Abstract

In addition to protecting epithelial cells from mechanical stress, keratins regulate cytoarchitecture, cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and organelle transport. In this issue, Vijayaraj et al. (2009. J. Cell Biol. doi:10.1083/jcb.200906094) expand our understanding of how keratin proteins participate in the regulation of protein synthesis through their analysis of mice lacking the entire type II keratin gene cluster.

Keratins are members of the intermediate filament family. They form intricate cytoskeletal networks via the assembly and organization of 10–12-nm filaments, whose formation is initiated through coiled-coil interactions between a type I keratin (e.g., K18 and -19) and a type II keratin (e.g., K8; Kim and Coulombe, 2007). Most keratin proteins have been shown to contribute to the protection of cells and tissues from mechanical and nonmechanical stresses (Toivola et al., 2005; Kim and Coulombe, 2007). Whereas the large number of keratin genes (n = 54; Schweizer et al., 2006) and the heteropolymerization-based assembly of their protein products should in part serve the purpose of modulating the viscoelastic properties of keratin networks to assist various cellular needs, common sense dictates that there should be additional roles for these proteins. Not surprisingly, efforts over the last decade have implicated keratin proteins in several nontraditional functions, including cytoarchitecture, proliferation and growth, apoptosis, and organelle transport, to name a few (Toivola et al., 2005; Kim and Coulombe, 2007). Yet, the high homology between several keratin proteins along with their overlapping distribution in epithelia has limited researchers' progress toward uncovering the full range of keratin function in vivo (Baribault et al., 1994; Tamai et al., 2000; McGowan et al., 2002; Kerns et al., 2007). In this issue, Vijayaraj et al. report on the ultimate bypass of redundancy by eliminating all keratin filaments via the generation of a mouse strain lacking all type II keratins (KtyII−/− mice). The study of these mice, which are viable until embryonic day 9.5, led to the discovery of a novel mechanism through which keratin proteins regulate protein synthesis and cell growth (Kim et al., 2006, 2007; Galarneau et al., 2007). The authors' findings also showcase the recent conceptual and technical advances of chromosome engineering in the mouse genome.

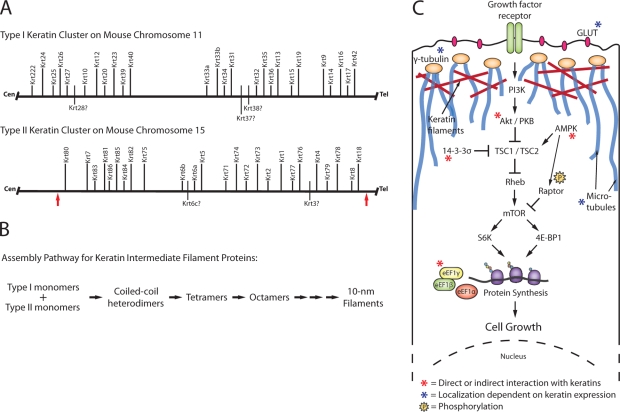

For over a decade, the Cre-loxP site-specific recombination system has been a popular method to generate targeted conditional knockout embryonic stem (ES) cells and mice. Although recombination efficiency is inversely proportional to the distance between loxP sites, larger chromosomal rearrangements have been successfully engineered into mouse ES cells using Cre-loxP (Ramírez-Solis et al., 1995). Generating such targeting vectors is cumbersome using traditional cloning methods. This said, DNA recombineering eliminates many of the constraints of finding unique restriction enzyme sites in genomic DNA sequences (Liu et al., 2003). Also, an Sv129 bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library generated from AB2.2 ES cells makes it easier to obtain large genomic sequences or even target ES cells directly with loxP-containing BACs (Liu et al., 2003; Adams et al., 2005). Finally, the Mutagenic Insertion and Chromosome Engineering Resource (MICER), a library of ready-made targeting vectors spread throughout the mouse genome, is now available (Adams et al., 2004). Vijayaraj et al. (2009) used MICER vectors to remove the entire 0.68-Mb keratin type II cluster on mouse chromosome 15 (Fig. 1 A). Owing to the interdependency of type I and II keratins for 10-nm filament assembly (Fig. 1 B), the resulting KtyII−/− mice represent the first successful elimination of all keratin filaments from an organism as complex as a mouse.

Figure 1.

