Abstract

A method for the synthesis of peptidyl thioacids is described based on the use of the N-[9-(thiomethyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl]succinamic acid and cross-linked aminomethyl polystyrene resin. The method employs standard Boc chemistry SPPS techniques in conjunction with 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl protection of side chain alcohols and amines, and 9-fluorenylmethyl protection of side chains acids and thiols. Cleavage from the resin is accomplished with piperidine, which also serves to remove the side chain protection and avoids the HF conditions usually associated with the resin cleavage stage of Boc chemistry SPPS. The so-obtained thioacids are converted to simple thioesters in high yield by standard alkylation according to well-established methods.

Introduction

Thioacids [RC(=O)SH]1 are a fascinating but underappreciated class of compounds with a unique reactivity profile2 that arises in part from their pKa and the consequent ability of the conjugate base to act in a highly selective manner as nucleophile in aqueous media at pH3-6. Not surprisingly therefore most applications of thioacids have been in the field of peptide chemistry where they have been employed in amide bond forming reactions either directly3 or indirectly through their facile conversion to thioesters, key intermediates in a variety of chemical and enzymic amide ligation processes.4

The instability of thioesters toward the typical conditions of 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), particularly the treatment with organic bases employed in the cleavage of Fmoc groups, led to an initial reliance on tert-butyloxycarbonyl-based (Boc) chemistry for the synthesis of peptidyl thioesters,4o,q,5 but the HF conditions typically required for cleavage from the resin following Boc chemistry SPPS limit the use of this chemistry. Fmoc chemistry-based methods have subsequently been developed that replace piperidine in the Fmoc removal step by cocktails of 1-methylpyrrolidine, hexamethylenimine and 1-hydroxybenzotriazole but it has been found that these methods are prone to racemization at the thioester position.6 The backbone amide linker (BAL) strategy enables Fmoc chemistry SPPS with subsequent incorporation of a C-terminal thioester prior to cleavage from the resin but requires careful control of reaction conditions to avoid epimerization on introduction of the thioester to the C-terminal end of the peptide chain.7 To circumvent these problems numerous methods have been developed according to which, after completion of the peptide synthesis by Boc or Fmoc methods, the linker to the resin is activated in such a way as to permit its displacement by a thiol or thiolate resulting in the liberation of the peptide in the form of the desired thioester or thioacid.8 A variant on the BAL strategy, that avoids the epimerization problem, carries a C-terminal trithioorthoester through the Fmoc chemistry SPPS sequence before converting it to the required thioester by controlled hydrolysis.9 More recently, a number of strategies have been developed in which thioesters are generated by O-S or N-S shifts of mercapto esters and mercapto amides following unmasking of a protected thiol group.10 Despite the considerable ingenuity that has been deployed in the development of the above methods, none combine the directness that obviously results from the use of a simple C-terminal thioester-based linker with a method for release from the resin that avoids the use of HF. Previously we introduced the 9-fluorenylmethyl thioesters from which thioacids are liberated by simple treatment with piperidine, that is, under the conditions usually employed for the cleavage of Fmoc groups in Fmoc chemistry SPPS.11 We conceived that a linker based on the 9-fluorenylmethyl thioester would be compatible with the general conditions of Boc chemistry SPPS and that following peptide assembly treatment of the resin with piperidine would release the Boc-protected peptide into solution in the form of a C-terminal thioacid that could be readily transformed into a thioester by simple alkylation. Of essence, this method, whose reduction to practice we report here, employs conditions no more forcing than those encountered in standard Boc and Fmoc chemistry SPPS protocols and circumvents the terminal HF treatment that limits most Boc chemistry SPPS methods. We further conceived that the utility of such this method would be enhanced by the application of a side chain protection strategies involving either a third orthogonal system enabling retention of side chain protecting groups post cleavage,12 or a system according to which all protecting groups would be removed concomitantly with cleavage of the thioacid from the resin, depending on the ultimate application envisaged for the peptidyl thioacid.

