Abstract

A field study of supported employment for adults with mental illness (N=174) provided an experimental test of cognitive dissonance theory. We predicted that most work-interested individuals randomly assigned to a non-preferred program would reject services and lower their work aspirations. However, individuals who chose to pursue employment through a non-preferred program were expected to resolve this dissonance through favorable service evaluations and strong efforts to succeed at work. Significant work interest-by-service preference interactions supported these predictions. Over two years, participants interested in employment who obtained work through a non-preferred program stayed employed a median of 362 days versus 108 days for those assigned to a preferred program, and participants who obtained work through a non-preferred program had higher service satisfaction.

Rehabilitation and prevention programs operate in a natural marketplace in which organizational success depends on favorable participant attitudes. Any program can enhance its chance of success by conducting community surveys to estimate the prevalence of service-related interests and needs prior to implementation (Heller & Patterson, 2006; Hendryx, Beigel, & Doucette, 2001; Macias, DeCarlo, Wang, Frey, & Barreira, 2001; Uehara, Srebnik, & Smukler, 2003). Since new risk prevention, skill training, employment, education, and wellness programs are often sponsored by existing community agencies, and offered by multi-service programs within these agencies, intervention success also depends on public attitudes toward these umbrella programs. If a new service is offered by a program most people would prefer to avoid, enrollment is likely to be low, regardless of how much the community needs that particular service (Corrigan & Salzer, 2003; Macias et al., 2005). This is an obvious conclusion to any service planner. However, it is not so obvious what might happen if a large number of individuals reluctantly pursued a needed service through a non-preferred program. Would their half-hearted participation compromise both individual success and overall program effectiveness?

Dissonance Theory Predictions

The theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957; Festinger & Aronson, 1960; Harmon-Jones & Mills, 1999) states that when people freely choose to act in a way that is inconsistent with their attitudes, beliefs, or preferences, they will be motivated to reduce this inconsistency, either by rationalizing their behavior or by changing their subjective opinions to more closely match their behavior (Aronson, 1999; Aronson & Mills, 1959; Dickerson, Thibodeau, Aronson, & Miller, 1992; Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959; Gonzales, Aronson, & Costanzo, 1988; Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, 2002; Nel, Helmreich, & Aronson, 1969). For instance, individuals who refuse needed services because they are offered by a program they do not want to join can easily resolve the dissonance between service need and behavior by rationalizing that these services really were not so important to their welfare after all. On the other hand, individuals who choose to enroll in a non-preferred program to fulfill personal goals can rationalize the discrepancy between preference and behavior by believing that the program will help them reach their goals. For this rationalization to remain credible, the individual must then actively pursue service-related goals. Ironically, voluntary enrollment in a non-preferred program should increase consumer motivation and improve service outcomes.

These dissonance theory ideas are especially applicable to community programs that depend on consumer initiative because cognitive dissonance is more intense when an individual perceives a contradiction between personal attitudes and voluntary actions (Harmon-Jones, 2003; Stone, 1999). Individuals who are court-mandated to participate in a non-preferred program do not have to rationalize their behavior because compliance is already reasonable. By contrast, individuals who voluntarily enroll in a service program are behaviorally expressing an interest in the services offered and their intent to pursue service-related goals. In the case of community programs with very practical aims (employment, education, housing, skill training), voluntary enrollment also reflects an intent to exert considerable effort toward reaching a particular goal. For instance, supported employment programs are designed to help disabled adults find work, so enrollment represents an implicit agreement to initiate a job search and accept a paying job.

Ordinarily, interest in work should increase the likelihood of service receipt and employment (Macias et al., 2001). The exception to this rule would be work-interested participants assigned to a non-preferred program (Hypothesis 1). Participants disappointed in their program assignment are likely to reject the services offered (Macias et al., 2005), and this decision not to pursue opportunities for employment will be dissonant with their intent to find work. To resolve this dissonance, they will tend to conclude that employment is not worth program participation, and, accordingly, reduce their work aspirations. By contrast, individuals who decide to pursue supported employment offered by a non-preferred program should tend to adopt the opposite rationale -- employment is well worth the effort. However, the rationalization “I enrolled just to get a job” remains credible only if the individual makes a strong effort to find and keep a job, and if she believes that the program deserves partial credit for her work success. Accordingly, (Hypothesis 2) individuals who choose to participate in a non-preferred program in order to find employment should end up more committed to their jobs than other program participants, working longer and earning more. In keeping with their expectation that program participation will be efficacious, (Hypothesis 3) individuals who become employed after enrolling in a non-preferred program should also report greater satisfaction with services than other program participants.

Study Overview

These three research hypotheses were generated in 1996 and then tested using data collected from 1996–2001 for a NIH-funded service evaluation that compared two widely-disseminated but distinctly different models of psychiatric rehabilitation, a program of assertive community treatment (Stein & Test, 1980) versus a certified clubhouse (Beard, 1978). Both programs offered identical supported employment, which, at that time, was a relatively new intervention for adults with severe mental illness. The study randomized participants to service programs, so each participant was also randomly matched or mismatched to her program preference, providing an experimental test of the three dissonance theory hypotheses.

Method

Service Programs

The program of assertive community treatment (PACT; Allness & Knoedler, 1998) is an intensive mobile treatment team composed of nurses, social workers, substance abuse specialists, and a part-time psychiatrist, in addition to an employment specialist in the vocationally-integrated version of the model (Frey, 1994; Russert & Frey, 1991). The vocationally-integrated PACT in this study was created in Worcester, Massachusetts, by Leonard Stein, M.D. and Jana Frey, Ph.D. of Madison, Wisconsin. Fidelity to the model was verified through annual site visits by Dr. Frey.

A clubhouse (Anderson, 1998) is a facility-based day program offering membership in a supportive community composed of both members (consumers) and staff. A defining aspect is the 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM “Work-Ordered Day” in which members and staff work side by side to perform voluntary work essential to the clubhouse (Beard, Propst, & Malamud, 1982). The clubhouse in this study was Genesis Club, Inc. in Worcester, Massachusetts, which was certified by the International Center for Clubhouse Development as having full compliance with the Standards for Clubhouse Programs (Propst, 1992).

