Abstract

This study directly measured the relative protein levels in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) that were cultured for two weeks in normal (5 mM, NG) or high (22 mM, HG) glucose and then were subjected to laminar shear stress at 0 or 15 dynes/cm2. Membrane preparations were labeled with one of the four isobaric tagging reagents (iTRAQ), followed by LC-MS/MS analysis. The results showed that HG and/or shear stress induced alterations in various membrane associated proteins involving many signaling pathways. While shear stress induced an increase in heat shock proteins and protein ubiquitination, which remained enhanced in HG, the effects of shear stress on the mechanosensing and protein phosphorylation pathways were altered by HG. These results were validated by Western blot analysis, suggesting that HG importantly modulates shear stress-mediated endothelial function.

Keywords: Shear stress, Endothelial cells, Hyperglycemia, Glucose, Diabetes, Proteomic profiling, iTRAQ, MS/MS

Introduction

The vascular endothelium, positioned at the interface between blood flow and the vascular wall, senses and reacts to both biochemical and mechanical changes of circulation. Blood flow generates shear stress on the vessel wall and is a major determinant in the regulation of vascular cell growth, differentiation, remodeling, metabolism, morphology, maintenance of vascular tone, and atherogenesis (Brooks et al., 2004; Cunningham et al., 2005). Endothelial cells are shear stress sensors, containing shear stress responsive and regulatory proteins. Hence, the vascular endothelium plays a pivotal role in many aspects of vascular biology, such as control of blood pressure, prevention of thrombogenesis, angiogenesis and inflammation (Langille et al., 1986; Pohl et al., 1986; Dull, 1997; Quyyumi 1998). The integrity of vascular endothelial function is known to be violated by diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and arteriosclerosis (Nakagami et al., 2005; Landmesser et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2007; Esper et al., 2008).

Hyperglycemia is the major metabolic abnormality associated with diabetes mellitus and is the initiating cause of diabetic tissue damage (Brownlee, 2005). There is a strong correlation between elevated plasma glucose levels and the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (Sowers et al., 1995; Creager et al., 2003). Cells that are unable to reduce glucose uptake when exposed to hyperglycemia, such as endothelial cells, are particularly sensitive to diabetes mellitus-mediated cell damage (Kaiser et al., 1993). Hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of diabetic vasculopathy, and this often leads to atherosclerosis, a common diabetic complication. Several mechanisms are thought to underlie hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction. First, hyperglycemia is associated with increased oxidative stress (Nakagami et al., 2005; Cohen et al., 2007). Second, hyperglycemia impairs cell function by non-enzymatic protein glycation (Vlassara et al., 1986; Aronson, 2008). Third, protein kinase C, the β isoform in particular, is activated by hyperglycemia (Avignon et al., 2006; Idris et al., 2006; Aronson, 2008). Fourth, there is heightened flux through the hexosamine pathway leading to increase in UDP N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine modification of transcription factors, which in turn result in increased expression of transforming growth factor-β1 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Brownlee, 2005). Some or all of these mechanisms may contribute to the abnormal endothelial response to shear stress in diabetes mellitus. However, little is known about the effect of hyperglycemia on the endothelial protein expression profile in response to shear stress. In this study, we used iTRAQ labeling technique coupled with LC-MS/MS to quantitatively profile the expression of proteins in bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) in response to physiological levels of laminar shear stress. We found that there were important signaling pathway modulations in BAEC by high glucose (HG), which also altered the shear stress-mediated protein profile changes. To verify the results, we performed Western blot analysis on selected protein targets. Identification of changes in shear stress responsive proteins may help advance our understanding on the role of endothelial cells in vascular homeostasis under normal conditions and in diabetes mellitus.

Materials and Methods

Endothelial Cell Culture

BAEC were obtained from Clonetics (San Diego, CA) and used between passages 2 to 5 in this study. The cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, L-glutamine (1 mM), penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml) at 37°C in the presence of humidified 95% air and 5% CO2. Cells were cultured for 2 weeks in normal glucose (NG, 5 mM D-glucose) or high glucose (HG, 22 mM D-glucose), which mimicked normal and hyperglycemia conditions, and then were seeded on glass slides (1.8 × 106 cells per slide) coated with 1% gelatin. Cells were grown to confluence in NG or HG (about 2 days) before being used for shear stress experiments.

