. Right panel, the light and heavy chains of Vλ/Vκ antibodies were superimposed, but for clarity only the peptides are shown (PDB code: 1CU4, red; 1TJG, brown; 1F58, blue; 1ACY, green; 1NAK, yellow; 1SM3, magenta; 1GGI, cyan; 1CFN, orange; and 1CE1, black). This figure is adapted from [22,54].

KZ52 forms van der Waals contacts to GP1 via a main-chain nitrogen of Leu43 and a side-chain carbon of Val42. Note that Val42 is the site of the Thr to Val mutation required to delete a particular N-linked glycan sequon, and improve diffraction. However, the side-chain carbon bound by KZ52 is in common between Val and Thr residues, and hence, the observed contact probably mimics that formed by wild-type GP (certainly KZ52 appears to bind Thr42Val GP as well as wild-type GP). Although contacts to GP1 are present, they are more limited in number than those to GP2 and are somewhat weaker in nature (van der Waals). Hence, it is possible that the requirement of GP1 for KZ52 binding is for maintenance of the GP1 base subdomain clamp on the prefusion conformation of GP2 than provision of direct binding energy. Indeed, KZ52 does not recognize GP in which the GP1-GP2 disulfide bond has been reduced and the clamp released, nor does it recognize the postfusion, 6-helix bundle conformation of GP2.

Importantly, KZ52 may not be the only neutralizing antibody directed towards this epitope. A murine antibody, termed 133/3.16, neutralizes and protects mice (5/5) from a lethal challenge of Ebolavirus even two days post-exposure [18]. Treatment of guinea pigs with 133/3.16 was not as effective in protection as in the mouse model, but single dose treatment of guinea pigs one or two days post-challenge did prolong survival and offer protection in some guinea pigs [18]. This antibody recognizes a conformation-dependent epitope, and neutralization escape assays identified a common single amino acid substitution at His549 in GP2 in all escape variants [49]. In KZ52, His549 and residues in its vicinity form interactions to the antibody heavy chain (Figure 4a). We speculate that the binding interface of the 133/3.16 mAb could overlap with the KZ52 epitope, thus potentially identifying a vulnerable shared epitope and potential “sweet spot” for neutralization (Figure 3).

Antibodies may neutralize at various steps in the viral lifecycle and could: (a) block attachment to the host cell, (b) interfere with virion internalization, (c) block the binding of additional cellular co-factors, (d) inhibit membrane fusion, (e) destabilize the virion structure, (f) aggregate virions, or (g) inhibit postfusion events. The exact mechanism(s) of neutralization by KZ52 and 133/3.16 are not fully understood. However, based on the structure, the binding of KZ52 to primarily GP2 residues suggests a role in preventing the conformational changes required in this subunit during membrane fusion. Alternatively, it is possible that the binding of an IgG KZ52 to GP may sterically block the interaction site of a cofactor required for attachment or cleavage.

GP1-directed antibodies

A unique antibody, termed 226/8.1, was shown to confer protection in mice by a single passive immunization of 100 µg of antibody given one day before or two days after challenge [18]. Three neutralization escape variants reveal single amino acid substitutions at structurally proximal, but non-contiguous residues 134, 194 and 199 of GP1, suggesting that this antibody recognizes a conformation-dependent epitope [49]. The crystal structure of EBOV GP illustrates that residue 134 is located on the β8-β9 loop and that residues 194 and 199 reside in a nearby, disordered loop on the surface of the GP, approximately 15–20 Å from the KZ52 binding site. The disordered loop containing residues 194 and 199 has been confirmed to be the site of cathepsin cleavage [43]. Cleavage here by cathepsins B and L yields a 20 kDa GP1 intermediate that contains residues 33–200. This intermediate is further cleaved to yield the primed 19 kDa GP1 species consisting of residues 33–190. It is interesting to speculate whether mAb 133/3.16 confers protection by blocking cathepsin cleavage of GP.

Two other mAbs, 13C6-1-2 and 6D3-1-1, recognize conformation-dependent epitopes shared between sGP and GP [50]. These sites have not yet been mapped and no escape mutants are known.

