Abstract

Spontaneous renal hemorrhage (SRH) is a difficult diagnostic problem with various causes. We report a case of SRH and episodic gross hematuria in a patient with metastatic choriocarcinoma involving both kidneys for which successful angioembolization was carried out for control of hemorrhage. There was no evidence of primary uterine tumor and pulmonary or liver involvement. The patient developed gastrointestinal bleeding due to jejunal metastasis while on chemotherapy and surgical resection of the involved segment was carried. However, the patient acquired nosocomial pneumonia and succumbed to sepsis in the postoperative period.

Keywords: Choriocarcinoma, metastasis, renal, jejunum, computed tomography, angioembolization

Introduction

Spontaneous renal hemorrhage (SRH) is a difficult diagnostic and management problem. The differential diagnosis of SRH includes a myriad of causes, ranging from malignant metastatic disease to the most benign urinary tract infection. Metastatic choriocarcinoma is a rare cause of SRH in females of child-bearing age. With the advent of highly effective chemotherapy, metastatic disease presentation has become rare. We report a case of SRH in a patient with metastatic choriocarcinoma presenting with gross hematuria that was successfully managed with angioembolization. The patient was started on chemotherapy, but she developed gastrointestinal bleeding due to jejunal metastasis that was managed with resection of the involved segment. The patient subsequently succumbed to sepsis in the postoperative period. The present case highlights the possible role of angioembolization for control of hemorrhage in such cases.

Case report

A 28-year-old women presented to us with right flank lump, hematuria and severe anemia (Hb 6.5%). She gave a past history of spontaneous abortion at 12 weeks gestation 2 years previously and subsequent normal vaginal delivery of an infant 4 months prior to the current presentation. A vaginal examination and ultrasound examination of the pelvis were normal. Renal functions and chest radiographs were normal. Ultrasound revealed a large perinephric hematoma on the right side. The computed tomography (CT) scan showed a large renal hematoma on the right side with a hypervascular renal mass showing multiple small aneurysms. A well-defined focal mass lesion in the interpolar region of the left kidney was also seen (Fig. 1). The uterus and the pelvic adnexa were normal. A diagnosis of bilateral renal angiomyolipomata with bleeding was under consideration but the renal masses did not show any gross fat densities on CT and the patient did not have any stigmata of tuberous sclerosis making this diagnosis improbable. Hence, a presumptive diagnosis of hypervascular renal metastasis from choriocarcinoma was considered, which was confirmed by significantly elevated serum β-HCG levels (705,000 IU/ml). A chemotherapy regimen comprising epirubicin, methotrexate, adriamycin, and oncovin (EMA-CO regime) was started; however, the patient continued to have episodic massive hematuria. A decision to undertake angioembolization of the renal masses was taken and angiography (DSA) was performed, which revealed a large hypervascular right renal mass with multiple small pseudoaneurysms and areas of contrast pudding within the renal mass (Fig. 2). Selective left renal angiogram also showed a focal hypervascular mass in the interpolar region with similar findings (Fig. 3). Selective embolization of bilateral renal lesions was performed using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles of size 300–500 µm (Cook, Bloomington, IN, USA) in the same sitting. After the procedure the patient had a mild fever and flank pain, which were controlled with antipyretics and analgesics. The serum creatinine level showed mild elevation (0.5 mg%), which settled to normal baseline level in 4 days. The hematuria subsided and the urine became clear while the patient continued on chemotherapy. On the 5th day after the procedure the patient developed abdominal distension and severe melena with a decrease in hemoglobin level from 9 to 3.9 g%. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was normal and an RBC scan for localization of intestinal bleeding showed pooling of tracer in small bowel loops. As the patient was becoming hemodynamically unstable as a result of ongoing intestinal bleeding, an urgent exploration was performed. An ulcero-polypoidal lesion of 2 × 2 cm causing intussusception was found in the mid jejunum (Fig. 4). Segmental resection and anastomosis of the jejunum was performed and histopathology of the resected bowel segment confirmed it to be choriocarcinoma metastasis to jejunum.

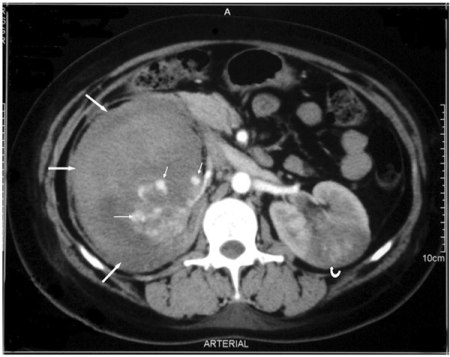

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT showing a large perirenal hematoma (arrows) compressing the right kidney with a hypervascular mass and microaneurysms (small arrows). A mass lesion is also noted in the left kidney (curved arrow).

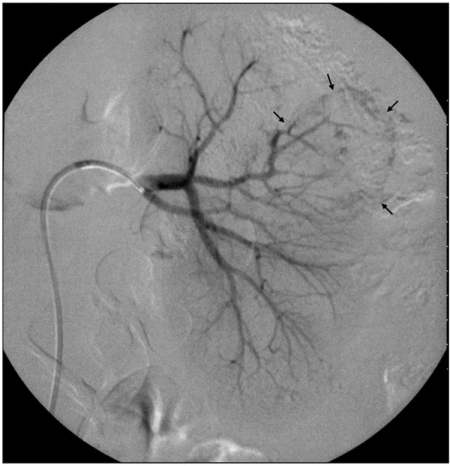

Figure 2.