Shear Stress Experiments

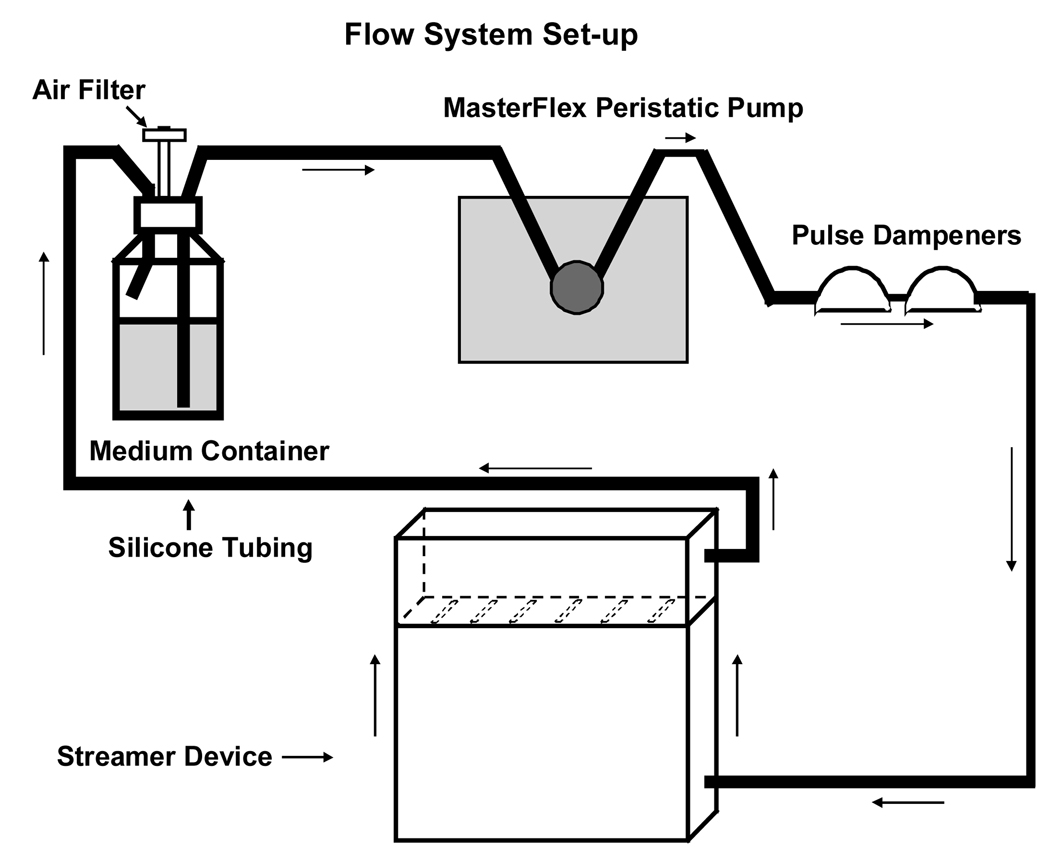

BAEC grown on gelatin-coated slides were subjected to static conditions, or physiological levels of shear stress (15 dynes/cm2) for 10 min, 3 hours, or 6 hours, using a Flexcell® Streamer® shear stress device (Flexcell International Corp.) as previously described (Archambault et al., 2002). This device consists of a parallel multi-slide flow chamber connected to a peristaltic pump (MasterFlex® L/S, Cole-Parmer Instrument Company) (Figure 1). The system is designed to allow application of fluid flow in a sterile environment. The flow perfusate was serum-free DMEM with antibiotics. The apparatus was operated in a cell culture CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells subjected to static conditions (no shear stress) served as controls. Shear stress was calculated using the following formula:

where T is the fluid shear stress in dynes/cm2, Q is the flow rate in ml/sec, μ is the viscosity in dynes • sec/cm2, h is the chamber channel height, and b is the chamber slit width (Frangos, 1988).

Figure 1. Schematic of the flow system set-up.

The Streamer device consists of a parallel-plate laminar flow chamber accommodating six 75 × 25 × 1 mm slides. This is a closed system in which the medium is re-circulated. All components of the system, except the pump, are autoclaved. A MasterFlex Pump circulates the medium through sterile MasterFlex silicone tubings (L/S 17). The pulse dampeners trap and remove air in the system.

