Abstract

Up to 17% of hospital admissions are complicated by serious adverse events unrelated to the patients presenting medical condition. Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) review patients during early phase of deterioration to reduce patient morbidity and mortality. However, reports of the efficacy of these teams are varied. The aims of this article were to explore the concept of RRT dose, to assess whether RRT dose improves patient outcomes, and to assess whether there is evidence that inclusion of a physician in the team impacts on the effectiveness of the team. A review of available literature suggested that the method of reporting RRT utilization rate, (RRT dose) is calls per 1,000 admissions. Hospitals with mature RRTs that report improved patient outcome following RRT introduction have a RRT dose between 25.8 and 56.4 calls per 1,000 admissions. Four studies report an association between increasing RRT dose and reduced in-hospital cardiac arrest rates. Another reported that increasing RRT dose reduced in-hospital mortality for surgical but not medical patients. The MERIT study investigators reported a negative relationship between MET-like activity and the incidence of serious adverse events. Fourteen studies reported improved patient outcome in association with the introduction of a RRT, and 13/14 involved a Physician-led MET. These findings suggest that if the RRT is the major method for reviewing serious adverse events, the dose of RRT activation must be sufficient for the frequency and severity of the problem it is intended to treat. If the RRT dose is too low then it is unlikely to improve patient outcomes. Increasing RRT dose appears to be associated with reduction in cardiac arrests. The majority of studies reporting improved patient outcome in association with the introduction of an RRT involve a MET, suggesting that inclusion of a physician in the team is an important determinant of its effectiveness.

Introduction

There are many conditions in medicine for which there is a relationship between the dose of therapy given and the response to such therapy. This dose-response is seen in every day practice in relation to diuretics for the treatment of fluid overload, fluid therapy for volume depletion, catecholamines for shock, and oxygen supplementation for hypoxemia.

Amounts of delivered therapy are also likely to be important determinants of outcome for systems of care. Thus, nurse staffing levels have been shown to impact on rates of complications in hospitalized patients [1,2], and outcomes of cancer surgery are better in high volume institutions [3].

In this article, we briefly review the background to the role of the Rapid Response Team (RRT) in preventing serious adverse events (SAEs) in hospitalized patients. We also introduce the concept of 'RRT dose', the number of RRT activations per 1,000 admissions or discharges. In addition, we highlight possible differences in RRT composition that might indirectly affect 'dose', and stress the importance of physician inclusion in relation to the types of therapy the RRT can deliver. Finally, we emphasize the importance of RRT dose in preventing SAEs in hospitalized patients.

The background to the Rapid Response Team concept

Multiple studies around the world have demonstrated that patients admitted to hospitals suffer SAEs at a rate of between 2.9% [4] and 17% [5] of cases. Such events may not be directly related to the patient's original diagnosis or underlying medical condition. Of greater concern, these events may result in prolonged length of hospital stay, permanent disability, and even death in up to 10% of cases.

Other studies have shown that these events are frequently preceded by signs of physiological instability that manifest as derangements in commonly measured vital signs [6-9]. Such derangements form the basis for RRT activation criteria used in many hospitals.

When patients fulfill one or more criteria, ward staff activate the RRT, which then reviews and treats the patient. The Medical Emergency Team (MET) differs from other RRTs in that the team leader is a physician, typically with intensive care expertise. Other RRTs include Critical Care Outreach teams in the United Kingdom, which may form part of a graded escalation in care and are usually nurse led. The tenet underlying the MET concept is that early activation and intervention by a suitably trained team improves outcome. As stated by England and Bion [10], the principle of the MET is to 'take critical care expertise to the patient before, rather than after, multiple organ failure or cardiac arrest occurs.'

The findings of the first consensus conference on RRTs have been recently published [11]. This document defined the Rapid Response System (RRS) as the whole system providing a safety net for acutely unwell ward patients. The RRS has four components: an afferent limb for 'crisis detection' and triggering of the RRT; an efferent or responder limb, which is the RRT itself; a governance and administrative structure; and a quality improvement arm [11].

The concept of Rapid Response Team 'dose'

It has been suggested that the standard method for reporting RRT utilization rate should be RRT calls per 1,000 patient admissions or discharges [11]. This measurement assesses the rate of crisis detection and afferent limb activation. A progressive increase in MET utilisation has been demonstrated at a teaching hospital in Melbourne, Australia [12]. In April 2004, the dose of MET calls was 40.6 per 1,000 admissions. Patients admitted on surgical wards received a much higher rate of MET review than medical patients [12].

