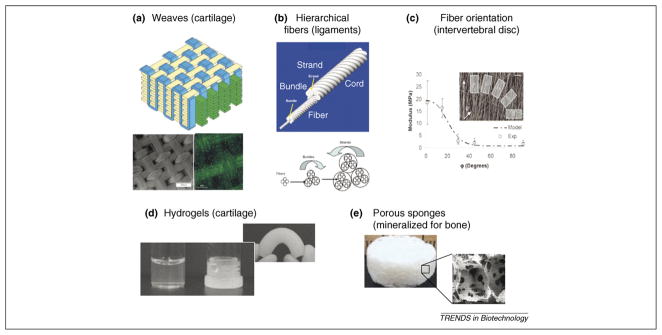

Figure 3.

Scaffold design: composite biomaterials for complex grafts. (a) Composite scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering made by microscale weaving of polycaprolactone fibers. Top: a schematic of the weave; bottom left: surface view of the weave by scanning electron microscopy (scale bar represents 500 μm); bottom right: fluorescence image of articular chondrocyte seeded weave within a 2% agarose gel, labeled with calcein-AM (scale bar represents 100 μm) (reproduced, with permission, from [32]). (b) Scaffolds for ligament and tendon engineering that were formed through the use of silk fibroin yarns in hierarchically organized forms of bundles, strands and cords. Top: a schematic of the yarn organization; bottom arrows show the twisting direction of the yarns at each level of organization (reproduced, with permission, from [43]). (c) Electrospun polycaprolactone fibres were used to generate scaffolds for engineering an intervertebral disc. Insert: this shows sections that were cut from mats of electrospun fibers to provide different fiber orientations within the sample for mechanical testing; graph: predictions of mechanical properties (modulus) versus experimental data from the samples of electropsun mats, where the modulus of the material was related to the fiber orientation. These relationships are important in terms of replicating the fiber orientations found in tissue structures, such as the intervertebral disc, to provide sufficient resistance to mechanical compression. (reproduced, with permission, from [33]). (d,e) Examples of key component parts for osteochondral systems. (d) Hydrogels for cartilage – the samples shown were generated from silk fibroin protein by controlling water content during self-assembly into gel states. (e) Porous sponges formed by porogen leaching from silk fibroin after solidification; these sponges are used for bone formation. This system can be pre-mineralized as needed to alter initial mechanical properties.