Abstract

Consultations with community-based service providers in Toronto identified a lack of strong research evidence about successful community-based interventions that address the needs of homeless clients experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders. We undertook a collaborative research effort between academic-based and community-based partners to conduct a systematic evidence synthesis drawing heavily from Pawson’s realist review methodology to focus on both whether programs are successful and why and how they lead to improved outcomes. We examined scholarly and nonscholarly literature to explore program approaches and program elements that lead to improvements in mental health and substance use disorders among homeless individuals with concurrent disorders (CD). Information related to program contexts, elements, and successes and failures were extracted and further supplemented by key informant interviews and author communication regarding reviewed published studies. From the ten programs that we reviewed, we identified six important and promising program strategies that reduce mental health and, to a far lesser degree, substance use problems: client choice in treatment decision-making, positive interpersonal relationships between client and provider, assertive community treatment approaches, providing supportive housing, providing supports for instrumental needs, and nonrestrictive program approaches. These promising program strategies function, in part, by promoting and supporting autonomy among homeless adults experiencing CD. Our realist informed review is a useful methodology for synthesizing complex programming information on community-based interventions.

Keywords: Realist review, Concurrent disorder, Treatment, Community-based

Introduction

Homelessness continues to be a major social issue in North America. Recent estimates suggest that about 3.5 million adults will experience homelessness during any given year in the U.S.1,2 and that approximately 8,000 Canadians are affected by homelessness every night, a likely underestimate of the magnitude of the problem.3 Individuals with no fixed address experience worse health than the general population. They are more likely to suffer from chronic health conditions including tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and diabetes, are at greater risk for mortality, experience greater challenges accessing health care, and report more difficulties staying on medical regimens than their housed counterparts.3–5 Homeless individuals have high levels of mental illness with estimates ranging from 20% to 40% experiencing a severe and persistent psychiatric disability.6–12 Further complicating the health of the homeless is the fact that about 50–70% of homeless adults who report suffering from a mental illness also use or abuse substances.13–15 Overall, North American estimates suggest that 10–20% of the homeless population experience co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders,13,16 although some believe that the actual prevalence is far greater.17–19

Homelessness combined with concurrent mental health and substance use disorders (CDs) pose unique challenges in the treatment of adverse health conditions.20–22 Community-based health and social service organizations, because of their accessibility and range of available services, are often a preferred site for health and social needs addressed by homeless individuals.23 Given the complexities of the often chronic social and health problems facing homeless individuals, strong evidence is needed on why and how programs focused on CDs engage, retain, and successfully reduce the mental health and substance use problems of this marginalized population.

This review was undertaken as part of an academic–community partnership between research faculty and fellows in an inner city health research center and practitioners from urban community health and social organizations that serve low-income populations. A major motivating factor behind the partnership was to promote the uptake and implementation of research. A growing body of evidence suggests that use of research findings increases when stakeholders are involved early on in the research process to shape the direction and relevance of the research.24–30 In order to address a gap in knowledge regarding effectiveness of program components in community-based treatment approaches for CDs, in large part identified by our partners, we focused our review on evaluative research of CD programs for homeless adults based in urban community settings.

Treatment of concurrent mental health and substance use disorders have emerged only within the last two decades and researchers are starting to take stock of the effectiveness of existing treatments in reducing mental health and substance use problems, especially among housed populations.31 This literature, unfortunately, is characterized by poor evaluation designs, short-term follow-up, and heterogeneous interventions and populations. Several types of interventions lack sufficient evidence to determine their effectiveness such as individual counseling, family interventions, and intensive outpatient rehabilitation. Case management has been met with inconsistent findings such that conclusions about effectiveness cannot be made. Those interventions which show promise or are shown to be effective include group counseling for substance abuse, contingency management, and long-term residential programs, but the latter was based on weak evidence.31 However, the populations in these studies have largely been housed and the most effective means of treating CDs among the homeless in community settings has yet to be identified.

Systematic reviews generate strong evidence about treatments or interventions as they summarize a full body of work for particular treatment approaches and can yield useful information about average effect sizes across programs.32–34 While many systematic reviews emphasize the magnitude of program success, there is increasing focus in evidence syntheses on assessing what it is about interventions that make them work. To elucidate what program elements are linked to specific outcomes for treatment of CDs among homeless adults, we drew our methods from a realist systematic review approach. A realist review is particularly appropriate for understanding how complex programs work within particular contexts by exploring what “works for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and how.”35 More specifically, realist reviews focus on understanding why programs work by identifying underlying theoretical mechanisms while exploring the successes and failures of a particular program. By incorporating a focus on program contexts and underlying mechanisms, realist reviews are particularly valuable for complex social interventions such as those concerned with community health.

The present investigation builds on existing research partnerships with five community-based organizations in Toronto, Canada. We take advantage of Pawson’s39 “realist review approach” to answer the following questions: (1) What community treatment approaches are beneficial for homeless adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders? and (2) What is it about these programs that works (or doesn’t work)?

Method

Transdisciplinary Partnership

The Centre for Research on Inner City Health (CRICH) conducts multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary research to impact policies and practice that reduce health inequalities. CRICH involves policy and community partners early on and throughout their research as this approach has been shown to increase uptake of research findings.24–30 Through a community stakeholder assessment, CRICH identified five community health and service agencies1 that requested evidence in the area of services for concurrent mental health and substance use disorders in community settings among marginalized populations. The partnership was comprised of the community agencies and multidisciplinary CRICH faculty and research fellows2 who then worked together for a year to generate evidence on best practices to address mental health and substance use problems within community health and service organizations. This working group determined the scope of the review activities and research question and also worked together on all aspects of the project including dissemination of results.

