Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine the consequences of expression of a novel connexin50 (CX50) mutant identified in a child with congenital total cataracts.

METHODS

The GJA8 gene was directly sequenced. Formation of functional channels was assessed by two-microelectrode voltage-clamp. Connexin protein levels and distribution were assessed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. The proportion of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry.

RESULTS

Direct sequencing of the GJA8 gene identified a 137 G>T transition that resulted in the replacement of glycine by valine at position 46 of the coding region of CX50 (CX50G46V). Both CX50 and CX50G46V induced gap junctional currents in pairs of Xenopus oocytes. In single Xenopus oocytes, CX50G46V induced connexin hemichannel currents that were activated by removal of external calcium; their magnitudes were much higher than those in oocytes injected with similar amounts of CX50 cRNA. When expressed in HeLa cells under the control of an inducible promoter, both CX50 and CX50G46V formed gap junctional plaques. Induction of CX50G46V expression led to a decrease in cell number and an increase in the proportion of apoptotic cells. CX50G46V-induced cell death was prevented by high concentrations of extracellular calcium ions.

CONCLUSIONS

Unlike previously characterized CX50 mutants that exhibit impaired trafficking and/or lack of function, CX50G46V traffics properly to the plasma membrane and forms functional hemichannels and gap junction channels; however, it causes cell death even when expressed at minute levels. The biochemical results indirectly suggest a potential novel mechanism by which connexin mutants could lead to cataracts: cytotoxicity due to enhanced hemichannel function.

INTRODUCTION

Homeostasis in the avascular lens depends on the function of an extensive network of gap junctions.1 Gap junctions are plasma membrane specializations that contain clusters of intercellular channels that allow transfer of molecules up to 1 kDa between communicating cells. Gap junction channels are oligomeric assemblies of subunit proteins called connexins (CX). A gap junction channel is formed by the coaxial alignment of two hexameric hemichannels contributed by apposing cells. Hemichannels at the non-junctional plasma membrane may also be functional and allow communication between the extracellular compartment and the cytoplasm. The repertoire of connexins expressed by lens cells depends on their differentiation stage. Epithelial cells express CX43 and CX50, differentiating cells express CX43, CX46 and CX50, and fiber cells express CX46 and CX50.2–6 Cx46 and Cx50 share some functions in the lens, but Cx46 cannot replace Cx50 in its role in postnatal cell proliferation.7

The importance of gap junctions for lens function has been emphasized by the association of mutations in the human genes encoding CX46 and CX50 (GJA3 and GJA8) with inherited congenital cataracts.8–10 Congenital cataracts account for 10% of childhood blindness and are genetically and phenotypically heterogenous.8 Inheritance is most commonly autosomal dominant although autosomal recessive and X-linked forms have also been reported.

All of the cataract-associated mutant CX46 and CX50 proteins that have been analyzed show impaired trafficking to the plasma membrane and/or lack of formation of functional gap junction channels.11–19 In this paper, we report a novel CX50 mutant that forms functional gap junctional channels and hemichannels, and its expression is associated with decreased cell survival and death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Patient Ascertainment and Collection of Genetic Material

DNA from patients with congenital cataract seen at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the Hospital for Children, Great Ormond Street, London was screened for mutations in the GJA8, gamma S crystallin, EPHA2 receptor tyrosine kinase, and SLC16A12 genes. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local research ethics committee. Written informed consent, which followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, was obtained from all adult individuals and from the parents of children under 16 years of age. Genomic DNA was extracted from venous blood leukocytes using the Nucleon II DNA extraction kit (Tepnel Life Sciences, Wythenshawe, Manchester, UK).

Sequencing

PCRs were carried out with patient genomic DNA as template to amplify the GJA8 gene using the following primers, CX501F: GCTCAGCTCTTGCCTTCTCC, CX501R: GCTGCAGCGGTACAGAGG, CX502F: GGCAGCAAAGGCACTAAGAA, CX502R: CGAACTGATTGAAAGGCTTG, CX503F: CCCACTATTTCCCCTTGACC, CX503R: TCCTTTCATCTTGCCCTACG. PCR products were purified from agarose gels using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Crawley, West Sussex, UK). Direct sequencing of these PCR products identified a heterozygous G>T transition at position 137. The mutation was confirmed by amplifying the coding region of the GJA8 gene, subcloning PCR products into pGEM-TEasy (Promega, Southhampton, UK), and sequencing them. All sequencing reactions were cycle-sequenced with Big Dye Terminator Ready Reaction Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, Cheshire, UK) and were analyzed on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyser (Applied Biosystems).

Subcloning of Human CX50 DNA

Human wild type CX50 coding sequence was subcloned into pSP64TII,18, 20 pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carslbad, CA, USA)18 and pIND(SP1) (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The mutant (CX50G46V) allele was generated by site directed mutagenesis using the Quick Change® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies UK Limited, Chesire, UK) using primers 5’ (GCAGAGTTCGTGTGGGTGGATGAGCAATCCGAC) and 3’ (GTCGGATTGCTCATCCACCCACACGAACTCTGC). Products were sequenced to check the fidelity of the amplification reaction. The PCR products were subcloned into pSP64TII, pcDNA3.1/Hygro(+) and pIND(SP1) vectors.

Expression of Connexins in Xenopus Oocytes

Plasmids were linearized with Sal I. Capped RNA was synthesized using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE® SP6 Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). RNA was quantified by measuring absorbance at 260 nm, and integrity was further assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Adult female Xenopus laevis were anaesthetized with tricaine and a partial ovariectomy was performed. The animals were maintained and treated in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Oocytes were defolliculated and microinjected with an oligonucleotide antisense to the endogenous Xenopus CX38 and 2–4 ng of connexin cRNAs (or no RNA for controls) as previously described.21

Electrophysiological Measurements

Connexin cRNA-injected oocytes were devitellinized.22 Paired and unpaired oocytes were incubated at 18°C for 24 hours before electrophysiological recording. Double two-microelectrode voltage-clamp experiments were performed using Geneclamp 500 and an Axoclamp 2A voltage-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The microelectrodes were filled with 3 M KCl and had a resistance between 0.1 and 0.6 MΩ. To prevent electrode leakage, the tips of the electrodes were backfilled with 1% agar in 3 M KCl. For simple measurements of gap junctional coupling, both cells of a pair were held initially at −40 mV, and voltage clamp steps were applied to one cell whilst holding the second cell at −40 mV. Under these conditions, the change in current measured in the second cell would be equal to the junctional current (Ij), but of opposite polarity. The junctional conductance (gj) was calculated as (gj=Ij/Vj), where Vj = Vcell 2 − Vcell 1. For measurements of hemichannel currents in single oocytes, a series of voltage clamp steps were applied between −70 and +30 mV in increments of 10 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. Pulse generation and data acquisition were performed using a PC computer equipped with PCLAMP6 software and a TL-1 acquisition system (Axon Instruments). Currents were filtered at 20–50 Hz and digitized using PCLAMP6 software and a Digidata 1200 (Axon Instruments). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–22°C).

