Abstract

Objectives

We examined whether rs4606, a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the translated region at the 3′ end of RGS2, was related to suicidal ideation in an epidemiologic sample of adults living in areas affected by the 2004 Florida Hurricanes.

Methods

We recruited an epidemiologic sample of residents of Florida via random digit-dial procedures after the 2004 Florida Hurricanes; participants were interviewed about suicidal ideation, hurricane exposure, and social support. Participants who returned buccal DNA samples via mail (n=607) were included here.

Results

Rs4606 in RGS2 was associated with increased symptoms of current suicidal ideation (p<0.01). Each ‘C’ allele was associated with 5.59 times increased risk of having current ideation. No gene-by-environment interactions were found, perhaps due to low power.

Conclusions

RGS2 rs4606 is related to risk of current suicidal ideation in stressor-exposed adults.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, suicide, trauma, RGS2, gene association

Suicide remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide; in 2002 alone approximately 877,000 lives were lost to suicide (World Health Organization 2003). Suicidal behavior and suicide have been demonstrated to have a heritable component based on twin (Statham, Heath et al. 1998; Fu, Heath et al. 2002) and adoption (Schulsinger, Kety et al. 1979; Wender, Kety et al. 1986) studies, and the results of family studies have been consistent (Powell, Geddes et al. 2000). Heritability estimates for suicidal ideation are about 43% (Statham, Heath et al. 1998; Fu, Heath et al. 2002), and heritability estimates for suicide attempts range from 30-55%. Although one of the demonstrated risk factors for suicidal behavior and suicide is a major psychiatric disorder (Powell, Geddes et al. 2000), heritability of psychiatric conditions alone does not account for the biologic transmission of suicidal behavior and suicide (Brent and Mann 2005). Data from the Vietnam Era Twin Registry (Fu, Heath et al. 2002) revealed that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts had moderate heritability, even after controlling for psychiatric disorders, combat history, and demographic variables (36% and 17.4%, respectively).

In recent years, molecular genetic studies have aimed to identify genetic variants that confer risk for suicidal behavior. Most studies have focused on genes that code for proteins in the serotonergic system (for review see (Bondy, Buettner et al. 2006). Although several significant associations between suicidal behavior and the serotonergic system have been reported, genes that code for modulators of this system have also recently been studied (Cui, Nishiguchi et al. 2008), such as regulators of G-protein signaling. Regulators of G-protein signaling bind to Gα subunits and increase their GTPase activity, which then attenuates the downstream signaling (Hollinger and Hepler 2002). RGS2 (regulator of G-protein signaling 2), a potent regulator that reduces G-protein activity, selectively inhibits Gqα (Heximer 2004), therefore increasing GTPase activity. Of RGS2 polymorphisms, rs4606 has received the most attention. Rs4606, which maps to the 3′ untranslated region of the RGS2, is of particular interest because it is associated with variation in peripheral blood mononuclear cell and cultured fibroblast RGS2 mRNA expression (Semplicini, Lenzini et al. 2006). Variation in rs4606 has been associated with panic disorder (Leygraf, Hohoff et al. 2006), generalized anxiety disorder (Koenen, Amstadter et al. In Press), and anxiety-related temperament, personality, and brain function (Smoller, Paulus et al. 2008). Recently, the distribution of rs4606 genotypes was found to be significantly different in suicide victims versus comparison subjects (Cui, Nishiguchi et al. 2008).

The present investigation is a secondary analysis of data that was collected to examine prevalence and correlates of mental health phenotypes following a stressor, with the aim of informing the conduct of larger cohort studies. Given previous findings relating RGS2 variation to anxiety and suicide, we hypothesized that rs4606 variation would be associated with suicidal ideation in an epidemiologic sample of older adults who were exposed to one or more hurricanes during the 2004 Florida Hurricane season (Acierno, Ruggiero et al. 2006; Galea, Acierno et al. 2006; Acierno, Ruggiero et al. 2007; Kilpatrick, Koenen et al. 2007). Given our previous findings in this sample indicating that ‘C’ is the risk allele for anxiety disorders (Koenen, Amstadter et al. In Press), we hypothesized that the same direction of risk would be found for suicidal ideation. An exploratory aim of this study was to determine if level of stressor exposure was a moderator of a possible relation between suicidal ideation and RGS2.