Given the complexity of the issue in terms of treatment regimens and health and social issues facing marginalized populations, we sought to draw from methods of realist systematic review so that we could include numerous sources of data (e.g., academic and gray literature which was important to our community partners) and uncover the mechanisms by which successful programs work.

Research fellows and faculty conducted the practical steps of the research work, guided by monthly meetings with community partners. These meetings provided ample opportunity for community partners to contribute to the development of the research question, methodology, data interpretation, write-up, and overall direction of the project.

The project was approved by the research ethics board at St. Michael’s Hospital with which CRICH is affiliated.

Focusing the Research Question and Obtaining the Evidence

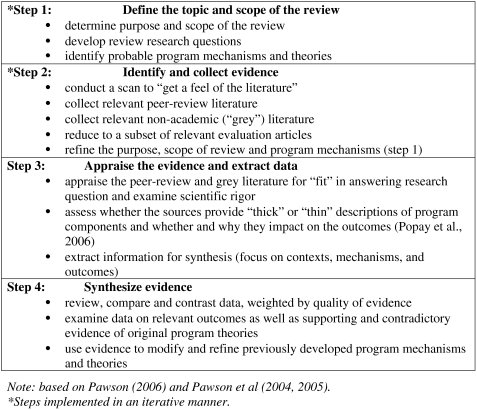

Table 1 lists the steps involved in our evidence synthesis. In keeping with the realist review approach, many of these steps were implemented in an iterative fashion.

Table 1.

Key steps involved in our systematic synthesis

Our team first identified the topic and scope of the review (step 1). Early on in our scan of the literature concerning persons experiencing mental health and substance use problems, we discovered studies about several groups of low-income populations and very heterogeneous studies and treatment approaches. Given our original interest in community-located treatment and our need to focus the population further, we decided to narrow the scope to only homeless populations as that was a common population served by all the community partners and also provided the greatest number of references. These decisions were heavily influenced by the evidence needs of our community partners who sought to improve the services they were providing to homeless persons with CDs.

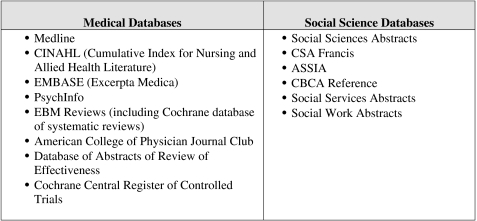

We located scholarly peer-review literature on CDs by searching relevant medical and social science databases (Table 2). All English literature since 1980 with keywords related to interventions and mental health and substance use disorders was considered.

Table 2.

Medical and social science databases

This initial search resulted in 289 citations focused on treatment programs geared for adults experiencing mental health and substance use problems. Abstracts were independently read and screened for relevance. Abstracts not focused on community-based interventions, treatment, or service programs geared specifically for adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders were excluded from the review. This primarily excluded literature on institutionalized populations, such as incarcerated or hospitalized persons and studies of veterans, as well as those that focused either on mental health or substance use disorders but not both.

Next, we read these articles in their entirety and reassessed them for relevance using the same criteria. As mentioned earlier, discussions with community partners during this phase of the research reshaped our scope to focus specifically on homeless adults experiencing concurrent mental health and substance use disorders. Fifty-seven articles focused on homeless individuals experiencing CDs. In these studies, homelessness was defined as people currently experiencing homelessness, those at risk of becoming homeless, formerly homeless (within the past few years), and underhoused people. The 17 peer-reviewed articles that were ultimately included in the review discuss ten community-based interventions geared specifically to CD clients experiencing homelessness, with evaluations assessing outcomes related to mental health or substance use disorders. In order to effectively address our research question of “what works in community-based treatment for concurrent disorders among homeless adults,” we included literature describing programs that were located in the community and incorporated a clear community integration or linkage component for clients. For example, we excluded literature on programs evaluating the effectiveness of highly structured residential treatment and therapeutic community programs, as these approaches did not actively integrate or link clients into the broader community through services, but into a smaller treatment community.

A few of the 17 articles focused on the same program; as a result, information was reviewed for each program, when appropriate. We then searched the literature and the Internet again for additional literature to ensure that we had complete information for each of the programs identified. While we made an active effort to supplement scholarly literature with gray literature, the bulk of the evidence used in this synthesis consisted of peer-reviewed research studies. We also e-mailed corresponding authors to learn more about how each program operated particularly in terms of program contexts and underlying intervention philosophies. Out of the 14 authors we contacted, ten responded to the questions we posed, including two who agreed to be interviewed over the phone. Overall, we included 38 sources of evidence on the ten programs. Figure 1 illustrates our literature search process.

FIGURE 1.

Evidence gathering.

Program Outcomes

For the purposes of this realist review, we focused on research that presented evaluative program data on outcomes related to mental health and substance use disorders among homeless clients with CDs, such as number of psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric symptom severity, number of days of substance use, and measures of substance use severity. A number of the studies also explored program effects on other nonclinical outcomes such as housing stability, educational attainment, program retention, and client satisfaction. These outcomes were of particular interest to our community partners. However, not all of the studies included an examination of the same nonclinical outcomes, making it difficult to synthesize the evidence related to these outcomes. Consequently, we chose not to synthesize data on these program outcomes for this review. We instead focused on the relationship between program components and the improvement of mental health and substance use outcomes, as this relationship was most consistently evaluated across the programs we identified.

Quality Appraisal

Quality appraisal often focuses on the methodological rigor of the study.34 While we examined methodological rigor (e.g., sample size and statistical power; presence and strength of the comparison group; use of sound outcome measures; recruitment of the sample of homeless persons), one of our main interests in assessing quality was to determine whether the study yielded information of relevance to our research questions and was “fit for purpose.”34,36–38 Even studies that were determined to be of poorer methodological quality, if they provided “trustworthy nuggets of information to contribute to the overall synthesis,”39 were kept but given a lower weight. As such, we not only assessed the strength of the evaluation presented but also examined information provided on “what works” and why. Furthermore, because some studies examined a broad range of outcomes, we assessed the portions of the study that pertained to our research questions concerning community-based interventions for homeless populations for the outcomes of mental health and substance use problems.

