Abstract

Although a bulk of literature shows that perceived social support (PSS) influences academic achievement, the mechanisms through which this effect operates received little empirical attention. The present study examined the multiple mediational effects of motivational beliefs (competence beliefs and subjective value) and emotions (anxiety and enjoyment) that may account for the empirical link between PSS (from parents, peers and teachers) and mathematics achievement. The participants of the study were 238 grade 7 students (average age = 13.2 years, girls = 54%, predominantly native Dutch middle class socioeconomic status). A bootstrap analysis (a relatively new technique for testing multiple mediation) revealed that the motivational beliefs and the emotions, jointly, partially mediated the effect of PSS on achievement. The proportion of the effects mediated, however, varied across the support sources from 55% to 75%. The findings lend support to the theoretical assumptions in the literature that supportive social relationships influence achievement through motivational and affective pathways.

Keywords: Social support, Motivational beliefs, Emotions, Multiple mediation, Math achievement

Introduction

How does perceived social support affect early adolescents’ academic achievement? A substantial body of literature shows that early adolescents’ perceived social support (PSS) is associated with their academic achievement. In general, studies show that early adolescents who perceive their parents, peers and/or teachers as supportive fare better in school than those who do not perceive their socializers as such (e.g., Goodenow 1993; Levitt et al. 1994; Wentzel 1998). Despite the growing body of evidence on the associations between the perception of supportive social relationships and academic achievement, the mechanisms through which social support exerts its influence on achievement have seldom been examined. A growing body of literature suggests that supportive social relationships may influence academic achievement indirectly through motivational and affective mechanisms (e.g., Dubow et al. 1991; Eccles 2007; Roeser et al. 2000; Wentzel 1998). Taken together, the emerging literature suggests that the presence of social support (or lack thereof) may precipitate positive or negative affective experiences (e.g., enjoyment, anxiety, anger) as well as adaptive or maladaptive self- and task related motivational beliefs (e.g., self-competence beliefs, subjective value), which in turn influence achievement. Although understanding such mechanisms of influence is important as it will inform further research and policy initiatives and may lead to the development of effective intervention programs to enhance early adolescents’ achievement, empirical evidence on the subject is lacking.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the motivational and affective pathways through which social support may influence the achievement of early adolescents. In particular, we examined how early adolescents’ competence beliefs in math and their subjective value of math as well as their level of math anxiety and math enjoyment mediate the association between perceived social support and math achievement. We chose early adolescence because it is a period characterized by confluence of biological, psychological, and social challenges (Lord et al. 1994). Particularly, it is described as a period of decline in academic motivation (e.g., interest, value, competence beliefs) and increased negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, anger) (e.g., Roeser et al. 1998, 2000). With respect to social support, it is a period when youth perceive their parents and teachers as less supportive whereas their perception of peer support peaks to the maximum (Furman and Buhrmester 1992). Thus, early adolescence is an ideal period to study the effect of PSS on achievement with particular emphasis on affective and motivational mechanisms, which happen to be in flux.

Social Support and Achievement

As alluded to earlier, previous studies have found relatively consistent evidence for the link between perceived social support and academic achievement. For instance, Rosenfeld et al. (2000) found that students with high support from peers, parents and teachers had better grades in a large, representative sample of middle and high school students than those without such support. A comparable study by Dubow et al. (1991) among students of lower middle class status of various ethnic groups showed similar findings. Their prospective study revealed that students’ report of aggregated social support (from family, peers and teachers) predicted their achievement 2 years later. This longitudinal study lends support to the importance of theoretically speculated causal associations between social support and achievement. Another study by Levitt et al. (1994) revealed similar findings. In a sample of multi-ethnic (African, European and Hispanic Americans) early adolescents of mixed socioeconomic status, the researchers found that the students’ perception of supportive relationships with parents, friends and teachers predicted their achievement as measured by average GPA in math, social sciences and English. Another important finding of this study is that when the level and effect of social support was examined, neither the level of support nor its effect on achievement differed by ethnicity. Lastly, Wentzel (1998) in a study of white middle class early adolescents found that students’ perception of support was correlated significantly with their cumulative GPA in math, English, science and social studies. The consistent findings across diverse samples suggest that social support is important for adolescents regardless of their socioeconomic status or ethnicity.

In spite of the extensive literature linking social support to achievement, little is known about the underlying mechanisms that can explain these relations. An overview of the growing body of literature on this aspect suggests that adolescents’ perceived social support may contribute to their achievement indirectly by way of motivational and affective outcomes. In particular, studies render compelling evidence on the associations between supportive social relationships and several motivational and emotional variables, which, in turn, are related to achievement. In what follows, we briefly discuss empirical evidence and theoretical explanations on social support and its association with motivational and emotional variables.

