Abstract

Purpose

We compared the prophylactic effects of intravenously administered azasetron (10 mg) and ondansetron (8 mg) on postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia.

Materials and Methods

We studied 98 ASA physical status I or II 20-65 years old, female patients, in this prospective, randomized, double blind study. Patients were randomly divided into two groups and received ondansetron 8 mg (group O) or azasetron 10 mg (group A) 5 min before the end of surgery. The incidence of PONV, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain, need for rescue antiemetic and analgesics, and adverse effects were checked at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively.

Results

The overall incidence of PONV was 65% in group O and 49% in group A. The incidence of PONV was significantly higher in group O than in group A at 12-24 h postoperatively (nausea; 24% vs. 45%, p = 0.035, vomiting; 2% vs. 18%, p = 0.008), but there were no significant differences at 0-1, 1-6, 6-12 or 24-48 h.

Conclusion

In conclusion, azasetron (10 mg) produced same incidence of PONV as ondansetron (8 mg) in patients undergoing general anesthesia for gynecological laparoscopic surgery. Azasetron was more effective, in the intermediate post-operative period, between 12 and 24 h.

Keywords: Azasetron, gynecologic surgical procedures, ondansetron, postoperative nausea and vomiting, prophylaxis

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a common, distressing complication after anesthesia and surgery, with an overall incidence of 30-70% after general anesthesia.1 Most (54-92%) patients undergoing gynecological laparoscopic surgery with general anesthesia experience PONV,2 justifying the use of prophylactic antiemetics. Selective serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] subtype 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonists can safely and effectively prevent PONV. Indeed, PONV guidelines include the use of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists as the first-line preventive agents in high-risk patients.3

Ondansetron, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, has prophylactic antiemetic effects after a single administration before or after surgery.4 Azasetron, a selective potent 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, is a derivative of benzamide with chemical structure different from other 5-HT3 receptor antagonists such as granisetron, ondansetron, ramosetron and tropisetron.5 Azasetron has a longer duration of action6 and a higher affinity to the 5HT3 receptor.7 Azasetron has already been shown to be highly effective in the prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting induced by anticancer drugs.8,9 However, the prophylactic effects of azasetron on PONV is unknown.

Here, we compared the prophylactic antiemetic effect of intravenously administered azasetron (10 mg) and ondansetron (8 mg) by comparing the incidence of PONV and the use of rescue antiemetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After Institutional Ethics Committee approval and informed consent, we studied 98 patients with American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I or II, between the ages of 20 and 65 years, and undergoing general anesthesia for gynecological laparoscopic surgery (total hysterectomy). Exclusion criteria included the use of antiemetics within 24 h prior to surgery, the presence of a gastrointestinal disease, concurrent menstruation, a history of motion sickness, smoking, or previous PONV. No patients received preanesthetic medication. Standard anesthetic regimens and techniques were used for all patients. Anesthesia was induced with propofol (2 mg/kg), and tracheal intubation was facilitated with rocuronium 0.9 mg/kg. Anesthesia was maintained with 66% nitrous oxide in oxygen and 2-3% (inspired concentration) sevoflurane. All patients were monitored with continuous ECG, blood pressure oscillometry, pulse oximetry and capnometry during the surgery. End expiratory carbon dioxide was maintained at 30-35 mmHg. Arterial blood pressure and heart rate were kept within 20% of preanesthetic values. In all patients, lactated Ringer's solution was administered at a rate of 8 mL/kg/hour. A nasogastric tube was inserted so that the gastric contents could be suctioned after anesthetic induction. At 5 min before the end of surgery, patients intravenously received either ondansetron (Zofran®, GlaxoSmithKline, North Carolina, USA) 8 mg (Group O) or azasetron (Seroton®, Welfide, Co., Osaka, Japan) 10 mg (Group A), from identical syringes. A nurse, not participating in patient evaluation, prepared the study drugs from instructions in numbered, sealed envelopes, assigned by random numbers generated by a computer. At the end of surgery, patients received pyridostigmine (15 mg) and glycopyrrolate (0.5 mg) for reversal of neuromuscular blockade. Before tracheal extubation, the nasogastric tube was suctioned and removed. For postoperative pain control, all patients received a bolus of nalbuphine (10 mg) at 30 min before the end of surgery. By using the continuous balloon type infuser (REF C0020M, Wooyoung Medical, Seoul, Korea), 50 mg of nalbuphine and 150 mg of ketorolac, diluted in 100 mL of 5% glucose solution, were infused continuously at 2 mL/h for 2 days. If a patient complained of pain and requested additional analgesics, 10 mg of nalbuphine was injected intravenously. Patients were interviewed by an anesthesiologist (who was blind to the study drug) at 1, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h to assess nausea and vomiting. Only 2 possible answers were accepted (yes or no). Nausea was defined as subjective sensation of discomfort associated with the awareness of the urge to vomit. Vomiting was defined as a forceful expulsion of gastric contents through the mouth. PONV rescue medication (metoclopramide 10 mg IV) was delivered under the following conditions: when nausea was intractable, three or more emetic episodes within 15 minutes, or whenever patients requested medication. Patients who experienced nausea or vomiting at least once during 48 h after surgery were scored positive for PONV incidence.

