Abstract

Deregulation of E2F transcriptional activity as a result of alterations in the p16-cyclin D-Rb pathway is a hallmark of cancer. However, the roles of the different E2F family members in the process of tumorigenesis are still being elucidated. Studies in mice and humans suggest that E2F2 functions as a tumor suppressor. Here we demonstrate that E2f2 inactivation cooperates with transgenic expression of Myc to enhance tumor development in the skin and oral cavity. In fact, hemizygosity at the E2f2 locus was sufficient to increase tumor incidence in this model. Loss of E2F2 enhanced proliferation in Myc transgenic tissue but did not affect Myc-induced apoptosis. E2F2 did not behave as a simple activator of transcription in epidermal keratinocytes but instead appeared to differentially regulate gene expression dependent on the individual target. E2f2 inactivation also altered the changes in gene expression in Myc transgenic cells by enhancing the increase of some genes, such as cyclin E, and reversing the repression of other genes. These findings demonstrate that E2F2 can function as a tumor suppressor in epithelial tissues, perhaps by limiting proliferation in response to Myc.

Introduction

The E2F family of transcription factors regulates the expression of genes involved in cell cycle progression, apoptosis, DNA repair, and differentiation. E2F family members have been divided into several subclasses based on their transcriptional regulatory properties on model gene promoters. E2F1, E2F2, and E2F3a are referred to as “activator” E2Fs because they can potently induce transcription of target genes like cyclin E when overexpressed. These activator E2Fs are expressed in a cell cycle-regulated manner with maximum levels observed in late G1 and early S phase. Based on overexpression experiments, it is thought that activator E2Fs function to drive cell cycle progression and proliferation [1,2]. Another subclass, which includes E2F3b, E2F4, and E2F5, are referred to as the “repressor” E2Fs because their main function appears to be to inhibit transcription of target genes when in association with the retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor or the related pocket proteins, p107 and p130. This repressor subclass is expressed constitutively but transcriptional repression by these E2Fs primarily occurs in quiescent and early G1 phase cells. It is thought that repressor E2Fs function to promote cell cycle exit and maintain quiescence and/or terminal differentiation [3].

The E2F2 gene can be transcriptionally activated by the Myc oncoprotein through functional E box elements in the E2F2 promoter [4]. Initial studies suggested that E2F2 contributes to cellular proliferation induced by Myc [5]. However, more recent findings demonstrate that E2F2’s classification as an activator of transcription and stimulator of proliferation is overly simplistic. For example, while E2f2 inactivation impairs S phase progression in progenitor cells during hematopoiesis, the loss of E2F2 leads to increased proliferation of peripheral T cells coinciding with reduced thresholds for antigen activation [6,7]. Moreover, T cells and embryonic fibroblasts from E2f2−/− mice display increased levels of several E2F targets, including cyclins D1, D3, A2, and B1, CDK1, MCM2 and MCM6 [8]. The E2f1 gene, which is also an E2F target, is also upregulated in T cells lacking E2F2 [6]. Thus, in at least some contexts, E2F2 functions as a repressor of transcription and inhibitor of cell proliferation.

Like E2F1, E2F2 can have either positive or negative effects on tumor development depending on the experimental context [9]. Transgenic mice overexpressing E2F2 in the thymic epithelial compartment have a high incidence of thymoma development [10]. On the other hand, inactivation of E2f2 predisposes mice to hematopoietic malignancies [7]. The absence of E2F2 also accelerates lymphomagenesis in transgenic mice expressing Myc in T cells [11]. Here we further explore the role of E2F2 in tumorigenesis by using the K5.Myc transgenic mouse model in which Myc is overexpressed in the basal layer of squamous epithelial tissues. We find that the absence of E2F2 cooperates with Myc to accelerate tumorigenesis in the skin and oral cavity. This correlates with an enhancement of Myc-induced proliferation and a reversal of Myc-mediated transcriptional repression in the absence of E2F2.

