Abstract

Background

Chemoresistance acquisition may influence cancer cell biology. Here, bioinformatics analysis of gene expression data was used to identify chemoresistance-associated changes in neuroblastoma biology.

Results

Bioinformatics analysis of gene expression data revealed that expression of angiogenesis-associated genes significantly differs between chemosensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. A subsequent systematic analysis of a panel of 14 chemosensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines in vitro and in animal experiments indicated a consistent shift to a more pro-angiogenic phenotype in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. The molecular mechanims underlying increased pro-angiogenic activity of neuroblastoma cells are individual and differ between the investigated chemoresistant cell lines. Treatment of animals carrying doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts with doxorubicin, a cytotoxic drug known to exert anti-angiogenic activity, resulted in decreased tumour vessel formation and growth indicating chemoresistance-associated enhanced pro-angiogenic activity to be relevant for tumour progression and to represent a potential therapeutic target.

Conclusion

A bioinformatics approach allowed to identify a relevant chemoresistance-associated shift in neuroblastoma cell biology. The chemoresistance-associated enhanced pro-angiogenic activity observed in neuroblastoma cells is relevant for tumour progression and represents a potential therapeutic target.

Background

Neuroblastoma is the most frequent extracranial solid tumour of childhood. About half of all neuroblastoma patients are diagnosed with high-risk disease with overall survival rates below 40% despite intensive multimodal treatment [1]. Therapy failure is basically caused by acquired chemoresistance. Primary tumours usually respond to initial chemotherapy. However, a significant fraction of tumours reappear as chemoresistant recidives [2].

Acquisition of chemoresistance under therapy may affect the biology of neuroblastoma and other tumour cells [3-9]. Mostly a shift towards a more malignant phenotype is observed indicating cancer progression [3,4,6-9]. Molecular changes in different signalling pathways including apoptosis signalling or cell cycle regulation may be involved in this coincidence of cancer cell chemoresistance and increased malignancy [3,10,11]. Neuroblastoma cells adapted to different cytotoxic drugs showed increased malignant properties as indicated by enhanced invasive potential in vitro [7,8] and increased malignancy in nude mice [9].

Here, differences in angiogenesis signalling were identified by bioinformatics pathway analysis of gene expression data from chemosensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Subsequently, cell culture and animal experiments using 14 human neuroblastoma cell lines indicated a consistently higher pro-angiogenic activity of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells than of chemosensitive cells. The molecular mechanisms underlying the chemoresistance-associated increased pro-angiogenic potential were individual and differed between individual cell lines. Doxorubicin treatment of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts resulted in impairment of tumour angiogenesis and growth suggesting the chemoresistance-associated pro-angiogenic phenotype to contribute to tumour progression.

Methods

Gene expression analysis

Gene expression analysis using AB1700 Human Genome Survey Microarray V2.0 chips (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) was performed by IMGM laboratories (Martinsried, Germany). Gene expression analysis using GeneChip HGU133 Plus 2.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was performed by Fraunhofer Institut für Zelltherapie und Immunologie (Leipzig, Germany). mRNA was isolated using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Triplicates of UKF-NB-3 RNA were compared to triplicates of UKF-NB-3rVCR10 RNA, UKF-NB-3rDOX20 RNA, or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 RNA.

AB1700 expression data were processed using the R/bioconductor package 'ABarray' (http://www.r-project.org/; http://www.bioconductor.org/) with default parameter (SN threshold > = 3, % Detect Samples: 0.5). This included quality control, quantile normalisation [12] and filtering of unspecific hybridisation. HGU133 Plus 2.0 expression data were processed using the R/bioconductor packages 'gcrma' and 'limma' (http://www.r-project.org/; http://www.bioconductor.org/).

For every microarray experiment, the expression pattern of 50 randomly chosen genes was verified by quantitative real-time PCR resulting in confirmation of expression of >80% of investigated genes (data not shown).

Signal transduction pathway bioinformatics

Statistical analysis to identify significant expression changes was focusing on a pathway analysis using the PANTHER database [13]http://www.pantherdb.org, which identifies global patterns in expression. For each expert-curated pathway in the database, potential differential expression was determined by a binomial test [14], using the PANTHER human gene reference list matching our microarrays (Human AB1700 genes) and lists of differentially expressed genes that passed a false discovery rate threshold [15] of 0.05 based on a t-test.

A total of 25,909 genes were annotated in the dataset, 3,125 of them included pathway information, and 223 of these (corresponding to 280 AB1700 ProbeIDs or 537 HGU133 Plus 2.0 ProbeIDs) were annotated as related to angiogenesis. For this list of angiogenesis-associated ProbeIDs and angiogenesis-associated genes signal intensities of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells were visualised as heatmaps using R http://www.r-project.org.

Cells

The cell lines UKF-NB-2, UKF-NB-3, and UKF-NB-4 were isolated from bone marrow metastases from N-myc-amplified stage 4 neuroblastoma patients [16-18]. Be(2)-C cells and IMR-32 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassass, VA, USA). Be(2)-C cells and UKF-NB-4 cells were isolated as chemoresistant cell lines from patients [17]. The parental UKF-NB-2, UKF-NB-3 or IMR-32 cells are chemosensitive (no P-gp expression, wild-type p53) [19]. Cells were adapted to growth in the presence of vincistine (10 ng/ml), doxorubicin (20 ng/ml), or cisplatin (1000 ng/ml) as described and named following the published nomenclature [16-20], e.g. UKF-NB-3rVCR10 means UKF-NB-3 adapted to vincristine 10 ng/ml, UKF-NB-3rDOX20 means UKF-NB-3 adapted to doxorubicin 20 ng/ml, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 means UKF-NB-3 adapted to cisplatin 1000 ng/ml. P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression and p53 status are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Influence of supernatants from different neuroblastoma cell lines on endothelial cell growth and endothelial cell survival

| P-gp1 | p53 mutation2 | Endothelial cell growth (%)3 | Endothelial cell survival (%)4 | |

| Positive control5 | 100 ± 8 | 100 ± 9 | ||

| Negative control6 | 5 ± 7 | 12 ± 6 | ||

| UKF-NB-3 | - | - | 15 ± 6 | 22 ± 8 |

| UKF-NB-3rVCR10 | + | + (C135F) | 78 ± 12* | 83 ± 12* |

| UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 | - | - | 89 ± 9* | 85 ± 7* |

| UKF-NB-3rDOX20 | + | - | 66 ± 13* | 70 ± 6* |

| UKF-NB-2 | - | - | 17 ± 11 | 20 ± 5 |

| UKF-NB-2rVCR10 | + | - | 48 ± 13* | 55 ± 8* |

| UKF-NB-2rCDDP1000 | - | - | 38 ± 7* | 48 ± 10* |

| UKF-NB-2rDOX20 | + | - | 35 ± 9* | 42 ± 9* |

| IMR-32 | - | - | 8 ± 6 | 17 ± 5 |

| IMR-32rVCR10 | + | - | 63 ± 15* | 67 ± 8* |

| IMR-32rCDDP1000 | - | - | 49 ± 7* | 58 ± 6* |

| IMR-32rDOX20 | - | - | 37 ± 8* | 44 ± 14* |

| UKF-NB-4 | + | + (C175F) | 92 ± 9# | 78 ± 15# |

| Be(2)-C | + | + (C135F) | 94 ± 16# | 90 ± 7# |

1 P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression; + = overexpression, - = no overexpression

2 p53 status; + = mutated p53, - = wild-type p53

3 endothelial cells were grown in cancer cell culture supernatants mixed 1:1 with IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS; cell number was determined after 120 h

4 confluent endothelial cell monolayers were incubated with cancer cell culture supernatants mixed 1:1 with IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS; cell number was determined after 48 h

5 IMDM supplemented with 15% FCS, 5% human serum, bFGF 2.5 ng/ml

6 IMDM supplemented with 10% FCS

* P < 0.05 relative to corresponding parental chemosensitive neuroblastoma cell line

# P < 0.05 relative to the parental chmosensitive neuroblastoma cell lines UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-2, and IMR-32.

