Abstract

Background

Mercury is present in the Amazonian aquatic environments from both natural and anthropogenic sources. As a consequence, many riverside populations are exposed to methylmercury, a highly toxic organic form of mercury, because of their intense fish consumption. Many studies have analysed this exposure from different approaches since the early nineties. This review aims to systematize the information in spatial distribution, comparing hair mercury levels by studied population and Amazonian river basin, looking for exposure trends.

Methods

The reviewed papers were selected from scientific databases and online libraries. We included studies with a direct measure of hair mercury concentrations in a sample size larger than 10 people, without considering the objectives, approach of the study or mercury speciation. The results are presented in tables and maps by river basin, displaying hair mercury levels and specifying the studied population and health impact, if any.

Results

The majority of the studies have been carried out in communities from the central Amazonian regions, particularly on the Tapajós River basin. The results seem quite variable; hair mercury means range from 1.1 to 34.2 μg/g. Most studies did not show any significant difference in hair mercury levels by gender or age. Overall, authors emphasized fish consumption frequency as the main risk factor of exposure. The most studied adverse health effect is by far the neurological performance, especially motricity. However, it is not possible to conclude on the relation between hair mercury levels and health impact in the Amazonian situation because of the relatively small number of studies.

Conclusions

Hair mercury levels in the Amazonian regions seem to be very heterogenic, depending on several factors. There is no obvious spatial trend and there are many areas that have never been studied. Taking into account the low mercury levels currently handled as acceptable, the majority of the Amazonian populations can be considered exposed to methylmercury contamination. The situation for many of these traditional communities is very complex because of their high dependence on fish nutrients. It remains difficult to conclude on the Public Health implication of mercury exposure in this context.

Background

Since the Minamata tragedy as well as the Basra incident, methylmercury contamination has been a source of concern worldwide. There has been extensive work attempting to assess the human health impact of mercury contamination through fish, seafood or marine mammal consumption, such as the Seychelles and Faroe Islands birth cohorts and the New Zealand study [1-8].

In the Amazonian aquatic environments, mercury is present in soils, water and food chains from complex sources [9-16]. On one hand, these soils have accumulated mercury naturally through time [9]. Human activities such as deforestation and agricultural land use can mobilize mercury from soils and vegetation [14,15,17,18]. Also, the use of metallic mercury in the gold mining process can contribute to mercury contamination in these areas [10-13,16].

According to specific methylation rates, mercury compounds in certain aquatic environments can be transformed into methylmercury, the most toxic mercury compound. This organic form of mercury is easily assimilated and accumulated into the food chains, with biomagnification along the trophic levels [10]. This is the main pathway for human exposure via fish consumption.

The most deleterious and studied health effects of methylmercury are neurological dysfunctions [19-22], especially from in utero exposure [4,19,23-29]. Also, immunotoxic and citotoxic damages have been shown [30-33], as well as cardiovascular deleterious effects [5,34-37]. It was not easy to reach a consensus regarding safe values for methylmercury exposure [38]. Overall, the tendency through time has been to lower the recommended level as much as possible, in order to minimize the health risk [39,40]. Based on in utero neurological development, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives suggested a Benchmark Dose Limit (BMDL) of 14 μg/g of mercury in maternal hair, recommending a daily mercury intake lower than 1.5 μg/kg of body weight [41]. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) stated the Reference Dose (RfD) at 0.1 μg/kg/day, expecting no more than 11 μg/g of mercury in maternal hair [42]. Most researchers have handled for Amazonian populations a BMDL of 10 μg/g of hair mercury [36,43].

Amazonian riverside populations, which are amongst the highest fish consumers in the world, are exposed to mercury because of their alimentary habits. This situation has been widely studied in Brazil and French Guyana since the late eighties, showing quite complete information about the determinants of mercury exposure in these riverside populations [38,44-51]. However, there is an evident lack of data in the rest of the Amazonian countries, where there have been a few isolated studies.

We aimed to systematize the available data and extract relevant information regarding hair mercury levels and observed health effects in Amazonian populations. We focused on the spatial distribution trends, in order to compare hair mercury levels by river basin and studied population.

Methods

We used scientific databases and online libraries such as PubMed, ISI Web of Knowledge, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, SciELO, Horizon, selecting articles with "Mercury, methylmercury, Amazon, hair, human exposure, fish consumption" as main keywords. We included the websites of international public institutions such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The articles were included in this review if a measure of the hair mercury concentration was presented from the general population or a target group of an Amazonian region. We also considered similar basins in Brazil such as the Tocantins River and Guyana Plateau, because of their geographic and ecological interfaces with the Amazon regions.

Exclusion criteria were sample sizes less than 10 people, and the absence of a measure of central tendency (mean, geometric mean or median). Also, we excluded studies where the hair mercury concentration presented was an estimate calculated from the mercury concentration in fish tissue and the frequency and amount of fish consumption. In the cases where we found two or more articles corresponding to the same study and in the same population, we chose one to be represented on the maps.

We presented the results from all the selected articles in tables, showing author, study sites, sample sizes, hair mercury levels and fish consumption measures when available. The tables were organized by regions and using the same continuity given by the maps, starting with studies from Andean Amazonian countries (Table 1) and French Guyana (Table 2). Brazilian studies are presented in the following tables, divided according to the studied population or group (Tables 3, 4, 5). The studies conducted in the Tapajós River basins were presented in independent tables, also separated according to the studied population or group (Tables 6, 7, 8, 9). Finally, the studies from the Madeira River basin were displayed separately in the last table (Table 10).

Table 1.

Hair mercury levels in Andean Amazonian Countries

| Studied population | Study | N | Hg mean μg/g | Range | > 10 μg/ga | Fish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country, River Basin |

(median) [SD] |

μg/g |

||||

| General population | ||||||

| Barbieri et al. 2009 | Cachuela Esperanza | 150 | 3.76 (3.01) [2.52] | 0.42-15.65 | 3% | 10.5 meals/week |

| Bolivia, Beni River | ||||||

| Monrroy et al. 2008 | Upper Beni River | 556 | 5.3 (4.0) [4.3] | 0.08-34. | ≈ 14.0% | |

| Bolivia, Beni River | Children | 393 | 5.2 (3.9) [4.4] | 0.08-34.1 | ||

| Mothers | 163 | 5.5 (4.4) [4.1] | 0.15-20.0 | |||

| Pregnant women | 18 | 3.2 (3.3) [2.1] | 0.2-7.8 | |||

| Breastfeeding (BF) | 57 | 6.2 (5.5) [4.1] | 0.5-18.3 | |||

| Non pregnant, non BF | 93 | 5.4 (4.1) [4.1] | 0.15-20.0 | |||

| Maurice-Bourgoin et al. 2000 | Rurrenabaque | 80 | ||||

| Bolivia, Beni River | Esse-Ejjas indigenous | 37 | 9.8 | 4.3-19.5 | ||

| Webb et al. 2004 | Coca | 45 | 1.9(1.5) | 0.03-10.0 | 7.5 meals/month | |

| Ecuador, Napo River | Añangu | 27 | 8.7 (7.8) | 2.2-20.5 | 17.2 meals/month | |

| Pañacocha | 27 | 5.3 (5.0) | 1.5-13.6 | 33.9 meals/month | ||

| Children | ||||||

| Counter et al. 2005 | Nambija gold-mining | 80 | 2.8b (2.0) [17.5] | 1.0-135.0 | <10% | |

| Ecuador, Nambija River | settlement | |||||

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g. bGeometric mean.

Table 2.

Hair mercury levels in French Guyana

| Studied population |

River basin |

Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General population |

|||||||

| BASAG 2007 |

Maroni River |

Sinnamary | 285 | 1.8 | 5% | ||

| Oyapok River |

Lower Maroni River | 740 | 1.7-3.6 | 2.4% | |||

| Lower Oyapok | 144 | 1.5-3.4 | 1 person | ||||

| River | 181 | 4.6-7.2 | 7.6-18.2% | ||||

| Upper Oyapok River | |||||||

| Cordier et al. 1998 |

Maroni River Oyapok River |

11 health centers | |||||

| Adults | 255 | 3.4b | 0.2-22.0 | 12.2% | |||

| Pregnant women | 109 | 1.6b | 0.2-13.0 | 4.6% | |||

| Children | 136 | 2.5b | 0.2-31.0 | 11.8 | |||

| Fréry et al. 2001 |

Maroni River |

Cayodé, Twenké, Taluhen and Antécume-Pata |

235 | 11.4 [4.2] | 1.9-27.2 | 57.4% | 20-317 g/day |

| Mothers and their infants | |||||||

| Cordier et al. 2002 |

Maroni River Oyapok River |

Upper Maroni River |

|||||

| Children | 156 | 10.2b | 79% | 2 meals/day | |||

| Mothers | 90 | 12.7b | |||||

| Oyapok River | |||||||

| Children | 69 | 6.5b | |||||

| Mothers | 63 | 6.7b | |||||

| Lower Maroni River | |||||||

| Children | 153 | 1.4b | |||||

| Mothers | 77 | 2.8b | |||||

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g. bGeometric mean.

Table 3.