An additional series of mAb were generated using ebolavirus-like particles with full length GP, and subfragments of GP1 [53]. These recombinantly expressed and refolded subfragments are polypeptide sequences ∼60–80 residues in size taken from the head, glycan cap and mucin-like subdomains [53]. Antibodies raised against these polypeptides have been characterized for epitope specificity, but not neutralization potential. Interestingly, a subset of these antibodies interacts with either linear or conformation-dependent GP1 epitopes encompassing the cathepsin-cleavage region. MAb P129.2H11 interacts with GP1 residues 157–211 and P129.5F12, P129.4C11 and P129.3H8 recognize an epitope consisting of residues 157–211 and 311–369. Among residues 157–211, the first 30 (residues 157–187) are buried inside the base and head subdomains and thus likely not accessible to antibody. However, the next 25 residues (188–213) reside in a solvent-exposed, disordered loop that contains the cathepsin cleavage site. It is likely that the antibodies against this region (P129.2H11, P129.5F12, P129.4C11 and P129.3H8) have epitopes that overlap that of mAb 226/8.1.

Antibodies directed against the mucin-like domain

The mucin-like domain is predicted to be largely unstructured and highly N- and O-linked glycosylated. A series of antibodies have been identified that react with linear polypeptide sequences contained between glycans in this domain [50]. These linear-epitope antibodies can be divided into three competition group (Table 1). Group 1, which includes the antibody 13F6-1-2, is directed against GP1 residues 401–417. Group 2, which includes the antibody 6D8-1-2 is directed against GP1 residues 389–405, and group 3, which includes the antibody 12B5-1-1, is directed against GP1 residues 477–493. Note that the sequence of the mucin-like domain is highly variable among species of ebolavirus, and hence, 13F6-1–2, 6D8-1–2, and 12B5-1-1 are all specific for the Zaire species. Importantly, many of these antibodies provide complete or partial protection in viral challenge experiments. For example, 10/10 mice survive challenge with 300 times the lethal dose of ebolavirus when 100 µg of mAb 13F6-1-2 is administered one day after challenge [50].

We determined the crystal structure of the competition group 1 mAb, termed 13F6-1-2 (murine IgG2a), in complex with its linear glycoprotein epitope contained within the Zaire ebolavirus GP mucin-like domain (VEQHHRRTD, amino acids 404–412; Figure 4c) [54]. 13F6-1-2 utilizes an extremely rare antibody light chain termed Vλx that confers noncanonical structures to all three light chain complementarity determining regions (CDR), and may confer an unusual mode of binding. In contrast to other Fab-peptide structures in which the peptide binds in a central, vertical groove between heavy and light chains [54] (like a hot dog in a bun), the ebolavirus GP peptide binds diagonally across the 13F6-1-2 combining site (Figure 4d). The peptide adopts a linear, extended conformation lacking any secondary structural elements. 5 hydrogen bonds are formed to the Vλx light chain, and 15 hydrogen bonds are formed to the antibody heavy chain by the GP peptide. In addition, Arg409 of GP1 makes a salt bridge to Asp33 of the 13F6-1-2 heavy chain.

The linear epitopes of competition groups 2 and 3, residues 389–405 and 477–493, could be extended in structure as well. No secondary structure is predicted for residues 389–405, and a single β strand is predicted for residues 477–493. These antibody epitopes do not contain any predicted N- or O-linked glycosylation sites, suggesting that even though the mucin-like domain is heterogeneously glycosylated with N- and O-linked glycans, key peptide epitopes that elicit protective antibodies can be contained within this region.

For viruses such as HIV-1, that cause a chronic infection of constantly evolving viral sequence, antibodies against heavily glycosylated, variable loops of the glycoprotein are less desired, as the virus is able to mutate these sequences and escape immune recognition. However, for ebolavirus, such antibodies should not be discounted. Individual species of ebolavirus are temporally stable in sequence, even within the mucin-like domain (1976 Zaire ebolavirus is 98% identical to 1996 Zaire ebolavirus, 20 years later) [4]. Further, ebolavirus infection of humans and nonhuman primates is rapid and acute, rather than chronic. Unlike HIV-1, ebolavirus infection may have largely resolved itself or killed the host before host antibody has had a chance to exert any selective pressure. As the mucin-like domain probably dominates much of the surface of ebolavirus GP, antibodies that bind well to this region may be quite successful in blocking GP attachment to target cells. Further, these epitopes, on the apical surface of the GP spike, may be better exposed for antibody binding on a densely packed virion than epitopes such as KZ52, which are buried at the bottom of the GP spike.

