Abstract

Cytoplasmic dynein is a complex containing heavy chains (HCs), intermediate chains (ICs), light intermediate chains (LICs), and light chains (LCs). The HCs are responsible for motor activity. The ICs at the tail region of the motor interact with dynactin, which is essential for dynein function. However, functions of other subunits and how they contribute to the assembly of the core complex are not clearly defined. Here, we analyzed in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans functions of the only LIC and two LCs, RobA (Roadblock/LC7) and TctexA (Tctex1) in dynein-mediated nuclear distribution (nud). Whereas the deletion mutant of tctexA did not exhibit an apparent nud mutant phenotype, the deletion mutant of robA exhibited a nud phenotype at an elevated temperature, which is similar to the previously characterized nudG (LC8) deletion mutant. Remarkably, in contrast to the single mutants, the robA and nudG double deletion mutant exhibits a severe nud phenotype at various temperatures. Thus, functions of these two LC classes overlap to some extent, but the presence of both becomes important under specific conditions. The single LIC, however, is essential for dynein function in nuclear distribution. This is evidenced by the identification of the nudN gene as the LIC coding gene, and by the nud phenotype exhibited by the LIC down-regulating mutant, alcA-LIC. Without a functional LIC, the HC-IC association is significantly weakened, and the HCs could no longer accumulate at the microtubule plus end. Thus, the LIC is essential for the assembly of the core complex of dynein in Aspergillus.

Introduction

Cytoplasmic dynein is the major minus end-directed microtubule motor in eukaryotic cells. It plays multiple roles including mitotic regulation and intracellular transport of vesicles/organelles (1, 2). The major form of cytoplasmic dynein, cytoplasmic dynein 1, is a multisubunit complex with a molecular mass greater than 1 MDa. It consists of two heavy chains (HCs,5 ∼500 kDa), intermediate chains (ICs, ∼74 kDa), light intermediate chains (LICs, ∼50–60 kDa), and light chains (LCs, ∼8 to 22 kDa) (3–5). The heavy chain (HC), which has motor activity, contains an N-terminal stem region (or tail) and a C-terminal motor unit with six AAA (ATPase associated with cellular activities) domains that are organized into a ring-like structure (6–8). The tail of HC is involved in dimerization and also contains binding sites for the IC and LIC (9). The IC directly binds the p150 subunit of the dynactin complex, which is essential for dynein function in vivo (10–14). The IC N-terminal region also contains binding sites for all three LCs, Tctex1, LC8, and LC7/Roadblock (Rob1) (5, 15). These non-HC subunits are implicated in targeting the motor to various cargoes, and they may also be regulated to achieve cargo release from the dynein complex (10, 16–20). However, whether these subunits participate in the assembly of the core complex of cytoplasmic dynein remains an open question to be addressed in various experimental systems.

In filamentous fungi and in the budding yeast, multiple proteins in the dynein pathway have been identified by genetic studies on nuclear distribution and/or spindle orientation (21–23). However, except for the LC8 light chain that was identified as a protein in the dynein pathway in Aspergillus nidulans (24, 25) and also studied in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (26), functions of the other LCs are in general not clear in these organisms. In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, the Tctex1 homolog has been reported to function with the dynein heavy chain in prophase nuclear migration during meiosis and achiasmate segregation (27, 28). However, Tctex1 in Drosophila is not essential for dynein function during development (29), and it has dynein-independent functions in higher eukaryotes (30, 31).

The function of dynein LIC was first studied in Caenorhabditis elegans, and it was shown that LIC is important for a variety of mitotic functions of dynein (32). However, the role of LIC in the assembly of the core dynein complex has been controversial. In mammalian cells, there are two LICs for cytoplasmic dyein 1, LIC1 and LIC2 (4, 9), and depleting either one of them in Hela cells does not seem to significantly affect the stability of dynein components (33, 34). In Drosophila and lower eukaryotes, only one LIC gene for the cytoplasmic dynein 1 is present. The only LIC for cytoplasmic dynein 1 in Drosophila is required for the stability of both the HCs and ICs, suggesting that the LIC may be important for the formation and the stability of the dynein complex (35). In S. cerevisiae, the LIC is required for dynein function in spindle orientation (36). Whereas it is implicated in offloading dynein from the microtubule-plus end to the cortex, it is clearly not required for the stability of the dynein complex (36). The reason behind this discrepancy is unclear, and it would be useful to investigate the role of LIC in other organisms.

In this study, we identified the LIC and the Tctex1 and Roadblock LCs in the A. nidulans genome and studied their functions in the context of the well-established role of dynein in nuclear distribution. Our results indicate that the Tctex1 homolog, TctexA, is not essential for dynein function in nuclear distribution, and the Roadblock homolog, RobA, is important for proper nuclear distribution at an elevated temperature of 42 °C, similar to the previously characterized NUDG/LC8 (25). Remarkably, the robA/nudG double deletion mutant shows a severe nud phenotype at various temperatures. These results suggest that the RobA and NUDG/LC8 LCs play overlapping roles in regulating dynein-mediated nuclear distribution, and the presence of both is only important at an elevated temperature. The single LIC, however, is essential for dynein function in nuclear distribution. In this study, we have identified the gene of the previously isolated nudN locus (37), which encodes the only LIC in A. nidulans. In addition, an LIC down-regulating mutant, alcA-LIC, exhibited a clear nud phenotype. We also provided the first biochemical evidence that the LIC is essential for the proper interaction between the HC and the IC.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

A. nidulans Strains and Growth Media

A. nidulans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Growth media and growth conditions were as described previously (38).

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this work

All strains have the veA1 marker.

