Abstract

Objective

Despite concerns about exposure to violent media, there are few data on youth exposure to violent movies. In this study we examined such exposure among young US adolescents.

Methods

We used a random-digit-dial survey of 6522 US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years fielded in 2003. Using previously validated methods, we determined the percentage and number of US adolescents who had seen each of 534 recently released movies. We report results for the 40 that were rated R for violence by the Motion Picture Association of America, UK 18 by the British Board of Film Classification and coded for extreme violence by trained content coders.

Results

The 40 violent movies were seen by a median of 12.5% of an estimated 22 million US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years. The most popular violent movie, Scary Movie, was seen by >10 million (48.1%) children, 1 million of whom were 10 years of age. Watching extremely violent movies was associated with being male, older, nonwhite, having less-educated parents, and doing poorly in school. Black male adolescents were at particularly high risk for seeing these movies; for example Blade, Training Day, and Scary Movie were seen, respectively, by 37.4%, 27.3%, and 48.1% of the sample overall versus 82.0%, 81.0%, and 80.8% of black male adolescents. Violent movie exposure was also associated with measures of media parenting, with high-exposure adolescents being significantly more likely to have a television in their bedroom and to report that their parents allowed them to watch R-rated movies.

Conclusions

This study documents widespread exposure of young US adolescents to movies with extreme graphic violence from movies rated R for violence and raises important questions about the effectiveness of the current movie-rating system.

Keywords: media, violence, adolescents, movies

A growing body of scientific literature documents the negative effects of exposure to violent media on children, adolescents, and adults. This work has been performed with diverse methods and samples, and the researchers have examined a broad range of both short- and long-term outcomes, consistently finding that exposure to violent video games, television, films,1 and music has been linked to increased aggression and violence.2,3 Taken together, a clear picture has emerged that exposure to violent media increases the likelihood of aggressive thoughts, emotions, and behavior.4–6 In addition, recent work has begun to extend our understanding of the effects of exposure to violent media in several ways. Experimental work has demonstrated that video game violence can lead not only to changes in attitudes and behavior but also to physiological desensitization, such that after playing violent video games, participants were less aroused by watching scenes of actual violence.7 Moreover, brain-imaging studies have suggested that a child's brain does not distinguish between real acts of violence and viewing media violence, and also that the “impact of [television] violence viewing may extend in time beyond the simple act of viewing [television] violence.”8 Therefore, even if children, on a conscious level, report knowing the difference between entertainment violence and real violence, their brains respond as if they were being exposed to a real threat. In addition, exposure to media violence may affect the development of other risk cognitions such as alcohol and marijuana use.9 Thus, the effects of viewing media violence may extend beyond aggressive behavior.

The weight of the scientific evidence has led organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Psychological Association, and the American Psychiatric Association to sign a joint statement on the negative effects of exposing children to media violence, which stated that “at this time, well over 1000 studies…point overwhelmingly to a causal connection between media violence and aggressive behavior in some children.”10

Given widespread agreement about the harmful effects of exposure to violent media, it is important to better understand from where the exposure comes. Studies on media violence have tended to focus on television shows2 and video games.9 Although the National Television Violence Study reported that 91% of the movies on television contained violence,11 beyond anecdotal reports12 we can find little empirical work published on adolescent exposure to movies that are rated R (under 17 requires accompanying parent or guardian) for violence. One recently published study estimated exposure of early adolescents in northern New England to violent movies and found it to be widespread, with extremely violent movies being seen, on average, by 28% of the sample.13 In this article we test the generalizability of this finding by reporting estimates of the percentage and number of early adolescents in the United States with exposure to extreme violence. We also describe characteristics of adolescents who are most likely to watch these movies and classify the different forms of graphic violence commonly portrayed in these movies.

Methods

Student Sample

Between June and October 2003, we conducted a random-digit-dial telephone survey of US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years. Recruitment and survey methods have been published previously.14 Briefly, we identified a list-assisted randomly generated sample of 377 850 residential telephone numbers, purged nonresidential telephone numbers, screened 69 516 households to identify residential households with age-eligible children (N = 9849), and successfully enrolled 6522 age-eligible adolescents into the study (66% of those eligible). Enrollment required parent and adolescent consent, and the study protocol and survey questions were approved by the Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects.

