Abstract

The risk of late-onset cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection remains a concern in seronegative kidney and/or pancreas transplant recipients of seropositive organs despite the use of antiviral prophylaxis. The optimal duration of prophylaxis is unknown. We studied the cost effectiveness of 6- versus 3-mo prophylaxis with valganciclovir. A total of 222 seronegative recipients of seropositive kidney and/or pancreas transplants received valganciclovir prophylaxis for either 3 or 6 mo during two consecutive time periods. We assessed the incidence of CMV infection and disease 12 mo after completion of prophylaxis and performed cost-effectiveness analyses. The overall incidence of CMV infection and disease was 26.7% and 24.4% in the 3-mo group and 20.9% and 12.1% in the 6-mo group, respectively. Six-month prophylaxis was associated with a statistically significant reduction in risk for CMV disease (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.72), but not infection (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.37 to 1.14). Cost-effectiveness analyses showed that 6-mo prophylaxis combined with a one-time viremia determination at the end of the prophylaxis period incurred an incremental cost of $34,362 and $16,215 per case of infection and disease avoided, respectively, and $8,304 per one quality adjusted life-year gained. Sensitivity analyses supported the cost effectiveness of 6-mo prophylaxis over a wide range of valganciclovir and hospital costs, as well as variation in the incidence of CMV disease. In summary, 6-mo prophylaxis with valganciclovir combined with a one-time determination of viremia is cost effective in reducing CMV infection and disease in seronegative recipients of seropositive kidney and/or pancreas transplants.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection remains one of most common opportunistic infections in solid organ transplant patients despite availability of specific and efficacious anti-viral drugs.1,2 Solid organ transplant patients who have a negative CMV serology and receive an organ from a positive CMV serologic donor (D+/R−) have the highest incidence of CMV disease with and without prophylaxis.2–5 Although the risk for CMV disease persists for life, the majority of cases occur shortly after completion of prophylaxis, often within the first year after transplant.6 CMV disease causes significant morbidity, increases mortality, and is associated with inferior transplant outcomes, particularly in the case of kidney transplantation.7–10 Furthermore, the presence of CMV disease is one of the most frequent infectious causes of hospitalization early after transplantation, increasing the total cost of kidney transplantation and reducing its overall effectiveness.7,11–13

Valganciclovir (VGCV) is an effective anti-CMV agent for prophylaxis and treatment of CMV disease that is widely used in transplantation.2,14–16 Although the recommended dose for CMV prophylaxis is 900 mg daily adjusted for renal function, a recent study showed that VGCV at 450 mg daily provides similar drug exposure compared with oral ganciclovir (GCV) at 1000 mg three times daily in kidney transplant patients, a dose similarly effective for CMV prophylaxis.2,17 In most studies, VGCV prophylaxis consisted of 100 d after transplant, after which time the risk of CMV infection and disease increased.2,18,19 Extending the duration of VGCV prophylaxis beyond the early post-transplant period may abrogate this transient increase in the risk of infection and disease.20,21 In this regard, the optimal duration of prophylaxis for CMV D+/R− patients has not been determined and is the subject of ongoing study.22 Cost, efficacy, and safety are important factors in determining the optimal duration of VGCV prophylaxis. Over the past two decades, various strategies have been used including pre-emptive versus universal prophylaxis and shorter versus longer period of prophylaxis.20,21,23,24 Although several clinical studies comparing universal prophylaxis versus pre-emptive anti-viral therapy have found similar efficacy and cost in managing CMV infection across various combinations of donor and recipient CMV serologic status, two meta-analyses did find that the use of universal prophylaxis was associated with reduced risk for CMV disease and death.23–26

This study is based on a single center experience comparing two CMV prophylaxis strategies. We report here the clinical outcome and cost-effectiveness analyses of 6- versus 3-mo VGCV prophylaxis in CMV D+/R− de novo kidney and/or pancreas transplant patients.

Results

Patients

Between March 2002 and March 2007, a total of 222 CMV D+/R− kidney and/or pancreas transplant recipients were included in this study. One hundred thirty-one patients received VGCV for 3 mo (3-mo group), whereas 91 patients received 6 mo of therapy (6-mo group). Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups are presented in Table 1. Patients from both groups were comparable with respect to age, gender, race, calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) used, baseline renal function, and incidence of acute rejection. However, the 6-mo group had more deceased and expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidney transplants, more frequent use of induction agents, particularly rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, higher use of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and more cases of repeat transplant and delayed graft function. Among all patients receiving MMF, the daily dose was similar between the groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| 3-Mo (n = 131) | 6-Mo (n = 91) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years; mean ± SD) | 44.5 ± 11.8 | 45.8 ± 12.3 | 0.42 |

