Abstract

Background

With the world's largest population, HIV spread in China has been closely watched and widely studied by its government and the international community. One important factor that might contribute to the epidemic is China's numerous surplus of men, due to its imbalanced sex ratio in newborns. However, the sex ratio in the human population is often assumed to be 1:1 in most studies of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Here, a mathematical model is proposed to estimate the population size in each gender and within different stages of reproduction and sexual activities. This population profiling by age and gender will assist in more precise prediction of HIV incidences.

Method

The total population is divided into 6 subgroups by gender and age. A deterministic compartmental model is developed to describe birth, death, age and the interactions among different subgroups, with a focus on the preference for newborn boys and its impact for the sex ratios. Data from 2003 to 2007 is used to estimate model parameters, and simulations predict short-term and long-term population profiles.

Results

The population of China will go to a descending track around 2030. Despite the possible underestimated number of newborns in the last couple of years, model-based simulations show that there will be about 28 million male individuals in 2055 without female partners during their sexually active stages.

Conclusion

The birth rate in China must be increased to keep the population viable. But increasing the birth rate without balancing the sex ratio in newborns is problematic, as this will generate a large number of surplus males. Besides other social, economic and psychological issues, the impact of this surplus of males on STD incidences, including HIV infections, must be dealt with as early as possible.

Background

HIV/AIDS spread in China has been an increasingly growing concern since the first AIDS case was reported in Beijing [1]. When a joint assessment by the Chinese government, UN and WHO suggested in 2005 [2] that there were 650,000 individuals living with HIV/AIDS and 75,000 had developed AIDS, some claim that future incidence could rise up to 10-15 million cases by 2010 [3]. With the largest population in the world, China must maintain and strengthen its efforts to control the epidemic including raising awareness and prevention of the disease among risk groups: injecting drug users (IDUs), former plasma donors, men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, etc. Another possible high-risk group that is rarely studied is the surplus men. According to a study by J.D. Tucker and colleagues in 2005 [4], most people in this group are young, unmarried, poor, unemployed and less educated and are therefore more likely to turn to sex workers; consequently, the number of sex workers is likely to be increased due to the sexual demand from surplus men. Both factors increase the average sexual partner exchange rate, and a higher partner exchange rate normally leads to a larger HIV incidence rate [5].

However, sex ratio in the human population is often assumed to be 1:1 in most studies of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). More specifically, the population is generally divided into certain subgroups based on gender, sexual behaviour and stage of disease development; the change rate of population in each subgroup is often assumed to be a function of the natural population growth, the nature of disease and the size of all other groups; the natural growth of the human population is usually believed to be proportional to the size of total population [5-9] (and references therein); and the sex ratio is balanced. This is normally true for a society with a stable age structure. But it is different for countries with rapid social and economical changes. For example, according to United Nation [10], the male population in China in the sexually active stage will decrease from 29% in 2000 to 23% in 2030, while the sex ratio in the same group will increase from 1.066 to 1.12.

There are many problems that might be caused by gender imbalance, such as antisocial behaviour and violence threatening the social stability, women trafficking and expansion of the sex industry [11]. Another major issue that deserves serious attention is the impact of gender imbalance on the spread of STDs, especially those STDs such as HIV/AIDS with long incubation periods and with different stages of disease progression.

Although a study proposed by T. E. Senn et al. [12] suggests that there is no association between the sex ratio and the number of sexual partners in African Americans, it is commonly believed that the surplus men will turn to sex workers for sexual service, especially when they cannot afford regular sex partners [4]. A. Ebenstein and E. Jennings in 2008 [13] found that most counties with a high rate of single men tend to be regions with a high rate of men paying for sex. They also claimed that 9% of men will pay for sex in 30 years, rising from 6% in 2005, partially because of the increasing number of unmarried men. Other reasons for the ascending trend of commercial sex activity include various social and cultural changes driven by economic reform since 1976. The high rate of men purchasing sex seems to be occupation related. In [13], the authors noted the relationship between the percentage of men working in the construction industry and the prevalence of commercial sex activity. Other relevant studies include the work of B. Wang et al. [14] and a report by R. Zhao et al. [15]. The former found 10% of a total of 1,304 rural-to-urban migrant men paid for sex; the latter claimed that 9.4% of 232 miners in townships of Yunnan province purchased sex, while 9% of Chinese men in a similar age range purchased sexual services [16]. Regardless of the different focuses of these studies, all authors seem to agree that male clients of female sex worker in China need to be studied more, given the high rate of HIV/AIDS infection and its role of bridging the high-risk groups and the general population in the HIV/AIDS transmission. When surplus men become surplus clients [17], HIV/AIDS incidences may rise rapidly.