The distributions of age, gender, household income, and census region in the unweighted sample were almost identical to percentages approximated in the 2000 US Census.14 The sample was weighted to produce response estimates that are representative of the population of US adolescents aged 10 to 14 years that had seen each movie. Weights were used in determining the percentage and number of US adolescents who had seen the movies.

Movie Sample Selection and Survey Administration

We selected the top 100 US box-office hits per year for each of the 5 years preceding the survey (1998–2002, N = 500) and 32 movies that earned at least $15 million in gross US box-office revenues during the first 4 months of 2003. The survey was programmed to randomly select 50 movie titles from the larger pool of 532 movies for each adolescent interview. Movie selection was stratified according to the Motion Picture Association of America rating so that the distribution of movies in each list reflected the distribution of the full sample of movies (19% G/PG, 41% PG-13, and 40% R). Respondents were asked whether they had ever seen each movie title on their unique list so that, on average, 613 (SD: 26.6) responded to each movie title. We also asked the entire adolescent sample whether they had seen 2 extremely violent movies, Hannibal and Blade II.

Selection of Extremely Violent Movies

We used 3 independent sources to select the sample of extremely violent movies. We first selected from our sample of top-grossing films those movies that were rated R for violence by the Motion Picture Association of America (n = 152). From these, we selected only those that were also rated UK 18, which indicates that the rating board in the United Kingdom considered those movies suitable only for adults aged ≥ 18 years (n = 40). In addition, all of the movies in our sample were coded in a content analysis for the overall level of violence by determining both overall frequency of violence (none, minimal, moderate, or frequent; κ = 0.83) and overall salience of the violence (no violence, not at all salient, minimally salient, moderately salient, or extremely salient; κ = 0.82). We selected only movies in which both the overall violence was “moderate” or “frequent” and the salience was rated as “extreme.” All 40 movies that met the both the US and UK ratings criteria also met these coding criteria; therefore, the final list included 40 extremely violent movies as determined by 3 independent sources.

Classification of Violent Content

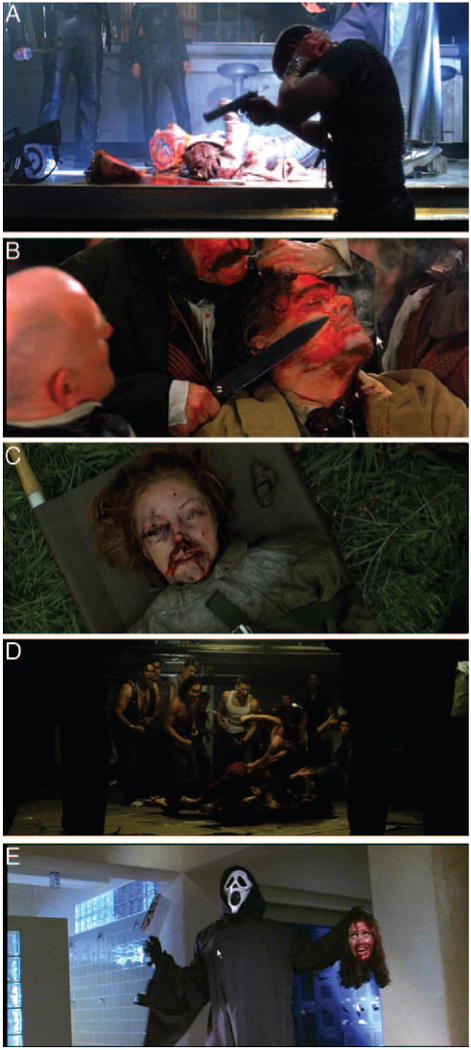

We classified the violence contained in these movies and illustrate the 5 types of violence commonly portrayed (Fig 1): horror with gore, sadistic violence, sexualized violence, extreme interpersonal violence, and comedic violence (for clips of these films, see Movies 1–5, which are published as supporting information at www.pediatrics.org/content/full/122/2/306). Figure 1A illustrates horror with gore. The still is from the movie Blade II, which was seen by 32.0% of the 10- to 14-year-olds surveyed and 23.3% of the 10-year-olds. In the clip (Movie 1), the vampire hunters execute 1 of their own members by shooting him, slicing off the top of his head, and exposing his brain. The vampire's body explodes into a bloody pool, with a final close shot of an eye blinking in the remains of the severed head.