Pain was recorded at 1, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS; where 0 = no pain and 10 = worst possible pain) at rest, and the need for nalbuphine IV was recorded. Headache and other adverse effects (i.e., dizziness, constipation) were also registered as present or absent during 48 h after surgery.

A power analysis was performed while designing the study. Allowing an α error of 5% and β error of 20%, it was estimated that a minimum of 42 patients per group would be required to show a 27% difference in the incidence of PONV.10

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 15 (Statistical Package for Social Science, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to test continuous variables with an independent t-test, and non-continuous, independent variables with Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. The values were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number of patients (%). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

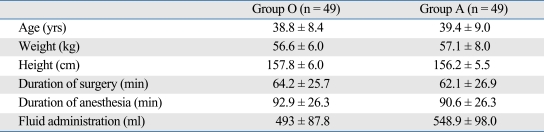

Patient groups did not show differences in age, body weight, height, operation time, anesthesia time, or the amount of infused solution (Table 1). All patients were non-smoking females who received laparoscopic gynecological surgery and postoperative pain control with opioid analgesics. According to Apfel's score,11 these three risk factors place them at a high risk for PONV.

Table 1.

Demographic and Anesthesia Data

Values are mean ± SD or number of patients.

Group O, ondansetron group; Group A, azasetron group.

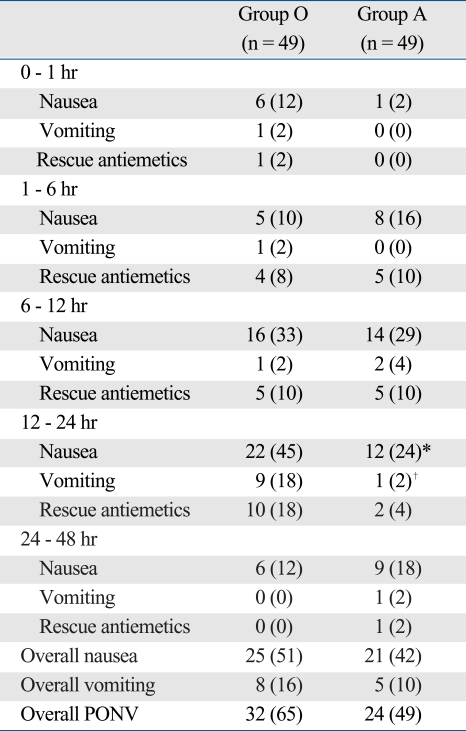

The overall incidence of PONV was 65% in group O and 49% in group A. The incidence of nausea at 12-24 h was significantly lower in group A than group O (24% vs. 45%, p = 0.035) (Table 2). Vomiting incidence during 12-24 h was significantly lower in group A than in group O (2% vs. 18%, p = 0.008) (Table 2). The need of rescue antiemetics in 12-24 hours was lower in group A than group O (4% vs. 18%), but not significantly. Other time periods showed no significant differences, and there were no differences in the number of patients that requested rescue antiemetics (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting and Need for Rescue Antiemetics

PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; Group O, ondansetron group; Group A, azasetron group.

Values are number of patient (%).

Overall PONV, defined as the % of patients who experience nausea or vomiting at least once during 48 h after surgery.

*p = 0.035 vs. Group O.

†p = 0.008 vs. Group O.