Sample Preparation, iTRAQ Labeling and Multidimensional Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

After exposure to 10 min, 3 hours, or 6 hours of shear stress at 0 or 15 dynes/cm2, cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Plasma membrane enriched fractions were prepared by homogenizing cells in a buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 50 mM MOPS, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, pH 7.4 with EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche). The cell homogenates was centrifuged at 1,500 × g at 4°C for 15 min and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C. The membrane pellet was dissolved in iTRAQ dissolution buffer (0.5 M triethylammonium bicarbonate at pH 8.5) and protein concentrations were determined using the BioRad Protein Assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin as standards. Matched control and shear stressed NG and HG samples were labeled according to the Applied Biosystems iTRAQ protein labeling protocol (http://www.appliedbiosystems.com). All samples were digested with trypsin and labeled with one of the 4 different isotopes. Preparations from static cells in NG were labeled with iTRAQ reagent 114 and shear stressed samples were labeled with reagent 115. Preparations from cells maintained in HG were labeled with reagents 116 and 117 for static and shear stressed conditions respectively. The four samples were then combined. Excess trypsin and iTRAQ reagents were removed by a Waters C18 Sep-Pak cartridge (Milford, MA). The cleaned sample was fractionated into 10 fractions on a strong cation exchange column, Biox SCX 300 µm × 5 cm (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) using an off-line Agilent 1100 series capillary liquid chromatography system (Wilmington, DE). LC/MS/MS analysis of the peptides in each fraction was performed on an Applied Biosystems API QSTAR XL quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer using Analyst QS software (Foster City, CA). The QSTAR, configured with the Protana nano spray source (Proxeon, Denmark), was coupled to an Eksigent Nano liquid chromatography 1D Plus system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). The peptides were separated on a Zorbax C18 100 µm × 150 mm microbore column (Agilents, Wilmington, DE) with a gradient of 5% buffer B to 60% buffer B in buffer A over 120 minutes, where buffer A contained 0.1% formic acid, 98% water, 2% acetonitrile and buffer B contained 0.1% formic acid, 2% water, 98% acetonitrile. The mass spectrometry consisted of a 1 second survey scan from 350–1600 m/z and switching to 1.5 second MS/MS fragmentation scans on ions exceeding a threshold of 60 counts per second. Once the three most intense ions were fragmented in each survey scan, they were excluded from repeated fragmentation for 45 seconds. The collision energy applied varied automatically depending on the precursor m/z and charge state. The separately analyzed data from ion exchange fractions were searched against a custom bovine subset of the NCBI nr (non-redundant) database. The NCBI “nr” database is non-redundant with respect to the protein sequences, but each sequence may be associated with several identifiers from the entries in databases used to construct the “nr” database. The custom bovine subset was created by including strings with “cow,” “bovine,” and “bos taurus”, which retained 34738 entries, from the original 4930698 entries in the “nr” database. The search results were grouped using Pro Group (version 1.0; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Protein Identification, Quantification, and Data Analysis

For each MS/MS scan, ProQuant identified precursor m/z and charge in the associated TOF MS scan for that cycle. The program found the peaks in the MS/MS spectrum (or summed spectra) for the four signature ions derived from the iTRAQ reagents (114, 115, 116, 117). MS/MS results for each precursor MW-charge species were used to search the protein sequence database with the Interrogator Algorithm. Interrogator compared the fragment ion masses and precursor molecular weight to theoretical fragment ions generated in silico from the search database (“bovine,” “Bos taurus,” and “cow” subset of NCBI “nr”). The NCBI gene identifier (“gi”) accession numbers for protein database entries containing the identified peptides were recorded along with peptide sequences and area counts. Proteins with at least 75% confidence level were selected for further analysis. Proteins with one matched unique peptide were also included as positive identifications. The relative protein amount ratios above 1.2 indicate upregulation and below 0.8 down-regulation. An industry package (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, Ingenuity® Systems, Redwood City, CA) for pathway analysis was used to identify the signaling pathways that were involved in response to shear stress.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed as we have previously described (Lu et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2005). Thirty µg of cell membrane-enriched preparations were separated by 4–15% SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked for 2 hours with 10% milk in PBS, followed by incubation with monoclonal anti-ubiquitin (1:200 dilution; sc-8017, Santa Cruz), monoclonal anti-HSP70 (1:1000 dilution; SPA-810, Stressgene), monoclonal anti-phospho-PKA substrate (1:1000 dilution; 9624, Cell Signaling Technology), or polyclonal anti-pan-cadherin (1:250 dilution; 71–7100, Invitrogen) antibodies overnight at 4°C. After extensive washes with 0.1% Tween-PBS, the primary antibodies were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and the signals were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECLTM; Amersham Biosciences). The protein levels of the housekeeping gene β-actin were assayed as internal control of protein loading. The relative amounts of protein expression were further analyzed densitometrically using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT), and the results were normalized against the amounts of actin. Data are presented as means ± SE. Student’s t-test was used to compare data between two groups. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