Cell Culture

HeLa cells were grown in MEM supplemented with non-essential amino acids, 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin G and 100 µg/ml streptomycin sulfate (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Cells were transfected using Lipofectin® Transfection Reagent and Plus™ Reagent according to the manufacturer’s directions (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Stably transfected ponasterone A-inducible cells were grown with 175 µg/ml zeocin (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and 132 µg/ml hygromycin (Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ, USA).

Generation of Ponasterone A-Inducible HeLa Cells

Connexin-deficient HeLa cells were first stably transfected with a plasmid containing DNA coding for the ecdysone receptor (pVgRXR, Invitrogen Life Technologies). Stable expression of the ecdysone receptor was verified by transiently transfecting the cells with a reporter plasmid that drives inducible expression of β-galactosidase (pINDβ-gal, Invitrogen Life Technologies), and performing a β-galactosidase assay after induction with 1 µM ponasterone A (Invitrogen Life Technologies). A positive clone was selected and stably transfected with either wild type human CX50 or CX50G46V subcloned into the pIND(SP1) vector.

Immunoblotting

Cells at about 90% confluence were harvested in PBS, 4 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 1 mg/ml Pefabloc, 10 µg/ml leupeptin, 10 µg/ml pepstatin and 1µg/ml aprotinin and sonicated. The protein concentration in the homogenates was determined by the Bradford assay.23 Aliquots from cell homogenates containing 50 µg of protein were resolved on 9% SDS-containing polyacrylamide gels, transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and subjected to immunoblotting using affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-CX50 antibodies.14

Immunofluorescence

HeLa cells stably transfected with CX50 or CX50G46V subcloned into the pIND(SP1) vector were plated on 4-well LAB-TEK Nalge Nunc International chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA). Twenty four hours later, cells were induced by treatment with 1 µM ponasterone A. Forty eight hours post-induction, cells were rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 15 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. Cells were then permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked in 1% triton X-100, 10% normal goat serum in PBS. Immunofluorescence was performed using affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-CX50 antibodies as previously described.14

Determination of Cell Number

Cells were treated with 1 µM ponasterone A 24 hours after plating. Ninety six hours later, they were observed under the microscope and a minimum of 9 visual fields were photographed. The number of live cells per visual field was manually counted. The results are presented as the number of live cells per mm2 remaining in uninduced and induced cultures (0 ∀ S.E.M.).

MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) assay

The MTS assay (CellTiter 96 AQ nonradioactive cell proliferation assay) was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Cells were plated on 24- well plates. After 24 hours, cells were treated with 1 µM ponasterone A or 0.1% ethanol (the final concentration of ethanol used as solvent for the ponasterone) and incubated for an additional 72 hours. After that time, 200 µl of MTS solution were added to each well, the cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and the absorbance at 490 nm, which is proportional to the number of living/surviving cells, was measured with a DU-64 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA).

Assessment of Apoptosis by Flow Cytometry

HeLa cells were plated on 100 mm dishes and cultured for 24 hours. Then, cells were treated with either 1 µM ponasterone A or ethanol and grown for another 48 hours. The cell culture medium containing floating cells was collected, the attached cells were lifted off from the dish by trypsinization, and the combined cell suspension was centrifuged to pellet the cells. The pellet was rinsed in PBS and centrifuged at 1300 g twice. The pellet was then resuspended in 1.2 ml of PBS. Three ml of ice-cold 95% ethanol were added dropwise while vortexing and the cells were then incubated for 30 minutes. Fifteen ml of PBS were added, and the cells were pelleted at 1900 g for 10 minutes. This was repeated once, and the cells were resuspended in 4.5 ml of PBS. Five hundred µl of 1 mg/ml RNase were added, and the cells were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then rinsed with 5 ml PBS and spun down at 1900 g twice. Finally, the cells were resuspended in 2 ml of propidium iodide (PI) staining solution (10 mg PI/100 ml PBS), and the samples were analyzed on a BD FACScan (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Identification of a Novel CX50 Mutation

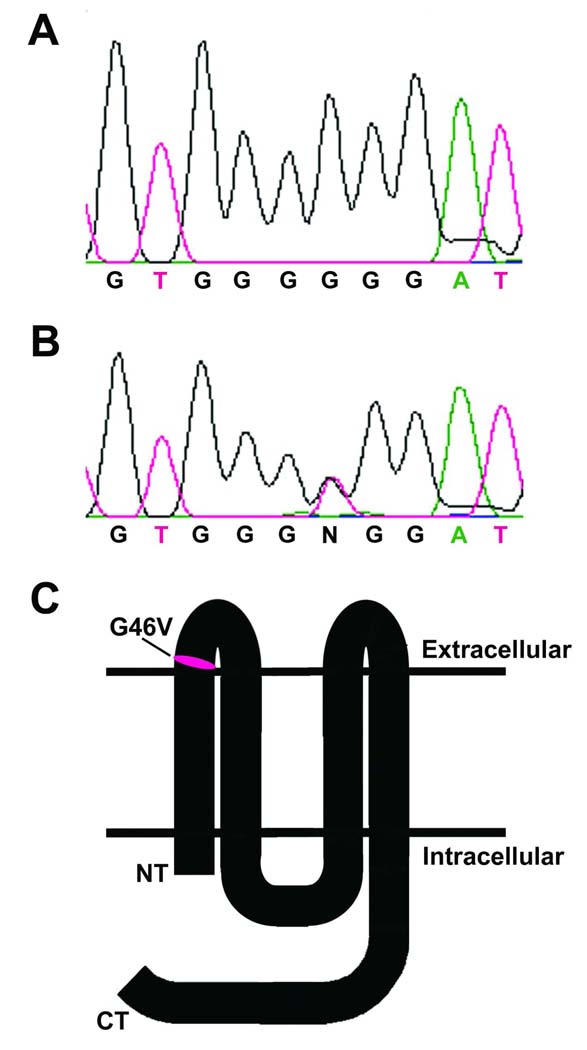

Direct sequencing of the GJA8 gene in a panel of probands with cataract where the underlying causative mutation was not known revealed a novel heterozygous mutation in a child of Palestinian origin with an early onset total cataract. This was confirmed by the cloning of the PCR products and sequencing of the DNA inserts. The GJA8 gene had been screened as part of an ongoing collaboration between the Institute of Ophthalmology and the University of Chicago to determine the role of CX50 in human cataract. The panel has also been screened by ourselves or our collaborators for mutations in the EPHA2 receptor tyrosine kinase gene,24 the gamma S crystallin gene and the SLC16A12 gene. No mutations in these genes were identified in the DNA from this child. The identified mutation corresponded to a 137G>T nucleotide transition within the coding region of CX50 that resulted in the replacement of the glycine at position 46 with a valine (CX50G46V) (Fig. 1A, B). Hydropathicity algorithms predict that this amino acid localizes at the beginning of the first extracellular loop (Fig. 1C). This child also had small eyes and pupils that did not dilate well. Unfortunately, leukocyte samples from the parents and sibling were not available, and they did not consent to further examination or mutation screening. Therefore, segregation of the phenotype and direct genetic correlation of this mutation with the disease are not possible.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of a novel mutation of CX50 in a patient with total cataract. (A, B) Chromatograms show the sequence through the region of the GJA8 gene containing nucleotides 132–141 of the coding region from an unaffected (A) and from the affected (B) individual. (C) Diagram showing the predicted localization of the G46V missense mutation within the topology of CX50 in the plasma membrane.

