Abstract

Lasofoxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (estrogen agonist/antagonist) that has completed phase III trials to evaluate safety and efficacy for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and for the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. In postmenopausal women with low or normal bone mineral density (BMD), lasofoxifene increased BMD at the lumbar spine and hip and reduced bone turnover markers compared with placebo. In women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, lasofoxifene increased BMD, reduced bone turnover markers, reduced the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures, and decreased the risk of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. In postmenopausal women with low bone mass, lasofoxifene improved the signs and symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. Clinical trials show that lasofoxifene is generally well tolerated with mild to moderate adverse events that commonly resolve even with drug continuation. Lasofoxifene has been associated with an increase in the incidence of venous thromboembolic events, hot flushes, muscle spasm, and vaginal bleeding. It is approved for the treatment of postmenopausal women at increased risk for fracture in some countries and is in the regulatory review process in others.

Keywords: osteoporosis; SERM; fracture; efficacy; safety; BMD; CP-336,156

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) and poor bone quality that reduces bone strength and increases the risk of fractures.1 It is a major public health concern with serious clinical and economic consequences.2,3 Osteoporosis affects about 200 million people worldwide, including one-third of women between the ages of 60 and 70 years, and two-thirds of women aged 80 years and older,4 with 30% of women over the age of 50 years having one or more vertebral fractures.5 Fractures of the spine and hip are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.6,7 The direct health care cost in the United States (US) for fracture-related medical care was about US$17 billion in 20058 and over 36 million in Europe in 2000.9

Osteoporosis is diagnosed with BMD testing by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) according to criteria established by the World Health Organization10 (WHO) as adapted for use in clinical practice by the International Society for Clinical Densitometry11 (ISCD). Guidelines for the initiation of a pharmacological agent to reduce fracture risk are commonly based on estimation of fracture risk according to BMD T-score and/or clinical risk factors (CRFs) for fracture. Recent efforts to better identify patients at high risk for fracture have combined BMD with CRFs for fracture, which predicts fracture risk better than BMD or CRFs alone.3,12,13 The WHO fracture risk assessment algorithm14 (FRAX) uses validated CRFs and femoral neck BMD, if available, to estimate the 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, proximal humerus, and distal forearm) and the 10-year probability of hip fracture. Cost-effective country-specific intervention thresholds have been developed using FRAX with epidemiological data and numerous economic assumptions (eg, economic resources, health care priorities, societal willingness to pay).15,16 Patients who have the highest risk for fracture have the greatest fracture risk reduction with drug therapy.17,18 However, despite the availability of safe cost-effective drugs to reduce fracture risk, challenges remain. Osteoporosis continues to be underdiagnosed19,20 and undertreated,21,22 even in patients at very high risk of fracture.23,24 When treatment is prescribed, some patients do not fill the prescription and many do not take it correctly or long enough to benefit.25

Pharmacological agents proven to reduce fracture risk include estrogen with or without medroxyprogesterone,26,27 alendronate,28–30 risedronate,31–33 ibandronate,34 zoledronate,35,36 salmon calcitonin,37 strontium ranelate,38,39 raloxifene,40 bazedoxifene,41 lasofoxifene,42 teriparatide,43 and recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–84).44

Oral bisphosphonates (eg, alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate) are generally considered to be first line therapy for osteoporosis because of their proven efficacy in reducing fracture risk and good safety profile. However, oral dosing of bisphosphonates is complex (pre-dose fasting, ingestion with plain water only, post-dose fasting in upright position) and has been associated with gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in clinical practice patients.45 Intermittent intravenous (IV) bisphosphonates (eg, ibandronate, zoledronate) do not have GI intolerance concerns, but must be given by office staff trained in their administration or at an infusion center. The selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) drug class (eg, tamoxifen, clomiphene, raloxifene, bazedoxifene, arzoxifene, lasofoxifene) has been reclassified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as “estrogen agonist/antagonists.” These drugs, as with other antiresorptive agents, improve bone strength and reduce fracture risk by decreasing bone turnover, resulting in stabilization or an increase in BMD, preservation of bone microarchitecture, reduction in trabecular perforation, and a decrease in cortical porosity. The BMD increases that are observed with reduced bone turnover are due to filling in of the remodeling space and increased secondary mineralization.

The SERMs are a heterogeneous group of compounds that attach to the ligand-binding domain of estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ) through their stilbene-like cores. The resulting conformational changes at the ligand-binding domain may differ from estrogen depending on the physiochemical properties of the SERM. The estrogen-agonist or estrogen-antagonist effects of SERMs vary according to the expression of co-activators and/or co-repressors of gene activity in the target cell or tissue type. Tamoxifen is a SERM that inhibits the proliferation of breast cancer cells,46 but its use is limited due to undesirable effects on the endometrium.47 It is approved for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer. Another SERM, clomiphene, is approved for infertility treatment in premenopausal women. Raloxifene is approved for prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMO), reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, and prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women. It has desirable estrogen-like effects on the skeleton, with antiresorptive activity resulting in stabilization or improvement in BMD and reduction in the risk of vertebral fractures.40 It also has beneficial antiestrogen effects in breast tissue, where it has been shown to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer similar to tamoxifen.48 Undesirable effects include increased risk of thromboembolic events and hot flushes.40 An ideal SERM for the management of PMO would reduce bone remodeling, stabilize or increase BMD, and decrease fracture risk throughout the skeleton, while mitigating or eliminating menopausal symptoms (eg, hot flushes, vaginal dryness) and having neutral or beneficial effects on breast and endometrial cells, lipids, cardiovascular and thromboembolic disease, cognitive function, and urogenital function. Systematic screening of candidate compounds has been conducted to search for those with optimal therapeutic profiles. Some molecules (eg, droloxifene, levormeloxifene, idoxifene) that initially appeared promising subsequently failed due to adverse effects, primarily with the uterus.49 In a pivotal, five-year, phase III trial, arzoxifene was reported to decrease the risk of vertebral fractures and invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, but was dropped from clinical development due to failure to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in key secondary efficacy endpoints, such as nonvertebral fractures, clinical vertebral fractures, cardiovascular events, and cognitive function, compared to placebo.50 Bazedoxifene, which has been shown to reduce the risk of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis,41 is approved for use in the European Union (EU) and is under regulatory review in the US (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key efficacy and safety endpoints of lasofoxifene compared with bazedoxifene and raloxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis

| Efficacy | Safety | Regulatory Status | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lasofoxifene | Decreased risk of vertebral fractures and nonvertebral fractures; reduced risk of breast cancer; relieved symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy | Increased risk of VTE; increased risk of vaginal bleeding | Approved in EU |

| Bazedoxifene | Decreased risk of vertebral fractures | Increased risk of VTE | Approved in EU |

| Raloxifene | Decreased risk of vertebral fractures; reduced risk of breast cancer | Increased risk of VTE; increased risk of fatal stroke in postmenopausal women at high risk for coronary artery disease | Approved in US, EU, and other countries |

Abbreviations: EU, European Union; VTE, venous thromboembolic events; US, United States.

This is a review of the data evaluating lasofoxifene tartrate (CP-336,156, CP-336156, Fablyn, formerly Oporia, Pfizer Inc. and Ligand Pharmaceuticals) for use in the prevention and treatment of PMO.

Structure and mechanism of action

SERMs may be classified according to their core structure, which is typically a variation of the 17β-estradiol template, and sub-classified according to the side-chain at the helix 12 affector region.51 The triphenylethylenes have a stilbene core that mimics the nonsteroidal agonist diethylstilbestrol. Tamoxifen, a drug used in the management of breast cancer, is perhaps the best known of the triphenylethylenes; others include clomiphene, toremifene, droloxifene, miproxifene, and idoxifene. The clinical applications of this class of SERMs have often been limited due to adverse effects on the uterus. The benzothiophenes, such as raloxifene and arzoxifene, are associated with skeletal benefit while having little if any uterine stimulation. Indole-based SERMs (eg, zindoxifene, pipindoxifene, and bazedoxifene) have a 2-phenyl ring system that serves as a core binding unit.52 Other classes are the benzopyrans (eg, levormeloxifene) and the napthalenes (eg, nafoxidene, trioxifene, lasofoxifene).

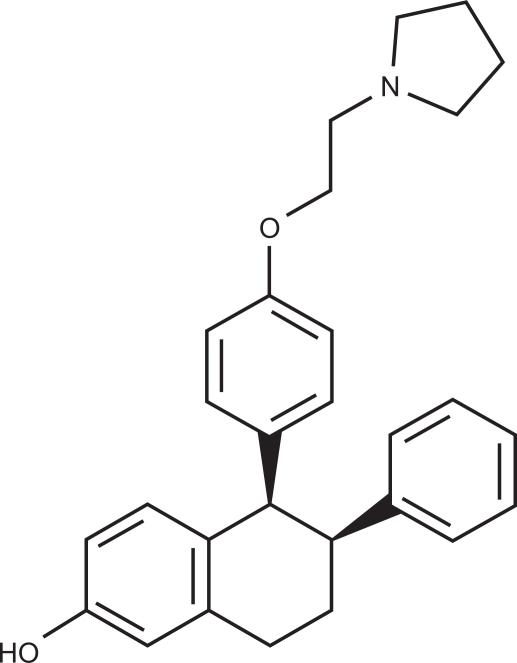

Lasofoxifene [(5R,6S)-5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-6-phenyl-5-(4-(2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)ethoxy)phenyl)-2-naphthalenol] (Figure 1) was developed through a systematic drug discovery program intended to find a nonsteroidal agent with properties of good oral bioavailability and the beneficial effects of estrogen.53 Structural classes known to interact with the estrogen receptor, including the benzothiophenes, were surveyed. Since there was evidence that extensive gastrointestinal (GI) glucuronidation of the 6- and 4′-hydroxyl groups of orally administered raloxifene was responsible for its limited systemic bioavailability and reduced potency compared with estrogen, the search was directed toward modifying the benzothiophene to reduce glucuronidation. Experiments ultimately resulted in the discovery of CP-336,156 (later called lasofoxifene), a SERM with excellent oral bioavailability due to minimal GI glucuronidation, and potency similar to estrogen at preventing bone loss and lowering total serum cholesterol in rats, without estrogen-like proliferative effects on breast and uterine tissue. This provided the basis for its clinical development as a potential agent in the management of PMO.

Figure 1.

Lasofoxifene.

Lasofoxifene has a high affinity for both ERα and ERβ, approximately the same as estradiol, and about 10-fold higher than SERMs such as raloxifene, tamoxifen, and droloxifene.54,55 Lasofoxifene is also highly selective, having more than a 100-fold selectivity against all other steroid receptors.53,56 The high bioavailability of lasofoxifene (about 60%) may contribute to the observed high potency (as assessed by alteration of estrogen-sensitive biomarkers) reported in early animal53 and human studies.57