Social Support and Motivational Beliefs

Supportive social relationships have been linked to adaptive motivational beliefs including, but not limited to, goal orientations, academic values, academic efficacy and interest (e.g., Felner et al. 1985; Harter 1993; Wentzel 1998). Of particular interest to the current investigation are those studies that dealt with the associations between social support and competence beliefs as well as subjective values. Competence beliefs refer to students’ perceptions of how good they are at performing a given activity. Subjective values refer to students’ evaluations of the importance, interestingness and usefulness of a task (Wigfield and Eccles 2000). Research has documented noteworthy relations between students’ perceptions of social support (from parents, teachers and/or peers) and competence and value beliefs. Perceived parental support has been related positively to perceived competence and interest in school, a construct akin to value (e.g., Felner et al. 1985; Wentzel 1998). Similarly, perceived support from peers has been associated with intrinsic value and self-concept (Covington and Dray 2002; Harter 1993; Wentzel 1994). Finally, perceived support from teachers has been related to student reports of intrinsic values and self-concept (Covington and Dray 2002; Harter 1996; Midgley et al. 1989). In general, the studies support the assumption that familial, teacher, and peer relationships influence students’ motivational beliefs (e.g., Eccles 2007). Thus, the literature suggests that the simple perception that a social network is supportive can have the potential to boost ones self-confidence and to help internalize valued goals. There is also a relatively adequate amount of theoretical and empirical evidence that the perception of supportive relationships can influence students’ affective experiences.

Social Support and Emotions

Social psychological literature shows that the presence of supportive social relationships (or lack thereof) is associated with affective experiences. Individuals who have supportive social relationships experience more enjoyment and lesser anxiety than those who do not (Baumeister and Leary 1995). At a more general level, these authors argue that, whereas individuals who are provided with close supportive interpersonal relationships experience enjoyment, those who are deprived of such relationships tend to experience anxiety. Several motivation researchers (e.g., Roeser et al. 2000; Connell and Wellborn 1991) also argued that supportive and caring relationships within schools and homes in general would lead to the experience of positive emotions. In contrast, according to these authors, withdrawal of such relationships would lead to the experience of negative emotions.

Albeit limited, studies of the relationship between students’ PSS and emotions in academic settings support the theoretical assumptions. For instance, Wentzel (1998) reported significant negative correlations between social support (peer support, teacher support and family cohesion) and psychological distress (anxiety, depression, low self-esteem, and low wellbeing). Other studies that sought to determine the relations between perceived teacher support and affective outcomes of schooling found that teacher support correlates positively with enjoyment and negatively with anxiety (Fraser and Fisher 1982; Ma and Kishor 1997; Midgley et al. 1989). In addition, studies have found significant associations between a sense of acceptance (analogous to social support) and the enjoyment of learning (Battistich et al. 1995). Thus, the findings suggest that perceived social support covaries with emotions.

Motivational Beliefs, Emotions and Achievement

Insight into the relationship between achievement and motivational beliefs as well as emotions is fairly well established. A great deal of research has documented substantial associations between competence and value beliefs on the one hand and academic achievement on the other (e.g., Pintrich and De Groot 1990 see Wigfield et al. 2006 for a review). In general, the studies suggest that those students who perceive themselves to be competent and who value what they learn at school tend to perform better than those who lack such beliefs.

The links between anxiety or enjoyment and achievement are evident in a number of studies and appear to be well documented as well. In general, whereas achievement is negatively correlated with anxiety (e.g., Pintrich and De Groot 1990), it is positively correlated with enjoyment (e.g., Pekrun et al. 2002). In addition to such domain-general findings, research in mathematics education also shows similar patterns. For instance, two meta-analytic studies (Hembree 1990; Ma 1999) found a significant negative association between mathematics anxiety and mathematics achievement. Math enjoyment has often been embedded in measures that assess students’ attitude towards math. In such studies, enjoyment has been related substantially to achievement in math (e.g., Ma 1997). In general, existing research suggests that both anxiety and enjoyment influence math achievement.

