Abstract

We previously showed alterations in the thymus during experimental infection with Plasmodium berghei. Such alterations comprised histological changes, with loss of cortical–medullary limits, and the intrathymic presence of parasites. As the combination of chemokines, adhesion molecules and extracellular matrix (ECM) is critical to appropriate thymocyte development, we analysed the thymic expression of ECM ligands and receptors, as well as chemokines and their respective receptors during the experimental P. berghei infection. Increased expression of ECM components was observed in thymi from infected mice. In contrast, down-regulated surface expression of fibronectin and laminin receptors was observed in thymocytes from these animals. Moreover, in thymi from infected mice there was increased CXCL12 and CXCR4, and a decreased expression of CCL25 and CCR9. An altered thymocyte migration towards ECM elements and chemokines was seen when the thymi from infected mice were analysed. Evaluation of ex vivo migration patterns of CD4/CD8-defined thymocyte subpopulations revealed that double-negative (DN), and CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive (SP) cells from P. berghei-infected mice have higher migratory responses compared with controls. Interestingly, increased numbers of DN and SP subpopulations were found in the spleens of infected mice. Overall, we show that the thymic atrophy observed in P. berghei-infected mice is accompanied by thymic microenvironmental changes that comprise altered expression of thymocyte migration-related molecules of the ECM and chemokine protein families, which in turn can alter the thymocyte migration pattern. These thymic disturbances may have consequences for the control of the immune response against this protozoan.

Keywords: chemokines, extracellular matrix, Plasmodium berghei, T-cell development, thymus

Introduction

The immune response during malaria is highly complex; this is partially the result of the intricate molecular structure of Plasmodium sp., the aetiological agent of the disease. This protozoan stimulates multifaceted immune responses, including antibodies, natural killer (NK) and NKT cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.1,2 The immune response to the intraerythrocytic stages of the parasite has been better characterized by the use of murine experimental models. In this stage the CD4+ T helper type 1 response is essential for the development of the next events of the immune response in experimental malaria.3,4

We previously reported that the thymus gland is also a target organ in Plasmodium berghei infection: there is atrophy with depletion of CD4+ CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes, and histological alterations with loss of delimitation between the cortical and medullar regions. Moreover, we detected the intrathymic presence of parasites.5

The thymus is a primary lymphoid organ, responsible for the differentiation of T lymphocytes, including the shaping of an appropriate T-cell repertoire. This process is controlled by the cells and molecules of the thymic microenvironment, a tri-dimensional network essentially formed by epithelial cells, together with small numbers of dendritic cells, macrophages and fibroblasts.6,7 Accordingly, it is conceivable that pathological changes of the thymic microenvironment, including those induced by infectious agents,8 may result in a disruption of normal intrathymic T-cell development, which may lead (among other changes) to altered export of T-cells to the periphery, as shown in experimental Chagas’ disease.9 A recent paper that measured the thymi of African children demonstrated a closer relation between mortality factor and thymus size, and children who had malaria had smaller thymi.10

Thymocyte migration seems to be controlled by the combined effects of a series of molecular interactions, including those mediated by extracellular matrix proteins, as well as by chemokines, all being produced/secreted by thymic microenvironmental cells.9,11 For example, the chemokines CXCL12 and CCL25 are relevant for inducing the migration of developing thymocytes, an effect that is mediated by the CXCR4 and CCR9 receptors, respectively.12 The extracellular matrix (ECM) ligands, fibronectin and laminin, are also very important for the migration of developing thymocytes through their interaction with specific integrin-type receptors, including VLA-4 and VLA-5 (CD49d/CD29 and CD49e/CD29) with fibronectin, and VLA-6 (CD49f/CD29) with laminin.11,13,14 Again, any changes in these interactions might lead to a disturbance in thymocyte migration. In fact, this has been demonstrated in the thymus of the non-obese diabetic mouse, which has an expression/functional defect of VLA-5.15,16 Moreover, in Trypanosoma cruzi experimental infection, the thymic atrophy, here defined by loss of thymus weight and cellularity, was characterized by premature escape of immature cells, mainly the DP subpopulation, probably as a result of hyper-responsiveness to ECM and chemokine components, and resulting in the premature and abnormal escape of DP lymphocytes and the consequent presence of immature T cells in the periphery.17,18

Following from this, changes in the expression/function of one or more of the cell-migration-related molecules discussed above may result in abnormal intrathymic T-cell development with consequences in the shaping of the peripheral T-cell pool. Herein we investigated the intrathymic expression of ECM ligands and receptors, as well as chemokines and their respective receptors, during the experimental P. berghei infection. We also evaluated thymic atrophy in this infectious disease, and its possible consequences for the T-cell migratory response.

