Abstract

The 2009 flu outbreak in humans, known as "swine influenza" or H1N1 influenza A, refers to influenza A due to a new H1N1 strain called swine-origin influenza virus A (S-OIV). The new swine flu virus is actually a genetic mixture of two strains, both found in swine, of unknown origin. S-OIV can be transmitted from human to human and causes the normal symptoms of influenza. Prevention of swine influenza spread among humans includes use of standard infection control measures against influenza and constitutes the main scope of World Health Organization. For the treatment of S-OIV influenza oseltamivir and zanamivir are effective in most cases. Prophylaxis against this new flu strain is expected through a new vaccine, which is not available yet. Worldwide extension of S-OIV is a strong signal that a pandemic is imminent and indicates that response actions against S-OIV must be aggressive.

Keywords: swine influenza, H1N1 influenza virus A, infection control, oseltamivir, zanamivir

Worldwide, more and more countries are concerned about swine influenza (pig flu) as scientists try to learn more about this emerging disease. Titles such as "a new flu pandemic" or "deadly flu" are in the first pages of most newspapers and websites. Outbreaks of this infectious new strain of influenza virus have proved deadly in some places and relatively benign in others.

The story started on middle April 2009, when US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that two cases of febrile respiratory illness in children in southern counties of California had been caused by infection due to a genetically similar swine influenza virus A (H1N1)1. Virus contained a unique combination of gene segments, not reported previously, among swine and human influenza viruses. Neither child had known contact with pigs, resulting in concern that human-to-human transmission might have occurred. Besides, swine influenza A viruses of the same strain as those in the US patients were confirmed among specimens from patients in Mexico2. The new H1N1 strain was called swine-origin influenza virus A (S-OIV)3. World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC expressed serious concerns about the S-OIV outbreak, and worried that it might become a worldwide flu pandemic.

Possible source of the virus

The outbreak was probably detected in Mexico City first, where surveillance began picking up a surge in cases of influenza-like illness starting on March 2009. The surge was assumed by Mexican authorities to be late-season flu, which usually coincides with a mild influenza-virus B peak, until middle April, when CDC alert concerning two isolated cases of a novel swine flu was reported in the media. An international team of researchers suggested that the H1N1 strain responsible for the current outbreak first evolved around September 2008 and circulated in the human population for several months before the first cases were detected4.

There is a scenario in which an industrial pig farm in the central Mexican state of Veracruz may be the likely source of the virus. The virus seems to have evolved to a stronger form because of the abuse of antibiotics, which have been used to keep the pigs alive in the extreme conditions needed to maximize profit. However, many researchers believe that currently the proximate source of the virus is unknown4.

SOIVs outbreak

An update of WHO website on May 21, 2009, showed 41 countries having officially reported 11,034 human cases of influenza A (H1N1) infection, including Greece5. The total mortality rate is 0.77% (85 deaths). Mexico has reported 3892 laboratory confirmed cases of infection, including 75 deaths (mortality rate 1.93%). The US have reported 5710 laboratory confirmed cases, including 8 deaths (mortality rate 0.14%). Canada has reported 719 laboratory confirmed cases, including one death (mortality rate 0.14%). Costa Rica has reported 20 laboratory confirmed cases, including one death (mortality rate 5%). In addition, the following countries have reported laboratory confirmed cases with no deaths (in parenthesis the number of cases): Japan (259), Spain (111), United Kingdom (109), Panama (69), France (16), Germany (14), Colombia (12), Italy (10), New Zealand (9), Brazil (8), China (8), Israel (7), El Salvador (6), Belgium (5), Chile (5), Cuba (4), Guatemala (4), Australia (3), Netherlands (3), Norway (3), Peru (3), Republic of Korea (3), Sweden (3), Finland (2), Malaysia (2), Poland (2), Thailand (2), Turkey (2), Argentina (1), Austria (1), Denmark (1), Ecuador (1), Greece (1), India (1), Ireland (1), Portugal (1) and Switzerland (1). However, the number of newly confirmed cases increases day by day including new countries.