We appraised the quality of evidence on a case-by-case basis during the literature search, extraction, and synthesis process. For research studies, we evaluated the strength of the design components when ample information was available (e.g., statistical power, sampling strategies, strength of the comparison groups and methods of evaluation, internal and external validity). For studies that did not indicate a statistically significant difference between treatment and control conditions, we assessed the level of statistical power available in the study. We did this by employing power calculations using information on reported differences between treatment and comparison groups and the sample size available for the analyses. To assess the rigor of the evaluation design, we assessed the presence of or appropriateness and comparability of the comparison groups as well as the recruitment strategies to determine whether large sources of bias could have been introduced through these two routes.

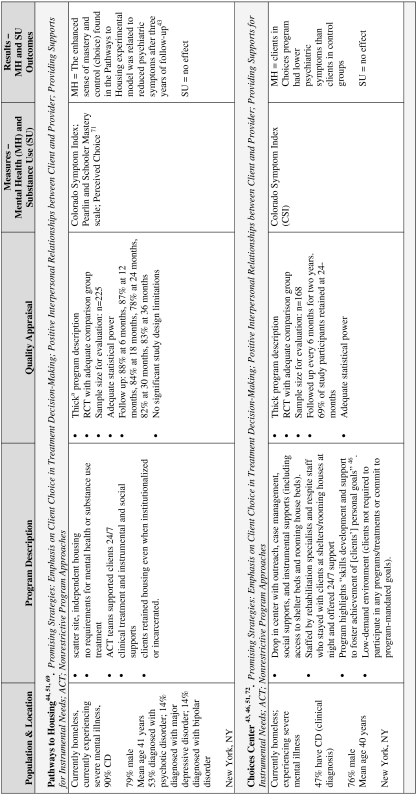

To address the quality of evidence available to determine what works and why, we considered whether the studies presented “thick” or “thin” descriptions of the program components and their mechanisms according to quality appraisal techniques developed by Popay et al.37 Thick program descriptions typically included a detailed description of the program and its suitability for the targeted population, a description of the factors that affect implementation, and a consideration of the reasons for anomalous results.36–38,40 In our case, we rated studies along the thick/thin continuum in terms of whether the studies provided information on how program components reduced mental health symptoms and/or substance use problems. Information on program components and their mechanisms was gleaned from the methods and discussion sections of scholarly literature and from companion articles describing these components of programs. Concerning assessment of the quality of evidence on program mechanisms, we tended to give greater weight to statements based on data that were collected and analyzed as part of the reviewed studies compared to statements made by authors about program workings that were supported by external literature. We used the quality appraisal to give more weight to the evidence provided by studies that had stronger methodological designs as well as provided thicker descriptions of program mechanisms. Table 3 lists information on the ten programs included in this review and details pertaining to quality appraisal.

Table 3.

Program description and quality appraisal

In instances in which study authors did not compute follow-up rates, they were calculated by dividing the number of respondents surveyed at follow-up by the total number of respondents enrolled at baseline. When not available, descriptions regarding statistical power were based on calculations computed by the authors using information on sample size available for follow-up and effect size and were computed solely for mental health and substance use outcomes

CD concurrent disorder, RCT randomized controlled trial

aProgram description also based on 51,70, personal communications with Tsemberis and Padgett, March 2008

bProgram description also based on Bebout (1999)79

cProgram description also based on Blankertz and White (1990),80 personal communication with Cnaan, March 2008

dProgram description also based on 76

Data Abstraction and Synthesis

During the initial stages of data abstraction, we focused on extracting data related to context, paying close attention to the quality of the data and what aspects and under which circumstances programs were successful or not and on identifying any failures or harms associated with programs. By reading and rereading the articles and engaging in discussion about them as a team, we sought to identify those program models that worked and the reasons for program success or failure. This textual approach to synthesizing findings and telling a story based on multiple studies, which do not exclusively focus on the effectiveness of a specific intervention, is similar to narrative synthesis.35 Initially, we grouped programs according to common approaches and common models to synthesize the evidence (e.g., assertive community treatment [ACT], case management). However, within groups of treatment models, there was much heterogeneity in overall approaches. Moreover, almost all studies implemented a combination of strategies. Thus, it was virtually impossible to isolate the effects of a particular model on our outcomes of interest. Yet, through both the synthesis process and the weighing of evidence through quality appraisal, we began to identify program components that were often present in programs that were more successful in addressing mental health and substance use outcomes. Because the evidence was not overwhelmingly and specifically supporting a particular approach, we refer to these identified program components or elements as “promising program strategies” that have the potential to improve the mental health and substance use outcomes of CD clients, as they were most commonly present in programs with greater success. As mentioned earlier, these strategies were not necessarily stand-alone program components. Rather, they were often present within the same program and appeared to work together to impact upon client mental health.