Our data explain the significant intrathymic alterations in P. berghei-infected mice, comprising the expression of cell-migration-related ligands, including the ECM elements laminin and fibronectin, as well as the chemokines CCL25 and CXCL12. Moreover, the thymocyte migratory response to these ECM and chemokine ligands is enhanced in infected mice, suggesting that a defect in cell-migration-related thymic function may contribute to shaping the abnormal peripheral pool of T lymphocytes seen in murine malaria.

Materials and methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free 8-week-old male BALB/c mice were purchased from CEMIB/UNICAMP (Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil) and housed in microisolator cages with free access to water and food. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the State University of Campinas Committee on the Use and Care of Animals.

Infection of mice

Ten animals were infected with 5 × 106 red blood cells parasitized by P. berghei-NK65 (PbNK-65) or only injected with saline (negative control group). After 14 days of infection, control and infected mice were anaesthetized, killed and their thymi were collected and used in the experiments described below.

Cytofluorometry

Thymi were minced, washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% fetal calf serum for subsequent cellularity evaluation, which was followed by triple immunofluorescence staining. Appropriate dilutions of the following fluorochrome-labelled monoclonal antibodies were used: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/anti-CD4 (clone GK1.5), Alexa Fluor 647/anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), PeCy-7/anti-CD3 (clone 145-2C11), phycoerythrin (PE)/anti-CD49d (clone 9C10), PE/anti-CD49e (clone 5H10-27), PE/anti-CD49f (clone GOH3), PE/anti-CXCR4 (clone B11/CXCR4) and PE/anti-CCR9 (clone 242503). These reagents were purchased from Pharmingen/Becton-Dickinson (South San Francisco, CA) and R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fluorochrome-labelled isotype-matched negative controls for the specific monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen. Cells were stained for 20 min and then washed with PBS, fixed and analysed by flow cytometry in a FACsCANTO® device (Becton-Dickinson) equipped with Diva software. Analyses were performed after recording 10 000 events for each sample using FCS Express V3 software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Splenic cells from infected and control animals were also processed and analysed by flow cytometry. In this case, CD4+ and CD8+ cell populations were analysed by gating on CD3+ cells.

Immunofluorescence

Thymi were embedded in Tissue-Tek (LEICA Instruments, Nussloch, Germany) and subsequently frozen at −70°. Five-micrometre thick cryostat sections were settled on silanized glass slides, acetone-fixed and blocked with PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Samples were submitted to anti-fibronectin or anti-laminin primary antibody incubation (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 1 hr at room temperature, washed three times with PBS and labelled with FITC-coupled secondary antibody incubation (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) for an additional 30 min. Samples were analysed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus) and the images obtained were subsequently quantified for the presence of ECM proteins using the Image J software.19

Gene expression (real-time polymerase chain reaction)

The expression of chemokine genes was evaluated by real-time quantitative transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Thymus RNA was extracted from tissues using the Illustra RNAspin Mini (GE Healthcare, Amersham, UK). After RNA quantification and analysis of RNA integrity on a 1·5% agarose gel, reverse transcription was performed with approximately 2 μg of RNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The complementary DNA was quantified in Nanodrop by determining the absorbance at 260 nm, and the 260 : 280 nm absorbance ratio was calculated. The PCR was performed with an ABI Prism 7300 device (Applied Biosystems) and the reactions were carried out in a 25 μl volume and in the presence of the TaqMan PCR Master Mix™ (Applied Biosystems), using different sets of oligonucleotides and probes for the amplification of messenger RNA type II Keratin K5 (endogenous control), CXCL12 and CCL25 genes. These corresponded (respectively) to the following reference numbers (Applied Biosystems): Mm0050354_ml (kindly provided by Dr A. Morrot), Mm00446190_ml and Mm00439616_ml. Data are presented as relative messenger RNA levels calculated using the equation 2−ΔCt (where ΔCt = Ct of target gene minus Ct of K5).20