| Gender (%) | 0.54 | ||

| Male | 84 (64.1) | 62 (68.1) | |

| Female | 47 (35.9) | 29 (31.9) | |

| Race (%) | 0.38 | ||

| African American | 23 (17.6) | 12 (13.2) | |

| Others | 108 (82.4) | 79 (86.8) | |

| Renal diagnosis | 0.21 | ||

| DM | 50 | 32 | |

| PCKD | 18 | 5 | |

| HTN | 9 | 10 | |

| GN | 31 | 22 | |

| Others | 23 | 22 | |

| Living donor (%) | 70 (53.4) | 31 (34.1) | 0.004 |

| First transplant (%) | 124 (94.7) | 80 (87.9) | 0.07 |

| HCV positive (%) | 2 (1.6) | 4 (4.4) | 0.22 |

| Delayed graft function (%) | 8 (6.1) | 12 (13.2) | 0.07 |

| Donor age (years, mean ± SD) | 40.1 ± 14.2 | 38.5 ± 15.4 | 0.45 |

| Donor gender (M %) | 50 (38.2) | 43 (47.3) | <0.001 |

| Expanded criteria donor (ECD) (%) | 12 (9.5) | 20 (22.0) | 0.01 |

| CNI use (%) | 0.36 | ||

| CsA | 110 (84.0) | 72 (79.1) | |

| Tac | 21 (16.0) | 19 (20.9) | |

| Anti-proliferative (%) | 0.02 | ||

| MMF | 113 (86.5) | 87 (95.6) | |

| Others | 18 (13.5) | 4 (4.4) | |

| MMF dose (mg/d, mean ± SD) | 2092.9 ± 331.1 | 2069.0 ± 333.9 | 0.61 |

| Maintenance regimens (%) | 0.05 | ||

| CsA/MMF | 94 (71.8) | 68 (74.7) | |

| Tac/MMF | 19 (14.5) | 19 (20.9) | |

| Others | 18 (13.7) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Induction (%) | 0.02 | ||

| None | 60 (45.8) | 28 (30.8) | |

| Thymoglobulin | 47 (35.9) | 50 (54.9) | |

| Basiliximab | 24 (18.3) | 13 (14.3) | |

| MDRD at baseline (ml/min, mean ± SD) | 67.7 ± 19.9 | 66.1 ± 21.4 | 0.57 |

| Acute rejection (%) | 28 (22.2) | 17 (18.7) | 0.62 |

| Steroid treated | 12 (42.9) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Thymoglobuin treated | 16 (57.1) | 9 (52.9) |

CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; CsA, cyclosporine; Tac, tacrolimus; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

Clinical Efficacy

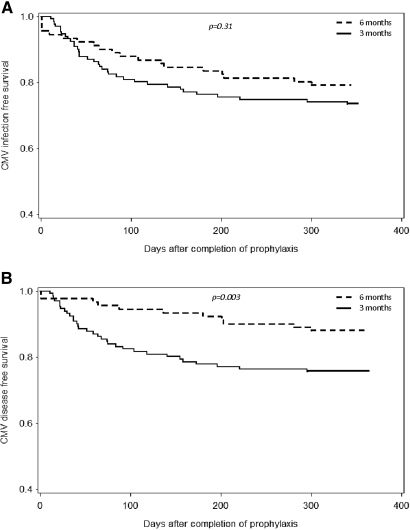

During the entire study period, 54 cases of CMV infection (24.3%) were documented by CMV viremia. The median time to CMV infection was 64 d after completion of prophylaxis with a range from 1 to 340 d after prophylaxis. The majority of cases (43) had CMV disease (19.4%) as defined by either gastroenteritis (84.6%) with/or without hepatitis and pancreatitis, CMV syndrome (7.7%), pneumonitis (2.6%), nephritis (2.6%), and retinitis (2.6%). Only one patient in the 3-mo group died of multiorgan failure as a direct consequence of CMV disease. CMV disease did not occur during the prophylaxis period. Table 2 shows the proportion of overall CMV infection and disease between the two groups and the relative risk as determined by univariate analysis. Six-month prophylaxis with VGCV was associated with a 26% risk reduction in CMV disease (RR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60 to 0.93; P = 0.02), but only a 12% risk reduction in CMV infection (RR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.69 to 1.12; P = 0.32), which was not statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses showed that extending the prophylaxis with VGCV to 6 mo, combined with a protocol-driven determination of CMV viremia, resulted in a statistically significant improvement in disease-free survival (log-rank, P = 0.003) but not in infection-free survival (log-rank, P = 0.31; Figure 1, A and B).

Table 2.

Prophylaxis regimens and CMV infection and disease

| 3-Mo (n = 131) | 6-Mo (n = 91) | RR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV infection (%) | 35 (26.7) | 19 (20.9) | 0.88 (0.69, 1.12) | 0.32 |

| CMV disease (%) | 32 (24.4) | 11 (12.1) | 0.74 (0.60, 0.93) | 0.02 |

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier event-free survival curves for (A) CMV infection and (B) CMV disease.

In the 3-mo group, all cases of CMV viremia were determined as clinically indicated. On the other hand, in the 6-mo group, 67 of 91 patients (73.6%) had a protocol-driven one-time CMV viremia determination at the end of the 6-mo prophylaxis period (median time, 189 d; ranging from 144 to 314 d after transplantation): seven were found positive (10.4%) with only one showing symptoms and an additional seven patients (10.4%) later developed CMV infection through clinically driven viremia determination, with six of them being symptomatic. Among the 24 patients who missed a protocol-driven viremia determination, 5 (20.8%) were subsequently diagnosed with CMV infection and only 1 patient was asymptomatic. Table 3 shows the viremia titers among the patients with CMV infection diagnosed by either clinical or protocol-driven viremia determination and among patients with either asymptomatic infection or disease from both groups. Patients from the 6-mo group who were diagnosed by protocol-driven viremia determination or developed asymptomatic infection had lower viral load than those patients from the 3-mo group diagnosed by clinical-driven viremia determination or had disease (P = 0.008 and P = 0.003, respectively).