In both programs, vocational specialists trained in the same methods of supported employment (Bond et al., 2001; Trach, 1990) worked closely with other staff to ensure rapid placement of consumers into mainstream jobs not reserved for persons with disabilities. Services provided on an as-needed basis included interest and skill assessments, counseling, help with job searches, resume and interview preparation, transportation planning, negotiation of job accommodations, on-the-job training, and on-site mentoring or conflict mediation.

Participants

Project enrollment was limited to unemployed adults over age 18 who had DSM-IV diagnoses of serious mental illness (schizophrenia spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, or recurrent severe depression) and lacked a diagnosis of severe mental retardation (IQ > 70). Out of 177 total enrollees, three were lost to follow-up. The final sample of project participants (N=174) was heterogeneous (Jones et al., 2004) and similar to epidemiological samples of adults with serious psychiatric disabilities within the same state (Dembling, Chen, & Vachon, 1999; Dickey, Normand, Weiss, Drake, & Azeni, 2002). Except for gender, sample characteristics (Table 1) were distributed comparably across participants interested and not interested in work, and across participants mismatched and not mismatched to their pre-enrollment program preference.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who were randomly mismatched or not mismatched to program preferencea

| Interested in work at baseline (n=121) |

Total sample (N=174) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mismatch to program preference (n=30) | No Mismatch to preference (n =91) | Mismatch to program preference (n=47) | No Mismatch to preference (n =127) | |||||

| Characteristic | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % | M (SD) | % |

| Male gender* | 40 | 64 | 43 | 59 | ||||

| Caucasian | 80 | 84 | 79 | 79 | ||||

| Baseline age | 36.70 (11.02) | 38.36 (9.99) | 37.81 (11.10) | 38.17 (9.89) | ||||

| Schizophrenia diagnosis | 57 | 51 | 51 | 52 | ||||

| Psychiatric symptomsb | 45.04 (6.36) | 46.35 (7.77) | 44.60 (7.17) | 46.58 (8.86) | ||||

| Physical health problemsc | 5.93 (3.72) | 6.50 (3.26) | 6.26 (3.37) | 6.35 (3.29) | ||||

| Substance use disorder | 27 | 41 | 26 | 39 | ||||

| Baseline level of functioning (poor or fair)d | 57 | 66 | 66 | 68 | ||||

| High school diploma | 63 | 60 | 66 | 64 | ||||

| Standard job in five years preceding study | 60 | 56 | 62 | 56 | ||||

| Random assignment to PACTe | 47 | 54 | 38 | 53 | ||||

Random assignment to program that was not preferred versus random assignment to the preferred program or no program preference

Mean total score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale across all administrations, with positive, negative, and general subscales equally weighted. Possible scores range from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

Estimated annual costs of non-psychiatric medical treatment (measures of severity) were log transformed

Self-rating on single Likert scale item with response options of ‘poor,’ ‘fair,’ ‘good,’ or ‘excellent.’

Random assignment to a program of assertive community treatment (PACT) or certified clubhouse modeled on Fountain House, New York.

Work interest only: experimental groups differed significantly (p<.05) on gender within a chi square analysis.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from 42 agencies and advocacy groups in Worcester, Massachusetts, and self-referrals were elicited through flyers, radio announcements, and newspaper advertisements. Recruiters and posters described the project as an evaluation of supported employment services offered by two multi-service programs, but emphasized that enrollees could enroll for reasons other than work and would not be pressured to get jobs. Recruiters also explained that enrollees would be expected to slowly relinquish any current service that duplicated services provided through the project. Because only one of the two service programs (PACT) provided clinical services, and only the other (clubhouse) offered daily activities, this rule against duplication of services helped to shape individual program preferences. Although applicants reluctant to exchange current services for new ones enrolled in the project at a lower rate than those who reported no such reluctance (37%, n=26 versus 63%, n=151; χ2=15.57, df=1, p<.001), the final sample of enrollees had just as many participants who wanted to avoid exchanging a current day program for the clubhouse (7%; n=13) as to avoid exchanging current clinical services for PACT (7%; n=13). Overall, just as many project enrollees preferred the clubhouse (24%; n=43) as preferred PACT (25%; n=45).

During private intake sessions, interviewers read a description of the study aloud, explained randomization, recorded the applicant’s program preference, if any, and then asked each applicant if she would be willing to participate fully in whichever of the two programs she was randomly assigned, regardless of personal preference. If the applicant expressed understanding and agreed to participate, she signed a written informed consent, completed the baseline interview, and then received her service assignment. Participants were given the telephone number, address, and a contact name for the assigned program, and the program was likewise notified. Participant program contact was then tracked through program records and six-month interviews conducted by research staff. All procedures and materials were approved by the McLean Hospital IRB.

Measures

Interest in Work

Behavioral intent (Ajzen, 1996; Gollwitzer, 1996) was measured by asking “Are you currently interested in working?” during the baseline interview conducted prior to randomization. A response was coded “1” if the participant reported interest in getting a job, or “0” if she did not want to work or was uncertain.

Program Preference

Program preferences were recorded verbatim during intake interviews, content-coded as ‘pro-PACT,’ ‘pro-clubhouse,’ or ‘no expressed preference,’ and then recoded after random assignment as ‘match to preference,’ ‘mismatch to preference,’ or ‘no prior preference.’ To test the study hypotheses, we focused on ‘mismatch to service preference,’ with ‘match to preference’ and ‘no prior preference’ as a combined ‘not mismatched’ reference group.

Employment Status

Employment outcomes for this study included all jobs lasting at least five days that met the U.S. Department of Labor’s definition of competitive employment: mainstream, integrated work paying at least minimum wage (Department of Labor, 1998). Transitional employment jobs, which were owned by the clubhouse, met these federal criteria, but were not counted as outcomes in this comparative study.