Transmigration experiments

Thymocyte migratory response was assessed as described previously.15,17 Briefly, 5-μm pore-size inserts of transwell plates (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) were coated with 10 μg/ml BSA, fibronectin, laminin (R&D Systems) or PBS for 1 hr at 37° and then blocked with PBS/0·5% BSA for 45 min at 37°. Thymocytes (2·5 × 106 in 100 μl RPMI-1640/1% BSA) were added in the upper chambers. After 3 hr of incubation at 37° in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, migration was defined by counting the cells that migrated to the lower chambers containing only migration milieu (RPMI-1640/1% BSA) or containing 400 ng/ml of the chemokines CXCL12 or CCL25 (R&D Systems). The migration medium was always devoid of fetal calf serum, hence avoiding any serum-derived migration stimuli such as fibronectin and other soluble factors. Migrating cells were ultimately counted, labelled with appropriate antibodies and analysed by flow cytometry. The results are presented in terms of total migration as well as of relative numbers (percentages of input) and correspond to specific migration after subtracting the numbers found in wells coated only with BSA.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation of the results between control and infected mice was carried out using unpaired t-test, using the graphpad prism 4·0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Results are given as mean values (± SE) and P< 0·05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Extracellular matrix ligands and receptors are modulated in thymi from P. berghei-infected mice

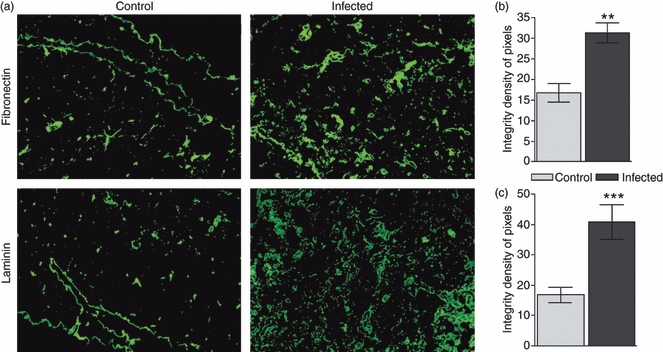

We first investigated if ECM ligands and receptors in thymi were altered in P. berghei-infected animals. As ascertained by imunohistochemistry, we detected an increase of fibronectin and laminin relative contents within the thymic lobules of infected mice, as compared with controls. This was further confirmed quantitatively by histometric computer-based analyses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Extracellular matrix density in the thymus. (a) Immunofluorescence staining shows enhancement of fibronectin-relative contents in the thymus from Plasmodium berghei-infected mice compared with the control. Enhanced density was also observed for laminin staining (original magnification, × 100). (b) and (c) The graphics correspond to quantitative analysis of selected microscopic fields of thymi from control and infected mice in terms of fibronectin and laminin, respectively. Results are expressed in pixels per square millimetre and represent the mean ± SE for at least five animals. **P < 0·01, and ***P < 0·001.

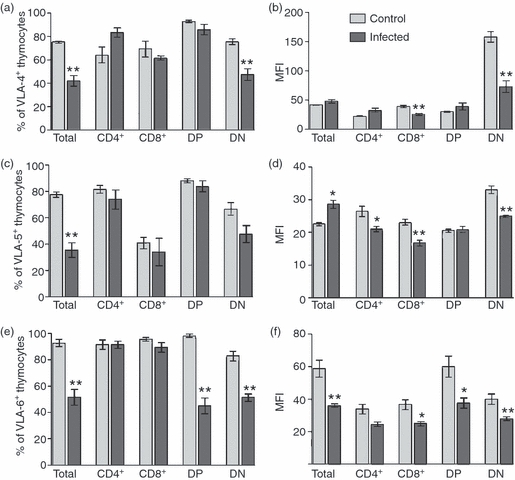

In contrast to the increase in fibronectin and laminin contents, flow cytometric evaluation of CD4- and CD8-defined thymocytes from infected mice revealed a decrease in the relative numbers and membrane density of the fibronectin receptors VLA-4 and VLA-5 (CD49d and CD49e, respectively), as well as the laminin receptor VLA-6 (CD49f). Infected mice presented a decrease in the relative numbers of VLA-4+/double negative (DN) thymocytes, and a decrease in membrane expression levels of this receptor on DN and CD8+ single-positive (SP) subpopulations (Fig. 2a,b). When we analysed VLA-5, we found that the relative numbers of cells expressing this receptor were not changed, as compared with controls. However, thymocytes from infected mice presented decrease VLA-5 density, particularly in the CD4+ and CD8+ SP subpopulations (Fig. 2c,d).

Figure 2.

Altered expression of fibronectin receptors (VLA4 and VLA5) and laminin receptor (VLA6) in total thymocytes and in CD4/CD8-defined subpopulations (DN: CD4− CD8−, DP: CD4+ CD8+, CD4: CD4+ CD8−, CD8: CD4− CD8+) from control and Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. (a), (c) and (e) Decreased percentage of thymocytes from infected mice that express VLA4, VLA5 and VLA-6, respectively. (b), (d), and (f) Decreased expression of fibronectin receptors VLA4 and VLA5, and laminin receptor VLA6 in thymocytes from infected mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SE for at least five animals. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01.