FIGURE 1.

Five types of violence commonly portrayed in movies: A, horror with gore (Blade II); B, sadistic violence (Gangs of New York); C, sexualized violence (The General's Daughter); D, extreme interpersonal violence (Fight Club); E, comedic violence (Scary Movie).

Figure 1B illustrates sadistic violence; the violence takes place in the context of torture, human suffering, or extreme mental or physical pain. The still involves a character played by a popular movie star, Leonardo Di-Caprio, in the movie Gangs of New York, which was seen by 12.2% of the 10- to 14-year-olds surveyed and 2.9% of the 10-year-olds. In this scene (Movie 2), the crowd cheers as the character played by Daniel Day Lewis lays Leonardo DiCaprio's character out on a table, beats him with his fists and head, and finally brands his face with a hot knife blade to permanently scar and humiliate him.

Sexualized violence occurs in the context of a sexual act. The image in Fig 1C is from the movie The General's Daughter, which was seen by 8.7% of the adolescents in our sample, and 4.1% of the 10-year-olds. During a mock battle scene (see Movie 3), a female captain becomes disoriented and is repeatedly and graphically gang-raped by several camouflaged military men.

An example of extreme interpersonal violence is illustrated in Fig 1D, which is from the movie Fight Club (starring Brad Pitt), seen by 9.7% of our sample of 10- to 14-year-olds and 0.4% of the 10-year-olds. In this scene, an aggressively violent underground boxing match is taking place, in which Edward Norton's character relentlessly beats his opponent's face to a bloody pulp (see Movie 4).

The final image (Fig 1E) illustrates another form of violence shown in movies that are popular with adolescents: violence used for comedic purposes. Although intended to be funny, these scenes are often very graphic, and the violence is often an essential element of the humor and, indeed, the movie. Scary Movie demonstrates a high level of exposure to this type of violence: it had been seen by 48.1% of the 10- to 14-year-olds in our sample and 26.7% of the 10-year olds. In this scene (see Movie 5), “the killer” is mocked by a teen cheerleader, so he decapitates her and throws her head in a lost-and-found bin in the school locker room.

Validity

We evaluated the validity of adolescents' recognition of movie titles they had reported seeing 1 year previously and found that they correctly remembered having seen them ∼90% of the time.13,15 To assess the possibility of false-positive responses in this survey, we asked all adolescents whether they had seen a sham movie title, Handsome Jack, and fewer than 2% reported seeing it.

Statistical Analysis

Using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), we derived estimates for the proportion of adolescents watching movies by using the sampling weights and the Taylor series expansion method to estimate standard errors of estimators of proportions. To examine characteristics of adolescents who had watched the movies in the sample, we constructed a dichotomous variable that was equal to 1 if they had seen ≥ 1 of the 40 extremely violent movies and 0 if they had not seen any. The Rao-Scott χ2 test was used to examine the sampling-adjusted relationship between any violent movie watching and individual child and household characteristics. Maximum-likelihood multivariate logistic regression with sampling weights was used to estimate relationships between violent movie watching and child and household characteristics at the population level.

Results

Adolescent Exposure to Movies With Extreme Violence

Table 1 shows that every violent movie in the sample was seen by some 10- to 14-year-olds in the United States despite being rated R; in no case did the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for exposure overlap zero. The 2 most popular movies among 10- to 14-year-olds were Scary Movie, which was seen by 48.1% of adolescents, and I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, seen by 44.2%. The violent movies in the sample were seen by a median of 12.5% (interquartile range: 6.0%–23.4%) of 10- to 14-year-olds in the United States. Viewing rates among 10-year-olds, the youngest students in our sample, were generally lower than those for older adolescents; whereas the percentage of 10- to 14-year-olds who had seen each of the extremely violent movies in our sample ranged from 1.9 to 48.1%, the percentage of 10-year-olds who had seen each of these movies ranged from 0.4% to 26.7%. The most popular violent movies among 10-year-olds were Scary Movie (26.7%) and Hollow Man (24.0%).