The disproportionate surplus men may also increase homosexual activities. Although there is no solid evidence as far as we know that suggests surplus men in China have higher level of homosexual behaviours than other demographic groups, especially when the sex service is sufficiently supplied by female sex workers, it is wildly believed that homosexual behaviours are common in certain male concentrated places like prison [18] and the army [19]. Nevertheless, the general public may become more tolerant to homosexual behaviour and more hidden homosexuals may publicly express their sexualities [11]. Since unprotected same-sex behaviour is well known for its high risk in spreading HIV/AIDS [20], an extraordinarily off-balanced male population may contribute to the increase of HIV/AIDS in the future. It is therefore important to make accurate predictions of the profile of populations in terms of gender and stages of sexual activities. This is certainly a very difficult task. For example, the UN claimed in 1951 that the world population in 30 years would be 2.976 - 3.636 × 109 [21] but it was 4.45 × 109 in 1980. We note that the 1986 UN estimation of the world population 6 × 109 in 2000 [22] was close to the actual number, 6.1 × 109. Predicting the population in countries such as China is certainly no less challenging, though some efforts have been made [23-26].

One factor contributing to the difficulty in predicting the population is the fast-growing economy. In less than 30 years, China has increased its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 364.52 billion yuan in 1976 to 21,087.1 billion yuan in 2006. GDP index per capita in 2006 is almost 10 times that of 1976 [27]. The skyrocketing economy brought Chinese people a better life, as well as a lower birth rate that has been observed in developed countries during their development (Figure 1). The negative correlation between economic success and population growth is probably due to the trade-off between quantity and quality of children [28,29]. It would be difficult to use this correlation alone to predict the population in China, since not only the quality of raising children but also the rate of consumption of other commodities is expected to be different in coming decades.

Figure 1.

GDP index, birth rate and death rate in China. Source: Statistics China [27].

Another reason that we should not consider the number of children just as a function of economy is the China's unique one-child policy. In 1970s, China's leaders worried that its swelling population could consume any effect to improve the quality of Chinese people's life. This worry was based on Malthusian Theory [30], which argues that population grows geometrically and that the food supply increases only at an arithmetic rate. Famine is hence inevitable unless constraints are applied to population growth. A planned-birth policy was introduced in 1973 and the one-child-per-couple policy became a national law in 1980 [31]. Although certain exceptions exist among ethnic minorities and in rural areas [32], most couples in China only have one child. Adding to the difficulty of predicting the population size in China is the abnormal gender imbalance among newborns. It is reported, for example, by Statistics China, that the average male-female ratio was 121.8 from 2003 to 2007 [27].