Table 3.

CMV viremia titers between the 3- and 6-mo VGCV prophylaxis groups

| 3-Mo Clinical Diagnosis (n = 34) | 6-Mo |

Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol Diagnosis (n = 7) | Clinical Diagnosis (n = 12) | |||

| DNA copy (no./ml) | 109,278 ± 280,863 | 11,921 ± 23,086 | 39,042 ± 39,286 | 0.465 |

| Log10DNA copy (no./ml) | 4.50 ± 0.66 | 3.60 ± 0.61 | 4.22 ± 0.73 | 0.008 |

| Disease (n = 32) | Asymptomatic (n = 8) | Disease (n = 11) | ||

| DNA copy (no./ml) | 115,833 ± 288,478 | 11,719 ± 21,403 | 41,654 ± 40,088 | 0.427 |

| Log10DNA copy (no./ml) | 4.56 ± 0.64 | 3.64 ± 0.61 | 4.25 ± 0.74 | 0.003 |

aANOVA.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed adjusting for various demographic and baseline clinical characteristics such as age, gender, race, acute rejection before CMV infection, number of transplants, type of transplant, underlying kidney diagnosis, use of different CNIs, use of MMF, and transplant era (divided into quartiles). The only factors responsible for the difference in the incidence of CMV infection and disease were the duration of CMV prophylaxis, the use of induction agents, and possibly the brand of CNIs (Table 4). The 6-mo prophylaxis was associated with significant reduction in the risk for CMV disease (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.17 to 0.72; P = 0.004), although the risk reduction for CMV infection did not achieve statistical significance (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.37 to 1.14; P = 0.129). The use of Thymoglobulin, a T cell–depleting rabbit anti-thymocyte polyclonal antibody, significantly increased the risk of CMV infection (HR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.37 to 4.18; P = 0.002) and disease (HR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.19 to 4.10; P = 0.012). In contrast, the use of basiliximab, an anti-IL-2 receptor monoclonal antibody, had no appreciable effect on the incidence of CMV infection and disease (data not shown). The use of tacrolimus was associated with an increased risk for CMV disease but not overall infection that is nearly statistically significant (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 0.93 to 3.78; P = 0.078).

Table 4.

Clinical predictors of CMV infection and disease

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prophylaxis regimens | Infection | 0.65 (0.37, 1.14) | 0.129 |

| 6-mo versus 3-mo | Disease | 0.35 (0.17, 0.72) | 0.004 |

| Induction regimens | Infection | 2.39 (1.37, 4.18) | 0.002 |

| Thymoglobulin versus no thymoglobulin | Disease | 2.21 (1.19, 4.10) | 0.012 |

| Use of calcineurin inhibitors | Infection | 1.18 (0.60, 2.32) | 0.631 |

| Tac versus CsA | Disease | 1.87 (0.93, 3.78) | 0.078 |

Cost Effectiveness

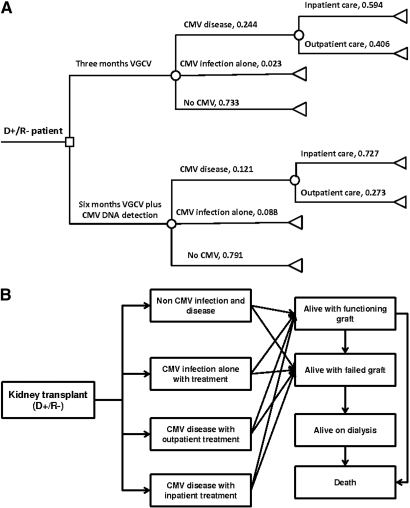

The decision tree and Markov transitional model are shown in Figure 2. We limited our transitional model to four possible health states: no CMV infection, asymptomatic CMV infection, CMV disease with inpatient treatment, and CMV disease with outpatient treatment. Each patient from those four states has the possibility to transition into one of the following substates: alive with functioning graft, alive with failed graft on dialysis, and death. Death may occur with a functioning graft or on dialysis but not as a direct consequence of CMV infection or disease because of the lack of the data on this state. For the decision tree analysis, the clinical outcome derived from our study was used to calculate the costs related to CMV prophylaxis, the diagnosis, and the treatment of CMV infection and/or disease for a patient receiving either 3 or 6 mo of prophylaxis. The quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) and total costs of having a functioning transplant or returning to dialysis over a 10-yr period are calculated based on United States Renal Data System and Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients annual reports with the following assumptions: (1) annual graft loss remains stable throughout the 10-yr period at 5.4% in the absence of CMV infection; (2) asymptomatic CMV infection and CMV disease incur an additional 1.5% and 3.0%, respectively, annual graft loss; (3) one third of graft loss is caused by death with functioning graft and two thirds of patients with graft loss will return back to dialysis; and (4) annual death rate on dialysis remains stable throughout the 10 yr at 13.4%.10,27,28 Table 5 shows the parameters used in the decision tree and Markov transitional model, whereas Table 6 shows the cost-effectiveness results. Six-month CMV prophylaxis offered incremental gain in effectiveness in infection and disease avoided (5.8% and 12.3%, respectively), as well as QALYs gained (0.075) at an additional expense of $1,993 per patient because of the expense incurred by the prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of CMV infection and/or disease. Over the following 10 yr, a patient from the 3-mo group would have spent $432,504, whereas a patient from the 6-mo group would have spent $431,133, both assuming a discount rate of 5%/yr. Thus, the incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER) is $34,362 and $16,215 per case of infection and disease avoided, but only $8,304 per one QALY gained.