Results and Discussion

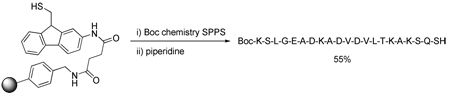

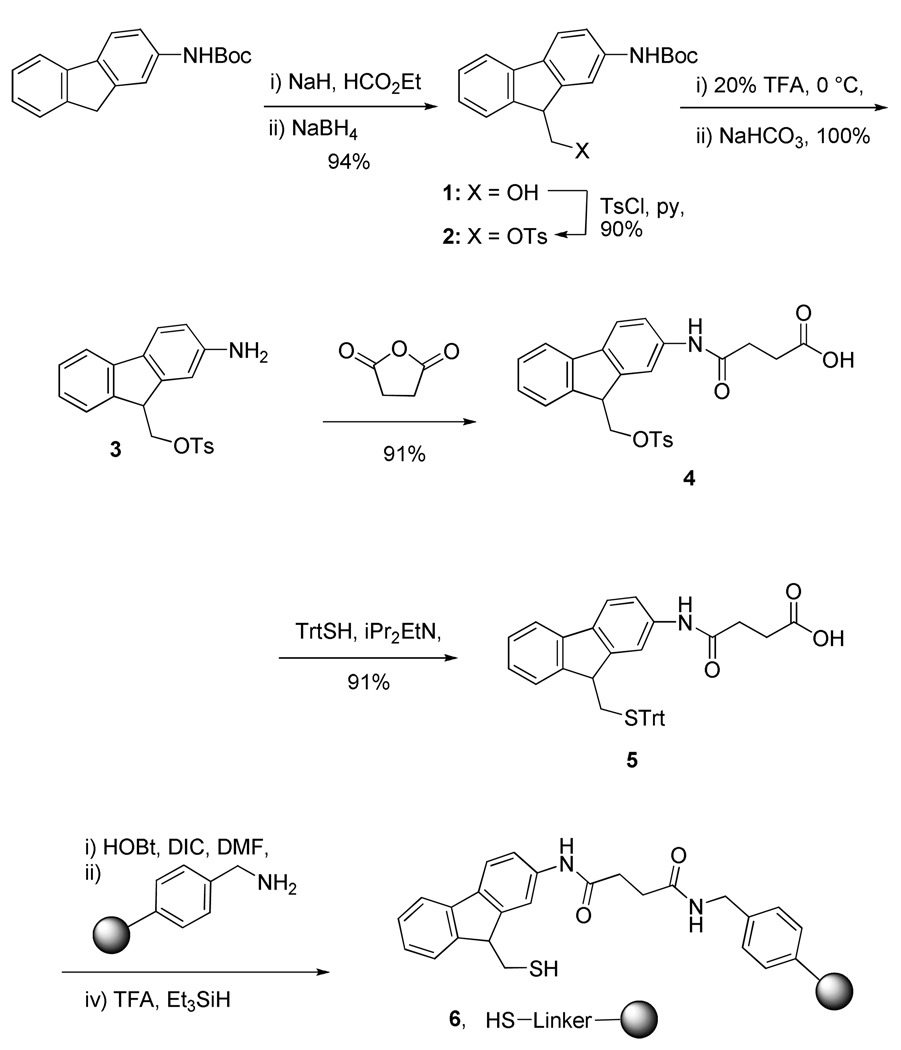

The mercapto functionalized linker, N-[9-(tritylthiomethyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl]succinamic acid (5) was prepared from commercially available 9H-fluoren-2-amine as shown in Scheme 1. The synthesis began with the conversion of 9H-fluoren-2-amine to corresponding hydroxyl functional compound 1 following a literature procedure13 involving formylation followed by reduction. Tosylation of 1 under standard conditions gave the sulfonate 2, from which the amine 3 was liberated with trifluoroacetic acid. Reaction of 3 with succinic anhydride provided the hemisuccinate 4 that was subjected to treatment with tritylmercaptan and Hunig’s base to give the protected linker 5 in excellent yield (Scheme 1). Treatment of 5 with diisopropyl carbodiimide and N-hydroxybenzotriazole in DMF gave an activated intermediate that was allowed to react with 1% divinylbenzene cross linked aminomethylpoystyrene resin (0.41 mmol/g loading). Following washing with DMF the functionalized resin was exposed to a 50% solution of TFA in dichloromethane to yield the desired resin-bound 9-fluorenylmethylthiol derivative 6 (Scheme 1). The attachment of linker 5 to the aminomethylpolystyrene resin was also accomplished in a satisfactory manner with the O-benzotriazolyl tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) reagent14 with the aid of diisopropylethylamine as base.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of a functionalized resin.

The preparation of a series of suitably protected amino acids was then undertaken. Thus, N-tert-butoxycarbonyl l-serine and the analogous l-threonine and l-tyrosine derivatives were converted to their allyl esters with potassium carbonate and then to the 9-fluorenylmethyl carbonates with Fmoc chloride and pyridine. A combination of palladium(II) acetate, triphenylphosphine and phenylsilane was the reagent of choice for the liberation the allyl esters required to complete this short sequence (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Preparation of protected hydroxyl amino acids

