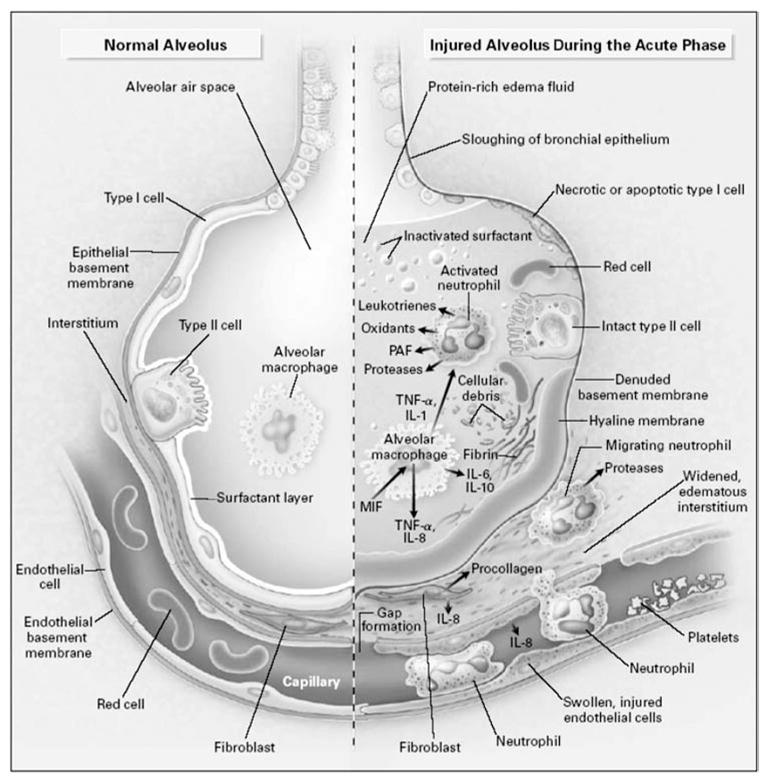

Fig 1.

The normal alveolus (left-hand side) and the injured alveolus in the acute phase of acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. In the acute phase of the syndrome (right-hand side), there is sloughing of both the bronchial and alveolar epithelial cell, with the formation of protein-rich hyaline membranes on the denuded basement membrane. Neutrophils are shown adhering to the injured capillary endothelium and marginating through the interstitium into the air space, which is filled with protein-rich edema fluid. In the air space, an alveolar macrophage is secreting cytokines, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, which act locally to stimulate chemotaxis and activate neutrophils. IL-1 can also stimulate the production of extracellular matrix by fibroblasts. Neutrophils can release oxidants, proteases, leukotrienes, and other proinflammatory molecules, such as platelet-activating factor (PAF). A number of anti-inflammatory mediators are also present in the alveolar milieu, including IL-1-receptor antagonist, soluble TNF receptor, autoantibodies against IL-8, and cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-11 (not shown). The influx of protein-rich edema fluid into the alveolus has led to the inactivation of surfactant. MIF denotes macrophage inhibitory factor. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher [146]. Copyright © 2000 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.