Abstract

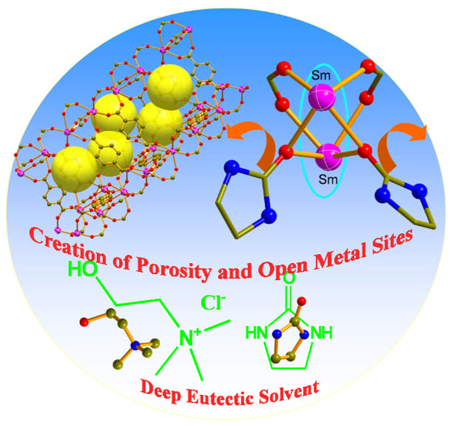

Trap it in and burn it out: the deep eutectic solvent provides a versatile route for the creation of highly stable porous frameworks encapsulating neutral coordinating ligand molecule, which can escape intact from the pore upon heating to directly become crystals, leaving behind permanent porosity and coordinatively unsaturated metal sites with potential applications in gas storage and catalysis.

Keywords: Deep eutectic solvent, metal-organic framework, template, ionic liquid, crystal structure

Because of the unique integration of various properties such as excellent solvating properties, wide reaction temperature range, non-volatility, and high thermal stability, ionic liquids have attracted increasing attention as the solvent of choice for chemical synthesis.[1] In the past several years, the synthetic success using the ionothermal method has opened up a new route for the creation of novel inorganic and metal-organic framework materials.[2–7] Recently, Morris et al. reviewed this burgeoning area.[2b,2h]

One type of ionic liquids (denoted as IL here) such as 1-ethyl-3-methyl imidazolium bromide are ionic compounds.[6] In addition to their solvent property, cationic and anionic parts of such ionic liquids can influence the synthetic process through direct incorporation (either individually or in combination) into crystal structures.[7]

There is also another type of ionic liquids—deep eutectic solvents (denoted as DES here). Unlike IL, DES is a mixture with the freezing point lower than either of its two individual compounds. DES contains an ionic compound and a molecular compound. Examples of DES include mixtures of quaternary ammonium salts (e.g., choline chloride) with neutral organic hydrogen bond donors (such as amides, amines, and carboxylic acids).[5, 8] As an ionic liquid, DES shares many characteristics of IL. In addition, one advantage of DES such as choline chloride/(urea or its derivatives) is their low cost. This makes DES particularly desirable for applications in the large-scale synthesis of new functional materials.

Being a mixture, DES (a tri-component system with cations, anions, and neutral ligands) is more complicated than IL (a bi-component system with anions and cations). In addition to cations and anions, DES also contains neutral ligand molecules such as urea that can exert structure-directing effects. In this sense, DES possesses features of both IL and molecular solvents. Each of the three individual components (cations, anions, and neutral ligands) has the potential to participate in the self-assembly process, either individually or in combination with another component, making it possible to create new types of chemistry that are not accessible in either IL or molecular solvents.

We are especially interested in DES because it provides a unique route for the creation of porosity and coordinatively unsaturated metal centers which have been shown to be desirable for enhancing gas storage capacity and for promoting catalytic activity.[3, 9] This is because the neutral ligand, such as urea or its derivatives which is an inherent part of the solvent, has a strong tendency to bind to metal sites. Upon removal of such neutral ligands, both porosity and open metal sites can be created. Furthermore, as shown in this work, the DES is recyclable, because the neutral ligand which serves as the template to generate porosity and open metal sites, can be completely recovered through crystallization immediately following its removal from the pore. This recyclability represents an additional advantage of the method reported here.

Prior to this work, DES has been shown to be an effective solvent and structure-directing agents (SDA) in the synthesis of a number of materials, generally with inorganic framework such as various metal phosphates and phosphonates.[2e, 2f] Of particular interest is the recent demonstration by Morris et al. that unstable DES can serve as template-delivery agents through decomposition.[2f] For example, ethyleneurea can decompose to deliver ethylenediamine which in the protonated form, can direct the formation of zeolite-type metal phosphates. In comparison, there has been relatively limited research on the use of DES for the synthesis of metal-organic framework materials.[5] Because the reaction temperature used for the synthesis of metal-organic framework materials is usually lower than that used for the synthesis of inorganic frameworks (e.g., phosphates), we anticipate that DES would be less likely to decompose and could therefore exert structure-directing effects that differ from that observed in the synthesis of metal phosphates.[2f]