Other studies of physician-led METs in Pittsburgh, USA [13], Ottawa, Canada [14], and Sydney, Australia [15] have reported MET doses of 25.8, 40.3 and 56.4 calls per 1,000 admissions, respectively. The last rate equates to 5.64% of all admissions being reviewed by the MET, and is similar in proportion to the rates of SAEs seen in most studies.

Increasing Medical Emergency Team dose improves patient outcome

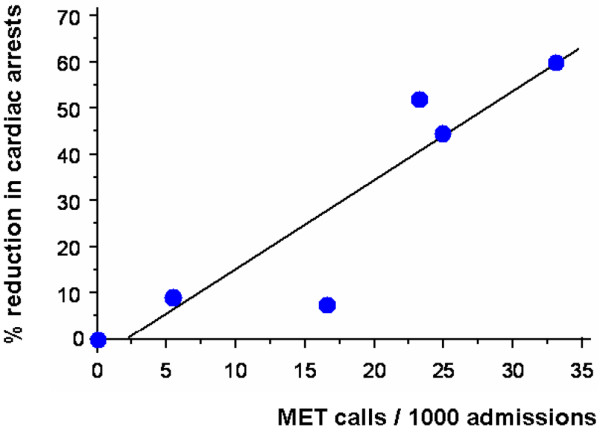

The first evidence of a dose-response effect of the MET was demonstrated by DeVita and co-workers in Pittsburgh [13]. Introduction of objective MET calling criteria resulted in a significant increase in MET call rates (from 13.7 to 25.8 per 1,000 admissions). This was associated with a 17% reduction in cardiac arrest rates. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that increasing MET dose at a teaching hospital in Melbourne was associated with a progressive and dose-related reduction in the incidence of cardiac arrests in ward patients [16]. This study suggested that for every additional 17 MET calls, one cardiac arrest might be prevented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot and line of regression showing association between increased Medical Emergency Team (MET) call rate ('MET dose') and percentage reduction in cardiac arrest rate from baseline. Adapted from Jones and colleagues [16].

Further evidence of a dose-response of the MET on cardiac arrests was suggested by an analysis of the circadian variation of detection of cardiac arrests and MET review activations over a 24-hour period [17]. Thus, cardiac arrests were most common overnight when MET reviews were least frequent. Similarly, cardiac arrests were least frequent in the evening, when MET review rate (or dose) was the highest [17].

Recently, Buist and co-workers [18] also reported on the long-term effect of increasing MET dose on cardiac arrests in a large urban hospital in Melbourne, Australia. Increase in the rate of MET reviews with time resulted in a reduction in cardiac arrests of 24% per year. Importantly, none of these studies provide information on the mechanism by which the MET may achieve such reductions. These may include increased do-not-resuscitate (DNR) designations and end of life care planning [19], improved ward staff education [20], improved documentation [21], rescue of unstable patients that may have proceeded to arrest without MET intervention, or any combination of the above factors.

A separate study at a teaching hospital in Melbourne, Australia assessed the effect of the MET on in-hospital surgical and medical mortality in the 4 years after its introduction [22]. Implementation of the MET was associated with a reduction in mortality in surgical but not medical patients. This observation may be due, in part, to the relative dose of MET review for each patient population. Thus, in surgical patients the rate of MET review exceeded the death rate for virtually the entire duration of the study. In contrast, for medical patients, the death rate exceeded the rate of MET review [22]. Put simply, if the MET is a major method of prevention of SAEs on the ward, the rates of MET review should be similar to, if not greater than, rates of SAEs.

The MERIT study involved a cluster randomized controlled trial of 23 Australian hospitals in which 12 introduced a MET and 11 continued with ongoing usual care. The introduction of a MET resulted in increased emergency call rates but did not statistically reduce the combined incidence of cardiac arrests, unexpected deaths and unplanned ICU admissions [23]. Importantly, the rate of emergency review calls in the Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy (MERIT) study was only 8.3 per 1,000 admissions (0.83%) during the 6-month period following the intervention. As this figure also included cardiac arrest team calls, it probably represents an overestimate of actual MET calls. Insufficient review rates may, in part, explain the lack of positive results reported in this study.

The MERIT study investigators also recently reported on the relationship between 'MET-like activity' and serious adverse events. This study, comprising all 23 participating hospitals and 741,744 admissions, revealed that there was a negative relationship between the proportion of RRT calls that were early emergency team calls and the rates of unexpected cardiac arrests, overall cardiac arrests, and unexpected deaths [24]. This further supports the view that the more preventive intervention by an emergency team is delivered, the lower the number of cardiac arrests.