Both, DN and DP thymocyte subsets from P. berghei-infected mice exhibited a decrease in the relative numbers of VLA-6+ cells, as compared with control animals. Membrane expression levels were also altered because DN, DP and CD8+ SP thymocytes showed a decreased density of VLA-6, as evaluated by the mean of fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2e,f).

Overall, these data indicate that cell migration-related ECM integrin-type receptors are down-regulated in thymocyte subpopulations from P. berghei-infected mice.

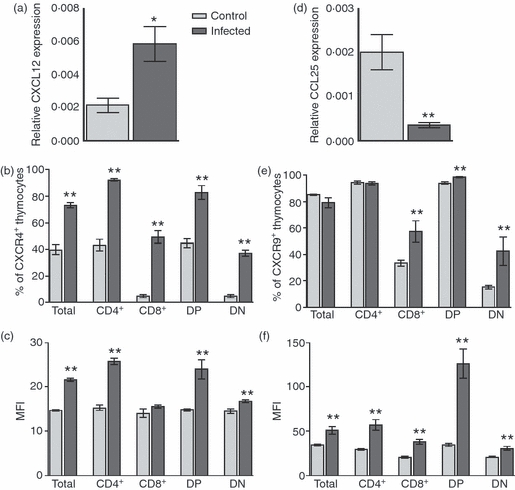

The expression patterns of chemokines and their receptors are changed in thymocytes from P. berghei-infected mice

We also evaluated two selected chemokines produced by the thymic microenvironment, CCL25 and CXCL12, as well as their corresponding receptors, CCR9 and CXCR4, expressed in thymocyte subsets. At 14 days post-infection, the thymi from P. berghei-infected mice showed a statistically significant increase in CXCL12 expression when compared with control thymi, as ascertained by quantitative PCR (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

Altered expression of chemokines CCL12 and CCL25, and their receptors (CXCR4 and CCR9, respectively) in total thymocytes and in CD4/CD8-defined subpopulations (DN: CD4− CD8−, DP: CD4+ CD8+, CD4: CD4+ CD8−, CD8: CD4− CD8+) from control and Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. (a) and (d) Relative gene expression of CXCL12 and CCL25, respectively, in control and P. berghei-infected mice. (b) and (e) Increased percentage of thymocytes from control and P. berghei-infected mice expressing the chemokine receptors, CXCR4 and CCR9. (c) and (f) Increased CXCR4 and CCR9 fluorescence intensity in thymocytes from control and infected mice. Results are expressed as mean ± SE for at least five animals. *P < 0·05, and **P < 0·001.

Concomitantly with such increased CXCL12 relative gene expression, all thymocyte subpopulations from infected mice exhibited an increase in the relative numbers of cells expressing CXCR4 (Fig. 3b). Membrane expression levels were also higher in thymocytes from infected mice (except in CD8+ SP thymocytes), when compared with controls (Fig. 3c).

In contrast, the analysis of CCL25 relative gene expression in the thymi from P. berghei-infected mice revealed decreased levels of mesenger RNA, when compared with controls (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the relative numbers of thymocytes expressing CCR9 were decreased in DN and CD8+ SP subsets, and increased in DP thymocytes (Fig. 3e). Nevertheless, membrane density of CCR9 was higher in all thymocyte subpopulations from infected mice, when compared with control mice (Fig. 3f).

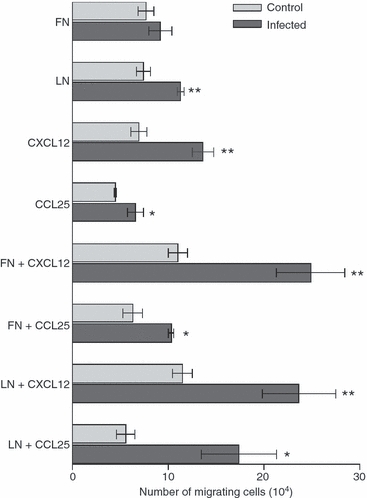

Chemokine/ECM-driven thymocyte migration is modified following P. berghei infection

To investigate a possible functional impact on thymocytes triggered by interactions mediated by selected ECM and chemokines, we analysed the migratory response through fibronectin or laminin, or towards CXCL12 or CCL25, as well as the combined effect of each chemokine with one given ECM element. Overall, when we evaluated the bulk of migrating thymocytes, we found an enhanced higher migratory response of thymocytes from infected mice compared with controls (Fig. 4). This was seen in respect to laminin, CXCL12 and CCL25 applied alone, as well as to the combined stimuli of laminin with a given chemokine. The only exception was seen when fibronectin was applied alone: in this case the migration pattern was similar in both control and infected groups. Nevertheless, thymocytes from infected mice migrated significantly more than the control ones when fibronectin was combined with CXCL12 or CCL25. In fact, these chemokines alone were able to enhance the migratory response of thymocytes from P. berghei-infected mice, when compared with controls.