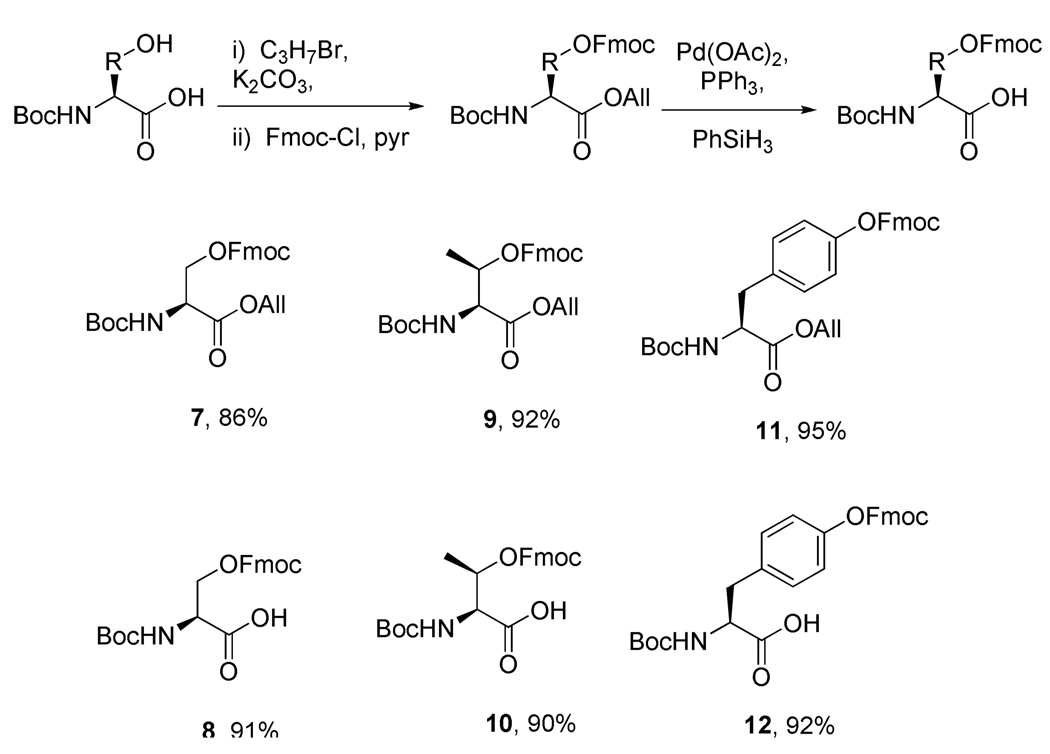

Following a literature protocol15 treatment of powdered l-aspartic and l-glutamic acids with triethylborane in THF at reflux for 24 h, then with 9-fluorenylmethanol, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and 4-dimethylaminopyridine, and finally with gaseous hydrogen chloride gave the mono esters 13 and 14. These HCl salts were then converted to the N-Boc derivatives in the standard manner (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Preparation of mono 9-fluorenylmethyl esters of aspartic and glutamic acid

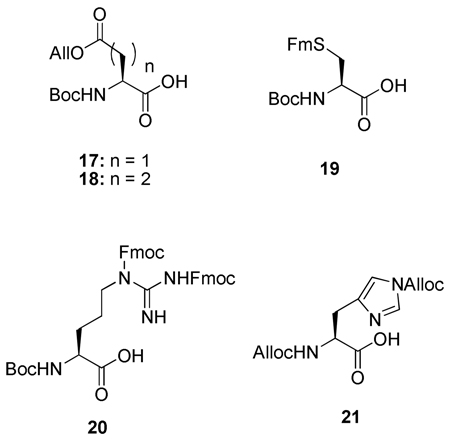

The corresponding mono allyl esters 17 and 18 were accessed according to the literature method16, as were the 9-fluorenylmethyl thioether of Boc-l-cysteine 19,15 the Fmoc-protected l-arginine derivative 20,17 and Alloc-protected l-histidine 21.18

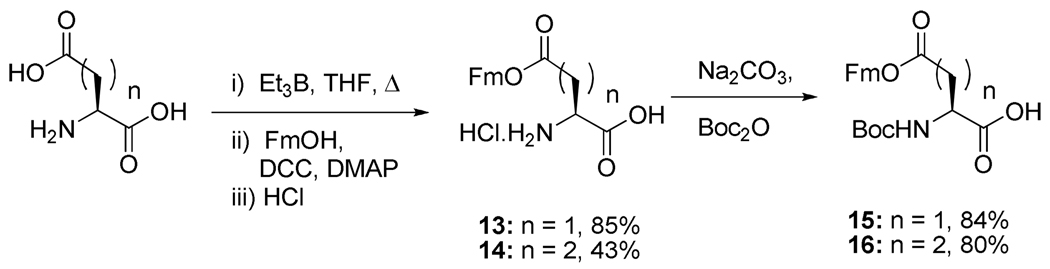

With all building blocks in hand attention was turned to SPPS using standard Boc techniques with DIC/HOBt as the coupling agent and TFA to liberate the N-terminus of the growing chains from their Boc derivatives. A number of peptides were assembled in this manner as set out in Table 1 (Entries 1–5). As with the preparation of the resin-bound thiol 6 (Scheme 1), this methodology is not limited to carbodiimide chemistry but is perfectly adaptable to the other methods as evidenced by the application of the HBTU protocol (Table 1, entry 6). After completion of the on-resin procedure, treatment with a solution of piperidine in DMF or, to enable direct loading of the reaction mixture to the HPLC column, acetonitrile released the desired thioacids protected at the N-terminal ends in the form of the Boc derivatives,19 which were typically obtained with a high degree of purity as determined by ESI-TOF and HPLC methods. Similar treatment of individual beads was used to systematically monitor the individual reaction steps during the course of the peptide assembly sequence. Although mass spectrometry was the method of choice for monitoring these SPPS reactions, the Kaiser ninhydrin test also performed in a perfectly satisfactory manner for both the coupling and Boc removal steps. While, the thioacid 22 was a simple model tetrapeptidyl thioacid (Table 1, entry 1), the peptidyl thioacids 23, 24, 25 and 27 are all natural sequences. The sequences of thioacids 23 and 24 (Table 1, entries 2 and 3) were selected from the Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)20 and represent segments 7–16 and 17–26, respectively, of that peptidyl hormone. Peptide 25 (Table 1, entry 4) represents the 94–101 segment of Human Secretory Phospholipase A2 (hsPLAA2),21 and peptide 27 (Table 1, entry 5) is the 65–84 unit of Human Parathyroid Hormone (hPTH).22

Table 1.