Materials & Methods

Data Collection and Sample

This study focuses on the 607 participants in the 2004 Florida Hurricanes Study who completed structured telephone interviews and provided saliva samples that yielded genotype data for the rs4606 polymorphism. More details about the sampling procedure and methodology for the Florida Hurricanes Study are provided elsewhere (Acierno, Ruggiero et al. 2006; Galea, Acierno et al. 2006; Acierno, Ruggiero et al. 2007; Kilpatrick, Koenen et al. 2007). Demographic characteristics of the 607 sample participants were as follows: 35.1% men, 64.9% women; 22.6% ≤ 59 years of age, 77.4% ≥ 60 years of age; 90% white, 3.9% black, 3.9% Hispanic, 1.7% other, 0.5% missing self-report race/ethnicity data.

Verbal consent was obtained from the participants; participants were sent letters documenting the elements of verbal consent and providing them with contact information for the principal investigator. Participants who completed the diagnostic interview and returned saliva samples were paid $20.

Assessment Procedure

Telephone interviews were conducted with a probability sample of adults from telephone households in 38 hurricane-affected counties in Florida within 6–9 months of the 2004 hurricane season, between April 5 and June 12, 2005. The 38 counties each were directly affected by at least one of four hurricanes during the 2004 season (Charley, Frances, Ivan, Jeanne). Sample selection and telephone interviewing via random-digit-dial procedures was performed by AbtSRBI, a survey research firm with substantial experience conducting academic studies (Galea, Ahern et al. 2002). Assessments were conducted via highly structured interview using computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) methodology that allows for considerable quality control.

Suicidal ideation was assessed by the following question from the SCID-IV: “Has there ever been a time of two weeks or longer when you felt things were so bad that you thought about hurting yourself or you would be better off dead?” If this question was endorsed, participants were asked when this occurred. Current suicidal ideation was defined as occurring within the six months prior to the interview, and was endorsed by 3.1% of participants.

Stressor exposure (hurricane exposure for post-hurricane PTSD, lifetime potentially traumatic event [PTE] exposure for lifetime PTSD) and social support were previously found to be associated with PTSD symptom level in this sample (Acierno, Ruggiero et al. 2007) and were therefore included as covariates in the current regression models of post-hurricane symptom count.

Hurricane exposure was assessed with five indicators identified in previous research (Freedy, Saladin et al. 1994) on the basis of their relation to posthurricane mental health functioning: (1) being personally present during hurricane-force winds or major flooding; (2) lack of adequate access to food, water, electricity, telephone, or clothing for a week or longer; (3) losses or significant damage in two or more of five pre-defined categories of hurricane-related loss (i.e., furniture; sentimental possessions; automobile; pets; crops, trees, garden); (4) displacement from home for 1 week or longer; and (5) out-of-pocket (i.e., unreimbursed) losses of $1,000 or more. High hurricane exposure was defined as having experienced two or more of these indicators (44.6% of sample).

PTE exposure was measured using behaviorally specific language that asked if participants had been exposed to five types of events: (1) natural disaster (other than 2004 hurricanes); (2) serious work accident; (3) attacked with a gun; (4) attacked without a weapon; and (5) military combat or being in a war zone and if, during this exposure, they feared that they would be killed or seriously injured: PTE exposure was operationalized as the participant having been exposed to at least one of these potentially traumatic events, and during that time, having an experience of fear that they would be injured or killed (45.0% of sample).

