Abstract

A realistic representation of water molecules is important in molecular dynamics simulation of proteins. However, the standard method of solvating biomolecules, i.e. immersing them in a box of water with periodic boundary conditions, is computationally expensive. The primary hydration shell (PHS) method, developed more than a decade ago and implemented in CHARMM, uses only a thin shell of water around the system of interest, and so greatly reduces the computational cost of simulations. Applying the PHS method, especially to larger proteins, revealed that further optimization and a partial reworking was required and here we present several improvements to its performance. The model is applied to systems with different sizes, and both water and protein behaviors are compared with those observed in standard simulations with periodic boundary conditions and, in some cases, with experimental data. The advantages of the modified PHS method over its original implementation are clearly apparent when it is applied to simulating the 82 KD protein Malate Synthase G.

Keywords: Molecular Dynamics Simulation, Primary Hydration Shell, Protein Dynamics, Water, Solvent Representation

Introduction

In the past few decades, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become increasingly accurate (and popular) thanks to the ever-increasing computational power, and more precise potential functions as well as sophisticated simulation programs such as CHARMM1, Amber2, and NAMD3. Due to the computational cost it is necessary to limit the size of the system in MD simulations by application of appropriate boundary conditions. In simulations of proteins, the most commonly used approach is to immerse the macromolecule in a box full of explicitly represented water molecules with periodic boundary conditions (PBC). The presence of the water molecules is of great importance, as water plays a crucial role in protein structure, stability and function. Despite advances in the speed of computers and the efficiency of algorithms, simulations of large biomolecules are still a computational challenge as the majority (up to 90%) of the simulation time is typically spent on the calculations involving water molecules alone.

The high computational cost of PBC has motivated researchers to seek other approaches to account for the effect of water-protein interactions. These alternative methods include implicit solvent models4–6, hybrid explicit/implicit methods7,8, and models that use only a thin sell of water around the protein9–12. Implicit and hybrid solvent models have their own challenges. At least in our hands several implicit models did not perform as well as anticipated, both in terms of CPU time and accuracy13. Instead we have focused our attention on models utilizing only a thin layer of water molecules around the protein. Such approaches have been proposed by different authors; Steinbach and Brooks8 used an unconstrained shell of waters to simulate the protein myoglobin and showed that this maintained accurate protein behavior. However, in such simulations, typically a large number of waters evaporate into vacuum over time (10–100ns). In order to overcome this problem, Sankararamkrishnan et al, for example, used two spherical shells of water to solvate a protein and constrained the outer shell to remain around the first one with a radially symmetric harmonic force10. Li and co-workers, on the other hand, used a fluctuating elastic bag (a network of quasi-particles connected by elastic nonds) to keep the solvent molecules around the solute11. An advanced model of this type of solvation is the so-called “primary hydration shell” (PHS) method, developed by Beglov and Roux12. In this approach the protein of interest is solvated using a thin shell of water but the waters are brought back by a restraining force if they are more than a certain distance from the nearest protein atom. It is important to note that this method results in a water shell whose shape follows that of the protein and thus the approach can in principal be used for protein (un-)folding simulations as well as for calculations in which the protein undergoes considerable conformational changes.

We have recently shown that the PHS method indeed leads to acceptable water and especially protein behavior13, and so deserves more attention. In our previous paper we reported that the PHS method, when used to simulate the modest sized protein hen lysozyme, leads to results very similar to those obtained by using a full box of water and PBC. Primary hydration shell method was shown to be about one order of magnitude faster than the simulation with PBC. The advantage of using the PHS model is expected to become more obvious in simulating larger biological systems, as the number of water molecules are needed to fully solvate the protein under periodic boundary conditions is increased. When we applied the PHS method to a larger system, however, we found several issues that required optimization and are reported in this paper. For example, we implemented a neighbor-list to efficiently find the closest protein atom to the oxygen atom of water molecules, leading to greater computational performance for larger systems. Furthermore, we implemented a way to control the pressure of the system and scaled the potential so that waters remain near hydrophobic surface residues. Using the modified version of the PHS method good agreement with a PBC simulation can be obtained for a 82 kDa protein with a saving of computing time that is greater than 14-fold.