Effects of CX50G46V Expression

To study the cellular behavior of the mutant CX50 in HeLa cells and compare it with that of wild type CX50, we attempted to isolate stably transfected clones. However, despite multiple attempts using the same strategy previously used to express wild type CX50 and other mutants14, 17, 18, 19, we were unable to obtain any stably transfected clones of HeLa cells expressing CX50G46V. This led us to infer that expression of the CX50G46V protein had deleterious effects.

CX50G46V Forms Functional Channels

The ability of CX50G46V to form functional gap junctional channels was characterized by two-electrode voltage-clamp in Xenopus oocyte pairs. Pairs of oocytes injected with 2–4 ng of CX50G46V cRNA developed gap junctional conductances with mean values that were not significantly different from those determined in oocyte pairs injected with wild type CX50 cRNA (Table 1). Pairs of control oocytes injected with no connexin cRNA showed no coupling.

TABLE 1.

CX50G46V forms functional gap junctional channels.

| Cell 1/Cell 2 | Junctional conductance (µS) | n |

|---|---|---|

| No cRNA/No cRNA | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 8 |

| CX50/CX50 | 41.6 ± 16.8 | 8 |

| CX50G46V/CX50G46V | 51.8 ± 34.2 | 9 |

Gap junctional conductance measured in pairs of Xenopus oocytes injected with no cRNA or cRNA for CX50 or CX50G46V. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

Oocytes expressing CX50G46V showed reduced resting potentials compared to oocytes injected with CX50 cRNA even when the bathing solution contained cobalt ions, which have been previously shown to block other connex in hemichannels.20,25 These results suggest that expression of CX50G46V also had deleterious effects in Xenopus oocytes.

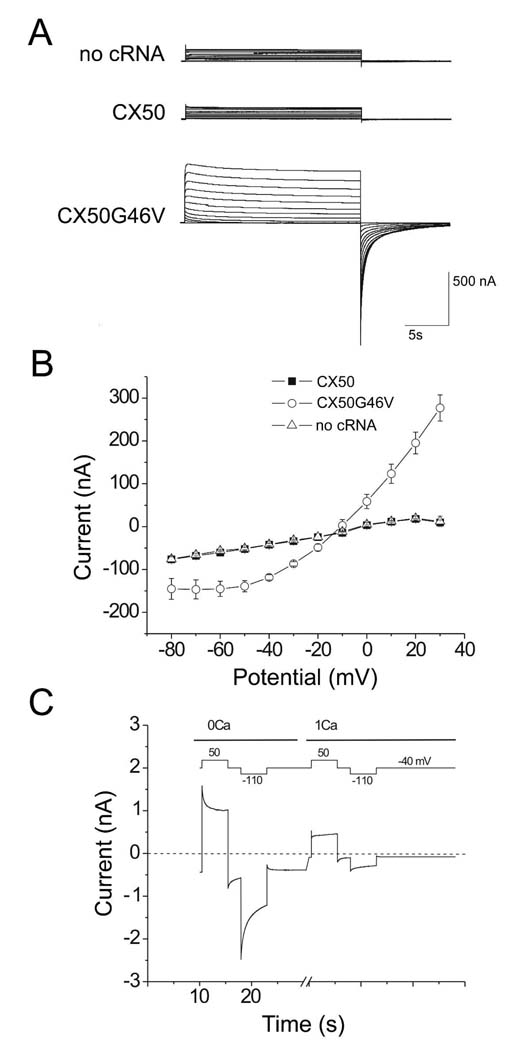

Because the deleterious effects of CX50G46V protein expression could result from connexin-mediated hemichannel activity, we tested the ability of wild type and mutant CX50 to induce macroscopic hemichannel currents in the nonjunctional plasma membrane using a two-electrode voltage-clamp technique in the presence of zero added extracellular Ca2+. Oocytes injected with only 2–4 ng of CX50G46V cRNA developed large outward currents that activated on depolarization (Fig. 2A, B and Table 2). In contrast, little or no detectable hemichannel currents were observed in oocytes injected with wild type CX50 cRNA or antisense-treated control oocytes (Fig. 2A, B and Table 2). The hemichannel currents detected in CX50G46V cRNA-injected oocytes were substantially reduced by increasing the extracellular concentration of Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o) from nominally 0 to 1 mM (Fig. 2C and Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

CX50G46V forms large hemichannel currents in Xenopus oocytes that can be blocked by extracellular calcium ions. (A) Comparison of hemichannel currents in control oocytes (upper panel) or oocytes injected with equal amounts of CX50 (middle panel) or CX50G46V (lower panel) cRNA. Currents were elicited in response to voltage clamp steps between −80 and +30 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −80 mV. (B) Steady-state current-voltage relationships in control, CX50 and CX50G46V cRNA-injected oocytes. Each point in the curve represents the mean ± SEM. Recordings were performed in oocytes kept in modified Barth’s solution containing zero added calcium and 1.0 mM magnesium. (C) Current traces recorded from a CX50G46V cRNA-injected oocyte before and after application of calcium. In the presence of zero added external calcium, a large current was observed that was mostly activated at a holding potential of −40 mV and tended to close on application of large positive and negative voltage clamp steps. Application of 1 mM Ca2+ to the bathing media caused a marked reduction in current amplitude which was more pronounced at negative potentials. The sequence of voltage clamp steps is shown above the currents. The dashed line represents zero current level.

TABLE 2.

CX50G46V forms functional hemichannels.

| Cell | Hemichannel current (nA) | n |

|---|---|---|

| No cRNA | 12.2 ± 12.2 | 2 |

| CX50 | 9.8 ± 5.6 | 3 |

| CX50G46V | 277.1 ± 30.3 | 4 |

Hemichannel currents were measured at +30 mV in single Xenopus oocytes. Data represent mean ± S.E.M.

TABLE 3.

Increased [Ca2+]o inhibits CX50G46V hemichannel currents.

| [Ca2+]o (mM) | Hemichannel current (nA) | n |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 600.6 ± 64.1 | 7 |

| 1 | 115.7 ± 37.3 | 7 |

Hemichannel currents obtained at a holding potential of −40 mV in single Xenopus oocytes. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M.