Genome organization, assembly, and epithelial function of keratins. (A) Arrangement of keratin clusters in the mouse genome. Human keratin genes that have not been identified or annotated in the mouse genome are shown on the bottom side and marked with a question mark. The arrows mark the boundaries of the region deleted by Vijayaraj et al. (2009) on mouse chromosome 15. (B) Summary of the multistep pathway through which type I and II keratin protein monomers polymerize to form 10-nm filaments. The antiparallel docking of the lollipop-shaped coiled-coiled dimers along their lateral surfaces generates structurally apolar tetramers and accounts for the lack of polarity of assembled keratin intermediate filaments. For all steps in the pathway, the forward (assembly promoting) reaction is heavily favored in vitro (Kim and Coulombe, 2007). (C) Keratins influence the localization and function of many cellular components. As highlighted here, keratins interact with and modulate the mTOR pathway in several ways, both in skin keratinocytes and gut epithelial cells, and regulate the localization of microtubules, γ-tubulin, and GLUT transporters in polarized epithelia. Components are not drawn to scale in this schematic.

KtyII−/− embryos display severe growth retardation and die midgestation (Baribault et al., 1993; Hesse et al., 2000; Tamai et al., 2000). Smaller cell size has been observed previously in K17−/− skin keratinocytes and K8−/− liver hepatocytes, correlating with altered Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling (Fig. 1 C) and a reduction in bulk protein synthesis (Kim et al., 2006; Galarneau et al., 2007). Although K17 appears to modulate the mTOR pathway through its physical interaction with 14-3-3–σ in keratinocytes (Fig. 1 C; Kim et al., 2006), the mechanism for how K8 influences protein synthesis in hepatocytes is less clear but appears to integrate responses to both insulin and integrin stimulation (Galarneau et al., 2007). Loss of K8 is also associated with an increase in Akt activity (Galarneau et al., 2007), which is contrary to the findings in the K17−/− setting (Kim et al., 2006), calling into question whether the two settings use the same mechanism to modulate mTOR signaling. Vijayaraj et al. (2009) uncover yet another path through which keratins are able to influence protein synthesis. The authors find that loss of all keratin filaments causes mislocalization of GLUT transporters and disruption of glucose homeostasis through AMP kinase (AMPK) activation. In addition, the authors report that in the absence of the keratin network, AMPK phosphorylates Raptor, which then interacts with mTOR to repress protein synthesis and hamper cell growth (Fig. 1 C). These findings further the evidence for an important role of keratin proteins (or filaments) in the regulation of translation and epithelial cell growth. However, they also raise the question of whether keratins affect mTOR signaling via an as of yet unknown, common denominator or whether several mechanisms come together, perhaps in a cell type– and context-dependent fashion, to achieve the same downstream effect.

Unlike actin and microtubules, keratin filaments are not believed to possess intrinsic polarity (Fig. 1 B). However, K8/K18 and/or K8/K19 filaments play a significant role in maintaining apicobasal compartmentalization in simple epithelial linings in both the small intestine (Ameen et al., 2001; Oriolo et al., 2007) and colon of adult mice (Toivola et al., 2004) and have also been implicated in organelle transport (Toivola et al., 2005; Kim and Coulombe, 2007). The mechanism or mechanisms accounting for this surprising influence of keratins on the establishment and maintenance of spatial order in epithelial cells are unknown. Ameen et al. (2001) and Oriolo et al. (2007) recently made a dent in this mystery by showing that K8/K18 filaments are necessary for the proper localization of γ-tubulin to the apical compartment in polarized epithelial cells, thereby participating in the organization of noncentrosomic microtubules (note: the interested reader should examine a recent study by Bocquet et al. [2009], which shows a role for neuronal intermediate filaments in tubulin polymerization in axons). Similar to previous observations made in K8−/− mice (Ameen et al., 2001; Toivola et al., 2004), Vijayaraj et al. (2009) show that apical proteins, particularly GLUT1 and -3, are mislocalized in KtyII−/− embryonic epithelia. However, in this instance, microtubule organization appears to be intact. Although the authors' experimental findings again nicely demonstrate a role for keratin proteins in the establishment of polarity in simple epithelial settings, the underlying mechanism or mechanisms still need to be ascertained.