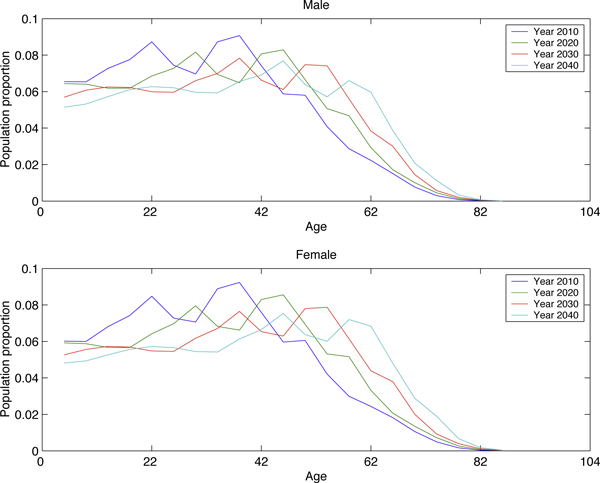

In this study, we compartmentalize the total population into 6 sex-age subgroups. The age structure is explicitly introduced because of a possible unstable age structure in the coming decades illustrated in Figure 2. A possible reason for the changing age structures is the comparatively large variance in the birth rate back in 1980s and 1990s, as shown in Figure 1. Our model incorporates the sex-ratio imbalance in newborns. Although this ratio is normally around 1.05 in a large population [33], China has a much higher sex ratio: 1.15 estimated by the UN [10]; data from Statistics China is even more dramatic [27]. A similar phenomenon seems to have been reported in India (1.08), Mauritania (1.08) and South Korea (1.1). Fertility decline and son preference are wildly believed to be two main reasons [34] to select sex in birth. Li et al. [35] established some quantitative relations among sex ratio at birth, fertility, and son preference. China, as one can imagine, has the worst scenario due to the one-child-policy and its long-lasting son preference [36].

Figure 2.

Age structure of male and female in China. Source: UN [10].

Existing studies of the population size with consideration of gender imbalance include the work of Yellin et al. [37], where a dynamic system with three compartments - single individuals with two sexes, N1 and N2, and married couples, T3 - is constructed. A match function with variables N1 and N2 was introduced in order to estimate the new cases in T3. Our study differentiates from the aforementioned work by considering the rate of newborns as a function of the sizes of sexually active male and female populations. This is described by our proposed matching function, that needs to incorporate the so-called minimum viable population (MVP) in order to avoid the singularity at the trivial equilibrium state. Such an MVP size was introduced in [38-40] to represent the minimum number of individuals in a population in order for the species under consideration to survive.

Methods

Mathematical model

The total population is divided into 6 subgroups determined by gender (Male (M) and Female (F)) and stage of ages (stage 1: age 0 to age 14; stage 2: age 15 to age 49; and stage 3: age 50 and beyond). The second group will be important for reproduction and sexually transmitted infections. The sizes of these subgroups will be denoted by M1, M2, M3, F1, F2, F3, respectively. For example, M2 is the size of the male population aged 15 to 49.

The population change of each subgroup is the number of individuals entering minus those leaving this subgroup. More specifically, the inflow to stage 1 is due to the birth of newborns, while the inflow to and the outflow from stages 2 and 3 are due to aging and death. Note that people only leave age group 3 due to death.

The number of newborns is determined by a matching function C := C(M2, F2), similar to the match function introduced in [37], of the populations in stage 2 in both genders. It is natural to require the following properties of the matching function:

• C(M2, F2) = 0 if either M2 = 0, or F2 = 0, or both;

• C(M2, F2) is an increasing function of either variable if another is fixed;

• C ∝ M2 if F2 ≫ M2, and C ∝ F2 when M2 ≫ F2.

Two obvious functions satisfying the above properties are C ∝ min(μMM2, μFF2) and  where μM and μF are the average number of reproductive partners that one individual can have. In our simulations, we choose the second one due to its smoothness. In this case, since monogamy is still the main marriage system in the modern society, we assume that μM = μF = 1.

where μM and μF are the average number of reproductive partners that one individual can have. In our simulations, we choose the second one due to its smoothness. In this case, since monogamy is still the main marriage system in the modern society, we assume that μM = μF = 1.

The above function has a singularity at the equilibrium when M2 = F2 = 0. On the other hand, as stage 2 in our model is responsible for reproduction, it is natural to assume a minimal size must be maintained at this stage. Following the theory of minimum viable population (MVP) (see [38-40]), we will use the modified function  , where ϵ is a small positive number: the specific value of ϵ is not important for our simulations and analysis, as long as it is relatively small. This implies that C(M2, F2) ≈ 0 if M2 + F2 << ϵ. Furthermore, the population growth is limited by the carrying capacity [41] so that the reproduction rate decreases when the population size is greater than the capacity. Consequently, we will use the following matching function throughout the reminder of this paper:

, where ϵ is a small positive number: the specific value of ϵ is not important for our simulations and analysis, as long as it is relatively small. This implies that C(M2, F2) ≈ 0 if M2 + F2 << ϵ. Furthermore, the population growth is limited by the carrying capacity [41] so that the reproduction rate decreases when the population size is greater than the capacity. Consequently, we will use the following matching function throughout the reminder of this paper:

with N being the size of the total population and K relevant to the carrying capacity.