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SJ002 | pyrG89 | S. James |

| GR5 | pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | G. S. May |

| TNO2A3 | ΔnkuA-argB; pyrG89; pyroA4 | (40) |

| JZ11 or S-IC | S-tagged-nudI; pyrG89; pabaA1, yA1 | (42) |

| LZ26 | GFP-nudA (or GFP-HC); S-tagged-nudI (or S-IC); nkuA::argB; pyroA4; pyrG89, yA1 | (42) |

| LBA33 | ΔnudG-pyrG; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | (25) |

| ΔnudG/S-IC | ΔnudG-pyrG; S-tagged-nudI; pyrG89 | This work |

| ΔtctexA | ΔtctexA-pyrG; ΔnkuA-argB; pyrG89; pyroA4 | This work |

| ΔrobA | ΔrobA-pyrG; ΔnkuA-argB; pyrG89; pyroA4 | This work |

| SL230 | ΔrobA-pyrG; pabaA1; yA1; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

| SL231 | ΔrobA-pyrG; S-tagged-nudI; pyroA4; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

| SL233 | ΔtctexA-pyrG; pabaA1; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

| SL239–240 | ΔrobA-pyrG; GFP-nudA; S-tagged-nudI; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

| WX117 | nudN117; pyrG89 | (37) |

| alcA-LIC | alcA-GFP-LIC-pyr4; GFP-nudA; S-tagged-nudI; nkuA::argB; pyroA4; pyrG89, yA1 | This work |

| WX825/S-IC | nudR825; S-tagged-nudI | This work |

| JZ310–314 | alcA-GFP-robA-pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | This work |

| JZ315–317 | alcA-GFP-robA-pyr4; ΔnkuA-argB; pyrG89; pyroA4 | This work |

| JZ318–322 | alcA-GFP-tctexA-pyr4; pyrG89; pyroA4; wA3 | This work |

| JZ323–329 | alcA-GFP-tctexA-pyr4; ΔnkuA-argB; pyrG89; pyroA4 | This work |

| ΔrobA/ΔnudG-8 | ΔrobA-pyrG; ΔnudG-pyrG; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89; possibly yA1; possibly wA3 | This work |

| ΔtctexA/ΔnudG-22 | ΔtctexA-pyrG; ΔnudG-pyrG; pabaA1; wA3; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

| ΔtctexA/ΔrobA-15 | ΔtctexA-pyrG; ΔrobA-pyrG; possibly ΔnkuA-argB; possibly pyrG89 | This work |

Construction of the ΔrobA and ΔtctexA Strains

To create deletion mutants, we first identified sequences upstream and downstream of the respective genes from the A. nidulans genome. To create a robA deletion (ΔrobA) construct, we used the following strategy. Fragment 1, which is the 2.1-kb genomic fragment upstream of the RobA-coding region (ends at the 25th nucleotide before the start codon ATG), was amplified from the genomic DNA with two primers, 5′-TACCTGCAGGAACCGCAAGATTCACAG-3′ and 5′-ACTCTGCAGTCGAAGTAAGGCACTTTG-3′ (both PstI sites are underlined), and was cloned into the PstI site of the pXX1 plasmid containing the selective marker pyrG (39). We named the resultant plasmid 1-pxx1. Fragment 2, which is the 2-kb genomic fragment downstream of the RobA-coding region (starts from the 10th nucleotide after the stop codon) was amplified from the genomic DNA with two primers, 5′-AACGGATCCTAGCCTAATGTGGATGACACC-3′ and 5′-TCAGCGGCCGCACGAGATGTGCAGTTCCTAAG-3′ (the BamHI and NotI sites are underlined, respectively), and was cloned into the BamHI and NotI sites of the 1-pxx1 plasmid. The resultant ΔrobA construct contains the pyrG selective marker flanked at each side by fragments 1 and 2.

Construction of tctexA deletion construct was done using a similar strategy as described above. Specifically, fragment 1, which is the 1.9-kb genomic fragment upstream of the TctexA-coding region (ends at the 10th nucleotide before the start codon ATG), was amplified from the genomic DNA with two primers, 5′-TACCTGCAGACTACTCGGAGCCTCGCTG-3′ and 5′-ACTCTGCAGTAAATGCGCGAAAGGCTTGG-3′ (both PstI sites are underlined), and was cloned into the PstI site of the pXX1 plasmid containing the selective marker pyrG, and the resultant plasmid was named 1-pxx1-tctexA. Fragment 2, which is the 2-kb genomic fragment downstream of the TctexA-coding region (starts at the 28th nucleotide after the stop codon) was amplified from the genomic DNA with two primers, 5′-AACACTAGTAACAACTGATATACCATCGTG-3′ and 5′-TCAGCGGCCGCACATTTGCTACGATGTTACG-3′ (the SpeI and NotI sites are underlined, respectively), and was cloned into the SpeI and NotI sites of the 1-pxx1-tctexA plasmid. The resulting ΔtctexA construct contains the pyrG selective marker flanked at each side by fragments 1 and 2 (Fig. 1).

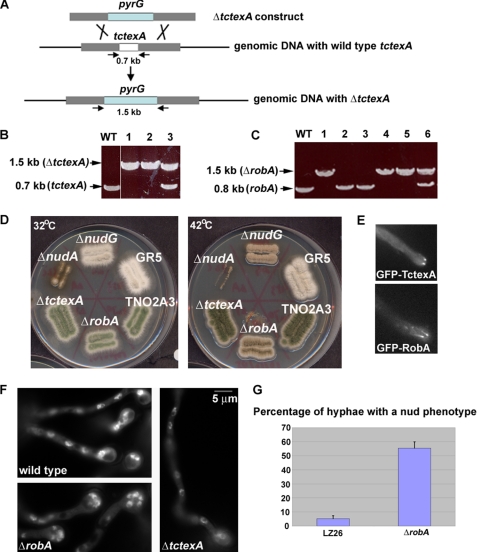

FIGURE 1.