Conclusions

Significant advances have been made in understanding the overall structure and mechanisms of ebolavirus GP-mediated entry. However, many questions still remain: (i) What are the mechanisms of neutralization of antibodies against GP? (ii) Does the mechanism of neutralization vary by epitope? (iii) Do antibodies against certain epitopes confer superior protection? (iv) Why does KZ52 confer protection in rodent models but fail to protect non-human primates? (v) Would another mAb, or a cocktail of mAbs confer better protection than KZ52 alone in the non-human primate? Additional structures of GP-antibody complexes, coupled with functional analysis, should explain the mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization and protection. Such studies will provide templates for the design and targeting of specific structural GP epitopes and development of novel or improved protective antibodies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to apologize to all authors whose work we were not able to reference due to space limitations. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Dennis Burton and members of the Ollmann Saphire lab for helpful discussions. E.O.S. is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (AI053423 and AI067927), a Career Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology. JEL is supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests. This is manuscript #20086 from Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jahrling PB, Geisbert TW, Dalgard DW, Johnson ED, Ksiazek TG, Hall WC, Peters CJ. Preliminary report: isolation of Ebola virus from monkeys imported to USA. Lancet. 1990;335:502–505. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90737-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le GuennoB, Formentry P, Wyers M, Gounon P, Walker F, Boesch C. Isolation and partial characterisation of a new strain of Ebola virus. Lancet. 1995;345:1271–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez A, Yang ZY, Xu L, Nabel GJ, Crews T, Peters CJ. Biochemical analysis of the secreted and virion glycoproteins of Ebola virus. J Virol. 1998;72:6442–6447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6442-6447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanchez A, Trappier SG, Mahy BW, Peters CJ, Nichol ST. The virion glycoproteins of Ebola viruses are encoded in two reading frames and are expressed through transcriptional editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3602–3607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldmann H, Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Klenk HD. The glycoproteins of Marburg and Ebola virus and their potential roles in pathogenesis. Arch Virol Suppl. 1999;15:159–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6425-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldmann H, Volchkov VE, Volchova VA, Stroher U, Klenk HD. Biosynthesis and role of filoviral glycoproteins. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:2839–2848. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez A, Khan AS, Zaki SR, Nabel GJ, Ksiazek TG, Peters CJ. Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola viruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1279–1304. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baize S, Leroy EM, Georges-Courbot MC, Capron M, Lansoud-Soukate J, Debre P, Fisher-Hoch SP, McCormick JB, Georges AJ. Defective humoral responses and extensive intravascular apoptosis are associated with fatal outcome in Ebola virus-infected patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:423–426. doi: 10.1038/7422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez A, Lukwiya M, Bausch D, Mahanty S, Sanchez AJ, Wagoner KD, Rollin PE. Analysis of human peripheral blood samples from fatal and nonfatal cases of Ebola (Sudan) hemorrhagic fever: cellular responses, virus load, and nitric oxide levels. J Virol. 2004;78:10370–10377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10370-10377.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Williams AJ, Bressler DS, Martin ML, Swanepoel R, Burt FJ, Leman PA, Khan AS, Rowe AK, et al. Clinical virology of Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF): virus, virus antigen, and IgG and IgM antibody findings among EHF patients in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S177–S187. doi: 10.1086/514321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leroy EM, Baize S, Volchkov VE, Fisher-Hoch SP, Georges-Courbot MC, Lansoud-Soukate J, Capron M, Debre P, McCormick JB, Georges AJ. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. Lancet. 2000;355:2210–2215. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta M, Mahanty S, Greer P, Towner JS, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR, Ahmed R, Rollin PE. Persistent infection with ebola virus under conditions of partial immunity. J Virol. 2004;78:958–967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.958-967.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolnik O, Volchkova V, Garten W, Carbonnelle C, Becker S, Kahnt J, Stroher U, Klenk HD, Volchkov V. Ectodomain shedding of the glycoprotein GP of Ebola virus. Embo J. 2004;23:2175–2184. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Slenczka W, Klenk HD, Feldmann H. Release of viral glycoproteins during Ebola virus infection. Virology. 1998;245:110–119. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maruyama T, Parren PW, Sanchez A, Rensink I, Rodriguez LL, Khan AS, Peters CJ, Burton DR. Recombinant human monoclonal antibodies to Ebola virus. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S235–S239. doi: 10.1086/514280. •This paper describes the first set of human antibodies against Ebolavirus infection, identified in outbreak survivors

