Abstract

Problem

The expiry of medicines in the supply chain is a serious threat to the already constrained access to medicines in developing countries.

Approach

We investigated the extent of, and the main contributing factors to, expiry of medicines in medicine supply outlets in Kampala and Entebbe, Uganda. A cross-sectional survey of six public and 32 private medicine outlets was done using semi-structured questionnaires.

Local setting

The study area has 19 public medicine outlets (three non-profit wholesalers, 16 hospital stores/pharmacies), 123 private wholesale pharmacies and 173 retail pharmacies, equivalent to about 70% of the country’s pharmaceutical businesses. Our findings indicate that medicines prone to expiry include those used for vertical programmes, donated medicines and those with a slow turnover.

Relevant changes

Awareness about the threat of expiry of medicines to the delivery of health services has increased. We have adapted training modules to emphasize management of medicine expiry for pharmacy students, pharmacists and other persons handling medicines. Our work has also generated more research interest on medicine expiry in Uganda.

Lessons learned

Even essential medicines expire in the supply chain in Uganda. Sound coordination is needed between public medicine wholesalers and their clients to harmonize procurement and consumption as well as with vertical programmes to prevent duplicate procurement. Additionally, national medicine regulatory authorities should enforce existing international guidelines to prevent dumping of donated medicine. Medicine selection and quantification should be matched with consumer tastes and prescribing habits. Lean supply and stock rotation should be considered.

Résumé

Problématique

Le dépassement de la date de péremption des médicaments dans la chaîne d'approvisionnement compromet gravement l'accès déjà restreint aux médicaments dans les pays en développement.

Démarche

Nous avons étudié l'ampleur du problème posé par le dépassement de la date de péremption des médicaments dans les points d'approvisionnement à Kampala et à Entebbe, en Ouganda, et les principaux facteurs qui y contribuent. Une enquête transversale portant sur six points de vente publics et 32 points de ventes privés de médicaments a été réalisée en utilisant des questionnaires semi-structurés.

Contexte local

L'étude couvrait 19 points de vente publics (trois grossistes à but non lucratif, 16 magasins/pharmacies d'hôpitaux), 123 grossistes en pharmacie privés et 173 pharmacies de détail, représentant au total environ 70 % de l'activité pharmaceutique du pays. Nos résultats indiquent que parmi les médicaments ayant tendance à être plus souvent périmés, figurent ceux utilisés pour les programmes verticaux, ceux provenant de dons et ceux dont le débit de vente est faible.

Modifications pertinentes

On assiste à une prise de conscience grandissante de la menace que constitue, pour la prestation de services de santé, la péremption des médicaments. Nous avons adapté des modules de formation mettant l'accent sur la gestion du risque de péremption des médicaments, destinés aux étudiants en pharmacie, aux pharmaciens et à d'autres personnes chargées de gérer des médicaments. Notre travail a eu pour conséquence également d'accroître l'intérêt des chercheurs pour la péremption des médicaments en Ouganda.

Enseignements tirés

Même les médicaments essentiels dépassent leur date de péremption dans les chaînes d'approvisionnement en médicaments ougandaises. Il faudrait une coordination solide entre les grossistes en pharmacie du secteur public et leurs clients pour harmoniser les achats et la consommation, et entre ces grossistes et les programmes verticaux pour éviter de dupliquer certains achats. En outre, les autorités nationales de réglementation dans le domaine pharmaceutique doivent faire appliquer les recommandations internationales existantes en vue de prévenir la mise en décharge des médicaments provenant de dons. Il faut sélectionner les médicaments et les quantités correspondantes en fonction des goûts des consommateurs et des habitudes de prescription. Il convient de prendre en compte les baisses d'approvisionnement et la rotation des stocks.

Resumen

Problema

La caducidad de los medicamentos en las cadenas de suministro constituye una seria amenaza para el ya limitado acceso a los medicamentos en los países en desarrollo.

Enfoque

Investigamos la naturaleza de los factores que más contribuyen a la caducidad de los medicamentos en los puntos de distribución de medicamentos de Kampala y Entebbe, Uganda, así como la dimensión de ese problema. Para ello, se realizó una encuesta transversal en seis puntos de distribución públicos y 32 privados, utilizando cuestionarios semiestructurados.