TABLE 1. Adolescents Who Have Seen Extremely Violent Movies.

| Movie Title | Percentage (95% CI) of Adolescent Viewers Aged 10–14 y | Weighted No. (95% CI) of Adolescent Viewers Aged 10–14 y in the US, Millions | Percentage (95% CI) of Adolescent Viewers Aged 10 y | Weighted No. (95% CI) of Adolescent Viewers Aged 10 y in the US, Millions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scary Movie | 48.12 (43.41–52.83) | 10.05 (9.06–11.03) | 26.66 (15.62–37.7) | 1.15 (0.67–1.62) |

| I Still Know What You Did Last Summer | 44.15 (39.57–48.73) | 9.22 (8.26–10.17) | 23.32 (14.01–32.63) | 1.00 (0.60–1.40) |

| Blade | 37.39 (32.94–41.83) | 7.81 (6.88–8.73) | 23.48 (13.93–33.03) | 1.01 (0.60–1.42) |

| Bride of Chucky | 36.51 (32.03–41.00) | 7.62 (6.69–8.56) | 22.94 (14.5–31.38) | 0.99 (0.62–1.35) |

| Hollow Man | 32.05 (27.66–36.45) | 6.69 (5.77–7.61) | 24.03 (14.34–33.72) | 1.03 (0.62–1.45) |

| Blade II | 31.98 (30.64–33.33) | 6.68 (6.40–6.69) | 23.3 (20.39–26.2) | 1.00 (0.88–1.13) |

| Scream 3 | 31.98 (27.75–36.22) | 6.68 (5.79–7.56) | 23.13 (13.54–32.71) | 0.99 (0.58–1.41) |

| Training Day | 27.28 (23.22–31.33) | 5.70 (4.85–6.54) | 15.38 (7.29–23.46) | 0.66 (0.31–1.01) |

| Ghost Ship | 26.50 (22.49–30.52) | 5.53 (4.70–6.37) | 19.00 (10.85–27.16) | 0.82 (0.47–1.17) |

| Shaft | 23.83 (19.80–27.87) | 4.98 (4.13–5.82) | 10.77 (4.08–17.46) | 0.46 (0.18–0.75) |

| Hannibal | 22.96 (21.75–24.17) | 4.79 (4.54–5.05) | 8.10 (6.28–9.92) | 0.35 (0.27–0.43) |

| House on Haunted Hill | 22.20 (18.32–26.09) | 4.63 (3.82–5.45) | 12.36 (4.36–20.35) | 0.53 (0.19–0.88) |

| Kiss of the Dragon | 21.17 (17.28–25.05) | 4.42 (3.61–5.23) | 11.28 (4.52–18.05) | 0.49 (0.19–0.78) |

| All About the Benjamins | 18.89 (15.12–22.67) | 3.94 (3.16–4.73) | 15.97 (7.16–24.78) | 0.69 (0.31–1.07) |

| Halloween H2O: 20 Years Later | 18.29 (14.67–21.92) | 3.82 (3.06–4.58) | 11.59 (4.76–18.42) | 0.50 (0.20–0.79) |

| Urban Legend | 18.27 (14.86–21.68) | 3.81 (3.10–4.53) | 6.08 (1.43–10.73) | 0.26 (0.06–0.46) |

| Exit Wounds | 15.11 (11.34–18.88) | 3.15 (2.37–3.94) | 5.74 (0.40–11.07) | 0.25 (0.02–0.48) |

| The Players Club | 14.34 (10.27–18.41) | 2.99 (2.14–3.84) | 6.16 (0.43–11.89) | 0.26 (0.02–0.51) |

| Payback | 14.25 (10.44–18.06) | 2.98 (2.18–3.77) | 9.86 (2.58–17.13) | 0.42 (0.11–0.74) |