Duration of Employment

Duration of employment was measured as both calendar days employed during each participant’s first 24 months in the project, and as calendar days employed during the 24 months following first day of work. The timeframe for the first analysis was March 1996 (earliest enrollment) through May 2000 (latest follow-up date); the timeframe for the second analysis was June 1996 (earliest job) through May 2001 (latest follow-up date).

Service Satisfaction

Satisfaction with assigned program was measured as each individual’s mean score (1, poor; 4, excellent) on the last-administered 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (Attkisson & Greenfield, 2004) during a 30-month follow-up period. For most participants, this was the 30-month (n=113) or 24-month (n=21) interview. For the remaining 15 percent with available data, it was from the 18-month (n=14), 12-month (n=2), or 6-month (n=7) interview. Participants with no service satisfaction data (N=17) moved out of area (n=8), died (n=3), or were unable or unwilling to participate in research interviews (n=6). There was no missing data for the focal ‘work interest-by-non-preferred program-by-employed’ condition, but more clubhouse than PACT participants were lost to follow-up (n=12 vs. 5).

Service Program Assignment

We statistically controlled for differences in program effectiveness (Macias et al., 2006) when testing our dissonance theory hypotheses. Comparable percentages of work interested, preference mismatched participants were randomly assigned to each program (PACT: 47%; clubhouse: 53%).

Service Receipt

Total job search hours provided by each program (logged) and receipt of one hour or more of employment services while employed (1 yes, 0 no) were statistically controlled in the analyses of work rates and work duration, respectively. Total days of direct service contact was controlled in the analysis of service satisfaction. Contact frequency and vocational support were highly correlated, so were not included together in any analysis. Daily service logs were kept by both programs from January 1996 through December 2001.

Background Characteristics

We controlled for gender and any disorder other than severe mental illness that might limit job qualifications, restrict work performance, or account for differences in program effectiveness (Macias et al., 2006). Each participant was coded as either (1) having no work-restrictive co-occurring disorder or (0) as having current treatment-documented severe substance dependence, a life-threatening (e.g., AIDS, lung cancer) or chronic (e.g., heart disease, morbid obesity, amputation) health problem, or as older than age 50 at baseline.

Quality of Life Improvements Attributable to Employment

Any change in quality of life could influence a participant’s perception of service quality, so baseline quality of life was controlled in the analysis of service satisfaction, along with the mean of all subsequent scores. Subjective life quality was measured as each individual’s mean rating (1, terrible, to 7, delighted) on Lehman’s Brief Quality of Life Scale (Lehman, Kernan, & Postrado, 1997). Scores for employed participants were averaged across all interviews conducted between first day of employment and 24-month project anniversary. Scores for unemployed participants were averaged across all interviews conducted between 6 and 24 months after project enrollment.

Analysis Plan

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted with SPSS (Version 10) (“SPSS for Windows,” 1999). Conceptually similar variables were entered simultaneously to control for multiple tests, and no statistically significant variable or interaction term was interpreted unless the omnibus test for that variable block was also significant (p<.05). In keeping with standard practice (Cohen & Cohen, 1983), participant background variables were entered first, followed by program assignment, and then predictor variables. We expressed hypotheses as interactions between dichotomous predictor variables coded to represent specific sample groups (Aiken & West, 1991; Blanton & Jaccard, 2006). For the analyses of employment rates (N=174) and work duration (N=79), participants who expressed interest in work and were randomly assigned to a non-preferred program served as the focal group. For the analysis of service satisfaction (N=157), the focal group included participants interested in work assigned to a non-preferred program who became employed. In keeping with study hypotheses, we expected the focal groups to have lower work rates, but longer work duration and higher service satisfaction.

Post hoc analyses were conducted to rule out alternative explanations. In this field study, dissonance was generated by idiosyncratic behaviors and spontaneous reflection not amenable to interview reports. We inferred that work interested participants assigned to a non-preferred program had experienced dissonance if there were no other reasonable interpretation of the pattern of findings predicted by dissonance theory (APA Taskforce, 1999; Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, & Gonzales, 1990; McGuire, 1999; Rindskopf, 2000).

Results

Hypothesis 1: Assignment to a non-preferred program for supported employment will reduce the chance that participants interested in work will become employed

The significant ‘work interest-by-assignment to non-preferred program’ interaction in the logistic regression analysis of employment rates (Table 2) supports this dissonance theory hypothesis. Although baseline work interest was a positive predictor of employment for most people, work interest decreased the chances of becoming employed when a work-interested participant was randomly assigned to a non-preferred program. The unemployment rate for work-interested participants assigned to a non-preferred program (63%) was substantially higher than the unemployment rate for work-interested participants who were assigned to their preferred program or who had no program preference (39%), and nearly as high as the unemployment rate for participants who had expressed no interest in work (77%).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis predicting employment status during first 24 months in project (N=174)a

| Variables | B | SE B | Odds | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: control variablesb | ||||

| Gender (male) | .08 | .31 | 1.08 | .802 |

| No co-occurring disorders subgroup | .04 | .31 | 1.04 | .900 |

| Block 2: experimental service variablesc | ||||

| Program (clubhouse) | −1.15 | .49 | .32 | .018 |

| Clubhouse-by-no co-occurring disorders | 1.26 | .66 | 3.54 | .057 |

| Job search services (logged hours) | .27 | .07 | 1.31 | .001 |

| Block 3: predictor variablesd | ||||

| Baseline work interest | 1.40 | .41 | 4.06 | .001 |

| Assignment to non-preferred program | −.31 | .40 | .73 | .443 |

| Block 4: work interest-by-non-preferred programe | −2.08 | .87 | .13 | .017 |

Model: X2=46.27, df=8, p<.001.

Block 1: X2=.09, df=2, p=ns. No co-occurring disorders: combined very psychiatrically ill and relatively healthy groups, 1.