Contexto local

En la zona estudiada había 19 puntos de distribución públicos (tres mayoristas sin fines de lucro, y 16 farmacias y almacenes de hospital), 123 farmacias mayoristas privadas y 173 farmacias minoristas, que representaban aproximadamente un 70% de las transacciones farmacéuticas en el país. Nuestros resultados muestran que entre los medicamentos con más tendencia a la caducidad figuraban los utilizados para los programas verticales, los medicamentos donados y los de baja rotación.

Cambios destacables

Se ha conseguido una mayor sensibilización sobre la amenaza que para la prestación de servicios de salud representa la caducidad de los fármacos. Hemos adaptado diversos módulos de capacitación para hacer más hincapié en la caducidad de los medicamentos entre los estudiantes de farmacia, los farmacéuticos y otras personas que manejan medicamentos. Nuestro trabajo ha generado además un mayor interés por investigar el problema de la caducidad de los medicamentos en Uganda.

Enseñanzas extraídas

En la cadena de distribución de Uganda los problemas de caducidad afectan incluso a los medicamentos esenciales. Es preciso que haya una coordinación sólida entre los mayoristas de medicamentos del sector público y sus clientes a fin de armonizar la adquisición y el consumo, así como con los programas verticales, para evitar duplicaciones de las compras. Además, las autoridades nacionales de regulación de los medicamentos deben hacer cumplir las directrices internacionales existentes para evitar el dumping de los medicamentos donados. La selección y la determinación de la cantidad de medicamentos deben corresponderse con las preferencias de los consumidores y los hábitos de prescripción, y deben tenerse en cuenta las opciones de aligeramiento de los suministros y rotación de las existencias.

ملخص

المشكلة

يُعد انتهاء صلاحية الأدوية في سلسلة إمدادات الأدوية مشكلة خطيرة بالنسبة للحصول على الأدوية والتي هي محدودة أصلاً في البلدان النامية.

الأسلوب

تقصى الباحثون المدى، والعوامل التي تساهم في انتهاء صلاحية الأدوية في منافذ إمدادات الأدوية في مدينتي كامبالا وعنتيبي في أوغندا. وأُجرى مسح مقطعي لست منافذ عامة و 32 منفذاً خاصاً للأدوية باستخدام استبيان شبه منهجي.

الوضع المحلي

وُجد في المنطقة التي أجريت فيها الدراسة 19 منفذاً عاماً للأدوية (ثلاثة منافذ للتوزيع بالجملة وهي غير ربحية، و 16 مستودعاً أو صيدلية في المستشفيات)، و 123 صيدلية خاصة للتوزيع بالجملة، و 173 صيدلية للتجزئة، وهذا يعادل حوالي 70% من حجم أعمال الصيدلة في أوغندا. وتشير النتائج التي توصل إليها الباحثون إلى أن الأدوية المعرضة لانتهاء الصلاحية تضمنت الأدوية المستخدمة في البرامج الرأسية، والأدوية الممنوحة، وتلك التي يكون دورانها بطيئاً.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

ازداد الوعي بالتهديد الناجم عن انتهاء صلاحية الأدوية المستخدمة في الخدمات الصحية. وأعد الباحثون نماذج تدريبية للتأكيد على كيفية التعامل مع انتهاء صلاحية الأدوية لطلبة الصيدلة، والصيادلة، وسائر الأشخاص المتعاملين مع الأدوية. وأدى ما قام به الباحثون إلى زيادة الاهتمام البحثي بمشكلة انتهاء صلاحية الأدوية في أوغندا.

الدروس المستفادة

حتى الأدوية الأساسية تتعرض لانتهاء الصلاحية في سلسلة إمدادات الأدوية في أوغندا. وهناك حاجة للتنسيق السليم بين المنافذ العامة لتوزيع الأدوية بالجملة والمتعاملين معها للتوفيق بين شراء الأدوية واستهلاكها، وكذلك التنسيق مع البرامج الرأسية لمنع تكرار عملية الشراء. وبالإضافة إلى ذلك، يجب على السلطات الوطنية المعنية بتنظيم الأدوية تعزيز الدلائل الإرشادية الدولية الموجودة لمنع التخلص من الأدوية الممنوحة. ويجب أن يتوافق اختيار الأدوية وكمياتها مع متطلبات المستهلكين وعادات وصف الأدوية. ويجب مراعاة التخفيف من كمية الإمدادات وتدوير المخزون من الأدوية.