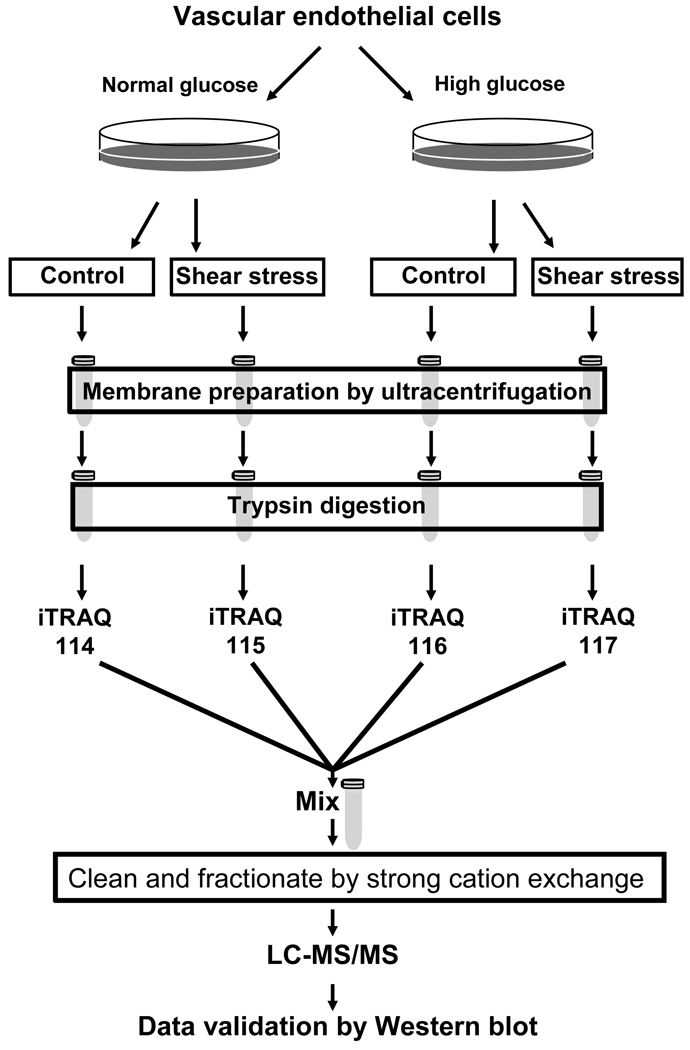

BAEC are widely used for studying the effects of laminar shear stress on the regulation of endothelial function (Go et al., 1998; Shiu et al., 2003; Lungu et al., 2004). To determine the effects of hyperglycemia on vascular endothelial cells in response to shear stress, BAEC were cultured in NG or HG for two weeks before exposure to shear stress. Membrane-enriched preparations were obtained from shear stressed and stationary control BAEC by ultracentrifugation to allow focus on the membrane subproteome, where many of the mechano-sensory and signaling transduction proteins reside. The samples were individually labeled with different iTRAQ reagents for LC-MS/MS measurements (Figure 2). Pairwise comparisons of proteomic analysis identified 243 to 571 proteins based on matching of spectra to silico trypsin digested protein sequences. Proteins identified in the study were tabulated in the Supplemental Materials. Shear stress and HG produced changes in the expression of many membrane associated proteins in BAEC (Supplemental Materials). These proteins encompass a wide spectrum of cellular functions including those involved with structural integrity, biosynthesis and metabolism, cell proliferation and apoptosis, signal transduction, and protein degradation. Some of these findings that may be pertinent to the effects of HG on shear stress-mediated regulation of vascular endothelial function are discussed below (Table 1).