All cell lines were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medum (IMDM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultivated as described before [21] using IMDM supplemented with 15% FCS and 5% pooled human serum.

Viability assay

HUVEC viability was investigated using the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Caspase activation

Caspase 3/7 activation was measured using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Tube formation assay

Endothelial cellular tube formation was investigated using HUVECs seeded on extracellular matrix (Matrigel, BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) as described before [21].

Western blot

Cells were lysed in Triton X-sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were detected using specific antibodies against β-actin (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany), ERK 1/2, the phosphorylated forms of ERK 1/2 (each from New England Biolabs, Frankfurt am Main, Germany), Akt, or the phosphorylated forms of Akt (all Millipore (Upstate), Schwalbach, Germany) and were visualised by enhanced chemiluminescence using a commercially available kit (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described [22].

Animal experiments

Experiments using the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) were performed using described methods [23]. 106 cells were placed onto the CAM at day 8. Vessel formation was examined at day 12.

Mouse experiments were performed using female NMRI:nu/nu mice as described before [9]. 107 cells were injected subcutaneously together with Matrigel in a total volume of 100 μl. For doxorubicin treatment, the day when xenograft tumours became palpable was defined to be day 1. Tumour sections were stained for apoptotic cells by TUNEL staining and for cell proliferation by ki67 staining using established methods [24,25].

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with all relevant declarations on the use of laboratory animals and with the German Animal Protection Law.

Results

Expression of angiogenesis-associated genes

A pathway analysis was performed in order to detect the most strongly influenced signalling pathways between UKF-NB-3 and its chemoresistant sub-lines UKF-NB-3rVCR10 and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000. Of the 153 pathways mapped at PANTHER, angiogenesis was found to be the fourth most significantly affected signalling pathway (p = 1.87 × 10-4) [see Additional file 1].

Hierarchical cluster analysis and the heatmap indicating expression of angiogenesis-associated ProbeIDs (Figure 1) illustrate a striking and consistent re-arrangement of angiogenesis-related gene expression in the resistant cells. The 39 angiogenesis-related ProbeIDs differentially regulated between UKF-NB-3 and UKF-NB-3rVCR10 cells represent 35 genes [see Additional file 2]. Of these 35 genes, 27 were up-regulated in UKF-NB-3rVCR10 cells in comparison to UKF-NB-3 cells and 8 were down-regulated. The 10 angiogenesis-related ProbeIDs differentially regulated between UKF-NB-3 and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells represent 10 genes [see Additional file 3]. Of these 10 genes, 8 were up-regulated in UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells in comparison to UKF-NB-3 cells and 2 were down-regulated.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associatd genes (taken from PANTHER pathway) in UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells. Data were merged from two independent exeriments each comparing UKF-NB-3 with one chemoresistant cell line. UKF-NB-3a was analysed together with UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-B-3b was analysed together with UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000.

Subsequently to these analyses, we compared angiogenesis signalling between UKF-NB-3 and UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells. Since Applied Biosystems had stopped manufacturing of AB1700 arrays, HGU133 Plus 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix) were used. Results were similar to those obtained from the comparison of UKF-NB-3 with UKF-NB-3rVCR10 and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells. PANTHER pathway analysis indicated angiogenesis to be the fourth most significantly differentially regulated signalling pathway [see Additional file 4]. Hierarchical cluster analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes separated UKF-NB-3 from UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells [see Additional file 5]. 65 angiogenesis-associated genes were found significantly differentially regulated between UKF-NB-3 and UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells. 38 genes were up-regulated in UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells and 27 genes were down-regulated in UKF-NB-3rDOX20 relative to UKF-NB-3 cells [see Additional file 6]. The relatively high number of significantly differentially regulated genes compared to the comparisons of UKF-NB-3 vers. UKF-NB-3rVCR10 or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells most likely results from the different statistical procedures used to analyse HGU133 Plus 2.0 or AB1700 data.

To further investigate the influence of chemoresistance acquisition on the pro-angiogenic potential of cancer cells, a panel of chemsensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines was systematically investigated for their angiogenic phenotypes.

Influence of neuroblastoma cell line supernatants on endothelial cell growth and survival

Neuroblastoma cell lines were grown for seven days. Then medium was removed, cells were washed and protein-free medium was added. After 48 h incubation, supernatants were collected, adjusted to the same protein content, mixed in a 1:1 ratio with fresh IMDM, and FCS (resulting in 10% FCS) was added (unless otherwise noted, all cell culture supernatants were handled following this procedure). HUVECs were trypsinised and suspended in the mixtures of supernatants, fresh IMDM and FCS (without further addition of growth factors). 103 cells suspended in 100 μl of respective medium were seeded per well in 96-well plates. After five days, HUVEC growth was examined by viability assay (Table 1). HUVECs suspended in IMDM plus 10% FCS did not grow (negative control). HUVECs suspended in IMDM plus 15% FCS, 5% pooled human serum, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) 2.5 ng/ml formed vital, closely grown monolayers (positive control). Cell viabilities were calculated relative to positive control. Supernatants from cell lines adapted to cytotoxic drugs induced stronger HUVEC growth than supernatants from parental chemosensitive cells (Table 1). Moreover, the neuroblastoma cell lines UKF-NB-4 and Be(2)-C that were isolated as chemoresistant cell lines from patients materials induced stronger HUVEC growth than the chemosensitive parental cell lines UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-2, or IMR-32. Subsequently, growth kinetics of HUVECs (determined by cell count) incubated with supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells were compared confirming increased growth of HUVECs incubated with supernatants of chemoresistant cells (Figure 2A).

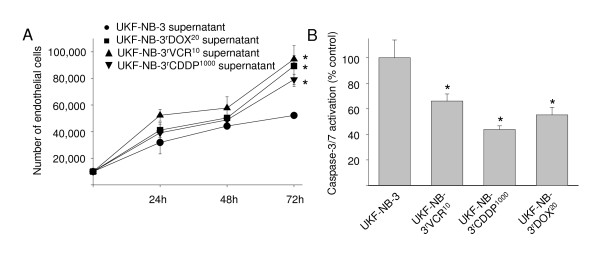

Figure 2.