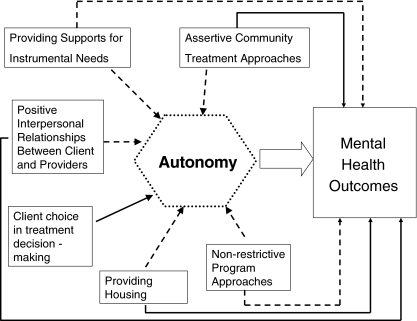

As noted earlier, the realist review approach is about identifying program mechanisms or underlying program theories. From our review, several of the program elements were thought to or could be hypothesized to promote autonomy in the client and consequently improve mental health. The relationship of the program elements to each other, to client autonomy, and to mental health outcomes are depicted in Figure 2. It should be emphasized that this conceptual framework did not emerge directly from any one study nor did any of the studies cover all the strategies contained in the figure. Rather, the studies we reviewed contributed parts of the framework with some evidence for the linkages being stronger (thus the solid arrows) than other areas (dashed arrows). Below, we present these promising program strategies, starting with those that have the strongest evidence and concluding with strategies that have not been as rigorously examined.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual framework of proposed processes facilitating improved mental health outcomes among homeless adults experiencing CDs.

Findings

Promising Program Strategies

Emphasis on Client Choice in Treatment Decision-Making

Clients served by community-based treatment programs for homeless adults with CDs that incorporated client choice in treatment and program decision-making showed improved mental health outcomes. This element was a feature in six of the ten reviewed programs. Client choice was featured prominently in Choices Center and Pathways to Housing and, to a lesser extent, in Horizon Home and Emerson–Davis programs.41 The Choices Center and Pathways to Housing programs were specifically designed to enhance clients’ sense of autonomy or mastery and control and were organized to promote clients’ priorities and interests. Called “client choice” in some programs, this feature ensured that clients’ choices would be respected, regardless of whether these choices were consistent with treatment priorities. Clients were seen as autonomous individuals, experts of their own lives, who should make their own decisions.42,43 For instance, in the Pathways to Housing program, clients chose their apartments and neighborhoods, and provision of housing was not tied, in any way, to mental health or substance use treatment. In addition to making decisions about treatment, Choices Center clients had significant input into staffing decisions and program elements resulting in a program that was maximally tailored to their own needs. Data from Pathways to Housing showed that clients’ sense of mastery and their perceived level of choice were mediators in the causal pathway between housing and psychiatric symptoms. Thus, the beneficial effect of the Pathways to Housing program and the provision of independent housing “first” on psychiatric symptoms are attributed to the enhanced sense of mastery and control that clients experience as part of their treatment.44

Positive Interpersonal Relationships Between Clients and Providers

Several of the studies reviewed highlighted the quality of interpersonal relationships between clients and providers as a promising strategy related to improved outcomes among homeless individuals experiencing CDs. Calsyn et al.45 assessed reciprocal dynamics between clients and providers and showed in their study that trusting relationships, wherein clients and providers both feel comfortable with each other, were associated with client improvement in psychiatric symptoms. One-sided client–provider relationship dynamics, where respect and dignity were shown by service providers to their clients, was an important theme that emerged from the Pathways to Housing and Choices Centre programs. Respectfulness and dignity toward clients were seen to build trust and client self-esteem, which in turn increased clients’ ability to address their life needs. Peer support staff members who had lived experience with homelessness, substance use, or mental health disorders were found to be particularly effective in the Choices program, as their experiences “increased the empathic response in staff–member relationships beyond that found with more traditional staff patterns… [and] increased sensitivity to the struggles” that clients face.46 Clients noticed the difference, stating that peer support staff “really care” and that they “know how to relate to you as an individual.”43 The findings in the Pathways to Housing program further support this, as Padgett et al.47 found that “acts of kindness” by staff made a real difference for clients mental health and helped engage and retain clients in programs. “Acts of kindness” refer to staff who “treat participants with warmth and humanity and/or made extra efforts on their behalf,” for instance, by going out of their way to provide support for clients during difficult transitions or to connect clients to instrumental supports.47 These recollections stood out for clients because such moments were rare “amidst a norm of routinized ([and] sometimes dehumanizing) encounters with staff” [in other programs].47

Assertive Community Treatment Approaches

The provision of services from an ACT approach emerged in four of the reviewed studies as a promising practice for addressing client outcomes. ACT is an approach to addressing mental health and substance use whereby treatment is delivered by a multidisciplinary team of providers. ACT is assertive, outreach-focused, and highly available in the sense that services are delivered within the community and are available to clients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.48 Furthermore, many of the ACT programs reviewed incorporated an “integrated ACT” approach in which mental health and substance use treatment are offered in the same program location as opposed to at different agencies48–50 and do not require clients to be abstinent in order to enter the program.50,51 Meisler et al.50 and Essock et al.49 found that an ACT approach was related to reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations (but not mental health symptoms) among CD clients over time. Choices Center and Pathways to Housing also used this approach and their programs had positive outcomes for mental health. Such improved outcomes may be facilitated by the fact that this approach is available at all hours of the day and night to clients in order to meet their needs. However, only one of these studies yielded modest evidence to support the effectiveness of such an approach at reducing substance use problems over time.50 There is, thus, minimal evidence indicating the utility of an ACT approach for improving substance use outcomes among homeless individuals experiencing CD.

Despite the fact that several of the ACT programs delivered clinical services in an integrated manner, only one group of studies, Morse et al.48, specifically examined the effect of “integrated ACT” on mental health and substance use outcomes.48 The authors found no difference between the integrated ACT vs. nonintegrated ACT for mental health or substance use outcomes. The authors argued that lack of fidelity in the implementation of the ACT program models may have led to treatment diffusion in which the experimental groups may have received similar types of programming. Based on the data available in this review, it was not possible to establish the superiority of integrated treatment services within an ACT framework for homeless individuals with CD.