Pharmacological properties

A 14-day, randomized, placebo-controlled, investigator blind, multiple dose study of the clinical pharmacology of lasofoxifene was conducted in 65 healthy postmenopausal women (age range 48–61 years).57 Lasofoxifene was administered under supervision after an overnight fast of at least eight hours as an oral solution, with a loading dose of five times the daily dose followed by daily doses of 0.01 mg, 0.03 mg, 0.1 mg, 0.3 mg, 1 mg, or placebo. A loading dose was used in order to shorten the time required to achieve steady-state plasma concentrations. Samples were collected for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic assessments. Peak plasma concentrations (Cmax) were reached in about 6.0 to 7.3 hours, compared with a shorter Cmax of 0.5 hours that has been reported with raloxifene.58 The mean half-life was 165 hours (∼six days) with a range of 96–222 hours and mean maximum plasma concentration ranging from 0.09 ng/mL to 6.43 ng/mL. This compares with a far shorter mean half-life of about 32.5 hours (range 15.9–86.6 hours) with raloxifene,59 but is similar to the reported half-lives of other SERMs, such as toremifene and tamoxifen.58 Administration of loading doses resulted in reaching steady-state concentrations within approximately seven to nine days. The pharmacokinetics of lasofoxifene are linear over a wide dose-range (0.01 to 100 mg)57 and are not significantly affected by age, ethnicity, weight, moderately impaired hepatic or renal function, or medications such as warfarin, ketoconazole, and digoxin.60–63 In a study of lasofoxifene disposition in healthy male subjects, it was eliminated by phase I oxidative metabolism (largely mediated by CYP2D6 and CYP3A4) and phase II conjugation.64

Preclinical studies

Lasofoxifene was identified as a SERM with potential clinical utility through a systematic drug discovery program for screening candidate compounds in three stages: 1) measurement of the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for estradiol binding to the estrogen receptor in the rat, 2) efficacy in the prevention of bone loss in ovariectomized (OVX) rats, and 3) antiproliferative effects in the estrogen sensitive MCF-7 breast cancer cell line.53 Particular attention was paid to oral bioavailability of these compounds, which was improved with greater resistance to intestinal wall glucuronidation. Lasofoxifene ultimately emerged as the SERM with the most favorable overall profile for pharmacokinetics and efficacy. An extensive preclinical program for further study of lasofoxifene was then initiated.

In five-month old OVX Sprague-Dawley rats, lasofoxifene prevented bone loss, inhibited bone turnover, and prevented OVX-induced increases in body weight and total cholesterol.56 In a study of immature (three weeks old) female Sprague–Dawley rats, lasofoxifene had no effect on uterine wet or dry weight, and in aged (17 months old) female rats no uterine hypertrophy was observed.56 In the aged female rats, there was a decrease in total serum cholesterol, a decrease in fat body mass, and no effect on lean body mass. Bone histomorphometry parameters with lasofoxifene-treated OVX rats were fully equivalent with what was observed in those treated with estradiol.56 In 10-month-old male Sprague–Dawley rats, 60 days of treatment with lasofoxifene prevented bone loss induced by aging and orchidectomy, reduced bone turnover, and decreased serum cholesterol, with no effect on the prostate.65 Long-term (60 days) of treatment with lasofoxifene in aged (15-month-old) male rats prevented age-related decreases in bone mass and bone strength by inhibiting bone turnover, with a decrease in serum cholesterol and no change in prostate weight.66 In a two-year study of OVX female cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis), lasofoxifene prevented OVX-induced loss of bone and rise in bone turnover,67 did not increase uterine weight or endometrial thickness, and did not change the histology of mammary, vaginal, or cervical tissue.68 Mild endometrial fibrosis and cystic changes were seen in the lasofoxifene-treated animals, while significant increases in uterine weight and endometrial hyperplasia were found in those treated with conjugated equine estrogen.

Efficacy in clinical studies

Sources of information on the clinical use of lasofoxifene were abstracts presented at scientific meetings, a few publications in peer reviewed scientific journals, and documents prepared for regulatory review.69,70

In a 14-day phase I study of variable doses of lasofoxifene in healthy postmenopausal women, lasofoxifene was associated with partial suppression of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.57 Urinary N-telopeptide (NTX) tended to decrease with an increase in the lasofoxifene dose, with the greatest decrease in NTX observed with the highest (0.3 mg and 1.0 mg/day) doses. There were no significant reported decreases in serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP) with 14 days of lasofoxifene treatment.

A two-year phase II randomized, double-blind, active treatment and placebo controlled clinical trial compared the effects of two doses of lasofoxifene (0.25 mg and 1.0 mg/day) with raloxifene 60 mg/day and placebo in 410 postmenopausal women with baseline lumbar spine Z-scores between +2.0 and −2.5.71 This range of BMD was selected in order to evaluate the response of lasofoxifene for both the prevention and treatment of PMO. The primary efficacy endpoint was the percentage change in lumbar spine (L1–L4) BMD at two years compared with baseline. Secondary endpoints included the percentage change in bone turnover markers at two years compared with baseline, and changes in serum markers of lipid metabolism, coagulation, and inflammation at various time points during the study. At two years there was a significant increase in lumbar spine BMD with both doses of lasofoxifene compared with baseline (1.8% and 2.2% for 0.25 mg and 1.0 mg/day, respectively, P ≤ 0.05), compared with raloxifene (1.9% and 2.3% for 0.25 mg and 1.0 mg/day, respectively, P ≤ 0.05), and compared to placebo (3.6%% and 3.9% for 0.25 mg and 1.0 mg/day, respectively, P ≤ 0.05). Both drugs were equally effective at increasing total hip BMD and both drugs reduced bone turnover marker levels, with the effects of lasofoxifene generally greater than raloxifene. There was a significant reduction in LDL cholesterol levels at two years with lasofoxifene (20.6% and 19.7% with 0.25 mg and 1.0 mg/day, respectively, P ≤ 0.05) compared with raloxifene (12.1% decrease) and placebo (3.2% decrease). Lasofoxifene resulted in significantly greater decreases in total serum cholesterol and apolipoprotein (Apo) B-100, and a significantly greater increase in Apo A-1, compared with raloxifene, while there were no significant changes in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol or triglycerides in any group. Both lasofoxifene and raloxifene reduced levels of fibrinogen and antithrombin III compared with placebo, with the reduction greater with lasofoxifene than with raloxifene.