Hair mercury levels in Brazilian River Basins, General Population

| Study River Basin |

Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μ g/g |

> 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akagi et al. 1995 |

Três Bocas | 11 | 28.1 | 8.4-54.0 | ||

| Araguari River | ||||||

| Castro et al. 1991 | Surucucus, Paapiu and Mujacai areas |

162 | 3.61 | 1.4-8.1 | ||

| Branco River | ||||||

| Forsberg et al. 1995 | Various sites between Marie and Paduari Rivers |

154 | 75.5 [35.2] | 5.8-171.2 | ||

| Negro River | ||||||

| Kehrig et al. 1998 | Balbina Reservoir | 53 | 6.5 [5.4] | 1.2-22.0 | 110 g | |

| Negro River | ||||||

| Leino & Lodenius 1995 | Tucuruí area | 125 | 35.0 (29.0) | 0.9-240.0 | 11 meals/week | |

| Tocantins River | ||||||

| Pinheiro, Nakanishi et al. 2000 |

Belém | 13 | 2.0 | |||

| Tocantins River | ||||||

| Santos, Camara et al. 2002 |

Caxiuanã | 214 | 8.6 [6.3] | 0.6-46.0 | 12.3 meals/week | |

| Amazon River | ||||||

| Santos et al. 2003 |

Lower Mamoré: Pakaás Novos Indigenous Areas |

910 | 8.4 (6.9) [6.4] | 0.5-83.9 | ||

| Mamoré River | ||||||

| Soares et al. 2002 | Doutor Tanajura | 13 | (6.1) | 1.4-11.7 | ||

| Mamoré River | ||||||

| Vasconcellos et al. 1994 | Indigenous Xingu Park | 27 | 18.5 (18) [5.9] | 6.9-34.0 | ||

| Xingu River | Billings Dam | 28 | 0.9 (0.7) [0.7] | 0.3-3.0 | ||

| Controls | 25 | 1.1 (1.0) [0.6] | 0.3-2.5 | |||

| Vasconcellos et al. 2000 |

Xingu Park (13 groups) |

1.2-57.3 | ||||

| Xingu River | Highest values | 21.8 (20.8) [6.1] | ||||

| Lowest values | 3.6 (2.6) [2.4] | |||||

The Tapajós and Madeira Rivers basins are not displayed in this table (see Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 4.

Mercury levels in Brazilian River Basins, Target Groups

|

Studied population River Basin |

Location | N |

Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g |

> 10 μg/ga |

Fish consumption |

| Adults | ||||||

| Barbosa et al. 2001 |

Negro River shores |

76 | 21.4 (17.8) [12.7] | 1.7-59.0 | 79% | |

| Negro River | Men | 17 | 26.2 [13.7] | |||

| Women | 31 | 18.3 [11.1] | ||||

| Pinheiro et al. 2006 |

Panacauera | 22 | ≈ 7.0 | |||

| Tocantins River |

Pindobal Grande | 43 | ≈ 3.0 | |||

| Silva et al. 2004 |

Tabatinga | 98 | (6.4) | 1.2-17.0 | ||

| Amazon River, lakes | ||||||

| Yokoo et al. 2003 |

Pantanal region | 129 | 4.2 (3.7) [2.4] | 0.6-13.6 | ||

| Cuiabá River | ||||||

| Children | ||||||

| Barbosa et al. 2001 |

Negro River shores |

73 | 18.5 (16.4) [10.0] | 0.5-45.9 | 79% | |

| Negro River | ||||||

| Pinheiro et al. 2006 |

Pindobal Grande | 88 | ≈ 3.0 | |||

| Tocantins River | ||||||

| Pinheiro et al. 2007 |

Panacauera | 36 | 2.3 | 0.4-9.5 | 0% | |

| Tocantins River | ||||||

| Santos-Filho et al. 1993 |

Cubatão Municipality |

217 | 0.8 [0.5] | 0.2-3.0 | 0% | |

| Cubatão River |

||||||

| Tavares et al. 2005 |

Barão de Melgaço | 114 | 2.1 (1.8) [1.4] | 0.4-7.6 | 0% | 4.6 meals/week |

| Cuiabá River | Riverside communities |

72 | 5.4 (4.7) [3.4] | 0.6-17.1 | 7.8 meals/week | |

| Women | ||||||

| Pinheiro et al. 2008 |

Panacauera | 20 | 3.3 | 1.3-6.0 | 0% | |

| Tocantins River | ||||||

|

Mothers and their infants |

||||||

| Barbosa et al. 1998 |

Garimpo Maria Bonita |

|||||

| Fresco River (Xingu basin) |

Mothers | 28 | 8.1 (8.3) [3.2] | 0.8-13.7 | ||

| Infants | 54 | 7.3 (6.6) [3.5] | 2.0-20.4 | |||

The Tapajós and Madeira Rivers basins are not displayed in this table (see Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 5.

Hair mercury levels in Brazilian River Basins, Occupational Groups

| Study | Location | N | Hg mean μg/g | Range | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| River Basin | (median) [SD] | |||||

| Guimarães et al 1999 | Pracuúba Lake | 15 | 16.7 | |||

| Tartarugal Grande River (Fishermen) | Duas Bocas Lake | 15 | 28.0 | 87% | 14 meals/week (200 g per day) | |

| Groups | ||||||

| Palheta & Taylor 1995 | Garimpeiros | 20 | 0.4-32. | |||

| Gurupi River | Cachoeira Villagers | 5 | 0.8-4.6 | |||

| River dwellers | 10 | 0.2-15 |

The Tapajos and Madeira Rivers basins are not displayed in this table (see Tables 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 6.

Hair mercury levels in the Tapajós River Basin, General Population

| Study | Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akagi et al. 1995 | Rainha | 11 | 15.8 | 2.4-31.0 | ||

| Brasília Legal | 56 | 22.6 | 3.5-151.0 | |||

| Ponta de Pedra | 10 | 10.2 | 6.2-12.6 | |||

| Jacareacanga | 48 | 16.6 | 1.5-46.0 | |||

| Barbosa et al. 1997 | Apiacás Reservation | 55 | 34.2 (42.8) | ?-128 | 93% | ≈ 6 times/week |

| Crompton et al. 2002 | Jacareacanga | 205 | 8.6 | 0.3-83.2 | ||

| Dorea et al. 2005 | Kaburuá | 89 | 2.5 [1.4] | 22 g/day | ||

| Cururu Mission | 138 | 3.7 [1.6] | 32 g/day | |||

| Terra Preta | 22 | 6.0 [2.9] | 52 g/day | |||

| Kayabi | 47 | 12.8 [7.0] | 110 g/day | |||

| Malm et al. 1995 | Jacareacanga | 10 | 25.0 | 5.7-52.0 | ||

| Brasília Legal | 13-29 | 26.0 | 4.7-151.0 | |||

| Ponta de Pedra | 4-26 | 12.0 | ||||

| Santarem | 11 | 2.7 | ||||

| Pinheiro, Guimarães et al. 2000 | Rainha | 29 | 17.2 | |||

| Barreiras | 111 | 18.9 | ||||

| São Luís do Tapajós | 30 | 25.3 | ||||

| Paranα-Mirim | 21 | 9.2 | ||||

| Pinheiro, Nakanishi et al. 2000 | Rainha | 29 | 17.6 | |||

| Barreiras | 78 | 19.1 | ||||

| Santos et al. 2000 | Brasília Legal | 220 | 11.8 [8.0] | 0.5-50.0 | 10 meals/week | |

| São Luís do Tapajós | 327 | 19.9 [12.0] | 0.1-94.5 | 13 meals/week | ||

| Santana do Ituquí | 321 | 4.3 [1.9] | 0.4-11.6 | 13 meals/week | ||

| Santos, Camara et al 2002 | Santana do Ituquí | 321 | 4.3 [2.2] | 0.4-12.0 | 12.7 meals/week | |

| Aldeia do Lago Grande | 316 | 4.0 [2.1] | 0.4-12.0 | 12.0 meals/week | ||

| Vila do Tabatinga | 499 | 5.4 [3.1] | 0.4-17.0 | 10.5 meals/week | ||

| Santos, de Jesus et al. 2002 | Sai Cinza | 324 | 16.0 [18.9] | 4,5-90,4 | ||

| Silva et al. 2004 | Jacareacanga | 140 | (8.0) | 0.3-58.5 | ||

| Rio-Rato | 98 | 0.01-81.4 | ||||

a Percentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 7.