The Present Study

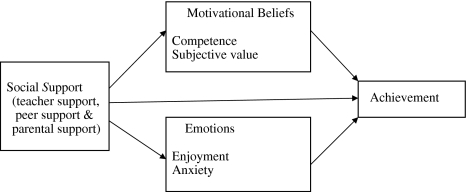

As noted above, the mechanisms by which PSS influences achievement have engendered little empirical work. Based on the literature reviewed in the preceding sections, we proposed that the effect of PSS on achievement is transferred through students’ “inner psychological resources” such as competence beliefs, subjective values, as well as enjoyment and anxiety. Heeding researchers’ call for domain specificity in measurement of social support (Lakey and Cohen 2000), motivational beliefs, (Pajares 1996) and emotions (Goetz et al. 2006), we defined and assessed all the variables in the current study with regard to mathematics, a school domain in which declines in early adolescents’ academic functioning are particularly visible (Roeser and Eccles 1998). In short, we tested whether competence beliefs, subjective value, anxiety and enjoyment jointly mediate the effects of perceived support (from parents, peers and teacher separately) on mathematics achievement. Additionally, we sought to determine the extent to which a specific intervening variable mediates the effect of PSS on achievement after controlling for the remaining mediators. We also examined the direct effects of support from the three sources. The hypothesized multiple mediation model is presented in Fig. 1. Although the figure suggests a causal relationship between the variables, we acknowledge that reciprocal relationships could also be possible. Nevertheless, most of the associations are derived from existing empirical evidence as well as theoretical models that portray the relationships between the variables as depicted in the figure. Our use of multiple mediators is justified by the understanding that a single mechanism is not apt to explain the complex associations between social support and achievement.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of the study

Based on the existing literature, we hypothesized that (1) competence beliefs, subjective value, anxiety and enjoyment would jointly mediate the relationship between PSS (parents, peers and teacher each separately) and achievement; and (2) each of the mediators (competence beliefs, subjective value, anxiety and enjoyment) would uniquely mediate the relationship between PSS (parents, peers and teacher each separately) and achievement.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The participants were 238 seventh-grade students (54% girls) from 10 classes in a junior secondary school in a suburban predominantly middle class community (Statistics Netherlands 2004). Almost all participants were native Dutch. The mean age of the participants was 13.2 (SD = 0.5) years. After we received informed parental consent, we distributed a set of questionnaires in the students’ regular classrooms in April 2007. The students were able to complete the questionnaires in 15–20 min.

Perceived Social Support Measures

The perceived social support measures asked the participants how often their parents, peers and math teacher demonstrated supportive behaviors such as caring, valuing, esteeming and being helpful in the context of learning math. For each potential source of support, we adapted a five-item measure from three existing instruments: Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale (Malecki and Demaray 2002), What is Happening In This Classroom (Fraser et al. 1996) and Classroom Life Measure (Johnson et al. 1983). The students responded to the measures on a five-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (almost always).

Perceived Parental Support

This variable was measured using five items that taped the students’ perceptions of their parents’ caring, encouragement and helpfulness. Example items include: “My parents care about my performance in math”; “My parents encourage me to do well in math”. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.70 in the present sample.

Perceived Peer Support

This construct was measured using five items that assessed the students’ perception of their peers’ caring, valuing and helpfulness. Sample items for this measure are: “My friends care about how much I learn in math”, “My classmates spend time doing math with me”. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the measure was 0.66 in the current study.

Perceived Teacher Support

This variable was measured using five items that assessed the students’ perception of their math teacher’s caring, friendliness and helpfulness. Example items are: “The teacher considers my feelings”; “The teacher helps me when I have trouble with some math problem”. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability of this measure was .74.

Motivational Beliefs Measures

Measures of the motivational beliefs included youth’s competence beliefs and their subjective value beliefs in math. The measures were adapted from Wigfield and Eccles (2000). Both measures were rated on a 5-point Likert type scale, ranging from 1 to 5.

Competence Beliefs

Competence beliefs measure (5 items) assessed among others how good the participants thought they were at math, how well they expected to do in the future in math, and how good they thought they would be at learning something new in math. An example item is “How good at math are you?” (1 = not at all good, 5 = very good). The Cronbach’s alpha reliability in the current sample was 0.81.

Subjective Value

Subjective value measure asked the participants how interesting math was, how important they thought being good at math, and how useful they thought math was. Wigfield and Eccles (2000) argue that subjective value comprises at least intrinsic value (interestingness of a task), attainment value (importance of doing well on a task for confirming ones self-schema) and utility value (usefulness of a task for an individual’s future goals). Yet, recent works of Eccles and colleagues (e.g., Durik et al. 2006) use two components; namely, interest (intrinsic value) and importance (a composite of attainment value and utility value). In the current study, we subjected the items measuring subjective value beliefs to a component factor analysis. The analysis yielded a two-factor solution explaining about 72.8% of the variance. Following Durik et al. (2006), the factors were labeled interest (2 items) (e.g., “How much do you like doing math?”[1 = not at all, 5 = very much]), and importance (3 items) (e.g., “How important is being good in math for you?” [1 = not at all important, 5 = very important]). The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were 0.83 and 0.72 for interest and importance, respectively, in the present sample.

Emotions Measures

Two scales assessed the students’ level of math enjoyment and math anxiety. The scales were adapted from the Academic Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics (AEQ-M, Pekrun et al. 2005). Both math enjoyment and math anxiety scales were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Math Enjoyment

The students’ enjoyment of mathematics was assessed using math enjoyment scale (7 items). Sample items assessing math enjoyment include: “I enjoy studying math”; “I enjoy the challenge of taking math tests”. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.75 for the present sample.