Construction and phenotypic analyses of the ΔtctexA and ΔrobA mutants of dynein LCs. A, diagram showing the strategy of making the ΔtctexA mutant (a similar strategy was used to make the ΔrobA mutant). Arrows indicate positions of primers used in PCR reactions to verify the homologous recombination events that occur in the tctexA locus. B, DNA gel showing the expected PCR product amplified from the ΔtctexA locus. Note that the primers amplified a 0.7-kb fragment in the WT cell, but a 1.5-kb fragment in ΔtctexA cells (lanes 1 and 2) because of the deletion of the tctexA gene (0.7 kb) and the insertion of the pyrG gene. Lane 3 showing both fragments represents a transformant in which the ΔtctexA construct integrated into the genome but did not result in deletion of the tctexA gene. C, DNA gel showing the expected PCR product amplified from the ΔrobA locus. Note that the primers amplified a 0.8-kb fragment in WT cells, but a 1.5-kb fragment in ΔrobA cells because of the deletion of the robA gene (0.8 kb) and the insertion of the pyrG gene (lanes 1, 4, and 5). Lane 6 with both fragments represents a transformant in which the ΔrobA construct integrated into the genome but there was no deletion of the robA gene. D, growth phenotypes of the ΔtctexA and ΔrobA mutants at 32 °C (left) and 42 °C (right) in comparison to that of wild type, ΔnudA(HC), and ΔnudG(LC8). Two wild-type strains, GR5 (the parent strain of ΔnudG) and TNO2A3 (the parent strain of ΔtctexA and ΔrobA), were used as controls. Strains were grown on YUU plates for 2 days. Note that while the ΔtctexA mutant showed no apparent growth defect, the ΔrobA mutant showed a slow growth phenotype at 42 °C, which is similar to ΔnudG, but is much milder than that exhibited by ΔnudA. E, localization of GFP-TctexA and GFP-RobA fusion proteins. Note that they form comet-like structures, representing their accumulation at microtubule-plus ends (46). F, DAPI staining showing that the ΔRobA mutant, but not the ΔtctexA mutant, exhibited a nud phenotype after a 7.5-h incubation in YUU liquid medium at 42 °C. Bar, 5 μm. G, percentage of cells showing the nud phenotype (defined by the presence of a cluster of four or more nuclei) after an overnight incubation at 42 °C. The LZ26 strain with S-IC and GFP-NUDA was used as a control because it has a similar background to the ΔrobA strain used for this particular experiment (SL239). Mean and S.D. values were determined from three experiments. For every experiment, about 150 hyphae were counted for each strain.

The ΔrobA and the ΔtctexA constructs were both linearized by NotI digestion and transformed into a wild-type A. nidulans strain containing the ΔnkuA mutation that results in a significant increase in the percentage of homologous integration events (40). Genomic DNAs from the transformants were subjected to PCR and Southern blot analysis. A ΔrobA and a ΔtctexA strain that showed site-specific integrations to the RobA and TctexA loci that resulted in the deletion of the respective genes were used for further studies (Fig. 1).

Construction of Strains Containing GFP-TctexA and GFP- RobA

To make a GFP-Tctex fusion, we performed polymerase chain reactions on A. nidulans genomic DNA to amplify a 1.7-kb fragment containing the TctexA-coding region plus a 1-kb downstream region with the following two primers: Tcalc5 (5′-AAGCGGCCGCTGGCTGTCGAGACCTCACCC-3′) and Tcalc3 (5′-AACCCGGGCATATCGTTATCGACGTG-3′) (the NotI and SmaI sites are underlined.). This fragment was digested by NotI and SmaI and ligated into the corresponding sites of the LB01 vector that contain GFP downstream of the alcA promoter (41). The resultant plasmid containing the alcA-driven GFP-tctexA fusion was transformed into the GR5 strain and the TNO2A3 strain, and multiple transformants were observed using fluorescence microscopy. The strains containing GFP-RobA were made in the same fashion except that two different primers, robalc5 (5′-AAGCGGCCGCTGGCCAACTCGACCTCAGTAC-3′) and robalc3 (5′-AACCCGGGTTCCCCGCGGTGAGAACTG-3′) were used to amplify a 1.8-kb fragment of the RobA-coding region plus the 1-kb downstream region.

Construction of Double LC Mutants

Double mutants of ΔtctexA/ΔrobA, ΔrobA/ΔnudG, and ΔtctexA/ΔnudG were made by genetic crosses. Selection of the specific double mutants was based on the colony phenotype of the ΔnudG and ΔrobA mutants at 42 °C combined with PCR analyses of the ΔtctexA and ΔrobA loci. Primers used for checking the ΔtctexA locus are pyrG-STOP (5′-GTGTGAGTGGAAATGTGTAAC-3′) and Tcalc3 (5′-AACCCGGGCATATCGTTATCGACGTG-3′). Primers for checking the ΔrobA locus are pyrG-STOP and robalc3 (5′-AACCCGGGTTCCCCGCGGTGAGAACTG-3′).

Complementation of the nudN117 Mutation with Genomic DNA Encoding the LIC

Two primers were used to amplify a 2.5-kb genomic fragment of LIC that covers the sequences including the entire reading frame. The primers are: 5′-GCCTCTGAATCTTGAGTC-3′ and 5′-GCGATGCTGAACTTGTTG-3′. The 2.5-kb PCR product was transformed into the nud mutants whose genes had not been identified (37). An autoreplicating plasmid, pAid, that carried the selective marker pyr4 was used as a co-transforming plasmid (37). Among the tested mutants including nudJ7, nudJ707, nudL43, nudN117, nudP502, and nudR825, the DNA encoding the LIC homolog only rescued the nudN117 mutant. To further confirm that the fragment has repaired the nudN117 mutation, we first incubated the transformants on YUU to allow the loss of pAid (37), and then we crossed the transformant with a wild-type strain. From this cross, we found no nud progeny out of about 500 progeny, indicating that the LIC coding gene repaired the nud117 mutation.

Construction of a Conditional Null Mutant of LIC

We made a conditional null mutant of LIC using a method similar to what has been previously described (38, 39). The N-terminal LIC fragment of ∼0.7 kb was obtained from A. nidulans genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction using the following two primers: LIC5 (5′-AAGCGGCCGCTGTCTACGTCAAAAAGATCC-3′) and LIC3 (5′-AACCCGGGTTCTTCCGCTCTCTCCACTG-3′) (the NotI and SmaI sites are underlined). The 0.7-kb fragment was digested by NotI and SmaI, and ligated into the corresponding sites of the LB01 vector (41). The resultant plasmid was transformed into the LZ26 strain containing GFP-nudA (dynein HC) and S-tagged IC (42). In the expected alcA-LIC strain, the full-length fusion gene is under the control of the regulatable promoter alcA, which can be shut off by glucose but can be induced by glycerol to express a downstream gene at a moderate level. Transformants that show a nud phenotype on YUU plates were subjected to Southern blot analysis. The alcA-LIC strain that showed a single site-specific integration to the LIC gene locus was used for further studies on the function of LIC (Fig. 5).