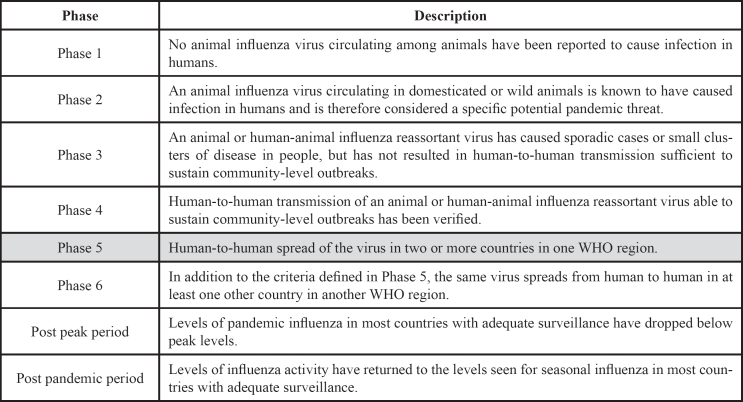

The WHO raised its alert level to Phase 5, one level below an official pandemic. Specifically, the declaration of Phase 5 is a strong signal that a pandemic is imminent and that the time to finalize the organization, communication, and implementation of the planned measures is short. A pandemic (from Greek [pan] = all + [demic] = people) is a human-to-human spread of the virus in two or more countries in one WHO region and at least one other country in another WHO region (Table 1). According to the WHO, a pandemic can start when three conditions have been met: a) emergence of a disease new to a population, b) agents infect humans causing serious illness, and c) agents spread easily and sustainably among humans6.

Table 1. World Health Organization (WHO) phases of a pandemic6. The WHO has currently raised its alert level to Phase 5 outbreak for swine influenza.

Historical context

Influenza constitutes a zoonosis of pigs that was first recognized during the Spanish influenza pandemic of 19181919. Swine influenza in humans was initially described as illness resulting in frequent outbreaks of influenza in families immediately followed by illness in their swine herds and vice versa7. Influenza virus was first isolated from pigs in 1920-30s, with the virus isolated from humans several years later. However, the first isolation of a swine influenza virus from a human occurred in 19748, confirming the speculation that swine-origin influenza viruses could infect humans. Pigs are thought to have an important role in inter-species transmission of influenza, because they have receptors to both avian and human influenza virus strains9. Consequently, they have been considered a possible mixing vessel in which genetic material can be exchanged, with the potential to result in novel progeny viruses to which humans are immunologically naive and highly susceptible10.

Classification

Influenza viruses A, B and C are the 3 genera of influenza viruses that can cause human flu. Among these viruses, type A is common in pigs, type C is rare and type B has not been reported in pigs11. Within A and C, the strains found in pigs and humans are largely distinct, although due to reassortment there have been transfers of genes among strains crossing swine, avian and human species boundaries12.

Swine influenza is known to be caused in pigs mainly by 3 influenza A subtypes H1N1, H3N2 and H1N211. The 2009 flu outbreak is due to a new strain of subtype H1N1 not previously reported in pigs. The new strain was initially described as apparent reassortment of at least 4 strains of influenza A virus subtype H1N1, including one strain endemic in humans, one endemic in birds, and two endemic in swine. Subsequent analysis suggested it was a reassortment of only two strains, both found in swine. Although initial reports identified the new strain as swine influenza (ie, a zoonosis originating in swine), its origin is unknown13.

Spread

The spread of S-OIV flu possibly occurs in the same way that seasonal flu spreads. Flu viruses spread mainly from person to person through coughing or sneezing of people with influenza7. Sometimes people may become infected by touching items with flu viruses on them and then touching their mouth, nose or eyes. Transmission of influenza from swine to humans who work with swine has been documented14. In addition, spread from human to swine also occurs. With seasonal flu, studies have shown that people may be contagious one day before they develop symptoms to up to 7 days after they get sick. Children, especially younger children, and immunocompromised patients may be contagious for longer periods.