Social support during the six months before the hurricanes was assessed with a modified five-item version of the Medical Outcomes Study module (Sherbourne and Stewart 1991) that assesses emotional, instrumental, and appraisal social support (sample range=0–20; mean=15.9, SD=4.8). Low social support was operationalized as a score of 15 or less (37.0% of the sample) based on the cutoff score derived from prior work (Galea, Ahern et al. 2002). This scale had good reliability (Chronbach's alpha=0.86).

Collection of DNA samples

Saliva samples were obtained via a mouthwash protocol and returned via mail to the Yale University laboratory for DNA extraction and analyses. Saliva samples were provided by 651 participants (42.2% response rate). Of these, valid genetic ancestry data were available for 623 cases (95.7%), and valid genotype data were available for 607 cases (93.2%). The likelihood of submitting a saliva sample did not differ in relation to sex, level of hurricane exposure, level of social support, or PTSD status. Additional details on response rate and correlates of participation are summarized elsewhere (Galea, Acierno et al. 2006).

Genotyping

DNA was extracted from saliva using PUREGENE (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis) kits. SNPs were genotyped with a fluorogenic 5′ nuclease assay method (“TaqMan”) using the ABI PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System (ABI, Foster City, CA, USA). All genotypes were assayed in duplicate; discordant genotypes were discarded. (Our previous study (Koenen et al 2008) included the same genotype data for both RGS2 and the ancestry informative maker panel.)

In addition, 36 markers were genotyped to provide ancestry information (Stein, Schork et al. 2004; Yang, Zhao et al. 2005; Yang, Zhao et al. 2005). We added one additional highly informative single nucleotide polymorphism marker, SLC24A5 (Lamason, Mohideen et al. 2005) to the panel described previously. This marker set has been rigorously shown to differentiate between American populations, and is also very effective at distinguishing Asian populations (Listman, Malison et al. 2007).

Ancestry Proportion Scores

Ancestry proportion scores, a number representing the proportion of genetic inheritance from major parental populations, were generated to avoid spurious associations that can result from variation in allele frequency and prevalence of trait by population. The participants' ancestries were estimated by Bayesian cluster analysis with the marker panel described above on the procedures and STRUCTURE software developed by Pritchard and colleagues (Pritchard and Rosenberg 1999; Falush, Stephens et al. 2003). The STRUCTURE procedure allows for population assignment for participants, estimation of admixture proportions for individuals, and infers the number of parent populations in the sample. For the STRUCTURE analysis, we specified the “admixture” and “allele frequencies correlated” models and used 100,000 burn-in and 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations, as described previously. This procedure generated a proportion score that was used as a regression coefficient in study analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were utilized to produce n's and percentages of all independent variables (Table 1). Chi-squared analyses were conducted to determine whether the rs4606 polymorphism in RGS2 was associated with current suicidal ideation. Next, logistic regressions were conducted to determine whether any observed association persisted after adjusting for sex, age, ancestral proportion scores, and stressor exposure (i.e., low social support, high hurricane exposure, PTE exposure), see Table 2. To determine whether the association between RGS2 and suicidal ideation was modified by level of stress exposure, we tested all higher order interactions between RGS2 genotype and stress exposure variables (social support, hurricane exposure, PTE exposure).

Table 1.

Frequencies for Independent Variables (N=607)

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age | ||

| ≤ 59 years | 137 | 22.8 |

| ≥ 60 years | 465 | 77.2 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 213 | 35.1 |

| Female | 394 | 64.9 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 547 | 90.6 |

| African American | 23 | 3.8 |

| Hispanic | 23 | 3.8 |

| Other | 11 | 1.8 |

| High Hurricane Exposure | ||

| Yes | 271 | 44.6 |

| No | 336 | 55.4 |

| Low Social Support | ||

| Yes | 224 | 37.0 |

| No | 381 | 63.0 |

| PTE Exposure | ||

| Yes | 273 | 45.0 |

| No | 334 | 55.0 |

| RGS2 Genotype | ||

| G/G | 47 | 7.7 |

| C/G | 221 | 36.4 |

| C/C | 339 | 55.8 |

Table 2.

