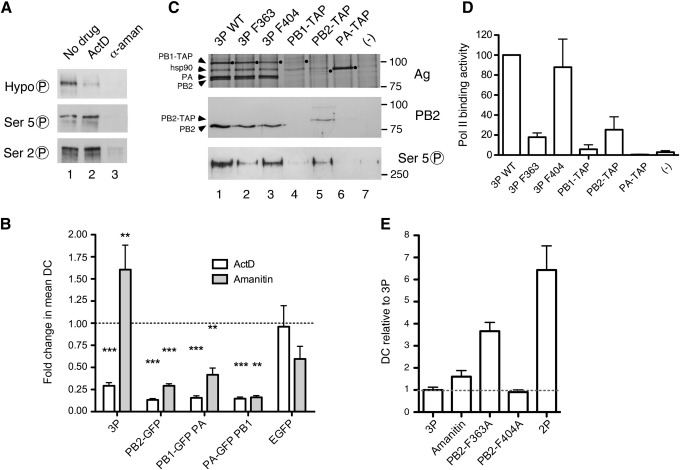

Fig. 5.

Role of cellular transcription in the nuclear dynamics of the viral polymerase. (A) 293T cells were mock-treated (−), treated with 5 μg/ml ActD for 1 h or with 5 μg/ml α-amanitin for 9 h, lysed and analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with sera specific for modified forms of the CTD of RNA Pol II as indicated. (B) 293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for the indicated GFP-tagged viral polymerase proteins (3P complex tagged with PB2-GFP) or GFP, 24 h post transfection treated or mock treated with RNA Pol II inhibitors as in (A) and fluorescent cells then analysed by FRAP. The fold change in mean DCs of the drug-treated samples relative to the corresponding untreated samples are plotted. A Student's two-tailed t-test, assuming equal variance, was used to compare DCs of drug-treated and untreated samples and returned p-values (⁎⁎p < 0.01, ⁎⁎⁎p < 0.001) describing the probability of the compared data being equal. (C) 293T cells were transfected with expression vectors for the indicated TAP-tagged viral polymerase proteins (3P complex tagged with PB1-TAP) and 42 h later cell extracts fractionated by IgG sepharose chromatography followed by SDS-PAGE and (top panel) silver staining; migration of TAP-tagged subunits indicated by black spots, (middle panel) western blotting for PB2 or (lower panel) serine 5 phosphorylated Pol II. (D) Bound Pol II from three independent experiments was quantified by densitometry and plotted as the mean ± SEM relative to WT 3P (100%). (E) The fold change in mean DC values of the indicated samples relative to WT 3P are plotted. The 2P value is from PB1-GFP + PA.