Figure 2.

(A) Decision tree with probability for various clinical outcomes and (B) Markov transitional model with four main health states and subsequent substates.

Table 5.

Model parameters applied to the decision tree analysis and Markov model

| Variables | Values | Reference/Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Utility index for a patient with a functioning kidney transplant | 0.73 | (37) |

| Utility index for a patient on dialysis | 0.53 | (37,38) |

| Utility index for death | 0 | |

| Probability of graft failure over 10-yr period | (10,28) and | |

| Without early CMV disease and infection | 0.514 | assumption |

| With early CMV disease | 0.844 | |

| With early CMV infection | 0.714 | |

| Probability of patient death | (27,28) | |

| With a functioning transplant (per year) | 0.018 | |

| On dialysis (per year) | 0.134 | |

| CMV disease | ||

| 3 mo | 0.244 | This study |

| 6 mo + CMV DNA detection | 0.121 | |

| CMV infection (asymptomatic) | ||

| 3 mo | 0.023 | This study |

| 6 mo + CMV DNA detection | 0.088 | |

| Inpatient care for CMV disease | ||

| 3 mo | 0.594 | This study |

| 6 mo + CMV DNA detection | 0.727 | |

| Outpatient management for CMV infection | ||

| 3 mo | 0.406 | This study |

| 6 mo + CMV DNA detection | 0.273 | |

| Cost (in 2007 US dollars) | ||

| VGCV (450-mg tablet) | 36.5 | CMS price |

| CMV DNA quantitation (per test) | 59.85 | CMS price |

| CMV prophylaxis (450 mg/d) | ||

| 3 mo | 3,285 | |

| 6 mo | 6,570 | |

| CMV disease and infectiona | ||

| Inpatient care per day | 3,601 | |

| Inpatient care per patient (4 d) | 14,404 | |

| Medication (3 mo) | 8,103 | |

| Cost for patient with a functioning transplant (per year) | 25,000 | (27) |

| Cost for patient on maintenance dialysis (per year) | 65,000 | (27) |

| Opportunity cost (loss in wage) | ||

| CMV disease requiring inpatient care | 1,400 | Assumption |

| CMV disease not requiring inpatient care | 500 | Assumption |

aDrug treatment: VGCV 900 mg twice daily for 3 wk as induction and 900 mg daily for 9 wk as maintenance.

VGCV, valganciclovir.

Table 6.

Cost-effectiveness results

| 3-Mo | 6-Mo | Incremental Effect and/or Cost | ICER ($/unit) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome per patient | ||||

| Infection avoided | 0.733 | 0.791 | 0.058 | 34,362 |

| Disease avoided | 0.756 | 0.879 | 0.123 | 16,215 |

| QALY gained | 5.600 | 5.675 | 0.075 | 8,304 |

| Cost per patient ($) | ||||

| Direct | 7,720 | 9,713 | 1,993 | |

| Indirect (10 yr) | 432,504 | 431,133 | −1,371 | |

| Total | 440,224 | 440,846 | 622 |

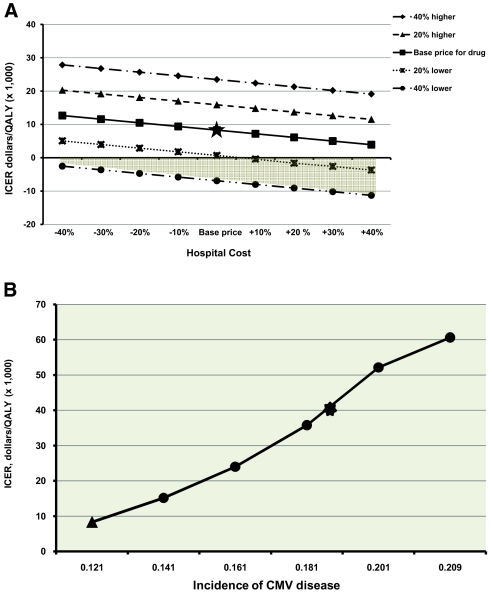

Two-way sensitivity analysis was performed by varying the VGCV and hospital costs. The ICER per QALY gained was sensitive to the changes in the cost of both medication and hospital care (Figure 3A). However, despite the wide range of cost variation from 40% less expensive to 40% more expensive, the ICER did not exceed $30,000 per QALY gained, a cost considered by many as within an acceptable range.29,30 Furthermore, if the price of VGCV decreased by 40%, 6-mo CMV prophylaxis become dominant because it saves money for each one QALY gained, with all variation in hospital cost used in the model. In addition, the ICER was also sensitive to the variation in the rate of CMV disease. For example, as the incidence of CMV disease increases in the 6-mo group, the ICER increases as well (Figure 3B). In fact, if all asymptomatic cases detected by the protocol-driven CMV viremia determination were cases of disease, the ICER would be $40,063 per QALY gained. Only when the incidence of CMV disease equals the incidence of overall CMV infection does the ICER reach $60,000 per QALY gained, an undesirable economic price tag for the 6-mo CMV prophylaxis approach.