Co-occurring disorders: combined chronically physically ill, very physically ill, and severe substance disorder groups, 0.

R2 improvement when service variables are added to control variables: X2=27.03, df=3, p<.001. Certified clubhouse, 1; program of assertive community treatment (PACT), 0.

R2 improvement when predictor variables are added to previously entered variables: X2=13.46, df=2, p<.01. Work interest, 1; no work interest or uncertain, 0. Non-preferred program, 1; preferred program or no preference, 0.

Improvement in R2 when focal interaction term is added to previously entered variables: X2=5.69, df=1, p<.02.

Tests of assumptions

Previously published findings demonstrate that assignment to a non-preferred program generally lowered service participation (Macias et al., 2005). An auxiliary analysis reveals that this finding held true only for work-interested individuals. Among participants not interested in work, service preference had no discernable impact on service engagement (p=ns). By contrast, participants interested in work who were not mismatched to their program preference had more frequent service contact (n=91, M=127, SD=119, Md=108 contact days) than work interested participants mismatched to their program preference (n=30, M=64, SD=77, Md=49 days), whose service contact was nearly comparable to that of participants not interested in work (n=53, M=90, SD=106, Md=48), F=4.42, df=2, 171, p<.05. These findings support the dissonance theory assumption that participants initially interested in work who were disappointed in their service assignment reduced their employment aspirations and efforts to find a job to justify low participation in the non-preferred program.

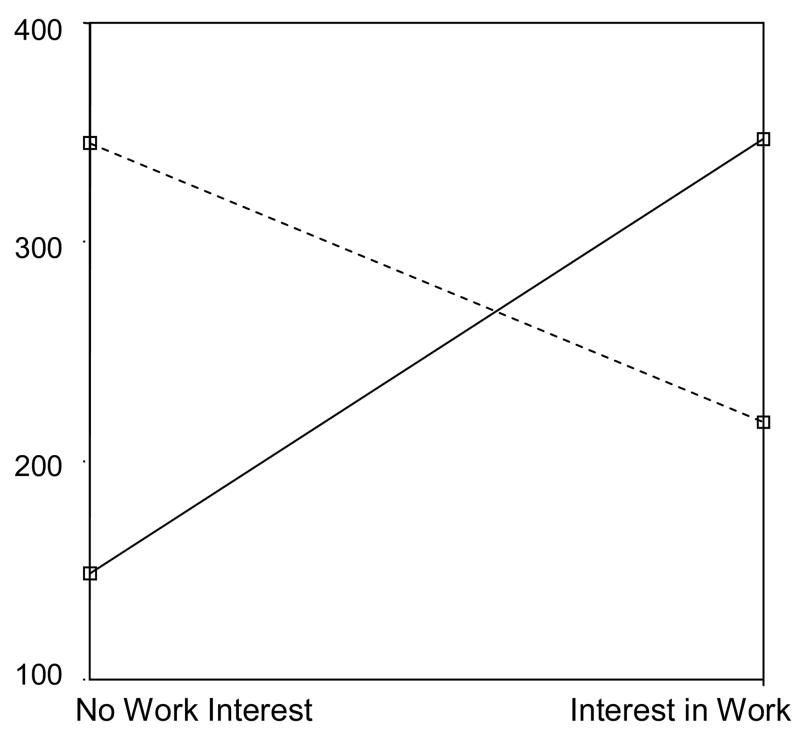

Hypothesis 2: Participants interested in work who find employment through a non-preferred service program will stay employed longer than other participants

The significant ‘work interest-by-assignment to non-preferred program’ interaction terms in both work duration analyses (Table 3) support this dissonance theory hypothesis. As Figure 1 illustrates, work-interested participants assigned to a program they did not want remained employed a mean of 347 days (median=362) after starting their first job, compared to a mean of 218 days (median=108) for work-interested participants not mismatched to their program preference. The reverse was true for employed participants who did not have an initial interest in work, whose employment was briefer if they were assigned to a non-preferred program. Apparently, participants who enrolled in a non-preferred program to find work came to view job success as a strong personal goal.

Table 3.

Regression analyses predicting total days employed over 24 months (N=79)a

| Days employed in 24 months following project enrollment | Days employed in 24 months following first day of first job | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE B | p | B | SE B | p |

| Block 1: control variablesb | ||||||

| Gender (male) | −.25 | .26 | .335 | −.27 | .26 | .318 |

| No co-occurring disorders subgroup | .13 | .26 | .605 | .08 | .26 | .762 |

| Block 2: experimental service variablesc | ||||||

| Program (clubhouse) | −.27 | .38 | .478 | −.37 | .38 | .334 |

| Clubhouse-by-no co-occurring disorders | 1.16 | .50 | .025 | 1.48 | .50 | .005 |

| On-job supported employment services | .36 | .26 | .172 | .45 | .26 | .084 |

| Block 3: predictor variablesd | ||||||

| Baseline work interest | .16 | .39 | .677 | .11 | .38 | .773 |

| Assignment to non-preferred program | .17 | .34 | .619 | .18 | .34 | .593 |

| Block 4: Work interest-by-non-preferred programe | 1.89 | .73 | .012 | 2.26 | .72 | .002 |

Models (df=8, 70): 24 months after enrollment, R2=.19, adj R2=.10; F=2.11, p<.05; 24 months after job, R2=.27, adj R2=.19; F=3.24, p<.01 Total days employed was log-transformed for both analyses.

Block 1 (df=2, 76): 24 months after enrollment, R2=.02, F=.57, p=ns; 24 months after first job, R2=.01, F=.53, p=ns.

R2 improvement when service variables (df=3, 73) are added to control variables: 24 months after enrollment, R2=.10, F=2.72, p=.05; 24 months after first job, R2=.15, F=4.36, p<.01. Certified clubhouse, 1; program of assertive community treatment (PACT), 0.

On-job support services: at least one hour of supported employment services while employed.