Figure 2. Quantitative proteomic analysis of vascular endothelial cells in high glucose.

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) were cultured in normal (5 mM, NG) or high (22 mM, HG) glucose. Cells were either shear stressed or kept in stationary conditions (no flow) as control. Membrane fractions were prepared from the shear stressed and control cells. The membrane associated proteins were digested with trypsin, and the peptides were labeled with iTRAQ reagents. Labeled peptides were combined, fractionated by strong cation exchange chromatography, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

Table 1.

Changes in the expression of proteins induced by shear stress and by high glucose detected by LC-MS/MS.

| ACC. No | Name of Protein | Culture Treatment |

Comparison Conditions |

Fold Change |

Unique Peptide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Phosphorylation Pathways | |||||

| gi|27807059 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase | NG* | SS*** 3 hours vs. | 1.54 | 1 |

| gi|119913604 | catalytic subunit beta | NG | control | 1.69 | 1 |

| gi|78146348 | A-kinase anchor protein | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 0.53 | 1 |

| gi|119914656 | Calcineurin | NG | SS 3 hours vs. control | 0.78 | 1 |

| gi|27807059 | Protein phosphatase 2C isoform eta | HG** | SS3 hours vs. control | 0.82 | 1 |

| gi|119913604 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 0.36 | 1 |

| gi|78146348 | catalytic subunit beta | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.65 | 1 |

| gi|119914656 | A-kinase anchor protein | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.23 | 1 |

| Calcineurin | SS3 hours vs. control | ||||

| Protein phosphatase 2C isoform eta | |||||

| Mechanosensing Signaling | |||||

| gi|27807033 | platelet/endothelial cell adhesion | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 0.94 | 1 |

| gi|27807033 | molecule (PECAM) | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.37 | 1 |

| gi|27807033 | platelet/endothelial cell adhesion | HG/NG | HG vs. NG | 0.81 | 1 |

| gi|78369244 | molecule (PECAM) | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.46 | 1 |

| gi|78369244 | platelet/endothelial cell adhesion | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 0.99 | 1 |

| gi|47523792 | molecule (PECAM) | HG/NG | HG vs. NG | 0.76 | 1 |

| gi|119918497 | cadherin | HG/NG | HG vs. NG | 0.65 | 1 |

| cadherin | |||||

| catenin, beta 1 | |||||

| catenin, alpha 3 | |||||

| Protein Folding and Degradation | |||||

| gi|119920265 | HSP40 | NG | SS10 min vs. control | 1.21 | 2 |

| gi|119920265 | HSP40 | HG | SS10 min vs. control | 0.88 | 2 |

| gi|71037405 | HSP27 | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.95 | 2 |

| gi|71037405 | HSP27 | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 2.14 | 2 |

| gi|71037405 | HSP27 | NG | SS6 hours vs. control | 4.59 | 1 |

| gi|71037405 | HSP27 | HG | SS6 hours vs. control | 7.77 | 1 |

| gi|56757663 | HSP70 | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.90 | 9 |

| gi|56757663 | HSP70 | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 2.45 | 9 |

| gi|56757663 | HSP70 | NG | SS6 hours vs. control | 2.65 | 3 |

| gi|56757663 | HSP70 | HG | SS6 hours vs. control | 1.57 | 3 |

| gi|123644 | HSPA8 | NG | SS6 hours vs. control | 1.42 | 2 |

| gi|123644 | HSPA8 | HG | SS6 hours vs. control | 2.33 | 2 |

| gi|4506713 | ubiquitin and ribosomal protein S27a | NG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.57 | 7 |

| gi|4506713 | precursor | HG | SS3 hours vs. control | 1.81 | 7 |

| gi|51701919 | ubiquitin and ribosomal protein S27a | NG | SS6 hours vs. control | 3.79 | 1 |

| gi|51701919 | precursor | HG | SS6 hours vs. control | 2.32 | 1 |

| ubiquitin | |||||

| ubiquitin | |||||

NG: cells maintained in normal glucose for 2 weeks;

HG: cells maintained in high glucose for 2 weeks,

SS: shear stress.