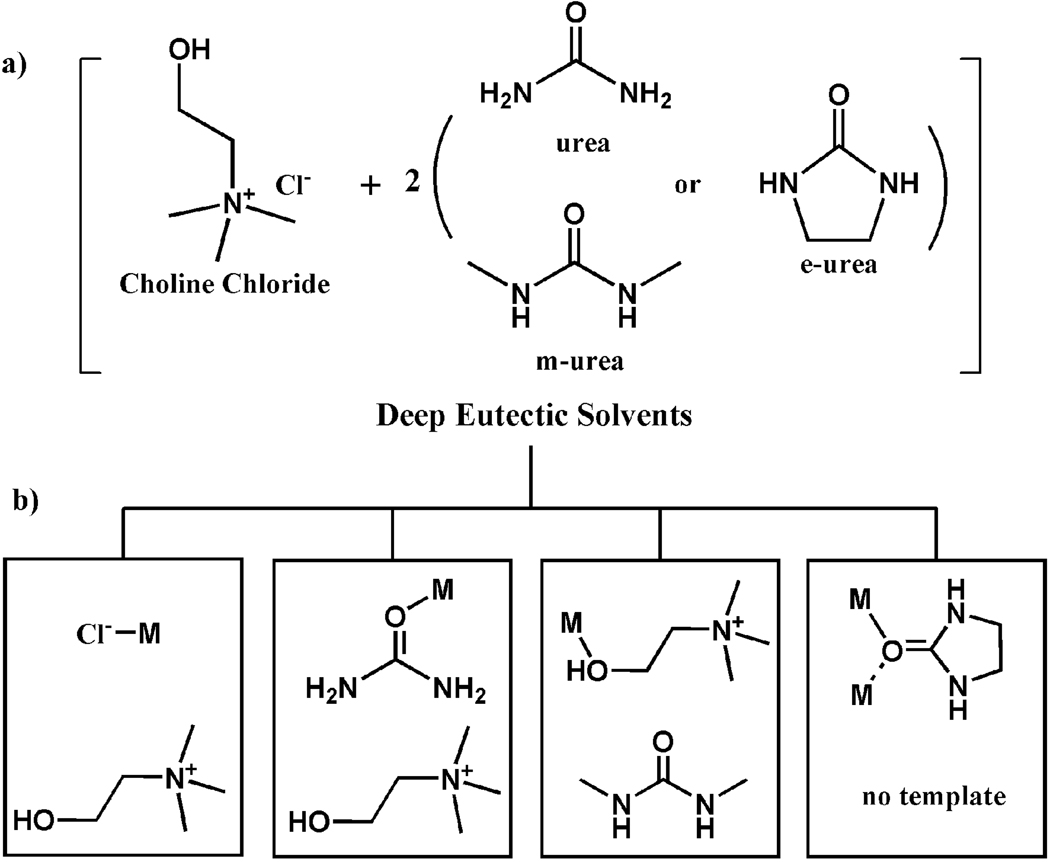

Here, we report a series of metal-organic frameworks synthesized by using three deep eutectic solvents (Scheme 1a). The self-assembly of the trivalent metals (In3+, Y3+, Nd3+, Sm3+, Gd3+, Dy3+, Ho3+ and Yb3+), 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate (bdc), and one or two components of DES generates ten different materials in six distinct framework topologies (Table 1).

Scheme 1.

The deep eutectic solvents (a) and their multiple roles (b, M = metal).

Table 1.

Summary of Crystal Data and Refinement Results.[a]

| Compound | Formula | Space Group | a[Å] | b[Å] | c[Å] | α[°] | β[°] | γ[°] | R(F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (Choline)[InCl(bdc)3/2(H2O)2]·H2O | P21/c | 10.6925(2) | 17.6168(4) | 12.1630(3) | 90.00 | 114.025(2) | 90.00 | 0.0538 |

| 2 | (Choline)[Yb(bdc)2(urea)] | P-1 | 8.4034(1) | 10.5334(1) | 14.3515(1) | 100.83(1) | 103.41(1) | 101.56(1) | 0.0191 |

| 2a | (Choline)[Sm(bdc)2(urea)] | P-1 | 8.3898(1) | 10.6559(2) | 14.3877(2) | 101.964(1) | 102.864(1) | 102.681(1) | 0.0206 |

| 2b | (Choline)[Y(bdc)2(urea)] | P-1 | 8.3734(2) | 10.5740(2) | 14.3077(3) | 101.478(1) | 103.120(1) | 102.247(1) | 0.0390 |

| 3 | [Nd(bdc)2(Choline)]·(m-urea) | P21/n | 14.4400(3) | 12.2290(2) | 14.5152(3) | 90.00 | 104.657(1) | 90.00 | 0.0482 |

| 4 | Gd2(bdc)3(m-urea)4 | P21/n | 8.8307(3) | 13.7279(4) | 18.6260(5) | 90.00 | 94.452(2) | 90.00 | 0.0312 |

| 5 | Yb2(bdc)3(e-urea)4 | P-1 | 9.7863(7) | 10.2967(7) | 11.0263(7) | 76.898(5) | 76.240(5) | 65.487(5) | 0.0301 |

| 5a | Dy2(bdc)3(e-urea)4 | P-1 | 9.8283(1) | 10.4362(1) | 11.0760(1) | 76.894(1) | 76.296(1) | 65.999(1) | 0.0158 |

| 5b | Ho2(bdc)3(e-urea)4 | P-1 | 9.8113(2) | 10.4188(2) | 11.0768(2) | 76.721(1) | 76.242(1) | 65.932(1) | 0.0176 |

| 6 | Sm(bdc)3/2(e-urea) | C2/c | 20.8389(2) | 10.6902(1) | 16.3858(2) | 90.00 | 111.973(1) | 90.00 | 0.0223 |

bdc = 1,4-benzenedicarboxylate; choline = [(CH3)3NCH2CH2OH]+; m-urea = N,N’-dimethylurea; e-urea = ethyleneurea