Figure 4.

Altered thymocyte migration in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. The graphic shows the numbers of total cells migrating towards fibronectin (FN) and laminin (LN), or CXCL12 and CCL25, as well as the chemokines combined with one given extracellular matrix (ECM) element. Results are expressed as mean ± SE derived from five experiments, each one obtained by a pool of at least five control and 10 infected mice. *P < 0·05 and **P < 0·01.

We next evaluated the migratory responses of each CD4/CD8-defined thymocyte subset, under the same stimuli. We found that DN cells and CD4+ and CD8+ SP cells from P. berghei-infected mice showed higher migratory activity than controls (see data in Table 1). Rather surprisingly, the number of CD4+ CD8+ living migrating cells was consistently decreased when they derived from infected animals compared with controls.

Table 1.

Altered ex vivo migratory responses of CD4/CD8-defined thymocyte subpopulations from Plasmodium berghei-infected mice1,2

| Stimuli | Group | DN | DP | CD4+ | CD4+ fold change | CD8+ | CD8+ fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fibronectin | Control | 0·72 ± 0·05 | 4·1 ± 0·12 | 2·01 ± 0·25 | 2·5 | 0·65 ± 0·15 | 4·3 |

| Infected | 1·32 ± 0·24 | 1·0 ± 0·04** | 5·04 ± 0·76* | 2·83 ± 0·44* | |||

| Laminin | Control | 0·58 ± 0·16 | 3·79 ± 0·66 | 1·71 ± 0·20 | 3·4 | 0·70 ± 0·11 | 2·4 |

| Infected | 1·56 ± 0·34 | 1·13 ± 0·06* | 5·86 ± 0·32* | 1·71 ± 0·20** | |||

| CXCL12 | Control | 0·21 ± 0·01 | 4·35 ± 0·80 | 0·90 ± 0·31 | 7·7 | 0·44 ± 0·06 | 9·1 |

| Infected | 1·50 ± 0·20** | 1·04 ± 0·16* | 6·96 ± 0·88** | 4·03 ± 0·43** | |||

| CCL25 | Control | 0·11 ± 0·02 | 2·72 ± 0·42 | 0·55 ± 0·18 | 6·6 | 0·26 ± 0·06 | 7·9 |

| Infected | 0·90 ± 0·17** | 0·73 ± 0·09* | 3·68 ± 0·36** | 2·06 ± 0·26** | |||

| Fibronectin + CXCL12 | Control | 0·32 ± 0·09 | 5·50 ± 1·33 | 1·06 ± 0·32 | 12·9 | 0·49 ± 0·17 | 13·8 |

| Infected | 2·35 ± 0·44** | 2·04 ± 0·37* | 13·68 ± 2·13** | 6·79 ± 0·85** | |||

| Fibronectin + CCL25 | Control | 0·22 ± 0·06 | 3·43 ± 0·73 | 0·73 ± 0·14 | 7·4 | 0·24 ± 0·07 | 11·3 |

| Infected | 1·21 ± 0·17* | 0·93 ± 0·03** | 5·45 ± 0·32** | 2·73 ± 0·16** | |||

| Laminin + CXCL12 | Control | 0·32 ± 0·31 | 4·89 ± 0·46 | 1·64 ± 0·35 | 8·5 | 0·84 ± 0·18 | 10·2 |

| Infected | 2·48 ± 0·47** | 2·06 ± 0·16* | 14·06 ± 0·99** | 8·61 ± 0·85** | |||

| Laminins + CCL25 | Control | 0·11 ± 0·02 | 2·90 ± 0·39 | 0·57 ± 0·15 | 15·6 | 0·22 ± 0·07 | 23·2 |

| Infected | 1·88 ± 0·44** | 1·57 ± 0·27* | 8·91 ± 1·75** | 5·11 ± 1·52** |

DN, double-negative; DP, double-positive.

Only living cells (ascertained by the Trypan blue exclusion test) were counted after migration.

The relative numbers (percentage of input) of migrating thymocytes towards different haptotatic stimuli are representative of three similar experiments, each one corresponding to a pool of four control and six infected animals. *P <0·05, and **P <0·01.