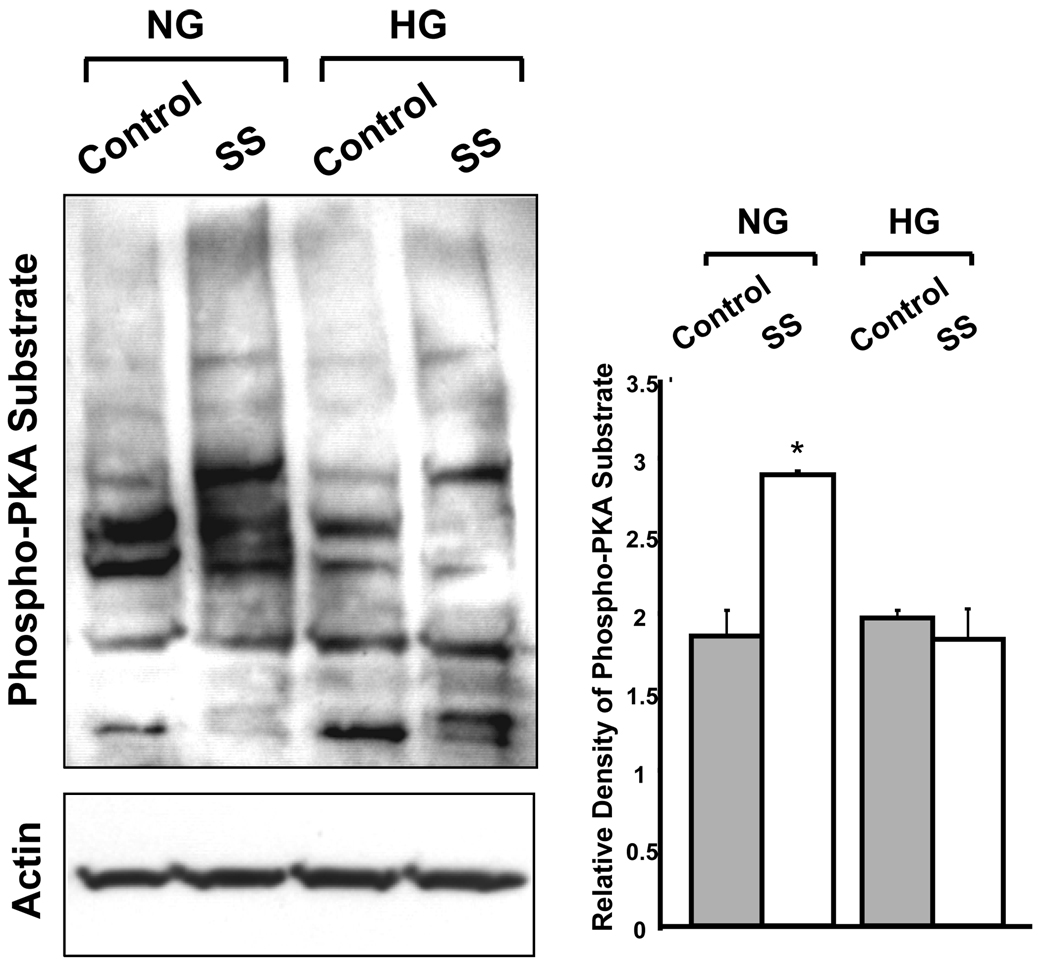

Shear Stress-Mediated Protein Phosphorylation Pathways are Altered by High Glucose

Our results showed that BAEC in HG had altered shear stress-mediated expression of protein kinase A (PKA) and its associated proteins (Table 1). In NG, shear stress induced a 54% increase in PKA and a 69% increase in A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAP) expression, while those of calcineurin, a protein phosphatase, and protein phosphatase 2C isoform-η (PP2C- η) were down-regulated by 47% and 22% respectively by shear stress. These changes suggest that shear stress would increase the level of cellular protein phosphorylation by PKA signaling in NG. In contrast, cells maintained in HG showed that the expression of calcineurin and PP2C- η were upregulated in response to shear stress by 65% and 23% respectively, while the expression of AKAP was downregulated by 64%, and that of PKA was unchanged. These results suggest that in HG, shear stress would reduce the level of protein phosphorylation and the ability to modulate cellular function by PKA-mediated mechanisms. Examination of phospho-PKA substrates in NG and HG cells by Western blot showed results consistent with those from proteomic analysis: shear stress-induced activation of PKA-mediated protein phosphorylation was impaired in cells maintained in HG (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of protein phosphorylation by PKA in BAEC.