Boc chemistry SPPS of peptidyl thioacids.a

| Entry | Resin bound peptide | Peptide α-thioacid | % Yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boc-Met-Ala-Val-Ala-S-linker-

|

Boc-Met-Ala-Val-Ala-SH (22) | 95c |

| 2 | Alloc-His(Alloc)-Ala-Glu(OAll)-Gly- Thr(OFmoc)-Phe-Thr(OFmoc)- Ser(OFmoc)-Asp(OAll)-Val-S-linker-

|

Alloc-His-Ala-Glu(OAll)-Gly-Thr-Phe- Thr-Ser-Asp(OAll)-Val-SH (23) |

80c,d |

| 3 | Boc-Ser(OFmoc)-Ser(OFmoc)- Tyr(OFmoc)-Leu-Glu(OAll)-Gly-Gln-Ala- Ala-Lys(Alloc)-S-linker-

|

Boc-Ser-Ser-Tyr-Leu-Glu(OAll)-Gly- Gln-Ala-Ala-Lys(Alloc)-SH (24) |

78c |

| 4 | Boc-Ala-Ala-Thr(OFmoc)-Cys(Fm)-Phe- Ala-Arg(Fmoc)2-Asn-S-Linker-

|

Boc-Ala-Ala-Thr-Cys-Phe-Ala-Arg-Asn- SH (25) |

57e,f,g |

| 5 | Boc-Lys(Fmoc)-Ser(OFmoc)-Leu-Gly- Glu(OFm)-Ala-Asp(OFm)-Lys(Fmoc)-Ala- Asp(OFm)-Val-Asp(OFm)-Val8-Leu- Thr(OFmoc)-Lys(Fmoc)-Ala-Lys(Fmoc)- Ser(OFmoc)-Gln-S-Linker-

|

Boc-Lys-Ser-Leu-Gly-Glu-Ala-Asp-Lys- Ala-Asp-Val-Asp-Val8-Leu-Thr-Lys- Ala-Lys-Ser-Gln-SH (27) |

55e,h |

| 6 | Boc-Met-Ala-Val-Ala-S-linker-

|

Boc-Met-Ala-Val-Ala-SH(22) | 88c,i |

All reaction used ~0.1 mmol aminomethyl polystyrene resin (244 mg, resin loading 0.41 mmol/g). All cleavage steps used 25% TFA in CH2Cl2 (2 × 1.5 mL, 2 × 30 min.) after which the resin was washed with CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 mL), and neutralized with 5% DIPEA in CH2Cl2 (5 mL). All coupling reactions with the exception of entry 6i used Boc-l-amino acids (0.4 mmol) preactivated with HOBt (54 mg, 0.4 mmol) and DIC (62 µL, 0.4 mmol) in DMF (1 mL) for 30 min. The preactivated amino acid was added to the resin with an additional DMF (1 mL) and shaken for 3 h. After coupling the resin was washed with DMF (3 × 2 mL) and CH2Cl2 (3 × 2 mL).

With the exception of 22, which required no purification, yields are for compounds isolated and purified by RP-HPLC and are based on the substitution level of the aminomethyl polystyrene resin, taking into accountthe aliquots removed for monitoring of reaction progress.

The peptidyl thioacid was released from the resin by the treatment with 20% piperidine in DMF for 20 min.

The alloc group was cleaved from the side chain of the histidine residue in the course of the treatment with piperidine.

After incorporation of cysteine into the peptide sequence triethylsilane (0.5%) was included in the TFA/CH2Cl2 solution used for Boc-removal in all subsequent coupling steps.

The peptidyl thioacid was released from the resin by the treatment with 50% piperidine in acetonitrile for 30 min. Directly analogous results could be obtained with piperidine in DMF but the use of acetonitrile enables the reaction mixture to be loaded directly onto the HPLCfor purification.

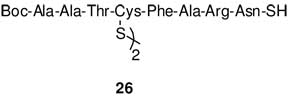

In addition to the desired peptide α-thioacid 25, 15% of a disulfide 26 corresponding to oxidative dimerization of thioacid was isolated by RP - HPLC. This structure is written as a symmetric cystine derivative rather than as the alternative diacyl sulfide as no such dimers were seen in any of the other examples.

After introduction of the 8th amino acid in the sequence and the removal of the Boc group it was found necessary to conduct the neutralization with a 5% solution of DIPEA in N-methylpyrrolidine. All subsequent coupling and deprotection steps in this sequence also employed N-methylpyrrolidine as solvent.23

This reaction sequence employed HBTU and iPr2NEt for the coupling reactions in place of DIC/HOBt.