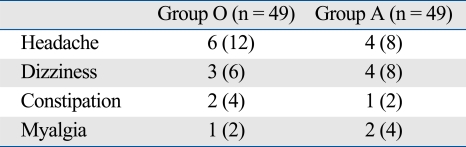

VAS tended to decrease in both groups with time, with no significant difference between the two groups. Similar numbers of patients requested additional analgesics, and the total amount of rescue nalbuphine was similar (150 mg vs. 170 mg, p > 0.05). The incidence rate of adverse effects (headache, dizziness, and constipation) was not significantly different between two groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Incidence of Adverse Effects

Values are number of patient (%) Group

O, ondansetron group; Group A, azasetron group.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, ondansetron and azasetron showed similar levels of control in overall PONV (49% vs. 65%), however, the incidence of nausea and vomiting at 12-24 h after surgery was significantly lower in the azasetron group. Low-dose 5-HT3 antagonists have been shown to effectively, safely, and cost-effectively induce PONV prophylaxis as a monotherapy at the end of anesthesia.12-16 5-HT3 receptor antagonists selectively and competitively bind to 5-HT3 receptors, blocking serotonin binding at vagal afferents in the gut and in the regions of the CNS involved in emesis, including the chemoreceptor trigger zone and the nucleus tractus solitarii.17 However, differences in efficacy of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are still unclear. These differences may involve multiple factors such as intrinsic differences in 5-HT3 receptor blocking activity, 5-HT3 receptor affinity and binding stability, and differences in autocrine activity of serotonin released from enterochromaffin (EC) cells to act on 5-HT3 or 5-HT4 receptors on EC cells.18

Ondansetron was the first member of this group to be marketed,19 and the recommended IV dose (4-8 mg) is most effective when administered just after the completion of surgery because of its short duration of effect.13 Its anti-vomiting effect is stronger than its antinausea effect.20 Haga, et al.6 have shown that azasetron is more effective than ondansetron on cisplatin-induced vomiting in dogs. Fukuda, et al.21 reported that a single bolus injection of azasetron completely inhibited cisplatin-induced emesis for 24 h in dogs.

In the present study, azasetron reduced PONV for 12-24 hours significantly more than ondansetron, and tended to reduce the need for rescue antiemetics. This difference could result from the longer half life of azasetron, (5.4 h), versus ondansetron (3.2 h),6 and delayed gastric emptying improved by azasetron.22,23

Even with ondansetron and azasetron as prophylactic antiemetics, most patients experienced PONV (49-65%), perhaps because overall PONV incidence was defined as one incident of nausea or vomiting over 48 h, or the high-risk nature of the patients. There was no difference in risk factors between the two groups. Continuous infusion of nalbuphine for 48 h for postoperative pain control greatly increases the incidence of PONV, with an incidence similar to morphine and fentanyl.24,25

Wu, et al.26 reported a 46% PONV rate after ondansetron in high risk patients who received laparoscopic gynecological surgery, and Goll, et al.27 reported a 44% PONV rate with ondansetron in similar patients, which corresponds with our PONV incidence rates. The present study showed that patients were still at high risk of PONV after prophylactic treatment with ondansetron or azasetron, suggesting that prophylactic treatment of PONV with only 5-HT3 receptor antagonists is not enough.

As far as we are aware of, this is the first study to evaluate the use of azasetron for PONV. The dose of ondansetron used in this study was based on the optimal dose for prophylaxis of PONV22,28 and the dose of azasetron was based on the standard single bolus dose for prevention of anticancer agent-induced nausea and vomiting.8,9

The present study has several limitations. When performing power analysis, the expected incidence of PONV was estimated with high risk PONV patients, not with patients receiving identical surgery types. Also, expected PONV reductions were not inferred from studies on same drugs. Future studies with more patients are necessary. In the current study, although PONV incidence in untreated patients is unknown, we thought that it would be unethical not to provide prophylactic therapy for high risk patients to prevent or to reduce PONV.