| The Cell | 12.83 (9.60–16.06) | 2.68 (2.00–3.35) | 7.18 (1.43–12.94) | 0.31 (0.06–0.56) |

| Gangs of New York | 12.24 (9.27–15.20) | 2.56 (1.94–3.17) | 2.93 (0.01–5.84) | 0.13 (0.00–0.25) |

| End of Days | 10.38 (7.24–13.53) | 2.17 (1.51–2.82) | 1.49 (0.00–4.40) | 0.06 (0.00–0.19) |

| Stigmata | 9.95 (7.27–12.64) | 2.08 (1.52–2.64) | 2.85 (0.02–5.67) | 0.12 (0.00–0.24) |

| Fight Club | 9.69 (7.29–12.08) | 2.02 (1.52–2.52) | 0.36 (0.00–1.08) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) |

| Soldier | 9.33 (6.78–11.88) | 1.95 (1.42–2.48) | 2.00 (0.00–4.57) | 0.09 (0.00–0.20) |

| The General's Daughter | 8.68 (6.10–11.25) | 1.81 (1.27–2.35) | 4.08 (0.00–8.26) | 0.18 (0.00–0.36) |

| John Carpenter's Vampires | 8.26 (5.67–10.86) | 1.72 (1.18–2.27) | 3.83 (0.63–7.03) | 0.16 (0.03–0.30) |

| The Art of War | 8.06 (5.63–10.48) | 1.68 (1.18–2.19) | 1.96 (0.00–4.25) | 0.08 (0.00–0.18) |

| Species II | 6.98 (4.60–9.37) | 1.46 (0.96–1.96) | 2.83 (0.30–5.36) | 0.12 (0.01–0.23) |

| From Hell | 6.47 (4.22–8.71) | 1.35 (0.88–1.82) | 3.47 (0.00–7.63) | 0.15 (0.00–0.33) |

| A Man Apart | 5.51 (3.34–7.68) | 1.15 (0.70–1.60) | 1.41 (0.00–3.38) | 0.06 (0.00–0.15) |

| Nurse Betty | 5.49 (3.19–7.79) | 1.15 (0.67–1.63) | 1.72 (0.00–4.11) | 0.07 (0.00–0.18) |

| The Big Hit | 4.91 (2.46–7.36) | 1.03 (0.51–1.54) | 4.47 (0.00–9.11) | 0.19 (0.00–0.39) |

| 8MM | 4.60 (2.44–6.76) | 0.96 (0.51–1.41) | 2.71 (0.00–5.88) | 0.12 (0.00–0.25) |

| 15 Minutes | 4.41 (2.54–6.27) | 0.92 (0.53–1.31) | 6.07 (1.12–11.02) | 0.26 (0.05–0.47) |

| Snatch | 4.33 (1.84–6.83) | 0.90 (0.38–1.43) | 0.49 (0.00–1.46) | 0.02 (0.00–0.06) |

| Summer of Sam | 3.45 (1.74–5.17) | 0.72 (0.36–1.08) | 0.72 (0.00–2.13) | 0.03 (0.00–0.09) |

| Go | 3.39 (1.84–4.94) | 0.71 (0.38–1.03) | 1.70 (0.00–3.81) | 0.07 (0.00–0.16) |

| Replacement Killers | 2.90 (1.49–4.31) | 0.61 (0.31–0.90) | 1.01 (0.00–2.43) | 0.04 (0.00–0.10) |

| The Corruptor | 1.93 (0.59–3.28) | 0.40 (0.12–0.68) | 2.82 (0.00–6.25) | 0.12 (0.00–0.27) |

Who Sees Extremely Violent Movies?