Materials and Methods

Mice

K5.Myc transgenic mice (line 5) have been described [12,13]. E2f2 knock out mice have also been described [5,6] and were a kind gift from Michael Greenberg. The background strain for the K5.Myc mice was SSIN. The strain background for E2f2−/− mice was a mix between 129/Sv and C57/BL. Male K5.Myc mice were bred to mice containing an inactivated E2f2 allele to generate K5.Myc mice hemizygous for E2f2. K5.Myc, E2f2+/− mice were then bred to E2f2+/− mice to generate transgenic and non-transgenic mice wild type, hemizygous, and nullyzygous for E2f2. Sibling mice were used for comparisons in all experiments.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were injected with 170 μl of 20 mM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) 20 min before sacrifice. Skin samples were fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded and sectioned. Skin sections were immunohistochemically stained using an antibody specific for BrdU (Becton Dickson; 1:500 dilution) as previously described [13]. At least 1,000 interfollicular basal layer cells were scored per section to determine the percent that were BrdU-positive. Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded skin sections were also immunohistochemically stained for the activated form of caspase 3 (R & D Systems, 1:2,000 dilution) using the Histostain-Plus kit (Zymed). The average number of caspase 3-positive cells per 10 mm of linear skin was determined for 40 fields per section.

Real time quantitative RT-PCR

Epidermal keratinocytes were isolated from the dorsal skin of adult mice. Dorsal skin samples were incubated in trypsin for 3 h at 30°C after which the epidermis was scraped into Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM). The scraped epidermis was minced, stirred for 30 min at room temperature and strained through a 70-micron filter to remove debris. The cells were then resuspended in 2 ml of EMEM medium and layered onto a 22.5% Percoll gradient, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 15 minutes and the resultant keratinocyte pellet was washed twice in cold PBS.

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit with optional DNaseI treatment (Qiagen, cat. no. 74104). RNA was analyzed for integrity using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). Total RNA (1μg) was then used as template to synthesize cDNA with the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems). qPCR was subsequently performed on the ABI 7900HT Fast Real Time PCR System using a custom TaqMan Low Density Array (Applied Biosystems) containing 93 genes related to cell proliferation and cancer. RNA levels were normalized to the endogenous control gene GAPDH. Data analysis was performed using Sequence Detection System software from ABI, version 2.2.2. The experimental Ct (cycle thresh hold) was calibrated against the GAPDH control product. All amplifications were performed in duplicate. The ΔΔCt method was used to determine the amount of product relative to that expressed by wild type-derived RNA (1-fold, 100%).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed on epidermal lysates using antibodies to cyclin E (Cell Signaling Technology, mouse monoclonal HE12 # 4129, 1:700 dilution) and GAPDH (Abcam Inc., ab9485, 1:10,000 dilution).

Results

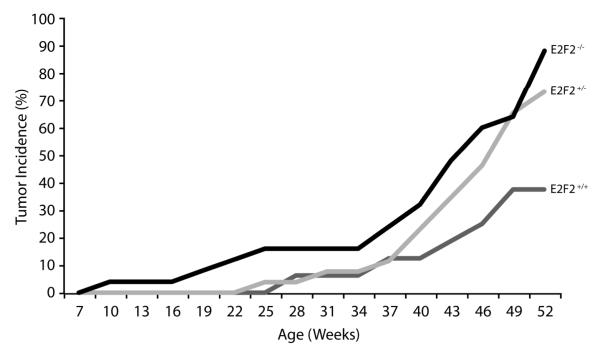

Both E2f1 and E2f2 knockout mice are predisposed to spontaneous tumor development but the specific contexts and mechanisms by which these factors suppress tumorigenesis remain unclear [9]. We previously demonstrated that inactivation of the E2f1 gene in K5.Myc transgenic mice accelerates tumor development [12]. To determine if E2F2 would also behave as a tumor suppressor in this model system, K5.Myc mice were crossed to E2f2−/− mice [5,6]. Similar to previous studies [12,13], 37.5% of K5.Myc mice wildtype for E2f2 developed spontaneous tumors in the skin and oral cavity by one year of age (Figure 1 and Table 1). In the absence of E2f2, tumor incidence increased to 88% of K5.Myc mice by one year of age. Moreover, several K5.Myc, E2f2−/− mice developed multiple tumors while no K5.Myc, E2f2+/+ mice developed more than one tumor. Surprisingly, inactivation of a single E2f2 allele significantly enhanced tumor incidence in K5.Myc transgenic mice. This is in agreement with a recent report demonstrating that inactivation of a single E2f2 allele cooperates with Myc to accelerate lymphoma development [11]. Inactivation of E2f2 did not appear to alter the type of tumors that developed or their invasiveness.

Figure 1. E2f2 deficiency increases tumor incidence in K5.Myc transgenic mice.