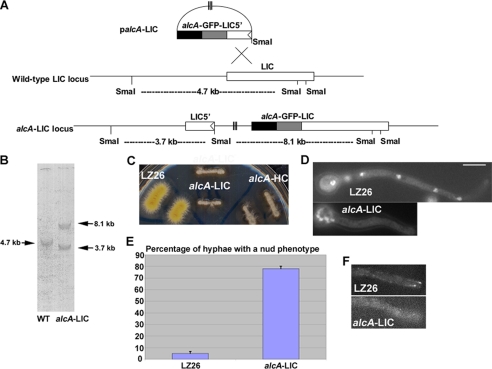

FIGURE 5.

Construction and phenotypic analyses of a conditional null LIC mutant. A, diagram showing the strategy of making the alcA-LIC mutant. B, Southern blot showing the site-specific integration event. C, growth phenotype of the alcA-LIC mutant on a YUU plate (YUU with its contained glucose is used as a repressive condition to shut down the expression of the alcA promoter). Note that the alcA-LIC mutant exhibited a severe growth defect similar to that of the alcA-HC mutant. D, alcA-LIC mutant shows a dramatic nuclear distribution defect after being incubated in YUU liquid medium at 32 °C overnight. LZ26 was used as a wild-type control because it is the parental strain of the alcA-LIC mutant. Bar, 5 μm. E, percentage of cells showing the nud phenotype (defined by the presence of a cluster of four or more nuclei) after an overnight incubation at 32 °C. Mean and S.D. values were determined from three experiments. For every experiment, about 150 hyphae were counted for each strain. F, in the alcA-LIC cells, the bright comet-like structures at the hyphal tip representing GFP-HC microtubule-plus end accumulation in a wild-type control (LZ26) could no longer be observed. The GFP-nudA (HC) fusion gene is driven by the nudA endogenous promoter, and cells were grown on minimal glucose medium overnight at 32 °C to shut off the expression of the alcA-driven LIC.

A. nidulans Dynein Isolation and Analyses

A. nidulans protein extract was obtained from an overnight culture of 1 liter using the liquid nitrogen grinding method for breaking the hyphae, which was similar to what has been described previously (43), except that the protein isolation buffer contains 25 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 0.4% Triton X-100, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma). The construction of an S-tagged dynein intermediate chain strain (S-IC) and the method for dynein purification were described previously (42). For purification of A. nidulans dynein from S-IC strains, about 30 ml of a protein extract (about 10 mg/ml) was incubated for a half-hour at room temperature with 0.5 ml of S-protein beads (Novagen, Inc. Madison, WI). The beads were repeatedly washed with the same buffer used for protein isolation except that no detergent was added. Finally, the beads were boiled in the protein-loading buffer, and the proteins were subjected to Western analyses. Affinity-purified anti-HC, anti-IC, and anti-p150 antibodies were used as previously described (38, 39).

Image Acquisition

Cells were grown in ΔTC3 culture dishes (Bioptechs) in 1.5 ml of MM + glucose (or glycerol) + supplement medium at 32 °C or 42 °C overnight. Images were captured using an Olympus IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope (with a ×100 objective) with a PCO/Cooke Corporation Sensicam QE cooled CCD camera. The IPLab software was used for image acquisition and analysis.

RESULTS

Characterizations of the Tctex1 and Roadblock Homologs in A. nidulans

In the A. nidulans genome, there is one gene encoding the Tctex1 homolog (An1333) and one gene encoding the Roadblock homolog (An8669). These genes were identified by using the respective mouse homolog as a query for a BLAST search against the A. nidulans data base. The Tctex1 homolog, TctexA (hypothetical protein An1333; NCBI accession number: XP_658937), is predicted to be a protein with 141 amino acids (15 kDa). Its protein sequence showed 28% identity and 44% similarity over a 124 amino acid long region (from amino acids 4 to 127) to the mouse Tctex1 (XP_033368). The Roadblock homolog, RobA (hypothetical protein An8669; NCBI accession number: XP_681938) is a 241 amino acid protein (25 kDa). It is significantly bigger than the mouse homolog Roadblock/LC7 chain B (GenBankTM locus name: 1Y40_B) (44) that contains only 104 amino acids, but similar in size to its Neurospora crassa homolog (NCBI accession number: XP_964912) that has 212 amino acids. Interestingly, the RobA homology to its mouse homolog is limited to the C terminus. A 32-amino acid C-terminal region of RobA (from amino acids 187 to 218) showed 40% identity and 78% similarity to the C-terminal region of the mouse Roadblock/LC7 chain B.

Deletion mutants of tctexA and robA were created. On plates, ΔtctexA and ΔrobA mutants do not show any obvious growth phenotype at 32 °C. However, the ΔrobA mutant exhibited reduced colony size at 42°C, although it looked much healthier than the ΔnudA dynein heavy deletion mutant (Fig. 1). DAPI staining of ΔrobA cells grown at 42 °C showed that many ΔrobA cells exhibited nuclear clustering at the spore end (Fig. 1), similar to the other nud mutants in the dynein pathway (22). However, in the ΔtctexA mutant, nuclear distribution is apparently normal (Fig. 1), indicating that TctexA is dispensable for dynein function in nuclear distribution.