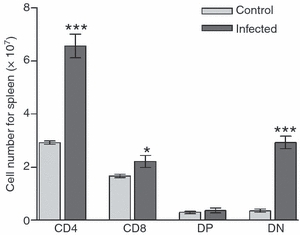

Last, and considering that migratory responses of thymocytes from infected mice were significantly higher than the corresponding controls, we evaluated the T-cell pool in the periphery, more specifically in the spleen. As depicted in Fig. 5, the numbers of immature thymocytes (DN subpopulation) were significantly increased in infected animals, as well as the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ SP T-cell subsets.

Figure 5.

Absolute cell number of different T-cell subsets in spleens from control and Plasmocium berghei-infected mice. Increased numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive (SP) subpopulation, and CD4− CD8− cells (double-negative; DN) can be observed in infected animals. Results are expressed as mean ± SE for at least five animals. *P < 0·05, and ***P < 0·001.

Discussion

The interplay between thymoctes and the thymic microenvironment is modulated by a variety of proteins, like ECM components and chemokines, and it has been considered of crucial importance to provide the correct signals to thymocyte migration and maturation.14,21 In this sense, it is reasonable to suppose that alterations in ECM elements and chemokines are implicated in thymic dysfunction.

We have previously reported that P. berghei infection induces thymic atrophy with changes in its architecture that are characterized by loss of the cortico–medullary delimitation and massive depletion of thymocytes, mainly the DP subpopulation.5 In this paper we have described how thymic atrophy induced by malaria infection is also characterized by profound alterations in the expression of ECM components and chemokines, in such a way that thymocyte migration inside the thymus, which is an essential event for T-cell development, is severely compromised.

The intrathymic contents of selected chemokines, CXCL12 and CCL25, as well as of the ECM proteins fibronectin and laminin, were altered in thymi from infected animals compared with uninfected controls. These changes are similar to those described during acute murine infection by T. cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas’ disease.17,18 At least in relation to fibronectin, it is possible that the intrathymic contents in the remaining cortex of the thymic lobules may be related to the DP thymocyte death because this ECM protein was reported as being able to increase the incidence of death in these thymocyte subsets.22 Nevertheless a cause–effect relationship remains to be determined.

In any case, the increase of fibronectin, laminin and CXCL12 and the decrease of CCL25 strongly indicate anomalies in thymocyte migration, as it had been found in T. cruzi-infected mice. We therefore defined the patterns of membrane expression of corresponding receptors, comparing normal with P. berghei-infected mice. However, differing from the patterns seen during experimental Chagas’ disease, plasmodial infection resulted in a decrease of the fibronectin receptors, VLA-4 and VLA-5, as well as of the laminin receptor VLA-6. Overall, the expression of these receptors was not only decreased in total thymocytes, but also in CD4/CD8-defined subsets. In contrast, the membrane expression of the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CCR9 was increased in P. berghei-infected animals, comprising both immature and mature thymocyte subsets.

The chemokine CXCL12 is required by thymocytes to migrate from the cortico–medullary junction to the subcapsular zone, where specific signals from intrathymic microenvironmental niches induce and regulate the earliest stages of thymocyte development.14,23,24 It has also been demonstrated that an enhanced fibronectin expression favours the chemokine sequestration preventing its degradation by matrix metalloproteinases.25 We have found that alterations in the ECM pattern were accompanied by increased expression of the chemokine CXCL12 and its respective receptor, the CXCR4 molecule. At the DP stage, thymocytes start to express the CCR9 molecule in response to CCL25 and then migrate towards the medulla. It has been proposed that the CCL25/CCR9 interaction is necessary to prevent apoptosis during thymocyte development.26 As CCL25 is dramatically decreased in the experimental model presented here, it is reasonable to suppose that DP thymocytes are being missed by apoptosis. This question is under investigation in our laboratory.

The mechanisms leading to severe thymic atrophy with changes in the expression of ECM elements and chemokines and their respective receptors in P. berghei-infected animals are not understood. We believe that the presence of Plasmodium inside the thymus, as reported earlier by our group, is important, and most probably sufficient, to evoke alterations in the thymic microenvironment.5 In fact, we already have strong evidence of the contribution of the leptin hormone and transforming growth factor-β, both thymus-stimulating molecules, for the thymic atrophy during malaria infection. Although it remains to be defined whether there is an intrathymic production of leptin, preliminary data indicate a constitutive expression of this molecule by the human thymic epithelium (W. Savino, personal communication). Experiments from our laboratory have shown that the thymi of infected animals present a considerably decreased expression of leptin and transforming growth factor-β and this may be one of the mechanisms leading to severe atrophy observed during this infection (P. R. A. Nagib, J. Gameiro, L. G. Stivanin-Siva, M. S. P. Arruda, D. M. S. Villa-Verde, W. Savino & L. Verinaud, manuscript in preparation).