K5.Myc transgenic mice wild type (+/+), hemizygous (+/−) or nullizygous (−/−) for E2f2 were monitored for spontaneous tumor development for one year. Tumors arising in K5-expressing epithelial tissues were recorded. The Fisher’s exact test was applied to demonstrate statistically significant differences between E2f2+/+ and E2F2+/− (p <0.05) and E2f2−/− (p <0.001) transgenic mice. The number of mice for each genotype is indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epithelial tumors in K5.Myc transgenic mice

| Genotype | Number of Mice (Gender) |

Tumor incidence at 1 year, % |

Average age of onset, weeks |

Tumor types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E2f2 +/+ | 16 (6 F, 10 M) | 37.5 | 42.6 | One basal cell tumor of the skin and five SCC of oral cavity, of which three were invasive |

| E2f2 +/− | 26 (14 F, 12 M) | 73.1 | 43.6 | One papilloma, five SCC of skin and fourteen SCC of oral cavity, of which six were invasive* |

| E2f2 −/− | 25 (11 F, 14 M) | 88.0 | 40.3 | One papilloma, six SCC of skin and seventeen SCC of oral cavity, of which three were invasive* |

All K5.Myc mice wild type for E2f2 showed only one tumor per mouse, whereas some E2f2 heterozygous and null mice developed more than one tumor per mouse, typically a SCC of skin and SCC of oral cavity. F, female; M, male; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma

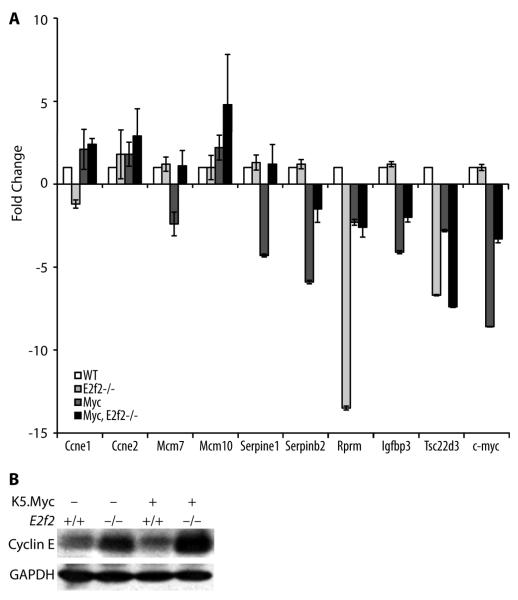

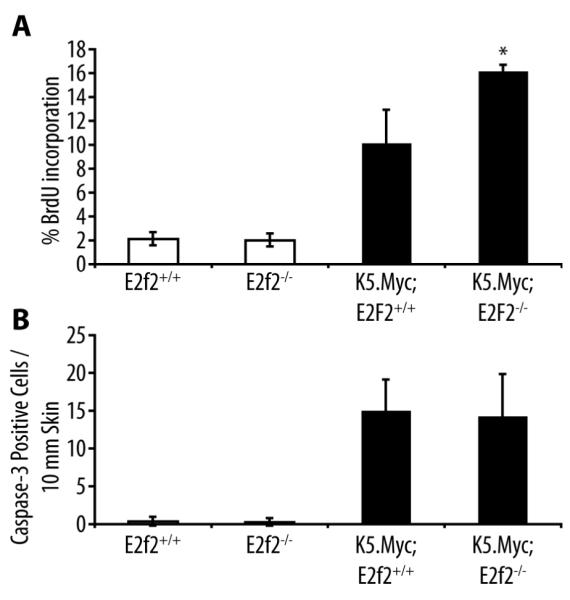

In contrast to the Myc-induced lymphoma model, inactivation of E2f2 enhanced the proliferation index in K5.Myc transgenic epidermis as measured by BrdU incorporation, while Myc-induced apoptosis was unaffected (Figure 2). A previous report suggested that E2F2 inhibited proliferation by transcriptionally repressing a number of cell cycle regulators in both lymphocytes and embryonic fibroblasts [8]. In epidermal keratinocytes, E2f2 inactivation modestly reduced cyclin E1 (Ccne1) expression but enhanced cyclin E2 (Ccne2) expression (Figure 3a). Moreover, inactivation of E2f2 cooperated with the transgenic expression of Myc to further increase cyclin E levels at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 3). The absence of E2F2 also cooperated with Myc to enhance expression of the Mcm10 gene in epidermal keratinocytes (Figure 3a).

Figure 2. Inactivation of E2f2 enhances proliferation in K5.Myc transgenic epidermis.