CX50G46V Expression Decreases Cell Viability/Survival

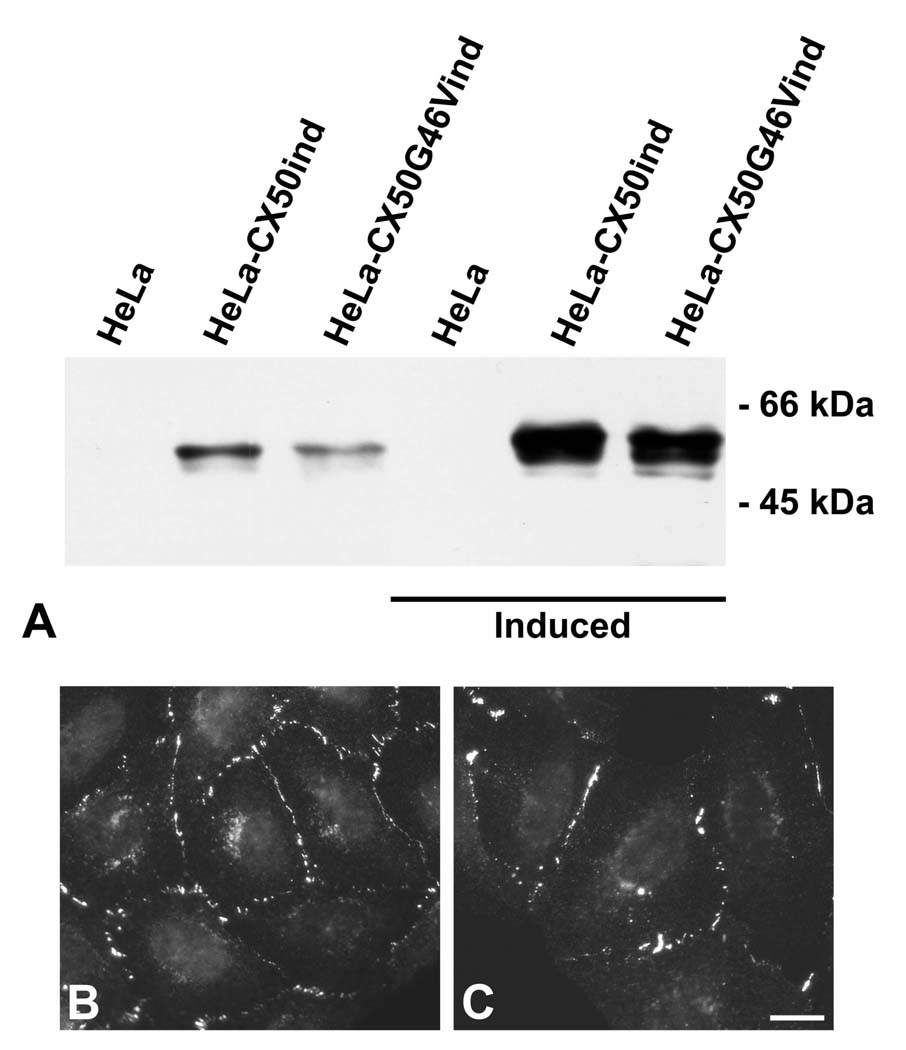

To facilitate study of such potential toxic effect(s) of CX50G46V, we generated HeLa cells stably transfected with wild type CX50 or CX50G46V in which their expression was under the control of a ponasterone A-inducible promoter (HeLa-CX50ind and HeLa-CX50G46Vind, respectively). These clones expressed only a small amount of wild type CX50 or CX50G46V under control conditions (uninduced) as detected by the presence of a band recognized by anti-CX50 antibodies in immunoblots; such a band was not observed in HeLa cells expressing the ecdysone receptor but not transfected with CX50 or CX50G46V (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Immunodetection of wild type and mutant CX50 in HeLa cells. (A) Aliquots from homogenates of untransfected HeLa cells and HeLa cells transfected with wild type CX50 or CX50G46V without induction and after induction with 1 µM ponasterone A for 48 hours were subjected to immunoblotting using anti-CX50 antibodies. No CX50 protein bands were detected in untransfected HeLa cells (HeLa). HeLa cells transfected with wild type or mutant CX50 (HeLa-CX50ind or HeLa-CX50G46Vind, respectively) showed a low level of CX50 protein expression before induction, but the CX50 protein levels increased markedly in both transfected cells after induction. The migration positions of the molecular mass standards are indicated. (B, C) HeLa-CX50ind and HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells were fixed 48 h after induction and subjected to immunofluorescence using anti-CX50 antibodies. Both HeLa-CX50ind (B) and HeLa-CX50G46Vind (C) showed a significant number of gap junctional plaques. Bar, 18 µm.

Induction of HeLa-CX50ind and HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells by ponasterone A treatment led to a marked increase in levels of immunoreactive CX50 bands (Fig. 3A), an effect that was not observed in HeLa cells expressing only the ecdysone receptor (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence microscopy of HeLa-CX50ind and HeLa-CX50G46Vind after ponasterone A treatment revealed that both CX50 and CX50G46V were localized at appositional membranes, where they formed gap junction plaques, and in the perinuclear region, probably the Golgi compartment (Fig. 3B, C). Immunofluorescence microscopy also revealed that not every cell in the HeLa-CX50G46Vind clones showed anti-CX50 immunoreactivity. About 80% of cells were positive. Moreover, the proportion of cells exhibiting CX50 immunoreactivity in the HeLa-CX50G46Vind decreased with successive passages. In contrast, the clones expressing wild type CX50 consistently showed uniform immunostaining.