The dose of the Rapid Response System efferent arm

Most studies demonstrating the effectiveness of RRTs on outcomes of in-hospital patients have involved a physician-led MET (Table 1). Priestly and colleagues [25] reported a reduction in in-hospital mortality associated with the introduction of a Critical Care Outreach service using a nurse-led RRT in a single-centre cluster randomized ward-based trial. A recent American before-and-after study involving a nurse-led RRT reported a reduction in mean hospital-wide code rates following the introduction of the RRT. However, this difference did not remain significant after adjustment for case mix [26].

Table 1.

Summary of studies of Rapid Response Teams involving comparison dataa

| Study and yearb | Study design | Team leader | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bristow et al. 2000 [32] | Case control cohort study. Comparison between one MET hospital and two cardiac arrest team hospitals | Doctor | Fewer unanticipated ICU/high dependency unit admissions in MET hospital. No difference in in-hospital cardiac arrests or mortality |

| Buist et al. 2002 [30] | Before (1996) and after (1999) study. MET introduced in 1997 and activation criteria simplified 1998 | Doctor | Reduction of cardiac arrest rate from 3.77 to 2.05/1,000 admissions. OR for cardiac arrest after adjustment for case mix = 0.50 (95% CI 0.35 to 0.73) |

| Bellomo et al. 2003 [29] | Before (4 months 1999) and after (4 months 2000 to 2001) 1-year preparation and eduction period | Doctor | RRR cardiac arrests 65% (P < 0.001). Decreased bed days cardiac arrest survivors (RRR 80%, P < 0.001). Reduced hospital mortality (RRR 26%, P = 0.004) |

| Bellomo et al. 2004 [33] | Time periods and design as above. Assessment of effect of MET on serious adverse events following major surgery | Doctor | Reduction in serious adverse events (RRR 57.8%, P < 0.001), emergency ICU admissions (RRR 44.4%, P = 0.001), postoperative deaths (RRR 36.6%, P = 0.0178), and hospital length of stay (P = 0.0092) |

| Kenward et al. 2004 [34] | Before and after (October 2000 to September 2001) introduction of MET | Doctor | Decreased deaths (2.0% to 1.97%) and cardiac arrests (2.6/1,000 to 2.4/1,000 admissions). Not significant |

| DeVita et al. 2004 [31] | Retrospective analysis of MET activations and cardiac arrests over 6.8 years | Doctor | Increased MET use (13.7 to 25.8/1,000 admissions) was associated with 17% reduction cardiac arrests (6.5 to 5.4/1,000 admissions, P = 0.016) |

| Priestly et al. 2004 [25] | Single-centre ward-based cluster randomized control trial of 16 wards | Nursec | Critical care outreach reduced in-hospital mortality (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.85) compared with control wards. |

| MERIT 2005 [23] | Cluster randomized trial of 23 hospitals in which 12 introduced a MET and 11 maintained only a cardiac arrest team. Four-month preparation period and 6-month intervention period |

Doctor | Increased overall call rates (3.1 versus 8.7/1,000 admissions, P = 0.0001). No decrease in composite end point of cardiac arrests, unplanned ICU admissions and unexpected deaths |

| Jones et al. 2005 [16] | Long-term before (8 months 1999) and after (4 years) introduction of MET | Doctor | Decreased cardiac arrests (4.06 to 1.9/1,000 admissions; OR 0.47, P < 0.0001). Inverse correlation between MET rate and cardiac arrest rate (r2 0.84, P = 0.01) |

| Jones et al. 2007 [22] | Long-term before (September 1999 to August 2000) and after (November 2000 to December 2004) study. Effect on all-cause hospital mortality | Doctor | Reduced deaths in surgical patient compared with 'before' period (P = 0.0174). Increased deaths in medical patients compared with 'before' period (P < 0.0001) |

| Jones et al. 2007 [35]z | Time periods of design as per [29]. Study assessed long-term (4.1 years) survival of major surgery cohort | Patients admitted in the MET period had a 4.1-year survival rate of 71.6% versus 65.8% for control period. Admission during MET period was an independent predictor of decreased mortality (OR 0.74, P = 0.005) | |

| Buist et al. 2007 [18] | Assessment of MET call rates and cardiac arrests between 2000 and 2005 | Doctor | Increased MET use was associated with reduction in cardiac arrest of 24% per year, from 2.4 to 0.66/1,000 admissions |

| Jones et al. 2008 [36] | Multi-centre before-and-after study. Assessment of cardiac arrests admitted from ward to ICU before and after introduction of RRT | Varied | Continuous data only available for one-quarter of 172 hospitals. Temporal trends suggest reduction in cardiac arrests in both MET and non-MET hospitals |