Providing Housing

The provision of housing, along with other services, is an important element in the treatment of homeless persons with CDs; however, the evidence is difficult to synthesize as the definition of “housing provision” and the types of “housing” provided differed greatly among studies. One of the more successful programs, Pathways to Housing, offered independent, scatter-site housing without requirements to attend treatment or to be abstinent. This approach may serve to build client self-esteem and autonomy. Having a safe place to stay where one is not at imminent risk of physical danger or expulsion by authorities and where one is not required to live by the strict rules of a shelter allows for greater independence, greater choice, and an enhanced sense of autonomy. This is supported by the concept of “ontological security,” the “well-being that arises from a sense of constancy in one’s social and material environment which, in turn, provides a secure platform for identity development and self-actualization.”52–54 Dupuis and Thorns’ definition of ontological security includes the condition that home is where “people feel in control of their lives,”54,55 providing further support for housing and independent housing as a promising strategy. While the ACCESS program did not provide clients with independent housing directly, it is suggestive of the positive effect that independent housing can have, as clients who were independently housed showed more significant decreases in substance use than clients who were unstably housed or living in shelters or institutions. Horizon Home, which yielded reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations and higher abstinence rates, housed clients in a supervised group home.

Programs that provided other models of housing also reported positive effects on clients’ mental health and/or substance use. For example, both the Community Connections and Emerson–Davis programs followed a “continuum of housing” approach in which clients were first placed into supportive group living arrangements and gradually moved to less restrictive and more independent types of housing as their recovery progressed. As previously discussed, because these programs did not focus exclusively on provision of housing, it is not possible to attribute improvements to provision of housing alone.

The level of structure within housing programs can influence substance use and/or mental health outcomes. For instance, the program discussed by Burnam et al.56 placed clients into monitored group homes, enforced strict rules, and demanded sobriety.56 The program evaluation found no support for this model in terms of reducing mental health and substance use problems. Burnam et al.56 speculated that their high demand environment and strict rules contributed to the lack of program success. However, none of the reviewed programs specifically examined the independent contribution or rules surrounding housing, so future research in this area is warranted.

Providing Supports for Instrumental Needs

The provision of supports beyond just mental health and substance use treatment, either directly or through referral, emerged as a promising strategy in three of the programs reviewed. The programs that emphasized meeting clients’ needs beyond mental health and substance use treatment tended to make positive gains in substance use and mental health, although there were no evaluative studies that tested the unique effect of this program component. For example, the Pathways to Housing program takes a holistic approach to caring for clients in that their services are not limited to housing support and mental health and substance use treatment, but rather include additional supports such as recreation rehabilitation, money management, community integration, and advocacy. Similarly, the Choices program aimed to meet all of the clients’ needs by providing comprehensive supports including social support, storage lockers, meals, and showers, in addition to clinical care and shelter housing. Finally, the Emerson–Davis Family Development Center Program also embraced a comprehensive treatment approach by addressing legal and family needs, in addition to providing clinical support for mental health and substance use issues. Programs that prioritize assistance with clients’ immediate needs (e.g., food, clothing, personal hygiene, social support) may free clients to work on needs that are less immediate, such as mental health or substance use.

Nonrestrictive Program Approaches

Nonrestrictive, flexible program policies also emerged as a promising strategy in a few of the reviewed programs. For example, in some programs, abstinence was not a requirement for program entry or retention.43,50,51 In the Pathways to Housing program, there is no predetermined end time to treatment. This program follows the “once a client, always a client” philosophy where treatment, housing, and support are offered unconditionally regardless of the clients’ situations. Such a flexible approach is respectful to clients needs and provides stability, consistency, and control as they progress through the program. In contrast, the community-linked residential program discussed by Burnam et al.56 consisted of a relatively short, 3-month intensive treatment period after which clients moved to less intense services. The authors reflected that the short-term nature of the intervention may have contributed, in part, to the lack of success since mental health and substance use problems are typically chronic issues requiring longer-term management and intervention.56

Discussion

In this review of studies on community-based interventions, we drew heavily from the realist review methodology. We learned about program mechanisms from both successful and nonsuccessful programs and by augmenting the evaluative evidence in the studies with information gleaned from “thick” program descriptions and communications with those who implemented and evaluated these programs.

We identified ten distinct community-based or community-linked programs serving homeless individuals experiencing CDs that employed a variety of approaches including ACT, provision of housing, integrated mental health and substance use treatment, and a holistic approach through which many of the clients’ life needs were supported. Most programs delivered a combination of program strategies or took different approaches to the same strategies (e.g., different models of housing provision in Pathways to Housing vs. Community Connections and different degrees of fidelity to the ACT model between programs). There was significant heterogeneity across studies in program approaches and measurement as well as methodological weaknesses in some studies, such as no or weak comparison groups and high attrition over time. These limitations hampered our ability to generate strong evidence describing best practices in the treatment of CDs for homeless individuals. These methodological limitations reflect, in large part, the challenges of studying and following up hard to reach populations such as homeless individuals.

A key component of the realist review is building and uncovering a theory of how the program works—the “mechanism” of the program.39 Through a review of the available evaluative and descriptive evidence and despite the limitations noted above, we identified six promising program strategies for the improvement of CDs. These promising strategies included an emphasis on client choice in treatment decision-making, positive interpersonal relationships between client and provider, ACT approaches, providing independent housing along with other services, providing services beyond mental health and substance use treatment, and nonrestrictive program approaches. Because many of the programs incorporated more than one promising strategy, often delivered in different combinations between programs, we cannot identify one promising strategy as being better than the others.