Therefore, the deterministic compartmental model for a population stratified by genders and ages is as follows:

Parameters and their estimation

A description of the model parameters, along with their values (to be used in our simulations) and relevant references, can be found in Table 1. Note that  is the number of newborns per unit time. In our simulations, we estimate the value of μ and K by using the nonlinear least square estimation (LSE) to estimate the model-generated numbers against the reported newborns in 2003, 2004 and 2005 (the initial value of K comes from [42], and the initial value of μ is determined by taking the initial K and other parameters in 2003). Note that, unless otherwise specified, values of other parameters are taken from [27].

is the number of newborns per unit time. In our simulations, we estimate the value of μ and K by using the nonlinear least square estimation (LSE) to estimate the model-generated numbers against the reported newborns in 2003, 2004 and 2005 (the initial value of K comes from [42], and the initial value of μ is determined by taking the initial K and other parameters in 2003). Note that, unless otherwise specified, values of other parameters are taken from [27].

Table 1.

Parameters estimated from Statistics China [27].

| Parameter | Description | Value | Unit | Estimation description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ | Birth rate | 0.11584 | Proportion | Estimated using LSE |

| σ | Males in newborns | 0.5487 | Proportion | Average ratio of age 0-4 in 2003-2007 |

|

Growth rate of age group 1 | 1/15 | Proportion | Inverse of time in age group 1 |

|

Growth rate of age group 2 | 1/35 | Proportion | Inverse of time in age group 2 |

|

Death rate of male in age group 1 | 0.00122 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

|

Death rate of female in age group 1 | 0.00122 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

|

Death rate of male in age group 2 | 0.0022 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

|

Death rate of female in age group 2 | 0.0012 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

|

Death rate of male in age group 3 | 0.0242 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

|

Death rate of female in age group 3 | 0.0189 | Proportion | Average rate in 2003-2007 |

| ϵ | MVP | 0.05 | 104 individuals | Source: [48] |

| K | Carrying capacity parameter | 549186 | 104 individuals | Estimated using LSE |

| M1 | Males in age group 1 | 14072.82 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

| F1 | Females in age group 1 | 12211.95 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

| M2 | Males in age group 2 | 37333.68 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

| F2 | Females in age group 2 | 36286.94 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

| M3 | Males in age group 3 | 14563.88 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

| F3 | Females in age group 3 | 14744.8 | 104 individuals | Initial population in 2003 |

Results and Discussion

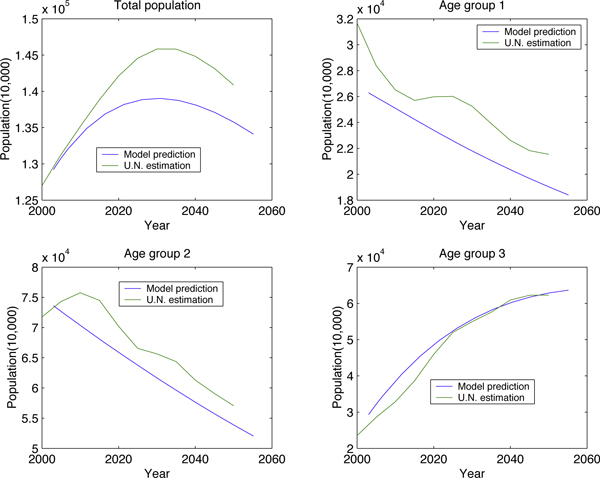

Simulations based on our models show that China's population will decrease around 2030, which is consistent with the estimation from UN; see Figure 3. Other agreements include the changing trend of each age group and gender group, see Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Model estimation v.s. U.N. by population density in each age groups.