R2 improvement when predictor variables (df=2, 71) are added to all previously entered variables: 24 months after enrollment, R2=.01, F=.16, p=ns; 24 months after job, R2=.01, F=.15, p=ns

R2 improvement when focal interaction (df=1. 70) is added to all previously entered variables: 24 months after enrollment, R2=.08, F=6.62, p<.02; 24 months after first job, R2=.10, F=9.90, p<.01.

Figure 1.

Mean days of employment after start of first job (N=79)

Random assignment to non-preferred program ________

Random assignment to preferred program or no program preference __ __ __

Tests of assumptions and alternative explanations

Our assumption that participants interested in work were predisposed to view program participation as a means-to-an-end receives support from the concurrent finding that employed participants received more job search services than other participants (Table 2), and from a previously published finding from the same data showing that this was true of work interested, employed participants in particular (Macias et al., 2006). Apparently, a means-to-an-end attitude provided a practical rationale for participating in a non-preferred program, --a rationale that could be affirmed through sustained work.

When mean hourly pay is added to both work duration regression models (not in table), this variable significantly improves adjusted R2 and predicts work duration, but the ‘work interest-by-assignment to non-preferred program’ interaction remains significant as well, with minimal change in beta, indicating that fiscal incentives contribute to work duration, but do not account for the predicted cognitive dissonance effect.

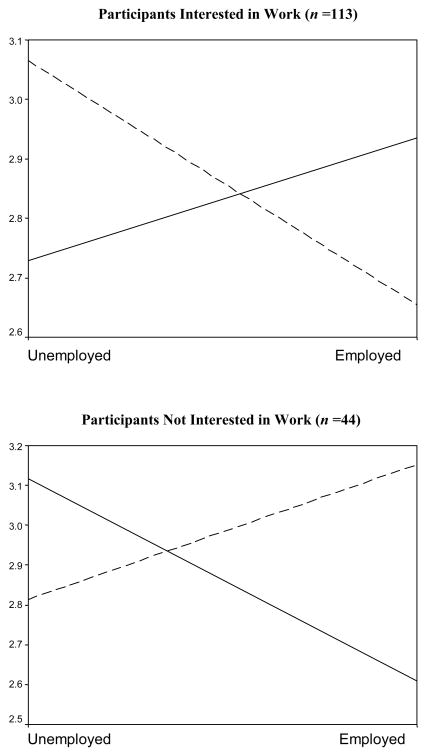

Hypothesis 3: Participants interested in work who find employment through a non-preferred service program will have higher service satisfaction than other participants

This dissonance theory prediction is supported by the three-way ‘work interest-by-assignment to non-preferred program-by-employed’ interaction in the regression analysis of service satisfaction (Table 4). As Figure 2 shows, work-interested participants assigned to a non-preferred program were more satisfied with program services if they were employed rather than unemployed. By contrast, work-interested participants assigned to a preferred program, and those who had no program preference, were less satisfied with their assigned services if they became employed. An opposite pattern of findings was obtained for participants who expressed no interest in work when they enrolled in the project: Participants assigned to a preferred program and those with no program preference were more satisfied with services if they were employed, whereas participants assigned to a non-preferred program were more satisfied if they remained unemployed, as they had originally intended.

Table 4.

Regression analyses predicting satisfaction with assigned services at final research interview (N=157)a

| Variables | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: control variablesb | |||

| Gender (male) | .10 | .13 | .447 |

| No co-occurring disorders subgroup | −.29 | .13 | .031 |

| Block 2: experimental service variablesc | |||

| Program (clubhouse) | .38 | .14 | .010 |

| Service contact days in first 24 months | .19 | .05 | .001 |

| Block 3: subjective quality of lifed | |||

| Baseline quality of life | −.01 | .09 | .991 |

| Mean quality of life during first 24 months | .28 | .10 | .004 |

| Block 4: predictor variablese | |||

| Baseline work interest | −.03 | .15 | .829 |

| Assignment to non-preferred program | −.02 | .14 | .920 |

| Employed in first 24 months | −.19 | .14 | .173 |

| Block 5: 2-way lower-order interactions f | |||

| Work interest-by-non-preferred program | −.18 | .31 | .562 |

| Employed-by-non-preferred program | .18 | .30 | .544 |

| Employed-by-work interest | −.16 | .33 | .630 |

| Block 6: focal 3-way interactiong | |||

| Work interest-by-non-preferred program-by-employed | 1.46 | .65 | .025 |

Model: R2=.26, adj R2=.19; F=3.85, df=13, 143, p<.001

Block 1: R2=.03, F=2.54, df=2, 154, p=.08

R2 improvement when service variables in block 2 are added to control variables: R2=.10, F=8.70, df=2, 152, p<.001

Certified clubhouse, 1; program of assertive community treatment (PACT), 0. Program-by-no co-occurring disorders interaction: p=ns.

R2 improvement when quality of life variables are added to previously entered variables: R2=.08, F=8.00, df=2, 150, p<.001

R2 improvement when predictor variables are added to previously entered variables: R2=.01, F=.76, df=3, 147, p=ns.

R2 improvement when lower order interactions are added to previously entered variables: R2=.01, F=.35, df=3, 144, p=ns

R2 improvement when focal interaction is added to all other variables: R2=.03, F=5.11, df=1, 143, p<.05

Figure 2.

Mean service satisfaction scores (N=157)

Tests of assumptions and alternative explanations

By statistically controlling for self-ratings of life quality following start of first job, we ruled out the possibility that the longer employment of participants in the focal work-interest, non-preferred program condition improved service satisfaction simply because work improved satisfaction with life in general. Participants omitted from this analysis because they had no service satisfaction score (n=17) had less service contact than participants with data (t=2.53, df=1, 172, p<.02), and were less likely to become active in their assigned program (61% vs. 89%, p<.01), but these biases would reduce the predicted dissonance theory effect, so missing data does not threaten our interpretation of findings.