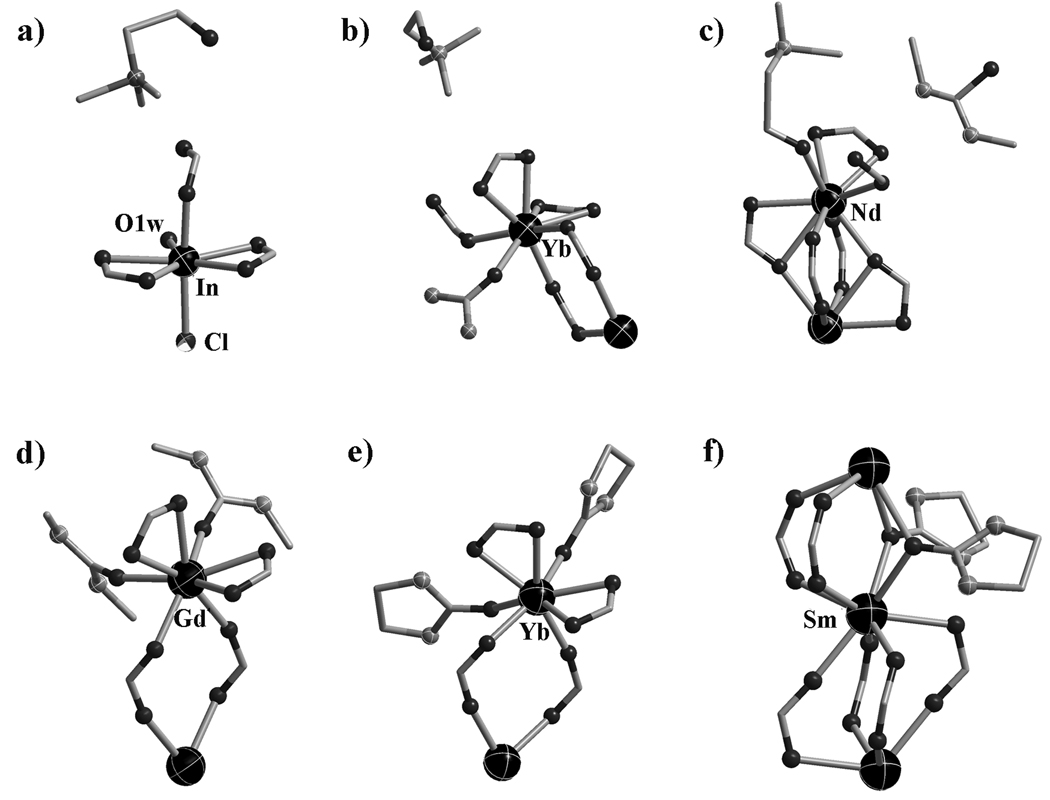

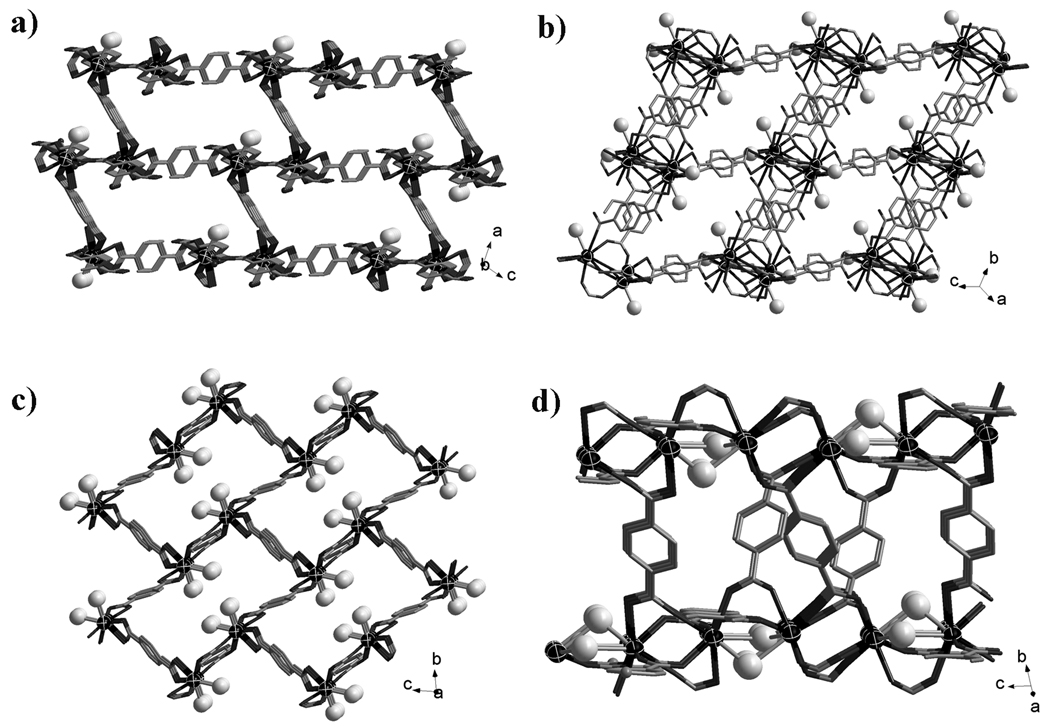

Of particular interest is the demonstration of versatile structure-directing roles of DES (Scheme 1b and Figure 1), in addition to its role as a solvent. The first role, observed in compound 1, is the incorporation of both cations and anions. In compound 1, cationic choline ions act as extra-framework SDAs while the Cl− anions are bonded onto the polymeric layers (Scheme 1b, Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

The coordination environment of the metal sites as well as the guest component in each compound (a, 1; b, 2; c, 3; d, 4; e, 5; f, 6.). Black ball: O; Grey ball: N.

In the second and third roles, cations and neutral ligands are incorporated into the structures. The incorporation of cations and neutral ligands results from the combined effect of the ionic compound and the neutral molecule in DES. The second role is observed in three isostructural compounds 2, 2a and 2b, in which choline ions perform the same role as in compound 1 (i.e., as extra-framework SDAs). However, neutral urea molecules (instead of Cl− in compound 1) are bonded to the framework (Scheme 1b, Figure 1b).

The third role, observed in compound 3, is in fact the reverse of the second role, because it is choline ions that are bonded to the framework through its -OH group while the neutral m-urea molecules serve as extra-framework SDAs (Scheme 1b, Figure 1c). Finally, the fourth role, observed in compounds 4 to 6, is the direct bonding of neutral m-urea or e-urea to the polymeric framework (Scheme 1b, Figure 1d–f). Of these materials, 5, 5a and 5b are most related to the 4-connected silica-type structures, because they possess the moganite-type topology.