In conclusion, azasetron (10 mg) produced an incidence of PONV similar to ondansetron (8 mg) in patients undergoing general anesthesia for gynecological laparoscopic surgery. In the intermediate post-operative period, (between 12 and 24 h), azasetron was more effective.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gan TJ. Postoperative nausea and vomiting--can it be eliminated? JAMA. 2002;287:1233–1236. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ismail S. Practice of use of antiemetic in patients for laparoscopic gynaecological surgery and its impact on the early (1st two hrs) postoperative period. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:203–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, Chung F, Davis PJ, Eubanks S, et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62–71. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000068580.00245.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White PF, Watcha MF. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: prophylaxis versus treatment. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:1337–1339. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsukagoshi S. [Pharmacokinetics of azasetron (Serotone), a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist.] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1999;26:1001–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haga K, Inaba K, Shoji H, Morimoto Y, Fukuda T, Setoguchi M. The effects of orally administered Y-25130, a selective serotonin3-receptor antagonist, on chemotherapeutic agent-induced emesis. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1993;63:377–383. doi: 10.1254/jjp.63.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakamori M, Takehara S, Setoguchi M. [High affinity binding of Y-25130 for serotonin 3 receptor.] Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1992;100:137–142. doi: 10.1254/fpj.100.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayakawa T, Sato M, Konaka M, Makino A, Hirohata T, Totsu S, et al. [Comparison of ramosetron and azasetron for prevention of acute and delayed cisplatin-induced emesis in lung cancer patients.] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2006;33:633–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura E, Niimi S, Watanabe A, Tanaka T. [Clinical effect of two azasetron treatment methods against nausea and vomiting induced by anticancer drugs including CDDP.] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1997;24:855–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatnagar S, Gupta D, Mishra S, Srikanti M, Singh M, Arora R. Preemptive antiemesis in patients undergoing modified radical mastectomy: oral granisetron versus oral ondansetron in a double-blind, randomized, controlled study. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apfel CC, Läärä E, Koivuranta M, Greim CA, Roewer N. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krobbuaban B, Pitakpol S, Diregpoke S. Ondansetron vs. metoclopramide for the prevention of nausea and vomiting after gynecologic surgery. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandhu T, Tanvatcharaphan P, Cheunjongkolkul V. Ondansetron versus metoclopramide in prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective double-blind randomized study. Asian J Surg. 2008;31:50–54. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(08)60057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oksuz H, Zencirci B, Ezberci M. Comparison of the effectiveness of metoclopramide, ondansetron, and granisetron on the prevention of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:803–808. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diemunsch P, Gan TJ, Philip BK, Girao MJ, Eberhart L, Irwin MG, et al. Single-dose aprepitant vs ondansetron for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial in patients undergoing open abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:202–211. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee Y, Wang PK, Lai HY, Yang YL, Chu CC, Wang JJ. Haloperidol is as effective as ondansetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:349–354. doi: 10.1007/BF03022656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gan TJ. Selective serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for postoperative nausea and vomiting: are they all the same? CNS Drugs. 2005;19:225–238. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovac AL. Prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting: controversies in the use of serotonin 5-hydroxytryptamine subtype 3 receptor antagonists. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:304–318. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a review. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:326–341. doi: 10.1007/BF03018236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tramér MR, Reynolds DJ, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Efficacy, dose-response, and safety of ondansetron in prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a quantitative systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1277–1289. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda T, Setoguchi M, Inaba K, Shoji H, Tahara T. The antiemetic profile of Y-25130, a new selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;196:299–305. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90443-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozaki A, Sukamoto T. Improvement of cisplatin-induced emesis and delayed gastric emptying by KB-R6933, a novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Gen Pharmacol. 1999;33:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Odani N, Haga K, Setoguchi M. [Effect of Y-25130 on gastric motility in anesthetized rats.] Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1993;101:17–26. doi: 10.1254/fpj.101.1_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho ST, Wang JJ, Liu HS, Hu OY, Tzeng JI, Liaw WJ. Comparison of PCA nalbuphine and morphine in Chinese gynecologic patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1998;36:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walder B, Schafer M, Henzi I, Tramèr MR. Efficacy and safety of patient-controlled opioid analgesia for acute postoperative pain. A quantitative systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:795–804. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045007795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu O, Belo SE, Koutsoukos G. Additive anti-emetic efficacy of prophylactic ondansetron with droperidol in out-patient gynecological laparoscopy. Can J Anaesth. 2000;47:529–536. doi: 10.1007/BF03018944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goll V, Akça O, Greif R, Freitag H, Arkiliç CF, Scheck T, et al. Ondansetron is no more effective than supplemental intraoperative oxygen for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:112–117. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larijani GE, Gratz I, Afshar M, Minassian S. Treatment of postoperative nausea and vomiting with ondansetron: a randomized, double-blind comparison with placebo. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:246–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]