Influence of neuroblastoma cell culture supernatants on endothelial cell growth and viability. A) Cell growth characteristics of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) incubated with a mixtures of neuroblastoma cell culture supernatants and IMDM (1:1) supplemented with 10% FCS indicated by cell count. B) Caspase 3/7 activation in confluent endothelial cell monolayers incubated with a mixtures of neuroblastoma cell culture supernatants and IMDM (1:1) supplemented with 10% FCS for 48 h. * P < 0.05 relative to endothelial cells incubated with UKF-NB-3 supernatants.

Next, the influence of neuroblastoma cell culture supernatants was examined on HUVEC survival. Confluent HUVEC monolayers were washed and incubated for 48 h with supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells and HUVEC viability was determined. Results revealed increased HUVEC viability in cultures incubated with supernatants of chemoresistant cells (Table 1). Lack of growth factors or nutrients induces apoptosis in endothelial cells [26-28]. Therefore, we investigated caspase 3/7 activation as indicator of apoptosis in confluent HUVEC monolayers incubated for 48 h with supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells. Results indicated decreased caspase activation in HUVECs incubated with supernatants from chemoresistant cells (Figure 2B).

Influence of neuroblastoma cell line supernatants on endothelial cell tube formation

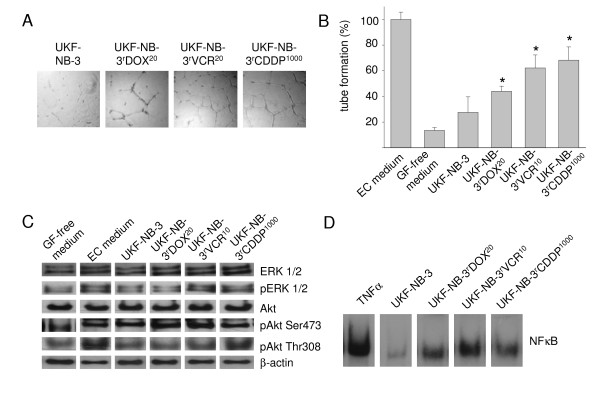

HUVECs were suspended with supernatants of neuroblastoma cell lines and seeded on extracellular matrix (Matrigel). After 16 h, tube formation was determined. Results indicated increased tube formation in HUVECs suspended in supernatants of UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells in comparison to HUVECs suspended in supernatants of the parenal chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cell line (Figure 3A, B). Similar results were detected in the parental cell lines IMR-32 and UKF-NB-2 in comparison to their chemoresistant sub-lines [see Additional file 7]. Using different ratios of supernatants from the cell lines UKF-NB-3rVCR10 or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 and IMDM indicated that the supernatants induce tube formation in a concentration-dependent manner [see Additional file 7].

Figure 3.

Influence of neuroblastoma cell culture supernatants on tube formation and activation of pro-angiogenic signalling pathways in endothelial cells. A) Representative photographs showing tube formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) suspended in 1:1 mixtures of IMDM + 10 FCS and supernatants of parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cells or sublines adapted to vincristine (UKF-NB-3rVCR10), cisplatin (UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000), or doxorubicin (UKF-NB-3rDOX20) 16 h after seeding on extracellular matrix. B) Quantification of tube formation by counting of branching points of HUVEC incubated with 1:1 mixtures of IMDM and supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells + 10% FCS in comparison to endothelial cell medium (EC medium, IMDM + 15% FCS + 5% pooled human serum + bFGF 2.5 ng/ml) and growth factor-free medium (GF-free medium, IMDM + 10% FCS). P < 0.05 relative to endothelial cells incubated with UKF-NB-3 supernatants. C) Representative Western blot showing expression of ERK 1/2, phosphorylated ERK 1/2 (pERK 1/2), Akt, Akt phosphorylated at Ser473 (pAkt Ser473), or Akt phosphorylated at Thr308 (pAkt Thr308) in endothelial cells incubated with 1:1 mixtures of IMDM and supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells + 10% FCS in comparison to EC medium and GF-free medium for 24 h. β-actin was used as loading control. D) Representative EMSA showing nuclear factor κB (NFκB) activation in endothelial cells incubated with 1:1 mixtures of IMDM and supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells + 10% FCS for 24 h. Tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) was used as positive control.

Influence of neuroblastoma cell line supernatants on activation of pro-angiogenic signalling events in endothelial cells

The phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K) - Akt (also known as protein kinase B, PKB) signalling pathway, "classical" mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling via Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK, and activation of nuclear factor κB (NFκB) are involved in angiogenesis signalling in endothelial cells [29-31]. The influence of supernatants of chemoresistant cells on Akt phosphorylation or ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in HUVECs is shown in Figure 3C. Densitometric analysis of Western blot data is given in Additional file 8. Akt may be activated through phosphorylation at Ser473 and/or at Thr308. The supernatants of UKF-NB-3rVCR10 or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells induced enhanced Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in comparison to UKF-NB-3 supernatants. All supernatants of chemoresistant cells caused enhanced NFκB activation relative to supernatants of chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cells (Figure 3D).

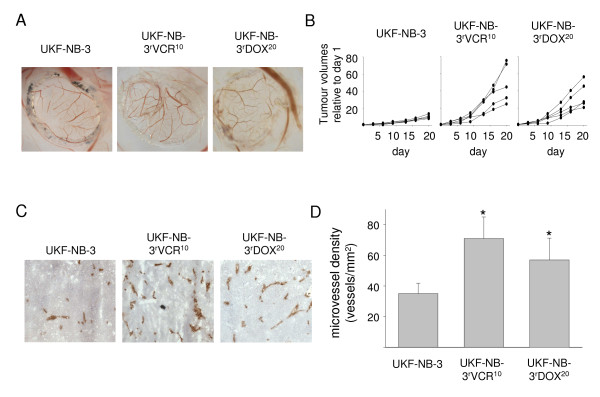

Chemoresistant cancer cells induce increased vessel formation in animal models

Vessel formation was first investigated in vivo in the CAM of fertilised eggs. 106 tumour cells were seeded onto the CAM per egg (eight eggs per cell line) at day 10. Vessel formation was scored by two independent observers at day 14. Results indicated higher vessel formation in chemoresistant (UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rDOX20) cells than in chemosensitive (UKF-NB-3) cells (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Vessel formation induced by neuroblastoma cells in vivo. A) Representative photographs of vessels induced by neuroblastoma cell lines in the chick chorioallantoic membrane. B) Growth curves of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 tumours in nu/nu mice; UKF-NB-3rVCR10 and UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells formed statistically significant larger tumours than UKF-NB-3 cells C) Representative photographs of angiogenesis in UKF-NB-3 or UKF-NB-3rVCR10 xenograft tumours in nu/nu mice indicated by red (anti-CD31 antibody-stained) vessels. D) Microvessel density in UKF-NB-3 or UKF-NB-3rVCR10 xenograft tumours in nu/nu mice. * P < 0.05 relative to UKF-NB-3 tumours.

