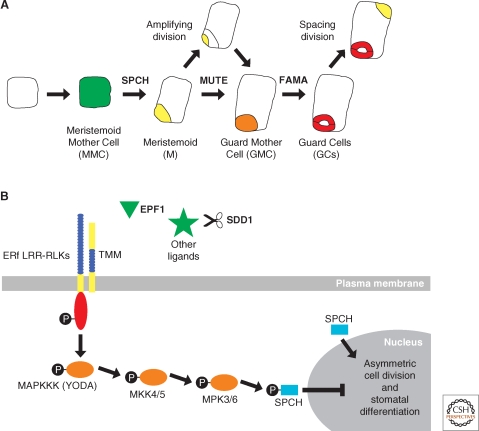

Figure 3.

Asymmetric cell division in stomatal development. (A) Schematic of a cell progressing through stomatal development. (A, from left to right) An undifferentiated leaf epidermal cell in Arabidopsis acquires Meristemoid Mother Cell fate (MMC, green) before undergoing an asymmetric cell division to produce a Meristemoid (M, yellow) and a larger sister cell (white). The M cell may then go through a series of asymmetric cell divisions, called amplifying divisions, before differentiating into a Guard Mother Cell (GMC, orange). The GMC divides symmetrically to produce a pair of Guard Cells (GCs, red) that together comprise a stomate. This process may reiterate when the larger sister cell divides asymmetrically in a spacing division to produce another M cell that is separated from existing stomata by one cell. The intrinsic factors SPCH, MUTE, and FAMA act sequentially to regulate asymmetric cell division and stomatal development. (B) Extrinsic factors and the signaling pathway proposed to negatively regulate stomatal development. First, a ligand binds to the leucine-rich repeats (LRR, blue) of a putative heterodimer complex between TMM and one of the ERf LRR-RLKs, which possess an intracellular kinase domain (red). This interaction is thought to initiate a cascade of phosphorylation events (black circles) involving downstream MAPK signaling proteins (orange), including YODA. Candidate ligands (green) acting to trigger this signaling cascade include small peptides such as EPF1 and putative unknown proteins that may be processed by SDD1. Biochemical evidence for this model is lacking, except for the final phosphorylation of SPCH by MPK3 and MPK6. SPCH phosphorylation ultimately results in repression of asymmetric cell division and stomatal differentiation. In contrast, when SPCH is unphosphorylated, it promotes asymmetric cell division and meristemoid fate, as shown in (A).