The high service satisfaction of participants in the dissonance condition (work interest, non-preferred program, employed), and their relatively long service retention (median of 21 out of 24 months), suggest that these participants pursued employment to improve their lives, rather than to avoid program participation. On the other hand, the relatively low service satisfaction of work-interested participants who remained unemployed after assignment to a non-preferred program is congruent with our assumption that rejection of employment services leads to disinterest in work.

Discussion

Study findings support the common-sense notion that consumers assigned to a non-preferred community intervention program will tend to refuse services and have less favorable outcomes than participants not mismatched to their program preference, but the findings also uncover an important exception to this general rule. Consumers who voluntarily enroll in a non-preferred program to achieve personal aims tend to have better outcomes and greater service satisfaction than other consumers, including those who favored their program assignment. These dissonance theory findings suggest simple advice for consumers who are offered needed services through a disfavored program: View program services as a means-to-the-end of your own choosing. This self-affirming strategy (Aronson, Cohen, & Nail, 1999) has the added advantage of increasing the chance of personal success and, hence, program effectiveness.

New research is needed to determine why some work-interested individuals assigned to a non-preferred program lowered their work aspirations and avoided the assigned services, while others rationalized their counter-attitudinal intent and pursued supported employment. We need to find out what makes one dissonance reduction strategy more appealing than another in a natural service setting (Leippe & Eisenstadt, 1999). Participants who withdrew may have done so to sidestep the emotional overload they anticipated from counter-attitudinal behavior (Keller & Block, 1999; Suedfeld & Epstein, 1971). Or they may have shared a perspective or personality trait (e.g., low need for consistency) that predisposed them to trivialize both their program assignment and their interest in work (Michel & Fointiat, 2002).

Practical Significance

What is most remarkable about these dissonance theory findings is the practical, observable benefits of cognitive dissonance, even in seemingly small doses. Cognitive inconsistency (irrationality) may be a particularly strong concern for adults with severe mental illness. However, recent evaluations of dissonance theory-based interventions for eating disorders also show strong and practical benefits (e.g., weight, eating habits, body image) of counter-attitudinal behavior for young women who do not have psychoses or disabling depression (Becker, Smith, & Ciao, 2006; Mitchell, Mazzeo, Rausch, & Cooke, 2007; Stice, Presnell, Gau, & Shaw, 2007). Any rating scale score (e.g., self-image, service satisfaction) holds relative, not absolute, meaning, but both the eating disorder studies and the present study also report observable life improvements attributable to dissonance reduction. In the present study, temporal differences in work duration between dissonance conditions represent several months in the lives of adults with severe psychiatric disabilities, a population that is highly unlikely to sustain paid work (Baron & Salzer, 2002; Catalano, Drake, Becker, & Clark, 1999; Rosenheck et al., 2006).

It is also surprising that employed participants in the dissonance condition ended up so pleased with their non-preferred program up to two years after dissonance was first generated. It may be that continued counter-attitudinal participation in program services that were not designed to promote work (e.g., group activities in the clubhouse; counseling or help with daily living in PACT) generated additional dissonance because it clashed with their ‘enrolled just to get a job’ rationale for program participation (Joule & Azdia, 2003). If these two programs had specialized in supported employment, we might have seen less service satisfaction for participants in the dissonance condition (Beavous & Joule, 1999).

Potential Moderators

The practical implications of our study findings would be more valuable to service planners if we could identify situational and trait variables that strengthen or weaken individual efforts to reduce the dissonance generated by counter-attitudinal behavior. This was a field experiment in which the timing and intensity of the dissonance experience was highly idiosyncratic, and potential moderators of the dissonance effects were, likewise, idiosyncratic and heterogeneous. Moderator variables assumed to be present to varying degrees in the present study include the extent to which program participation would be a voluntary action (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, 2002), public (Festinger & Aronson, 1960), or aversive (Cooper, 1999; Harmon-Jones, 2000; Harmon-Jones, Brehm, Greenberg, Simon, & Nelson, 1996), as well as whether the actor viewed the dissonant situation as culturally relevant (Kitayama, Snibbe, Markus, & Suzuki, 2004; Norton, Cooper, Monin, & Hogg, 2003) and whether she had low, high, or fragile self-esteem (Jordan, Spencer, Zanna, Hoshino-Browne, & Correll, 2003; Martinie & Fointiat, 2006; Nail, Misak, & Davis, 2004; Stone, 2003) or access to positive self-attributes that could buffer dissonant cognitions (Stone, 1999; Stone & Cooper, 2003).

In general, clubhouse participation was more public than PACT and more dependent on individual initiative, whereas PACT was more assertive and controlling, making withdrawal from PACT more difficult. Participants were randomly assigned to these two programs, and to preference ‘mismatch’ and ‘no mismatch’ experimental conditions, with sample subgroups generally comparable in demographics and personal histories (Table 1), so we would not expect subgroup differences in cultural beliefs or personality traits (e.g., self-esteem, need for consistency, sensitivity to public opinion). Moreover, participation in a non-preferred program cannot be assumed to be consistently aversive, since reasons for not wanting to be assigned to either PACT or clubhouse were diverse (e.g., rumors, stigma, requirement to relinquish a competing service) and being ‘mismatched to preference’ sometimes reflected only disappointment in not being assigned to the alternative program.

While any of these moderator variables, or combination of variables, may have intensified or minimized cognitive dissonance for a particular participant, only anticipated or actual voluntary action (Harmon-Jones & Harmon-Jones, 2002) was a defining aspect of the ‘mismatch to preference’ dissonance condition. All project enrollees were forced into an action orientation when they agreed to accept randomization and participate in whichever program they were assigned. Those assigned to a non-preferred program were then confronted by an expectation to voluntarily perform a counter-attitudinal behavior. If they chose to pursue their assigned services, this action orientation remained strong and salient. However, while an action orientation may have been a necessary condition for the generation of cognitive dissonance (Harmon-Jones, 1999), it may not have been sufficient in every circumstance. Considering the wide array of moderator variables under consideration, it is possible that at least one other moderating variable was present for every participant, and this additional motivation may have been essential in many instances (Aronson et al., 1999; Baumeister & Tice, 1984), as when dissonance was reduced through perseverance in paid work (Pittenger, 2002).