Introduction

In developing countries, where budgets for medicines are often tight, the supply cycle needs to be well-managed to prevent all types of wastage, including pilferage, misuse and expiry. This wastage reduces the quantity of medicines available to patients and therefore the quality of health care they receive. At least US$550 000 worth of antiretrovirals and 10 million antimalarial doses recently expired in Uganda’s National Medical Stores (NMS).1,2

The Ugandan pharmaceutical supply system comprises three non-profit wholesalers (one government medical store and two private non-profit ventures) and several private for-profit wholesale pharmacies that supply medicines in bulk to retail units (private retail pharmacies, hospital pharmacies and drug shops). Drug shops are the smallest retail medicine outlets, are supervised by non-pharmacist health-care professionals, and are limited to handling small amounts of over-the-counter medicines.3

The expiry of medicines highlights a problem with the supply chain, which includes medicine selection, quantification, procurement, storage, distribution and use.4–6 We need to find out the factors contributing to expiry at each stage of the supply cycle in order to design pragmatic strategies to reduce the problem. The main aim of this study was to find out whether medicine expiry extends beyond public medicine outlets to the private for-profit sector, to assess the factors that contribute to or cause expiry and find out which medicines are particularly prone to expiry in the supply chain in Uganda.

Local setting and methods

A cross-sectional survey of medicine outlets within Kampala city and Entebbe municipality was used to investigate the extent of expiry of medicines and the contributing factors in Uganda. This study area contains about 70% of all pharmaceutical businesses in Uganda including 19 public outlets (three non-profit wholesalers and 16 hospital pharmacies), 123 private wholesale pharmacies and 173 retail pharmacies.7 We aimed to sample 60 medicine outlets, a figure determined using the Leslie Kish formula based on a margin of error of 10% and expiry rate of 21% of medicines.8 Non-profit wholesalers were universally sampled, with the remaining complement proportionately stratified into three hospital pharmacies, 22 private wholesales and 32 retail pharmacies. Hospital pharmacies were selected based on acceptance to participate in the study while private pharmacies were randomly chosen. We only investigated large medicine outlets (non-profit wholesalers and private wholesale pharmacies) and medium-sized outlets (retail and hospital pharmacies) and excluded drug shops because of the small range and amounts of medicines they are allowed to stock under Uganda’s National Drug Policy. Only 38 outlets including six public outlets (one governmental store, two nongovernmental non-profit wholesalers and three hospital pharmacies) and 32 private pharmacies (nine wholesale, 23 retail) consented, equivalent to a 63.3% response rate.

We developed semi-structured questionnaires, which were then administered by an interviewer to a respondent who was familiar with each outlet’s medicine supply system (predominantly pharmacists, supplies/stores officers and managers). Closed questions on expiry-related actions (medicine disposal, return by customers, exchange with supplier and price reduction/donation), and an expansion of the World Health Organization’s list of medicines recommended for assessing level II pharmaceutical indicators (antiretrovirals and some slow-moving but vital medicines added)8,9 were used to assess the incidence of expiry of medicines. We also included closed questions on the characteristics of medicines that commonly expire as this may help to develop solutions for selection and inventory management. These questions included aspects on medicine shelf life, cost, taste, donations, those that treat rare diseases, and medicines affected by changes in treatment policy. Weaknesses in medicine quantification, procurement and use were probed by 13 closed questions and those in inventory management by nine closed and two open-ended questions on personnel understanding of the two stock flow approaches of FIFO (first in first out) and FEFO (first expiry first out). The questionnaire was critiqued by three pharmacists with expertise and experience in research at Makerere University, and revised accordingly before field work. Questionnaires were administered by three of the authors and a research assistant. All data were entered into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States of America) and Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using descriptive statistics. The study proposal was reviewed and approved by the Pharmacy Department Research/Examinations Committee at Makerere University. All investigations were limited to events in the year preceding date of interview.

Expiry remains neglected

Expiry of medicines in the supply chain is a serious threat to the already constrained access to medicines in developing countries. In Uganda, volumes of valuable medicines have expired at the National Medical Stores, in district and hospital stores,1,2,10 and the problem has also been reported in Botswana, India and the United Republic of Tanzania.11,12 Through asking questions on expiry-related actions to explore the scope of the problem, we found that in five public outlets, four had disposed of (destroyed) medicines, two had exchanged medicines with their supplier, customers returned medicines in one outlet and all had received medicines at reduced prices or as donations in the previous year, due to actual or projected expiry. Similarly, of 32 private pharmacies, 18 had disposed of medicines, 14 had exchanged medicines with the supplier, customers had returned medicines in nine outlets and 24 had received medicines at reduced prices or as donations. Expiry of medicines therefore appears to be a universal problem in all medicine supply outlets.