(A) BrdU incorporation in the epidermis was analyzed by immunohistochemical staining of skin sections from wild type (E2f2+/+), E2f2−/−, K5.Myc, and K5.Myc, E2f2−/− mice. The percentage of BrdU-positive cells in the epidermis was calculated from at least four mice for each genotype. * indicates a statistically significant difference between K5.Myc, E2f2+/+ and K5.Myc, E2f2−/− mice as determined by the student’s paired t-test (p < 0.05). (B) Skin sections from the same mice used above were stained for the activated form of caspase 3 as an indicator of apoptosis. The average number of caspase 3-positive cells per 10 mm of linear epidermis was determined for each genotype.

Figure 3. Inactivation of E2f2 can positively or negatively effect gene expression.

(A) cDNA was made from epidermal keratinocytes isolated directly from mice with the indicated genotypes and used in real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays for the indicated genes. Results are the average of three independent assays performed in duplicate using RNA isolated from 3 different mice of each genotype. Statistically significant differences in expression between wild type and E2f2−/− genotypes were found for Rprm and Tsc22d3 and between K5.Myc, E2f2+/+, and K5.Myc, E2f2−/− genotypes for Serpine1 and Tsc22d3 (paired t-test, p < 0.001). (B) Western blot analysis of epidermal lysates from mice with the indicated genotypes was performed using antibodies specific for cyclin E (recognizes both the cyclin E1 and E2 proteins) and GAPDH as a loading control.

In addition to positively regulating transcription, Myc is also known to repress the transcription of some genes, including the c-myc gene itself [14,15]. Interestingly, inactivation of E2f2 reversed in part the repression of the endogenous c-myc gene in K5.Myc transgenic keratinocytes (Figure 3a). The absence of E2F2 also reversed the Myc-mediated repression of several other genes, including Serpine1, Serpinb2, Mcm7 and Igfbp3. This suggests that E2F2 directly or indirectly contributes to Myc-mediated transcriptional repression of these genes.

On the other hand, E2F2 appears to positively regulate Rprm (Reprimo) and Tsc22d3 in the absence of exogenous Myc expression. Inactivation of E2f2 reduced Rprm and Tsc22d3 expression in epidermal keratinocytes by 13 and 7 fold, respectively (Figure 3a). Both Rprm and Tsc22d3 have been implicated as negative regulators of cell proliferation and are putative tumor suppressor genes.

Discussion

The E2F2 gene is located at human chromosome 1p36, a locus that is frequently lost in a variety of cancers and is thought to harbor multiple tumor suppressor genes [16]. Relevant to our mouse model study, 1p36 is often deleted in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity [17,18]. In neuroblastomas and some other cancers, 1p36 deletion is frequently observed together with amplification of the MYCN gene, suggesting cooperation between increased Myc activity and 1p36 loss [19]. Taken together with our findings, this suggests that the E2F2 gene may function as a tumor suppressor in humans and be a target for deletions associated with chromosome 1p36.

We find that E2f2 inactivation leads to a further increase in epidermal hyperproliferation in K5.Myc transgenic mice. This correlated with increased cyclin E expression in the absence of E2F2, particularly in the presence of the K5.Myc transgene. This contradicts the current model for the E2F family in which E2F2, together with E2F1 and E2F3a, functions to promote cellular proliferation by activating the expression of positive regulators of the cell cycle. Instead, our findings are in agreement with several other studies indicating that E2F2 functions as a negative regulator of cellular proliferation, at least in some contexts [6-8]. The related E2f1 gene has also been shown to function as a tumor suppressor in mouse models, including the K5.Myc model employed here [12]. However, unlike E2f2 inactivation, the absence of E2F1 did not affect Myc-induced proliferation and instead increased Myc-induced apoptosis in transgenic tissue. This suggests that although E2F1 and E2F2 can both function as tumor suppressors, they may inhibit cancer development through distinct mechanisms.

A previous study demonstrated that E2f2 inactivation cooperated with transgenic expression of Myc to induce T cell lymphomagenesis [11]. In agreement with that report, we also find that inactivation of a single E2f2 allele is sufficient to accelerate Myc-driven tumor development. However, in contrast to our findings, inactivation of E2f2 did not affect cell proliferation in Myc transgenic T cells but instead caused decreased levels of apoptosis. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but may be related to cell type-specific functions for E2F2.