H1N1 viruses do not spread by food. Eating properly handled and cooked pork or pork products is safe1,7,15. In addition, tap water pre-treated by conventional disinfection processes does not likely pose a risk for transmission of influenza viruses. Free chlorine levels typically used in drinking water or recreational water pre-treatment are adequate to inactivate highly pathogenic influenza viruses. Currently, there are no documented human cases of influenza caused by exposure to influenza-contaminated drinking water or swimming pool water.

Clinical symptoms

The symptoms of this S-OIV influenza in people are similar to the symptoms of regular human flu and include fever, cough, sore throat, body aches, headache, chills and fatigue. A significant number of people who have been infected with S-OIV also have reported diarrhea and vomiting7. In a recent analysis of 642 confirmed cases, the commonest clinical symptoms were fever in 94% of patients, cough in 92%, sore throat in 66%, diarrhea and vomiting in 25%, respectively16. Unfortunately, severe illness and death has occurred as a result of infection by S-OIV2,16. In seasonal flu, there are certain people that are at higher risk of serious flu-related complications. These include young children, pregnant women, people with chronic medical conditions and people 65 years and older. At this time it is unknown whether certain groups of people are at greater risk of serious flu-related complications from infection due to S-OIV. However, in a recent study, 60% of patients were <18 years of age suggesting that children and young adults may be more susceptible to S-OIV infection than are elderly persons16. This observation may be due to differences in social networks resulting to a delayed transmission to older persons. In addition, it is also possible that older persons may have some level of cross-protection from preexisting antibodies against S-OIV infection16.

Diagnosis

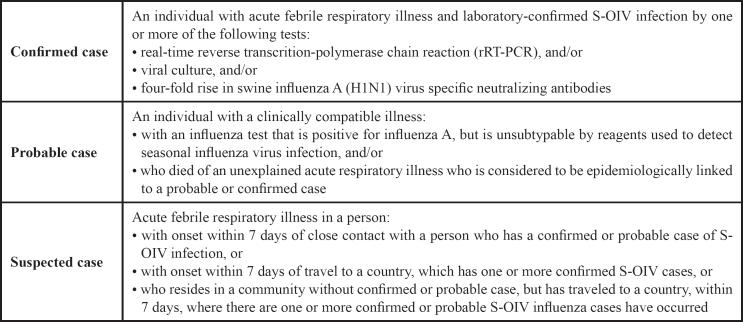

Clinicians should consider swine influenza as well as seasonal influenza virus infections in the differential diagnosis for patients who have febrile respiratory illness and who: 1) live in USA, Mexico and all other countries with several confirmed cases or traveled to these countries 2) are residents of a country without confirmed or probable case but have recently traveled to USA, Mexico and all other countries with several confirmed cases, 3) have been in contact with persons who had had febrile respiratory illness and had been in one of the above countries during the 7 days preceding their illness onset. Any unusual case of febrile respiratory illness elsewhere also should be investigated2,17. Currently, no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared tests specifically for the S-OIV strain exist in the US or elsewhere. CDC has developed the real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) Swine Flu Panel followed by many other countries worldwide, with a purpose to expand and maintain the operational capabilities of public health or other qualified laboratories by providing a detection tool for the presumptive presence of S-OIV. Medical history, rRT-PCR, viral culture and four-fold rise in swine influenza A (H1N1) virus specific neutralizing antibodies, constitute the cornerstones for S-OIV influenza diagnosis. The case definition for infection due to S-OIV is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Case definitions for infection due to swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus (S-OIV)3,17.

Prevention and treatment

There is currently no vaccine available to protect against S-OIV influenza18. Recommendations to prevent infection by the virus consist of the standard personal precautions against influenza19. These include a) frequent washing of hands with soap and water or with alcohol-based hand solutions, especially after touching potentially contaminated items; b) covering the nose and mouth with a tissue during cough or sneeze and avoiding touching eyes, nose or mouth, because germs spread this way; avoiding close contact with sick people and staying home during illness for 7 days after symptoms begin or until symptom-free for 24 hours, to keep from infecting others and spreading the virus further. Finally, following public health advice regarding school closures and avoidance of crowds and other social distancing measures is necessary action.