Vessel formation was further investigated in xenografts formed of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells in female NMRI:nu/nu mice. Tumour take in mice injected with UKF-NB-3rVCR10 cells was 100%, in mice injected with UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells it was 90% while only 10% of UKF-NB-3 cell-injected mice formed tumours. UKF-NB-3rVCR10 cells and UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells also formed considerably bigger and stronger vascularised xenograft tumours than UKF-NB-3 cells (Figure 4B-D).

Increased pro-angiogenic activity of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells is mediated by individual molecular mechanisms

VEGF is a pro-angiogenic factor that has frequently been associated with neuroblastoma angiogenesis [32,33]. However, increased VEGF levels were not consistently found in supernatants of chemoresistant cells [see Additional file 9]. Acute cisplatin treament has been described to induce tumour progression through VEGF expression in paediatric tumour cells including the neuroblastoma cell line SK-N-BE2 [34]. In cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma cells, VEGF expression has not been investigated, yet. Increased VEGF levels were detected in UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells versus UKF-NB-3 cells and in IMR-32rCDDP1000 cells versus IMR-32 cells but not in UKF-NB-2rCDDP10 cells versus UKF-NB-2 cells [see Additional file 9]. Moreover, the pro-angiogenic factors interleukin-8 (IL-8), angiogenin, basic fibroblast growth factor, or tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were not generally found to be increased in supernatants of chemoresistant cells [see Additional file 9]. Two angiogenesis-associated genes (ARHGAP8, FGFR2) were found commonly up-regulated in UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells versus UKF-NB-3 cells [see Additional files 2, 3, 6]. However, these genes were not consistently found up-regulated in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells (data not shown).

Expression of a number of further pro- and anti-angiogenic factors has been suggested to be relevant for neuroblastoma angiogenesis including platelet-derived growth factor α (PDGFα), matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2), MMP-9, erythropoietin (EPO), EPO receptor, activin A, interleukin-6 (IL-6), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP2), pigment epithelial-derived growth factor (PEDGF), secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC), thrombospondin-1, and thrombospondin-2 [33]. However, analysis of gene microarray data from neuroblastoma cell lines did not reveal specific expression of these or other angiogenesis-related genes that would suggest a single common molecular event underlying increased neuroblastoma tumour angiogenesis in all chemoresistant cells (data not shown).

N-myc amplification has also been reported to result in increased neuroblastoma tumour angiogenesis through different mechanisms [33,35-37]. However, UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells showed enhanced pro-angiogenic potential compared to UKF-NB-3 cells although both cell lines do neither differ in N-myc amplification nor in N-myc expression [8,18]. This indicates that the N-myc status may not generally be critical for increased pro-angiogenic potential of chemoresistant cells. Furthermore, the loss of functional p53 during tumourigenesis has been correlated to a more pro-angiogenic tumour phenotype [38]. However, in our experiments pro-angiogenic activity was enhanced in both p53-mutated and p53-wild-type chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells (Table 1). Taken together, the more pro-angiogenic phenotype observed in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells appears to result from different individual shifts in the expression of angiogenesis-associated genes.

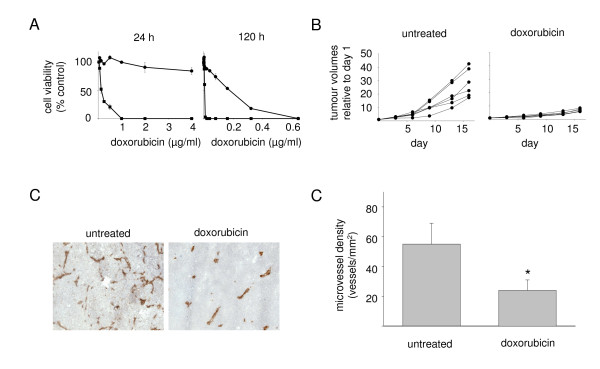

Doxorubicin inhibits tumour angiogenesis and growth of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts

Data had indicated individual changes in the expression of angiogenesis-related genes to be responsible for the proangiogenic phenotype of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells (see above). To investigate if the increased pro-angiogenic activity of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells may be relevant for enhanced growth of chemoresistant neuroblastoma xenografts, doxorubicin-resistant UKF-NB-3rDOX20 neuroblastoma cells were treated with doxorubicin that is known to interfere with angiogenesis by direct influence on endothelial cells [39,40].

Administration of a single dose of doxorubicin 10 mg/kg i.v. into mice results in maximal doxorubicin plasma levels in the range of 500 - 600 ng/ml that decline to doxorubicin plasma levels of 20 - 30 ng/ml 24 h after injection [40-42]. One time application of doxorubicin 8 mg/kg i.v. resulted in intratumoural doxorubicin concentrations of about 10 - 20 ng/ml in a melanoma xenograft model [43]. The doxorubicin IC50 values of UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells are > 4000 ng/ml after a 24 h incubation period and 180.50 ± 22.13 ng/ml after 120 h incubation period. Dose response curves for doxorubicin treatment of UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells are shown in comparison to parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cells in Figure 5A. Consequently, treatment of UKF-NB-3rDOX20 xenograft carrying mice with doxorubicin 8 mg/kg i.v. should not directly affect UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cell viability and tumour growth. Therefore, mice received doxorubicin 8 mg/kg i.v. when tumours became palpable and tumour volumes were observed for 16 days. Then mice were sacrificed and xenograft tumours were examined for vessel density. Doxorubicin strongly reduced UKF-NB-3rDOX20 xenograft growth as well vessel density in the tumours (Figure 5B-D). TUNEL staining indicated an increase in the number of apoptotic cells in doxorubicin-treated (231 ± 61 cells per microscopic field at 200× magnification) vs. non-treated UKF-NB-3rDOX20 (112 ± 22 cells per microscopic field at 200× magnification) xenografts. The fraction of ki67-expressing proliferating cells was higher in non-treated tumours (163 ± 26 cells per microscopic field at 200× magnification) than in doxorubicin-treated tumours (101 ± 14% cells per microscopic field at 200× magnification) indicating decreased proliferation.

Figure 5.

Influence of doxorubicin on viability of neuroblastoma cells, growth of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts, and vessel formation in doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts. A) Dose-response curves of parental chemosensitive neuroblastoma cell cultures (UKF-NB-3; black square) or the doxorubicin-resistant sub-line (UKF-NB-3rDOX20; black dot) after 24 h or 120 h incubation periods. B) Tumour volumes in mice injected with 107 UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells; doxorubicin treatment (8 mg/kg i.v.) was performed at day 1, i.e. when tumours became palpable. C) Representative photographs of angiogenesis in untreated or doxorubicin-treated UKF-NB-3rDOX20 xenograft tumours by red (anti-CD31 antibody-stained) vessels at day 16. D) Microvessel density in untreated or doxorubicin-treated UKF-NB-3rDOX20 xenografts at day 16. * P < 0.05 relative to UKF-NB-3 tumours.