The modified PHS method

In the original PHS (OPHS) method as implemented in CHARMM, in each simulation step, the distance d between the oxygen atom of each water molecule and the nearest heavy protein atom is calculated and compared to the sum of the shell thickness R, and the Van der Waals radius a of the protein atom. To avoid evaporation of the water molecules, if d > R + a , a force of the magnitude K1 (d−(R+a)) is applied to the oxygen atom of the water molecule in the direction of the closest protein atom in order to retain the water inside the shell. Here K1 is a constant with a default value of 3.0 kcal/(Mol Å2). To prevent net translation and rotation of the entire system, an equal force is exerted on the nearest protein atom in the opposite direction12. In order to find the closest protein atom to each water molecule, in each simulation step, all distances between the oxygen atoms of waters and the heavy atoms of the protein are calculated. This procedure becomes computationally expensive for large systems. For example, according to our estimate, in an OPHS simulation of hen lysozyme (with 1960 protein atoms and 750 water molecules) about 35% of the CPU time was used for PHS-related calculations (mostly spent on determining the distances), whereas in the simulation of the protein Malate Synthase G (with 11283 protein atoms and 6645 water molecules) the CPU usage for this task was approximately 85%. To avoid this problem a nearest neighbor list was introduced into the PHS code as follows: at the beginning of a dynamics run, all inter-atomic distances between all atom pairs are calculated and the nearest protein atom to each water molecule is determined. Then the water molecules whose distances to the nearest protein atoms, d , satisfy the relation on d > a + (1 − r1)R are identified and stored in a list (the “water list”). Here r1 is a user-defined parameter that can be any number between unity and zero, which in this study was chosen to be 0.25. The listed waters are the ones that are close to the solvent-vacuum boundary, and so may evaporate. For each chosen water molecule, a neighbor list is then determined, containing the protein heavy atoms whose distance from the water is smaller than r2R, where r2 is another parameter defined by the user (should be set to a value bigger than one, in this study set to 2.5). In the following steps of the simulation, the pair-wise distances are only calculated between the solvent molecules in the water list and their neighbors. In this way the number of distance calculations is reduced several-fold (more than 20-fold in the case of Malate Synthase G). However, the water molecules near the shell boundary tend to move quickly, and so the water list and the neighboring lists are updated every N (10 in this study) steps.

The PHS model dramatically lowers the computational cost of protein simulations compared to the ones that employ full boxes of water and periodic boundary conditions, but the method lacks several features of the simulations with PBC. One important issue is the fact that the pressure of the entire system is not easy to control in the original PHS model. In the original implementation Beglov and Roux12 suggested a way to keep the density of the water molecules constant. This is accomplished by allowing the thickness of the shell to vary according to the relation:

| (1) |

where C is a relaxation constant, F0 is a reference value, and is the averaged harmonic force over all water molecules. The reference force was set to F0 = 0.9 kcal/(Mol Å) based on simulations involving water spheres. Although this approach typically results in an appropriate water density, the pressure on the system can be very high. In fact the average pressure in a 10 ns simulation of a water sphere of radius 20 Å using the original PHS method was about 400 Atm (see the results section). In the original implementation of the PHS method in CHARMM, the default value for the relaxation coefficient C is zero resulting in shells with constant thickness, but in all simulations run using OPHS for this paper, C was chosen to be 0.25 Å2/(ps kcal/Mol). Other parameters were set to the default values, i.e. K1=3 kcal/(Mol Å2), and F0 = 0.9 kcal/(Mol Å).

In the modified version of the PHS method (MPHS) a different approach is used to maintain the right water density. Following Lounnas et al7 we assume that the volume occupied by the water molecules Vw is equal to Nw Vm, where Nw is the number of waters and Vm ≈ 29.9 Å3 is the average volume per molecule under the ambient conditions. However, in the PHS method the solvent molecules are free to move in the water shell, and so the volume of the shell, denoted by Vs, should be always kept close to Nw Vm. The thickness of the shell R, therefore, is adjusted as

| (2) |

to make sure that Vs − Nw Vw remains small during the simulation. Here C1 is a user-defined constant chosen to be 10−5 1/Å2 in all MPHS simulations reported here. Since volume determination is computationally expensive, this calculation and the adjustment of the thickness of the shell are performed every 1000 steps. To be able to use Eq. (2), however, one needs to first determine Vs. Fortunately, an algorithm for calculation of the volume of a set of atoms has already been implemented in CHARMM (the VOLUME command). The algorithm searches, by using a grid, for points that are outside the Van der Waals radii of the atoms, and so calculates the volume of the empty and filled points. In the modified PHS method the volume of the protein Vp is calculated using this grid-based method. Since the “shell” around the protein is defined as all points in space whose distance to the nearest protein atom is less than R + a, it is reasonable to define the total volume of the system V as the volume of the protein, when the Van der Waals radii of the atoms (a) are replaced by R+a. The volume of the shell, Vs, can then be written as V − Vp.