These promising program strategies showed greater impact upon improvements in mental health outcomes than for substance use problems. Our synthesis suggested pathways by which the six program strategies may exert their effects on improvements in mental health, as presented in Figure 2. In the figure, those pathways that were supported by stronger evidence are indicated by solid arrows while the dashed lines indicate weaker evidence. As suggested by the figure, some strategies were found to have a direct impact on improving mental health such as providing clients with independent housing and positive client–provider relationships characterized by trust. These strategies as well as others such as client choice in program decision-making or providing supports for instrumental needs may work to reduce mental health symptoms by promoting client autonomy. Autonomy or the ability to be self-directed has been strongly linked to improvements in problematic health and other behaviors such as successful diabetes management, long-term weight loss, long-term smoking cessation, positive behavior change among troubled and troubling youth, and even nonhealth issues such as law school performance and satisfaction.57–60 Many of the studies identifying autonomy as a central factor in motivation for and maintenance of behavior change noted that goals which are self-directed vs. goals that are imposed or controlled by external sources (e.g., health care providers) are not only more likely to be attained but that goals imposed from external sources may negatively impact well-being.59 Thus, programs and program strategies that support autonomy and self-determination in treatment and use of services will likely lead to longer-term positive health changes compared to programs that are fixed and are restrictive in content and in modes of administration.61 Figure 2 illustrates possible pathways by which these promising strategies may directly impact mental well-being and also build clients’ sense of autonomy and control over their lives and ultimately lead to mental health improvements. Client autonomy appears to be a promising and perhaps essential component of community-based programs and should not only be considered and studied when initiating new projects, but also more rigorously evaluated in those programs where this model of care currently exists. It would be particularly important to know whether and how client autonomy is best promoted for clients with different types of mental health problems and illnesses.

The studies we reviewed provided weak evidence concerning what works for improving substance use outcomes. A lack of improvement in substance use problems has been reported in prior reviews of research on the effectiveness of case management programs for clients with CDs.31 The lack of improvement in substance use problems that we observed across some studies we reviewed may have been due, in part, to a narrow focus on abstinence as the outcome (e.g.,41). Clients, as well as providers, may experience or observe reduction in or greater control of substance use, but such improvements would have been missed when abstinence measures are used. Future studies might consider adopting measures that incorporate a harm reduction perspective on substance use which would capture more nuanced changes in substance use.

A limitation of our review was the quality of evidence presented in the programs that we reviewed, suggesting that too few evaluations had strong internal validity or yielded “thick” descriptions of program elements. The research design of some of the evaluation studies had considerable methodological limitations. For example, a number of the program evaluation studies did not have a comparison group and/or were statistically underpowered to detect the differences yielded by the interventions. We attempted to gain further information about the program theories or mechanisms as well as to obtain insights into why programs were or were not successful by obtaining qualitative program description information from supplementary literature or by communicating with the corresponding and lead authors of the studies we reviewed. Only a few studies undertook qualitative investigations into program implementation and program workings and we were successful in obtaining such information in too few instances. Thus, many of our studies ended up being thin on descriptions of what works, for whom and why.

An additional limitation is that we focused on only two outcomes, mental health and substance use. However, given the complex health and social needs of homeless clients experiencing CD, a number of other outcomes, some of which were examined in the studies reviewed, also deserve further systematic study. For example, nonclinical client outcomes such as short-term and long-term housing stability, short-term and long-term employment and educational attainment, and program-related outcomes such as retention and client satisfaction all deserve further research attention in order to adequately identify the best interventions to meet the needs of clients. Furthermore, our community partners specifically identified a need for research attention to the effects of cultural sensitivity, harm reduction programming, and discharge planning on outcomes.

We sought to implement a method of synthesizing the research evidence that is appropriate for complex interventions and that the identification of best or promising practices for treating homeless clients in community-based or community-linked settings who have concurrent mental health and substance use problems. We drew heavily from the realist review approach promoted by Pawson.35,39,62,63 We had too little guidance on how to actually implement a realist review as there are few examples, and the examples provide sparse information on their methods. For example, Connelly conducted a realist systematic review of obesity prevention programs but provided no detailed information about how their synthesis addressed the issue of uncovering program mechanisms.64 Greenhalgh and colleagues65 synthesized evidence from an existing systematic review to identify potentially successful program mechanisms but did not supplement with descriptive studies or gray literature which, as the authors note, could have enhanced their review. It is still in the early stages in terms of the implementation of realist systematic reviews and our synthesis contributes to the small but growing set of reviews following a realist approach. Because we were interested in employing the best method for synthesizing the evidence on this complex intervention, we were guided not only by the published and available examples of realist reviews64–66 and texts on realist evaluation and review approaches,35,62–66 but also from literature concerning review approaches appropriate for complex interventions.34,37,67,68

Contextual factors, including the characteristics and circumstances of individuals as well as the cultural climate in which programs and systems are operating, are considered important components of describing theories in a realist review and reviews of complex programs.37,39,65 Notwithstanding our intentions to incorporate contextual factors into the synthesis process, much of the literature was lacking in thick descriptions of population characteristics such as ethnicity, as well as the setting or cultural environment in which programs were being implemented, thus presenting further challenges around quality assessment. Given the complexity of CDs, particularly among marginalized populations, it is crucial that future research addresses the context and cultural setting in which programs are operating, so that such complex needs can be effectively met.

A strength of our review lies in the continuous involvement of community-based agencies in various stages of the research process. While experience and expertise from the community partners was key in the integration of knowledge, the evidence gathering process, as well as the extraction and synthesis phases, we were particularly motivated to retain involvement of these key stakeholders to maximize the chances that the evidence will be used to change or inform current practice or policy.24–30

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Strategic Training Initiative in Health Research grant (STO-64598), the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, and the Alma and Baxter Ricard Chair in Inner City Health (PO). We would like to thank the following individuals who participated in the research activities: Gladis Chow, Susan Clancy, Jessica Hill, Axelle Janczur, Erika Khandor, Kelly Murphy, Rosane Nisenbaum, Lynne Raskin, Anjali Sharma, Janet Smylie, Melissa Tapper, Charoula Tsamis, Qamar Zaidi, Carolyn Ziegler, and Marcqueline Chiona Zulu.

Footnotes

Community agencies forming the partnership with CRICH: Access Alliance; Ontario Federation of Indian Friendship Centres; Sistering, a Women’s Place; Street Health; South Riverdale Community Health Centre.