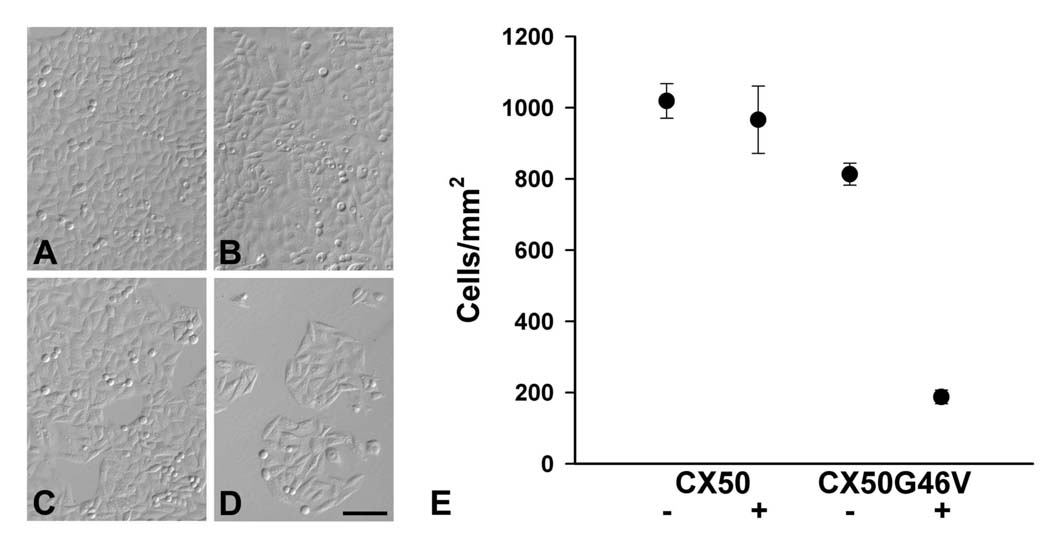

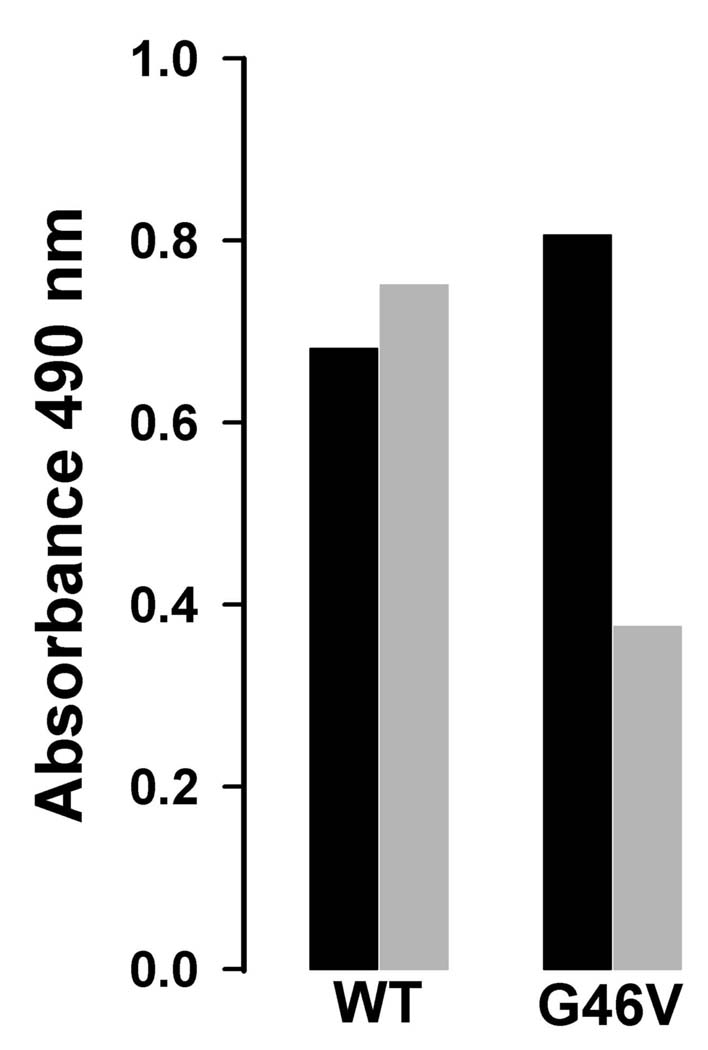

To test directly whether expression of CX50G46V had a deleterious effect on cell growth/survival, we compared the effects of induced CX50 and CX50G46V expression on cell numbers. Cultures of HeLa-CX50ind cells treated with 1 µM ponasterone A for 96 hours contained similar numbers of cells compared to cultures of uninduced cells (Fig. 4A, B). In contrast, a dramatic decrease in cell numbers was observed when comparing ponasterone A-treated with untreated cultures of HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells (Fig. 4C, D). Quantitation of these results revealed no significant difference between uninduced and induced HeLa-CX50ind cells, but the number of cells in induced cultures of HeLa-CX50G46Vind was only about 23% of that observed in uninduced sister cultures (Fig. 4E). Similarly, while induction of CX50 expression for 72 hours had no effect on cell viability as assessed by the colorimetric MTS assay, induction of CX50G46V expression dramatically reduced cell viability (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 4.

Induction of CX50G46V protein expression decreased the number of cells. (A–D) Phase-contrast photomicrographs from cultures of HeLa-CX50ind (A, B) and HeLa- CX50G46Vind (C, D) that were left untreated (A, C) or that were induced with 1 µM ponasterone A (B, D). (E) Graph shows the quantitation of these data as mean ± S.E.M. of the number of cells/mm2 for uninduced (−) and induced (+) cultures of HeLa-CX50ind (CX50) and HeLa-CX50G46Vind (CX50G46V). While the number of cells remaining in the culture was dramatically decreased 96 h after treatment of HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells with ponasterone A, the cell density in HeLa-CX50ind cells was unaffected. Bar, 111 µm.

FIGURE 5.

Expression of CX50G46V protein decreased cell viability/survival. Graph represents the cell viability of HeLa-CX50ind (WT) and HeLa-CX50G46Vind (G46V) that were left untreated (black bars) or that were treated with 1 µM ponasterone A (gray bars) for 72 h. Cell viability was determined using the MTS assay in which the absorbance at 490 nm is proportional to the number of viable cells.