Final Logistic Regression Analysis of the Association between RGS2 Genotype and Current Suicidal Ideation.

| Suicidal Ideation. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

| Female Sex | 4.00 | .89-18.08 | .07 |

| Age greater than 60 years | 2.53 | .89-7.22 | .08 |

| Ancestral proportion score | .12 | .00-11.59 | .37 |

| High hurricane exposure | 1.00 | .36-2.77 | .99 |

| PTE exposure | 1.44 | .52-3.99 | .48 |

| Low social support | 5.92 | 1.88-18.61 | .002 |

| RGS2 rs4606 (‘C’is risk allele) | 5.59 | 1.30-24.09 | .02 |

Results

Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation and RGS2 Genotype

Current suicidal ideation was reported by 3.1% of participants (n=19). RGS2 SNP rs4606 genotype frequencies were consistent with Harvey-Weinberg equilibrium expectations. Genotype frequencies were similar to those reported by Leygraf et al (2006): GG (n=47, 7.7%), CG (n=221, 36.4%, CC (n=339, 55.8%). Self-reported race/ethnicity was associated with the prevalence of suicidal ideation (χ2 [3, n=602]=10.47, respectively, p<.05), with a higher proportion of Hispanic participants reporting suicidal ideation (13.0% of Hispanic participants) than other racial/ethnic groups (0% of African American participants, 2.6% of European-American participants); thus, we included correction based on ancestry coefficients derived from the STRUCTURE analyses (described above) in our analyses to account for possible population stratification.

Association between Suicidal Ideation and RGS2 Genotype

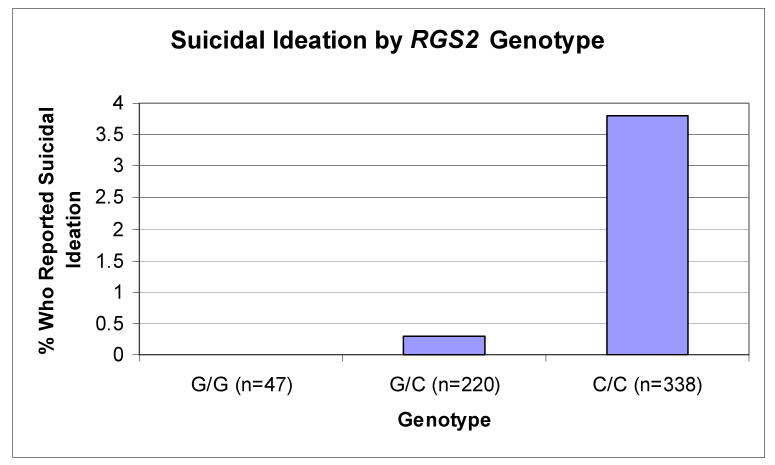

The chi-squared linear-by-linear association test supported a significant association between rs4606 and current suicidal ideation (χ2 [1, n=605]=8.28, p<.01). The dose-response association between rs4606 and suicidal ideation is depicted in Figure 1. Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression analysis. In the main effects model only low social support and RGS2 genotype increased risk for suicidal ideation. Each ‘C’ allele at rs4606 was associated with a 5.59 fold increase risk of having current suicidal ideation. Given previous findings with this data revealing a relation between RGS2 and GAD, a second regression controlling for GAD was conducted, revealing the same pattern of results. Specifically, the relation between RGS2 and suicidal ideation remained significant after controlling for GAD (OR=5.30, 95% CI: 1.93-22.96, p<.05). None of the interaction tests for RGS2 genotype X stress exposure was significant.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Participants by Genotype Who Reported Suicidal Ideation.