Because the ΔtctexA mutant did not exhibit a nud phenotype at any tested temperatures, one concern was that TctexA might not be associated with the dynein complex. In A. nidulans, GFP-labeled HC and IC molecules can be seen as comet-like structures near the hyphal tip, representing their accumulation at the dynamic microtubule-plus end (43, 46). This localization is important for spindle positioning in yeast and for dynein-mediated retrograde endosome transport in filamentous fungi (47–52). We made a GFP-TctexA fusion under the control of the alcA promoter and observed its localization in live cells. As expected for a component of the dynein complex, GFP-TctexA formed the same dynamic comet-like structures as GFP-HC and GFP-IC (Fig. 1 and Refs. 43, 46), strongly suggesting that TctexA is associated with the dynein complex in A. nidulans. A similar study was also done for the RobA protein. Although the ΔrobA mutant does exhibit a nud phenotype at 42 °C, the predicted RobA protein size is significantly greater than that of its mouse homolog, and the homology between RobA and its mouse homolog is only limited at the RobA C terminus, raising the concern of whether it is an actual ortholog of the mammalian LC. However, we found that the GFP-RobA fusion, in which the GFP is inserted in-frame at the N terminus of RobA, forms typical comet-like structures just like GFP-HC and GFP-IC, strongly suggesting that RobA is also associated with the dynein complex in A. nidulans.

Our data suggest that RobA is important for dynein function at 42 °C. A previous study in A. nidulans on the NUDG/LC8 light chain demonstrates that this light chain is only critical for dynein function at higher temperatures (25). Thus, it is likely that the dynein complex without one of these light chains can still function at certain physiological conditions, but is not fully functional in other physiological conditions.

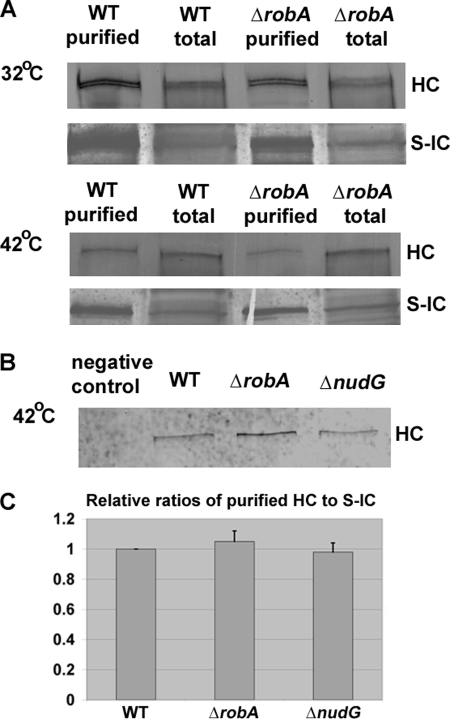

Because both the LC8 and RobA LCs bind to the N-terminal region of the IC (15), it is possible that they affect dynein function at a high temperature by affecting either the ability of the IC to dimerize or the ability of the IC to interact with the HC. A recent study has suggested that IC dimerization does not require the LCs (45). Thus, we determined whether HC-IC association is affected by the deletion of these LCs. We have previously made a strain containing a functional S-tagged dynein IC (S-IC), and the S-IC is able to pull down the HC proteins (42). In this work, we introduced the S-IC into the ΔnudG and ΔrobA backgrounds by genetic crosses and examined the HC-IC association at 42 °C. Interestingly, these LC mutants did not exhibit any apparent defects in IC-HC interaction (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

HC-IC association in the ΔrobA mutant and the ΔnudG(LC8) mutant at 42 °C. A, association between HC and IC is not apparently disrupted in ΔrobA cells as S-IC was able to pull down HC at both 32 °C (top panel) and 42 °C (middle panel), similar to WT cells. B, S-IC was also able to pull down HC in the ΔnudG mutant grown at 42 °C (bottom panel). In this experiment, the GR5 strain without S-IC was used as a negative control. C, quantitative analysis on the ratios of HC to S-IC after purification. Values were all relative to the wild-type values, which were set at 1. Mean and S.D. values were determined from three independent experiments. Note that there is no significant difference between the mean value in either mutant and that in the wild type at a p value of 0.05.

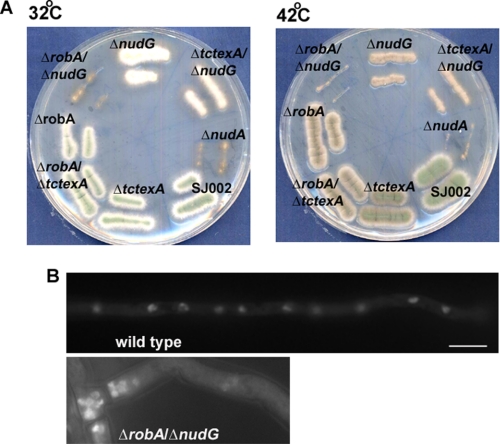

Whether and how different classes of LCs may play overlapping roles in regulating the ICs will need to be determined in the future. To this end, we have made three kinds of LC double deletion mutants, ΔtctexA/ΔrobA, ΔtctexA/ΔnudG, and ΔrobA/ΔnudG. The ΔtctexA/ΔrobA double mutant appeared the same as the ΔrobA single mutant, and the ΔtctexA/ΔnudG double mutant exhibited a slightly worse colony growth defect than the ΔnudG single mutant. But remarkably, the ΔrobA/ΔnudG double mutant exhibited a severe nud mutant colony phenotype similar to that exhibited by ΔnudA (the HC deletion mutant) at 42, 37, and even 32 °C, a temperature at which the respective single mutants did not exhibit any obvious colony phenotype (Fig. 3). DAPI staining showed that it exhibited a typical nud phenotype at 32 °C (Fig. 3). Thus the functions of RobA and NUDG/LC8 overlap to some extent.

FIGURE 3.

Phenotypic analyses of the ΔrobA/ΔnudG(LC8) double mutant. A, colony phenotypes of the LC double mutants at 32 °C and 42 °C. Note that the ΔrobA/ΔnudG double mutant produced a colony phenotype nearly identical to that exhibited by ΔnudA (dynein HC-null). Strains were grown on YUU plates for 2 days. B, DAPI staining showing the nuclear distribution phenotype of the ΔrobA/ΔnudG mutant at 32 °C. The cells were grown at 32 °C overnight. Bar, 5 μm.

The LIC Is Essential for the Formation of the Core Complex of Dynein

The A. nidulans LIC gene (AN4664; NCBI accession number: XP_662268) was found from the annotated genome by using the mouse LIC1 and LIC2 as queries. It encodes a 505 amino acid protein with a predicted molecular mass of 56 kDa. It shows significant sequence similarity to both the Lic1 (NP_666341 or AAH23347) and Lic2 (AAH58645 or Q6PDL0) of mouse cytoplasmic dynein 1. From amino acids 18–334, the identity and similarity to both the mouse LICs are about 27 and 45%, respectively.