It is worth noting that 9 out of 10 materials reported here contain the neutral component in DES (urea, m-urea or e-urea). This demonstrates the strong tendency for the incorporation of neutral ligands when the synthesis is performed in the DES. This forms the basis for the creation of porosity and open metal sites in this work.

Compound 1 exhibits 2D anionic (6,3) layer [InCl(bdc)3/2(H2O)2]nn−, and the guest choline ions are located in the 1D channel (along the c axis) formed from adjacent layers via the hydrogen bonding interactions (Figure S1 in Supporting information).

Compounds 2, 2a and 2b are isostructural, and all of them exhibit similar 3D anionic framework charge-balanced by guest choline cations. In 2, three independent bdc ligands adopt two coordination modes (Scheme 2a, 2c). The urea ligand uses the O donor to coordinate with the Yb3+ site and its two amino groups form NH…O hydrogen bonds with the adjacent bdc ligands (Figure 1b). Each 8-coordinate Yb3+ site is connected by two µ2-bdc ligands and three µ3-bdc ligands, resulting in the formation of a 3D framework with large 1D channels along the b axis (Figure 2a). The quadrangular channel with dimension of 10.89 × 14.85 Å is filled with guest choline cations. By reducing the µ3-bdc ligands as the 3-connected nodes and the Yb3+ sites as the 5-connected nodes, the anionic framework of 2 can be represented as a (3,5)-connected net with the Schläfli symbol of (42.65.83)(42.6).[10]