Discussion

Here, we used a bioinformatics-based approach based on transcriptomics data to identify signalling pathways associated with increased malignant behaviour of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Angiogenesis signalling belonged to the top 5 pathways most strongly differentially regulated between chemosensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Systematic evaluation of a panel of neuroblastoma cell lines in cell culture and animal models showed consitently increased pro-angiogenic acivity exerted by chemoresistant cells. These findings are in accordance with previous reports showing that human melanoma and breast cancer cells selected for resistance to chemotherapeutic agents produced higher levels of multiple angiogenic factors [44,45]. Moreover, an increased microvessel density (MVD) was detected in chemotherapy resistant xenograft tumours [44,45].

Selection of cancer stem cells has been suggested to play a role in the enhanced pro-angiogenic activity seen in chemoresistant cancer cells. In lung cancer cells, treatment with cisplatin, doxorubicin, or etoposide resulted in the selection of cancer stem cells as indicated by cell biology and analysis of expression of stemness genes [46]. These chemotherapy-selected cancer stem cells were responsible for the observed increased pro-angiogenic properties of lung cancer cells. In the absence of cytotoxic drugs, lung cancer cell lines returned to their initial phenotype and re-acquired drug sensitivity [46]. In contrast, UKF-NB-3rVCR10 and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells remained chemoresistant and did not loose their pro-angiogenic phenotype even when they were cultivated for up to six months in the absence of drugs (data not shown). This suggests that chemoresistance and pro-angiogenic activity in these cell lines are not consequence of a simple chemotherapy-induced selection of cancer stem cells that are already present in the parental UKF-NB-3 cell line. Moreover, acute cisplatin treatment increased VEGF expression together with expression of the stemness genes Nanog, Bmi-1, and Oct 4 in osteosarcoma (HOS), rhabdomyosarcoma (RH-4) and neuroblastoma (SK-N-BE2) cell lines [46]. However, none of these stemness genes was found up-regulated in UKF-NB-3rVCR10 or UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells relative to UKF-NB-3 cells [see Additional file 10].

The finding that cell culture supernatants from chemoresistant cells exerted stronger pro-angiogenic effects than those from chemosensitive cells suggests that soluble factors contribute to the enhanced pro-angiogenic activity exerted by chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Statistical analysis of the expression of angiogenesis-related genes indicated clear differences between chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cells and the chemoresistant sub-lines UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 (Figure 1) [see Additional files 1, 4, 5]. Obviously, chemoresistance development resulted in a global change of expression of angiogenesis-associated genes towards a more pro-angiogenic phenotype. The resistance-related changes in expression patterns appear to differ between individual chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines. This suggests that the enhanced pro-angiogenic phenotype observed in all chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines in comparison to the chemosensitive cell lines is caused by different (individual) changes in the expression patterns of angiogenesis-associated genes. Notably, hierarchical clustering of expression of angiogenesis-associated genes also clearly discriminated UKF-NB-2 cells from UKF-NB-2rVCR10 and UKF-NB-2rCDDP1000 cells [see Additional file 11], as well as IMR-32 cells from IMR-32rVCR10 cells [see Additional file 12].

The view that individual chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines exert pro-angiogenic effects by individual mechanisms is supported by the results derived from the examination of pro-angiogenic signalling in endothelial cells incubated with supernatants from different neuroblastoma cell lines. Supernatants of chemoresistant UKF-NB-3rDOX20, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells enhanced NFκB activation compared to supernatants of chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 cells However, only supernatants of UKF-NB-3rVCR10 and UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000 cells but not UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells elevated Akt and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells. Based on these differences in the activation of pro-angiogenic signalling events in endothelial cells, it appears plausible that endothelial cell activation might be caused by different chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines by different molecular mechanisms resulting in up- or down-regulation of varying pro- or anti-angiogenic factors.

Possibly, there is an overlap between gene products involved in angiogenesis and gene products relevant in chemoresistance. Indeed, among between the aniogenesis-associated genes that were differentially expressed there are those that are also considered to contribute to chemoresistance. Three arbitrarily chosen examples are BIRC5, MAPK3, and AKT1. BIRC5 (increased expression in UKF-NB-3rVCR10 vs. UKF-NB-3, [see Additional file 2], and in UKF-NB-3rDOX20 vers. UKF-NB-3, [see Additional file 6]) encodes for a protein that is also named survivin and plays a prominent role in apoptosis inhibition and cancer cell chemoresistance [47]. Moreover, BIRC5 expression in cancer cells has been linked to tumour angiogenesis [48] and inhibition of BIRC5 expression in tumour cells decreased tumour angiogenesis [49,50]. MAPK3 (increased expression in UKF-NB-3rVCR10 vs. UKF-NB-3, [see Additional file 2]) encodes for a protein that is also called extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and is a constituent of the "classical" MAP kinase pathway Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK. ERK1 phosphorylation protects cancer cells from different entities against chemotherapy-induced apoptosis [51-53]. Moreover, MAPK3 activation/phosphorylation induces production of pro-angiogenic factors in renal carcinoma cells [54]. AKT1 (increased expression in UKF-NB-3rDOX20 vers. UKF-NB-3, [see additional file 6]) encodes for a protein also called protein kinase B (PKB) that is a central mediator of survival signals transduced by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and is involved in chemoresistance [55-57] as well as in cancer cell expression of pro-angiogenic factors [58-60]. Remarkably, an angiogenesis-associated gene expression signature had been described before to predict the sensitivity of cancer cells to artemisinins, an anti-cancer active group of anti-malaria drugs [61].

The complexicity of pro-angiogenic mechanisms observed in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells is in accordance with other reports demonstrating that pro-angiogenic activity of cancer cells is commonly caused by complex changes in angiogenesis signalling and that inhibition of one pro-angiogenic event may not be enough to interfere with tumour vessel formation [62]. N-myc-amplified neuroblastoma cells that exert pro-angiogenic activity mainly through VEGF have very recently been shown to rapidly develop alternative pro-angiogenic mechanisms when VEGF signalling is inhibited [63]. In addition, up-regulation of multiple pro-angiogenic factors enabled carcinoma cells to escape from angiogenesis inhibition by the three endogenous anti-angiogenic molecules thrombospondin-1, endostatin, and tumstatin [64]. Notably, combination therapy of metastatic breast cancer with paclitaxel and the anti-VEGF-A antibody bevacizumab resulted in prolonged progression-free survival but did not influence overall survival relative to paclitaxel in a phase III trial [65]. In the light of the findings presented here, one may speculate that anti-angiogenic therapy may prolong progression-free survival but that resistance development (to chemotherapy and/or anti-angiogenic therapy) may result in a more aggressive cancer cell phenotype, which might be the reason for the decreased time period observed between tumour re-onset and patients' deaths.