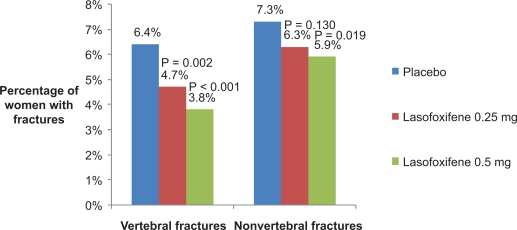

The Postmenopausal Evaluation And Risk-reduction with Lasofoxifene (PEARL) study was a five-year (with three-year analysis) randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (A2181002) evaluating the efficacy and safety of lasofoxifene in women with PMO.42,72 The primary outcome measures were new morphometric vertebral fractures at three years, new cases of ER+ breast cancer at five years, and new nonvertebral fractures at five years. Secondary outcome measures included, clinical vertebral and multiple vertebral fractures, all clinical fractures, nonvertebral fractures, hip fractures, BMD, breast cancer, cardiovascular events, and gynecological safety events at three years, and all clinical fractures, new morphometric vertebral fractures, BMD, cardiovascular events, and gynecological safety events at five years. A total of 8,556 women aged 59–80 years with lumbar spine or femoral neck T-score −2.5 or less was enrolled. Women with a baseline T-score < −4.5 at either skeletal site, or more than three morphometric vertebral fractures, or a vertebral fracture in the past year were excluded. Participants received calcium 1,000 mg and vitamin D 400–800 IU per day. Study subjects were randomized to receive lasofoxifene 0.25 mg or 0.5 mg/d or placebo. Compared with placebo, three years of lasofoxifene increased lumbar spine BMD by 3.3% (both doses, P < 0.001), and increased femoral neck BMD by 2.7% and 3.3% with 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d, respectively (P < 0.001). Over three years, lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d reduced the risk of vertebral fractures by 31% and 42%, respectively (P < 0.002), while nonvertebral fractures were significantly reduced by 22% with the 0.5 mg/d dose (P = 0.02) but not with the 0.25 mg/d dose (14% decrease, P = 0.13) (Figure 2). Both doses of lasofoxifene resulted in a significant reduction in bone turnover markers compared with placebo, with the median marker levels in the lower half of the premenopausal reference range.

Figure 2.

Three-year fracture risk in postmenopausal women treated with lasofoxifene.69 There was a statistically significant reduction in the risk of vertebral fractures with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d and a statistically significant reduction in the risk of nonvertebral fractures (defined as all fractures except fingers, toes, face, and skull) with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d.

PEARL was the only lasofoxifene study to evaluate breast cancer risk as an efficacy endpoint. It was found that both lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg significantly reduced the risk of ER+ breast cancer through three years (84% reduction with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 67% reduction with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg), with only lasofoxifene 0.5 mg significantly reducing the risk of ER+ breast cancer (by 81%) through five years compared with placebo. Both lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg significantly reduced the risk of ER+ invasive breast cancer through three years (82% reduction with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 73% reduction with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg). Lasofoxifene 0.5 mg significantly reduced the risk of ER+ invasive breast cancer by 83% through five years.