CRICH faculty and research fellows had expertise in the following areas: social epidemiology, biostatistics, clinical psychology, sociology, family medicine, aboriginal health, ethics, public health sciences, knowledge translation, and social work.

References

- 1.National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. Homelessness in the United States and the Human Right to Housing; 2004.

- 2.Urban Institute. A New Look at Homelessness in America. Available from the Urban Institute, 2100 M Street, N.W., Washington, DC, 20037 or available at: http://www.urban.org.

- 3.Hwang SW. Homelessness and health. Can Med Assoc J. 2001; 164(2): 229-233. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.National Coalition for the Homeless 2006a. Health Care and Homelessness NCH Fact Sheet #8. Available at: http://www.nationalhomeless.org. Accessed on June, 1 2008.

- 5.Street Health. The Street Health Report. Available at: http://www.streethealth.ca/Downloads/SHReport2007.pdf.

- 6.Lehman AF, Cordray DS. Prevalence of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among the homeless: one more time. Contemp Drug Probl. 1993; 20: 355-383.

- 7.National Coalition for the Homeless 2006b. Mental Illness and Homelessness NCH Fact Sheet #5. Available at: http://www.nationalhomeless.org. Accessed on June, 1 2008.

- 8.National Resource and Training Center on Homelessness and Mental Illness 2003. Get the Facts. Available at: http://www.nrchmi.samhsa.gov. Accessed on June, 1 2008.

- 9.Smith EM, North CS, Spitznagel EL. A systematic study of mental illness, substance abuse, and treatment in 600 homeless men. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1992; 4: 111-120. [DOI]

- 10.Toro PA, ed. Homelessness. New York: Pergamon; 1998. Bellack AS, Hersen M, eds. Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, Ch. 8 in Vol. 9, Applications in diverse populations (pp. 119–135).

- 11.Toro PA, Wall DD. Research on homeless persons: diagnostic comparisons and practice implications. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1991; 22(6): 479-488. [DOI]

- 12.Toro PA. Toward an international understanding of homelessness. J Soc Issues. 2007; 63(3): 461-481. [DOI]

- 13.Drake RE, Osher FC, Wallach MA. Homelessness and dual diagnosis. Am Psychol. 1991; 46(11): 1149-1158. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. J Am Med Assoc. 1990; 264: 2511-2518. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. Report to Congress on the Prevention and Treatment of Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC; 2003.

- 16.Buckner JC, Bassuk E, Zima B. Mental health issues affecting homeless women: implications for intervention. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1993; 63(6): 385-399. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Drake RE, Yovetich NA, Bebout RR, Harris M, McHugo GJ. Integrated treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997; 185(5): 298-305. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Eberle M, Kraus D, Serge L, Pomeroy S, Hulchanski D. Homelessness—Causes and Effects. Victoria: Ministry of Social Development and Economic Security and BC Housing Management Commission; 2001.

- 19.Serge L, Kraus D, Goldberg M. Services to Homeless People with Concurrent Disorders: Moving Towards Innovative Approaches. Vancouver, Canada: 2006.

- 20.Gelberg L, Linn LS, Usatine RP, Smith MH. Health, homelessness and poverty. A study of clinic users. Arch Int Med. 1990; 150: 2325-2330. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Goering P, Pyke J, Bullock H. Health, Mental Health, and Addiction Treatment Needs of People Using Emergency Shelters in Toronto. City of Toronto; 2004.

- 22.Goering P, Tolomiczenko G, Sheldon T, Boydell K, Wasylenki D. Characteristics of persons who are homeless for the first time. Psychiatr Serv. 2002; 53: 1472-1474. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.O’Toole TP, Gibbon JL, Hanusa BH, Fine MJ. Preferences for sites of care among urban homeless and housed poor adults. J Gen Intern Med. 1999; 14(10): 599-605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Denis JL, Lomas J. Convergent evolution: the academic and policy roots of collaborative research. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003; 8(Suppl 2): 1-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dobrow MJ, Goel V, Upshur RE. Evidence-based health policy: context and utilisation. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 58(1): 207-217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Graham ID, Logan L, Harrison M, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006; 26: 13-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Innvaer SGV, Trommald MAO. Health policy-makers’ pecrceptons of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002; 7: 239-244. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Jacobson N, Butterill D, Goering P. Development of a framework for KT: understanding user context. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003; 8(2): 94-99. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Landry R, Lamari M, Amara N. Extent and determinants of utilization of university research in government agencies. Publ Admin Rev. 2003; 63(2): 193-205.

- 30.Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside J, McLeodm C, Abelson J. Knowledge Transfer Research Group. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Q. 2003; 81: 171-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Drake RE, O’Neal EL, Wallach MA. A systematic review of psychosocial research on psychosocial interventions for people with co-occurring severe mental and substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008; 34(1): 123-138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Dixon-Woods M, Agaral S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005; 10(1): 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005; 10(1): 6-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell; 2006.

- 35.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review: a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005; 10(S1): 21-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004; 13: 223-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster: Institute for Health Research, Lancaster University; 2006.

- 38.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, Dillon L. Quality in Qualitative Evaluation: A Framework for Assessing Research Evidence. London, UK; 2003.

- 39.Pawson R. Evidence-Based Policy: A Realist Perspective. London: Sage; 2006.

- 40.Arai L, Roen K, Roberts H, Popay J. It might work in Oklahoma but will it work in Oakhampton? Context and implementation in the effectiveness literature on domestic smoke detectors. Inj Prev. 2005; 11: 148-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Blankertz LE, Cnaan RA. Assessing the impact of two residential programs for dually diagnosed homeless individuals. Soc Serv Rev. 1994; 68: 536-560. [DOI]

- 42.Cnaan RA, Blankertz L, Messinger KW, Gardner JR. Psychosocial rehabilitation: toward a definition. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1988; 11(4): 61-77.