During an effort to characterize several nud mutants whose defective gene products had not been previously identified (37), we found that the DNA fragment containing the coding region of the A. nidulans LIC completely rescued the nud phenotype of the nudN117 mutant (Fig. 4), and further genetic analysis confirmed that it is the gene for nudN (more details under “Experimental Procedures”).

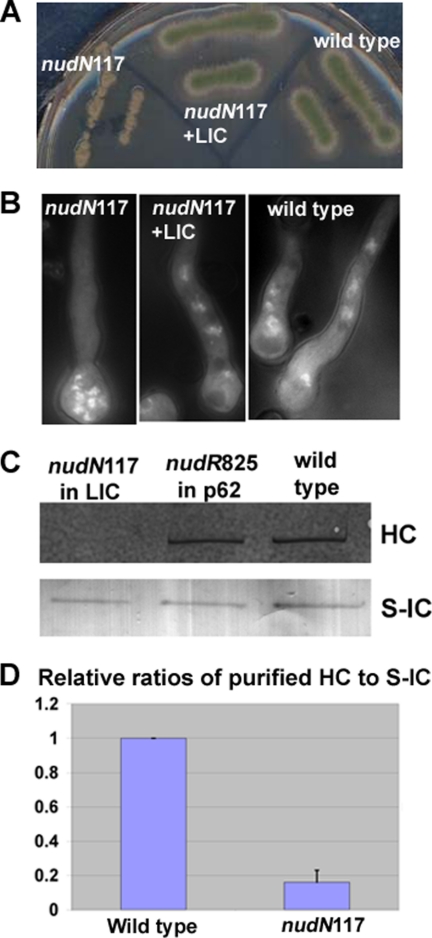

FIGURE 4.

Rescue of the nudN117 mutant phenotype by the LIC-coding gene and a biochemical analysis of the nudN117 mutant of LIC. A, colony phenotypes of the nudN117 mutant, a nudN117 strain rescued by the LIC gene and a wild-type control strain. The strains were grown on a YUU plate at 42 °C for 2 days. B, DAPI staining showing that the LIC gene allowed normal nuclear distribution in the nudN117 mutant. Strains were grown in YUU liquid medium overnight at 42 °C. C, Western blot showing that the HC proteins could no longer be pulled down by the S-IC in the nudN117 mutant grown at 42 °C. WT cells and nudR825, a ts mutant of p62 of the dynactin complex (38), were used as controls. D, quantitative analysis on the ratios of HC to S-IC after purification. Values were all relative to wild-type values, which were set at 1. Mean and S.D. values were determined from four independent experiments. Note that the mean value of the nudN117 mutant is significantly different from that of the wild type (p < 0.001).

The LIC has a profound effect on the integrity of the dynein complex. This was first noticed when we analyzed the nudN117 mutant. In the S-IC/nudN117 strain, the amount of dynein HC pulled down by the S-IC was dramatically decreased (Fig. 4).

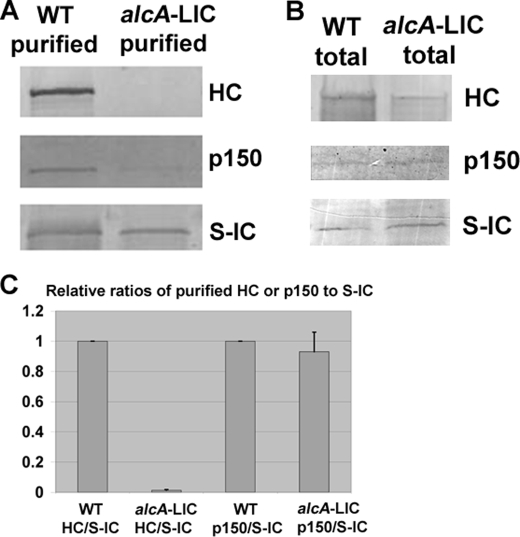

To confirm the notion that the LIC is important for dynein complex integrity in A. nidulans, we made the alcA-LIC strain in which the expression of the LIC gene is shut off by glucose (Fig. 5). This alcA-LIC strain was made in the background of LZ26 that contains S-IC and GFP-HC under the control of its endogenous promoter (42). Thus, the effect of LIC depletion on dynein HC localization and dynein complex integrity could be directly determined by comparing the alcA-LIC strain with LZ26. GFP-labeled HC molecules can be seen as bright comet-like structures near the hyphal tip, representing their accumulation at the dynamic microtubule-plus end (46). Upon depletion of the LIC, the bright comet-like structures could no longer be detected, suggesting that LIC is essential for dynein accumulation at the microtubule-plus end (Fig. 5). Consistent with the observation we made with the nudN117 mutant, integrity of the dynein HC-IC core complex was significantly affected in the alcA-LIC mutant. After growing the cells in the repressive glucose medium for 15 h at 32 °C, the amount of S-IC proteins that are eluted from the S-agarose column was slightly reduced. It was also obvious that less p150 proteins of the dynactin complex were pulled down, which is consistent with the notion that IC binds to p150 directly (10–12). Significantly, the HCs pulled down by the S-ICs could hardly be detectable (Fig. 6). This happens despite that the level of HCs in total extract was only slightly decreased in the alcA-LIC sample compared with that of the wild-type control (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the LIC is essential for the HC-IC interaction.

FIGURE 6.