The Osteoporosis Prevention And Lipid lowering (OPAL) study consisted of two identical two-year double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trials (A2181003 and A2181004) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of three doses of lasofoxifene (0.025 mg, 0.25 mg, and 0.5 mg/d) or placebo. A total of 1,907 postmenopausal women aged 40–75 years with normal or low BMD (lumbar spine T-score ≤0.0 and ≥−2.5) were enrolled.73,74 The primary efficacy endpoints were change in lumbar spine (L1–L4) BMD by DXA from baseline at 24 months and in serum LDL cholesterol at six months. Secondary efficacy end points included hip BMD by DXA at six, 12, and 24 months, lumbar spine (L1–L4) BMD at six and 12 months, and change from baseline at six and 24 months in serum concentrations of bone turnover markers: resorption marker C-terminal telopeptide of type 1 collagen (CTX) and formation markers osteocalcin (OC) and procollagen type 1 N-terminal peptide (P1NP). Other endpoints included BMD at the hip and effects on extraskeletal tissue such as breast, vagina, brain, and cardiovascular system. All patients received 1000 mg calcium and 200 to 500 IU vitamin D daily. Pooled results from the 2 OPAL trials have been presented as abstracts.73,74 Lumbar spine BMD increases from baseline in all lasofoxifene-treated groups were statistically superior to placebo (P < 0.0001) at the first time point tested (six months) and were sustained throughout the 24-month study. Subjects in the 0.25 and 0.5 mg/d lasofoxifene groups experienced equivalent changes from baseline (2.3% increase for both doses at two years, P ≤ 0.001) in lumbar spine BMD, compared with a 0.7% decrease with placebo; these changes were statistically superior (P = 0.0002) to those experienced by the 0.025 mg/d group at six, 12, and 24 months. The pattern of hip BMD change was similar to lumbar spine BMD, with all groups receiving lasofoxifene superior to placebo (P < 0.001) at the earliest time point tested (six months) and remaining superior through 24 months. Subjects in the 0.25 and 0.5 mg/d lasofoxifene groups experienced similar changes from baseline in hip BMD; these changes were statistically superior (P ≤ 0.05) to those of the 0.025 mg/d group at six, 12, and 24 months. Lasofoxifene at all doses significantly (P < 0.001) decreased median serum levels of CTX relative to placebo at six months, indicating a reduced rate of bone resorption. Compared to placebo, serum CTX was 50% lower with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d and 51% lower with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d. At 24 months, median CTX levels were reduced from baseline in the 0.025 mg, 0.25 mg, and 0.5 mg/d dose groups by 0.0%, 12%, and 17%, respectively, compared with a 34% increase in placebo-treated subjects. The 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d lasofoxifene doses produced similar effects on CTX, and both doses were statistically superior (P = 0.001) in suppressing CTX compared with 0.025 mg/d. Lasofoxifene at all doses produced significant reductions in serum OC at six months, relative to placebo (P < 0.001). Compared to placebo, serum OC was 29% lower with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d. At 24 months, median OC levels decreased by 9%, 20%, and 17% for lasofoxifene, compared with an increase of 7% for placebo. The 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d lasofoxifene treatment groups produced similar changes in OC, and both doses were statistically superior (P ≤ 0.001) to 0.025 mg/d. Lasofoxifene at all doses significantly decreased median levels of P1NP relative to placebo at six months (P < 0.001). Compared to placebo, serum P1NP was 35% lower with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d. At 24 months, levels of P1NP were reduced by 22%, 33% and 33% in the 0.025 mg/d, 0.25 mg/d, and 0.5 mg/d lasofoxifene dose groups, respectively, compared to an increase of 3% in placebo-treated patients. P1NP reductions with lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d and 0.5 mg/d were similar. Changes in signs and self-assessed symptoms of vaginal atrophy, cognitive function, and lipids were periodically analyzed over 24 months. No increase in breast density or breast pain was reported in the lasofoxifene groups. Vaginal pH and the maturation index were improved at 12 and 24 months in all 3 lasofoxifene groups. At 24 months, lasofoxifene subjects had significantly lower percentages of parabasal cells and significantly higher percentages of immediate cells and superficial cells in the vagina versus PBO (P = 0.004). There was a significant improvement in vaginal pH at 12 and 24 months for all doses of lasofoxifene compared with placebo (P < 0.001). At 12 months, all lasofoxifene doses significantly decreased median LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol (TC), TC/HDL-cholesterol ratio, Apo B100, Apo B-100/Apo A1 ratio, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) and lipoprotein (a) versus placebo. There was a beneficial effect on Apo A1, a small decrease in HDL-cholesterol in one lasofoxifene group, and a 0.5 to 7.3% increase in median triglyceride levels. At 24 months, fibrinogen levels significantly decreased from baseline for all lasofoxifene groups compared with placebo.

A two-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated bone turnover marker changes in 51 postmenopausal women with osteopenia receiving either lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d or placebo.75 It was found that decreases in serum P1NP and urinary NTX at six months predicted an increase in lumbar spine and total hip BMD at one and two years, with almost all lasofoxifene-treated women (92% to 96%) having a significant decrease in serum-based bone turnover markers. This suggests that bone turnover markers may be useful in the early monitoring of patients treated with lasofoxifene and predictive of a subsequent BMD response.

Comparison of Raloxifene and Lasofoxifene (CORAL) was a two-year randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active treatment-controlled, parallel group phase III clinical trial (A2181030) in women aged 48–75 years who were least three years postmenopausal with a lumbar spine T-score ≥−2.5 and ≤0.0. Subjects were randomized to receive lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d, raloxifene 60 mg/d, or placebo. The primary endpoints were percentage change in lumbar spine BMD at 24 months compared with baseline and the percentage of BMD responders at 24 months. The results of CORAL have not been released.

Two pivotal, 12-week, phase III trials (A2181031 and A2181032) of identical design evaluated the efficacy of lasofoxifene 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg versus placebo in treatment of moderate to severe symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with low bone mass.69 There were four co-primary endpoints (measured as a change from baseline to week 12): subject self-assessed most bothersome moderate or severe baseline vulvovaginal symptom, vaginal pH, percentage of vaginal parabasal cells, and percentage of vaginal superficial cells. The findings were consistent with a beneficial effect of lasofoxifene on the signs and symptoms of postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy, and similar to what was reported in the PEARL study.

Safety and tolerability

Preclinical toxicology studies with lasofoxifene did not identify significant safety issues with regard to the intended use of lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women.69 In 23 clinical pharmacology studies in which most patients received a single dose of lasofoxifene, adverse events were mild, with no deaths or serious adverse events reported.69 A phase I study of lasofoxifene in healthy postmenopausal women reported a total of 62 adverse events in 23 of the 49 subjects treated with lasofoxifene, 31 of which were considered to be treatment-associated.57 The most frequently reported adverse events with lasofoxifene were headache, dizziness, nausea, hot flushes, and diarrhea. A total of eight adverse events was reported by five of 16 subjects receiving placebo, with the most frequently reported being headache and malaise. All of the adverse events associated with treatment were mild, and almost all adverse events resolved within 24 hours. There were no severe adverse events and no withdrawals due to adverse events reported during the study. Clinical laboratory abnormalities were generally transient and appeared unrelated to the study drug. The most common abnormalities, many of which were associated with abnormal baseline levels, included elevations in triglycerides, total cholesterol, and urine white blood cells.