- 43.Lovell AN, Cohen M. The elaboration of “choice” in a program for homeless persons labeled psychiatrically disabled. Human Organ. 1998; 57(1): 8-20.

- 44.Greenwood R, Schaefer-McDaniel N, Winkel G, Tsemberis SJ. Decreasing psychiatric symptoms by increasing choice in services for adults with histories of homelessness. Am J Community Psychol. 2005; 36(3/4): 223-238. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Calsyn RJ, Morse GA, Klinkenberg WD, Lemming MR. Client outcomes and the working alliance in Assertive Community Treatment programs. Care Manage J. 2004; 5(4): 199-202. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Anthony W, et al. Serving street-dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2000; 90(12): 1873-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Padgett DK, Henwood B, Abrams C, Davis A. Engagement and retention in care among formerly homeless adults with serious mental illness: voices from the margins. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008; 31(3): 226-233. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg WD, et al. Treating homeless clients with severe mental illness and substance use disorders: costs and outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2006; 42(4): 377-403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Essock SM, Mueser KT, Drake RE, et al. Comparison of ACT and standard case management for delivering integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006; 57: 185-196. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Meisler N, Blankertz L, Santos AB, McKay C. Impact of assertive community treatment on homeless persons with co-occurring severe psychiatric and substance use disorders. Community Ment Health J. 1997; 33(2): 113-122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Tsemberis S, Moran L, Shinn B, Shern D, Asmussen S. Consumer preference programs for individuals who are homeless and have psychiatric disabilities: a drop-in center and a supported housing program. Am J Community Psychol. 2003; 32(3/4): 305-317. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Giddens A. Consequences of Modernity. Oxford: Polity; 1990.

- 53.Laing RD. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. London: Pelican; 1965.

- 54.Padgett DK. There’s no place like (a) home: ontological security among persons with serious mental illness in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 64: 1925-1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Dupuis A, Thorns DC. Home, home ownership, and the search for ontological security. Socio Rev. 1998; 46(1): 24-47. [DOI]

- 56.Burnam MA, Morton SC, McGlynn EA, et al. An experimental evaluation of residential and nonresidential treatment for dually diagnosed homeless adults. J Addict Dis. 1995; 149(4): 111-134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Harper E. Making good choices: how autonomy support influences the behavior change and motivation of troubled and troubling youth. Reclaiming Children and Youth. 2007; 16(3): 23-28.

- 58.Miquelon P, Vallerand R. Goal motives, well-being, and physical health: an integrative model. Can Psychol. 2008; 49(3): 241-249.

- 59.Ryan R, Deci E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000; 55(1): 68-78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Williams G, Gagne M, Mushlin A, Deci E. Motivation for behaviour change in patients with chest pain. Health Educ. 2005; 106(4): 304-321. [DOI]

- 61.White KR. The transition from victim to victor: an application of the theory of mastery. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1995; 33(8): 41-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage; 1997.

- 63.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist Synthesis: An Introduction. ESRC Research Methods Programme Working Paper Series. UK: University of Manchester; 2004.

- 64.Connelly J, Duaso M, Butler G. A systematic review of controlled trials of interventions to prevent childhood obesity and overweight: a realistic synthesis of the evidence. Publ Health. 2007; 121: 510-517. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson ERV. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programs. BMJ. 2007; 335: 858-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Pawson R. Does Megan’s Law Work? A Theory Drive systematic Review. ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice: Working Paper 8. London; 2002.

- 67.Egan M, Bambra C, Petticrew M, Whitehead M. Reviewing evidence on complex social interventions: appraising implementation in systematic reviews of the health effects of organisational-level workplace interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009; 63: 4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Herbert R, Bo K. Analysis of quality of interventions in systematic reviews. BMJ. 2005; 331(3): 507-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004; 94(4): 651-656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Padgett D, Gulcur L, Tsemberis S. Housing first services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Res Soc Work Pract. 2006; 16(1): 74-83. [DOI]

- 71.Srebnik D, Livingston J, Gordon L, King D. Housing choice and community success for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. Community Ment Health J. 1995; 31(2): 139-152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Winarski J, Cope N, Cohen M, Anthony W. The effectiveness of psychiatric rehabilitation for persons who are street dwelling with serious disability related to mental illness. In: In Breakey WR, Thompson JW, eds. Mentally Ill and Homeless. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 1997: 119-147.

- 73.McHugo GJ, Bebout RR, Harris M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of integrated versus parallel housing services for homeless adults with severe mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2004; 30(4): 969-982. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Essock SM, Frisman LK, Kontos NJ. Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment teams. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998; 68(2): 179-190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Essock SM, Kontos N. Implementing assertive community treatment teams. Psychiatr Serv. 1995; 46: 679-683. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Stecher BM, Andrews CA, McDonald L, et al. Implementation of residential and non-residential treatment for the dually diagnosed homeless. Eval Rev. 1994; 18(6): 689-717. [DOI]

- 77.Anonymous. Supportive residential services to reunite homeless mentally ill single parents with their children. Psychiatr Serv. 2000; 51(11): 1433–1435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. One-year housing arrangements among homeless adults with serious mental illness in the ACCESS program. Psychiatr Serv. 2004; 55(5): 566-574. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Bebout RR. Housing solutions. The community connections housing program: Preventing homelessness by integrating housing and supports. Alcohol. Treat Q. (1999); 17(1): 93-112. [DOI]

- 80.Blankertz L, White KK. Implementation of rehabilitation program for dually diagnosed homeless. Alcohol. Treat Q. (1990); 7(1): 149-164. [DOI]