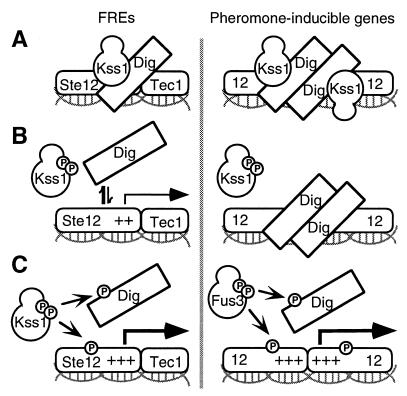

Figure 5.

Model for differential control of FREs and PREs by MAPK- and Dig1/2-mediated regulation. (A) At both elements, unphosphorylated MAPK [principally Kss1 (25–27)] binds directly to Ste12 and to Dig1 (and Dig2), thereby stabilizing Dig1/2–Ste12 complexes and potentiating Dig-mediated repression of Ste12. (B) At FREs, phosphorylation of Kss1 by Ste7, in response to upstream signals, weakens its association with Ste12, consequently promoting dissociation of Dig proteins from Ste12–Tec1 complexes, permitting substantial derepression (27). Ste7-dependent phosphorylation of Kss1 may also attenuate its binding to Ste12 at pheromone-inducible promoters, but this event is not sufficient for effective derepression, presumably because Dig proteins are bound more stably to Ste12–Ste12 homooligomers. (C) At FREs, phosphorylated (activated) Kss1 reinforces the transition, presumably by phosphorylating Dig1/2 (12, 13) and/or Ste12 and/or Tec1 (25, 27). Phosphorylation of these targets may prevent their reassociation, stimulate the transactivator activity of Ste12 and/or Tec1, or both. However, the level of Kss1 activation that results from the signals promoting invasive growth are insufficient to achieve derepression at PRE-bound complexes. In contrast, when more fully activated by pheromone, the MAPKs [principally Fus3 (25, 48)] derepress pheromone-inducible promoters, again presumably by phosphorylating Dig1/2 and Ste12 (11, 12, 13, 24). FRE-bound complexes are apparently insensitive to Fus3 action, perhaps because Fus3 cannot gain access to these complexes or phosphorylate them appropriately.