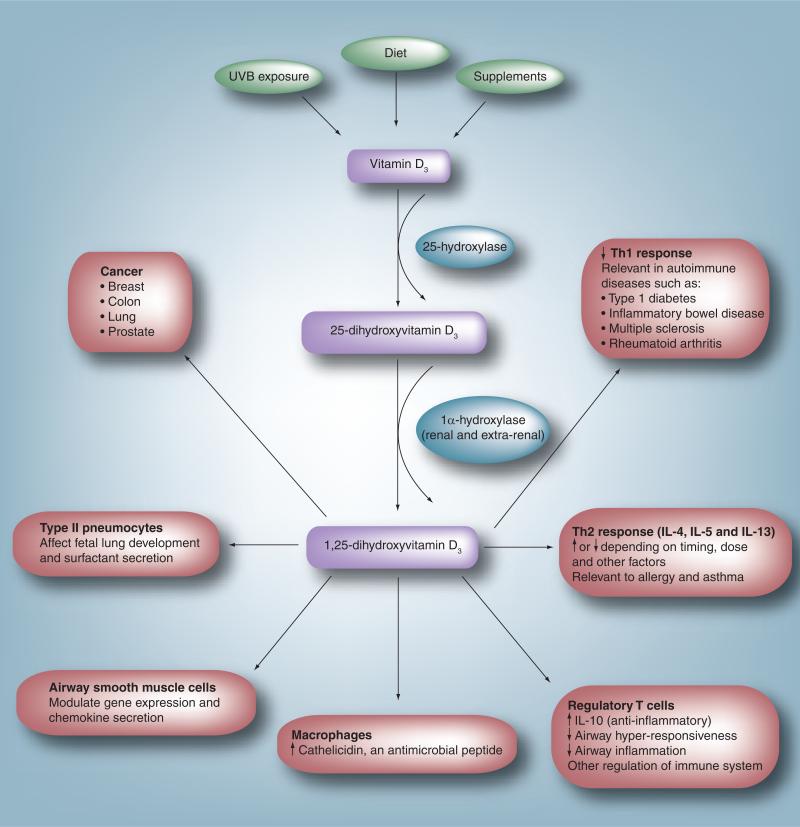

Figure 1. Extraskeletal effects of vitamin D.

In humans, vitamin D is obtained through ultraviolet B exposure, diet and supplement intake. It is converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 by the liver. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 is converted to the active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, in a variety of sites including the kidney and cells of the immune system. Experimental evidence suggests an effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on multiple different processes and cell types. In the immune system it leads to a decrease in the Th1 response, thought to be the mechanism involved in the association between low vitamin D levels and a variety of autoimmune diseases. It modulates the Th2 response affecting cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13. This is one possible link between vitamin D and allergy/asthma. It has been shown to upregulate T-regulatory cells, leading to an increase in the synthesis of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. In macrophages, vitamin D upregulates synthesis of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin, which may enhance the ability to fight infections. In airway smooth muscle cells, it has been shown to modulate chemokine release. Vitamin D may play a role in fetal lung development and in the differentiation of type II pneumocytes and surfactant secretion. Vitamin D has also been associated with a lower incidence of and mortality from a variety of cancers.