The mouse model generated by Vijayaraj et al. (2009) has important implications for the field of keratin biology and intermediate filaments in general. It will allow researchers to address central questions about the contributions of keratins during development and tissue homeostasis unencumbered by the redundancy of properties and functions among members of this large family. The availability of tissue- or cell type–specific promoters makes it possible to express the Cre recombinase in specific epithelial settings, thereby promoting the elimination of keratins in a more restricted fashion. It will be interesting to see how the total loss of keratin filaments affects different tissues and subpopulations of cells, highlighting essential functions and perhaps uncovering previously unappreciated roles for keratins in complex cellular processes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant AR44232 from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Adams D.J., Biggs P.J., Cox T., Davies R., van der Weyden L., Jonkers J., Smith J., Plumb B., Taylor R., Nishijima I., et al. 2004. Mutagenic insertion and chromosome engineering resource (MICER).Nat. Genet. 36:867–871 doi:10.1038/ng1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams D.J., Quail M.A., Cox T., van der Weyden L., Gorick B.D., Su Q., Chan W.I., Davies R., Bonfield J.K., Law F., et al. 2005. A genome-wide, end-sequenced 129Sv BAC library resource for targeting vector construction.Genomics. 86:753–758 doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameen N.A., Figueroa Y., Salas P.J. 2001. Anomalous apical plasma membrane phenotype in CK8-deficient mice indicates a novel role for intermediate filaments in the polarization of simple epithelia.J. Cell Sci. 114:563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribault H., Price J., Miyai K., Oshima R.G. 1993. Mid-gestational lethality in mice lacking keratin 8.Genes Dev. 7:1191–1202 doi:10.1101/gad.7.7a.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baribault H., Penner J., Iozzo R.V., Wilson-Heiner M. 1994. Colorectal hyperplasia and inflammation in keratin 8-deficient FVB/N mice.Genes Dev. 8:2964–2973 doi:10.1101/gad.8.24.2964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet A., Berges R., Frank R., Robert P., Peterson A.C., Eyer J. 2009. Neurofilaments bind tubulin and modulate its polymerization.J. Neurosci. 29:11043–11054 doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1924-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galarneau L., Loranger A., Gilbert S., Marceau N. 2007. Keratins modulate hepatic cell adhesion, size and G1/S transition.Exp. Cell Res. 313:179–194 doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M., Franz T., Tamai Y., Taketo M.M., Magin T.M. 2000. Targeted deletion of keratins 18 and 19 leads to trophoblast fragility and early embryonic lethality.EMBO J. 19:5060–5070 doi:10.1093/emboj/19.19.5060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns M.L., DePianto D., Dinkova-Kostova A.T., Talalay P., Coulombe P.A. 2007. Reprogramming of keratin biosynthesis by sulforaphane restores skin integrity in epidermolysis bullosa simplex.Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:14460–14465 doi:10.1073/pnas.0706486104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Coulombe P.A. 2007. Intermediate filament scaffolds fulfill mechanical, organizational, and signaling functions in the cytoplasm.Genes Dev. 21:1581–1597 doi:10.1101/gad.1552107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Wong P., Coulombe P.A. 2006. A keratin cytoskeletal protein regulates protein synthesis and epithelial cell growth.Nature. 441:362–365 doi:10.1038/nature04659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kellner J., Lee C.H., Coulombe P.A. 2007. Interaction between the keratin cytoskeleton and eEF1Bgamma affects protein synthesis in epithelial cells.Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14:982–983 doi:10.1038/nsmb1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P., Jenkins N.A., Copeland N.G. 2003. A highly efficient recombineering-based method for generating conditional knockout mutations.Genome Res. 13:476–484 doi:10.1101/gr.749203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan K.M., Tong X., Colucci-Guyon E., Langa F., Babinet C., Coulombe P.A. 2002. Keratin 17 null mice exhibit age- and strain-dependent alopecia.Genes Dev. 16:1412–1422 doi:10.1101/gad.979502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriolo A.S., Wald F.A., Canessa G., Salas P.J. 2007. GCP6 binds to intermediate filaments: a novel function of keratins in the organization of microtubules in epithelial cells.Mol. Biol. Cell. 18:781–794 doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Solis R., Liu P., Bradley A. 1995. Chromosome engineering in mice.Nature. 378:720–724 doi:10.1038/378720a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer J., Bowden P.E., Coulombe P.A., Langbein L., Lane E.B., Magin T.M., Maltais L., Omary M.B., Parry D.A., Rogers M.A., Wright M.W. 2006. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins.J. Cell Biol. 174:169–174 doi:10.1083/jcb.200603161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai Y., Ishikawa T., Bösl M.R., Mori M., Nozaki M., Baribault H., Oshima R.G., Taketo M.M. 2000. Cytokeratins 8 and 19 in the mouse placental development.J. Cell Biol. 151:563–572 doi:10.1083/jcb.151.3.563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola D.M., Krishnan S., Binder H.J., Singh S.K., Omary M.B. 2004. Keratins modulate colonocyte electrolyte transport via protein mistargeting.J. Cell Biol. 164:911–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toivola D.M., Tao G.Z., Habtezion A., Liao J., Omary M.B. 2005. Cellular integrity plus: organelle-related and protein-targeting functions of intermediate filaments.Trends Cell Biol. 15:608–617 doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayraj P., Kröger C., Reuter U., Windoffer R., Leube R.E., Magin T.M. 2009. Keratins regulate protein biosynthesis through localization of GLUT1 and -3 upstream of AMP kinase and Raptor.J. Cell Biol. 187:175–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]