Hair mercury levels in the Tapajós River Basin, Adults

| Study | Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amorim et al. 2000 | Brasília Legal | 98 | (13.5) | 0.6-71.8 | >50% | |

| Women | (10.8) | |||||

| Men | (17.1) | |||||

| Dolbec et al. 2000 | Cametá | 68 | 10.8 (9.0) [6.1] | 61.8% of total meals | ||

| Women | 41 | 9.9 (8.0) [5.6] | >25% | |||

| Men | 27 | 12.2 (10.8) [6.8] | >50% | |||

| Fillion et al. 2006 | São Luís do Tapajós, Nova Canaã, Santo Antônio, Mussum, Vista Alegre and Açaituba |

251 | 17.8 | 0.2-77.2 | 69.7% | 6.8 meals/week |

| Lebel et al. 1997 | Brasília Legal | 96 | (12.9) | >50% | ||

| Women | (11.2) | 44.7% of total meals | ||||

| Men | (15.7) | 43.9% of total meals | ||||

| Lebel et al. 1998 | Brasília Legal | |||||

| Men | 34 | 14.3 [9.4] | ||||

| Women | 46 | 12.6 [7.0] | ||||

| Passos et al. 2007 | SLTapajós, Nova Canaã, Santo Antônio, Ipaupixuna, Novo Paraíso, Teça, Timbu, Açaituba, Campo Alegre, Samauma, Mussum, Vista Alegre and Santa Cruz |

457 | 16.8 (15.7) [10.3] | 0.2-58.3 | >50% | 6.6 meals/week |

| Pinheiro et al. 2006 | São Luís do Tapajós | 32 | ≈ 15.0 | |||

| Barreiras | 37 | ≈ 15.5 | ||||

| Silva et al. 2004 | Vila do Tabatinga | 98 | (6.4) | 1.2-17.0 |

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 8.

Hair mercury levels in the Tapajós River Basin Women and Children

| Studied population |

Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mothers and their Children |

||||||

| Grandjean et al. 1999 | Mothers | 114 | 11.6 (14.0) | |||

| Children | 11.0 (12.8) | 0.5-83.5 | 2 meals/day | |||

| Brasilia Legal | 76 | 11.9 | 0.7-35.8 | 76% | ||

| São Luís do Tapajós | 71 | 25.4 | 0.6-83.5 | 91% | ||

| Sai-Cinza | 87 | 17.7 | 7.3-63.8 | 92% | ||

| Santana do Ituquí | 105 | 3.8 | 0.5-12.4 | 2% | ||

| Children | ||||||

| Barbosa et al. 1997 | Apiacás Reservation | 28 | 29 | 86% | ||

| Dorea, Barbosa et al. 2005 | Kaburuá | 77 | 2.9 [2.1] | |||

| Cururu Mission | 86 | 4.8 [2.1] | ||||

| Kayabi | 40 | 16.6 [11.4] | ||||

| Pinheiro et al. 2007 | São Luís do Tapajós | 48 | 10.9 | 1.3-53.8 | 52% | |

| Barreiras | 84 | 6.1 | 1.4-23.6 | 21% | ||

| Women | ||||||

| Barbosa et al. 1997 | Apiacás Reservation | 13 | 41.2 | 100% | ||

| Dolbec et al. 2001 | Cametá | 98 | (12.5) | 2.9-27.0 | >50% | |

| Hacon et al. 2000 | Alta Floresta | 75 | 1.12 [1.2] | 0,05-8,2 | 0% | 8-20 g/day |

| Passos et al. 2003 | Brasília Legal | 26 | 10.0 (9.1) | 4.0-20.0 | ≈ 50% | 8 meals/week |

| Pinheiro et al. 2007 | São Luís do Tapajós | 5-14 meals/week | ||||

| Rainha, and Barreiras | ||||||

| Pregnant | 19 | 8.2 | 1.5-19.4 | 37% | ||

| Non-pregnant | 21 | 9.4 | 5.2-21.0 | 28% | ||

| Pinheiro et al. 2005 | São Luís do Tapajós | 28 | 13.7 | 3.2-30.04 | 36% | |

| Barreiras | 39 | 12.1 | 3.04-33.4 | 38% | ||

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 9.

Hair mercury levels in the Tapajós River Basin, Occupational Groups

| Study | Locations and groups |

N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harada et al. 2001 | Fishermen and families | |||||

| Barreiras | 76 | 16.4 [10.6] | 1.8-53.8 | 75% | ||

| Rainha | 12 | 14.1 [9.3] | 3.1-34.5 | 67% | ||

| São Luís do Tapajós | 44 | 20.8 [10.6] | 5.1-42.2 | 86% | ||

| Lebel et al. 1997 | Brasília Legal | |||||

| Fishermen | 14 | (27.3) | > 50% | 68.8% of total meals | ||

| Lebel et al. 1998 | Brasília Legal | |||||

| Fishermen | 11 | 23.9 [9.3] | ||||

| Santos, de Jesus et al. 2002 | Sai Cinza | 324 | 16.0 [18.9] | 4,5-90,4 | ||

| Agriculture | 127 | 17.3 | 6.8-90.4 | |||

| Gold mining | 6 | 13.8 | 10.7-18.5 | |||

| Both of the above | 25 | 13.8 | 6.9-25.7 | |||

| Others | 11 | 12.3 | 6.6-20.6 | |||

| Children up to 6 y/o | 93 | 16.8 | 4.5-66.6 | |||

| Students | 38 | 15.1 | 9.0-38.7 | |||

| Without information | 24 | 17.0 | 9.6-30.8 |

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g.

Table 10.

Hair mercury levels in the Madeira River Basin

| Studied population | Location | N | Hg mean μg/g (median) [SD] |

Range μg/g | > 10 μg/ga | Fish consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General population | ||||||

| Bastos et al. 2006 | Various populations along the Madeira River | 713 | 15.2 (12.5) [9.6] | 0.36-150.0 | >50% | 7 meals/week |

| Boischio & Barbosa 1993 | Near Porto Velho | 311 | ≈ (10) | ?-303.1 | 51% | 200 g/dayb |

| Mothers and their infants | ||||||

| Barbosa & Dorea 1998 | Near Porto Velho | |||||

| Mothers | 98 | 14.1 (12.8) [10.7] | 2.6-94.7 | >50% | ||

| Infants | 71 | 10.8 (7.8) [8.5] | 0.8-44.4 | |||

| Boschio & Cernichiari 1998 | Near Porto Velho | |||||

| Mothers | 12 | 4.0-41.0 | ||||

| Infants | 12 | 8.2-50.4 | ||||

| Boischio & Henshel 2000 | Near Porto Velho | |||||

| Mothers | 90 | 12.6 [6.5] | 15.0-45.0 | |||

| Infants | 89 | 10.2 [7.2] | 1.0-34.2 | |||

| Marques et al. 2007 | Porto Velho city | |||||

| Mothers | 82 | (5.4) | 0.4-62.4 | 1 meal/week | ||

| Infants | 82 | (1.8) | 0.02-32.9 | |||

aPercentage of the population with hair mercury levels higher than 10 μg/g. bFrom the Letter to the Editor Boischio Environ Research 2000; 82:91-92

In the cases when an article studied populations from different river basins, we presented them separately, in the corresponding basin tables.

For the design of the maps, we located each Amazonian study site using their longitude and latitude data when available in the article. Otherwise, we searched longitude and latitude data in geographic databases and using Google Earth, which allowed us to find and successfully locate the majority of the study sites. When it was not possible to identify the coordinates, we used the maps and/or site descriptions presented by the authors. We marked and named each study site on the map displaying a representation of the hair mercury levels found in this population in a six colour scale. Each individual square on the map represents a hair mercury measure and the target group used for the study, as well as the reference number. We prepared separated maps for the Madeira River, the Tapajós River and French Guiana. We also designed a map illustrating the studies that assessed health outcomes in relation to hair mercury levels in the studied populations, using a three colour scale for the different results.