- 16.Kudoyarova-Zubavichene NM, Sergeyev NN, Chepurnov AA, Netesov SV. Preparation and use of hyperimmune serum for prophylaxis and therapy of Ebola virus infections. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S218–S223. doi: 10.1086/514294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Sulli NJ, Geisbert JB, Shedlock DJ, Xu L, Lamoreaux L, Custers JH, Popernack PM, Yang ZY, Pau MG, et al. Immune protection of nonhuman primates against Ebola virus with single low-dose adenovirus vectors encoding modified GPs. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takada A, Ebihara H, Jones S, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y. Protective efficacy of neutralizing antibodies against Ebola virus infection. Vaccine. 2007;25:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warfield KL, Bosio CM, Welcher BC, Deal EM, Mohamadzadeh M, Schmaljohn A, Aman MJ, Bavari S. Ebola virus-like particles protect from lethal Ebola virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15889–15894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237038100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mupapa K, Massamba M, Kibadi K, Kumula K, Bwaka A, Kipasa M, Coleblunders R, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ. Treatment of Ebola hemorrhagic fever with blood transfusions from convalescent patients. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:S18–S23. doi: 10.1086/514298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sadek RF, Khan AS, Stevens G, Peters CJ, Ksiazek TG. Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995: determinants of survival. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S24–S27. doi: 10.1086/514311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee JE, Fusco MH, Hessell AJ, Oswald WB, Burton DR, Saphire EO. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature. 2008;454:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nature07082. ••This paper describes the first structure of the prefusion, trimeric Ebolavirus glycoprotein in complex with a neutralizing antibody identified from a human survivor of the 1995 Kikwit, Zaire outbreak and provides a model for Ebolavirus entry and future therapeutic development.

- 23.Weissenhorn W, Carfi A, Lee KH, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the Ebola virus membrane fusion subunit, GP2, from the envelope glycoprotein ectodomain. Mol Cell. 1998;2:605–616. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malashkevich VN, Schneider BJ, McNally ML, Milhollen MA, Pang JX, Kim PS. Core structure of the envelope glycoprotein GP2 from Ebola virus at 1.9-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2662–2667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JE, Fusco MH, Saphire EO. An efficient platform for screening expression and crystallization of glycoproteins produced in human cells. Nature Protocols. 2009;4:592–604. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature. 1981;289:366–373. doi: 10.1038/289366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yin HS, Wen X, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structure of the parainfluenza virus 5 F protein in its metastable, prefusion conformation. Nature. 2006;439:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rey FA, Heinz FX, Mandl C, Kunz C, Harrison SC. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 Å resolution. Nature. 1995;375:291–298. doi: 10.1038/375291a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roche S, Rey FA, Gaudin Y, Bressanelli S. Structure of the prefusion form of the vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G. Science. 2007;315:843–848. doi: 10.1126/science.1135710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heldwein EE, Lou H, Bender FC, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex virus 1. Science. 2006;313:217–220. doi: 10.1126/science.1126548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structural basis of viral invasion: lessons from paramyxovirus F. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. •A thorough and informative review on the three classes of viral membrane fusion proteins and their mechanisms of viral entry.