High tumour angiogenesis and high-level expression of pro-angiogenic factors at diagnosis have previously been suggested to be correlated with advanced disease stages in neuroblastoma [32,66,67]. However, the prognostic value of angiogenesis in neuroblastoma at diagnosis is still a matter of debate [68,69]. Notably, analysis of two different data sets reporting on gene expression profiles in tumours from poor outcome or bad outcome N-myc amplified [70] or non-N-myc amplified [71] neuroblastoma patients indicated statistically significant differences in angiogenesis signalling between these groups [see Additional files 13, 14]. To investigate if the increased pro-angiogenic phenotype observed in chemoresistant cells may contribute to tumour progression, xenografts grown from doxorubicin-resistant (UKF-NB-3rDOX20) cells were treated with doxorubicin, an anti-cancer drug that exerts anti-angiogenic activity by direct effect on endothelial cells [39,40]. Tumour vessel formation and growth were strongly reduced by doxorubicin in doxorubicin-resistant xenografts. Although it cannot be concluded without a doubt that the entire effect on xenograft growth can be attributed to inhibition of angiogenesis, microvessel density was statistically reduced supporting the view that inhibition of angiogenesis has definitely contributed. Therefore, these data suggest that increased pro-angiogenic activity of doxorubicin-resistant cells contributes to their more malignant phenotype and that anti-angiogenic strategies that target endothelial cells might represent a therapeutic option for neuroblastoma treatment.

Conclusion

Bioinformatics pathway analysis indicated differences in the expression of angiogenesis-associated genes between chemosensitive and chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines. Cell culture and animal data showed that acquired resistance to different anti-cancer drugs resulted in increased pro-angiogenic activity of neurobastoma cells. The changes in angiogenesis signalling observed in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells are very complex and differ between individual cell lines. Therefore, individual molecular mechanisms appear to be responsible for the enhanced pro-angiogenic activity that was consistently observed in all investigated chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines relative to chemosensitive cells. Doxorubicin treatment of doxorubicin-resistant neuroblastoma xenografts resulted in decreased vessel formation and tumour growth suggesting that the more pro-angiogenic phenotype of chemoresistant cells may contribute to increased malignancy of chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells and that endothelial cell targeting may represent a possibility for therapeutic intervention. The complex nature of the chemoresistance-associated changes responsible for the more pro-angiogenic phenotype strongly stresses the need for an improved understanding of biological processes like angiogenesis on a systems biology level.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MM, JC, and JC jr. were involved in acquisition, conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. DK, TS, and NH were involved in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. SB was involved in design, analysis, and interpretation of data. TS was involved in acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. RB and BM were involved in analysis and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. HWD was involved in conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Supplementary Material

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma cells. Most strongly influenced signalling pathways between chemosensitive (UKF-NB-3) and chemoresistant (UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000) neuroblastoma cells.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the vincristine-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rVCR10.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the cisplatin-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma cells. Most strongly influenced signalling pathways between the chemosensitive neuroblastoma cell line UKF-NB-3 and the doxorubicin-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rDOX20.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in UKF-NB-3 or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the doxorubicin resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rDOX20.

Endothelial cell tube formation induced by supernatants of neuroblastoma cells. Quantification of endothelial cell tube formation induced by supernatants of neuroblastoma cells.

Densitometric analysis of Western blot analyses. Densitometric analysis of Western blot analyses investigating expression of ERK 1/2, phosphorylated ERK 1/2 (pERK 1/2), Akt, Akt phosphorylated at Ser473 (pAkt Ser473), or Akt phosphorylated at Thr308 (pAkt Thr308) in endothelial cells incubated supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells.

Pro-angiogenic factors in the supernatants of neuroblastoma cell lines. Concentrations of selected pro-angiogenic factors in the supernatants of neuroblastoma cell lines.

Expression of stemness genes. Comparison of expression of selected stemness genes in chemoresistant or chemosensitive neuroblastoma cells.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in UKF-NB-2, UKF-NB-2rVCR10, or UKF-NB-2rCDDP1000 cells.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in IMR-32 or IMR-32rVCR10 cells.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma patients' tumours. Signalling pathways most strongly differentially regulated between N-myc amplified neuroblastoma tissues from patients with favourable outcome or poor outcome.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma patients' tumours. Signalling pathways most strongly differentially regulated between non-N-myc amplified neuroblastoma tissues from patients with favourable outcome or poor outcome.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mrs. Eva Bechtold and Mrs. Janette Spitznagel technical assistance.

The work was in part supported by the friendly society "Hilfe für krebskranke Kinder Frankfurt e.V.", its foundation "Frankfurter Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder" and the European Commission (project acronym: SYNLET, contract no. 043312).

Contributor Information

Martin Michaelis, Email: michaelis@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Denise Klassert, Email: d.klassert@kinderkrebsstiftung-frankfurt.de.

Susanne Barth, Email: susanne.barth@blue-drugs.com.

Tatyana Suhan, Email: tanyasuhan@mail.ru.

Rainer Breitling, Email: r.breitling@rug.nl.

Bernd Mayer, Email: bernd.mayer@emergentec.com.

Nora Hinsch, Email: n.hinsch@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Hans W Doerr, Email: h.w.doerr@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Jaroslav Cinatl, Email: ja.cinatl@kinderkrebsstiftung-frankfurt.de.

Jindrich Cinatl, jr, Email: cinatl@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