In this study, the PHS method has also been modified to allow pressure control. To the best of our knowledge only Lounnas et al have attempted to control the pressure in an MD simulation of a protein surrounded by a shell of water7. However, the pressure in their method was calculated only for the solvent, and not for the protein. Generally, in MD simulations of non-periodic systems the pressure is not calculated, because the volume of such a system is not well-defined. However, once the volume is calculated, as described in the previous paragraph, the instantaneous external (Pext) and internal (Pint) pressures can be determined. Pint, for example, can be written as14:

| (3) |

with and K being the internal Virial, and the kinetic energy of the system. Here is the position of the ith particle, and is the total internal force acting on it. In the MPHS method the total volume of the system is passed to the CHARMM subroutines that calculate the pressure, and so both internal and external pressures are computed for the whole system. It should be noted that the thermodynamic pressure is the average of the instantaneous values over a long period of time, and that in equilibrium Pext and Pint are expected to be equal. A similar approach can be used to calculate the pressure in OPHS simulations. As mentioned before, the results of such calculations indicated that the system experienced a large pressure when simulated using OPHS. The large pressure can be attributed to the half-harmonic force that is applied to prevent evaporation of the water molecules. Therefore, in the modified version an additional half-harmonic potential is added to the energy function of the system exerting a counter force on the members of the water list (described above) that are inside the water shell, i.e. the water molecules in the list for which d < R+a. The magnitude of the force is K2((R+a)−d), where K2 is the force constant and is usually much smaller than K1. The force is applied along a vector connecting the oxygen of the water molecule and the nearest protein heavy atom, and is pointed outwards (towards the vacuum). In other words, the two half-harmonic forces form an asymmetric potential well whose center is at the border of the shell. To keep the pressure constant at the desired value the quantity s = K2 / K1 is varied in every simulation step as follows:

| (4) |

where C2 is a constant, Pext (t) is the instantaneous external pressure and Pref is the desired pressure. In simulations with the modified PHS model discussed in the following sections, C2 was set to 0.005 1/(Atm ps). This value for C2 was chosen after running several test simulations. The parameter has to be small, because the fluctuations in the instantaneous pressure are very large, and so larger C2 values would result in unstable simulations.

We also noticed that in simulations using the original PHS method some of the hydrophobic residues of the protein are partially desolvated, which is due the redistribution of the water molecules around the protein. One reason for this was the problem with pressure and local density of waters and the introduction of a modest force towards the boundary (akin to the SBOUND potential15 in CHARMM) alleviated this trend. In addition different force constants were used for the “inward” half-harmonic force acting on the waters, depending on the hydrophobicity of the nearest protein residue. In the modified version of the method, if the nearest protein atom to a given water molecule belongs to a polar residue, the force constant (K1) is lower (5 kcal/Mol Å2) than the case that the nearest residue is non-polar (15 kcal/Mol Å2). In this way water can not buldge out (beyond the shell cut-off) around hydrophilic regions and water is forced back to hydrophobic regions. Both values were chosen empirically based on several test simulations (see results below).

To calibrate and validate the modified version of the PHS model, several MD simulations were performed for systems with different protein sizes. Most of the simulations were also run using the original PHS and PBC (full water box) methods to compare the results. All PHS simulations were run using the original or a PHS-modified version of CHARMM (c35a2), in conjunction with the CHARMM22/CMAP force field, and the TIP3 water model. Some of the full-box simulations were run using the more efficient program NAMD using the same force field and water model. The modified PHS (MPHS) model was first used to investigate the effect of the outward half-harmonic force on the water distribution in the simplest system possible i.e. a water sphere. A fixed dummy atom at the center of the sphere played the role of the protein. The model was then applied to simulate the Rho binding domain (RBD) of the transmembrane receptor Plexin B1. This is a relatively small protein (122 residues) whose structure has been solved in our laboratory16. In all PHS simulations of the RBD the unstructured C- and N-terminal of the protein were truncated, leaving only residues 5–112. To evaluate the efficiency of the new model for larger systems, simulations of the protein Malate Synthase G (PDB code 2jqx) were also run17. This 723 residue protein will be referred to as MSG in the rest of the paper.