The alcA-LIC mutant cells grown on the repressive medium YUU exhibit a defect in HC-IC association. A, Western blots showing a typical purification result. In this experiment, cells were grown for 15 h at 32 °C, and similar amounts of total proteins from the WT and the alcA-LIC strains were used for affinity purification. Note that the amount of p150 pulled down by S-IC is decreased in the alcA-LIC mutant, and much more dramatically, HC was no longer detected after S-IC-based purification. B, Western blots showing that the levels of p150 and S-IC were not significantly decreased in total cell extract upon growing the cells on YUU for 15 h. The level of the HC was only slightly decreased under a similar condition. This is in sharp contrast to the pull-down data showing that the HC could no longer be detected in alcA-LIC cells even when the signal for the pulled-down HC from WT cells was very strong. C, quantitative analysis on the ratios of HC to S-IC or p150 to S-IC after purification. Values were all relative to the wild-type values, which were set at 1. Mean and S.D. values were determined from four independent experiments. Note that the mean value of HC/S-IC in the alcA-LIC mutant is significantly different from that in the wild type (p < 0.001). However, the mean values of p150/S-IC are not significantly different at a p value of 0.05.

DISCUSSION

TctexA Is Not Essential for Dynein-mediated Nuclear Distribution

The function of the Tctex1 LCs are involved in both dynein-dependent and dynein-independent functions in different organisms. For example, in mammalian photoreceptors, Tetex1 interacts with the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of rhodopsin, which mediates translocation of rhodopsin-bearing vesicles along microtubules driven by dynein (16). However, in hippocampal neurons, Tctex1 plays a dynein-independent role in modulating actin dynamics to promote neurite extension (30). In S. pombe, this LC participates in dynein function during meiosis (27, 28). But studies from Drosophila suggest that although this LC is a component of the dynein complex, it is not essential for dynein function during development (29). In filamentous fungi, dynein has a well-established role in nuclear distribution (21, 23). However, our current study indicates that although TctexA localizes to the microtubule-plus end just like other proteins in the dynein pathway, the Tctex1 homolog in A. nidulans is not essential for dynein-mediated nuclear distribution. Thus, while Tctex1 may be involved in targeting dynein to specific cargoes, it does not seem to be required for the core activity of dynein. In A. nidulans, the deletion mutant of this LC does not exhibit any obvious colony growth phenotype, suggesting that it is not required for any cellular processes essential for hyphal growth or conidiation (asexual spore production). However, introducing the ΔtctexA allele into the ΔnudG background does seem to mildly affect colony morphology of the ΔnudG single mutant (Fig. 3), suggesting that TctexA may possibly play a minor role in supporting dynein function.

RobA and NUDG/LC8 May Play Overlapping Roles in Regulating Dynein Function but the Presence of Both Classes Becomes Crucial at an Elevated Temperature

In this study, we found that the deletion mutant of RobA, the roadblock homolog, exhibited a nuclear distribution phenotype at an elevated temperature of 42 °C. This phenotype is very similar to that of the NUDG/LC8 subunit described previously (25). These results suggest that these LCs are not essential for the core function of dynein under normal conditions, but may be required for maintaining dynein function at extreme environmental conditions. In both deletion mutants grown at 42 °C, however, HC-IC association is apparently normal because the S-IC is able to pull down nearly normal amounts of the HC. Thus, how they are required for dynein function at a higher temperature will still need to be addressed in the future. It has been found that the microtubule-plus end accumulation of dynein HC is abolished by the loss of NUDG/LC8 at 42 °C (25), and the mechanism of this effect needs to be further studied. One important current finding is that the RobA and NUDG/LC8 double deletion mutant exhibits a severe nud phenotype at temperatures that allow the single mutants to grow normally. Thus, RobA and NUDG/LC8 may play overlapping roles in regulating dynein function, and the presence of one class can compensate for the absence of the other at lower temperatures. How they affect dynein function and why the requirement for the presence of both classes is higher at a higher temperature are interesting topics for future studies. Specifically, whether they affect the efficiency of IC dimerization (56) or dynactin binding (10) will need to be determined.

The LIC Is Essential for HC-IC Association

We found that the LIC, but not the LCs, is essential for the assembly and/or the stability of the core dynein complex containing HCs and ICs. In addition, the microtubule-plus end accumulation of the HCs is significantly diminished in LIC-depleted cells (Fig. 5). This is most likely caused by the effect of LIC depletion on HC's ability to associate with the IC, as we have shown previously that the microtubule-plus end accumulation of dynein HC requires a functional IC (43). Our current results on the critical role of LIC in dynein complex assembly and localization are in sharp contrast to the results obtained in S. cerevisiae, where the IC but not the LIC is required for plus end accumulation of dynein (36). It is likely that LIC homologs play evolutionarily diverse roles in different organisms or cell types. In Hela cells, although the two LICs of cytoplasmic dynein 1 may be in different dynein complexes involved in different functions (34), depleting one of them does not seem to affect the stability of the dynein complex significantly (33, 34). In Drosophila, however, the only LIC of cytoplasmic dynein 1 is important for the stability of both the HCs and ICs (35).

Our current study provides the first evidence in a filamentous fungus that the LIC is clearly involved in HC-IC interaction. It would be useful to further test this notion in higher eukaryotic cells. Our data also suggest that LIC depletion has a more significant effect on HC-IC interaction than on IC-p150 interaction (Fig. 6). Thus, we believe that LIC depletion more directly affects the HC than the IC. This is consistent with the observation that LIC interacts directly with the HC, and that LIC and IC bind to adjacent but different sites of the HC N-terminal tail region (9). An earlier in vitro study also showed that upon treatment with potassium iodide, the cytoplasmic dynein complex disassembles into two subcomplexes, HC+LIC, and IC (53). Thus, it is most likely that removing the LIC primarily affects HC conformation and its ability to properly associate with the IC. We have previously reported that GFP-IC proteins are not stable in a ts mutant of nudA (HC) grown at the restrictive temperature; a condition that significantly destabilizes the HC proteins (43). This is consistent with results in mammalian cells where RNAi of the HCs significantly reduces the level of the ICs (54, 55). However, in our current study, although the level of HCs pulled down by the S-IC is dramatically decreased, the level of S-ICs is much less severely affected. Together, these results suggest that depletion of the LIC may not cause a complete separation of the HC and IC in the cell, at least at the time point of our assay, but it significantly weakens HC-IC interaction so that even our mild purification conditions have allowed us to detect this defect.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Oakley and M. Hynes for the nkuA deletion strain, B. Liu for the nudG/LC8 deletion strain, L. Zhuang for the GFP-HC/S-IC strain, and L. Wang for the antibody against p150. We thank Drs. H. Zhu, B. Liu, and M. Plamann for help and discussions on the LC work. We thank the reviewers for helpful suggestions, especially the suggestion to make LC double mutants.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM069527 (to X. X.). This work was also supported by a USUHS intramural grant (to X. X.), a grant from CNP (Comprehensive Neuroscience Program)-DOD (to X. X.), and the USU Center for Health Disparities (to S. M.).