| Chan et al. 2008 [26] | 18-month-before and 18-month-after study following introduction of RRT | Nursec | Decrease in mean hospital codes (11.2 to 7.5/1,000 admissions) but not significant after adjustment (0.76 (95% CI, 0.57 to 1.0); P = 0.06). Lower rates of non-ICU codes (AOR 0.59 (95% CI, 0.40 to 0.89) versus ICU codes AOR, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.64 to 1.43); P = 0.03 for interaction). No decrease in hospital-wide mortality 3.22% versus 3.09% (AOR, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.81 to 1.11); P = 0.52) |

aComparison data refer to before and after, contemporaneous case control or cluster randomized controlled trial. bYear of publication. cDoctor involved at discretion of nurse team leader. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MET, Medical Emergency Team; OR, odds ratio; RRR, relative risk reduction; RRT, Rapid Response Team.

The interventions that can be provided by a physician-led MET differ substantially to those of a nurse-led RRT, and may expedite transfer to the critical care unit, or the institution of DNR orders. This is particularly the case if the physician team leader has intensive care expertise. Thus, the 'dose' of therapy may differ between institutions according to team composition and expertise. This aspect of the RRT is one of the least studied areas of RRS research. It is also likely that the required MET dose at an individual hospital will reflect the patient case mix, staff ratios and skill mix, and incidence of SAEs. However, outside of Priestly and colleagues' study all publications reporting a decrease in cardiac arrests with the introduction of a RRT [16,18,27-31] described the effect of a physician/intensivist-led team. These observations suggest that an important element of 'dose' might well include not only the number of attendances but the composition of the team. It is clinically plausible that a MET will deliver more intensive medical treatment more rapidly than a RRT without an appropriately trained medical presence. A RRT that is not a MET may significantly decrease the likelihood of a positive outcome. It should be noted that the interpretation of the literature related to nurse-led RRTs is confounded by the graded response and escalation of care associated with some Critical Care Outreach services, particularly in the United Kingdom.

In summary, SAEs are common in hospitalized patients and are often heralded by derangements of vital signs. If the RRT is the major method for reviewing such events, the dose of RRT activation must be sufficient for the frequency and severity of the problem it is intended to treat. In this sense, the RRT is similar to all medical interventions: if it is not given, it does not work. If given at an inadequate dose, it has no discernible effect. If given at a sufficient dose, it displays the type of effectiveness that physiological and clinical plausibility would suggest. All but one of the positive comparative studies of the RRT involve a MET, suggesting that medical presence in the efferent arm treatment may also affect outcomes of RRT review and represent an important component of dose. Studies of RRSs that do not deliver an adequate dose in terms of frequency of intervention and team composition are likely to fail, confound the literature, and may mislead physicians.

Abbreviations

DNR: do not resuscitate; MERIT: Medical Early Response Intervention and Therapy; MET: Medical Emergency Team; RRS: Rapid Response System; RRT: Rapid Response Team; SAE: serious adverse event.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Daryl Jones, Email: Daryl.jones@med.monash.edu.au.

Rinaldo Bellomo, Email: rinaldo.bellomo@med.monash.edu.au.

Michael A DeVita, Email: devitam@upmc.edu.