In each simulation the protein of interest (or the dummy atom in the water-sphere simulations) was first placed in a box of explicit water. All solvent molecules with distances less than 2.8 Å from any protein atom were deleted, eliminating solvent – protein overlap. In the PHS simulations of the water-sphere, the RBD, and MSG proteins, water molecules were also deleted that were, respectively, further than 20, 9.5, and 11 Å from the nearest protein atom (or the dummy atom in the water-sphere simulations). The simulations were performed at the constant temperature of 300 K by use of the Berendsen thermostat18. In the full-box simulations the pressure was also kept constant at 1 Atm using the Langevin piston method14. The average length of each side of the solvent box was about 69, and 98 Å in PBC simulations of plexin RBD, and MSG respectively. The cutoff for the nonbonded interactions in the PHS simulations was set to 13 A, and was switched off over a 4 Å interval. In simulations with periodic boundary conditions the cutoff was 12 Å, and the long-range electrostatic forces were calculated using the PME (Particle-Mesh Ewald) method. Counter ions were added to the systems with PBC to neutralize the system. A time step of 2 fs was used, and the bonds between hydrogens and other atoms were kept rigid using the SHAKE algorithm19. In each case the system was prepared as follows: in the first step of all PHS simulations, the protein was fixed, while the remainder of the system was minimized and heated up to 300 °K. The restraint on the protein was then lifted (the dummy atom in the case of water sphere was always fixed) and another round of minimization was run. A short simulation was carried out to heat up and equilibrate the system. During the initial minimization and heating in the PHS simulations the thickness of the shell was held fixed at 20, 7, and 7 Å for the water sphere, plexin RBD, and MSG respectively. Also, when the modified version was used, the outward force was only applied after the system had been minimized and heated up. The preparation stage for the PBC simulations was slightly different, as the number of atoms was much larger. In these simulations, after the initial minimization a short NVT simulation was run at 50 °K. The protein was then released and a similar simulation was run at 50 °K. The system subsequently was heated up to 300 °K and then was equilibrated by running short simulations.

Results and discussion

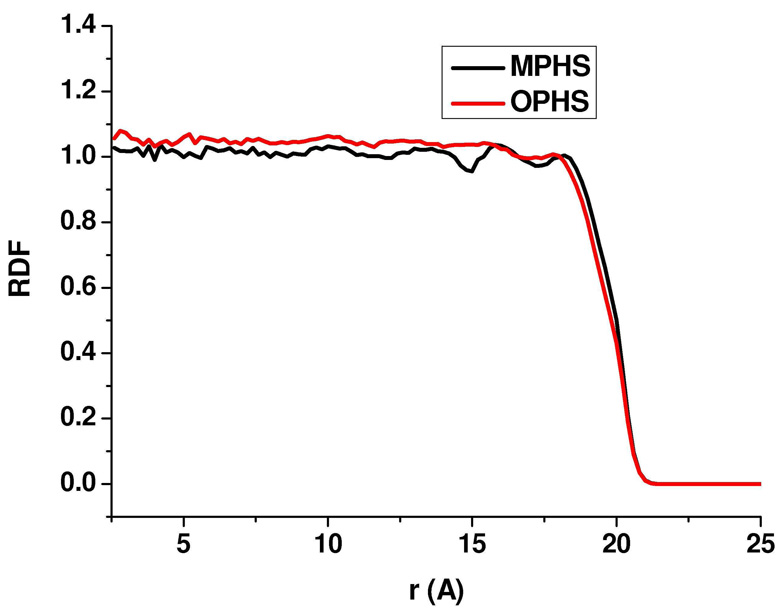

Several molecular dynamics simulations were run to test the modifications to the PHS method and to compare the results with those from the original method or from PBC simulations. One of the most important aspects in our refinement of the PHS method was the introduction of the additional “outward” force. The modified potential is expected to change the distribution of water around the protein, and to increase the water density at the solvent boundary. To show that the change in water distribution is minimal, the new and original PHS models were used to simulate a water sphere of radius 20 Å containing 1108 water molecules, as described above. The average shell radius remained very close to 20 Å in both simulations (about 19.9 Å). The calculated external pressure, averaged over the whole trajectory, in the simulation using the original model was more than 400 atm, as opposed to 1.004 atm in the simulation with the modified method. The ratio s = K2 / K1 of the constants of the “outward” and “inward” forces was found to be 0.01, when averaged over the entire trajectory. The radial distribution functions (RDFs) for the oxygen atoms of the water molecules around the dummy atom at the center of the sphere are shown in Fig. 1. The figure suggests that adding the additional outward force does not significantly change the water distribution. It is however clear that the radial density of water in the simulation with the revised model is generally less than that of the simulation with the original PHS for 0 ≤ r ≤ 18 Å and more for r > 18 Å. The small difference between the RDFs is expected, as the additional force is small. Interestingly, in this case of a water sphere, application of this small force and adjusting s = K2 / K1 reduce the pressure by a factor 400.