Study Limitations

We relied on sample representativeness and program fidelity to generalize findings from this evaluation of two prominent service models (Macias et al., 2006). Sample size was restricted to the number of clients typical of each program, so the research sample was too small to test moderation hypotheses. Larger-scale risk prevention studies offer more feasible tests of higher-order interactions. We also do not know if our specific findings apply to other types of community programs or to service populations in different geographical locations. Replication, even with this same population, was impractical because this typical psychiatric service randomized trial spanned several years and data collection cost $2.5 million.

We encourage other community program evaluators to conduct conceptual replications (Aronson et al., 1990; Lewin, 1944) by routinely measuring participants’ program preferences, and motivation to pursue service-related goals, prior to randomization. The present study demonstrates the strong impact of consumers’ pre-existing attitudes on service outcomes, so the inclusion of these two baseline measures as standard covariates in comparative evaluations should increase internal validity and further a conceptual understanding of service effectiveness. More sophisticated attitudinal measures could be devised or adopted, but simple dichotomous self-reports appear to be reliable enough to produce significant group differences, and their inherent face validity allows a straight-forward presentation of findings to stakeholders and policymakers.

Conclusions

Apparently, service effectiveness is as dependent on consumer motivation, and the situational contingencies that enhance or reduce personal motivation, as on the actual capacity of a program to improve individual lives (Chen & Rossi, 1992; Hedrick, Bickman, & Rog, 1993; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). We gain a deeper understanding of program effectiveness when we incorporate consumer self-determination in our evaluation designs as a causal variable on par with intervention services. Since cognitive dissonance is an ordinary life experience that is resolved through reflective self-determination, our study findings are also a reminder of the inherent rationality of people with severe psychiatric disabilities when faced with important life decisions. It is time to reconceptualize what it means to ‘intervene’ in their lives.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an interdisciplinary research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH-62628), and was part of the multi-project Employment Intervention Demonstration Program (EIDP) funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SM-51831). Supplemental support was provided by the van Ameringen Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, and the University of Massachusetts Medical School. No author, affiliated institution, or funding organization has a conflict of interest. The authors thank their NIMH project monitor, Ann Hohmann, Ph.D., for her helpful insights and encouragement.

Contributor Information

Cathaleene Macias, Community Intervention Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA

Elliot Aronson, Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Cruz

William Hargreaves, Department of Psychiatry, University of California Medical School, San Francisco

Gifford Weary, Department of Psychology, Ohio State University

Paul J. Barreira, Community Intervention Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA

John Harvey, Department of Psychology, University of Iowa

Charles F. Rodican, Community Intervention Research, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA

Leonard Bickman, Center for Mental Health Policy Vanderbilt University

William Fisher, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The directive influence of attitudes on behavior. In: Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA, editors. The psychology of action. New York: The Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Allness D, Knoedler W. The PACT model: A Manual for PACT Start-Up. Arlington, VA: National Alliance for the Mentally Ill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SB. We Are Not Alone: Fountain House and the development of clubhouse culture. New York, NY: Fountain House, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- APA Taskforce, S. I. Statistical methods in psychology journals. American Psychologist. 1999;54(8):594–604. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E. The power of self-persuasion. American Psychologist. 1999;54(11):873–875. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E, Ellsworth P, Carlsmith JM, Gonzales MH. Methods of research in social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson E, Mills J. The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1959;59:177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Cohen G, Nail P. Self-affirmation theory: An update and appraisal. In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson WA, Greenfield TK. The UCSF Client Satisfaction Scales: I. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8. In: Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 3. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RC, Salzer MS. Accounting for unemployment among people with mental illness. Behavioral Science and Law. 2002;20(6):585–599. doi: 10.1002/bsl.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Tice DM. Role of self-presentation and choice in cognitive dissonance under forced compliance: Necessary or sufficient causes? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46(1):5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Beard JH. The rehabilitation services of Fountain House. In: Stein L, Test MA, editors. Alternatives to mental hospital treatment. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Beard JH, Propst RN, Malamud TJ. The Fountain House model of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1982;5(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Beavous J-L, Joule RV. A radical point of view on dissonance theory. In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Smith LM, Ciao AC. Peer-facilitated eating disorder prevention: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53(4):550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Jaccard J. Tests of multiplicative models in psychology: A case study using the unified theory of implicit attitudes, stereotypes, self-esteem, and self-concept. Psychological Review. 2006;113(1):155–169. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Vogler K, Resnick SG, Evans L, Drake R, Becker D. Dimensions of supported employment: Factor structure of the IPS fidelity scale. Journal of Mental Health (UK) 2001;10(4):383–393. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano R, Drake RE, Becker DR, Clark RE. Labor market conditions and employment of the mentally ill. Journal of Mental Health Policy Economics. 1999;2(2):51–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-176x(199906)2:2<51::aid-mhp44>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Rossi PH. Integrating theory into evaluation practice. In: Chen H, Rossi PH, editors. Using theory to improve program and policy evaluations. New York: Greenwood Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. Unwanted consequences and the self: In search of the motivation for cognitive dissonance. In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Salzer MS. The conflict between random assignment and treatment preference: Implications for internal validity. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2003;26:109–121. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembling BP, Chen DT, Vachon L. Life expectancy and causes of death in a population treated for serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(8):1036–1042. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Labor. (1998). Job Training Program Act, Disability Grant Program Funded Under Title III, Section 323, and Title IV, Part D, Section 452 (Vol. 63): Federal Register.