However, the possibility that systemic factors, like cytokines, glucocorticoids and/or other hormones, released during the immune response against the parasite, are also inducing alterations in the thymus cannot be abandoned.

Taken together, these results form a complex scenario with increased bioavailability of cell-migration-related ligands, namely chemokines and ECM glycoproteins, together with up-regulation or down-regulation of the corresponding receptors. It was therefore important to know whether the degree of migratory response triggered ex vivo by fixed amounts of these ligands would also be altered. When total thymocyte migration was evaluated, all ligands except for fibronectin induced higher migratory responses in thymocytes from infected animals than in controls. As ECM and chemokines were defined to exhibit a combined effect in normal thymocyte migration,11,14 we also tested these molecules, applied together in the transwell chambers. In these conditions, the migration of thymocytes from infected mice was statistically higher in response to the combined stimuli of each ECM protein (laminin or fibronectin) to each chemokine (CXCL12 and CCL25). Further analysis of CD4/CD8-defined thymocyte subsets revealed that such higher migratory responses were seen in both immature and mature subpopulations (DN, CD4+ and CD8+).

The study of recent thymic emigrants would provide valuable information and would contribute to explaining the results presented here. However, the severe atrophy observed during acute P. berghei infection generates a technical problem because injecting FITC into this atrophic thymus is virtually impossible. We suppose that CD4– and CD8– cells found in the spleens of P. berghei-infected mice may be recently thymus-derived, but this hypothesis remains to be demonstrated because γδ T cells and a subset of NKT cells are also CD4– and CD8–. Although little information is available regarding the function and regulation of these cells during chronic malaria, there is accumulating evidence about the participation of T-cell receptor γδ T cells and NKT cells in the immune response to Plasmodium infection.27–30 So, much more work is needed to further investigate peripheral proliferating DN cells in our experimental model. The enhancement of CD4+ and CD8+ SP lymphocytes may be evidently attributed to the proliferation of these subpopulations in response to the parasite. In T. cruzi infection, for example, alterations in thymocyte migration are also observed and high numbers of DP thymocytes are found in the lymph nodes.9 These authors suggest that these immature lymphocytes in the periphery can play an important role in the autoimmunity process observed during Chagas’ disease.31 Although Plasmodium infection does not present autoimmune complications, it is possible that the alterations observed in the migratory activity of thymocytes and the presence of the DN subpopulation in the spleen of mice during infection can also affect the immune response against the parasite. It has been demonstrated that some DN T-cell subpopulations in the periphery can have a regulatory activity on other cells of the immune system.32,33

Overall, we provide evidence that the thymic atrophy observed in P. berghei-infected mice is characterized by severe thymic microenvironment alterations, which can alter the thymic function reflected mainly by changes in the thymocyte migration pattern. It remains to be investigated whether these disturbances in the thymus compartment can have consequences for the immune response against this protozoan.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Ana Leda Longhini from Centro Integrado de Pesquisas Onco-hematológicas na Infância (CIPOI/UNICAMP). This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), grant number #04/03599-1. P.R.A.N. was a recipient of a doctoral fellowship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq #14229/2005-1) and State University of Campinas (UNICAMP). F.T.M.C. and W.S. are recipients of a research scholarship from CNPq.