References

- Mark BA, Harless DW, McCue M, Xu Y. A longitudinal examination of hospital registered nurse staffing and quality of care. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:279–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, Stukel TA. Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:777–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252402.33814.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, Orav EJ, Zeena T, Williams EJ, Howard KM, Weiler PC, Brennan TA. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38:261–271. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent C, Neale G, Woloshynowych M. Adverse events in British hospitals: preliminary retrospective record review. BMJ. 2001;322:517–519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7285.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist MD, Jarmolowski E, Burton PR, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson J. Recognising clinical instability in hospital patients before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care. A pilot study in a tertiary-care hospital. Med J Aust. 1999;171:22–25. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T, Daffurn K, Jacques T, Norman SL, Bishop GF, Simmons G. Antecedents to hospital deaths. Intern Med J. 2001;31:343–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2001.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman KM, Bristow PJ, Chey T, Daffurn K, Jacques T, Norman SL, Bishop GF, Simmons G. Duration of life-threatening antecedents prior to intensive care admission. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:1629–1634. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1496-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts TJ, Brown T, Driscoll P, Hanson J. Pre-hospital cardiac arrest: room for improvement. Resuscitation. 1995;29:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0300-9572(94)00818-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England K, Bion JF. Introduction of medical emergency teams in Australia and New Zealand: a multicentre study. Crit Care. 2008;12:151. doi: 10.1186/cc6902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devita MA, Bellomo R, Hillman K, Kellum J, Rotondi A, Teres D, Auerbach A, Chen WJ, Duncan K, Kenward G, Bell M, Buist M, Chen J, Bion J, Kirby A, Lighthall G, Ovreveit J, Braithwaite RS, Gosbee J, Milbrandt E, Peberdy M, Savitz L, Young L, Harvey M, Galhotra S. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2463–2478. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000235743.38172.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Bates S, Warrillow S, Goldsmith D, Kattula A, Way M, Gutteridge G, Buckmaster J, Bellomo R. Effect of an education programme on the utilization of a medical emergency team in a teaching hospital. Intern Med J. 2006;36:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraida MI, DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Stuart SA, Brooks MM, Simmons RL. Improving the utilization of medical crisis teams (Condition C) at an urban tertiary care hospital. J Crit Care. 2003;18:87–94. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2003.50002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter AD, Cardinal P, Hooper J, Patel R. Medical emergency teams at The Ottawa Hospital: the first two years. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55:223–231. doi: 10.1007/BF03021506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiano N, Young L, Hillman K, Parr M, Jayasinghe S, Baramy LS, Stevenson J, Heath T, Chan C, Claire M, Hanger G. Analysis of Medical Emergency Team calls comparing subjective to "objective" call criteria. Resuscitation. 2008;80:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Bellomo R, Bates S, Warrillow S, Goldsmith D, Hart G, Opdam H, Gutteridge G. Long term effect of a medical emergency team on cardiac arrests in a teaching hospital. Crit Care. 2005;9:R808–815. doi: 10.1186/cc3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Bellomo R, Bates S, Warrillow S, Goldsmith D, Hart G, Opdam H. Patient monitoring and the timing of cardiac arrests and medical emergency team calls in a teaching hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1352–1356. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist M, Harrison J, Abaloz E, Van Dyke S. Six year audit of cardiac arrests and medical emergency team calls in an Australian outer metropolitan teaching hospital. BMJ. 2007;335:1210–1212. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39385.534236.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DA, McIntyre T, Baldwin I, Mercer I, Kattula A, Bellomo R. The medical emergency team and end-of-life care: a pilot study. Crit Care Resusc. 2007;9:151–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist M, Bellomo R. MET: the emergency medical team or the medical education team? Crit Care Resusc. 2004;6:88–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casamento AJ, Dunlop C, Jones DA, Duke G. Improving the documentation of medical emergency team reviews. Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10:29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Opdam H, Egi M, Goldsmith D, Bates S, Gutteridge G, Kattula A, Bellomo R. Long-term effect of a Medical Emergency Team on mortality in a teaching hospital. Resuscitation. 2007;74:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, Bellomo R, Brown D, Doig G, Finfer S, Flabouris A. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2091–2097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66733-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bellomo R, Flabouris A, Hillman K, Finfer S. ;MERIT Study Investigators for the Simpson Centre; ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. The relationship between early emergency team calls and serious adverse events. Crit Care Med. 2008;37:148–53. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181928ce3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, Mozley C, Russell D, Wilson J, Cope J, Hart D, Kay D, Cowley K, Pateraki J. Introducing Critical Care Outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1398–1404. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PS, Khalid A, Longmore LS, Berg RA, Kosiborod M, Spertus JA. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300:2506–2513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharek PJ, Parast LM, Leong K, Coombs J, Earnest K, Sullivan J, Frankel LR, Roth SJ. Effect of a rapid response team on hospital-wide mortality and code rates outside the ICU in a Children's Hospital. JAMA. 2007;298:2267–2274. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibballs J, Kinney S, Duke T, Oakley E, Hennessy M. Reduction of paediatric in-patient cardiac arrest and death with a medical emergency team: preliminary results. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:1148–1152. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.069401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, Buckmaster J, Hart GK, Opdam H, Silvester W, Doolan L, Gutteridge G. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179:283–287. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387–390. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL. Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:251–254. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, Daffurn K, Jacques TC, Norman SL, Bishop GF, Simmons EG. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and intensive care admissions: the effect of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173:236–240. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb125627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, Buckmaster J, Hart G, Opdam H, Silvester W, Doolan L, Gutteridge G. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:916–921. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000119428.02968.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward G, Castle N, Hodgetts T, Shaikh L. Evaluation of a medical emergency team one year after implementation. Resuscitation. 2004;61:257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Egi M, Bellomo R, Goldsmith D. Effect of the medical emergency team on long-term mortality following major surgery. Crit Care. 2007;11:R12. doi: 10.1186/cc5673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, George C, Hart GK, Bellomo R, Martin J. Introduction of Medical Emergency Teams in Australia and New Zealand: a multi-centre study. Crit Care. 2008;12:R46. doi: 10.1186/cc6857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]