Figure 3.

(A) Two-way sensitivity analysis for ICER with varying costs in medication and in hospital admission: shaded area represents the dominant effect of 6-mo CMV prophylaxis. ★, Baseline value for hospital and medication cost. (B) One-way sensitivity analysis for ICER with varying incidence in CMV disease in the 6-mo CMV prophylaxis group. ▴, Actual CMV disease rate in the 6-mo group; *, no protocol-driven viremia determination was performed in the 6-mo group.

Prophylaxis-Related Adverse Effects

The only adverse effect considered was leukopenia. Compared with the 3-mo CMV prophylaxis group, patients receiving 6 mo of VGCV had significantly lower nadir total leukocyte counts during the prophylaxis period (4363 ± 1910 versus 3725 ± 1861, respectively, P = 0.015). Significantly more patients from the 6-mo group experienced leukopenia than from the 3-mo group (64.8% versus 46.8%, respectively, P = 0.009). The use of Thymoglobulin for induction and of MMF for maintenance immunosuppression strongly correlates with the development of leukopenia during the prophylaxis period (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.014, respectively). After adjusting these two, the choice of prophylaxis regimen appeared only marginally associated with the development of leukopenia (P = 0.059). For both groups, management of leukopenia was at the discretion of the individual transplant physicians and included either a temporary reduction or cessation of MMF. Only three patients required the administration of Neupogen for leukopenia as outpatients in the 6-mo CMV prophylaxis group.

Discussion

This study showed that extending VGCV prophylaxis to 6 mo, combined with one-time CMV viremia determination at the end of prophylaxis period, is effective in reducing the incidence of CMV infection and disease in D+/R− kidney and/or pancreas transplant patients. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness analyses showed that such an approach saves dollars per QALY gained over the 10-yr period. The variation in the incidence of CMV disease in the 6-mo group did impact negatively the cost-benefit ratio. However, if all cases of asymptomatic infection progressed to CMV disease because no protocol-driven viremia determination was performed, the ICER would be $40,063 instead of $8,304 per QALY gained by our model. This price tag could still be justifiable.29,30

Previous studies compared CMV prophylaxis using different medications or universal prophylaxis versus pre-emptive treatment and found that prophylaxis resulted in less CMV infection and disease, equal or less cost, and better long-term graft survival.2,18,23–26,31 Most of these studies have included only a limited number of CMV D+/R− patients. A few studies have examined the clinical efficacy of extending the length of CMV prophylaxis in kidney and other organ transplant patients.20,21,32 Doyle et al.32found that 6-mo prophylaxis with GCV was more effective in reducing CMV infection than 3-mo GCV prophylaxis. However, their study used GCV and only included 31 patients with 6 mo of follow-up after prophylaxis. Akalin et al.20 reported a decreased incidence of CMV infection in Thymoglobulin-treated patients with 6 mo of VGCV prophylaxis, but their study population only included four CMV D+/R− patients. Finally, Helantera et al.21 reported that, after 6 mo of VGCV prophylaxis in 25 CMV D+/R− patients, the incidence of CMV disease was as high as 40% by periodic CMV viremia determination. None of these studies assessed the economic impact of extending duration of CMV prophylaxis.

Besides the impact of donor and recipient CMV mismatch, the degree of immunosuppression strongly affects the risk of CMV infection and disease.4,33,34 Our findings clearly showed that the use of T cell–depleting antibodies such as Thymoglobulin increased the risk for CMV infection and disease compared with IL-2 receptor antagonists in CMV D+/R− patients. In addition, our study suggests that the choice of CNIs may influence the risk of CMV disease in this group of patients. In patients who received tacrolimus, the risk of disease was higher than in the cyclosporine-treated patients. This result was not statistically significant, however, possibly because of the relatively fewer number of patients taking tacrolimus.

CMV disease is one of the most common infections after transplantation that require hospitalization, particularly for CMV D+/R− kidney transplant patients.7 Early detection of infection with the use of a one-time protocol-driven CMV viremia determination allowed us to diagnose asymptomatic CMV infection in 6 of 67 patients who were all treated as outpatients. This approach has surely contributed to the observed cost-effective benefit in the 6-mo prophylaxis group. The CMV viremia titer was significantly lower in asymptomatic patients and in those patients diagnosed by protocol CMV viremia determination. Our observation is consistent with a previous report that CMV DNA titer is a predictor of CMV disease.35

The main strength of our study includes the large number of CMV D+/R− patients, a considerable number of CMV infection and disease cases, and a detailed economic assessment using standardized cost-effectiveness models.