CX50G46V Expression Induces Apoptosis

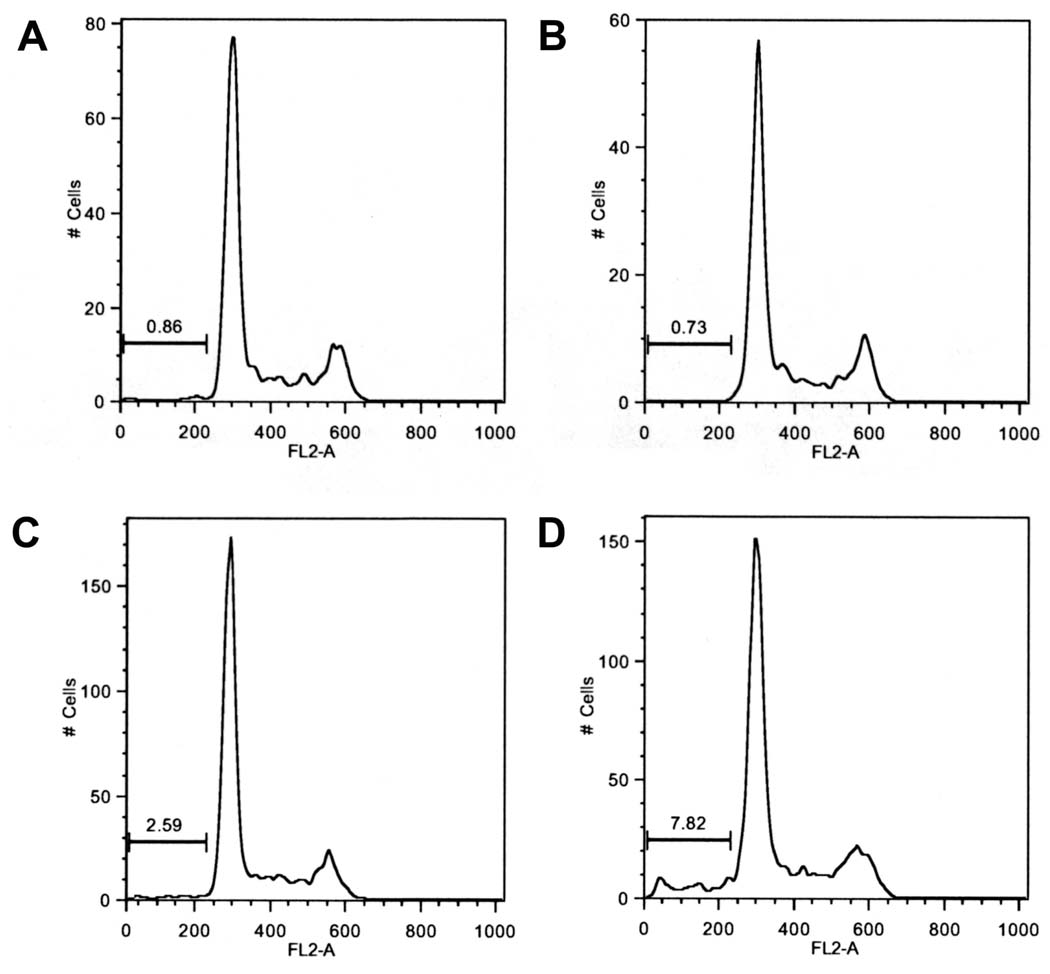

The differential effects of CX50 and CX50G46V on cell numbers prompted us to test whether expression of CX50G46V increased the proportion of cells containing sub-G1 amounts of DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis.26 HeLa-CX50ind and HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells were left untreated or they were treated with 1 µM ponasterone A for 48 hours, labeled with propidium iodide, and cell cycle kinetics were analyzed by flow cytometry. Under control conditions, cells expressing CX50G46V protein showed a higher proportion of cells containing sub-G1 amounts of DNA than cells expressing CX50 (Fig. 6, compare panels A and C). The proportion of apoptotic cells was further increased after ponasterone A-induced expression of CX50G46V (Fig. 6, compare panels C and D), but it remained unaffected after induction of CX50 expression (Fig. 6, compare panels A and B).

FIGURE 6.

Expression of CX50G46V protein increased the proportion of apoptotic cells. Graphs represent the results of cell cycle analysis of propidium iodide-stained HeLa-CX50ind (A, B) and HeLa-CX50G46Vind (C, D) cells that were left uninduced (A, C) or were induced by treatment with 1 µM of ponasterone A for 48 hours (B, D). This analysis revealed an increase in the sub-G1 fraction after induction of CX50G46V protein expression by treatment with 1 µM ponasterone A for 48 h.

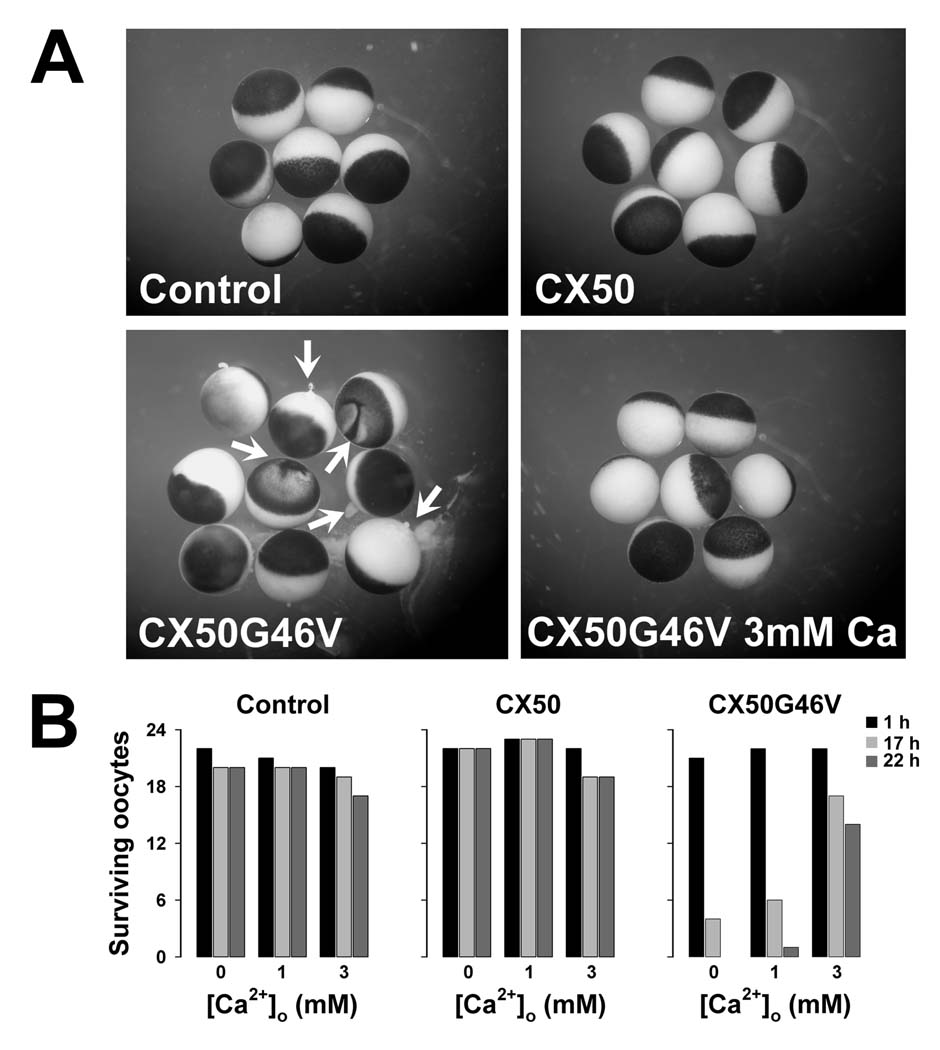

Uncontrolled opening of hemichannels can lead to cell death. To test whether extracellular calcium was sufficient to inhibit this process, we incubated control Xenopus oocytes and oocytes expressing CX50 or CX50G46V in the presence of 0, 1 or 3 mM external calcium. Control oocytes or oocytes injected with CX50 cRNA showed almost 100% survival for at least 22 hours, the latest time assessed (Fig. 7A, B). However, oocytes injected with CX50G46V cRNA incubated in the absence of extracellular calcium showed signs of cell death including irregularities in the boundary between the vegetal and animal poles, discoloration of the pigment in the animal pole and release of cytoplasmic material into the media; these changes were more dramatic at longer times after microinjection of the cRNA (Fig. 7B). Incubation of CX50G46V cRNA-injected oocytes in media containing increasing concentrations of calcium ions resulted in an increasing proportion of normal looking oocytes (Fig. 7B). In the presence of 3 mM extracellular calcium, most of the cells continued to appear normal at 17 and 22 hours after injection of CX50G46V cRNA (Fig. 7A, B).

FIGURE 7.