Discussion

This is the second paper to date to examine rs4606 in the context of suicidal behavior, and the first to examine the association between rs4606 and suicidal ideation in an epidemiologic sample. Consistent with Cui and colleagues, (Cui, Nishiguchi et al. 2008), we found that rs4606 was associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation. Our association between RGS2 and suicidal ideation was not modified by intensity of stressor exposure. These findings, in conjunction with data showing increased RGS2 immunoreactivity in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex of suicide victims, suggests that RGS2 is involved in the pathophysiology of suicide, perhaps through an alteration of intracellular signal transduction (Cui, Nishiguchi et al. 2008). However, in the present study the ‘C’ allele of rs4606 was associated with increased risk of suicidal behavior, which is not consistent with Cui and colleagues, who reported the ‘G’ allele to be the risk allele. A fully satisfactory explanation for observation of association of opposite alleles with suicide-related traits in different studies is not yet available. Some possible explanations include: (a) the differences in phenotype measurement and definition account for the differences in association; (b) our sample was significantly older than the sample of Cui et al.'s study, and therefore risk variables may vary between older and younger adults and (c) the marker studied (rs4606) is in linkage disequilibrium with a different functional variant, and the direction of LD differs by population. Future studies with larger sample sizes should conduct fine mapping of the 3′ region of RGS2 to further our knowledge of its role in suicidal behavior.

Two other findings in our study warrant mention. First, we identified a possibly modifiable predictor of suicidal behavior: social support. Individuals with low social support were approximately six times more likely to report suicidal behavior than were individuals with high social support. This suggests that facilitation of social networking may be an important intervention area for at risk individuals. Second, although our ancestry proportion scores were not a significant predictor of suicidal behavior in our final model, in our preliminary chi-square analyses, we found that a relatively large proportion of Hispanic individuals were reporting suicidal behavior (13%); however, the actual number of Hispanic individuals reporting ideation was three. Although this number is commensurate with epidemiologic data on suicidal behavior in the general population (Kessler, Borges et al. 1999), this percentage was higher than was found in the other racial/ethnic groups in our study.

The present study may have clinical implications. Each suicide attempt or completion affects many individuals, making this public health problem even more wide spread. Suicide prevention efforts should be focused on those most in need. Although the best predictor of a future suicide attempt is a past attempt (Malafosse 2005), examining other predictors, such as genetic variants that may confer risk, could improve screening and prevention efforts. Early identification of those at risk, followed by aggressive intervention and continued monitoring, may significantly decrease this major public health problem. Biologically informed studies of response to intervention are also warranted. Genetic studies of suicidality may also assist in the understanding of mechanisms underlying vulnerability. This, in turn, may afford discovery of novel pharmacological agents used to treat this condition.

Although the present study has many strengths, one of which is that the present methodology is population-based, notable limitations exist. Suicidal ideation was assessed using a single item. We did not assess for suicide intent or plan, thereby limiting the paper. Additionally, we were unable to distinguish between potential non-suicidal individuals who may be self-injurious. Further, the relatively low prevalence of participants who reported suicidal ideation in this sample resulted in limited power to examine to detect interaction effects or examine the role of other potentially important variables. Additional research is needed to replicate and extend our findings. The present analysis of preliminary data is promising, and suggests that larger cohort studies with a thorough suicide assessment should be conducted to carefully examine the role of RGS2 in suicidal behavior. Further, we suggest that fine mapping of this gene be conducted in future studies. Lastly, given that our negative findings of gene by environment interactions were possibly attributed to low power, and given that stress is a known precipitant of suicidal behavior in at risk individuals (Malafosse 2005), we suggest that future investigations should carefully characterize the environment (e.g., history of stressor exposure, social support, social environment) and examine possible interactions with genetic variants that may together shed light on who is at most risk for suicidal behavior. This research may in turn assist in the identification and intervention/prevention of this large public health concern. In sum, our results suggest that epidemiologic study of this construct is feasible and this methodology may improve power to find gene-phenotype associations for important public health problems such as suicidal behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant MH05220, NIMH and NIN research grant MH07055, and NIDA grant K24 DA15105. Dr. Amstadter is supported by NIMH grant 083469. Dr. Koenen is supported by NIMH grants K08-MH070627 and MH078928.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials: not included

The authors declare no conflicting financial or other competing interests.