The 1H and 13C-NMR spectra of the crude tetrapeptidyl thioacid 22 as obtained on simple release from the resin, acidification with HCl, and drying are presented in the supporting information (Figures 1 and 2) to illustrate the high degree of purity typically obtained by this method. In a similar vein the ESI-TOF mass spectrum of the peptidyl thioacid 27, immediately after release from the resin and prior to purification by HPLC is presented in the supporting information as Figure 3.

Particular attention is drawn to entries 4 and 5 of Table 1 in which the C-terminal amino acid is asparagine and glutamine, respectively. The amino acid building blocks for these residues were employed without protection of the side chain amide functionality and it is noteworthy that cyclization of these amides onto the resin-bound thioester with premature peptide release in the form of an imide did not occur to any significant extent.24 In general, the strategy of employing Fmoc protection for side chain amines and hydroxyl groups, coupled with the protection of side chain carboxylates and thiols ensures clean chemistry, while eliminating the need for extra deprotection steps pre- or post cleavage of the peptidyl thioacid from the resin. Nevertheless, should the retention of side chain protection be required on cleavage from the resin this may be conveniently accomplished through the use of building blocks whose side chains are covered with either the allyl or allyloxycarbonyl system12 depending on the case (Table 1, entries 2 and 3).

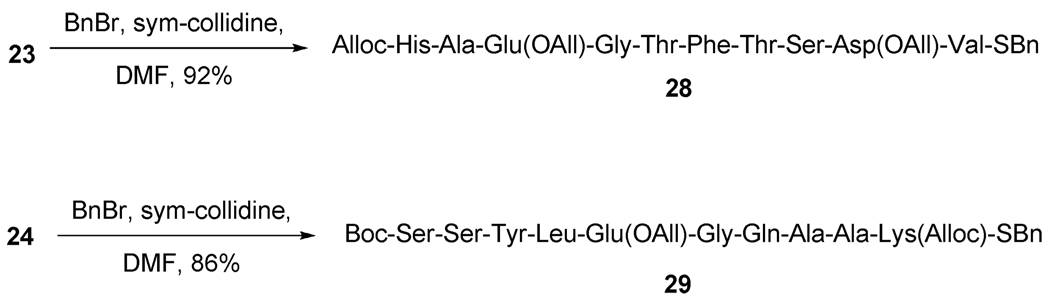

By way of example two of the peptidyl thioacids obtained in this manner were converted to the corresponding S-benzyl thioesters by simple alkylation with benzyl bromide and sym-collidine in DMF (Scheme 4).5c

Scheme 4.

Peptidyl thioester synthesis

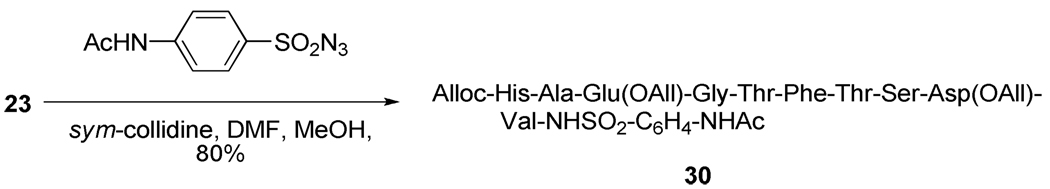

Finally, as a demonstration of the broad scope of the chemistry of thioacids, a single decapeptidyl thioacid was subjected to reaction with a sulfonyl azide, under conditions described by the Williams and Liskamp groups25 for much simpler substrates, resulting in the isolation of a C-terminal sulfonylamide (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Formation of a sulfonylamide.

Overall, we describe the successful implementation of a straightforward method for the SPPS of peptidyl thioacids using standard Boc chemistry with release from the resin using conditions typically used for Fmoc removal during the course of Fmoc chemistry SPPS. In conjunction with the protection of side chain amino and hydroxyl groups as Fmoc carbonates, and of side chain acids and thiols as 9-fluorenylmethyl esters and thioethers this chemistry provides a very convenient and mild means of access to peptidyl thioacids, and, by simple alkylation, of their S-esters.

Experimental

General

Unless otherwise stated 1H and 13C NMR were recorded in CDCl3 solution and optical rotations in CHCl3 solutions. All organic extracts were dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated under aspirator vacuum. Chromatographic purifications were carried out over silica gel. All peptide thioacid syntheses were carried out on a 0.1 mmol scale employing 1% DVB cross linked aminomethyl polystyrene resin (244 mg, resin loading 0.41 mmol/g) in a 10 mL manual synthesizer glass reaction vessel with a Teflon-lined screw cap. The peptide resin was shaken during the both Nα-tert-butoxycarbonyl deprotection and coupling steps. After each coupling step, formation of the desired peptide thioacid was confirmed by cleavage of a small amount (~ 5 mg) of resin using a 20% solution of piperidine in DMF for 20 min., followed by examination by ESI- TOF mass spectrometry. Isolated yields were determined based the theoretical yield calculated for the use of 0.1 mmol of resin with a loading of 0.41 mmol/g. These yields take no account of the aliquots removed for monitoring and are therefore minimum yields.