In addition to activating transcription, Myc also represses the transcription of some genes and this function is critical for oncogenic transformation by Myc [14,15,20-22]. A number of mechanisms have been proposed for how Myc represses transcription, including interaction with Miz1 and the recruitment of DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a) and histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) [14,23]. A striking finding from our limited gene expression analysis is that the absence of E2F2 reverses, at least in part, the downregulation of several genes in K5.Myc keratinocytes. This includes the endogenous c-myc gene and Serpine1/plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), which is a previously identified target for Myc-mediated transcriptional repression [24]. Further studies will be required to determine how E2F2 participates in the regulation of these Myc-repressed genes and the role this plays in tumor suppression by E2F2.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kevin Lin for statistical analysis, Chris Brown for figure graphics, Shawnda Sanders for preparation of the manuscript, and Jennifer Smith, Pam Blau and John Repass for technical assistance. RW was supported by an American Legion Auxiliary Fellowship and the Sowell Huggins/Sylvan Rodriguez Cancer Answers Scholarship. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants CA079648 (to DGJ), ES007784, and CA016672.

References

- 1.DeGregori J, Leone G, Miron A, Jakoi L, Nevins JR. Distinct roles for E2F proteins in cell growth control and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(14):7245–7250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson DG, Schwarz JK, Cress WD, Nevins JR. Expression of transcription factor E2F1 induces quiescent cells to enter S phase. Nature. 1993;365:349–352. doi: 10.1038/365349a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeGregori J, Johnson DG. Distinct and Overlapping Roles for E2F Family Members in Transcription, Proliferation and Apoptosis. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6(7):739–748. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sears R, Ohtani K, Nevins JR. Identification of Positively and Negatively Acting Elements Regulating Expression of the E2F2 Gene in Response to Cell Growth Signals. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5227–5235. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leone G, Sears R, Huang E, et al. Myc requires distinct E2F activities to induce S phase and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2001;8(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murga M, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Field SJ, et al. Mutation of E2F2 in mice causes enhanced T lymphocyte proliferation, leading to the development of autoimmunity. Immunity. 2001;15(6):959–970. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00254-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu JW, Field SJ, Gore L, et al. E2F1 and E2F2 determine thresholds for antigen-induced T-cell proliferation and suppress tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(24):8547–8564. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8547-8564.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Infante A, Laresgoiti U, Fernandez-Rueda J, et al. E2F2 represses cell cycle regulators to maintain quiescence. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(24):3915–3927. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.24.7379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson DG, Degregori J. Putting the Oncogenic and Tumor Suppressive Activities of E2F into Context. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6(7):731–738. doi: 10.2174/1566524010606070731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheijen B, Bronk M, van der Meer T, De Jong D, Bernards R. High incidence of thymic epithelial tumors in E2F2 transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(11):10476–10483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opavsky R, Tsai SY, Guimond M, et al. Specific tumor suppressor function for E2F2 in Myc-induced T cell lymphomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(39):15400–15405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rounbehler RJ, Rogers PM, Conti CJ, Johnson DG. Inactivation of E2f1 enhances tumorigenesis in a Myc transgenic model. Cancer Res. 2002;62(11):3276–3281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rounbehler RJ, Schneider-Broussard R, Conti CJ, Johnson DG. Myc lacks E2F1’s ability to suppress skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:5341–5349. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adhikary S, Eilers M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(8):635–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):976–990. doi: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ragnarsson G, Eiriksdottir G, Johannsdottir JT, Jonasson JG, Egilsson V, Ingvarsson S. Loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 1p in different solid human tumours: association with survival. Br J Cancer. 1999;79(9-10):1468–1474. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki D, Uzawa K, Watanabe T, et al. Frequent allelic losses on the short arm of chromosome 1 and decreased expression of the p73 gene at 1p36.3 in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Int J Oncol. 2002;20(2):355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefeuvre M, Gunduz M, Nagatsuka H, et al. Fine deletion analysis of 1p36 chromosomal region in oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38(1):94–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komuro H, Valentine MB, Rowe ST, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of chromosome 1p36 deletions in human MYCN amplified neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(11):1695–1698. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, et al. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cowling VH, Cole MD. E-cadherin repression contributes to c-Myc-induced epithelial cell transformation. Oncogene. 2007;26(24):3582–3586. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravitz MJ, Chen L, Lynch M, Schmidt EV. c-myc Repression of TSC2 contributes to control of translation initiation and Myc-induced transformation. Cancer Res. 2007;67(23):11209–11217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurland JF, Tansey WP. Myc-mediated transcriptional repression by recruitment of histone deacetylase. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3624–3629. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson JD, Oster SK, Shago M, Khosravi F, Penn LZ. Identifying genes regulated in a Myc-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):36921–36930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]