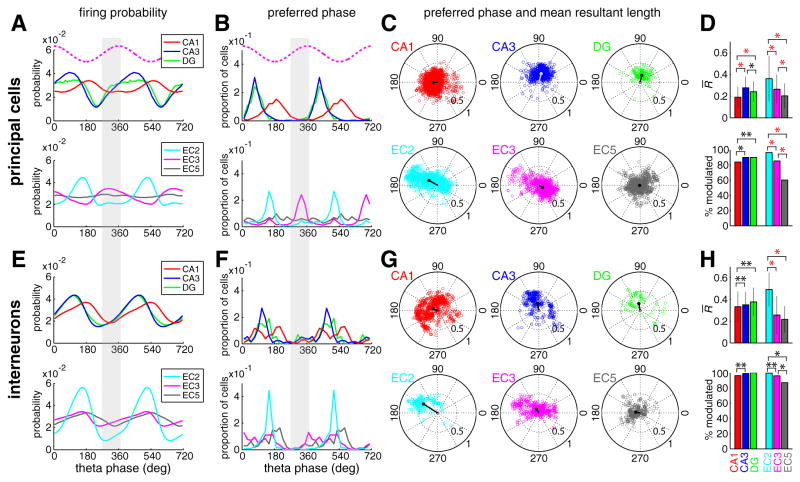

Figure 3. Theta phase modulation of hippocampal and EC neurons.

(A) Population discharge probability of principal neurons from different subregions as a function of EC3 theta phase (top dotted magenta traces in A and B, idealized reference theta cycle in EC3). Spikes from all principal neurons were included, independent of whether or not the neuron was significantly modulated by theta phase. Two theta cycles are shown to facilitate visual comparison. DG, dentate gyrus cells. Bin size = 10°. Note the deviation of most histograms from an idealized sinusoidal pattern. (B) Distribution of preferred phase of single neurons. Note that the majority of EC3 neurons occupy a phase space (ascending phase of EC3 theta), in which the discharge probability of all other neurons groups is at minimum (shaded columns in A, B, E and F). Bin size = 20°. (C) Polar plots of preferred phase and modulation depth (mean resultant length) of single neurons (circles) and group mean (lines). Only neurons with significant theta modulation (with at least 50 spikes and firing rate > 0.1 Hz; Rayleigh test, p<0.01) are included in (B) and (C). Note the largest mean resultant length in EC2 and in a small subset of EC3 principal cells with a phase preference opposite to the majority of the EC3 population. (D) Magnitude of modulation depth by the theta cycle (mean resultant rength ± standard deviation; only significantly theta-modulated neurons are included) and the percentage of neurons significantly modulated by the theta cycle. **; p < 0.05, *; p < 10−4, red *; p < 10−11, Wilcoxon rank sum test (mean resultant length) and chi-square independence test (proportion of significantly modulated cells). (E to H) Same display for interneurons.