Contributing factors

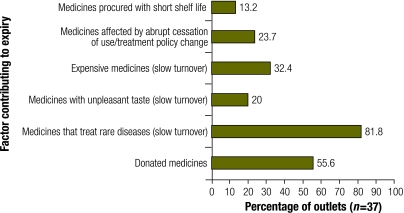

Expiry of medicines in supply facilities was common among medicines for vertical health programmes (with percentage of outlets reporting expiry) including vitamin A capsules, antiretroviral medicines, antituberculosis agents, chloroquine, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine and nystatin tablets, though expiry of medicines such as anticancer agents, tetracycline eye ointment and mebendazole was also common. Note that the number of respondents varied because not all medicines are stocked by all units. Surprisingly, all these top-expiring medicines are either essential (with a high turnover because they are used by the majority of the population) or vital (without them, the patient would die).3 A possible explanation for the expiry of anticancer drugs is slow turnover because they treat rare diseases and are expensive. Similarly, tetracycline eye ointment and mebendazole have plenty of better substitutes, which may explain their slow turnover. We corroborated some of these findings with the respondents’ perceived features of medicines that commonly expire in their stores (Fig. 1). Poor management of a change in treatment policy was implicated in the expiry of huge stocks of chloroquine, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine and isoniazid.2

Fig. 1.

Perceived characteristics of medicines that expire

On probing for contributing factors in the supply chain, the main ones included neglect of stock monitoring, lack of knowledge of basic expiry prevention tools, nonparticipation of clinicians in medicine quantification in hospitals, profit- and incentive-biased quantification, third party procurement by vertical programmes and overstocking. A few less common contributing factors were also reported (Table 1).

Table 1. Perceived factors contributing to expiry of medicines at key stages of the supply chain.

| Contributing factor | Type of medicine outleta | No. | Public | Private | Total (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum shelf life not specified in orders | P | 38 | 0 | 9 | 23.7 |

| Profit margin determines size of purchase | Q | 32 | N/A | 22 | 68.8 |

| Procurement done irrespective of present stock | Q | 35 | 1 | 0 | 2.9 |

| Medicines dumped by manufacturers | P | 32 | N/A | 6 | 18.8 |

| No advice from expert clinicians on medicines forecasts | Q | 3 | 3 | N/A | 100 |

| Standard treatment guidelines violated in forecasts | Q | 3 | 1 | N/A | 33.3 |

| Irrational prescribing causes underuse of certain medicines | U | 3 | 1 | N/A | 33.3 |

| Donations received irrespective of need | P | 5 | 1 | N/A | 20 |

| No accurate data available to facilitate quantification | Q | 28 | 2 | 0 | 7.1 |

| Obsolete medicines are sometimes procured | P | 33 | 0 | 7 | 21.2 |

| Some medicines are quantified by vertical programmes | Q | 5 | 2 | N/A | 40 |

| Seller’s incentives influence quantification | Q | 36 | 0 | 10 | 27.7 |

| Overstocking is common | Q | 37 | 0 | 12 | 32.4 |

| Use neither FIFO nor FEFO in stock management | IM | 38 | 0 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Not knowledgeable about FEFO IM | IM | 38 | 2 | 13 | 38 |

| Not knowledgeable about FIFO IM | IM | 38 | 0 | 8 | 21.1 |

| Expired medicines not isolated into secure areas | IM | 37 | 0 | 2 | 5.4 |

| No timetable for regular inventory level analysis | IM | 37 | 2 | 9 | 29.7 |

| Filing and records are poorly maintained | IM | 38 | 0 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Inventory levels not regularly monitored | IM | 37 | 4 | 24 | 75.7 |

| No specific personnel for inventory management | IM | 38 | 0 | 7 | 18.4 |

FEFO, first expiry first out; FIFO, first in first out; IM, inventory management; N/A, not applicable to that category of medicine outlet; P, procurement; Q, quantification; U, use. a Some contributing factors are specific to a type of medicine outlet. b Overall proportion of medicine outlets with that contributing factor.