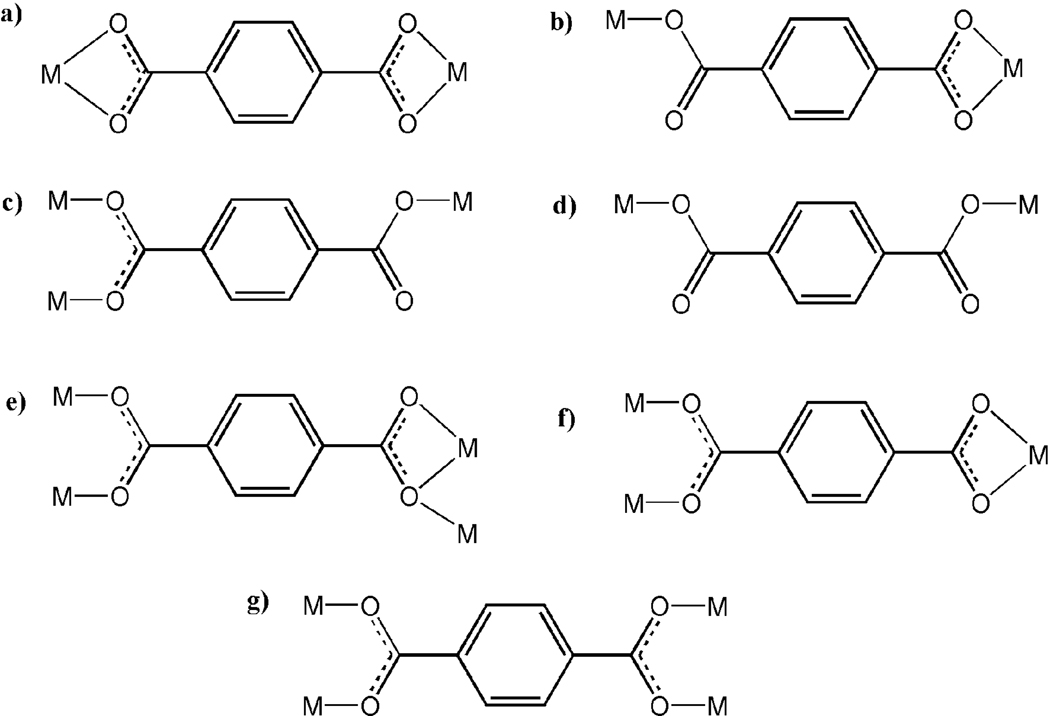

Scheme 2.

The observed coordination modes of the bdc ligands.

Figure 2.

View of the 3D frameworks of the compounds (a, 2; b, 3; c, 5; d, 6). The components of DES attached to each framework are omitted for clarity and the potential binding sites of metals in each framework are shown as grey spheres.

Compared to the anionic frameworks of compounds 1, 2, 2a, and 2b prepared from the choline chloride/urea DES, compounds 3 to 6 have neutral frameworks when the larger urea derivatives (m-urea and e-urea) were used to form the DES.

The most unusual feature of compound 3 is that the positively charged choline ion serves as a ligand bonded to a metal cation, while neutral m-urea acts as an extra-framework template. Such a reversal of roles (c.f. compound 2) between neutral urea-type ligand and choline cation is quite unusual. Compound 3 features an 8-connected CsCl-type network based on dinuclear Nd3+ units. The bdc ligands adopt three different coordination fashions (Scheme 2a, 2d and 2e) to link the dinuclear Nd3+ unit. Each Nd3+ ion is 9-coordinate by eight O atoms from six bdc ligands and one O atom from the choline ion (Figure 1c). Each dinuclear Nd3+ unit is connected to eight adjacent dinuclear Nd3+ units by eight bdc ligands, resulting in an 8-connected framework with 1D channels filled with the guest m-urea molecules and dangling choline ions (Figure 2b).

Compound 4 is also synthesized by using the choline chloride/m-urea DES. However, different from 3, only m-urea from the DES is included in the crystal. In 4, each dinuclear Gd3+ unit is bounded by four m-urea ligands and six bdc ligands with two types of coordination fashions (Figure 1d, Scheme 2a and 2f). The connectivity between the dinuclear Gd3+ units and the bdc ligands generates a neutral 6-connected (3,6)-sheet (Figure S6 in Supporting information).

The use of e-urea leads to a distinct 3D neutral framework 5, also with the neutral ligand only, as in 4. Three independent bdc ligands in 5 adopt two coordination fashions (Scheme 2a and 2f), and all are located at the inversion center. Each Yb3+ site in 5 acts as a 4-connected node (Figure 1e) and is connected by four bdc ligands into a 3D framework with large 1D channels along the a axis (Figure 2c). By considering the µ4-bdc ligands as the planar 4-connected nodes, the framework of 5 can be represented as the 4-connected moganite (denoted: mog) net. Thus, the use of DES provides an alternative path for constructing the low-connectivity frameworks from high coordination element.

The replacement of Yb(NO3)3·xH2O by Dy(NO3)3·xH2O or Ho(NO3)3·xH2O allow the preparation of isostructural compounds 5a or 5b, respectively. On the other hand, the use of Sm(NO3)3·xH2O under similar conditions gives a distinct structure 6. Such an observation of two different structures (compound 5 from Yb3+ and compound 6 from Sm3+) in the DES with e-urea is in distinct contrast with isostructural compounds 2 (Yb3+) and 2a (Sm3+), which demonstrates that the nature of the DES plays an important role in the self-assembly process.