Figure 1.

Radial distribution functions (RDFs) for the oxygen atoms of the water molecules, calculated from the position of a dummy atom at the center of the water sphere for simulations performed using the modified and original PHS methods. The plot shows a higher water density at the solvent boundary when the modified method is used.

The second system studied here, the Plexin RBD was simulated for 30 ns using both the original and modified versions of the PHS model, and also using a full box of water and PBC. For each method a total of four simulations were run with different random starting seeds in order to obtain better statistics. Simulations with PBC were carried out using NAMD, which provides better scalability than CHARMM. Table I summarizes results averaged over the last 10 ns of the simulations. As shown the average thickness of the water-shell is about 7.5 Å in all PHS simulations, and no significant difference was observed in this parameter between the modified and original method. Similar to the case of the water sphere, discussed above, the ratio of the outward and inward force constants applied in the MPHS (modified PHS) simulations is small, suggesting a slight change in radial distribution of the water molecules. The table also indicates that the average main-chain RMSDs, the departure from the starting coordinate position for the plexin RBD (residues 5–112), are very similar in all the MPHS and PBC, and three OPHS (original PHS) simulations. One of the OPHS simulations, however, resulted in a noticeably higher RMSD (6.2 Å). This may be due to the high pressure experienced by the protein in the OPHS simulation, which tends to unfold it. The average pressure in all PBC and MPHS runs remained very close to 1 Atm. In order to investigate how different methods preserve the secondary structure of the protein, the total number of protein-protein hydrogen bonds was also calculated using a distance cut-off of 2.4 Å for the C=O…H-N bonds (Table I). It is interesting to note that the numbers of hydrogen bonds obtained from the MPHS and PBC trajectories are very similar, whereas the OPHS simulations resulted in significantly smaller number of hydrogen bonds. This clearly demonstrates the advantage of MPHS over OPHS in preserving the secondary structure of the protein.

Table I.

The water shell thicknesses, ratios of the force constants, RMSDs, and total number of protein hydrogen bonds, averaged over the last 10 ns of the trajectories, are given for the plexin RBD.

| Method used | Thickness of the water shell (Å) | S = K2 / K1 | RMSD (Å) | Number of protein hydrogen bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC | N/A | N/A | 4.0 | 179 |

| 4.5 | 173 | |||

| 4.0 | 167 | |||

| 4.9 | 171 | |||

| Modified PHS | 7.5 | 0.057 | 4.5 | 177 |

| 7.5 | 0.053 | 4.4 | 165 | |

| 7.6 | 0.063 | 4.2 | 183 | |

| 7.3 | 0.063 | 4.9 | 178 | |

| Original PHS | 7.3 | N/A | 6.2 | 133 |

| 7.4 | 4.4 | 139 | ||

| 7.4 | 4.1 | 142 | ||

| 7.6 | 4.2 | 140 | ||

It is also important to examine the water dynamics around the protein when the different simulation methods are used. The first (P1) and second (P2) rank rotational correlation functions, and the Mean Square Displacements (MSDs), were calculated for the solvent molecules in the first and second water-shells (defined below). We also calculated the ratio n(t) = N(t)/N(0), i.e. the fraction of the water molecules that remain in a certain shell after time t. This quantity can be used to calculate the life time of a water molecule in each shell. The water molecules within 4 Å from the protein were considered to be in the first shell, whereas the second shell was defined as the solvent molecules that reside within 7 Å from the protein and do not belong to the first shell. Since the water molecules can move rapidly from one shell to another, it is necessary to consider only the molecules that remain in a certain shell for the duration of calculations (20 ps and 5 ps for the first and second shell respectively). For this reason a 100 ps simulation was run, starting from the final structure of each 30 ns trajectory, where the coordinates were saved every step. All calculated quantities were averaged over the solvent molecules, 20 time origins, and the four simulations. The results are summarized in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 for the first and second shell. Figures 2a and 2b demonstrate that in the MPHS and OPHS simulations, the rotational dynamics of waters is slower and faster, respectively, than in the PBC simulations. However, both PHS methods result in acceptable rotational behavior (close to that of the PBC). As indicated in Fig 2c, the diffusion of the solvent molecules predicted by both PHS simulations (especially MPHS) is slower than that in simulations using a full box of water. Still, the difference in the diffusion coefficients is not large (less than 30%). Finally, Fig. 2d shows no significant difference between the residency behaviors of water molecules in the first shell when different solvation methods are used. Importantly, rotational and translational diffusion of the solvent molecules in the second shell are almost identical (Fig 3a, 3b, and 3c). Figure 3d, however, suggests that the waters simulated using MPHS, tend to stay longer in the second shell by comparison to the other simulations. This is perhaps due to the additional outward force that tends to keep the waters close to the solvent boundary. Overall, the solvent dynamics is similar in all simulations, suggesting that both PHS methods lead to acceptable water behavior around the plexin RBD.