Safety data from 17 phase II and III clinical trials, reported in a briefing document prepared for the FDA,69 included assessment of adverse events, serious adverse events, premature discontinuation, laboratory test abnormalities, vital signs, electrocardiogram parameters, and analyses of gynecological and cardiovascular safety. The adverse event profile was generally consistent with that seen for other SERMs. Reports from the phase II and III clinical program showed comparable rates of adverse events among treatment groups (89% in the placebo, 92% in the 0.25 mg, 92% in the lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d groups, and 92% for the pooled doses group, respectively), with most adverse events mild or moderate in intensity. The most commonly reported adverse events that appeared to be associated with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d treatment were hot flush, muscle spasms, and vaginal discharge. Hot flush was reported for 7% of patients who received placebo compared with 15% who received lasofoxifene 0.5 mg. Muscle spasms were reported for 8% of patients who received placebo compared with 16% of patients who received lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d. Vaginal discharge was reported for 3% of patients who received placebo compared to 6% of those who received lasofoxifene 0.5 mg, with significant improvement in symptoms of postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy in association with decreased vaginal pH, increased vaginal lubrication, and improved vaginal cell maturation index. Discontinuation of study treatment due to an adverse event occurred in 443 (9.4%), 515 (11.3%), 464 (10.8%), 1132 (11.0%) patients in the placebo, lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d, lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d, and pooled lasofoxifene treatment groups, respectively. The most frequent causes of discontinuation from lasofoxifene treatment were hot flushes, muscle spasm, and deep vein thrombosis. All causality serious adverse events were reported in 876 (18.6%), 962 (21.1%), 888 (20.6%), and 1926 (18.8%) patients in the placebo, lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d, lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d, and pooled lasofoxifene groups, respectively. Falls, cholelithiasis, osteoarthritis, cataracts, and pneumonia were the most common serious adverse events in patients treated with lasofoxifene or placebo; the incidence of these events was similar across treatment groups. There was a slightly increased all-cause mortality observed in the five-year PEARL data for those on lasofoxifene 0.25 mg/d (hazard ratio [HR] 1.38, P = 0.0489) compared with placebo, but no significant increase in mortality in the lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d group or the pooled data for both 0.25 and 0.5 mg/d. There was no dose response relationship with mortality and no pattern of causality; no plausible explanation has emerged to account for this observation, the clinical significance of which remains uncertain.

Safety endpoints of particular interest were identified by the FDA in the categories of venous thromboembolic events, stroke, other cardiovascular events, and gynecological adverse events.70 In the PEARL study, the preliminary five-year data showed a statistically significant increase in the risk of any venous thromboembolic event (HR 2.055, P = 0.011), deep vein thrombosis (HR 2.152, P = 0.020), and pulmonary embolism (HR 4.493, P = 0.035) with lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d compared with placebo, while there was no significant increase in the risk of retinal vein thrombosis, total strokes, or fatal strokes.70 When transient ischemic events were excluded, lasofoxifene treatment with 0.25 mg and 0.5 mg/d was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the risk of strokes through five years (HR 0.61, P = 0.031 and HR 0.64, P = 0.043, respectively). Lasofoxifene treatment was not associated with an increase in the risk of fatal or nonfatal major coronary events and did not appear to have a significant effect on blood pressure or heart rate. Lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d, but not 0.25 mg/d, was associated with a statistically significant decrease in major coronary events at five years (HR 0.68, P = 0.016). There was no significant increase in the risk of endometrial carcinoma in pooled data in 7,268 patients treated with lasofoxifene compared with 3,291 on placebo. Two cases of uterine sarcoma were reported in lasofoxifene-treated patients, with a possibility that both may have been pre-existing prior to exposure to lasofoxifene. There was no evidence of a clinically significant increase in the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia with lasofoxifene, and no increase in uterine leiomyomata, pelvic prolapse, or urinary incontinence. In two subgroup analyses in the PEARL study, an approximately twofold increase in the incidence of histologically confirmed endometrial polyps was observed. Endometrial polyps are associated with vaginal bleeding, but have a low risk for developing malignant features (less than 2%). In a PEARL endometrial substudy, 17.9% of patients receiving lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d were reported to have an increase in endometrial thickness (attributed to benign cystic atrophy, not hyperplasia) of at least 8 mm compared to none of the patients treated with placebo. The risk of vaginal bleeding was significantly increased in the pooled lasofoxifene groups in the PEARL study compared with placebo (HR 1.82, P = 0.0014), with the number of uterine-related procedures in lasofoxifene-treated patients who were not closely monitored about twofold greater than in those taking placebo.

Discussion

The SERM class of therapeutic agents occupies a unique niche in the management of PMO due to the broad range of nonskeletal as well as skeletal effects. While the ideal SERM (ie, one that enhances skeletal health while having neutral or beneficial effects on estrogen-sensitive nonskeletal tissue) has not yet been developed, lasofoxifene may provide an improved benefit-risk ratio compared with raloxifene. Its place amidst other drugs used to treat PMO, and its long-term (greater than five years) safety, are not yet known. It may have particular clinical utility in postmenopausal women who are at risk for nonvertebral fractures as well as vertebral fractures, especially those with symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy or high risk for breast cancer.

The evidence from lasofoxifene clinical trials suggests that the 0.5 mg daily dose is the most efficacious for the treatment of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. It was associated with a 42% reduction in the risk of new or worsening vertebral fractures and a 22% reduction in the risk of nonvertebral fractures through three years, with sustained fracture risk reduction through five years. It increased BMD at the lumbar spine and hip, and reduced markers of bone turnover. Lasofoxifene 0.5 mg/d also reduced the risk of ER+ breast cancer by 67% through three years and 81% through five years; reduced the risk of ER+ invasive breast cancer by 73% through three years and 83% through five years; and reduced the risk of all breast cancers by 65% through three years and 79% through five years compared with placebo, and reduces symptoms associated with vulvovaginal atrophy.