References

- Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL. Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 2007;369:2106–2120. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris JM, Matthay KK. Molecular biology of neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2264–2279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith KC, Hogarty MD. Targeting programmed cell death pathways with experimental therapeutics: opportunities in high-risk neuroblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AN, Gallick GE. Src, chemoresistance and epithelial to mesenchymal transition: are they related? Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:371–375. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32801265d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbomo H, Michaelis M, Klassert D, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Resistance to cytarabine induces the up-regulation of NKG2D ligands and enhances natural killer cell lysis of leukemic cells. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1402–1410. doi: 10.1593/neo.08972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Chen Z, Wang J, Shao X, Cui Z, Yang C, Zhu Z, Xiong D. Overexpression of cell surface cytokeratin 8 in multidrug-resistant MCF-7/MX cells enhances cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1275–1284. doi: 10.1593/neo.08810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaheta RA, Daher FH, Michaelis M, Hasenberg C, Weich EM, Jonas D, Kotchetkov R, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Chemoresistance induces enhanced adhesion and transendothelial penetration of neuroblastoma cells by down-regulating NCAM surface expression. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaheta RA, Michaelis M, Natsheh I, Hasenberg C, Weich E, Relja B, Jonas D, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Valproic acid inhibits adhesion of vincristine- and cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma tumour cells to endothelium. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1699–1706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Fichtner I, Behrens D, Haider W, Rothweiler F, Mack A, Cinatl J, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Anti-cancer effects of bortezomib against chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Schleithoff ES, Stremmel W, Melino G, Krammer PH, Schilling T. One, two, three--p53, p63, p73 and chemosensitivity. Drug Resist Updat. 2006;9:288–306. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Luna JL. Regulation of pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins and its contribution to cancer progression and chemoresistance. Cell Signal. 2008;20:1921–1926. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi H, Guo N, Kejariwal A, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 6: protein sequence and function evolution data with expanded representation of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007:D247–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RJ, Campbell MJ. Transcription, genomes, function. Trends Genet. 2000;16:409–415. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Cinatl J, Jr, Vogel JU, Cinatl J, Weber B, Rabenau H, Novak M, Kornhuber B, Doerr HW. Long-term productive human cytomegalovirus infection of a human neuroblastoma cell line. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:90–96. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960103)65:1<90::AID-IJC16>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchetkov R, Cinatl J, Blaheta R, Vogel JU, Karaskova J, Squire J, Hernáiz Driever P, Klingebiel T, Cinatl J., Jr Development of resistance to vincristine and doxorubicin in neuroblastoma alters malignant properties and induces additional karyotype changes: a preclinical model. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:36–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchetkov R, Driever PH, Cinatl J, Michaelis M, Karaskova J, Blaheta R, Squire JA, Von Deimling A, Moog J, Cinatl J., Jr Increased malignant behavior in neuroblastoma cells with acquired multi-drug resistance does not depend on P-gp expression. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:1029–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Cinatl J, Anand P, Rothweiler F, Kotchetkov R, von Deimling A, Doerr HW, Shogen K, Cinatl J., Jr Onconase induces caspase-independent cell death in chemoresistant neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2007;250:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Bliss J, Arnold SC, Hinsch N, Rothweiler F, Deubzer HE, Witt O, Langer K, Doerr HW, Wels WS, Cinatl J., Jr Cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma cells express enhanced levels of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and are sensitive to treatment with EGFR-specific toxins. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6531–6537. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinatl J, Jr, Michaelis M, Driever PH, Cinatl J, Hrabeta J, Suhan T, Doerr HW, Vogel JU. Multimutated herpes simplex virus g207 is a potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Neoplasia. 2004;6:725–735. doi: 10.1593/neo.04265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinatl J, Jr, Margraf S, Vogel JU, Scholz M, Cinatl J, Doerr HW. Human cytomegalovirus circumvents NF-kappa B dependence in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;167:1900–1908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoutsi M, Sleeman JP, Wilting J. Interaction of rat tumor cells with blood vessels and lymphatics of the avian chorioallantoic membrane. Microsc Res Tech. 2001;55:100–107. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadendorf D, Kern MA, Artuc M, Pahl HL, Rosenbach T, Fichtner I, Nürnberg W, Stüting S, von Stebut E, Worm M, Makki A, Jurgovsky K, Kolde G, Henz BM. Treatment of melanoma cells with the synthetic retinoid CD437 induces apoptosis via activation of AP-1 in vitro, and causes growth inhibition in xenografts in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1889–1898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtner I, Slisow W, Gill J, Becker M, Elbe B, Hillebrand T, Bibby M. Anticancer drug response and expression of molecular markers in early-passage xenotransplanted colon carcinomas. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber HP, Dixit V, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces expression of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and A1 in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13313–13316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Li W, Gui L, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta P, Law PY, Hebbel RP. VEGF prevents apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells via opposing effects on MAPK/ERK and SAPK/JNK signaling. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:495–504. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Suhan T, Michaelis UR, Beek K, Rothweiler F, Tausch L, Werz O, Eikel D, Zörnig M, Nau H, Fleming I, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Valproic acid induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation and inhibits apoptosis in endothelial cells. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:446–453. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachary I. VEGF signalling: integration and multi-tasking in endothelial cell biology. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1171–1177. doi: 10.1042/BST0311171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo LS, Kurzrock R. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its relationship to inflammatory mediators. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2825–2830. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang BH, Liu LZ. AKT signaling in regulating angiogenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:19–26. doi: 10.2174/156800908783497122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert A, Ikegaki N, Kwiatkowski J, Zhao H, Brodeur GM, Himelstein BP. High-level expression of angiogenic factors is associated with advanced tumor stage in human neuroblastomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1900–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rössler J, Taylor M, Geoerger B, Farace F, Lagodny J, Peschka-Süss R, Niemeyer CM, Vassal G. Angiogenesis as a target in neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida R, Das B, Yeger H, Koren G, Shibuya M, Thorner PS, Baruchel S, Malkin D. Cisplatin treatment increases survival and expansion of a highly tumorigenic side-population fraction by upregulating VEGF/Flt1 autocrine signaling. Oncogene. 2008;27:3923–3934. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzi E, Murphy C, Zoephel A, Rasmussen H, Morbidelli L, Ahorn H, Kunisada K, Tontsch U, Klenk M, Yamauchi-Takihara K, Ziche M, Rofstad EK, Schweigerer L, Fotsis T. N-myc oncogene overexpression down-regulates IL-6; evidence that IL-6 inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth. Oncogene. 2002;21:3552–3561. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm A, von Schuetz V, Christiansen H, Havers W, Papoutsi M, Wilting J, Schweigerer L. High activin A-expression in human neuroblastoma: suppression of malignant potential and correlation with favourable clinical outcome. Oncogene. 2005;24:680–687. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Rychahou PG, Ishola TA, Mourot JM, Evers BM, Chung DH. N-myc is a novel regulator of PI3K-mediated VEGF expression in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2008;27:3999–4007. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro JG, Evans SK, Green MR. Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by p53: a new role for the guardian of the genome. J Mol Med. 2007;85:1175–1186. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoh Y, Li L, Yang M, Jiang P, Moossa AR, Katsuoka K, Hoffman RM. Hair follicle-derived blood vessels vascularize tumors in skin and are inhibited by doxorubicin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2337–2343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amoh Y, Li L, Katsuoka K, Hoffman RM. Chemotherapy targets the hair-follicle vascular network but not the stem cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:11–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DL, Rastatter JC, Colombo T, Long ME. Doxorubicin pharmacokinetics: Macromolecule binding, metabolism, and excretion in the context of a physiologic model. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:1488–1501. doi: 10.1002/jps.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DL, Merz AL, Long ME. Pharmacokinetics of combined doxorubicin and paclitaxel in mice. Cancer Lett. 2005;220:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breistøl K, Hendriks HR, Fodstad O. Superior therapeutic efficacy of N-L-leucyl-doxorubicin versus doxorubicin in human melanoma xenografts correlates with higher tumour concentrations of free drug. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1143–1149. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00074-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lev DC, Onn A, Melinkova VO, Miller C, Stone V, Ruiz M, McGary EC, Ananthaswamy HN, Price JE, Bar-Eli M. Exposure of melanoma cells to dacarbazine results in enhanced tumor growth and metastasis in vivo. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2092–2100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y, Okollie B, Raman V, Vesuna F, Zhao M, Baker SD, Bhujwalla ZM, Artemov D. Contributing factors of temozolomide resistance in MCF-7 tumor xenograft models. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:891–897. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levina V, Marrangoni AM, DeMarco R, Gorelik E, Lokshin AE. Drug-selected human lung cancer stem cells: cytokine network, tumorigenic and metastatic properties. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita AC, Mita MM, Nawrocki ST, Giles FJ. Survivin: key regulator of mitosis and apoptosis and novel target for cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5000–5005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Toyoda M, Shinohara H, Okuda J, Watanabe I, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K, Tenjo T, Tanigawa N. Expression of survivin correlates with apoptosis, proliferation, and angiogenesis during human colorectal tumorigenesis. Cancer. 2001;91:2026–2032. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010601)91:11<2026::AID-CNCR1228>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SP, Jiang XH, Lin MC, Cui JT, Yang Y, Lum CT, Zou B, Zhu YB, Jiang SH, Wong WM, Chan AO, Yuen MF, Lam SK, Kung HF, Wong BC. Suppression of survivin expression inhibits in vivo tumorigenicity and angiogenesis in gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7724–7732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu SP, Cui JT, Liston P, Huajiang X, Xu R, Lin MC, Zhu YB, Zou B, Ng SS, Jiang SH, Xia HH, Wong WM, Chan AO, Yuen MF, Lam SK, Kung HF, Wong BC. Gene therapy for colon cancer by adeno-associated viral vector-mediated transfer of survivin Cys84Ala mutant. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:361–375. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Shen S, Guo J, Chen H, Greenblatt DY, Kleeff J, Liao Q, Chen G, Friess H, Leung PS. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells. J Surg Res. 2006;136:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirmohammadsadegh A, Mota R, Gustrau A, Hassan M, Nambiar S, Marini A, Bojar H, Tannapfel A, Hengge UR. ERK1/2 is highly phosphorylated in melanoma metastases and protects melanoma cells from cisplatin-mediated apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2207–2215. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Huo L, Yang JY, Xia W, Wei Y, Liao Y, Chang CJ, Yang Y, Lai CC, Lee DF, Yen CJ, Chen YJ, Hsu JM, Kuo HP, Lin CY, Tsai FJ, Li LY, Tsai CH, Hung MC. Down-regulation of myeloid cell leukemia-1 through inhibiting Erk/Pin 1 pathway by sorafenib facilitates chemosensitization in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6109–6117. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll VA, Ashcroft M. Regulation of angiogenic factors by HDM2 in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:545–552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KA, Castillo SS, Dennis PA. Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and chemotherapeutic resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5:234–248. doi: 10.1016/S1368-7646(02)00120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporali S, Levati L, Starace G, Ragone G, Bonmassar E, Alvino E, D'Atri S. AKT is activated in an ataxia-telangiectasia and Rad3-related-dependent manner in response to temozolomide and confers protection against drug-induced cell growth inhibition. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:173–183. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon V, Van Themsche C, Turner S, Leblanc V, Asselin E. Akt and XIAP regulate the sensitivity of human uterine cancer cells to cisplatin, doxorubicin and taxol. Apoptosis. 2008;13:259–271. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Koutsilieris M. The Akt pathway: molecular targets for anti-cancer drug development. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:235–256. doi: 10.2174/1568009043333032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen XF, Yang G, Mao W, Thornton A, Liu J, Bast RC, Jr, Le XF. HER2 signaling modulates the equilibrium between pro- and antiangiogenic factors via distinct pathways: implications for HER2-targeted antibody therapy. Oncogene. 2006;25:6986–6996. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C, Meng Q, Cao Z, Shi X, Jiang BH. Regulation of angiogenesis and tumor growth by p110 alpha and AKT1 via VEGF expression. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:56–66. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anfosso L, Efferth T, Albini A, Pfeffer U. Microarray expression profiles of angiogenesis-related genes predict tumor cell response to artemisinins. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006;6:269–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levina V, Su Y, Nolen B, Liu X, Gordin Y, Lee M, Lokshin A, Gorelik E. Chemotherapeutic drugs and human tumor cells cytokine network. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2031–2040. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaghloul N, Hernandez SL, Bae JO, Huang J, Fisher JC, Lee A, Kadenhe-Chiweshe A, Kandel JJ, Yamashiro DJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade rapidly elicits alternative proangiogenic pathways in neuroblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:401–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando NT, Koch M, Rothrock C, Gollogly LK, D'Amore PA, Ryeom S, Yoon SS. Tumor escape from endogenous, extracellular matrix-associated angiogenesis inhibitors by up-regulation of multiple proangiogenic factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1529–1539. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, Dickler M, Cobleigh M, Perez EA, Shenkier T, Cella D, Davidson NE. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meitar D, Crawford SE, Rademaker AW, Cohn SL. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastatic disease, N-myc amplification, and poor outcome in human neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:405–414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribatti D, Surico G, Vacca A, De Leonardis F, Lastilla G, Montaldo PG, Rigillo N, Ponzoni M. Angiogenesis extent and expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 correlate with progression in human neuroblastoma. Life Sci. 2001;68:1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(00)01030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenstein HM, Cohn SL, Crawford S, Meitar D. Angiogenesis in neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2789–2791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.14.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañete A, Navarro S, Bermúdez J, Pellín A, Castel V, Llombart-Bosch A. Angiogenesis in neuroblastoma: relationship to survival and other prognostic factors in a cohort of neuroblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:27–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberthuer A, Berthold F, Warnat P, Hero B, Kahlert Y, Spitz R, Ernestus K, König R, Haas S, Eils R, Schwab M, Brors B, Westermann F, Fischer M. Customized oligonucleotide microarray gene expression-based classification of neuroblastoma patients outperforms current clinical risk stratification. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5070–5078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgharzadeh S, Pique-Regi R, Sposto R, Wang H, Yang Y, Shimada H, Matthay K, Buckley J, Ortega A, Seeger RC. Prognostic significance of gene expression profiles of metastatic neuroblastomas lacking MYCN gene amplification. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1193–1203. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma cells. Most strongly influenced signalling pathways between chemosensitive (UKF-NB-3) and chemoresistant (UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000) neuroblastoma cells.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the vincristine-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rVCR10.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the cisplatin-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma cells. Most strongly influenced signalling pathways between the chemosensitive neuroblastoma cell line UKF-NB-3 and the doxorubicin-resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rDOX20.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in UKF-NB-3 or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells.