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Marsh K, Kinyanjui S. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Parasite Immunol. 2006;28:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2006.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schofield L, Grau GE. Immunological processes in malaria pathogenesis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:722–35. doi: 10.1038/nri1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seixas E, Ostler D. Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi (AS): differential cellular responses to infection in resistant and susceptible mice. Exp Parasitol. 2005;110:394–405. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fonseca L, Seixas E, Butcher G, Langhorne J. Cytokine responses of CD4+ T cells during a Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi (ER) blood-stage infection in mice initiated by the natural route of infection. Malar J. 2007;6:77–86. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-6-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade CF, Gameiro J, Nagib PR, et al. Thymic alterations in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Cell Immunol. 2008;253:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savino W, Dardenne M. Neuroendocrine control of thymus physiology. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:412–43. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.4.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciofani M, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. The thymus as an inductive site for T lymphopoiesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:463–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savino W. The thymus is a common target organ in infectious diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:472–83. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes-da-Cruz DA, de Meis J, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Savino W. Experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection alters the shaping of the central and peripheral T-cell repertoire. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:825–32. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00156-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garly ML, Trautner SL, Marx C, et al. Thymus size at 6 months of age and subsequent child mortality. J Pediatr. 2008;153:683–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savino W, Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Silva JS, Dardenne M, Cotta-de-Almeida V. Intrathymic T-cell migration: a combinatorial interplay of extracellular matrix and chemokines? Trends Immunol. 2002;23:305–13. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu W, Chen W. Roles of chemokines in thymopoiesis: redundancy and regulation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:266–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savino W, Villa-Verde DM, Lannes-Vieira J. Extracellular matrix proteins in intrathymic T-cell migration and differentiation? Immunol Today. 1993;14:158–61. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90278-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savino W, Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Smaniotto S, Silva-Monteiro E, Villa-Verde DM. Molecular mechanisms governing thymocyte migration: combined role of chemokines and extracellular matrix. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:951–61. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1003455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotta-de-Almeida V, Villa-Verde DM, Lepault F, Pleau JM, Dardenne M, Savino W. Impaired migration of NOD mouse thymocytes: a fibronectin receptor-related defect. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1578–87. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Smaniotto S, Keller AC, Dardenne M, Savino W. Multivectorial abnormal cell migration in the NOD mouse thymus. J Immunol. 2008;180:4639–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotta-de-Almeida V, Bonomo A, Mendes-da-Cruz DA, et al. Trypanosoma cruzi infection modulates intrathymic contents of extracellular matrix ligands and receptors and alters thymocyte migration. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2439–48. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendes-da-Cruz DA, Silva JS, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Savino W. Altered thymocyte migration during experimental acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection: combined role of fibronectin and the chemokines CXCL12 and CCL4. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:1486–93. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins TJ. ImageJ for microscopy. BioTechniques. 2007;43:25–30. doi: 10.2144/000112517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Overbergh L, Giulietti A, Valckx D, et al. The use of real-time reverse transcriptase PCR for the quantification of cytokine gene expression. J Biomol Tech. 2003;14:33–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Zoned out: functional mapping of stromal signaling microenvironments in the thymus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:649–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takayama E, Kina T, Katsura Y, Tadakuma T. Enhancement of activation-induced cell death by fibronectin in murine CD4+ CD8+ thymocytes. Immunology. 1998;95:553–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plotkin J, Prockop SE, Lepique A, Petrie HT. Critical role for CXCR4 signaling in progenitor localization and T cell differentiation in the postnatal thymus. J Immunol. 2003;171:4521–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez-Lopez C, Varas A, Sacedon R, Jimenez E, Munoz JJ, Zapata AG, Vicente A. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for early human T-cell development. Blood. 2002;99:546–54. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pelletier AJ, van der Laan LJ, Hildbrand P, Siani MA, Thompson DA, Dawson PE, Torbett BE, Salomon DR. Presentation of chemokine SDF-1 alpha by fibronectin mediates directed migration of T cells. Blood. 2000;96:2682–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Youn BS, Yu KY, Oh J, Lee J, Lee TH, Broxmeyer HE. Role of the CC chemokine receptor 9/TECK interaction in apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2002;7:271–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1015320321511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen DS, Siomos MA, Buckingham L, Scalzo AA, Schofield L. Regulation of murine cerebral malaria pathogenesis by CD1d-restricted NKT cells and the natural killer complex. Immunity. 2003;18:391–402. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soulard V, Roland J, Sellier C, et al. Primary infection of C57BL/6 mice with Plasmodium yoelii induces a heterogeneous response of NKT cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75:2511–22. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01818-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho M, Tongtawe P, Kriangkum J, et al. Polyclonal expansion of peripheral γδ T cells in human Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Infect Immun. 1994;62:855–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.855-862.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farouk SE, Mincheva-Nilsson L, Krensky AM, Dieli F, Troye-Blomberg M. γδT cells inhibit in vitro growth of the asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum by a granule exocytosis-dependent cytotoxic pathway that requires granulysin. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2248–56. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kierszenbaum F. Chagas’ disease and the autoimmunity hypothesis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:210–23. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomson CW, Lee BPL, Zhang L. Double negative regulatory T cells. Immunol Res. 2006;34:163–7. doi: 10.1385/IR:35:1:163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang D, Yang W, Degauque N, Tian Y, Mikita A, Zheng XX. New differentiation pathway for double negative regulatory T cells that regulates the magnitude of immune responses. Blood. 2007;109:4071–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-050625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]