The e-urea ligand in 6 adopts µ2-bridging mode and two e-urea ligands doubly link two symmetry-related 8-coordinate Sm3+ sites with the Sm…Sm distance being 3.959 Å. Each Sm3+ site is bonded to six O atoms from six bdc ligands and two O atoms from two e-urea ligands (Figure 1f). The Sm—O distances (2.533 and 2.607 Å) between Sm and e-urea ligand are longer than that between Sm and the bdc ligand (average 2.391 Å). The carboxylate groups of the bdc ligands exhibit the same µ2-bridging fashion (Scheme 2f) and bridge Sm3+ sites into a chain along the c axis. Two O donors of two e-urea ligand complete two sites of the half paddle wheel dinuclear unit. Each carboxylate-bridged Sm chain is further linked to six neighbouring chains by the bdc ligands, to generate a 3-D neutral framework (Figure 2d). The framework topology can be represented as a (4,6)-connected net by reducing the bdc ligand as the planar 4-connected node and each Sm3+ site as a 6-connected node. The Schläfli symbol of this 3-nodal (4,6)-connected net is (42.63.8)(43.63)2(48.66.8)2.[10]

Compound 6 has a very high thermal stability and was selected to demonstrate the porosity and gas storage properties of materials accessible through synthesis in DES. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of 6 indicates that the first weight loss of 17.7% between 250–300 °C corresponds to the full liberation of e-urea molecules (without decomposition) (calcd: 17.8%) and the remaining framework [Sm(bdc)3/2]n shows no weight loss until 525 °C.

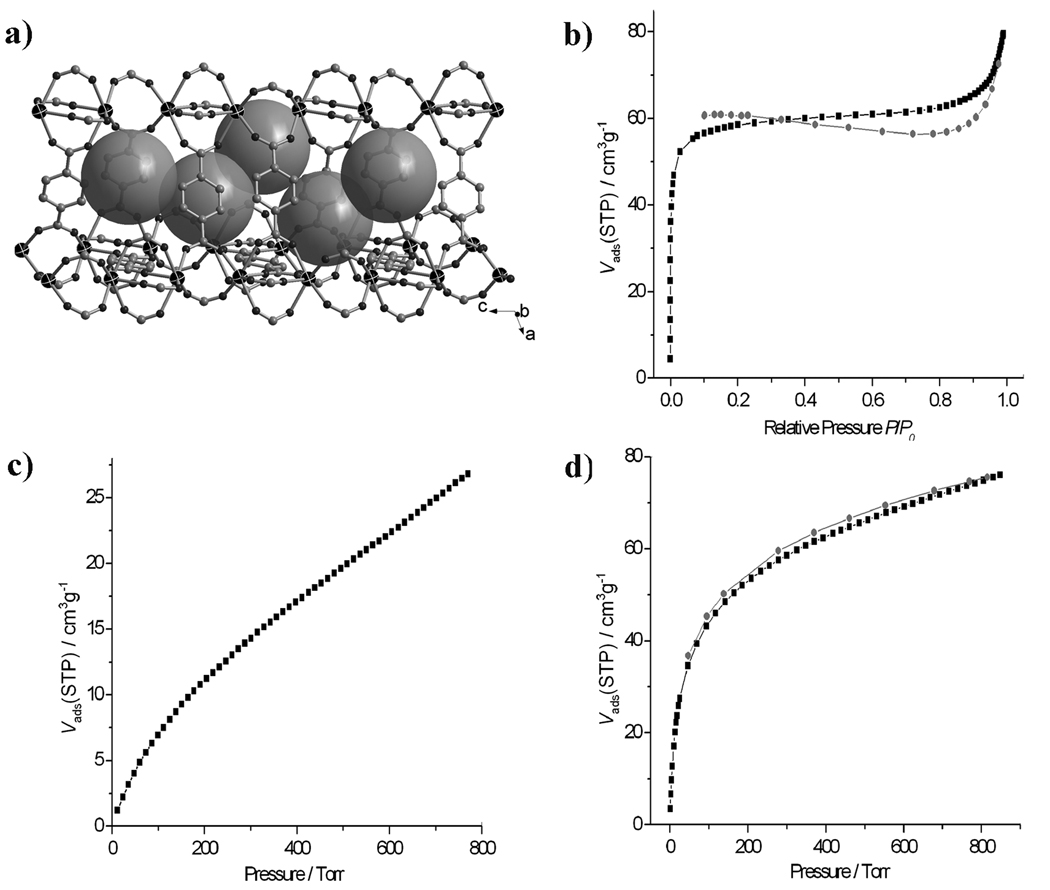

Powder X-ray diffraction further confirms that the framework [Sm(bdc)3/2]n does not change after the removal of the e-urea ligands at 300 °C (the degas temperature) and the total solvent-accessible volume is estimated to be 36.0% by using PLATON program.[11] It is worth noting that the departure of the µ2-e-urea ligand leaves two neighbouring open Sm sites (Figure 3a). It was also observed that e-urea escaped from the pore under the degas condition formed a new crystal structure at the cold end of the sample tube.[12] This suggests that the ligand is completely recyclable.

Figure 3.