Prevention of expiry

Poor coordination appears to be responsible for some expiry incidents. For example, expiry due to treatment policy change and duplicate procurement can be prevented by sound coordination between key stakeholders. Even though a medicine procurement and supply management task force was set up by Uganda’s Ministry of Health to plan the phasing out of chloroquine and sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine,13 the expiry of large stocks of the latter suggests a serious lapse in coordination. Countries undertaking similar ventures should involve their national medicine regulatory agencies at all stages of the transition process to guide local production and to curtail entry of phased-out medicines into the market well before implementation of the change. Furthermore, rigorous coordination between suppliers and their clients is critical to the success of the “pull” system of supply of medicines used by Uganda’s National Medical Stores,2,13 as it ensures that the supplier’s forecasted turnover keeps in harmony with the consumption of its clients. Similarly, better coordination between government projects or vertical programmes and public medical stores can ameliorate the problem of overstocking associated with duplicate procurement, as well as harmonize medicine quantification with prescribing habits and preferences of consumers to ensure procurement matches turnover. This can be achieved with the involvement of prescribers in determining the scope and quantities of supplies, and the use of surveys of consumer tastes and preferences to determine suitable dosage forms for example.

Medicines with slow and unpredictable turnover are generally prone to expiry. The standard approach of ordering economic quantities to optimize stock levels only works for medicines with stable consumption and is inappropriate for those with erratic demand. Rigorous vigilance in inventory management and maintenance of minimum stock levels is the best approach to reduce expiry of these medicines. Although robust international guidelines for donation of medicines have been in existence since 1996,14 national medicine regulatory authorities need to take control and enforce them in their own country.

Pharmaco-economists favour bulk purchasing for economies of scale,11 but this can lead to overstocking and thus exacerbate expiry. This can however be mitigated by appropriate procurement phasing, lean supply15 and stock rotation.4 A lean supply policy would specifically prevent expiry of items with a short shelf-life, though its effectiveness requires a robust logistics management information system.

Rigorous statistical analysis of strata was limited by our sample size. Nevertheless, comparable sample sizes have been used previously.9 Our findings (Box 1) and those of others10–12 reveal that expiry of medicines is a systemic barrier to access to medicines. We call for increased pharmacovigilance and surveillance of national pharmaceutical supply systems, as well as further research. ■

Box 1. Lessons learned.

Public medicine wholesalers need strong coordination with their clients and with vertical programmes for effective procurement.

National medicine regulatory authorities should enforce existing international guidelines to prevent dumping of donated medicine.

Medicine selection and quantification should be matched with consumer tastes and prescribing habits. Lean supply and stock rotation should be considered.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mary Nantale and Geraldine Bwete, former secretaries of the Pharmacy Department at Makerere University, and our research assistant Thomas Okello for administering some of the questionnaires.

Footnotes

Funding: This study received some financial support from the Uganda National Drug Authority.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Mwesige A. Why should drugs expire in NMS stores Kampala: New Vision; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Value for money audit report on the management of health programmes in the health sector Kampala: Ministry of Health; 2006.

- 3.National drug policy and authority statute Kampala: Republic of Uganda; 1993.

- 4.Drug management manual 2006 Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; 2006.

- 5.Levison L, Laing R. The hidden costs of essential medicines. Essent Drugs Monit. 2003;33:20–1. [Medicines Prices Special Supplement] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Operational principles of good pharmaceutical procurement Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999 (WHO/EDM/PAR/99.5).

- 7.List of registered pharmacies in Uganda Kampala: National Drug Authority; 2006.

- 8.Uganda pharmaceutical sector baseline survey Kampala: Ministry of Health; 2002.

- 9.Using indicators to measure country pharmaceutical situations: fact book on WHO Level I and Level II monitoring indicators Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muyingo S, David V, Olupot G, Ekochu E, Sebagenzi E, Kiragga D, et al. Baseline assessment of drug logistics systems in 12 DISH supported districts (draft report) Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The world medicines situation Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The report of the auditor general on the procurement and distribution of drugs at central medical stores (CMS) (performance audit report no.6) Gaborone: Republic of Botswana; 2006.

- 13.Lynch M, Koek I, Beach R, Asamoah K, Adeya G, Namboze J, et al. (2005). Country profile: Uganda Washington, DC: President’s Malaria Initiative; 2005. Available from: http://www.fightingmalaria.gov/countries/profiles/uganda_profile.pdf [accessed on 5 November 2009].

- 14.Guidelines for drug donations, 2nd edition Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999 (WHO/EDM/PAR/99.4).

- 15.Koumanakos DP. The effect of inventory management on firm performance. Int J Prod Perform Manag. 2008;57:355–69. doi: 10.1108/17410400810881827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]