Table 2 illustrates the characteristics of adolescents who watched these movies and characteristics of their media environments. Controlling for the total number of movies seen, exposure to extremely violent movies was associated with older age, male gender, nonwhite race or ethnicity, lower parental education, and lower school performance (all P < .001). Exposure among black adolescents was especially high. Compared with white adolescents, black adolescents were 5.5 (95% CI: 4.2–7.0) times more likely to have seen ≥1 of the extremely violent movies. The most popular violent movies among black adolescents were Scary Movie (seen by 78.8%), I Still Know What You Did Last Summer (seen by 69.5%), and Blade (seen by 68.0%). Several other movies were seen by more than half of the black adolescents, including Training Day (65.6%), Bride of Chucky (65.2%), Hollow Man (60.3%), and Blade II (56.1%). Rates of viewing were especially high among black male adolescents, with the most popular movies for this group, Blade (82.0%), Training Day (81.0%), and Scary Movie (80.8%), seen by >80%. We tested a race-by-gender interaction, which was not significant; thus, these high levels of viewing reflect the additive effect of 2 strong main effects.

TABLE 2. Multivariate Logistic Regression Model Results for Seeing Any of the 40 Violent Movies (Using Survey Weights) (N = 6457).

| Predictor | Unweighted No. of Adolescents Asked | Weighted Percent of Adolescents Seeing ≥1 Violent Movie | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child age | |||

| 10 y | 1186 | 34.98 | Reference |

| 11 y | 1303 | 42.47 | 1.06 (0.83–1.37) |

| 12 y | 1338 | 50.57 | 1.05 (0.82–1.35) |

| 13 y | 1418 | 57.86 | 1.04 (0.81–1.34) |

| 14 y | 1277 | 71.54 | 1.56 (1.19–2.04) |

| Child gender | |||

| Female | 3172 | 42.98 | Reference |

| Male | 3349 | 58.93 | 1.93 (1.66–2.25) |

| Child race | |||

| White | 4037 | 42.02 | Reference |

| Hispanic | 1222 | 59.53 | 1.72 (1.38–2.13) |

| Black | 704 | 78.33 | 5.59 (4.25–7.35) |

| Other | 559 | 54.10 | 1.77 (1.35–2.33) |

| Parent education | |||

| Bachelors, graduate, or professional degree | 1987 | 35.11 | Reference |

| Some college, vocational/technical, or Associates degree | 1904 | 53.53 | 1.81 (1.48–2.21) |

| High school graduate or less | 2615 | 61.81 | 2.86 (2.34–3.49) |

| School performance | |||

| Excellent | 1979 | 39.61 | Reference |

| Good | 2725 | 50.56 | 1.04 (0.86–1.25) |

| Average | 1621 | 63.84 | 1.43 (1.16–1.77) |

| Below average | 181 | 76.93 | 2.48 (1.46–4.20) |

| Child has television in bedroom | |||

| No | 2578 | 38.07 | Reference |

| Yes | 3940 | 60.27 | 1.25 (1.06–1.47) |

| Parents allow R-rated movies | |||

| Never | 1989 | 22.64 | Reference |

| Once in a while | 2239 | 53.68 | 2.21 (1.81–2.70) |

| Sometimes | 1619 | 70.90 | 3.33 (2.68–4.13) |

| All the time | 646 | 87.44 | 7.06 (4.98–10.01) |

| Total movies seen | |||

| First quartile | 1729 | 13.97 | Reference |

| Second quartile | 1832 | 39.89 | 3.74 (3.00–4.66) |

| Third quartile | 1404 | 66.59 | 9.69 (7.61–12.33) |

| Fourth quartile | 1557 | 90.69 | 38.43 (28.87–51.16) |

Watching violent movies was also significantly associated with measures of media parenting. Adolescents who watched violent movies were more likely to have a television in their bedroom (adjusted odd ratio: 1.5) and to report that their parents allowed them to watch R-rated movies (adjusted odds ratio: 16.7 for an adolescent allowed to watch them all the time compared with those who said that they were never allowed).

Discussion

Our study documents the high exposure among young adolescents to extremely violent movies, some of which are seen by almost half of the 10- to 14-year-olds in the United States (eg, 10 million 10- to 14-year-olds had seen Scary Movie). This exposure occurs despite clear labeling that these movies were not intended for young adolescents, and these movies were intentionally chosen to represent the most violent of the popular movies released in the United States by requiring consensus across censor boards (R for violence in the United States and UK 18 in the United Kingdom). The body of research documenting a link between exposure to media violence and increases in violent thoughts, emotions, and behavior3,6,16 and even, perhaps, to increases in permissive attitudes toward other risk behaviors9 offers a compelling reason to restrict such exposure.