For the treatment and prophylaxis of S-OIV influenza oseltamivir and zanamivir can be used. The S-OIV is resistant to amantadine and rimantadine20. Oseltamivir is FDA-approved for treatment and prevention of influenza in adults and children aged ≥1 year. Zanamivir is FDAapproved for treatment of influenza in adults and children aged ≥7 years who have been symptomatic for <2 days, and for prevention of influenza in adults and children aged ≥5 years. In the case of S-OIV influenza, oseltamivir can be used for treatment in children aged <1 year and for prevention in children aged 3 months-1 year20. Under the scope and conditions of current pandemic, mass dispensing of both antiviral medications will be allowed.

FDA has authorized use of certain respirators to help reduce exposure to pathogenic biological airborne particulates during a public health emergency involving S-OIV. Respirators should be considered for use by persons for whom close contact with an infectious person is unavoidable. This can include selected individuals who must care for a sick person (e.g., family member with a respiratory infection) at home3. However, the UK Health Protection Agency considers facial masks unnecessary for the general public.

Conclusion

Response actions against S-OIV must be aggressive, although may vary across countries and communities depending on local circumstances. Communities, businesses, places of worship, schools and individuals can all take action to slow the spread of this outbreak. Information is insufficient to make recommendations on the use of the antivirals in prevention and treatment of S-OIV infection. In addition, until a new vaccine against S-OIV becomes available, avoidance of viral spreading is the most appropriate way to prevent a new pandemic.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children-Southern California, March-April. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:400–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Infections - California and Texas, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:435–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: infections with a swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus-United States and other countries, April 28, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:431–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J, Enserink M. Infectious diseases. As swine flu circles globe, scientists grapple with basic questions. Science. 2009;324:572–573. doi: 10.1126/science.324_572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO):Influenza A(H1N1) World Health Organization (WHO); [24. May 10, 2009]. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_05_21/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Current WHO phase of pandemic alert. World Health Organization (WHO); Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/phase/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers KP, Olsen CW, Gray GC. Cases of swine influenza in humans: a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1084–1088. doi: 10.1086/512813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith TF, Burgert EO, Jr, Dowdle WR, Noble GR, Campbell RJ, Van Scoy RE. Isolation of swine influenza virus from autopsy lung tissue of man. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:708–710. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197603252941308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T, Couceiro JN, Kelm S, et al. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. J Virol. 1998;72:7367–7373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7367-7373.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:152, 179. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.152-179.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Reeth K. Avian and swine influenza viruses: our current understanding of the zoonotic risk. Vet Res. 2007;38:243, 260. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2006062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bouvier NM, Palese P. The biology of influenza viruses. Vaccine. 2008;26:49, 53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Greenbaum B, Rabadan R. The origin of the recent swine influenza A(H1N1) virus infecting humans. Eurosurveillance. 2009:4–19193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray GC, Mc Carthy T, Capuano AW, Setterquist SF, Olsen CW, Alavanja MC. Swine workers and swine influenza virus infections. Emerg Infects Dis. 2007;13:1871–1878. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.061323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wells DL, Hopfensperger DJ, Arden NH, et al. Swine influenza virus infections. Transmission from ill pigs to humans at a Wisconsin agricultural fair and subsequent probable person-to-person transmission. JAMA. 1991;265:478–481. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A(H1N1) Virus Investigation Team. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;361 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID: 19423869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization (WHO):WHO case definitions for swine flu. World Health Organization (WHO); Available at: www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/WHO_case_definitions.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update Influenza activity -United States, September 28, 2008-April 4, 2009, and composition of the 2009-10 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch JP, Walsh EE. Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:144–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-976487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Update: drug susceptibility of swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) viruses, April 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:433–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]