Figure 4.

Model estimation v.s. U.N. by number of extra males in each age group.

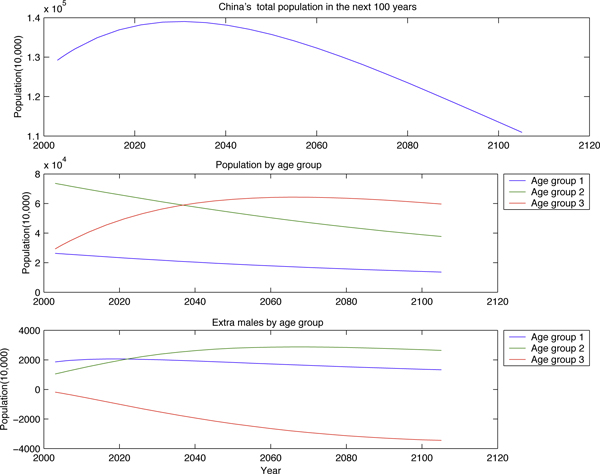

Assuming that the birth ratio and birth rate remain unchanged for the next 100 years, we examine how the China's population and its age-sex structure change in the future. We can see from Figure 5 that China's population will decrease around the year 2030. We can also see an aging China coming: a China with a shrinking population and with a larger portion of aged individuals.

Figure 5.

China's population in 100 years.

The main motivation for this study is the sex imbalance; we will address the impact of this imbalance on the spread of STDs in a subsequent study. Our simulations show that there will be about 28 million male individuals in 2055 who will not have female partners during their sexually active ages (Figure 4). In China, these male individuals are called Guanggun, that is, bare branch. The social, economic and health issues caused by this subpopulation must be addressed.

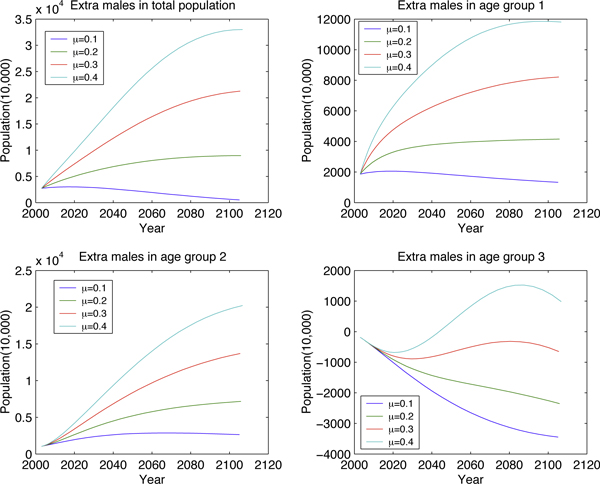

Fixing μ (birth rate) and varying σ (proportion of newborn males) (Figure 6 and Figure 7) illustrates how the high sex-ratio imbalance in newborns affects the population structure. Similar manipulations to μ are presented in Figure 8 and Figure 9. These figures show that σ is less significant than μ in changing population size but it will tremendously deteriorate the sex ratio in adults.

Figure 6.

Long-term effect to age group by varying σ.

Figure 7.

Long-term effect to the number of extra males by varying σ.

Figure 8.

Long-term effect to age group by varying μ.

Figure 9.

Long-term effect to the number of extra males by varying μ.

Conclusion

Unlike other countries, China has a tough and much-criticized policy to control its population growth. It is the national law that most couple in China can have only one child. This policy was effectively executed: total fertility has dropped from 4.86 in 1970s to 1.70 in the 21st century [10]. Meanwhile, the world's total fertility is 2.65 and that of developed countries is 1.56. Not intending to address all the controversies around this policy, we attempt to describe the population profiles under this policy and the related sex-ratio imbalance in newborns.

We found that this sex-ratio imbalance will decrease the population growth when the birth rate is fixed, although this negative effort can be balanced by increasing the birth rate. There will be an abnormally large number of male individuals without female partners during their sexually active stages in the next several decades if the sex-ratio imbalance in newborns is not reduced. The sexual demands from these surplus men may increase the high-risk heterosexual or homosexual activities and thereafter increase HIV/AIDS and other STD/STI incidences. The impact of these surplus males on STD incidence should therefore be addressed urgently.