The porosity (highlighted by big grey spheres) of 6 (a) and its N2 (b, P/P0 is the ratio of gas pressure (P) to saturation pressure (P0), with P0 = 769 torr), CO2(c) and H2 (d) adsorption isotherms (■adsorption; ●desorption).

Gas adsorption measurements (N2, CO2 and H2) were performed on a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 surface area and pore size analyzer, which confirms the permanent microporosity of 6. The sample was degassed at 300 °C prior to the measurement. The N2 adsorption/desorption study reveals a reversible Type I isotherm, indicating that 6 is microporous (Figure 3b). The BET and Langmuir surface areas are 186.3 and 261.5 m2/g, respectively. The pore size of 8.0 Å was also calculated.

The CO2 adsorption isotherm of 6 at 273 K exhibits the adsorption of 26.8 cm3·g−1 at ~1 atm (Figure 3c). It is worth noting that an increasing uptake is accompanied with an increase in pressure and the adsorption capacity does not saturate at 1 atm. Therefore, the uptake of CO2 is expected to continue to increase at higher pressure.

The H2 adsorption isotherm of 6 indicates an uptake of 74.9 cm3·g−1 (0.66 wt%) at 77 K and 1 atm (Figure 3d). Similar to the adsorption of CO2, the hydrogen adsorption isotherm does not reach a plateau at 1 atm. Thus, a higher hydrogen uptake is expected under higher pressures. Although the hydrogen uptake is lower than many reported porous frameworks, the use of DES as a synthetic method to generate porosity and open metal sites represents a new approach for the creation of porous metal-organic frameworks with potential applications in gas storage.

In summary, we report here four different structure-directing roles of deep eutectic solvents, leading to ten different materials with six distinct topologies. Using compound 6, we demonstrate the high thermal stability, permanent porosity, and promising gas storage capabilities of such materials. Of particular interest is that the synthetic method described here provides a versatile path for the creation of porosity and open metal sites, allowing the synthesis of porous materials with potential applications in gas storage and catalysis. Also worth noting is the role of urea-type ligands, ethylene urea in this case, which templates the framework formation and yet can leave the pore with any decomposition, leaving behind permanent porosity and open metal sites.

Experimental Section

Synthesis

The deep eutectic solvents (choline chloride/urea, choline chloride/m-urea and choline chloride/e-urea) were synthesized by heating the mixture of choline chloride and urea (m-urea or e-urea) in the 1:2 ratio at 120 °C for 20 minutes.

(a) (Choline)[InCl(bdc)3/2(H2O)2]·H2O (1)

1,4-Benzenedicarboxylic acid (H2bdc, 0.0887 g, 0.53 mmol), 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2] octane (DABCO, 0.0622 g, 0.55 mmol) and In(NO3)3·xH2O (0.0846 g, 0.21 mmol) in choline chloride/urea (2.03 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 120 °C for 5 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 1 were obtained.

(b) (Choline)[Yb(bdc)2(urea)] (2)

H2bdc (0.0943 g, 0.57 mmol), DABCO (0.0747 g, 0.67 mmol) and Yb(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1108 g, 0.24 mmol) in choline chloride/urea (2.172 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 120 °C for 5 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 2 were obtained. Compound 2a and 2b can be obtained under the similar conditions by using Sm(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1289 g, 0.29 mmol) or Y(NO3)3·xH2O (0.0982 g, 0.26 mmol) instead of Yb(NO3)3·xH2O.

(c) [Nd(bdc)2(Choline)]·(m-urea) (3)

H2bdc (0.087 g, 0.52 mmol), DABCO (0.071 g, 0.66 mmol) and Nd(NO3)3·xH2O (0.101 g, 0.23 mmol) in choline chloride/m-urea (2.30 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 140 °C for 6 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 3 were obtained.

(d) Gd2(bdc)3(m-urea)4 (4)

H2bdc (0.083 g, 0.50 mmol), DABCO (0.060 g, 0.51 mmol) and Gd(NO3)3·xH2O (0.115 g, 0.24 mmol) in choline chloride/e-urea (2.30 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 140 °C for 6 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 4 were obtained.

(e) Yb2(bdc)3(e-urea)4 (5)

H2bdc (0.0883 g, 0.53 mmol), DABCO (0.0724 g, 0.66 mmol) and Yb(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1118 g, 0.24 mmol) in choline chloride/e-urea (2.20 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 120 °C for 4 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 5 were obtained. Compound 5a and 5b can be obtained under the similar conditions by using Dy(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1102 g, 0.23 mmol) or Ho(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1232 g, 0.24 mmol) instead of Yb(NO3)3·xH2O.