Results and Discussion

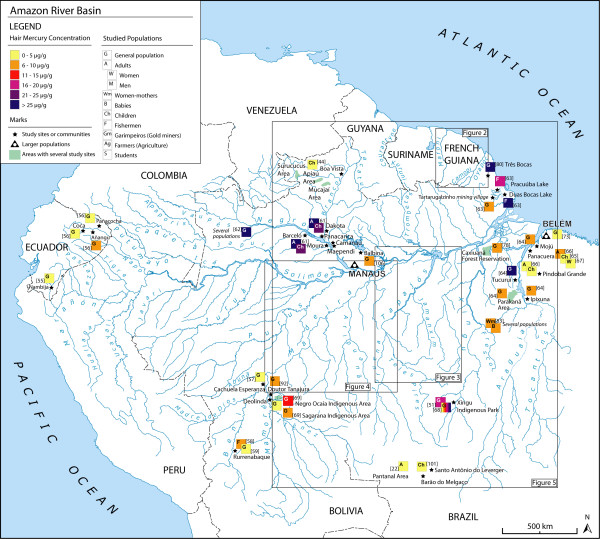

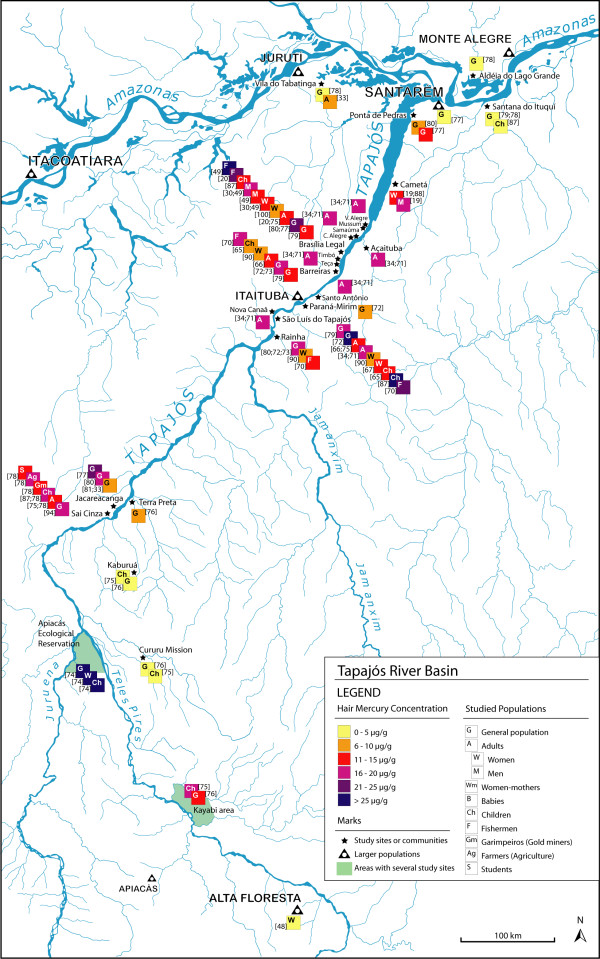

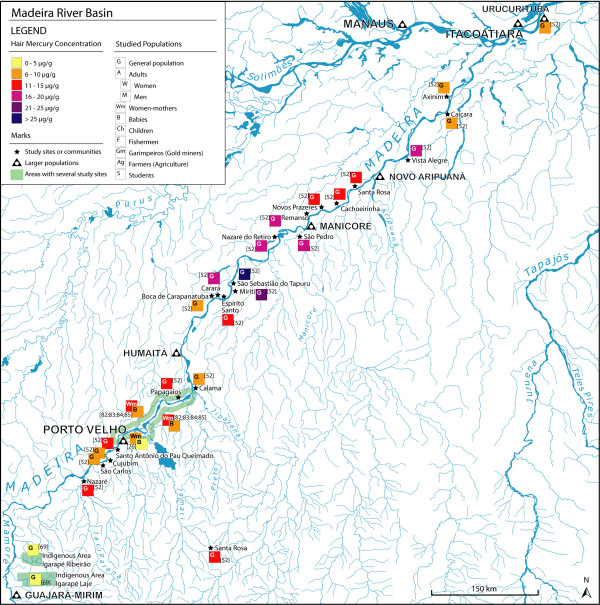

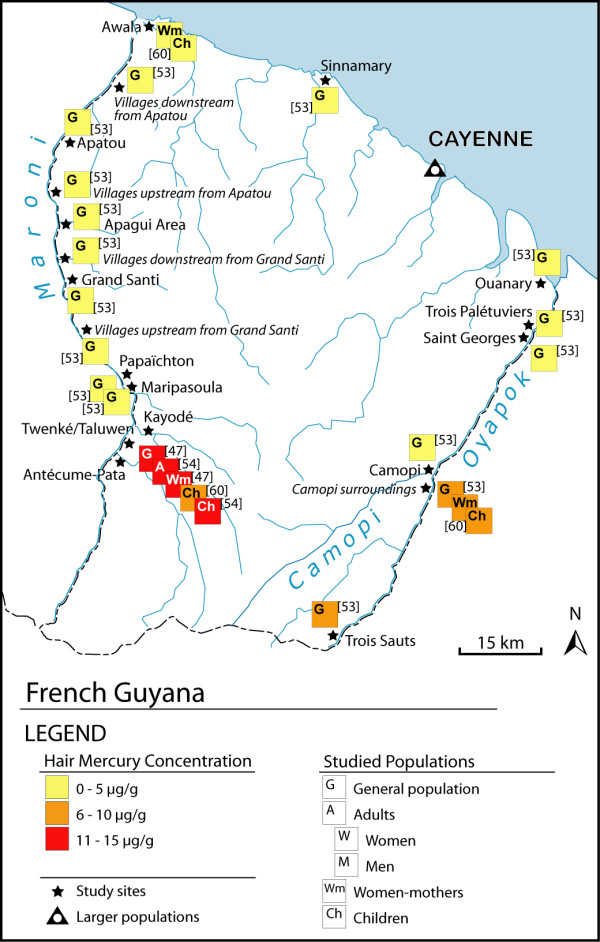

We found 58 articles meeting our criteria for the elaboration of the maps. The majority of the studies were carried out in Brazil (86%), while there are only 3 studies in French Guyana, 3 in Bolivia and 2 in Ecuador (Figures 1, 2). In Brazil, 30 studies are focused on the Tapajós River basin (Figure 3), 10 on the Madeira River basin (Figure 4) and the remaining 20% of these Brazilian studies are from other basins, such as the Negro River, the Tocantins River or the Xingu River (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hair mercury levels in the Amazon River basin.

Figure 2.

Hair mercury levels in French Guyana.

Figure 3.

Hair mercury levels in the Tapajós River basin, Brazil.

Figure 4.

Hair mercury levels in the Madeira River basin, Brazil.

The approaches and strategies are quite variable between studies. Several studies have used a large sample size, selected randomly from the general population (Tables 1, 2, 3, 6, 10), and usually comparing two or three sites from the same basin. Some of them used smaller sample sizes, accepting the variability induced by the sampling fluctuation in order to extend to several populations geographically close to each other. In the Madeira River (Figure 4; Table 10), the study by Bastos et al. (2006) covered from the upper basin (near the Bolivian border) to a point downstream on the Amazon River [52]. Even if some of the populations had sample sizes of less than 10 people, the locations evaluated were 44, distributed along the largest part of the Madeira basin (Figure 4).

In French Guiana the studies have used both approaches, covering almost the totality of the Maroni and Oyapok River basins, with large sample sizes from the general population (Figure 2; Table 2) [47,53,54].

Hair mercury levels in the Amazon

In the Andean Amazonian regions (Figure 1; Table 1), mercury levels were found below 10 μg/g in Ecuador [55,56] and Bolivia [57-59].

In French Guiana (Figure 2; Table 2), most study sites showed hair mercury levels below 10 μg/g in the Oyapok River and the lower Maroni River basins [53,60]. The only populations with mercury levels above 10 μg/g were located in an Amerindian reservation in the upper Maroni River basin [47,53,54].

In Brazilian Amazonia (Figures 1, 3, 4; Tables 3, 4, 5) hair mercury levels are very variable between basins and study sites. Without considering the studies from the Tapajós and Madeira Rivers, which will be explained in detail below, the highest mercury levels can be found in the Negro River basin [61,62] and at the lakes from the Amapá State (Figure 1; Tables 3, 4, 5) [63], with means above 20 μg/g and even higher than 25 μg/g. These high values can also be found in two other sites from the Xingu and Tocantins Rivers, both from Amerindian reservations (Figure 1) [51,64-68]. These levels can be considered of a high risk for the populations and would merit further investigations about the health impact of this exposure. The rest of these study sites show hair mercury levels below 10 μg/g, with the exception of an Amerindian reservation on the Mamoré River (13.1 μg/g) [69].

Tapajós River basin

In the Tapajós River basin (Figure 3; Tables 6, 7, 8, 9) there is a wide difference in mercury levels between the various populations. Most locations present hair mercury levels above 10 μg/g, especially in some populations such as Rainha, Barreiras, Brasília Legal or São Luís do Tapajós [34,70-73], where exposure levels seem to be alarming, even reaching a mean over 30 μg/g in the Apiacás Reservation study [74]. In very few sites the hair mercury levels remained below 5 μg/g [75,76]. The populations living in urban or suburban areas (Santarém and Santana do Ituquí) were used as control populations by the authors and showed lower exposure levels attributed to their food diversification [33,77-79]. In the same way, some authors used study sites from different river basins to compare their exposure levels, such as Panacuera or the city of Belém (Figure 1) [65,73].

Unexpectedly, studies carried out in the same site and target group obtained quite different results. For example, in Jacareacanga the studies on the general population published in 1995 [77,80] showed much higher levels (means of 16.6 and 25.0 μg/g) than those carried out in the following decade (mean = 8.6 μg/g and median = 8.0 μg/g) [33,81]. The sample sizes and study designs were very different. In 1995, Jacareacanga was a village with approximately 3000 inhabitants, and the two studies published that year took samples of 10 and 48 people. In 2002, the population of Jacareacanga was around 2000 inhabitants, and the studies published in 2002 and 2004 took samples of 140 and 205 people. Other than that, there is not enough information to explain the observed difference in hair mercury levels. There is no evidence of a change in the fish consumption frequency, deforestation, colonization, agricultural land use or gold mining activities.

Madeira River basin

In the Madeira River basin (Figure 4; Table 10) most study sites showed hair mercury levels between 11 μg/g and 15 μg/g [52,82-85]. A couple of sites (very close to each other) presented hair mercury levels above 20 μg/g [52]. A few sites showed levels between 16 μg/g and 20 μg/g and the others presented hair mercury levels under 10 μg/g [52,82,83,85]. This shows a mercury exposure distribution that appears to be less heterogenic than the Tapajós River basin. The higher mercury levels seem to be found in small isolated villages on the middle of the basin, downstream from Humaitá, near Manicoré (Figure 4).