We not only found a high rate of exposure overall but also identified several independent risk factors for exposure. Boys, minorities, those with low socioeconomic status, and those with poor school performance are all more likely to see extremely violent movies. There is a strong relation between exposure and race, with black adolescents at particularly high risk for exposure. This is consistent with previous work that demonstrated a higher exposure to movies, television, and radio among black adolescents than among white adolescents.17 However, these effects held even when controlling for the total number of movies seen and, therefore, does not simply reflect risk factors for watching movies in general. Although more research needs to be performed to investigate the causes and consequences of these high rates of exposure to violent movies, given that many of these risk factors for exposure mirror risk factors for violent behavior (eg, race and gender),18 it is important to examine the role that movie exposure plays in encouraging violence in youth.

Although all mechanisms of the connection between exposure and behavior are not yet understood, it is clear that parents of adolescents should be aware of the negative consequences of this exposure and encouraged to limit it. However, many aspects of the modern media environment work against adequate parental oversight. With the advent of DVDs, movie channels, pay-per-view channels, and even Web-based movie downloads, adolescents have unprecedented access to adult media. Director's cuts on DVDs are not subjected to the ratings process and often include additional violent material that was edited out of the theatrically released version. These movies are often viewed in American homes, in which approximately two thirds of adolescents have a television and more than half have a VCR or DVD player in their bedroom,19 which makes parental oversight difficult. In addition, extremely violent films are marketed on television during programming that is seen by children and adolescents, which raises awareness of these films and piques interest.20 Even among adolescents who report that their parents never let them watch R-rated movies, 22.6% reported having seen at least 1 of these movies from their list.

These features of the media environment represent a significant challenge to parents who are interested in restricting their adolescents' exposure. Furthermore, parents may not be aware of the extremely graphic nature of these films and the high rates of exposure among young adolescents. Parents are often shocked when presented with the violent scenes included with this article, because many older adults (including pediatricians) do not watch them. For educational reasons, we have included with this article scenes from some of the movies that young adolescents watch (Movies 1–5); we believe that viewing the scenes may motivate pediatricians and parents to take movie violence more seriously. Parents may also not be aware of the well-documented connection between exposure to violence and negative outcomes such as increased aggression. Therefore, restriction to media violence may not be a top priority for some parents. It is not known to what extent parents are unaware of the violent content in some of these movies and to what extent they may discount the potential negative effects of them (eg, comedic violence). We urge pediatricians to play a more prominent role in motivating and educating parents to manage the home media environment, which may involve (1) educating parents about the high rates of exposure and the link between exposure and outcomes, (2) motivating parents to restrict access to violent media, and (3) conducting research into ways to assist parents in using available technology such as the V-Chip. In addition, these high rates of exposure to movies rated R for violence call into question the effectiveness of the current rating system. An R rating for violence tells parents that adolescents under the age of 17 must be accompanied by a guardian but does not clearly communicate that some of this violence should not be seen by young adolescents. Cross-cultural research should be performed to determine if more restrictive ratings systems, such as those of Canada and the United Kingdom (which prohibit children from seeing such movies in theaters), are more effective at preventing exposure.

One limitation of this study is that we assessed only whether adolescents had watched each of the movies, not how many times they watched them. In addition, when determining our movie sample, we selected only the most extreme examples of graphic violence. As a result, we suspect that we are underestimating their exposure to violence in movies. We chose this sample to determine if young adolescents are being exposed to movies about which there is considerable agreement that they should not see. Therefore, we captured exposure to movies that illustrate extreme examples of media violence. We do not argue that these are the only violent movies that may have a harmful effect on adolescents.

This raises another limitation: we assessed only exposure to movie violence, not the effects of such exposure. A compelling body of research has documented the relation between media exposure and aggression; however, much of this research has examined the effects of television programming and video games. Studies on the effects of movie violence have focused on young adults, and this represents a gap in our understanding of the role that violent media plays on early adolescent behavior, which should not be overlooked. Future work should examine more directly the link between exposure to movie violence and aggression among younger adolescents.