[2-(tert-Butoxycarbonylamino)-9H-fluoren-9-yl]methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (2)

To a stirred solution of [2-(tert-butoxycarbonylamino)-9H-fluoren-9-yl]methanol13 (1.8 g, 5.8 mmol) and 4-methylbenzenesulfonyl chloride (1.65 g, 8.7 mmol) in CHCl3 (20 mL) was added pyridine (0.9 mL, 11.6 mmol) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. Then the organic layer was washed with 1M HCl, water, brine, dried and concentrated. Chromatographic purification using 30% ethyl acetate in hexane afforded 2 (2.42 g, 90%). Yellowish syrup; 1H NMR (500 MHz) δ 7.78-7.76 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.66-7.61 (dd, J = 8.5, 12.8 Hz, 2H), 7.57 (s, 1H), 7.51-7.50 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.38-7.35 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.31-7.29 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.25-7.22 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 4.31-4.24 (m, 2H), 4.20-4.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (s, 3H), 1.56 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) δ 153.0, 145.1, 143.7, 142.5, 141.3, 138.0, 136.5, 133.0, 130.1, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 125.3, 120.7, 119.8, 118.8, 115.6, 80.9, 72.0, 46.9, 28.6, 21.8; ESI-HRMS Calcd for C26H27NO5S [M + Na]+ : 488.1508. Found: 488.1486.

(2-Amino-9H-fluoren-9-yl)methyl 4-methylbenzenesulfonate (3)

To a stirred solution of 2 (2.4 g, 5.2 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (16 mL), was added TFA (4 mL) dropwise at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at same temperature for 20 min before it was neutralized at 0 °C by saturated aqueous NaHCO3. Then the organic layer was washed with water, and brine, and dried and concentrated. Chromatographic purification using 40% ethyl acetate in hexane afforded 3 (1.9 g, 100%). Light yellow syrup; 1H NMR (400 MHz) δ 7.78-7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.57-7.55 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50-7.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.44-7.42 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.34-7.29 (m, 3H), 7.17-7.13 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (s, 1H), 6.71-6.68 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.26-4.18 (m, 2H), 4.13-4.09 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (br s, 2H), 2.41 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz) δ 146.4, 145.1, 144.7, 142.0, 141.7, 133.1, 132.3, 130.1, 128.2, 128.1, 125.7, 125.1, 121.1, 119.0, 115.2, 112.2, 72.5, 46.8, 21.9; ESI-HRMS Calcd for C21H19NO3S [M + H]+ : 366.1164. Found: 366.1152.

N-[9-(Tosyloxymethyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl]succinamic acid (4)

To a stirred solution of 3 (1.8 g, 4.9 mmol) in THF (10 mL) was added solid succinic anhydride (590 mg, 5.9 mmol) portion wise over a period of 10 min at room temperature. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then the reaction mixture was concentrated and subjected to chromatographic purification using 5% methanol in dichloromethane when it afforded 4 (2.1 g, 91%). White solid, crystallized from chloroform/hexane, mp: 165.8-166.2 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz) δ 7.65-7.63 (m, 3H), 7.55-7.51 (m, 3H), 7.37-7.7.36 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.26-7.2 (m, 4H), 7.14-7.11 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.20-4.13 (m, 2H), 4.07-4.04 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.67-2.62 (m, 4H), 2.32 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz) δ 175.6, 171.1, 145.3, 143.3, 142.4, 141.1, 137.7, 137.3, 132.5, 130.1, 128.2, 128.0, 126.8, 125.1, 120.5, 120.1, 120.0, 119.8, 116.8, 72.0, 46.8, 31.7, 29.4, 21.7; ESI-HRMS Calcd for C25H23NO6S [M + Na]+ : 488.1144. Found: 488.1120.

N-[9-(Tritylthiomethyl)-9H-fluoren-2-yl]succinamic acid (5)

To a stirred solution of 4 (2.0 g, 4.3 mmol) and triphenylmethanethiol (1.5 g, 5.4 mmol) in DMF (15 mL) was added diisopropylethylamine (1.8 mL, 10.8 mmol) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 15 h, after which the DMF was removed under high vacuum and the crude mixture was dissolved in EtOAc and washed with water, and brine, and dried and concentrated. Chromatographic purification of the residue using 4% methanol in dichloromethane afforded 5 (2.23 g, 91%). Light brown solid, crystallized from chloroform/hexane, mp: 84–85 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz) δ 7.80 (br s, 1H), 7.57-7.53 (m, 4H), 7.43-7.41 (m, 6H), 7.31-7.24 (m, 8H), 7.21-7.7.17 (m, 4H), 3.57-3.54 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.74-2.70 (m, 3H), 2.67-2.62 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) δ 177.5, 170.5, 147.2, 146.1, 144.9, 140.5, 137.5, 136.8, 130.0, 128.2, 127.7, 127.0, 126.7, 124.9, 120.4, 119.9, 119.7, 116.9, 67.6, 47.2, 36.1, 32.0, 29.7; ESI-HRMS Calcd for C37H31NO3S [M + Na]+ : 592.1922. Found: 592.1892.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the NIH (GM62160) for support of this work.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Complete experimental details, copies of the 1H and 13C-NMR spectra of compounds 2–5, 7–12, and 22–30, and HPLC traces and mass spectra of peptidyl thioacids 22–27.