Our study has a number of limitations. This study compared two sequential cohorts over two different time periods; thus, an era effect could potentially bias the results despite the use of a Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for time and inclusion of era as one of the covariates in the model. In fact, the use of immunosuppression between the two groups varied significantly over time: the use of induction therapy, particularly rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, MMF, and the combination of tacrolimus and MMF, occurred more frequently in the 6-mo prophylaxis group. The implementation of protocol driven one-time CMV viremia determination at the end of prophylaxis in 6-mo group may have resulted in more cases of CMV infection and disease being detected. Nonetheless, either bias should have diluted the magnitude of our findings. Our cost-effectiveness analysis was limited to the major outcomes related to the impact of CMV infection and disease on kidney transplant survival where data were available in the literature. For example, we did not consider the economic impact of CMV infection and disease on the increased rate of allograft rejection and the expense related to its diagnosis and treatment.8,24 By reducing the incidence of CMV infection and disease, one would anticipate a reduction in acute rejection rates that would make the cost effectiveness of 6-mo CMV prophylaxis more favorable. In addition, because the outpatient treatment consisted of a course of oral VGCV, we could not verify for each individual patient their utilization of home health care. By not including this aspect in our analysis, we may have underestimated the magnitude of cost effectiveness in our study.

In conclusion, our study suggests that, in CMV D+/R− kidney and/or pancreas transplant patients, extending prophylaxis with VGCV to 6 mo combined with CMV DNA viremia determination at the end of prophylaxis has the potential to reduce CMV infection and disease with a positive economic benefit. However, the rate of CMV infection and disease still remains unacceptably high. Additional studies are needed to test newer approaches to further reduce the incidence of CMV disease, which can have a significant impact on long-term graft and patient survival.

Concise Methods

Study Design and Patients

This is a retrospective study of a single center experience involving all de novo kidney and/or pancreas transplant patients who were CMV negative by serology before transplant and received an organ from a CMV-positive donor (D+/R−) between March 1, 2002 and March 31, 2007. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

From March 1, 2002 to September 30, 2005, all CMV D+/R− patients received VGCV prophylaxis at a dose of 450 mg daily for 3 mo after transplantation (3-mo group). Despite 3 mo of prophylaxis, the incidence of CMV disease remained elevated.36 Thus, beginning October 1, 2005, a new clinical protocol was instituted for all CMV D+/R− patients to receive VGCV prophylaxis (450 mg daily) for 6 mo in addition to a protocol-driven one-time CMV viremia determination performed at the end of 6-mo prophylaxis period (6-mo group).

All patients were followed for 1 yr after the completion of prophylaxis. The duration of follow-up from the time of transplantation thus was 15 mo for patients in the 3-mo group and 18 mo for patients in the 6-mo group.

Patients who died before completion of CMV prophylaxis were excluded, and none of them had documented CMV infection or disease.

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression was provided according to institutional protocols that included a CNI (cyclosporine or tacrolimus), an anti-proliferative (MMF or sirolimus) and prednisone. Target trough levels for cyclosporine and tacrolimus were 150 to 300 and 5 to 15 ng/ml, respectively, during the first 3 mo. Subsequently, cyclosporine and tacrolimus trough levels were maintained at 100 to 150 and 5 to 8 ng/ml, respectively. Prednisone was tapered to 10 mg/d at about 6 wk after transplant and remained at that dose over the study period. Induction agents, either T cell–depleting rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin) or anti-IL-2 receptor antibody (basiliximab) were used for patients at increased immunological risk for rejection according to the center protocols.

Study Assessments

The primary endpoint was the incidence of CMV infection, defined as viremia using CMV DNA determination by PCR, regardless of the presence of symptoms and/or signs within the first 12 mo after completion of VGCV prophylaxis. The secondary endpoint was the incidence of CMV disease, defined as CMV viremia with symptoms and/or signs of organ involvement. All patients with a diagnosis of CMV disease or infection were treated with an additional course of either intravenous GCV or oral VGCV. Any hospital admission related to CMV disease was recorded, and average length of hospital stay was calculated for all admissions.

Adverse Events Related to Prophylaxis

The lowest white blood cell counts during the entire period of CMV prophylaxis were recorded, and appropriate intervention was documented. Leukopenia was defined as a total white blood cell count less than 4000/μl. The management of leukopenia was recorded including the use of filgrastim (Neupogen) in some cases.

Cost-Effectiveness Analyses

Two types of costs were considered: direct and indirect. Direct costs included all of the expenses incurred in the prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of CMV disease and infection. These costs included the following: VGCV used for prophylaxis and treatment of CMV infection and disease, PCR for CMV viremia determination, filgrastim injections, hospital admissions, and opportunity costs. The opportunity costs were assumed as the following: 5 and 10 working days were lost for patients with CMV disease without and with a hospital admission, respectively; 4 working days were lost for a family member of those patients requiring hospital admission. For patients with an asymptomatic CMV infection, no opportunity costs were incurred. Because the outpatient treatment consisted of oral VGCV, the cost of home health care was not considered. The price of 2007 was used for all patients; thus, no discount rate was applied. Indirect costs included all of the expenses that are associated with maintaining a patient who has a functioning graft or a patient who lost graft function and has returned to dialysis over the next 10-yr period, and a discount rate of 5% was used.