Expression of CX50G46V induced hemichannel activity-dependent oocyte death. Oocytes were injected with similar amounts of CX50 or CX50G46V cRNA and incubated in modified Barth’s solution containing 0, 1 or 3 mM Ca2+ overnight at 18°C. (A) Oocytes injected with CX50G46V cRNA showed obvious blebbing and discoloration (arrows) when incubated in modified Barth’s solution containing 1 mM Ca2+ for 17 hours (lower left panel). In contrast, oocytes injected with CX50 cRNA or oligonucleotide antisense to the endogenous Xenopus CX38 (Control) showed no apparent detrimental changes when studied under identical conditions (upper panels). The rate of cell death of the CX50G46V cRNA-injected oocytes was significantly reduced by increasing the external calcium concentration from 1 to 3 mM (lower right panel). (B) Graphs represent the number of surviving oocytes at different times following injection of cRNA in media containing 0, 1 or 3 mM Ca2+. Oocytes were scored for cell viability based on appearance as illustrated in A.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have described and characterized a novel CX50 mutant that resulted in the replacement of the glycine at position 46 by a valine. This glycine is highly conserved as it is present in the sequences of all Cx50 orthologs that have been deposited in the database. Moreover, the corresponding residue is a glycine in nine of the other human connexins. The resulting mutant, CX50G46V, traffics properly to the plasma membrane where it forms gap junction plaques and functional channels. Yet, the viability of cells expressing this mutant is reduced.

The CX50 mutant described in this study, CX50G46V, is unique compared with the previously characterized cataract-associated connexin mutants, because it can form functional gap junctional plaques as efficiently as wild type CX50. Previously described human and mouse mutants within the same region (e.g., CX50E48K, CX50D47N, mCX50D47A, mCX50S50P) are nonfunctional when expressed by themselves.12,16,19,27 These results imply that not all mutations in amino acids within the first extracellular loop of CX50 result in loss of intercellular coupling. They also imply that replacement of glycine at position 46 by valine does not alter the docking capability of CX50 hemichannels to form gap junctional channels.

One of the most interesting features of CX50G46V is its significantly increased ability to form functional hemichannels as compared to wild type CX50; injection of minute amounts of CX50G46V cRNA was sufficient to induce large hemichannel currents. Wild type CX50 is much less efficient at forming functional hemichannels than wild type CX46 and its orthologs28,29 which have been extensively studied to characterize hemichannel properties.20,25,30–32 The hemichannel currents in oocytes injected with CX50G46V cRNA exhibited properties similar to those of CX46 hemichannels; they activated upon depolarization and showed a reversal potential at around −10 mV.20,25,30 Similar to mouse CX50 and rat CX46 hemichannel currents25,28,32,33, the magnitudes of CX50G46V hemichannel currents were dependent on the extracellular concentration of Ca2+.

Formation of functional hemichannels by CX50G46V suggests that amino acid residue 46, which has been suggested to line the pore in the open state34, is important for CX50 hemichannel behavior. The presence of a glycine at position 46 may minimize the opening of CX50 hemichannels at physiological concentrations of extracellular Ca2+. Interestingly, a disease-associated form of CX26 with a missense mutation at the corresponding position (CX26G45E) also has an increased capability to form hemichannels as compared to wild type CX26.35, 36 This suggests that the hemichannel behavior of other wild type and mutant connexins may also be modulated by the identity of the amino acid residue present at this position.

Several lines of evidence indicated that expression of CX50G46V in mammalian cells had deleterious effects: (1) we were unable to obtain HeLa cell clones that constitutively expressed CX50G46V; (2) cell number and viability were markedly reduced in cultures that had been induced to express CX50G46V; (3) expression of CX50G46V led to an increase in the proportion of cells containing sub-G1 amounts of DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis26; and (4) CX50G46V expression was lost with subculturing of cells. None of these effects was observed in cells expressing wild type CX50.

The deleterious effects on cell survival are likely responsible for the loss of expression of the mutant protein in HeLa-CX50G46Vind cells with successive subculturing, especially if we consider that the expression system used was rather “leaky” (as indicated by the presence of a CX50 band in immunoblots from samples of uninduced cells), there was some heterogeneity in the HeLa-CX50G46Vind cell clones (i.e., not all cells showed expression of CX50G46V after induction), and the low levels of CX50G46V expression in uninduced cultures were sufficient to increase the proportion of apoptotic cells as compared to uninduced HeLa-CX50ind cells. All of these factors would favor the expansion of the cells that did not express the mutant protein.

Our data showed that induction of CX50G46V expression for 72 hours led to about 50% reduction in cell viability as assessed by the MTS assay, and CX50G46V expression for 96 hours led to a 77% decrease in the number of cells as compared to uninduced cultures. These decreases result at least in part from induction of apoptosis in cells expressing CX50G46V. Because no activators of this pathway were added to the cultures, our data imply that expression of CX50G46V protein per se led to activation of apoptosis. One possible explanation for this lies in the capacity of CX50G46V to form functional hemichannels. Opening of CX50 hemichannels would allow ions to flow according to their concentration gradients. The resulting imbalance in intracellular ion homeostasis may lead to induction of apoptosis. Similar to CX50G46V, the disease-associated mutant CX26G45E is also able to induce apoptosis when transfected into HEK293 cells.35 In our experiments, the dependence of CX50G46V-induced cell death on hemichannel activity was suggested by the survival of cells at increased extracellular concentrations of Ca2+.

The differences between the percentage of apoptotic cells 48 hours after induction (about 10%) and the percentage of viable cells observed in the next 24–48 hours after induction (less than 50%) suggests that expression of the mutant CX50 has other deleterious cellular effects in addition to induction of apoptosis. CX50G46V may have caused non-apoptotic cell death or inhibited proliferation of the HeLa cells. In fact, gap junctional coupling provided through wild type CX50 has been implicated in postnatal lens cell proliferation in mice.37

In the lens, CX50G46V hemichannels may be functional, because the aqueous humor bathing it contains a lower concentration of calcium ions than serum or culture medium.38 How then might the expression of a mutant connexin with increased hemichannel activity affect the viability of lens cells? At the cellular level, opening of CX50G46V hemichannels may trigger a complex sequence of events including loss of membrane potential, disruption of transmembrane ion gradients, and entry of calcium ions, followed by decreased metabolic activity (and loss of cytoplasmic ATP) and finally decreased cell growth and cell death. Extrapolating to the lens, the expression of CX50G46V could have similar effects to those observed following expression of toxic proteins, leading to abnormal lens development and microphthalmia.39, 40 Based on the functional and biochemical data and the patient’s presentation with bilateral congenital cataracts, it is possible that there is a causative link, although we do not have direct genetic evidence as we were unable to obtain samples from other family members. Confirmation of the role of this mutation in cataract formation will depend on the identification of this mutation in other family members or individuals with inherited cataract.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Xiaoqin Xiu for performing the initial electrophysiological studies of this mutant.