Figure 2.

Water dynamics in the first shell around Plexin RBD. (a) First rank rotational correlation function, (b) second rank rotational correlation function, (c) mean square displacement, and (d) fraction of water molecules that remain in the shell after time t.

Figure 3.

Water dynamics in the second shell around Plexin RBD. (a) First rank rotational correlation function, (b) second rank rotational correlation function, (c) mean square displacement, and (d) fraction of water molecules that remain in the shell after time t.

As mentioned above, one of the issues with the original PHS method is the partial desolvation of some parts of the protein surface, especially close to non-polar residues over long simulation times. Visual inspection revealed a considerable difference between the distribution of solvent molecules around the RBD in OPHS and MPHS simulations, indicating a much more uniform distribution when MPHS was used. To quantitatively demonstrate how MPHS improves solvation of the protein, the number of water molecules around a surface cluster of hydrophobic residues V86, Q87, G88, L89, and F90 in the plexin RBD protein was calculated for different simulations. From each 30 ns trajectory, 300 frames were chosen and for each frame the water molecules whose oxygen atoms were within 8 Å of the geometrical center of the side-chain heavy atoms (including Cα atoms) of any of these residues, were counted. The numbers were then averaged over all frames and over the four simulations. The average numbers of solvent molecules around this hydrophobic region were 73, 103, and 113 for the OPHS, MPHS, and PBC simulations respectively. To see this pictorially, the region of the protein is shown in Fig. 4 (prepared using Pymol20). The figure shows the last frame at 30 ns for each of the four MPHS (right panel) and OPHS (left panel) simulations. The partial desolvation of the protein in OPHS simulations is especially obvious in the third OPHS simulation (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

The solvation of hydrophobic region res. 86–90 of the plexin RBD, discussed in the text, is shown. The figure shows the last frame of the 4 OPHS (a, b, c, and d), and MPHS (e, f, g, and h).

The computational advantages of using MPHS become more obvious when the goal is to simulate a large system. Most importantly, the decrease in computational cost of MD simulations with MPHS in comparison to other methods is expected to be more significant for larger systems. Also, it appears that, when OPHS is used, the risk of protein distortion and unfolding due to large pressure significant for larger systems. To show how MPHS improves the simulations of large proteins, the 723 residue protein MSG was simulated using both OPHS and MPHS methods. Four MPHS simulations were run for 30 ns, but only one OPHS simulation was run, due to the higher cost of computational resources by this method. This simulation was discontinued after 10 ns, as it became apparent that the protein was distorted (see below), and the simulation was not stable. Again, due to limitation in computing resources only a 10 ns simulation was run using the standard PBC method. Table II summarizes the number of atoms, and the simulation times for all simulations run for plexin RBD and MSG. The PBC simulations for the plexin RBD and MSG were run using 32 and 64 processors respectively. However, to be able to compare the simulation times with those of the PHS runs, two short simulations were performed using 8 and 16 processors for the RBD and MSG respectively. The simulation times were then estimated based on these short simulations. It is clear from the table that MPHS is much more efficient for larger systems, and that the OPHS is almost four times slower, when it is used to simulate the MSG protein.

Table II.

Number of atoms and simulation times for the RBD and MSG proteins using different methods. In the RBD and MSG simulations 8 and 16 processors were used respectively.

| System | Method | Number of atoms | Simulation time (hours/ns) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBD | MPHS | 7040 | 4 |

| OPHS | 7040 | 6 | |

| PBC | 33167 | 65 | |

| MSG | MPHS | 31218 | 23 |

| OPHS | 31218 | 85 | |

| PBC | 96439 | 320 | |

We also analyzed the water behavior around the MSG protein using the same approach as for the RBD simulations above. The results (data not shown) were very similar to the RBD case, indicating closely identical water behavior in the three computational methods.