Math Anxiety

Participants’ anxiety towards math was measured using math anxiety scale (8 items). Examples of items assessing math anxiety are: “I get tense and nervous while studying math”, “I am anxious about taking more math courses”. In the current sample, the internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.81.

Achievement

Mathematics Achievement

We collected the participants’ average math grade (of three trimesters) for the academic year in June 2007 from the school record office. The Dutch grading scale ranges from 1 (poor) to 10 (outstanding). Grades of 5.5 and above are passing grades.

Results

The intercorrelations among the study variables are displayed in Table 1. The three social support variables correlated significantly with math achievement. Both parental and teacher support were significantly related to the three motivational beliefs and the two discrete emotions. Peer support was significantly related to competence, interest and enjoyment but not to importance and anxiety. Math achievement was positively associated with competence, interest, importance and enjoyment but was negatively correlated with anxiety. Finally, gender (boys = 1, girls = 0) was negatively correlated with peer support and math achievement. Since we felt that the associations between gender and math achievement might bias the findings, we controlled for gender in the subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Summary statistics and bivariate correlations among the study variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental support | .43** | .34** | .23** | .20** | .27** | .19** | −.15* | .34** | −.09 | |

| 2. Peer support | .34** | .12* | .14* | .08 | .19** | −.07 | .25** | −.44** | ||

| 3. Teacher support | .26** | .28** | .13** | .45** | −.21** | .43** | −.13 | |||

| 4. Competence | .48** | .33** | .45** | −.60** | .62** | .09 | ||||

| 5. Interest | .42** | .27** | −.21** | .40** | .09 | |||||

| 6. Importance | .19** | −.11 | .25** | −.07 | ||||||

| 7. Enjoyment | −.33** | .50** | .04 | |||||||

| 8. Anxiety | −.46** | −.05 | ||||||||

| 9. Achievement | −.16* | |||||||||

| 10. Gender | ||||||||||

| Mean | 3.42 | 3.21 | 3.61 | 3.66 | 3.77 | 3.06 | 2.31 | 1.86 | 7.55 | – |

| Std. Dev. | .63 | .89 | .75 | .69 | .73 | .83 | .60 | .64 | .94 | – |

* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01

To test the multiple mediation hypotheses, we used a bootstrapping approach (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Shrout and Bolger 2002). Bootstrapping (resampling) strategy was used because it is suitable for testing multiple mediators simultaneously. The procedure uses original sample data as a population reservoir and takes random samples of size “n” with replacement and estimates the total and specific indirect effects. Testing the total indirect effect is similar to testing the overall effect of multiple independent predictors in a regression analysis (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Significant total indirect effect suggests that as a set, the multiple mediators (M’s) transmit the effect of an independent variable (X) on a dependent variable (Y). A specific indirect effect refers to the extent to which a mediator transmits the effect of X on Y, above and beyond the other mediators. Preacher and Hayes (2008) recommend bootstrapping over the causal step strategy proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), because (a) it relatively provides more accurate type I error rates and (b) it has greater power in detecting indirect effects.

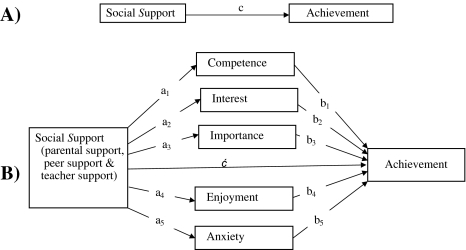

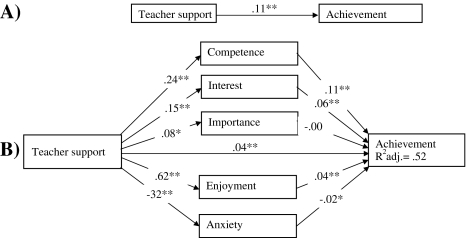

The analytic diagram (see Fig. 2) shows the coefficients estimated. The “a” coefficients represent the effects of social support on the mediators, the “b” coefficients represent the effects of the mediators on achievement partialling out the effect of social support. The “c” in panel A of the figure is the total effect of social support on achievement. The “ć”in panel B is the direct effect of social support on achievement. The specific indirect effects are represented by a 1 b 1 (competence), a 2 b 2 (interest), a 3 b 3 (importance), a 4 b 4 (anxiety), and a 5 b 5 (enjoyment). The total indirect effect is the sum of all the specific indirect effects. To test the hypotheses, we utilized the SPSS macros for multiple mediation (Preacher and Hayes 2008). The macros give estimates of the specific indirect effects as well as of the total indirect effect. Current analyses utilized 1000 bootstrap samples to create pseudo population of indirect effects. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) were used to evaluate the significance and the magnitude of indirect effects estimated through the bootstrap technique. An effect is significant if the confidence interval does not include zero. We described the extent of mediation by calculating the proportion mediated (i.e., ratio of indirect effect to total effect, Shrout and Bolger 2002).

Fig. 2.