References

- 1.a) Kato S, Kawahara Y, Kageyama H, Yamada R, Niyomura O, Murai T, Kanda T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:1262–1267. [Google Scholar]; b) Hadad CM, Rablen PR, Wiberg KB. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:8668–8681. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Bauer W, Kühlein K. In: Methoden der Organischen Chemie, 4th Ed; Carbonsäure und Carbonsäure Derivate. Falbe J, editor. Vol. 1. Stuttgart: Thieme; 1985. pp. 832–890. [Google Scholar]; b) Niyomura O, Kato S. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005;251:1–12. [Google Scholar]; c) Kato S, Murai T. In: The Chemistry of Acid Derivatives. Patai S, editor. Vol. 2. Chichester: Wiley; 1992. pp. 803–847. [Google Scholar]; d) Scheithauer S, Mayer R. Topics in Sulfur Chemistry. 1979;4:1–373. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Blake J. Int. Pept. Prot. Res. 1981;17:273–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1981.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamashiro D, Blake JF. Int. J. Pept. Prot. Chem. 1981;18:383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1981.tb02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Blake J, Yamashiro D, Ramasharma K, Li CH. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1986;28:468–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1986.tb03281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yamashiro D, Li CH. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1988;31:322–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1988.tb00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Mitin YV, Zapevalova NP. Int. J. Pept. Prot. Chem. 1990;35:352–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1990.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Høeg-Jensen T, Olsen CE, Holm A. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:1257–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Dawson PE, Muir TW, Clark-Lewis I, Kent SBH. Science. 1994;266:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.7973629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dawson PE, Kent SBH. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:923–960. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yeo DSY, Srinivasan R, Chen GYJ, Yao SQ. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:4664–4672. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Macmillan D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7668–7672. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hackenberger CPR, Schwarzer D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:10030–10074. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kent SBH. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:338–351. doi: 10.1039/b700141j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Flavell RR, Muir TW. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:107–116. doi: 10.1021/ar800129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Mihara H, Maeda S, Kurosaki R, Ueno S, Sakamoto S, Niidome T, Hojo H, Aimoto S, Aoyagi H. Chem. Lett. 1995:397–398. [Google Scholar]; i) Schnolzer M, Kent SB. Science. 1992;256:221–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1566069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Baca M, Kent SBH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:11638–11642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Williams MJ, Muir TW, Ginsberg MH, Kent SBH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:10797–10798. [Google Scholar]; l) Dawson PE, Kent SBH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:7263–7266. [Google Scholar]; m) Futaki S, Sogawa K, Maruyama J, Asahara T, Niwa M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:6237–6240. [Google Scholar]; n) Camarero JA, Pavel J, Muir TW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:347–349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980216)37:3<347::AID-ANIE347>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o) Zhang L, Tam JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2363–2370. [Google Scholar]; p) Shao Y, Lu W, Kent SBH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:3911–3914. [Google Scholar]; q) Tam JP, Lu Y-A, Liu C-F, Shao J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:12485–12489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Canne LE, Walker SM, Kent SBH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:1217–1220. [Google Scholar]; b) Canne LE, Ferre- D'Amare AR, Burley SK, Kent SBH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:2998–3007. [Google Scholar]; c) Lu W, Qasim MA, Kent SBH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8518–8523. [Google Scholar]; d) Hojo H, Aimoto S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1991;64:111–117. [Google Scholar]; e) Kawakami T, Kogure S, Aimoto S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1996;69:3331–3338. [Google Scholar]; f) Hojo H, Kwon Y, Kakuta Y, Tsuda S, Tanaka I, Hikichi K, Aimoto S. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1993;66:2700–2706. [Google Scholar]; g) Zhang L, Tam JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:3311–3320. [Google Scholar]; h) Li Y, Yu Y, Giulianotti M, Houghten RA. J. Comb. Chem. 2008;10:613–616. doi: 10.1021/cc800076b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Li X, Kawakami T, Aimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:8669–8672. [Google Scholar]; b) Hasegawa K, Sha YL, Bang JK, Kawakami T, Akaji K, Aimoto S. Lett. Pept. Sci. 2002;8:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Jensen KJ, Alsina J, Songster MF, Vagner J, Albericio F, Barany G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:5441–5452. [Google Scholar]; b) Alsina J, Yokum TS, Albericio F, Barany G. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8761–8769. doi: 10.1021/jo990629o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Alsina J, Yokum TS, Albericio F, Barany G. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:7277–7280. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Schwabacher AW, Maynard TL. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1269–1270. [Google Scholar]; b) Ingenito R, Bianchi E, Fattori D, Pessi A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11369–11374. [Google Scholar]; c) Shin Y, Winans KA, Backes BJ, Kent SBH, Ellman JA, Bertozzi CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11684–11689. [Google Scholar]; d) Sweing A, Hilvert D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:3395–3396. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3395::aid-anie3395>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Camarero JA, Hackel BJ, De Yoreo JJ, Mitchell AR. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:4145–4151. doi: 10.1021/jo040140h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Blanco-Canosa JB, Dawson PE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:6851–6855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Yamamoto N, Tanabe Y, Okamoto R, Dawson PE, Kajihara Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:501–510. doi: 10.1021/ja072543f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brask J, Albericio F, Jensen KJ. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2951–2953. doi: 10.1021/ol0351044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Botti P, Villain M, Manganiello S, Gaertner H. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4861–4864. doi: 10.1021/ol0481028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Warren JD, Miller JS, Keding SJ, Danishefsky SJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6576–6578. doi: 10.1021/ja0491836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) George EA, Novick RP, Muir TW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:4914–4924. doi: 10.1021/ja711126e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kawakami T, Aimoto S. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:3871–3877. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crich D, Sana K, Guo S. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4423–4426. doi: 10.1021/ol701583t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The use of allyl esters in alloxycarbamates as a protecting group system orthogonal with both Boc and Fmoc chemistries is widely established. Grieco P, Gitu PM, Hruby VJ. J. Peptide. Res. 2001;57:250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.2001.00816.x. Kates SA, Daniels SB, Albericio F. Anal. Biochem. 1993;212:303–310. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1334. Kates SA, Solé NA, Johnson CR, Hudson D, Barany G, Albericio F. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:1549–1552. Bloomberg GB, Askin D, Gargaro AR, Tanner MAJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4709–4712. Alternative possibilities include the nitrobenzenesulfonyl protecting group for amines. Kan T, Fukuyama T. Chem. Commun. 2004:353–359. doi: 10.1039/b311203a. Halpin DR, Lee JA, Warren SJ, Harbury PB. PLOS Biology. 2004;2:1031–1038.