- 34.Alvarez CP, Lasala F, Carrillo J, Muniz O, Corbi AL, Delgado R. C-type lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. J Virol. 2002;76:6841–6844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6841-6844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan SY, Empig CJ, Welte FJ, Speck RF, Schmaljohn A, Kreisberg JF, Goldsmith MA. Folate receptor-alpha is a cofactor for cellular entry by Marburg and Ebola viruses. Cell. 2001;106:117–126. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimojima M, Takada A, Ebihara H, Neumann G, Fujioka K, Irimura T, Jones S, Feldmann H, Kawaoka Y. Tyro3 family- mediated cell entry of Ebola and Marburg viruses. J Virol. 2006;80:10109–10116. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01157-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takada A, Fujioka K, Tsuiji M, Morikawa A, Higashi N, Ebihara H, Kobasa D, Feldmann H, Irimura T, Kawaoka Y. Human macrophage C-type lectin specific for galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine promotes filovirus entry. J Virol. 2004;78:2943–2947. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.6.2943-2947.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takada A, Watanabe S, Ito H, Okazaki K, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Down regulation of beta1 integrins by Ebola virus glycoprotein: implication for virus entry. Virology. 2000;278:20–26. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brindley MA, Hughes L, Ruiz A, McCray PB, Jr, Sanchez A, Sanders DA, Maury W. Ebola virus glycoprotein 1: identification of residues important for binding and postbinding events. J Virol. 2007;81:7702–7709. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manicassamy B, Wang J, Jiang H, Rong L. Comprehensive analysis of Ebola virus GP1 in viral entry. J Virol. 2005;79:4793–4805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4793-4805.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mpanju OM, Towner JS, Dover JE, Nichol ST, Wilson CA. Identification of two amino acid residues on Ebola virus glycoprotein 1 critical for cell entry. Virus Res. 2006;121:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhn JH, Radoshitzky SR, Guth AC, Warfield KL, Li W, Vincent MJ, Towner JS, Nichol ST, Bavari S, Choe H, et al. Conserved receptor-binding domains of Lake Victoria Marburgvirus and Zaire Ebolavirus bind a common receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15951–15958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dube D, Brecher MB, Delos SE, Rose SC, Park EW, Schornberg KL, Kuhn JH, White JM. The primed ebolavirus glycoprotein (19-kilodalton GP1,2): sequence and residues critical for host cell binding. J Virol. 2009;83:2883–2891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01956-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chandran K, Sullivan NJ, Felbor U, Whelan SP, Cunningham JM. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science. 2005;308:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1110656. • This paper describes the original identification of the essential role for cathepsin B and L in Ebolavirus GP-mediated entry.

- 45.Kaletsky RL, Simmons G, Bates P. Proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoproteins enhances virus binding and infectivity. J Virol. 2007;81:13378–13384. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01170-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schornberg K, Matsuyama S, Kabsch K, Delos S, Bouton A, White J. Role of endosomal cathepsins in entry mediated by the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 2006;80:4174–4178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4174-4178.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freitas MS, Gaspar LP, Lorenzoni M, Almeida FC, Tinoco LW, Almeida MS, Maia LF, Degreve L, Valente AP, Silva JL. Structure of the Ebola fusion peptide in a membrane-mimetic environment and the interaction with lipid rafts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27306–27314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maruyama T, Rodriguez LL, Jahrling PB, Sanchez A, Khan AS, Nichol ST, Peters CJ, Parren PW, Burton DR. Ebola virus can be effectively neutralized by antibody produced in natural human infection. J Virol. 1999;73:6024–6030. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.6024-6030.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takada A, Feldmann H, Stroeher U, Bray M, Watanabe S, Ito H, McGregor M, Kawaoka Y. Identification of protective epitopes on ebola virus glycoprotein at the single amino acid level by using recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses. J Virol. 2003;77:1069–1074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1069-1074.2003. •• This paper in combination with Wilson, et al. (ref. 50) characterizes a series of murine antibodies and identifies its protective epitope on the Ebolavirus glycoprotein.

- 50. Wilson JA, Hevey M, Bakken R, Guest S, Bray M, Schmaljohn AL, Hart MK. Epitopes involved in antibody-mediated protection from Ebola virus. Science. 2000;287:1664–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1664. • This study identifies a series of protective murine antibodies, directed towards five unique epitopes on the Ebolavirus GP, that protect mice against lethal EBOV challenge up to two days post-exposure.

- 51.Parren PWHI, Geisbert TW, Maruyama T, Jahrling PB, Burton DR. Pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis of Ebola virus infection in an animal model by passive transfer of a neutralizing human antibody. J Virol. 2002;76:6408–6412. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6408-6412.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oswald WB, Geisbert TW, Davis KJ, Geisbert JB, Sullivan NJ JahrlingPB, Parren PW, Burton DR. Neutralizing antibody fails to impact the course of Ebola virus infection in monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:62–66. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shahhosseini S, Das D, Qiu X, Feldmann H, Jones SM, Suresh MR. Production and characterization of monoclonal antibodies against different epitopes of Ebola virus antigens. J Virol Methods. 2007;143:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee JE, Kuehne A, Abelson DM, Fusco ML, Hart MK, Saphire EO. Complex of a protective antibody with its Ebola virus GP peptideepitope: unusual features of a V lambda x light chain. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:202–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]