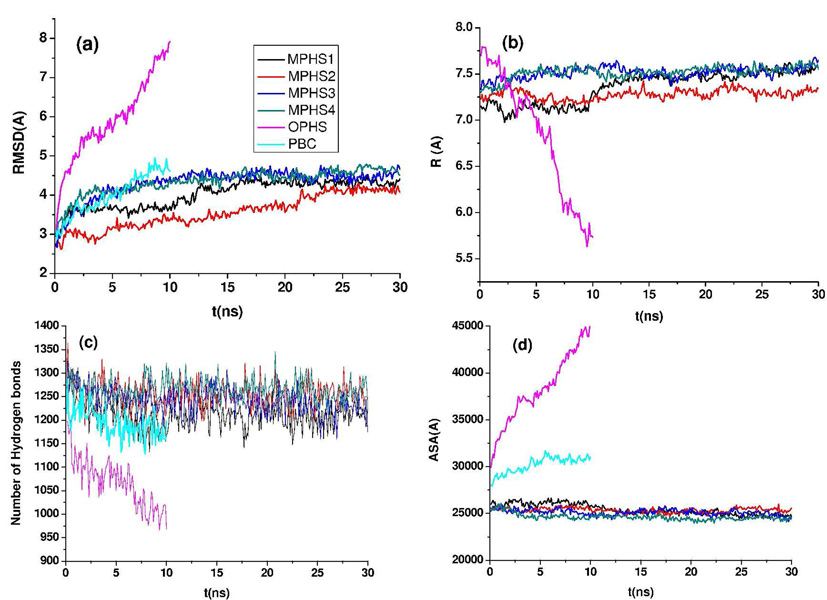

Unlike the solvent behavior, the MSG protein dynamics was found to be very different when the two PHS methods were used. Several quantities were calculated to investigate the dynamics of MSG simulated with the different solvation methods. Figure 5a shows the back-bone RMSD of the protein derived from the four MPHS, the OPHS, and the PBC simulations. The RMSD from the OPHS simulation is much higher, and also does not appear to be equilibrated after 10 ns. The 4 MPHS simulations remained stable in the entire simulation (30 ns), although in two cases the system takes a long time to equilibrate. In the PBC case, the protein equilibrates after 7–8 ns with an RMSD of about 4.5 Å, which is very close to the RMSD calculated from the MPHS trajectories. The fact that the OPHS simulation is not equilibrated is also obvious from Figure 5b where the thickness of the shell R has been plotted as a function of time for the MPHS and the OPHS simulations. The sharp decrease in R, when the OPHS method is used, indicates that the pressure on the protein is very large and that the water molecules are penetrating inside the protein, which explains large RMSD from the initial structure. The total number of protein-protein hydrogen bonds were also calculated and are shown in Fig. 5c, which confirms that the protein loses hydrogen bonds when simulated by OPHS, whereas the PBC and MPHS methods give very similar results in the first 10 ns. Also shown in Fig. 5 is the accessible surface area (ASA) of the protein as a function of time. In the MPHS simulations, ASA equilibrates at a value very close to the initial after a slight decrease (Fig. 5d). In the OPHS simulation, however, ASA increases sharply, which indicates that the protein has been partially unfolded due to the high pressure. The ASA obtained from the PBC simulation is equilibrated at a value slightly larger than the initial accessible surface area, but this value is not very far from the MPHS result.

Figure 5.

(a) RMSD from the starting structure. (b) Thickness of the shell. (c) Total number of protein-protein hydrogen bonds. (d) Accessible surface area.

The dynamics of the protein can also be investigated by calculating the RMS fluctuations (RMSF) of each residue during the simulation. For each MSG simulation the RMSF was calculated as a function of residue over the first 10 ns of the trajectory. One can compare these results with the fluctuations inferred from the experimental B-factors, B, of a crystal structure (PDB code 1D8C) using the relation on RMSF = (3B/8π2)1/2. The average correlation coefficient between the RMSF values derived from MPHS simulations and those calculated from the B-factors was found to be 0.46, which was comparable to the corresponding correlation coefficients for OPHS and PBC simulations (0.44 and 0.42 respectively). However, in accordance with our previous results, the RMSF of most residues calculated from OPHS trajectories were found to be considerably larger than those derived from MPHS simulations. In fact the average RMS difference between the MPHS results and experimental values was 0.4 Å as opposed to 0.9 Å for PBC and 1.4 Å for OPHS simulations.