- 13.Albericio F, Cruz M, Debethune L, Eritja R, Giralt E, Grandas A, Marchan V, Pastor JJ, Pedroso E, Rabanal F, Royo M. Synth. Commun. 2001;31:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Dourtoglou V, Ziegler JC, Gross B. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:1269–1272. [Google Scholar]; b) Knorr R, Trzeciak A, Bannwarth W, Gillessen D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:1927–1930. [Google Scholar]; c) Fields GB, Tian Z, Barany G. In: Synthetic Peptides: A User’s Guide. Grant GA, editor. New York: Freeman; 1992. pp. 77–183. [Google Scholar]; d) Schnoelzer M, Alewood P, Jones A, Alewood D, Kent SBH. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res. 1992;40:180–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1992.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albericio F, Nicolas E, Rizo J, Ruiz-Gayo M, Pedroso E, Giralt E. Synthesis. 1990:119–122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster KL, Maude AB, O’Donnell ME, Mehrotra AP, Gani D. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2001;1:1673–1695. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katzhendler J, Klauzner Y, Beylis I, Mizhiritskii M, Shpernat Y, Ashkenazi B, Fridland D. PCT Int. Appl. 076744. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dangles O, Guibe F, Balavoine G, Lavielle S, Marquet A. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4984–4993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The peptides were isolated in the form of their N-Boc derivatives simply owing to the use of Boc-protected building blocks. Use of Fmoc-protected builing blocks in the final coupling step will necessarily yield peptides with the N-terminus unprotected.

- 20.Lee S-H, Lee S, Youn YS, Na DH, Chae SY, Byun Y, Lee KC. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:377–382. doi: 10.1021/bc049735+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hackeng TM, Griffin JH, Dawson PE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:10068–10073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairwell T, Hospattankar AV, Ronan R, Brewer HB, Jr, Chang JK, Shimizu M, Zitzner L, Arnaud CD. Biochemistry. 1983;22:2691–2697. doi: 10.1021/bi00280a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields GB, Fields CG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113 4202–4207 and references therein cited. [Google Scholar]

- 24.This is evident simply from the yields of the isolated thioacids 25 and 27, which require average minimum coupling yields of >93% and >97%, respectively, for each coupling deprotection cycle. For comparable reasons premature peptide cleavage by diketopiperazine formation at the level of deprotection of the dipeptide and the migration of side chain protecting groups to N-terminal amines on neutralization do not appear to be major concerns, at least for the examples provided.

- 25.a) Shangguan N, Katukojvala S, Greenberg R, Williams LJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7754–7755. doi: 10.1021/ja0294919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Merkx R, Brouwer AR, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1125–1128. doi: 10.1021/ol0501119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barlett KN, Kolakowski RV, Katukojvala S, Williams LJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:823–826. doi: 10.1021/ol052671d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kolakowski RV, Shangguan N, Sauers RR, Williams LJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5695–5702. doi: 10.1021/ja057533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Merkx R, Van Haren MJ, Rijkers DTS, Liskamp RMJ. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:4574–4577. doi: 10.1021/jo0704513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.