There are also other interesting sociological and psychological issues arising from the shortage of women. Discrimination against women may be undermined [43]; bride trading was reported [44]; polyandry may be normalized [45]; crimes against women such as rape may rise [46], although some researchers claim that rape against women may decline because of the booming sex industry [47]. More efforts are required to examine each of these issues.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the formulation of mathematical models. YP designed and conducted the model-based simulations and the estimation of model parameters from the literature.

Contributor Information

Yuanyi Pan, Email: yuanyi@mathstat.yorku.ca.

Jianhong Wu, Email: wujh@mathstat.yorku.ca.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Mathematics for Information Technology and omplex Systems (MITACS), by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and by the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) Program.

This article has been published as part of BMC Public Health Volume 9 Supplement 1, 2009: The OptAIDS project: towards global halting of HIV/AIDS. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/9?issue=S1.

References

- AP. China Says Argentine Died of AIDS. Tech rep, New York Times; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- China W UNAIDS. 2005 Update on the HIV/AIDS Epidemic and Response in China. Beijing, China: China CDC; 2006. Http://data.unaids.org/publications/External-Documents/rp_2005chinaestimation_25jan06_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- NIC. The Next Wave of HIV/AIDS: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Russia, India, and China. Washington, US: National Intelligence Council; 2002. Http://www.dni.gov/nic/PDF_GIF_otherprod/HIVAIDS/ICA_HIVAIDS20092302.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Tucker J, Henderson G, Wang T, Huang Y, Parish W, Pan S, Chen X, Cohen M. Surplus men, sex work, and the spread of HIV in China. AIDS. 2005;19:539–547. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163929.84154.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R, May RM. Infectious diseases of humans: Dynamics and control. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- May R, Anderson R. Transmission dynamics of HIV infection. Nature. 1987;326:137–142. doi: 10.1038/326137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnett GP, Aral SO, Hoyle DV, WC Jr, Anderson RM. The natural history of syphilis. Implications for the transmission dynamics and control of infection. Sexually transmitted diseases. 1997;24(4):185–200. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hethcote HW, Yorke JA. Gonorrhea Transmission Dynamics and Control. Vol. 56. Springer; 1984. [Lecture Notes in Biomathematics]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KM, Adams EJ, Gay N, Ghani AC, Mercer C, Edmunds WJ. Developing a realistic sexual network model of chlamydia transmission in Britain. Theoretical biology and medical modelling. 2006;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNDESA. World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects: The 2005 Revision. United Nations; 2007. Http://esa.un.org/unpp/index.asp?panel=2 [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh T, Zhu W. Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: Causes and consequences. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Online (US) 2006;103(36):13271–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602203103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, Urban MA, Sliwinski MJ. The Male-to-Female Ratio and Multiple Sexual Partners: Multilevel Analysis with Patients from an STD Clinic. AIDS and Behavior. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ebenstein AY, Jennings E. Gender Policy and HIV in China. Springer chap. 'Bare Branches', Prostitution, and HIV in China: A Demographic Analysis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Li X, Stanton B, Fang X, Lin D, Mao R. CHINA: HIV-Related Risk Behavior and History of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among Male Migrants Who Patronize Commercial Sex in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2007;34:1–8. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000222668.95038.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, Gao H, Shi X, Tucker JD, Yang Z, Min X, Qian H, Duan Q, Wang N. Sexually Transmitted Disease/HIV and Heterosexual Risk Among Miners in Townships of Yunnan Province, China. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2005;19(12):848–852. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish WL, Laumann E, Cohen MS, Pan S, Zheng H, Hoffman I, Wwang T, NG KH. Population-based study of chlamydial infection in China: a hidden epidemic. the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(10):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirkle C, Soundardjee R, Stella A. Female Sex Workers in China: Vectors of Disease? Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2007;34(9):695–703. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000260989.70866.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eigenberg HM. Homosexuality in Male Prisons: Demonstrating the Need for a Social Constructionist Approach. Criminal Justice Review. 1992;17(2):219–234. doi: 10.1177/073401689201700204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones FD, Koshes RJ. Homosexuality and the military. the American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:16–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BC, Chu QS. MSM and HIV/AIDS in China. Cell Research. 2005;15:858–864. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UN. Demographic Yearbook. New York: United Nations; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- UNDIESA. Demographic Yearbook. New York: United Nations; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Spence N. Modelling urban-rural population growth in China. Environment And Planning A. 1996;28(8):1417–44. doi: 10.1068/a281417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Spence N. Modelling regional population growth in China. Mathematical Population Studies. 1997;6(3):241–74. doi: 10.1080/08898489709525434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J. China's Future Population and Development Challenges. The Geographical Journal. 1998;164:32–40. doi: 10.2307/3060543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Jiang Z. Analyzing the prospect of population development in China. Chinese Journal Of Population Science. 1996;8:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NBSC. Statistical yearbook. China Statistical Press; 2007. Http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/statisticaldata/yearlydata/ [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. An Economic Analysis of Fertility. Demographic and Economic Changes in Developed Countries. 1960. pp. 209–231.