A decision tree was constructed based on the clinical outcomes, and the cost per patient between the two groups was calculated. The ICER was calculated using the following formula:

|

The Markov transitional model was used to develop four main health states: patients with no CMV infection, asymptomatic CMV infection, CMV disease with outpatient treatment, and CMV disease with inpatient treatment. Each patient from any of those four main health states can transition into the following substates: alive with a functioning graft, dead with a functioning graft, alive with a failed graft on dialysis, and dead after returning back to dialysis. The issue of re-transplantation was not modeled into this study. Respective utility indexes were obtained from the literature: for instance, a transplant patient living with a functioning graft was found to have a utility value of 0.73 and a patient on dialysis has a utility value of 0.50 to 0.57.37,38 We limited our cost-effectiveness analyses to the impact of uncensored graft loss, taking into consideration patient survival with a kidney transplant and with dialysis.10,34 The rate of graft loss related to early CMV disease and infection was assumed to be constant over the following 10 yr at an estimate rate of 3.0% and 1.5% per year, respectively.10 These are in addition to the annual graft loss rate of 5.4% in patients with no CMV infection. The 10-yr kidney and patient survival data were obtained from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients 2008 annual report.28 Similarly, the United States Renal Data System 2008 annual report provided survival data on patients undergoing dialysis for 5 and 10 yr.27 The incidences of CMV infection and disease from this study were used to calculate QALYs accumulated over the following 10 yr between the two groups. We did not consider the direct effect of CMV infection and disease on patient survival, both short and long term, because deaths related directly to CMV disease/infection are few, and the actual data on such probability are lacking.