Mercury levels and fish consumption

In the Brazilian Amazon, many studies include especially fish consumption in the population, even though not all of them show these results (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). Fish consumption is not measured in a uniform manner in all the studies. Each research team chose their indicators according to their objectives, so this measure can be found in grams per day, percentage of meals composed by fish, meals per week or per day and/or times per week. No matter which indicator for fish consumption the authors chose, there was always a positive relation between fish consumption and hair mercury levels [19,46,47,49,64,75,76]. Most of these study sites are usually small and traditional riverside villages, some of them Amerindian reservations, without the proper roads connecting them to larger villages and cities. It is possible to hypothesize that this situation makes those populations more dependent on fish as source of protein intake.

In spite of those considerations, some populations with high fish consumption showed hair mercury levels below 10 μg/g, even if there was a significant relation with fish consumption frequency [55-57,59,78,79]. In those particular six studies, it is important to consider the different geographical and socio-economic situation those populations are in: three of those studies were conducted in the Andean piedmont Amazonian regions, the two Ecuadorian studies [55,56] and one of the Bolivian studies [57]. Also, those populations are not solely dependent on fish because they are also farmers or hunters, even if fish remains the most important source of nutrients. The Bolivian population of Cachuela Esperanza, located near the Brazilian border, consumes large amounts of fish (10 fish meals per week), but only during the dry season, preferring game meat during the rainy season, which lasts from October to April [57].

The other two cases with intense fish consumption and low hair mercury levels are the studies conducted in Aldeia do Lago Grande, Santana do Ituquí and Vila to Tabatinga. These communities are located on the Amazon River shore, near the confluence with the Tapajós River. They are small but not isolated because they are connected by roads to the cities of Monte Alegre, Santarém and Juruti. The low hair mercury levels cannot be explained by food diversification, because these populations consume 10 to 13 fish meals per week. However, the fish they consume is collected from local lakes and minor rivers, and the mercury concentrations in fish tissue was found to be much lower than in other exposed populations [52,78,79].

On the Madeira River basin, where most hair mercury levels remained under 10 μg/g, the fish consumption in the majority of the populations was around seven meals per week (Table 10). On the contrary, on the Tapajós River basin the fish consumption in the majority of the populations was higher than 10 meals per week (Table 6).

Some studies measured mercury concentrations in fish tissue, finding positive relations between fish mercury concentrations, fish consumption and human hair mercury levels [13,75,77,80,86].

Studied populations

Due to the importance of mercury exposure and its health effects in children, as well as in utero exposure, many studies have chosen fertile age women and children as target groups (Tables 1, 2, 4, 8, 10). These studies are generally consistent with studies on the general population, with comparable hair mercury levels. When studied together as mother-infant pairs, there was always a strong relation between maternal hair mercury and the exposure in their infants; the mothers always had higher mercury levels than their infants [26,60,82,83,85,87].

The majority of the studies did not find any significant relationship between age and hair mercury levels [13,30,33,44,48,61,66,77,78,85,88-92]. Some studies found that hair mercury levels increase with age [74,78,79,81,84]. Nevertheless, a couple of studies found the opposite results, showing higher hair mercury levels in younger people, children and infants [58,69].

Several studies found that men have higher hair mercury levels than women [19,30,34,61,65,69,71,74,84,87]. In two articles from the Tapajós River basin, only the fishermen had hair mercury levels significantly higher than the women, while the other men from the same village presented hair mercury levels similar to those of the women (Tables 7, 8). Those differences corresponded to their fish consumption, which was also significantly higher for the fishermen [20,49]. Only one study found women to have higher mercury levels than men [69].

No study revealed physiological basis that could lead to hypothesize a difference between female and male mercury metabolism. In fact, most studies (78%) did not find any significant relation between mercury exposure and gender.

A few studies focused their attention on fishermen, because of their obvious access to fish as main nutrient [49,63,70]. Their hair mercury means ranged from 16 to more than 25 μg/g, regardless of the river basin. For instance, the studies conducted by Lebel et al. (1997, 1998) compared fishermen and other adults from the Brasilia Legal population. Both men and women had mercury levels lower than 15 μg/g, while fishermen presented levels of 27.3 μg/g and 23.9 μg/g (Figure 3; Tables 7, 8) [20,49].

The particular case of gold miners (called garimpeiros in Brazil and Bolivia) has been documented in a couple of studies. It is important to remark that occupational mercury exposure is very different from the environmental exposure. Artisanal garimpeiros are occupationally exposed to metallic mercury vapours, which are rapidly transformed in the human body into inorganic mercury, best measured in urine or plasma, while total hair mercury corresponds mainly to methylmercury exposure in high fish eating populations [36,93]. Generally, the authors found that garimpeiros had lower hair mercury levels than the ribeirinhos [58,94], concluding that because of their better economical situation, they were able to diversify their food, consuming less fish than the rest of the population[13]. However, in a few studies the garimpeiros or gold miners had higher total mercury levels in hair than the general population, without apparent relation with fish consumption frequency [45,57,95,96]. Consistently, in those three studies the hair mercury means in the general population were lower than those found in most central Amazonian studies. In both the Bolivian study and the Colombian study, hair mercury means remained below 6 μg/g, even in the most exposed groups [57,95]. It would be possible to assume that metallic mercury exposure can acquire significance in hair mercury levels in some specific situations of low methylmercury exposure. However, considering the differences between those studies and regions, and without hair mercury speciation, it is not possible to reach valid conclusions.

Multidisciplinary studies

Five studies carried out a multidisciplinary approach, measuring as well mercury in air, water, sediments, fish and human samples [13,52,58,63,96]. In those studies, human exposure seemed to be considered as a part of the totality of the environmental contamination. Therefore, those hair mercury levels were useful as a reference value for those specific study sites, and need to be interpreted in the whole context rather than as a Public Health assessment. These studies showed in a precise manner the interactions within various environmental components, showing a direct relation between mercury concentrations at different levels of the ecosystem and the food chains, including the human being as the last receptor of this pollution.

An example of an ecosystem approach is the CARUSO project [14,15,17-20,30,34,49,71,88,97-100]. This project started in 1994, and consists on a series of studies conducted by research teams of different disciplines, attempting to assess the various aspects of mercury pollution and human exposure in the Tapajós River basin.

Hair mercury levels and health impact

There were 15 studies conducted in Brazil and one in French Guyana (Figure 5). Most of them (73%) focused on neurological effects.

Figure 5.

Hair mercury levels and health impact in the Amazon River basin.

In the Amazonian context it is not easy to identify a clear relation between hair mercury levels and patent neurological abnormalities. Observing the spatial distribution of the studies, we can see that in populations with low hair mercury levels, such as Santana do Ituquí, Vila do Tabatinga or the city of Porto Velho, it was not possible to confirm a relation between mercury levels and neurological performance [26,78,79,101]. Also, in the populations with higher mercury exposure, the authors found an impact on the nervous system, especially motricity [19,20,60].

However, in São Luís do Tapajós or Brasília Legal the information is difficult to interpret. There were two studies assessing neurotoxicity in the general population and one in adults. While one of those studies documented cases of mild Minamata disease [70], the other did not find any relation between hair mercury levels and neurological outcomes [79]. On the contrary, the study conducted in adults found a dose-dependent relation between hair mercury levels and motor abnormalities [20]. There was also a study that found an association between exposure and psychomotor performance in children, but the authors concluded that the outcomes observed were also influenced by socioeconomic factors, such as maternal educational level or nutritional status [87].

Two studies have evaluated the impact of mercury exposure on the immune system in vitro. The authors found positive relations between mercury levels and the presentation of auto-antibodies [33] and cytogenetic abnormalities in peripheral lymphocytes [30], especially in the most exposed Amazonian populations.

There are a couple of studies about mercury exposure and blood pressure on the Tapajós River basin. One of them supports a negative impact of mercury exposure on the cardiovascular system [34], while the other did not find a significant relation between mercury levels and blood pressure [76]. This second study was conducted in four Amerindian populations located on rivers tributaries to the Tapajós, with low hair mercury levels. The authors found that the community with higher hair mercury levels (12.8 μg/g) seemed to be protected against age-related increase of blood pressure, because of their intense fish consumption [76].

Two studies were focused on children's growth. One of these studies was carried out in an Amerindian community from the Tapajós River [75]. No significant correlation was found between growth or nutritional status and hair mercury levels. On the contrary, a study in the Bolivian Amazonia found a positive relation between hair mercury levels and a better nutritional status in children ranging from 5 to 10 years of age [102]. Considering the characteristics of that population, the authors hypothesized that the relation observed was caused by the nutritional contents in fish, mostly important at that age group. Furthermore, the same study found the opposite result in the mothers, with worse nutritional indices in the women with higher mercury levels. In fact, while some authors worry about the health impact of mercury exposure in high fish eating populations [38,99,103], others consider that the nutritional value of fish probably compensate an exposure to low mercury levels [46,75,102,104,105]. In absence of large cohort studies, as the ones developed in the Faeroe Islands and Seychelles, the issue of health impact in the Amazonian context still remains open for debate.