Analytic diagram for the multiple mediation model proposed

As a preliminary step for testing the multiple mediation, the paths a, b, c and ć shown in Fig. 2 were determined controlling for sex of the participants for the three support sources separately. The total effect of perceived social support (i.e., without the inclusion of the mediators) on achievement was tested individually for each support source. The direct effects of perceived social support on the mediators as well as the direct effects of the mediators on achievement were tested for each of the support sources separately.

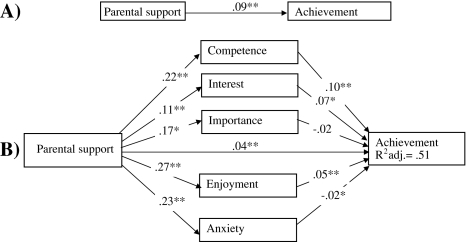

The results showed that perceived parental support had a direct positive effect on competence, interest, importance and enjoyment but a direct negative effect on math anxiety. In the test of the direct effects of the mediators on achievement, in the parental support model, competence, interest, anxiety and enjoyment significantly predicted achievement. Nevertheless, importance did not have a statistically significant independent contribution to the model in the presence of the other mediators. Consequently, importance was not used in the subsequent analyses. The total effect of parental support on achievement was significant and so was its direct effect. Overall, the parent model explained 51% of the variance in mathematics achievement (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Parental support, mediators and achievement (** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05)

Examination of the total and specific indirect effects of perceived parental support on achievement revealed interesting findings. The total indirect effect was significant with the 95% bootstrap confidence interval excluding zero (CI.95 = .027, .070) (see row labeled total in Table 2). This suggests that the effect of perceived parental support on achievement was multiply mediated by the motivational and emotional variables in general. Examination of the proportion of effects mediated shows that 55% of the total effect of parental support on achievement is mediated by the motivational beliefs and emotion variables altogether. Inspection of the specific indirect effects revealed that competence, interest, math anxiety, and math enjoyment significantly uniquely mediated the associations between parental support and achievement (see 95% CIs in Table 2).

Table 2.

Total and specific mediated effects and their corresponding bootstrap confidence intervals for parental support, peer support, and teacher support

| Indirect effects | Parental support | Peer support | Teacher support | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | 95% CIs | Estimate | SE | 95% CIs | Estimate | SE | 95% CIs | |

| Competence | .023 | .007 | (.011, .040) | .020 | .008 | (.005, .040) | .027 | .008 | (.014, .048) |

| Interest | .008 | .004 | (.001, .020) | .004 | .002 | (.000, .014)* | .009 | .005 | (−.000, .022)* |

| Enjoyment | .013 | .005 | (.004, .025) | .015 | .005 | (.006, .027) | .023 | .008 | (.008, .041) |

| Anxiety | .006 | .003 | (.001, .017) | – | – | – | .007 | .003 | (.000, .020)* |

| Total | .048 | .011 | (.027, .070) | .039 | .010 | (.018, .065) | .066 | .013 | (.043, .098) |

* The lower CIs are not exactly zero. The next lowest number after 0.000 is 3

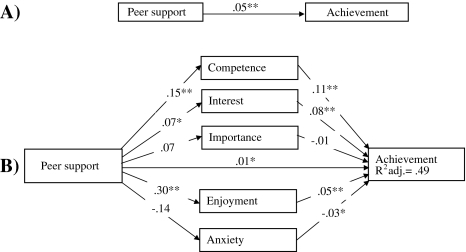

With regard to the direct effects of peer support on the mediators, the results were somewhat similar to those found in the parental support model (see Fig. 4). Peer support had significant positive effects on competence, interest and math enjoyment. However, it had no significant effects on importance and anxiety. With the exception of importance, the proposed mediators significantly predicted achievement. The total effect and direct effect of peer support on achievement were found to be significant. Overall, about 49% of the variance was explained by the variables included in the equation (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Peer support, mediators and achievement (** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05)

The total indirect effect of perceived peer support on achievement was also significant (CI.95 = .018, .065), but relatively smaller in magnitude compared with that found in the parent model (see Table 2). The analysis of the ratio of the total indirect effect on the total effect of peer support showed that almost 75% of the effect is mediated. The results for specific indirect effects of the proposed mediators showed that math enjoyment, interest and competence significantly mediated the associations between peer support and achievement (see 95% CIs in Table 2).