Conclusions

Young US adolescents are frequently exposed to movies with extreme graphic violence from movies rated R for violence. This widespread exposure raises important questions about the effectiveness of the current movie-rating system. In addition, it suggests that pediatricians ought to play a bigger role in motivating and teaching parents to impose restrictions on their use to reduce exposure, because many parents may not be aware of the violent level of content of these movies and the high level of exposure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants CA-77026 and AA-015591 and the American Legacy Foundation.

We thank Heather Olson and Michelle Glazer for assistance with the literature review and editorial assistance and Elaina Bergamini for supervising the content analysis.

Abbreviation

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

What's Known on This Subject: Exposure to violent media such as television and video games is linked to increased aggression and violence in children and adolescents.

What This Study Adds: We assessed exposure to extremely violent movies in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents and identified several risk factors for high exposure. Given the negative effects of exposure to violent media, it is important to assess exposure to violent movies.

References

- 1.Leyens JP, Camino L, Parke RD, Berkowitz L. Effects of movie violence on aggression in a field setting as a function of group dominance and cohesion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1975;32(2):346–360. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.32.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huesmann LR, Moise-Titus J, Podolski CL, Eron LD. Longitudinal relations between children's exposure to TV violence and their aggressive and violent behavior in young adulthood: 1977–1992. Dev Psychol. 2003;39(2):201–221. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, et al. The influence of media violence on youth. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2003;4(3):81–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-1006.2003.pspi_1433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood W, Wong FY, Chachere JG. Effects of media violence on viewers' aggression in unconstrained social interaction. Psychol Bull. 1991;109(3):371–383. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.109.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushman BJ, Anderson CA. Media violence and the American public: scientific facts versus media misinformation. Am Psychol. 2001;56(6–7):477–489. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.6-7.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bushman BJ, Huesmann LR. Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(4):348–352. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnagey NL, Andersen CA, Bushman BJ. The effect of video game violence on physiological desensitization to real-life violence. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43(3):489–496. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murray JP, Liotti M, Ingmundson PT, et al. Children's brain activations while viewing televised violence revealed by fMRI. Media Psychol. 2006;8(1):25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brady SS, Matthews KA. Effects of media violence on health-related outcomes among young men. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(4):341–347. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.4.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Pediatrics; American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; American Psychological Association; American Medical Association; American Academy of Family Physicians; American Psychiatric Association. Joint statement on the impact of entertainment violence on children: Congressional Public Health Summit. [April 29, 2008]; Available at: www.aap.org/advocacy/releases/jstmtevc.htm.

- 11.Wilson B, Kunkel D, Linz D, et al. National Television Violence Study. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Violence in television programming overall: University of California, Santa Barbara study; pp. 5–204. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puig C. “Hannibal” ignites world wide ratings controversy. USA Today. 2001:D06. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent JD, Heatherton TF, Ahrens MB, Dalton MA, Tickle JJ, Beach ML. Adolescent exposure to extremely violent movies. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(6):449–454. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Dalton MA, et al. Effect of seeing tobacco use in films on trying smoking among adolescents: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;323(7326):1394–1397. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson CA, Carnagey NL, Eubanks J. Exposure to violent media: the effects of songs with violent lyrics on aggressive thoughts and feelings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(5):960–971. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blosser BJ. Ethnic differences in children's media use. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1988;32(4):453–470. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shalala D. Prevalence of violent behavior. [April 29, 2008];Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2001 Available at: http://download.ncadi.samhsa.gov/ken/pdf/surgeon/SG.pdf.

- 19.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: Media in the Lives of 8–18 Year Olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [April 29, 2008]. Available at: www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/Generation-M-Media-in-the-Lives-of-8-18-Year-olds-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Trade Commission. Marketing Violent Entertainment to Children: A Review of Self-regulation and Industry Practices in the Motion Picture, Music Recording and Electronic Game Industries. Washington, DC: 2000. Available at: www.ftc.gov/reports/violence/vioreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.