Other interactions

Interest has recently been focused on the relation between mercury exposure and antioxidant defences, suggesting that long term mercury exposure induced a depletion in the antioxidant enzymatic activity [67].

Interactions between fish and fruit consumption were studied in a population from the Tapajós River, finding an inverse relationship between fruit consumption and Hg levels [71,100]. The authors recommended further investigation to establish new nutritional strategies aiming to limit mercury exposure while maintaining fish consumption.

Recently, some studies also emphasized the interactions between mercury and selenium from dietary sources, especially fish consumption [68,90,92,98]. The authors generally found high concentrations of selenium in the populations exposed to methylmercury, with molar ratios consistently close to 1. Based on their observations, the authors suggest the need of further research regarding the protective role of selenium against mercury toxicity.

Variability in exposure assessment

As seen on the maps and tables, there is a considerable spatial and temporal variability in the measure of mercury exposure. Fish consumption frequency alone does not explain the differences in hair mercury levels in some study sites. There are several factors involved: the characteristics of the soils, methylation rates in different aquatic environments, the food chain structures, specific human habits and diets, social and economic characteristics, mercury interactions with other elements, and also strong local variations without a clear explanation. Moreover, many of these small populations are subjects to intense changes through time. Human migration, land use and deforestation are usually associated with erosion peaks, which could temporarily mobilize mercury from the soils [14,15,17,18].

It is also possible to attribute some of the variations observed to the use of hair as biomarker. It has been stated that methylmercury corresponds to more than 90% of total hair mercury [19,93,106]. Therefore, total mercury in hair has been widely accepted as a well-validated methylmercury exposure marker, reflecting non-occupational exposure by seafood or fish consumption. Nevertheless, a study by Barbosa et al. (2001) in a Negro River basin population found important variations in the percentage of methylmercury in total hair mercury, ranging from 34% to 100% [61]. This variation did not seem to be influenced by age, gender, body mass index, frequency of fish consumption or total hair mercury levels. Besides, it is worth mentioning that the use of this biomarker for toxicological purposes has been criticized for its lack of reproducibility [107,108].

That sum of factors makes it difficult to assess a certain situation with exactitude in a determined population. Also, it is important to consider the variability induced by the different sampling, target populations and methodologies used by the researchers according to their objectives. Therefore, we assume that not every hair mercury value represented on the maps and tables can be completely or accurately comparable to each other for epidemiological purposes.

Conclusions

Considering the current recommendations from the environmental agencies, it is patent that almost all the Amazonian riverside populations are exposed to mercury contamination through alimentary habits. There is no evident spatial trend, even if the highest hair mercury levels were found in the central Amazonian regions, especially the Tapajós River basin. Small and isolated communities with traditional lifestyles seem to be the most exposed to mercury, regardless of the river basin. This situation is very complex for these populations, given that many of them depend on fish for economic support as well as almost unique source of dietary protein.

The available information about the health impact of this situation is not conclusive. Therefore, it becomes difficult to assess accurately the Public Health implication of mercury exposure in this particular context.

Besides, there are numerous Amazonian regions with lacking data and also with discordant results. Thus, a harmonized assessment of mercury human exposure based on a standardized approach would be valuable in order to spatially identify the most contaminated populations. This assessment would also allow prospective follow-ups of exposed populations, especially considering that these small communities are in constant evolution and subject of global changes.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

Both authors conceived the review, drafted the manuscript and designed the maps.

Contributor Information

Flavia L Barbieri, Email: flbarbieri@gmail.com.

Jacques Gardon, Email: jacques.gardon@ird.fr.

References

- Davidson PW, Myers GJ, Cox C, Wilding GE, Shamlaye CF, Huang LS, Cernichiari E, Sloane-Reeves J, Palumbo D, Clarkson TW. Methylmercury and neurodevelopment: longitudinal analysis of the Seychelles child development cohort. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PW, Palumbo D, Myers GJ, Cox C, Shamlaye CF, Sloane-Reeves J, Cernichiari E, Wilding GE, Clarkson TW. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of Seychellois children from the pilot cohort at 108 months following prenatal exposure to methylmercury from a maternal fish diet. Environ Res. 2000;84:1–11. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PW, Strain JJ, Myers GJ, Thurston SW, Bonham MP, Shamlaye CF, Stokes-Riner A, Wallace JM, Robson PJ, Duffy EM, Georger LA, Sloane-Reeves J, Cernichiari E, Canfield RL, Cox C, Huang LS, Janciuras J, Clarkson TW. Neurodevelopmental effects of maternal nutritional status and exposure to methylmercury from eating fish during pregnancy. Neurotoxicology. 2008;29:767–775. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debes F, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Weihe P, White RF, Grandjean P. Impact of prenatal methylmercury exposure on neurobehavioral function at age 14 years. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2006;28:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Murata K, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Weihe P. Cardiac autonomic activity in methylmercury neurotoxicity: 14-year follow-up of a Faroese birth cohort. J Pediatr. 2004;144:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, Needham LL, Burse VW, Patterson DG Jr, Sampson EJ, Jorgensen PJ, Vahter M. Relation of a seafood diet to mercury, selenium, arsenic, and polychlorinated biphenyl and other organochlorine concentrations in human milk. Environ Res. 1995;71:29–38. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1995.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightower JM, Moore D. Mercury levels in high-end consumers of fish. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:604–608. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellström T. Sverige. Statens naturvårdsverk: Physical and mental development of children with prenatal exposure to mercury from fish. Stage 1, Preliminary tests at age 4. City: National Swedish Environmental Protection Board [Statens naturvårdsverk]; 1986. p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Carmouze J, Boudou A, Lucotte M. Le mercure en Amazonie. Rôle de l'homme et de l'environnement, risques sanitaires. IRD, Paris; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson TW. Mercury: major issues in environmental health. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;100:31–38. doi: 10.2307/3431518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda LD, de Souza M, Ribeiro MG. The effects of land use change on mercury distribution in soils of Alta Floresta, Southern Amazon. Environ Pollut. 2004;129:247–255. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm O. Gold mining as a source of mercury exposure in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Res. 1998;77:73–78. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm O, Castro MB, Bastos WR, Branches FJP, Guimaraes JRD, Zuffo CE, Pfeiffer WC. An assessment of Hg pollution in different goldmining areas, Amazon Brazil. Science of the Total Environment. 1995;175:127–140. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04909-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roulet M, Lucotte M, Canuel R, Farella N, Courcelles M, Guimaraes JRD, Mergler D, Amorim M. Increase in mercury contamination recorded in lacustrine sediments following deforestation in the central Amazon. Chemical Geology. 2000;165:243–266. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00172-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roulet M, Lucotte M, Saint-Aubin A, Tran S, Rheault I, Farella N, De Jesus Da silva E, Dezencourt J, Sousa Passos CJ, Santos Soares G, Guimaraes JR, Mergler D, Amorim M. The geochemistry of mercury in central Amazonian soils developed on the Alter-do-Chao formation of the lower Tapajos River Valley, Para state, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 1998;223:1–24. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga MM, Maxson PA, Hylander LD. Origin and consumption of mercury in small-scale gold mining. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2006;14:436–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2004.08.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beliveau A, Lucotte M, Davidson R, Lopes LO, Paquet S. Early Hg mobility in cultivated tropical soils one year after slash-and-burn of the primary forest, in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:4480–4489. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio da Silva D, Lucotte M, Paquet S, Davidson R. Influence of ecological factors and of land use on mercury levels in fish in the Tapajos River basin, Amazon. Environ Res. 2009;109:432–446. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbec J, Mergler D, Sousa Passos CJ, Sousa de Morais S, Lebel J. Methylmercury exposure affects motor performance of a riverine population of the Tapajos river, Brazilian Amazon. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2000;73:195–203. doi: 10.1007/s004200050027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel J, Mergler D, Branches F, Lucotte M, Amorim M, Larribe F, Dolbec J. Neurotoxic effects of low-level methylmercury contamination in the Amazonian Basin. Environ Res. 1998;79:20–32. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steuerwald U, Weihe P, Jorgensen PJ, Bjerve K, Brock J, Heinzow B, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Grandjean P. Maternal seafood diet, methylmercury exposure, and neonatal neurologic function. J Pediatr. 2000;136:599–605. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.102774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoo EM, Valente JG, Grattan L, Schmidt SL, Platt I, Silbergeld EK. Low level methylmercury exposure affects neuropsychological function in adults. Environ Health. 2003;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrad DA, Bellinger DC, Ryan LM, Woodruff TJ. Dose-response relationship of prenatal mercury exposure and IQ: an integrative analysis of epidemiologic data. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:609–615. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Jorgensen PJ, Weihe P. Umbilical cord mercury concentration as biomarker of prenatal exposure to methylmercury. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113:905–908. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Weihe P, Burse VW, Needham LL, Storr-Hansen E, Heinzow B, Debes F, Murata K, Simonsen H, Ellefsen P, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Keiding N, White RF. Neurobehavioral deficits associated with PCB in 7-year-old children prenatally exposed to seafood neurotoxicants. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:305–317. doi: 10.1016/S0892-0362(01)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques RC, Garrofe Dorea J, Rodrigues Bastos W, de Freitas Rebelo M, de Freitas Fonseca M, Malm O. Maternal mercury exposure and neuro-motor development in breastfed infants from Porto Velho (Amazon), Brazil. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2007;210:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Weihe P, Budtz-Jorgensen E, Jorgensen PJ, Grandjean P. Delayed brainstem auditory evoked potential latencies in 14-year-old children exposed to methylmercury. J Pediatr. 2004;144:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez GB, Cruz MC, Pagulayan O, Ostrea E, Dalisay C. The Tagum study I: analysis and clinical correlates of mercury in maternal and cord blood, breast milk, meconium, and infants' hair. Pediatrics. 2000;106:774–781. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez GB, Pagulayan O, Akagi H, Rivera AF, Lee LV, Berroya A, Cruz MCV, Casintahan D. Tagum study II: Follow-up study at two years of age after prenatal exposure to mercury. Pediatrics. 2003;111 doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.e289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim MI, Mergler D, Bahia MO, Dubeau H, Miranda D, Lebel J, Burbano RR, Lucotte M. Cytogenetic damage related to low levels of methyl mercury contamination in the Brazilian Amazon. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2000;72:497–507. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652000000400004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenker BJ, Guo TL, Shapiro IM. Mercury-induced apoptosis in human lymphoid cells: evidence that the apoptotic pathway is mercurial species dependent. Environ Res. 2000;84:89–99. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbergeld EK, Silva IA, Nyland JF. Mercury and autoimmunity: implications for occupational and environmental health. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva IA, Nyland JF, Gorman A, Perisse A, Ventura AM, Santos EC, Souza JM, Burek CL, Rose NR, Silbergeld EK. Mercury exposure, malaria, and serum antinuclear/antinucleolar antibodies in Amazon populations in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Environ Health. 2004;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion M, Mergler D, Sousa Passos CJ, Larribe F, Lemire M, Guimaraes JR. A preliminary study of mercury exposure and blood pressure in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Health. 2006;5:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-5-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guallar E, Sanz-Gallardo MI, van't Veer P, Bode P, Aro A, Gomez-Aracena J, Kark JD, Riemersma RA, Martin-Moreno JM, Kok FJ. Mercury, fish oils, and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1747–1754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological effects of methylmercury. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. National Research Council. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen JT, Seppanen K, Nyyssonen K, Korpela H, Kauhanen J, Kantola M, Tuomilehto J, Esterbauer H, Tatzber F, Salonen R. Intake of mercury from fish, lipid peroxidation, and the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary, cardiovascular, and any death in eastern Finnish men. Circulation. 1995;91:645–655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergler D, Anderson HA, Chan LH, Mahaffey KR, Murray M, Sakamoto M, Stern AH. Methylmercury exposure and health effects in humans: a worldwide concern. Ambio. 2007;36:3–11. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[3:MEAHEI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourson ML, Wullenweber AE, Poirier KA. Uncertainties in the reference dose for methylmercury. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22:677–689. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(01)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice DC. The US EPA reference dose for methylmercury: sources of uncertainty. Environ Res. 2004;95:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives. Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants. Geneva. 2004.