Teacher support had direct positive effects on competence, interest, importance and math enjoyment but a direct negative effect on math anxiety. In the test of the direct effects of the mediators on achievement, importance did not have a significant effect. Competence, interest, and math enjoyment had positive direct effects on achievement. As in the other models, math anxiety had a negative effect on achievement. The total effect and direct effect of teacher support on achievement were significant. Overall, about 51% of the variance in achievement was explained by teacher support and the mediating variables (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Teacher support, mediators and achievement (** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05)

The specific and total indirect effects of teacher support are presented in Table 2. The total indirect effect of teacher support on achievement was significant (CI.95 = .043, .098). The motivational beliefs and the emotions jointly mediated the effect of perceived teacher support on achievement. The results show that about 62% of the total effect of teacher support on achievement is mediated by the motivational beliefs and the emotions in total. As is the case with the effects of parental support, the indirect effects of competence, math anxiety and math enjoyment were all significant (see Table 2). Surprisingly, interest did not uniquely contribute to the indirect effect.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine the mediational roles of motivational beliefs and emotions in the association between perceived social support (PSS) and mathematics achievement of early adolescents. Generally, the results revealed that the motivational and emotional variables multiply mediate the effect of PSS on achievement. In other words, PSS influenced achievement through its effects on competence, interest, enjoyment and anxiety, reinforcing the multiple mediation model proposed. Nevertheless, not all the proposed intervening variables uniquely mediated the association between PSS and achievement in the three models tested. In addition, the magnitude of the mediated effects of social support as well as the unique effects of the mediators varied across the support sources. In general, the analyses provide support for the mediational assumptions in the literature.

The results revealed that the students’ perceived support (from parents, peers and teacher) facilitated their motivational beliefs and emotions, which, in turn, enhanced their achievement. First, the findings show that students who describe their parents as supportive appeared to possess adaptive motivational and emotional qualities. Such students in general feel less anxious about math, enjoy math, feel confident in math and tend to be interested in math, which in turn influence their performance. The results affirm the motivational and affective significance of parental support in early adolescents’ academic adjustment (Roeser et al. 2000). Moreover, the results demonstrated that each of the four mediators uniquely accounted for significant proportions of the variance in the overall mediated effect of parental support. The mediational effects of competence beliefs and interest found in this study support the theoretical discussions on the effect of parental socialization of perceived competence in and values of mathematics (Parsons et al. 1982). The unique contribution of interest to the overall mediated effect is consistent with that of Wentzel (1998) who found that parental support indirectly influenced early adolescents’ achievement through its effect on school and class related interest. Finally, the findings on the mediational roles of anxiety and enjoyment are consistent with the notion that supportive relationships with significant others reduces anxiety and enhances enjoyment which in turn are associated with adaptive outcomes (Baumeister and Leary 1995). In general, the mediational roles of the motivational beliefs and the emotions in the current study attest to the importance of parental support in early adolescents’ academic adjustment to school.

Second, the results revealed that the association between perceived peer support and achievement was jointly mediated by competence, interest and enjoyment. The results suggest that supportive peer relationships affect adolescents’ achievement by way of developing motivational and emotional functioning. Indeed, the three mediators (competence, interest and enjoyment) had significant unique contributions to the overall mediated effect. The results concerning the unique effects of the mediators corroborate with previous findings that examined the link between aspects of peer relationships and motivational and affective outcomes (e.g., Battistich et al. 1995; Wentzel 1994). In general, the findings support Harter’s (1996) theoretical explanations that peer support influences students’ motivational beliefs and affective experiences, which in turn affect their adjustment.

Finally, the results indicate that students who perceived their teacher as supportive tend to show adaptive motivational and affective patterns of behavior, which, in turn, are related to achievement. Four variables (competence, interest, enjoyment and anxiety) mediated the association between perceived teacher support and achievement. The perception that the mathematics teacher is supportive may have an influence on how students reflect on their self-system in that domain, which in turn affects their achievement. Students’ perceived teacher support implies that there is an authoritative resource they can access in times of stress relating to school mathematics. This provides them with a sense of being secure in the classroom, which in turn, boosts their competence beliefs. One previous study (Levitt et al. 1994) on the mediational role of competence beliefs in the social support and achievement link augments the current finding. Previous empirical work has found the importance of teacher support in maintaining and sustaining students’ intrinsic value (e.g., Midgley et al. 1989). As regards the emotional variables, both anxiety and enjoyment uniquely mediated the effect of teacher support on achievement. The results are consistent with previous findings that reported that the perception of teacher support reduces feelings of anxiety and insecurity (Trickett and Moos 1974) and enhances feelings of enjoyment (Fraser and Fisher 1982) and that anxiety and enjoyment significantly predict achievement (e.g., Hembree 1990; Ma 1997).

In addition to the mediation effects, we examined the direct effect of PSS on achievement. Generally, early adolescents who reported higher social support (from parents, peers and teacher) scored higher on mathematics achievement. The finding supports the contention that supportive social relationships directly influence children and adolescents’ adjustment (Compas 1987). Supportive social relationships with significant others may provide early adolescents with knowledge and skills with which they can face the challenges of schoolwork. Teacher, peer and parental advice and help on how to deal with academic tasks can enhance students’ achievement directly. In addition, early adolescents’ interaction with the support sources during stressful encounters may buffer the effects of stress and hence promote performance. The finding is consistent with previous studies that showed the effect of perceived supportive social relationships on early adolescents’ academic achievement (e.g., Goodenow 1993; Wentzel 1998).