Supported by National Institute of Health Grants RO1 EY08368 (ECB) and RO1 EY10589 (LE) and the Wellcome Trust Grant 068083 (AA)

References

- 1.Goodenough DA. The crystalline lens. A system networked by gap junctional intercellular communication. Semin Cell Biol. 1992;3:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4682(10)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer EC, Kistler J, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. Antisera directed against connexin43 peptides react with a 43-kD protein localized to gap junctions in myocardium and other tissues. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:595–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Musil LS, Beyer EC, Goodenough DA. Expression of the gap junction protein connexin43 in embryonic chick lens: molecular cloning, ultrastructural localization, and post-translational phosphorylation. J Membr Biol. 1990;116:163–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01868674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul DL, Ebihara L, Takemoto LJ, Swenson KI, Goodenough DA. Connexin46, a novel lens gap junction protein, induces voltage-gated currents in nonjunctional plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1077–1089. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.4.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White TW, Bruzzone R, Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Mouse Cx50, a functional member of the connexin family of gap junction proteins, is the lens fiber protein MP70. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:711–720. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.7.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rong P, Wang X, Niesman I, et al. Disruption of Gja8 (α8 connexin) in mice leads to microphthalmia associated with retardation of lens growth and lens fiber maturation. Development. 2002;129:167–174. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White TW. Unique and redundant connexin contributions to lens development. Science. 2002;295:319–320. doi: 10.1126/science.1067582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy MA, Francis PJ, Berry V, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. Molecular genetic basis of inherited cataract and associated phenotypes. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49:300–315. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hejtmancik JF. Congenital cataracts and their molecular genetics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:134–149. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berthoud VM, Beyer EC. Oxidative stress, lens gap junctions, and cataracts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:339–353. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal JD, Berthoud VM, Beyer EC, Mackay D, Shiels A, Ebihara L. Molecular mechanism underlying a Cx50-linked congenital cataract. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C1443–C1446. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.6.C1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu X, Ebihara L. Characterization of a mouse Cx50 mutation associated with the No2 mouse cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1844–1850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pal JD, Liu X, Mackay D, et al. Connexin46 mutations linked to congenital cataract show loss of gap junction channel function. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C596–C602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.3.C596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berthoud VM, Minogue PJ, Guo J, et al. Loss of function and impaired degradation of a cataract-associated mutant connexin 50. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82:209–221. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minogue PJ, Liu X, Ebihara L, Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. An aberrant sequence in a connexin46 mutant underlies congenital cataracts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40788–40795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504765200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeRosa AM, Xia CH, Gong X, White TW. The cataract-inducing S50P mutation in Cx50 dominantly alters the channel gating of wild-type lens connexins. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:4107–4116. doi: 10.1242/jcs.012237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas BC, Minogue PJ, Valiunas V, et al. Cataracts are caused by alterations of a critical N-terminal positive charge in connexin50. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2549–2556. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora A, Minogue PJ, Liu X, et al. A novel GJA8 mutation is associated with autosomal dominant lamellar pulverulent cataract: further evidence for gap junction dysfunction in human cataract. JMed Genet. 2006;43:e2. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arora A, Minogue PJ, Liu X, et al. A novel connexin50 mutation associated with congenital nuclear pulverulent cataracts. J Med Genet. 2008;45:155–160. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.051029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ebihara L, Berthoud VM, Beyer EC. Distinct behavior of connexin56 and connexin46 gap junctional channels can be predicted from the behavior of their hemi-gap-junctional channels. Biophys J. 1995;68:1796–1803. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80356-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong JJ, Liu X, Dong L, Ebihara L. Exchange of gating properties between rat cx46 and chicken cx45.6. Biophys J. 2004;87:2397–2406. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.039594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebihara L. Expression of gap junctional proteins in Xenopus oocyte pairs. Methods Enzymol. 1992;207:376–380. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(92)07026-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang T, Hua R, Xiao W, et al. Mutations of the EPHA2 receptor tyrosine kinase gene cause autosomal dominant congenital cataract. Hum Mut. 2009;30:E603–E611. doi: 10.1002/humu.20995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebihara L, Steiner E. Properties of a nonjunctional current expressed from a rat connexin46 cDNA in Xenopus oocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:59–74. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ormerod MG, Collins MKL, Rodriguez-Tarduchy G, Robertson D. Apoptosis in interleukin-3-dependent haemopoietic cells. Quantification by two flow cytometric methods. J Immunol Methods. 1992;153:57–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90305-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beyer EC, Rodriguez J, Minogue PJ, Pal J, Berthoud VM, Ebihara L. Molecular mechanism underlying a congenital "zonular nuclear" pulverulent cataract associated with a connexin50 mutation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48 E-Abstract 3635. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebihara L, Xu X, Oberti C, Beyer EC, Berthoud VM. Co-expression of lens fiber connexins modifies hemi-gap-junctional channel behavior. Biophys J. 1999;76:198–206. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77189-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beahm DL, Hall JE. Hemichannel and junctional properties of connexin 50. Biophys J. 2002;82:2016–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75550-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta VK, Berthoud VM, Atal N, Jarillo JA, Barrio LC, Beyer EC. Bovine connexin44, a lens gap junction protein: molecular cloning, immunologic characterization, and functional expression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3747–3758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trexler EB, Bukauskas FF, Bennett MVL, Bargiello TA, Verselis VK. Rapid and direct effects of pH on connexins revealed by the connexin46 hemichannel preparation. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:721–742. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srinivas M, Calderon DP, Kronengold J, Verselis VK. Regulation of connexin hemichannels by monovalent cations. J Gen Physiol. 2005;127:67–75. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valiunas V, Weingart R. Electrical properties of gap junction hemichannels identified in transfected HeLa cells. Pflügers Arch. 2000;440:366–379. doi: 10.1007/s004240000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verselis VK, Trelles MP, Rubinos C, Bargiello TA, Srinivas M. Loop gating of connexin hemichannels involves movement of pore-lining residues in the first extracellular loop domain. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4484–4493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807430200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stong BC, Chang Q, Ahmad S, Lin X. A novel mechanism for connexin 26 mutation linked deafness: cell death caused by leaky gap junction hemichannels. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:2205–2210. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000241944.77192.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerido DA, DeRosa AM, Richard G, White TW. Aberrant hemichannel properties of Cx26 mutations causing skin disease and deafness. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C337–C345. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00626.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White TW, Gao Y, Li L, Sellitto C, Srinivas M. Optimal lens epithelial cell proliferation is dependent on the connexin isoform providing gap junctional coupling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5630–5637. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duncan G, Jacob TJC. Calcium and the physiology of cataract. Ciba Found Symp. 1984;106:132–152. doi: 10.1002/9780470720875.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breitman ML, Clapoff S, Rossant J, et al. Genetic ablation: targeted expression of a toxin gene causes microphthalmia in transgenic mice. Science. 1987;238:1563–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.3685993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Landel CP, Zhao J, Bok D, Evans GA. Lens-specific expression of recombinant ricin induces developmental defects in the eyes of transgenic mice. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1168–1178. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.9.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]