- Water quality criterion for the protection of human health: methylmercury: final. Washington, DC: Office of Science and Technology, Office of Water, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2001. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Global mercury assessment. Geneva, Switzerland: UNEP Chemicals; 2002. UNEP Chemicals, Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals. [Google Scholar]

- Castro MB, Albert B, Pfeiffer WC. Mercury levels in Yanomami indians hair from Roraima, Brazil. Proc 8th Intern Conf Heavy Metals in the Environment. 1991. pp. 367–370.

- Couto RCS, Câmara VM, Sabroza PC. Intoxicação mercurial: resultados preliminares em duas áreas garimpeiras - PA. Cad Saúde Pública. 1988;4:301–315. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X1988000300005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorea JG. Fish are central in the diet of Amazonian riparians: should we worry about their mercury concentrations? Environ Res. 2003;92:232–244. doi: 10.1016/S0013-9351(02)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frery N, Maury-Brachet R, Maillot E, Deheeger M, de Merona B, Boudou A. Gold-mining activities and mercury contamination of native amerindian communities in French Guiana: key role of fish in dietary uptake. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:449–456. doi: 10.2307/3454702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacon S, Yokoo E, Valente J, Campos RC, da Silva VA, de Menezes ACC. Exposure to mercury in pregnant women from Alta Floresta-Amazon Basin, Brazil. Environmental Research. 2000;84:204–210. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel J, Roulet M, Mergler D, Lucotte M, Larribe F. Fish diet and mercury exposure in a riparian Amazonian population. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 1997;97:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Passos CJ, Mergler D. Human mercury exposure and adverse health effects in the Amazon: a review. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24(Suppl 4):s503–520. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos MBA, Saiki M, Paletti G, Pinheiro RMM, Baruzzi RG, Spindel R. Determination of mercury in head hair of brazilian populational groups by neutron-activation analysis. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry-Articles. 1994;179:369–376. doi: 10.1007/BF02040173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos WR, Gomes JP, Oliveira RC, Almeida R, Nascimento EL, Bernardi JV, de Lacerda LD, da Silveira EG, Pfeiffer WC. Mercury in the environment and riverside population in the Madeira River Basin, Amazon, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 2006;368:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulletin d'Alerte et de Surveillance Antilles Guyane. Mercury in French Guiana. Cellule Inter Régionale d'Epidémiologie Antilles Guyane - Institut de Veille Sanitaire; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cordier S, Grasmick C, Paquier-Passelaigue M, Mandereau L, Weber JP, Jouan M. Mercury exposure in French Guiana: levels and determinants. Arch Environ Health. 1998;53:299–303. doi: 10.1080/00039899809605712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Counter SA, Buchanan LH, Ortega F. Mercury levels in urine and hair of children in an Andean gold-mining settlement. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2005;11:132–137. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2005.11.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb J, Nicolas Mainville N, Mergler D, Lucotte M, Betancourt O, Davidson R, Cueva E, Quizhpe E. Mercury in Fish-eating Communities of the Andean Amazon, Napo River Valley, Ecuador. Eco Health. 2004;1:SU59–SU71. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri FL, Cournil A, Gardon J. Mercury exposure in a high fish eating Bolivian Amazonian population with intense small-scale gold-mining activities. Int J Environ Health Res. 2009;19:267–277. doi: 10.1080/09603120802559342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice-Bourgoin L, Quiroga I, Chincheros J, Courau P. Mercury distribution in waters and fishes of the upper Madeira rivers and mercury exposure in riparian Amazonian populations. Sci Total Environ. 2000;260:73–86. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(00)00542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monrroy SX, Lopez RW, Roulet M, Benefice E. Lifestyle and mercury contamination of Amerindian populations along the Beni river (lowland Bolivia) J Environ Health. 2008;71:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordier S, Garel M, Mandereau L, Morcel H, Doineau P, Gosme-Seguret S, Josse D, White R, Amiel-Tison C. Neurodevelopmental investigations among methylmercury-exposed children in French Guiana. Environ Res. 2002;89:1–11. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AC, Jardim W, Dorea JG, Fosberg B, Souza J. Hair mercury speciation as a function of gender, age, and body mass index in inhabitants of the Negro River basin, Amazon, Brazil. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2001;40:439–444. doi: 10.1007/s002440010195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg BR, Forsberg MCS, Padovani CR, Sargentini E, Malm O, Kato. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Envorinmental Mercury Pollution and its Health Effects in the in the Amazon River Basin; National Institute for Minamata Disease/UFRJ. Kato HaWCP; 1995. High levels of mercury in fish and human hair from the Rio Negro basin (Brazilian Amazon): Natural background or anthropogenic contamination? pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes JRD, Fostier AH, Forti MC, Melfi JA, Kehrig H, Mauro JBN, Malm O, Krug JF. Mercury in human and environmental samples from two lakes in Amapa, Brazilian Amazon. Ambio. 1999;28:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- Leino T, Lodenius M. Human hair mercury levels in Tucurui area, State of Para, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 1995;175:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04908-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro MC, Crespo-Lopez ME, Vieira JL, Oikawa T, Guimaraes GA, Araujo CC, Amoras WW, Ribeiro DR, Herculano AM, do Nascimento JL, Silveira LC. Mercury pollution and childhood in Amazon riverside villages. Environ Int. 2007;33:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro MC, Oikawa T, Vieira JL, Gomes MS, Guimaraes GA, Crespo-Lopez ME, Muller RC, Amoras WW, Ribeiro DR, Rodrigues AR, Cortes MI, Silveira LC. Comparative study of human exposure to mercury in riverside communities in the Amazon region. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:411–414. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro MCN, Macchi BM, Vieira JLF, Oikawa T, Amoras WW, Guimaraes GA, Costa CA, Crespo-Lopez ME, Herculano AM, Silveira LCL, do Nascimento JLM. Mercury exposure and antioxidant defenses in women: A comparative study in the Amazon. Environmental Research. 2008;107:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcellos MBA, Bode P, Paletti G, Catharino MGM, Ammerlaan AK, Saiki M, Favaro DIT, Byrne AR, Baruzzi R, Rodrigues DA. Determination of mercury and selenium in hair samples of Brazilian Indian populations living in the Amazonic region by NAA. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 2000;244:81–85. doi: 10.1023/A:1006775006509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos EC, Camara Vde M, Brabo Eda S, Loureiro EC, de Jesus IM, Fayal K, Sagica F. Mercury exposure evaluation among Pakaanova Indians, Amazon Region, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2003;19:199–206. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Nakanishi J, Yasoda E, Pinheiro MC, Oikawa T, de Assis Guimaraes G, da Silva Cardoso B, Kizaki T, Ohno H. Mercury pollution in the Tapajos River basin, Amazon: mercury level of head hair and health effects. Environ Int. 2001;27:285–290. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(01)00059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos CJ, Mergler D, Fillion M, Lemire M, Mertens F, Guimaraes JR, Philibert A. Epidemiologic confirmation that fruit consumption influences mercury exposure in riparian communities in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Res. 2007;105:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro MC, Guimaraes GA, Nakanishi J, Oikawa T, Vieira JL, Quaresma M, Cardoso B, Amoras W. Total mercury in hair samples of inhabitants of Tapajos River, Para State, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:181–184. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822000000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro Md, Nakanishi J, Oikawa T, Guimaraes G, Quaresma M, Cardoso B, Amoras WW, Harada M, Magno C, Vieira JL, Xavier MB, Bacelar DR. Methylmercury human exposure in riverside villages of Tapajos basin, Para State, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2000;33:265–269. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822000000300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AC, Garcia AM, deSouza JR. Mercury contamination in hair of riverine populations of Apiacas Reserve in the Brazilian Amazon. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 1997;97:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dorea JG, Barbosa AC, Ferrari I, De Souza JR. Fish consumption (hair mercury) and nutritional status of Amazonian Amer-Indian children. Am J Hum Biol. 2005;17:507–514. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorea JG, de Souza JR, Rodrigues P, Ferrari I, Barbosa AC. Hair mercury (signature of fish consumption) and cardiovascular risk in Munduruku and Kayabi Indians of Amazonia. Environ Res. 2005;97:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm O, Branches FJ, Akagi H, Castro MB, Pfeiffer WC, Harada M, Bastos WR, Kato H. Mercury and methylmercury in fish and human hair from the Tapajos river basin, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 1995;175:141–150. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04910-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos EC, Camara VM, Jesus IM, Brabo ES, Loureiro EC, Mascarenhas AF, Fayal KF, Sa Filho GC, Sagica FE, Lima MO, Higuchi H, Silveira IM. A contribution to the establishment of reference values for total mercury levels in hair and fish in amazonia. Environ Res. 2002;90:6–11. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos EC, Jesus IM, Brabo ES, Loureiro EC, Mascarenhas AF, Weirich J, Camara VM, Cleary D. Mercury exposures in riverside Amazon communities in Para, Brazil. Environ Res. 2000;84:100–107. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagi H, Malm O, Kinjo Y, Harada M, Branches FJP, Pfeiffer WC, Kato H. Methylmercury pollution in the Amazon, Brazil. Science of the Total Environment. 1995;175:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04905-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton P, Ventura AM, de Souza JM, Santos E, Strickland GT, Silbergeld E. Assessment of mercury exposure and malaria in a Brazilian Amazon riverine community. Environmental Research. 2002;90:69–75. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AC, Dorea JG. Indices of mercury contamination during breast feeding in the Amazon Basin. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 1998;6:71–79. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(98)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AC, Silva SR, Dorea JG. Concentration of mercury in hair of indigenous mothers and infants from the Amazon basin. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1998;34:100–105. doi: 10.1007/s002449900291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boischio AA, Barbosa A. Exposure to organic mercury in riparian populations on the Upper Madeira river, Rondonia, Brazil, 1991: preliminary results. Cad Saúde Pública. 1993;9:155–160. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X1993000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boischio AA, Henshel DS. Linear regression models of methyl mercury exposure during prenatal and early postnatal life among riverside people along the Upper Madeira river, Amazon. Environmental Research. 2000;83:150–161. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malm O, Guimaraes JRD, Castro MB, Bastos WR, Viana JP, Branches FJP, Silveira EG, Pfeiffer WC. Follow-up of mercury levels in fish, human hair and urine in the Madeira and Tapajos basins, Amazon, Brazil. Water Air and Soil Pollution. 1997;97:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, White RF, Nielsen A, Cleary D, de Oliveira Santos EC. Methylmercury neurotoxicity in Amazonian children downstream from gold mining. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:587–591. doi: 10.2307/3434402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbec J, Mergler D, Larribe F, Roulet M, Lebel J, Lucotte M. Sequential analysis of hair mercury levels in relation to fish diet of an Amazonian population, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 2001;271:87–97. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(00)00835-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacon S, Barrocas PR, Vasconcellos AC, Barcellos C, Wasserman JC, Campos RC, Ribeiro C, Azevedo-Carloni FB. An overview of mercury contamination research in the Amazon basin with an emphasis on Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2008;24:1479–1492. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2008000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro MC, Muller RC, Sarkis JE, Vieira JL, Oikawa T, Gomes MS, Guimaraes GA, do Nascimento JL, Silveira LC. Mercury and selenium concentrations in hair samples of women in fertile age from Amazon riverside communities. Sci Total Environ. 2005;349:284–288. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos Filho E, Silva Rde S, Sakuma AM, Scorsafava MA. Lead and mercury in the hair of children living in Cubatao, in the southeast region of Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 1993;27:81–86. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101993000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MC, Sarkis JE, Muller RC, Brabo ES, Santos EO. Correlation between mercury and selenium concentrations in Indian hair from Rondjnia State, Amazon region, Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 2002;287:155–161. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(01)01002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund M, Lind B, Bjornberg KA, Palm B, Einarsson O, Vahter M. Inter-individual variations of human mercury exposure biomarkers: a cross-sectional assessment. Environ Health. 2005;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos EC, de Jesus IM, Camara Vde M, Brabo E, Loureiro EC, Mascarenhas A, Weirich J, Luiz RR, Cleary D. Mercury exposure in Munduruku Indians from the community of Sai Cinza, State of Para, Brazil. Environ Res. 2002;90:98–103. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2002.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero J, Mendonza C, Mestre J. Hair mercury levels in different occupational groups in a gold mining zone in the north of Colombia. Rev Saude Publica. 1995;29:376–379. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89101995000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palheta D, Taylor A. Mercury in environmental and biological samples from a gold mining area in the Amazon region of Brazil. Sci Total Environ. 1995;168:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0048-9697(95)04533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillion M, Passos CJ, Lemire M, Fournier B, Mertens F, Guimaraes JR, Mergler D. Quality of life and health perceptions among fish-eating communities of the brazilian Amazon: an ecosystem approach to well-being. Ecohealth. 2009;6:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s10393-009-0235-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire M, Mergler D, Fillion M, Passos CJ, Guimaraes JR, Davidson R, Lucotte M. Elevated blood selenium levels in the Brazilian Amazon. Sci Total Environ. 2006;366:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergler D. Review of neurobehavioral deficits and river fish consumption from the Tapajo's (Brazil) and St. Lawrence (Canada) Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2002;12:93–99. doi: 10.1016/S1382-6689(02)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passos CJ, Mergler D, Gaspar E, Morais S, Lucotte M, Larribe F, Davidson R, de Grosbois S. Eating tropical fruit reduces mercury exposure from fish consumption in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ Res. 2003;93:123–130. doi: 10.1016/S0013-9351(03)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavares LM, Camara VM, Malm O, Santos EC. Performance on neurological development tests by riverine children with moderate mercury exposure in Amazonia, Brazil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2005;21:1160–1167. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2005000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benefice E, Monrroy SJ, Rodriguez RW. A nutritional dilemma: fish consumption, mercury exposure and growth of children in Amazonian Bolivia. Int J Environ Health Res. 2008;18:415–427. doi: 10.1080/09603120802272235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boischio AA, Henshel D. Human biomonitoring to optimize fish consumption advice: reducing uncertainty when evaluating benefits and risks. Environmental Research. 2000;84:108–126. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2000.4035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold SM, Lynn TV, Verbrugge LA, Middaugh JP. Human biomonitoring to optimize fish consumption advice: reducing uncertainty when evaluating benefits and risks. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:393–397. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorea JG. Persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic substances in fish: human health considerations. Sci Total Environ. 2008;400:93–114. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrig HA, Malm O, Akagi H, Guimaraes JR, Torres JP. Methylmercury in fish and hair samples from the Balbina Reservoir, Brazilian Amazon. Environ Res. 1998;77:84–90. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkins DK, Susten AS. Hair analysis: exploring the state of the science. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:576–578. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miekeley N, Dias Carneiro MT, da Silveira CL. How reliable are human hair reference intervals for trace elements? Sci Total Environ. 1998;218:9–17. doi: 10.1016/S0048-9697(98)00185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]