The results showed that the motivational beliefs and the specific emotions included in the analyses partially accounted for the effects of PSS on achievement. Among the proposed intervening variables, importance did not contribute significantly to prediction of math achievement in all the three models tested. Consequently, it was not used in subsequent analyses. The results suggest that once the other mediators are controlled, the predicting power of importance diminishes. Given recent evidence that task values determine intentions and choices more strongly than performance (see Wigfield and Eccles 2000), the finding is not surprising. Nevertheless, the significance of interest (intrinsic value), a component of task value, demonstrated in this study suggests that more detailed analysis is needed to disentangle the relative effects of task value components. In general, however, the findings of the current study support the general assumptions in the literature that supportive social relationships promote adjustment—directly or indirectly through sustaining and maintaining competence and value beliefs as well as affective experiences (e.g., Harter 1996; Roeser et al. 2000).

However, interpretation of the current findings should be made with several limitations in mind. First, our cross-sectional design involved concurrent data on social support, the mediators and achievement. This makes it difficult to draw definitive causal conclusions. Nevertheless, the evidence for the associations certainly accord with previous studies that employed longitudinal designs (e.g., Dubow et al. 1991) as well as theoretical models on the associations between supportive social relationships and academic adjustment (e.g., Eccles 2007). Future research may benefit from a longitudinal mediational design whereby social support is measured before the mediators after which achievement is measured. Second, our measure of social support was crude. Literature on social support suggests that different support functions (e.g., emotional, informational and instrumental) may relate differentially to various adjustment indices (e.g., depression, academic achievement). Specifying and assessing these functions in future research may help in painting a more nuanced picture of the linkage between social support and achievement. Finally, some characteristics of socializing agents (e.g., parental and teacher expectations, friends’ achievement motivation) may influence each of the variables in this study. Controlling such variables may help one to disentangle the intricate relations between social support, motivational beliefs, emotions and achievement more precisely.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the current study have important implications. Our analyses suggest that early adolescents, who perceived their parents, peers and teacher as supportive, are faring well in school with regard to their motivation, emotion and achievement in math. It would be worthwhile to set up peer support schemes whereby older adolescents help the younger ones particularly during critical transition years (e.g., Grades 7 or 9). Such transitions are usually associated with the demise of prior peer networks. It would also be useful to strengthen close contact between teachers and their students. Additionally, schools may inform parents of the benefits of their praise and encouragement in their children’s achievement. In general, the findings of the current study suggest that schools should pay particular attention to social context of adolescents’ learning. Schools should focus on creating supportive social relationships and should encourage parents to provide supports needed at home to their children.

This study makes two important contributions to the literature on the linkage between social support and achievement among early adolescents. First, we consider how motivational beliefs and emotions jointly mediate the association between social support and achievement. We find that social support influences achievement through the adolescents’ beliefs and affective experiences. Previous studies have rarely focused on studying the mechanisms underlying the effects of social support on achievement (see Wentzel 1998). Second, we examine the role of a specific mediator in relation to others in the same model. Results from such analyses inform both theory and practice. Theoretically, they provide information on the relative importance of a mediator, which further improves theorizing the mechanisms of influence. Practically, the results suggest that interventions may aim at only the limited promising intervening variables for an optimal outcome. In conclusion, assessing the mechanisms through which social support influences early adolescents’ achievement is important because multitudes of variables may intervene in the process which if not detected would lead to erroneous conclusions regarding direct effects.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Biographies

Wondimu Ahmed

is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. He received his M.Sc. degree in Education from the same university in 2005. His research interests include achievement motivation, academic emotions, self-regulated learning; social relationships and academic adjustment of early adolescents.

Alexander Minnaert

is professor of Special Needs and Clinical Education at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. He received his Ph.D. in Instructional Psychology from the University of Leuven, Belgium. His research interests are focused upon motivation, emotion, self-regulation and learning (disabilities).

Greetje van der Werf

is professor of Educational Sciences at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. She received her Ph.D. in Behavioral and Social Sciences from the University of Groningen. Her research interests include individual and group related differences in students’ long-term educational attainment, based on theory and research on learning and instruction.

Hans Kuyper

is a Senior Researcher at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. He received his Ph.D. in Behavioral and Social Sciences from the University of Groningen. He is interested in social comparison, personality and achievement motivation and their influence on long-term educational attainment.