Based on the results given in this paper, the MPHS method is capable of accurately simulating relatively large systems like MSG. However, it needs more testing for a wider range of applications and is likely to be limited for several. Specifically, the current version of the model does not include possible effects of long-range electrostatic interactions, which may become an important limiting factor in applying the model for highly charged systems, such as nucleic acids or when long range protein-protein interactions are critical, for example in the refinement of the output structures of a docking calculation, involving two or more proteins. In the case of proteins or protein-regions coming together over longer distances in the simulation, another aspect of the primary hydration shell model is likely to cause problems: As found in our previous report13, using only a shell of water around the protein results in a small population of waters with preferred orientation at the solvent-vacuum boundary, which could create artifacts when the two solvent shells come together. Another limitation of the model is that it cannot be used for studying the (translational or rotational) diffusion of the protein of interest, since in the PHS method (original or modified) the protein does not, on average, move or rotate relative to the solvent.

The MPHS method could, in principle, be applied for the study of peptide or larger protein extensive conformational transitions. While the MPHS method would not offer a large time-saving in case of a peptide, the method should be suitable for protein conformational transitions since the water shell is not required to be spherical and follows the shape of the polypeptide. However, in the current implementation the number of waters are constant in the simulation and if there is a considerable increase in surface area, e.g. in the case of unfolding, one might want to start the simulation of the folded protein with a larger shell of water than used here. In principle it should also be possible to combine the MPHS method with accelerated dynamics or replica exchange methods designed to enhance conformational sampling.

We have also not tested the MPHS with free energy calculations, and one should be cautious as such simulations are usually carried out by employing the thermodynamic integration method (e.g. see Ref.21) which involves transformation of the potential energy function of the system. If such a transformation (e.g. a mutation) results in a change in the net charge of the system, then long-range electrostatic interactions make a major contribution to the free energy and the modified PHS method is likely to produce inaccurate results. Given the concerns discussed above, we do not recommend the use of the modified PHS method at this point for non-protein applications or methods that go beyond conformational sampling.

In the future we will apply and test the MPHS method to still larger systems. Furthermore, we are interested in developing the primary hydration shell model further so that it can be used to study the interaction between lipid bilayers and trans-membrane receptors.

Summary

In this paper, we present modifications to the primary hydration shell method for protein dynamics simulations. The method was developed to save computing time by using only 2–3 layers of water molecules around the protein as solvent. Compared to the standard method using periodic boundary conditions and an explicit solvent filled box, PHS methods speed up simulations by several fold. The ratio between the numbers of water molecules in the PBC and PHS simulations of the MSG protein was about 4, whereas this ratio and the corresponding speed-up can be much higher for the simulation of irregularly shaped molecules. In the modified version of the PHS method, presented in this report, we achieved improved computational efficiency due to the introduction of a water near neighbor list, which is especially valuable for larger systems.

It was demonstrated that the large pressure exerted on the protein in simulations with the original PHS method can result in unstable behavior and partial unfolding, especially when the system is large. We implemented a method to control the pressure and produced results that are in good agreement with those derived from standard simulations. Also, the partial desolvation of hydrophobic residues was prevented by a scaling of the water retention force in the modified version of the method. Overall, MPHS appears to be a robust method for fast and reliable simulations of large proteins.

Acknowledgement

MBH is supported by a fellowship from the American Heart Association, award number 0725527B. MB acknowledges the support of the National Institute of Health grant GM73071

References

- 1.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Case DA, Cheatham T, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods R. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1668. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Philips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Im W, Lee MS, Brooks CL. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1691. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazaridis T, Karplus M. Proteins: Struct., Funct., and Gen. 1999;35:133. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990501)35:2<133::aid-prot1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Im W, Berneche S, Roux B. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:2924. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lounnas V, Ludemann SK, Wade RC. Biophys Chem. 1999;78:157. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(98)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee MS, Olson MA. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:5223. doi: 10.1021/jp046377z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbach PJ, Brooks BR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sankararamakrishnan R, Konvicka K, Mehler EL, Weinstein H. Internatioinal Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 2000;77:174. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Krilov G, Berne BJ. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:463. doi: 10.1021/jp046852t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beglov D, Roux B. Biopolymers. 1994;35:171. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaneh MB, Buck M. Biophys J. 2007;92:L49. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.103010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:4613. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks CL, Karplus M. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:6312. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong Y, Chugha P, Hota PK, Li M, Alviani RS, Tempel W, Shen L, Park HW, Buck M. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703800200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grishaev A, Tugarinov V, Kay LE, Trewhella J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2008;40:95. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Van Gunsteren WF, Dinola A, Haak JR. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryckaert J, Ciccotti P, Berendsen G. J Comp Phys. 1977;23:327. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; DeLano Scientific. CA, USA: Palo Alto; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker OM, MacKerell AD, Roux B, Watanabe M. Computational Biochemistry and Biophysics. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 2001. Chapter 9. [Google Scholar]