- Becker G, Lewis H. On the Interaction between the Quantity and Quality of Children. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81(2):S279–88. doi: 10.1086/260166. http://ideas.repec.org/a/ucp/jpolec/v81y1973i2ps279-88.html [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malthus T. An Essay on the Principle of Population. No. malthus1798 in History of Economic Thought Books, McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought; 1798. http://ideas.repec.org/b/hay/hetboo/malthus1798.html [Google Scholar]

- Agency XN. The beginning and development of China's Planned-Birth-policy (Translated) News. 2002.

- SCPC P. Provincial planned-birth-policies(Translated) Web. 2003. Http://www.china.com.cn/zhuanti2005/node_5457646.htm

- Chahnazarian A. Determinants of the sex ratio at birth: Review of recent literature. Social Biology. 1988;35:214–235. doi: 10.1080/19485565.1988.9988703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Feldmanc MW, Li S. Cultural Transmission in a Demographic Study of Sex Ratio at Birth in China's Future. Theoretical Population Biology. 2000;58:161–172. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2000.1478. Http://www.china.com.cn/zhuanti2005/node_5457646.htm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Feldmanc MW, Tuljapurkar S. Sex ratio at birth and son preference. Mathematical Population Studies. 1999;8:91–107. doi: 10.1080/08898480009525475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poston DL. Son preference and fertility in China. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2002;34:333–347. doi: 10.1017/S0021932002003334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yellin J, Samuelson PA. A Dynamical Model for Human Population. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United State of America. 1974;71(2):2813–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.7.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer ML. Minimum Population Sizes for Species Conservation. BioScience. 1981;31(2):131–134. doi: 10.2307/1308256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin ME, Soule ME. Minimum viable populations: The processes of species extinctions. Sunderland Mass: Sinauer Associates chap. Conservation biology: The science of scarcity and diversity; 1986. pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Soule ME, (Ed) Viable Populations for Conservation. Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Daily GC, Ehrlich PR. Population, Sustainability, and Earth's Carrying Capacity. BioScience. 1992;42(10):761–771. doi: 10.2307/1311995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao M, Ma S, Han C. Potential Productivity and Human Carrying Capacity of an Agro-Ecosystem: An Analysis of Food Production Potential of China. Agricultural Systems. 1995;47(4):387–414. doi: 10.1016/0308-521X(95)92106-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Missing girls in South Korea: Trends, levels and regional variations. Population-English. 2004;59(6):865–878. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V. Declining sex ratio forces import of brides. News, The Hindu; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mann K. Tribal women: on the threshold of Twenty-first century. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V. Crime against women on the rise in Punjab, Haryana. News, The Hindu; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cundiff KR. Prostitution and Sex Crimes. 50. the Independent Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin IR. Conservation Biology: An Evolutionary-Ecological Perspective. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, U.S.A., chap. Evolutionary change in small populations; 1980. pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]