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistich V, Solomon D, Kim D, Watson M, Schaps E. Schools as communities, poverty levels of student populations, and students' attitudes, motives, and performance: A multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal. 1995;32:627–758. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:393–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Gunnar MR, Sroufe LA, editors. Self processes and development. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1991. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Covington MV, Dray E. The developmental course of achievement motivation: A need-based approach. In: Wigfield A, Eccles JS, editors. Development of achievement motivation. San Diego, CA, US: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Tisak J, Causey D, Hryshko A. A two-year longitudinal study of stressful life events, social support, and social problem-solving skills: Contributions to children’s behavioral and academic adjustment. Child Development. 1991;62:583–599. doi: 10.2307/1131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durik AM, Vida M, Eccles JS. Task values and ability beliefs as predictors of high school literacy choices: A developmental analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:382–393. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.2.382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS. Families, schools, and developing achievement-related motivations and engagement. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of socialization. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 665–691. [Google Scholar]

- Felner RD, Aber MS, Primavera J, Cauce AM. Adaptation and vulnerability in high-risk adolescents: An examination of environmental mediators. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13:365–379. doi: 10.1007/BF00911214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser BJ, Fisher DL. Predicting students’ outcomes from their perceptions of classroom psychosocial environment. American Educational Research Journal. 1982;19:498–518. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, B. J., McRobbie, C. J., & Fisher, D. L. (1996, April). Development, validation and use of personal and class forms of a new classroom environment instrument. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York.

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.2307/1130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz T, Frenzel AC, Pekrun R, Hall NC. The domain specificity of academic emotional experiences. Journal of Experimental Education. 2006;75:5–29. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.75.1.5-29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Relationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:21–43. doi: 10.1177/0272431693013001002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Visions of self: Beyond the me in the mirror. In: Jacobs JE, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation. Lincoln, NE, US: University of Nebraska Press; 1993. pp. 99–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Teacher and classmate influences on scholastic motivation, self-esteem and level of voice in adolescents. In: Juvonen J, Wentzel KR, editors. Social motivation: Understanding children’s school adjustment. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 11–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hembree R. The nature, effects, and relief of mathematics anxiety. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 1990;21:33–46. doi: 10.2307/749455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson R, Anderson D. Social interdependence and classroom climate. The Journal of Psychology. 1983;114:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Cohen S. Social support theory and measurement. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt MJ, Guacci-Franco N, Levitt JL. Social support and achievement in childhood and early adolescence: A multicultural study. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1994;15:207–222. doi: 10.1016/0193-3973(94)90013-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lord SE, Eccles JS, McCarthy KA. Surviving the junior high school transition: Family processes and self-perceptions as protective and risk factors. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:162–199. doi: 10.1177/027243169401400205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. Reciprocal relationships between attitude toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics. The Journal of Educational Research. 1997;90:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ma X. A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety towards mathematics and achievement. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 1999;30:520–540. doi: 10.2307/749772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Kishor N. Attitude towards self, social factors, and achievement in mathematics: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review. 1997;9:89–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1024785812050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki CK, Demaray MK. Measuring perceived social support: Development of the child and adolescent social support scale (CASSS) Psychology in the Schools. 2002;39:1–18. doi: 10.1002/pits.10004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Midgley C, Feldlaufer H, Eccles JS. Student/teacher relations and attitudes toward mathematics before and after the transition to junior high school. Child Development. 1989;60:981–992. doi: 10.2307/1131038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares F. Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Review of Educational Research. 1996;66:543–578. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JE, Adler TF, Kaczala CM. Socialization of achievement attitudes and beliefs: Parental influences. Child Development. 1982;53:310–321. doi: 10.2307/1128973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Frenzel, A. C. (2005). Academic Emotions Questionnaire-Mathematics (AEQ-M). User’s manual. Department of Psychology, University of Munich.

- Pekrun R, Goetz T, Titz W, Perry RP. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist. 2002;37:91–106. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich PR, De Groot EV. Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1990;82:33–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.82.1.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS. Adolescents’ perceptions of middle school: Relation to longitudinal changes in academic and psychological adjustment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1998;8:123–158. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0801_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Sameroff AJ. Academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence: Longitudinal relations, patterns, and prediction by experience in middle school. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:321–352. doi: 10.1017/S0954579498001631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeser RW, Eccles JS, Sameroff AJ. School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal. 2000;100:443–471. doi: 10.1086/499650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld LB, Richman JM, Bowen GL. Social support networks and school outcomes: The centrality of the teacher. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2000;17:205–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1007535930286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Netherlands. (2004). Income and spending. Retrieved September 6, 2008, from http://www.cbs.nl/nl-NL/menu/themas/inkomenbestedingen/cijfers/default.htm.

- Trickett EJ, Moos RH. Personal correlates of contrasting environments: Student satisfactions in high school classrooms. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1974;2:1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00894149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Relations of social goal pursuit to social acceptance, classroom behavior, and perceived social support. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1994;86:173–182. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.86.2.173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1998;90:202–209. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield A, Eccles JS. Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 2000;25:68–81. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation. In W. Damon (Series Ed.) & N. Eisenberg (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 933–1002). New York: Wiley.