Angiography of the right kidney showing multiple microaneurysms (arrows) and areas of contrast pudding.

Figure 3.

Angiography of the left kidney showing microaneurysms in the tumor-bearing segment (arrows).

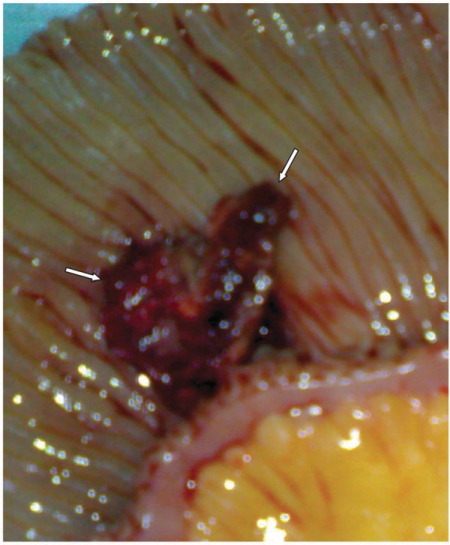

Figure 4.

The resected jejunal loop showing the ulcero-nodular growth due to metastatic choriocarcinoma (arrows).

The postoperative period was uneventful for the first 48 h and the bleeding stopped; however, the patient developed bronchopneumonia, which progressed to septicemia in spite of adequate broad spectrum antibiotics. As a result of ongoing sepsis, consumptive coagulopathy and pancytopenia unresponsive to GmCSF therapy, chemotherapy could not be continued. The patient was given ventilatory and ionotropic support in the critical care unit but succumbed to septicemia and multiorgan failure on the 7th postoperative day.

Discussion

SRH is often a difficult diagnostic problem because there are a wide variety of causes. The most common tumor causing SRH is renal cell carcinoma. The presence of bilateral renal lesions and SRH, angiomyolipomata or metastatic lesions to the kidney are all possible causes. With a past history of abortion and imaging findings not consistent with angiomyolipomata, metastatic choriocarcinoma was suspected in the index case, which was confirmed by grossly elevated serum β-HCG levels. In cases of SRH in women of child-bearing age, metastatic choriocarcinoma should be one of the differentials and evaluation of β-HCG is of paramount importance to confirm or refute the diagnosis in such cases[1].

Choriocarcinoma is the most malignant tumor of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. It grows rapidly and metastasizes to the lungs, liver, and, less frequently, the brain[2]. Renal and intestinal metastases are rare. The incidence of renal metastasis at autopsy varies from 1.8 to 11.8%, however in clinical practice it occurs in less than 5% of patients presenting for initial chemotherapy[3]. Primary presentation with hematuria and a renal mass is even rarer[4]. This malignancy is known to undergo spontaneous regression, and even in presence of metastasis, the primary lesion may not be apparent, as in our case. The index case had bilateral renal masses with large right renal hematoma. In view of the large hematoma and ongoing hematuria, angioembolization was performed using polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles; this procedure was successful as shown by cessation of hematuria. Angiography in cases of acute renal hemorrhage can detect abnormal bleeding vasculature or pseudoaneurysms and embolization can be performed for control of hemorrhage[4].

Metastatic renal choriocarcinoma has been described as an avascular lesion[5,6]. Considering the very vascular angiographic pattern of the primary lesion, this is an unexpected finding because most metastatic lesions have an angiographic appearance similar to the primary lesion[6]. It is thought that most choriocarcinoma metastases are initially vascular and, with growth of the tumor and extensive hemorrhage and necrosis, a variety of angiographic patterns evolve depending upon the stage of the lesion. The initial reports of metastatic choriocarcinoma to the kidney were most likely late in the evolution of metastasis and the bulk of the mass represented hemorrhage[7]. In our case, angiography was probably performed earlier in the development of the lesion and thus showed a profuse vascular pattern and microaneurysms.

The jejunal metastatic lesion was not picked up on the CT scan even on retrospective analysis of the images. This we attribute to the positive oral contrast that was used during the CT study to opacify the bowel lumen and obscuring the metastatic lesion. Symptomatic presentation with bilateral renal lesions and simultaneous jejunal metastasis of choriocarcinoma without chest and brain involvement is rare and we could not find any report of such a presentation in the English literature. The patient developed nosocomial pneumonia that led to sepsis and death in the postoperative period. Nevertheless, the present case highlights the role of angioembolization in cases of renal metastasis of choriocarcinoma for control of hemorrhage.

References

- 1.Chakrabarti J, Mishra PK, Mondal P, Ghosh D. Metastatic choriocarcinoma presenting as a renal mass. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2006;27:47–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li MC. Trophoblastic disease: natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1971;74:102–12. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-1-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thanikasalam K. Post hysterectomy choriocarcinoma with pulmonary and renal metastasis. Med J Malasia. 1991;46:187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vijay RKP, Kaduthodil MJ, Bottomley JR, Abdi S. Metastatic gestational trophoblastic tumour presenting as spontaneous subcapsular renal haematoma. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e234–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr/81495647. doi:10.1259/bjr/81495647. PMid:18769012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tai KS, Chan FL, Ngan HY. Renal metastasis from choriocarcinoma: MRI appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:536–8. doi: 10.1007/s002619900395. doi:10.1007/s002619900395. PMid:9841071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogunbiyi OA, Enweren EO, Ogunniyi JO. Unusual renal manifestations of choriocarcinoma. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1986;15:93–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soper JT, Mutch DG, Chin N, Clarke-Pearson DL, Hammond CB. Renal metastases of gestational trophoblastic disease: a report of eight cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:796–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]