Expression analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes. Angiogenesis-related genes that are differentially expressed between the parental chemosensitive UKF-NB-3 neuroblastoma cell line and the doxorubicin resistant sub-line UKF-NB-3rDOX20.

Endothelial cell tube formation induced by supernatants of neuroblastoma cells. Quantification of endothelial cell tube formation induced by supernatants of neuroblastoma cells.

Densitometric analysis of Western blot analyses. Densitometric analysis of Western blot analyses investigating expression of ERK 1/2, phosphorylated ERK 1/2 (pERK 1/2), Akt, Akt phosphorylated at Ser473 (pAkt Ser473), or Akt phosphorylated at Thr308 (pAkt Thr308) in endothelial cells incubated supernatants of UKF-NB-3, UKF-NB-3rVCR10, UKF-NB-3rCDDP1000, or UKF-NB-3rDOX20 cells.

Pro-angiogenic factors in the supernatants of neuroblastoma cell lines. Concentrations of selected pro-angiogenic factors in the supernatants of neuroblastoma cell lines.

Expression of stemness genes. Comparison of expression of selected stemness genes in chemoresistant or chemosensitive neuroblastoma cells.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in UKF-NB-2, UKF-NB-2rVCR10, or UKF-NB-2rCDDP1000 cells.

Hierarchical cluster analysis of expresson of angiogenesis-associated genes. Hierarchical cluster analysis and heatmap showing expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in IMR-32 or IMR-32rVCR10 cells.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma patients' tumours. Signalling pathways most strongly differentially regulated between N-myc amplified neuroblastoma tissues from patients with favourable outcome or poor outcome.

Bioinformatic pathway analysis in neuroblastoma patients' tumours. Signalling pathways most strongly differentially regulated between non-N-myc amplified neuroblastoma tissues from patients with favourable outcome or poor outcome.