The five-year PEARL safety data evaluated 5,701 women who received lasofoxifene for a total exposure of 23,058 patient-years. Lasofoxifene was well tolerated, with a generally good safety profile and no evidence of increase risk of endometrial cancer. The overall incidence of adverse events, serious adverse events, and deaths was similar to placebo. As with estrogen and other SERMs, lasofoxifene increases the risk of venous thromboembolic events by about twofold. It did not increase risk of all strokes or fatal strokes and did not increase the risk of major coronary events. TC, LDL-cholesterol, and high sensitivity CRP levels were reduced at three years compared with placebo. Lasofoxifene did not increase the risk of endometrial cancer, endometrial hyperplasia, uterine prolapse, or urinary incontinence. Lasofoxifene was associated with an increase in endometrial thickness, benign endometrial polyps, and vaginal bleeding, requiring additional uterine procedures compared to placebo.

In August 2004, a new drug application (NDA) was filed with the FDA for lasofoxifene (as Oporia) 0.25 mg/d for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis (NDA 21–757), followed by an additional filing for the treatment of vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women with low bone mass (NDA 21–843) in December 2004. The FDA subsequently returned nonapprovable letters for both applications, recognizing that efficacy for both indications had been demonstrated, but citing concern with regard to a theoretical risk of endometrial cancer and an increased risk of invasive gynecological procedures. With the completion of PEARL, including the two-year extension of the original three-year trial, a new application for lasofoxifene (as Fablyn) 0.5 mg/d for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk of fracture (NDA 22–242) was submitted to the FDA. On September 8, 2008, the FDA Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs voted 9–3 (with one abstention) that there is a population of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis for whom the benefits of lasofoxifene likely outweigh the risks. The FDA has not yet issued a final ruling.

On March 24, 2009, the European Commission issued the first regulatory approval of lasofoxifene, as a 0.5 mg microfilm tablet marketed as Fablyn; it is indicated for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk of fracture and contraindicated for women with hypersensitivity to the drug of any of the excipients and those with a history of venous thromboembolic events, unexplained uterine bleeding, and women who are not postmenopausal. In the US, Fablyn remains under regulatory review.

If approved by the FDA, lasofoxifene will offer patients in the US a new option for the treatment of PMO that provides additional benefit over raloxifene, the only SERM that is currently approved for PMO in the US. Lasofoxifene should not be given to women with a history of thromboembolic events and should be used with caution, if at all, in women with disorders of the endometrium that increase the risk of uterine bleeding. Clinical experience with lasofoxifene in Europe is likely to provide a better understanding of its long-term benefits and risks.

Summary

Lasofoxifene is a SERM with proven efficacy in reducing the risk of vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis, reducing the risk of ER+ breast cancer, and relieving symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. It is well tolerated with a generally good safety profile. Lasofoxifene is a promising new agent that may provide added benefit beyond treatment options that are currently available.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Klibanski A, Adams-Campbell L, Bassford T, et al. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services . Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General 2004. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group . Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. Sheffield, UK: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, University of Sheffield; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Osteoporosis Foundation IOF Osteoporosis Teaching Slide Kit 2009. Available from: http://www.iofbonehealth.org/download/osteofound/filemanager/health_professionals/pdf/osteoporosis-teaching-slide-kit.pdf Accessed March 26, 2009.

- 5.Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54:58–63. doi: 10.1159/000063449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA. Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet. 1999;353:878–882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)09075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med. 1997;103:12S–19S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)90022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005–2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465–475. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanis JA, Johnell O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:229–238. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Study Group on Assessment of Fracture Risk and its Application to Screening for Postmenopausal Osteoporosis Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis Technical report series 843. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baim S, Binkley N, Bilezikian JP, et al. Official Positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and executive summary of the 2007 ISCD Position Development Conference. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:75–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Osteoporosis Foundation . Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Strom O, Borgstrom F, Oden A. Case finding for the management of osteoporosis with FRAX–assessment and intervention thresholds for the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1395–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization FRAX WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool 2008. Available from: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/ Accessed October 22, 2008.

- 15.Tosteson AN, Melton LJ, III, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Cost-effective osteoporosis treatment thresholds: the United States perspective. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:437–447. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0550-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ, III, et al. Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, et al. Ten-year fracture probability identifies women who will benefit from clodronate therapy–additional results from a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:811–817. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0786-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV. Bazedoxifene reduces vertebral and clinical fractures in postmenopausal women at high risk assessed with FRAX®. Bone. 2009;44(6):1049–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Osteoporosis is markedly underdiagnosed: a nationwide study from Denmark. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:134–141. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1680-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gehlbach SH, Fournier M, Bigelow C. Recognition of osteoporosis by primary care physicians. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:271–273. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Katz JN, Mogun H, Avorn J. Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Am J Med. 2003;115:398–400. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiebzak GM, Beinart GA, Perser K, Ambrose CG, Siff SJ, Heggeness MH. Undertreatment of osteoporosis in men with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2217–2222. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panneman MJ, Lips P, Sen SS, Herings RM. Undertreatment with anti-osteoporotic drugs after hospitalization for fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamel HK, Hussain MS, Tariq S, Perry HM, III, Morley JE. Failure to diagnose and treat osteoporosis in elderly patients hospitalized with hip fracture. Am J Med. 2000;109:326–328. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cramer JA, Gold DT, Silverman SL, Lewiecki EM. A systematic review of persistence and compliance with bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1023–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–1712. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Broll J, et al. Effect of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1437–1443. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511303332201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures – Results from the fracture intervention trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reginster JY, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. Vertebral Efficacy With Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–1352. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chesnut CH, III, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241–1249. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799–1809. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chesnut CH, III, Silverman S, Andriano K, et al. A randomized trial of nasal spray salmon calcitonin in postmenopausal women with established osteoporosis: the prevent recurrence of osteoporotic fractures study. PROOF Study Group. Am J Med. 2000;109:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00490-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reginster JY, Seeman E, De Vernejoul MC, et al. Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Treatment of Peripheral Osteoporosis (TROPOS) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2816–2822. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meunier PJ, Roux C, Seeman E, et al. The effects of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene – Results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;282:637–645. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silverman SL, Christiansen C, Genant HK, et al. Efficacy of bazedoxifene in reducing new vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from a 3-year, randomized, placebo-, and active-controlled clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1923–1934. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings SR, Eastell R, Ensrud K, et al. The effects of lasofoxifene on fractures and breast cancer: 3-year results from the PEARL trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:S81. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Greenspan SL, Bone HG, Ettinger MP, et al. Effect of recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1–84) on vertebral fracture and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:326–339. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ettinger B, Pressman A, Schein J. Clinic visits and hospital admissions for care of acid-related upper gastrointestinal disorders in women using alendronate for osteoporosis. Am J Man Care. 1998;4:1377–1382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powles TJ. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:730. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barakat RR. The effect of tamoxifen on the endometrium. Oncology (Williston Park) 1995;9:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Komm BS, Lyttle CR. Developing a SERM: stringent preclinical selection criteria leading to an acceptable candidate (WAY-140424) for clinical evaluation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;949:317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb04039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eli Lilly and Company Lilly reports on outcome of Phase III study of Arzoxifene 2009. Available from: http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=403905 Accessed September 7, 2009.