References

- Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Galea S, et al. Psychological sequelae resulting from the 2004 Florida hurricanes: implications for postdisaster intervention. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97 1:S103–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Risk and protective factors for psychopathology among older versus younger adults after the 2004 Florida hurricanes. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(12):1051–9. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221327.97904.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondy B, Buettner A, Zill P. Genetics of suicide. Molecular Psychiatry. 2006;11:336–351. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Mann JJ. Family genetic studies, suicide and suicidal behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics; 2005. pp. 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Nishiguchi N, Ivleva E, et al. Association of RGS2 gene polymorphisms wiht suicide and increased RGS2 immunoreactivity in the postmortem brain of suicide victims. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1537–1544. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003;164(4):1567–87. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedy JR, Saladin ME, Kilpatrick DG, et al. Understanding acute psychological distress following natural disaster. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(2):257–73. doi: 10.1007/BF02102947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental influences on suicidality in men. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:11–24. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Acierno R, Ruggiero K, et al. Social context and the psychobiology of posttraumatic stress. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1071:231–41. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al. Psychological sequelae of the september 11 terrorist attacks in new york city. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heximer SP. RGS2-mediated regulation of Gqalpha. Methods in Enzymology. 2004;390:65–82. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger S, Hepler JR. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacological Reviews. 2002;54(3):527–59. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56(7):617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, et al. The serotonin transporter genotype and social support and moderation of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in hurricane-exposed adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1693–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenen KC, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero KJ, et al. Association between RGS2 and generalized anxiety disorder in an epidemiologic sample of hurricane-exposed adults. Depression and Anxiety. doi: 10.1002/da.20528. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamason RL, Mohideen MA, Mest JR, et al. SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans. Science. 2005;310(5755):1782–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1116238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leygraf A, Hohoff C, Freitag C, et al. Rgs 2 gene polymorphisms as modulators of anxiety in humans? Journal of Neural Transmission. 2006;113(12):1921–5. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listman JB, Malison RT, Sughondhabirom A, et al. Demographic changes and marker properties affect detection of human population differentiation. BMC Genetics. 2007;8(21):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malafosse A. Genetics of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics; 2005. pp. 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, Geddes J, Deeks J, et al. Suicide in psychiatric hospital in-patients: Risk factors and their predictive powers. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:266–272. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Rosenberg NA. Use of unlinked genetic markers to detect population stratification in association studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1999;65(1):220–8. doi: 10.1086/302449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulsinger F, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, et al. A family study of suicide. In: Schou M, Stromgren E, editors. Origin, prevention and treatment of affective disorders. London: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Semplicini A, Lenzini L, Sartori M, et al. Reduced expression of regulator of G-protein signaling 2 (RGS2) in hypertensive patients increases calcium mobilization and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by angiotensin II. Journal of Hypertension. 2006;24(6):1115–24. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226202.80689.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS Social Support Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoller JW, Paulus MP, Fagerness JA, et al. RGS2 influences anxiety-related temperament, personality and brain function. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65(3):298–308. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statham DJ, Heath AC, Madden PAF, et al. Suicidal behaviour: An epidemiological and genetic study. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:839–855. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Schork NJ, Gelernter J. A polymorphism of the beta1-adrenergic receptor is associated with low extraversion. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56(4):217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender PH, Kety SS, Rosenthal D, et al. Psychiatric disorders in the biological and adoptive families of adopted individuals with affective disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:923–929. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800100013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2003: Shaping the future. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang BZ, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, et al. Characterization of a Likelihood Based Method and Effects of Markers Informativeness in Evaluation of Admixture and Population Group Assignment. BMC Genet. 2005;6(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang BZ, Zhao H, Kranzler HR, et al. Practical population group assignment with selected informative markers: Characteristics and properties of Bayesian clustering via STRUCTURE. Genetic Epidemiology. 2005;28:302–12. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]