Statistical Analysis

t tests and χ2 tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively, for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between the two groups. The ANOVA technique was applied wherever appropriated. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the incidences of CMV infection and disease. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was used to identify the risk factors for both CMV infection and disease. Linear regression analysis was used to assess the predictors of leukopenia during the prophylaxis period. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were presented in the poster session at the American Transplant Congress, 2008, Toronto, Canada, and in the oral session at the American Transplant Congress, 2009, Boston, MA.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Rubin RH: Impact of cytomegalovirus infection on organ transplant recipients. Rev Infect Dis 12[Suppl 7]: S754–S766, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paya C, Humar A, Dominguez E, Washburn K, Blumberg E, Alexander B, Freeman R, Heaton N, Pescovitz MD: Efficacy and safety of valganciclovir vs. oral ganciclovir for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 4: 611–620, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnitzler MA, Lowell JA, Hardinger KL, Boxerman SB, Bailey TC, Brennan DC: The association of cytomegalovirus sero-pairing with outcomes and costs following cadaveric renal transplantation prior to the introduction of oral ganciclovir CMV prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 3: 445–451, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akalin E, Sehgal V, Ames S, Hossain S, Daly L, Barbara M, Bromberg JS: Cytomegalovirus disease in high-risk transplant recipients despite ganciclovir or valganciclovir prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 3: 731–735, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson PC, Lewis RM, Golden DL, Oefinger PE, Van Buren CT, Kerman RH, Kahan BD: The impact of cytomegalovirus infection on seronegative recipients of seropositive donor kidneys versus seropositive recipients treated with cyclosporine-prednisone immunosuppression. Transplantation 45: 116–121, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S, Mitchell JD, Markham DW, Mammen PP, Patel PC, Kaiser P, Ring WS, DiMaio JM, Drazner MH: High incidence of cytomegalovirus disease in D+/R- heart transplant recipients shortly after completion of 3 months of valganciclovir prophylaxis. J Heart Lung Transplant 27: 536–539, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbott KC, Hypolite IO, Viola R, Poropatich RK, Hshieh P, Cruess D, Hawkes CA, Agodoa LY: Hospitalizations for cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation in the United States. Ann Epidemiol 12: 402–409, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagedal S, Nordal KP, Hartmann A, Sund S, Scott H, Degre M, Foss A, Leivestad T, Osnes K, Fauchald P, Rollag H: The impact of cytomegalovirus infection and disease on rejection episodes in renal allograft recipients. Am J Transplant 2: 850–856, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis RM, Johnson PC, Golden D, Van Buren CT, Kerman RH, Kahan BD: The adverse impact of cytomegalovirus infection on clinical outcome in cyclosporine-prednisone treated renal allograft recipients. Transplantation 45: 353–359, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagedal S, Hartmann A, Nordal KP, Osnes K, Leivestad T, Foss A, Degre M, Fauchald P, Rollag H: Impact of early cytomegalovirus infection and disease on long-term recipient and kidney graft survival. Kidney Int 66: 329–337, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCarthy JM, Karim MA, Krueger H, Keown PA: The cost impact of cytomegalovirus disease in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation 55: 1277–1282, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsevat J, Snydman DR, Pauker SG, Durand-Zaleski I, Werner BG, Levey AS: Which renal transplant patients should receive cytomegalovirus immune globulin? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Transplantation 52: 259–265, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legendre CM, Norman DJ, Keating MR, Maclaine GD, Grant DM: Valaciclovir prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in renal transplantation: An economic evaluation. Transplantation 70: 1463–1468, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pescovitz MD, Rabkin J, Merion RM, Paya CV, Pirsch J, Freeman RB, O'Grady J, Robinson C, To Z, Wren K, Banken L, Buhles W, Brown F: Valganciclovir results in improved oral absorption of ganciclovir in liver transplant recipients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44: 2811–2815, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luan FL, Chopra P, Park J, Norman S, Cibrik D, Ojo A: Efficacy of valganciclovir in the treatment of cytomegalovirus disease in kidney and pancreas transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 38: 3673–3675, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asberg A, Humar A, Rollag H, Jardine AG, Mouas H, Pescovitz MD, Sgarabotto D, Tuncer M, Noronha IL, Hartmann A: Oral valganciclovir is noninferior to intravenous ganciclovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 7: 2106–2113, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamberlain CE, Penzak SR, Alfaro RM, Wesley R, Daniels CE, Hale D, Kirk AD, Mannon RB: Pharmacokinetics of low and maintenance dose valganciclovir in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 8: 1297–1302, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kliem V, Fricke L, Wollbrink T, Burg M, Radermacher J, Rohde F: Improvement in long-term renal graft survival due to CMV prophylaxis with oral ganciclovir: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Transplant 8: 975–983, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arthurs SK, Eid AJ, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Cosio FG, Patel R, Razonable RR: Delayed-onset primary cytomegalovirus disease and the risk of allograft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 46: 840–846, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akalin E, Bromberg JS, Sehgal V, Ames S, Murphy B: Decreased incidence of cytomegalovirus infection in Thymoglobulin-treated transplant patients with 6 months of valganciclovir prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 4: 148–149, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helantera I, Lautenschlager I, Koskinen P: Prospective follow-up of primary CMV infections after 6 months of valganciclovir prophylaxis in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 316–320, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller GG, Kaplan B: Prophylaxis versus preemptive protocols for CMV: Do they impact graft survival? Am J Transplant 8: 913–914, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoury JA, Storch GA, Bohl DL, Schuessler RM, Torrence SM, Lockwood M, Gaudreault-Keener M, Koch MJ, Miller BW, Hardinger KL, Schnitzler MA, Brennan DC: Prophylactic versus preemptive oral valganciclovir for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in adult renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 6: 2134–2143, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reischig T, Jindra P, Hes O, Svecova M, Klaboch J, Treska V: Valacyclovir prophylaxis versus preemptive valganciclovir therapy to prevent cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. Am J Transplant 8: 69–77, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalil AC, Levitsky J, Lyden E, Stoner J, Freifeld AG: Meta-analysis: The efficacy of strategies to prevent organ disease by cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med 143: 870–880, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodson EM, Craig JC, Strippoli GF, Webster AC. Antiviral medications for preventing cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD003774, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.US Renal Data System: USRDS 2007 Annual Data Report, Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease; Available at http://www.usrds.org/adr.htm Accessed September 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28.OPTN/SRTR: 2007 Annual Report, Rockville, Department of Health and Human Service, Division of Transplantation; Available at http://www.ustransplant.org/annual_reports/current/ Accessed September 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC: Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine New York: Oxford University Press; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearson SD, Rawlins MD: Quality, innovation, and value for money: NICE and the British National Health Service. JAMA 294: 2618–2622, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauskopf JA, Richter A, Annemans L, Maclaine G: Cost-effectiveness model of cytomegalovirus management strategies in renal transplantation. Comparing valaciclovir prophylaxis with current practice. Pharmacoeconomics 18: 239–251, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doyle AM, Warburton KM, Goral S, Blumberg E, Grossman RA, Bloom RD: 24-week oral ganciclovir prophylaxis in kidney recipients is associated with reduced symptomatic cytomegalovirus disease compared to a 12-week course. Transplantation 81: 1106–1111, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Maar EF, Verschuuren EA, Homan vd Heide JJ, Kas-Deelen DM, Jagernath D, The TH, Ploeg RJ, van Son WJ: Effects of changing immunosuppressive regimen on the incidence, duration, and viral load of cytomegalovirus infection in renal transplantation: A single center report. Transplant Infect Dis 4: 17–24, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.San Juan R, Aguado JM, Lumbreras C, Fortun J, Munoz P, Gavalda J, Lopez-Medrano F, Montejo M, Bou G, Blanes M, Ramos A, Moreno A, Torre-Cisneros J, Carratala J: Impact of current transplantation management on the development of cytomegalovirus disease after renal transplantation. Clin Infect Dis 47: 875–882, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rollag H, Sagedal S, Kristiansen KI, Kvale D, Holter E, Degre M, Nordal KP: Cytomegalovirus DNA concentration in plasma predicts development of cytomegalovirus disease in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect 8: 431–434, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JM, Luan FL: Incidence and risk factors of cytomegalovirus disease in adult kidney or simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant recipients who received valgancyclovir prophylaxis. Am J Transplant 6: 587, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, Krueger H, Ferguson B, Wong C, Muirhead N: A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Int 50: 235–242, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Narayan R, Perkins RM, Berbano EP, Yuan CM, Neff RT, Sawyers ES, Yeo FE, Vidal-Trecan GM, Abbott KC: Parathyroidectomy versus cinacalcet hydrochloride-based medical therapy in the management of hyperparathyroidism in ESRD: A cost utility analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 49: 801–813, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]