- 51.Miller CP. SERMs: evolutionary chemistry, revolutionary biology. Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8:2089–2111. doi: 10.2174/1381612023393404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gruber C, Gruber D. Bazedoxifene (Wyeth) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:1086–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosati RL, Da Silva JP, Cameron KO, et al. Discovery and preclinical pharmacology of a novel, potent, nonsteroidal estrogen receptor agonist/antagonist, CP-336156, a diaryltetrahydronaphthalene. J Med Chem. 1998;41:2928–2931. doi: 10.1021/jm980048b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eppenberger U, Wosikowski K, Kung W. Pharmacologic and biologic properties of droloxifene, a new antiestrogen. Am J Clin Oncol. 1991;14:S5–S14. doi: 10.1097/00000421-199112002-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bryant HU. Mechanism of action and preclinical profile of raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulation. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2001;2:129–138. doi: 10.1023/a:1010019410881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ke HZ, Paralkar VM, Grasser WA, et al. Effects of CP-336,156, a new, nonsteroidal estrogen agonist/antagonist, on bone, serum cholesterol, uterus and body composition in rat models. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2068–2076. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gardner M, Taylor A, Wei G, Calcagni A, Jr, Duncan B, Milton A. Clinical pharmacology of multiple doses of lasofoxifene in postmenopausal women. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:52–58. doi: 10.1177/0091270005283280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morello KC, Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. Pharmacokinetics of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:361–372. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snyder KR, Sparano N, Malinowski JM. Raloxifene hydrochloride. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:1669–1675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roman D, Bramson C, Ouellet D, Randinitis E, Gardner M. Effect of lasofoxifene on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin in healthy postmenopausal women. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1407–1412. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ouellet D, Bramson C, Carvajal-Gonzalez S. Effects of lasofoxifene on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of single-dose warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:741–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bramson C, Ouellet D, Roman D, Randinitis E, Gardner MJ. A single-dose pharmacokinetic study of lasofoxifene in healthy volunteers and subjects with mild and moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:29–36. doi: 10.1177/0091270005283278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ouellet D, Bramson C, Roman D, et al. Effects of three cytochrome P450 inhibitors, ketoconazole, fluconazole, and paroxetine, on the pharmacokinetics of lasofoxifene. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:59–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02709.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Prakash C, Johnson KA, Gardner MJ. Disposition of lasofoxifene, a next-generation selective estrogen receptor modulator, in healthy male subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1218–1226. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.020404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ke HZ, Qi H, Crawford DT, Chidsey-Frink KL, Simmons HA, Thompson DD. Lasofoxifene (CP-336,156), a selective estrogen receptor modulator, prevents bone loss induced by aging and orchidectomy in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1338–1344. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ke HZ, Qi H, Chidsey-Frink KL, Crawford DT, Thompson DD. Lasofoxifene (CP-336,156) protects against the age-related changes in bone mass, bone strength, and total serum cholesterol in intact aged male rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:765–773. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lees C, Shen V, Brommage R. Effects of lasofoxifene on bone in surgically postmenopausal cynomolgus monkeys. Menopause. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227858.50473.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cline JM, Botts S, Lees CJ, Brommage R. Effects of lasofoxifene on the uterus, vagina, and breast in ovariectomized cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:158. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfizer Inc FABLYN® (lasofoxifene tartrate) 0.5 mg Tablets, NDA 22–242, Reproductive Health Drugs Advisory Committee Briefing Document September82008. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4381b1-02-Pfizer.pdf Accessed August 9, 2009.

- 70.Division of Reproductive and Urological Products, Office of New Drugs, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration. Background Document for Meeting of Advisory Committee for Reproductive Health Drugs. NDA 22–242, Lasofoxifene Tartrate (Proposed trade name: FABLYN). September 8, 2008. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4381b1-01-FDA.pdf Accessed August 9, 2009.

- 71.McClung MR, Siris E, Cummings S, et al. Prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women treated with lasofoxifene compared with raloxifene. Menopause. 2006;13:377–386. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000188736.69617.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eastell R, Reid DM, Vukicevic S, et al. The effects of lasofoxifene on bone turnover markers: the PEARL trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:S81. [Google Scholar]

- 73.McClung M, Siris E, Cummings S, et al. Lasofoxifene increased BMD of the spine and hip and decreased bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with low or normal BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:S97. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davidson M, Moffett A, Welty F, et al. Extraskeletal effects of lasofoxifene on postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:S173. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rogers A, Glover SJ, Eastell R.A randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, trial to determine the individual response in bone turnover markers to lasofoxifene therapy Bone 2009August7[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]