(f) Sm(bdc)3/2(e-urea) (6)

H2bdc (0.1601 g, 0.99 mmol), DABCO (0.0980 g, 0.84 mmol) and Sm(NO3)3·xH2O (0.1922 g, 0.46 mmol) in choline chloride/e-urea (3.50 g) were placed in a 20 ml vial. The sample was heated at 140 °C for 5 days, and then cooled to room-temperature. After washed by ethanol and distilled water, the colorless crystals of 6 were obtained (0.195g, 0.41 mmol, Yield: 88%). CCDC-707671-707680 (1–6) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank the support of this work by NIH (X. B. 2 S06 GM063119-05) and NSF(P. F.). X. B is a Henry Dreyfus Teacher Scholar and P. Y. is a Camille Dreyfus Teacher Scholar.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jian Zhang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry California State University, Long Beach 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach, CA 90840

Tao Wu, Department of Chemistry University of California, Riverside, CA 92521.

Dr. Shumei Chen, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry California State University, Long Beach 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach, CA 90840

Prof. Dr. Pingyun Feng, Department of Chemistry University of California, Riverside, CA 92521

Prof. Dr. Xianhui Bu, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry California State University, Long Beach 1250 Bellflower Boulevard, Long Beach, CA 90840.

References

- 1.a) Jhang P-C, Yang Y-C, Lai Y-C, Liu W-R, Wang S-L. Angew. Chem. 2009;121:756. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:742–745. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Del Popolo MG, Voth GA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:1744. [Google Scholar]; c) Wasserscheid P, Keim W. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:3926. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001103)39:21<3772::aid-anie3772>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:3773. [Google Scholar]; d) Antonietti M, Kuang D, Smarsly B, Zhou Y. Angew. Chem. 2004;116:5096. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Cooper ER, Andrews CD, Wheatley PS, Webb PB, Wormald P, Morris RE. Nature. 2004;430:1012. doi: 10.1038/nature02860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Parnham ER, Morris RE. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1005. doi: 10.1021/ar700025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Parnham ER, Morris RE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2204. doi: 10.1021/ja057933l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lin Z, Slawin AMZ, Morris RE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4880. doi: 10.1021/ja070671y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Drylie EA, Wragg DS, Parnham ER, Wheatley PS, Slawin AMZ, Warren JE, Morris RE. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:7985. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:7839. [Google Scholar]; f) Parnham ER, Drylie EA, Wheatley PS, Slawin AMZ, Morris RE. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:5084. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4962. [Google Scholar]; g) Lin Z, Wragg DS, Morris RE. Chem. Commun. 2006:2021. doi: 10.1039/b600814c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Morris RE. Chem. Commun. 2009 doi: 10.1039/b902611h. DOI: 10.1039/B902611H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Férey G. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:191. doi: 10.1039/b618320b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Surbl S, Millange F, Serre C, Dren T, Latroche M, Bourrelly S, Llewellyn PL, Férey G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14889. doi: 10.1021/ja064343u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Forster PM, Eckert J, Chang J-S, Park S-E, Férey G, Cheetham AK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:1309. doi: 10.1021/ja028341v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Latroche M, Surblé S, Serre C, Mellot-Draznieks C, Llewellyn PL, Lee J-H, Chang J-S, Jhung SH, Férey G. Angew. Chem. 2006;118:8407. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:8227. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai R, Sun M, Chen Z, Munoz R, O'Neill C, Beving DE, Yan Y. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:535. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:525. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Tsao C-P, Sheu C-Y, Nguyen N, Lii K-H. Inorg, Chem. 2006;45:6361. doi: 10.1021/ic0603959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sheu CY, Lee SF, Lii KH. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:1891. doi: 10.1021/ic0518475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liao J-H, Wu P-C, Bai YH. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2005;8:390. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Jin K, Huang X, Pang L, Li J, Appel A, Wherland S. Chem. Commun. 2002:2872. doi: 10.1039/b209937n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Dybtsev DN, Chun H, Kim K. Chem. Commun. 2004:1594. doi: 10.1039/b403001j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Chen S, Bu X. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:5514. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5434. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Abbott AP, Capper G, Davies DL, Rasheed RK, Tambyrajah V. Chem. Commun. 2003:70. doi: 10.1039/b210714g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Abbott AP, Boothby D, Capper G, Davies DL, Rasheed RK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9142. doi: 10.1021/ja048266j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinca M, Long JR. Angew. Chem. 2008;120:6870. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6766. and references herein. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Blatov VA, Shevchenko AP, Serezhkin VN. Acta Crystallogr. 1995;A51:909. [Google Scholar]; b) Blatov VA, Carlucci L, Ciani G, Proserpio DM. CrystEngComm. 2004;6:377. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spek AL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crystal data for e-urea: C3H6N2O, Mr = 86.10, Orthorhombic, space group Fddd, a = 11.14(13) Å, b = 10.53(13) Å, c = 13.27(16) Å, V = 1557(32) Å3, Z = 16, Dc = 1.470 g/cm3, R1(wR2) = 0.1394 (0.3561) and S = 1.164 for 249 reflections with I > 2σ(I). The crystal structure of e-urea is shown in Figure S15 in the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.