- Dickerson C, Thibodeau R, Aronson E, Miller DT. Using cognitive dissonance to encourage water conservation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1992;22:841–854. [Google Scholar]

- Dickey B, Normand SL, Weiss R, Drake R, Azeni H. Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(7):861–867. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.7.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L, Aronson E. The arousal and reduction of dissonance in social contexts. In: Cartwright D, Zander A, editors. Group dynamics. Evanston, IL: Row-Peterson; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L, Carlsmith JM. Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology. 1959;58:203–210. doi: 10.1037/h0041593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey JL. Long term support: The critical element to sustaining competitive employment: Where do we begin? Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1994;17(3):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer PM. The volitional benefits of planning. In: Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA, editors. The psychology of action. New York: The Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales MH, Aronson E, Costanzo M. Increasing the effectiveness of energy auditors: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18:1046–1066. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E. Toward an understanding of the motivation underlying dissonance effects: Is the production of aversive consequences necessary? In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E. Cognitive dissonance and experienced negative affect: Evidence that dissonance increases experienced negative affect even in the absence of aversive consequences. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26(12):1490–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E. The dissonance-inducing effects of an inconsistency between experienced empathy and knowledge of past failures to help: Support for the action-based model of dissonance. Basic & Applied Social Psychology. 2003;25(1):69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Brehm JW, Greenberg J, Simon L, Nelson DE. Evidence that the production of aversive consequences is not necessary to create cognitive dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Harmon-Jones C. Testing the action-based model of cognitive dissonance: The effect of action orientation on postdecisional attitudes. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28(6):711–723. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick TE, Bickman L, Rog DJ. Applied research design. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Heller RF, Patterson L. Establishing the evidence base for psychiatric services: Estimating the impact on the population. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(11):1558–1560. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.11.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendryx MS, Beigel A, Doucette A. Risk adjustment issues in mental health services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2001;28(3):225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF02287240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, Fisher WH, Hargreaves WA, Harding CM. Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55(11):1250–1257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.11.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CH, Spencer SJ, Zanna MP, Hoshino-Browne E, Correll J. Secure and defensive high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(5):969–978. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joule RV, Azdia T. Cognitive dissonance, double forced compliance, and commitment. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2003;33:565–571. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1991.9924671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller PA, Block LG. The effect of affect-based dissonance versus cognition-based dissonance on motivated reasoning and health-related persuasion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 1999;5(4):302–313. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Snibbe AC, Markus HR, Suzuki T. Is there any “free” choice? Self and dissonance in two cultures. Psychological Science. 2004;15(8):527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Kernan E, Postrado L. Toolkit for evaluating Quality of Life for persons with severe mental illness. Cambridge, MA: HSRI; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Leippe MR, Eisenstadt D. A self-accountability model of dissonance reduction: Multiple modes on a continuum of elaboration. In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: APA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin K. Constructs in psychology and psychological ecology. University of Iowa Studies in Child Welfare. 1944;20:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Barreira P, Hargreaves W, Bickman L, Fisher WH, Aronson E. Impact of referral source and study applicants’ preference for randomly assigned service on research enrollment, service engagement, and evaluative outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(4):781–787. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, DeCarlo L, Wang Q, Frey J, Barreira P. Work interest as a predictor of competitive employment: Policy implications for psychiatric rehabilitation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2001;28(4):279–297. doi: 10.1023/a:1011185513720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias C, Rodican CF, Hargreaves WA, Jones DR, Barreira PJ, Wang Q. Supported employment outcomes of a randomized controlled trial of assertive community treatment and clubhouse models. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(10):1406–1415. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.10.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinie MA, Fointiat V. Self-esteem, trivialization, and attitude change. Swiss Journal of Psychology. 2006;65(4):221–225. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ. Constructing social psychology: Creative and critical processes. Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Michel S, Fointiat V. Trivialisation versus rationalisation cognitive: Quand l’adhesion a la norme de consistance guide le choix du mode de redaction de la dissonance. Cahiers Internationaux de Psychologie Sociale. 2002;56:58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell K, Mazzeo S, Rausch S, Cooke K. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: Evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(2):120–128. doi: 10.1002/eat.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nail PR, Misak JE, Davis RM. Self-affirmation versus self-consistency: A comparison of two competing self-theories of dissonance phenomena. Personality & Individual Differences. 2004;36:1893–1905. [Google Scholar]

- Nel E, Helmreich R, Aronson E. Opinion change in the advocate as a function of the persuasibility of the audience: A clarification of the meaning of dissonance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1969;12:117–124. doi: 10.1037/h0027566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton MI, Cooper J, Monin B, Hogg MA. Vicarious dissonance: Attitude change from the inconsistency of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(1):47–62. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger DJ. The two paradigms of persistence. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 2002;128(3):237–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propst R. Standards for clubhouse programs: Why and how they were developed. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1992;16(2):25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Rindskopf D. Plausible rival hypotheses in measurement, design, and scientific theory. In: Bickman L, editor. Research design. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenheck R, Leslie DL, Keefe RSE, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Perkins DO, Stroup S, Hsiao JK, Lieberman J. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):411–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russert MG, Frey JL. The PACT Vocational Model: A step into the future. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1991;14(4):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. New York: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS for Windows. Chicago: SPSS; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stein LI, Test MA. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. I. Conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1980;37(4):392–397. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780170034003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Gau J, Shaw H. Testing mediators of intervention effects in randomized controlled trials: An evaluation of two eating disorder prevention programs. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(1):20–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J. What exactly have I done? The role of self-attribute accessibility in dissonance. In: Harmon-Jones E, Mills J, editors. Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stone J. Self-consistency for low self-esteem in dissonance processes: The role of self-standards. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29(7):846–858. doi: 10.1177/0146167203029007004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J, Cooper J. The effect of self-attribute relevance on how self-esteem moderates attitude change in dissonance processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2003;39:508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Suedfeld P, Epstein YM. Where is the ‘D’ in dissonance? Journal of Personality. 1971;39(2):178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Trach JS. Supported employment program characteristics. In: Rusch R, editor. Supported employment: Models, methods and issues. Sycamore, IL: Sycamore Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Uehara E, Srebnik D, Smukler M. Statistical and consensus-based strategies for grouping consumers in mental health level-of-care schemes. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2003;30(4):287–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1024080532651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]