- HC

- heavy chain

- IC

- intermediate chain

- LIC

- light intermediate chain

- LC

- light chain

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- nud

- nuclear distribution

- WT

- wild type

- AAA

- ATPase associated with cellular activities

- S-IC

- S-tagged dynein intermediate chain strain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karki S., Holzbaur E. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11, 45–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vale R. D. (2003) Cell 112, 467–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.King S. M. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1496, 60–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfister K. K., Fisher E. M., Gibbons I. R., Hays T. S., Holzbaur E. L., McIntosh J. R., Porter M. E., Schroer T. A., Vaughan K. T., Witman G. B., King S. M., Vallee R. B. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 411–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfister K. K., Shah P. R., Hummerich H., Russ A., Cotton J., Annuar A. A., King S. M., Fisher E. M. (2006) PLoS Genet 2, e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samsó M., Radermacher M., Frank J., Koonce M. P. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 276, 927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgess S. A., Walker M. L., Sakakibara H., Knight P. J., Oiwa K. (2003) Nature 421, 715–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts A. J., Numata N., Walker M. L., Kato Y. S., Malkova B., Kon T., Ohkura R., Arisaka F., Knight P. J., Sutoh K., Burgess S. A. (2009) Cell 136, 485–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tynan S. H., Gee M. A., Vallee R. B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32769–32774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroer T. A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 759–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karki S., Holzbaur E. L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 28806–28811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaughan K. T., Vallee R. B. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 1507–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma S., Triviños-Lagos L., Gräf R., Chisholm R. L. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 1261–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King S. J., Brown C. L., Maier K. C., Quintyne N. J., Schroer T. A. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 5089–5097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susalka S. J., Nikulina K., Salata M. W., Vaughan P. S., King S. M., Vaughan K. T., Pfister K. K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32939–32946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tai A. W., Chuang J. Z., Bode C., Wolfrum U., Sung C. H. (1999) Cell 97, 877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purohit A., Tynan S. H., Vallee R., Doxsey S. J. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tynan S. H., Purohit A., Doxsey S. J., Vallee R. B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 32763–32768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang Q., Staub C. M., Gao G., Jin Q., Wang Z., Ding W., Aurigemma R. E., Mulder K. M. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 4484–4496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh T. Y., Peretti D., Chuang J. Z., Rodriguez-Boulan E., Sung C. H. (2006) Traffic 7, 1495–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang X., Plamann M. (2003) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 628–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson C. G., Bloom K. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 481–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiang X., Fischer R. (2004) Fungal Genet Biol. 41, 411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckwith S. M., Roghi C. H., Liu B., Ronald Morris N. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 143, 1239–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B., Xiang X., Lee Y. R. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 47, 291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dick T., Surana U., Chia W. (1996) Mol. Gen. Genet 251, 38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miki F., Okazaki K., Shimanuki M., Yamamoto A., Hiraoka Y., Niwa O. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 930–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis L., Smith G. R. (2005) Genetics 170, 581–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M. G., Serr M., Newman E. A., Hays T. S. (2004) Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 3005–3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuang J. Z., Yeh T. Y., Bollati F., Conde C., Canavosio F., Caceres A., Sung C. H. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sachdev P., Menon S., Kastner D. B., Chuang J. Z., Yeh T. Y., Conde C., Caceres A., Sung C. H., Sakmar T. P. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 2621–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoder J. H., Han M. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2921–2933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivaram M. V., Wadzinski T. L., Redick S. D., Manna T., Doxsey S. J. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 902–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer K. J., Hughes H., Stephens D. J. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 2885–2899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mische S., He Y., Ma L., Li M., Serr M., Hays T. S. (2008) Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 4918–4929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee W. L., Kaiser M. A., Cooper J. A. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 168, 201–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang X., Zuo W., Efimov V. P., Morris N. R. (1999) Curr. Genet 35, 626–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J., Wang L., Zhuang L., Huo L., Musa S., Li S., Xiang X. (2008) Traffic 9, 1073–1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiang X., Roghi C., Morris N. R. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9890–9894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nayak T., Szewczyk E., Oakley C. E., Osmani A., Ukil L., Murray S. L., Hynes M. J., Osmani S. A., Oakley B. R. (2006) Genetics 172, 1557–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu B., Morris N. R. (2000) Mol. Gen. Genet. 263, 375–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuang L., Zhang J., Xiang X. (2007) Genetics 175, 1185–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J., Han G., Xiang X. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 44, 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song J., Tyler R. C., Lee M. S., Tyler E. M., Markley J. L. (2005) J. Mol. Biol. 354, 1043–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lo K. W., Kan H. M., Pfister K. K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9552–9559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han G., Liu B., Zhang J., Zuo W., Morris N. R., Xiang X. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 719–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee W. L., Oberle J. R., Cooper J. A. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 160, 355–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheeman B., Carvalho P., Sagot I., Geiser J., Kho D., Hoyt M. A., Pellman D. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 364–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller R. K., D'Silva S., Moore J. K., Goodson H. V. (2006) Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 76, 49–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenz J. H., Schuchardt I., Straube A., Steinberg G. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2275–2286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abenza J. F., Pantazopoulou A., Rodríguez J. M., Galindo A., Peñalva M. A. (2009) Traffic 10, 57–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zekert N., Fischer R. (2009) Mol. Biol. Cell 20, 673–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.King S. J., Bonilla M., Rodgers M. E., Schroer T. A. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 1239–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caviston J. P., Ross J. L., Antony S. M., Tokito M., Holzbaur E. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 10045–10050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levy J. R., Holzbaur E. L. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 3187–3195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barbar E. (2008) Biochemistry. 47, 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]