Immunoblot analysis of phospho-PKA substrates in cells cultured in normal (5 mM, NG) or high (22 mM, HG) glucose for 2 weeks. The cells were subjected to static conditions (control) or 3 hours of shear stress (SS). Bar graph shows the densitometric analysis of three independent experiments (means ± SE) normalized to actin controls using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (*p<0.05). The results showed that shear stress-induced activation of PKA mediated protein phosphorylation was impaired in cells maintained in HG.

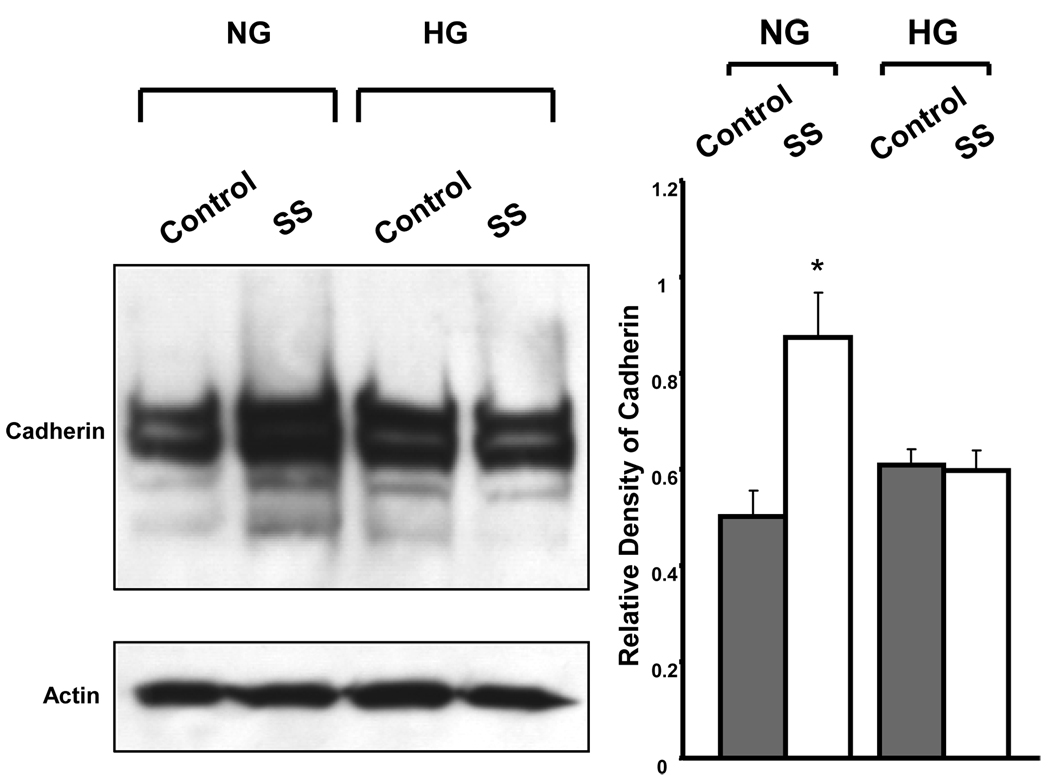

Mechanosensing Signaling Complex of Vascular Endothelium is Altered by High Glucose

Recent studies suggested that the platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1) is an important mechanoresponsive molecule (Fujiwara et al., 2001; Osawa et al., 2002; Tzima et al., 2005). An essential mechanosensory complex is formed by PECAM-1, vascular endothelial cell cadherin and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) in vascular endothelial cells. Our results showed that HG induced complex alterations in this mechanosensory complex (Table 1). Expression of PECAM-1 was reduced when BAEC were cultured in HG, compared to those in NG, under static conditions. Shear stress (3 hours) had no effects on PECAM-1 expression in cells maintained in NG, but produced a 37% increase (vs. static control) in PECAM-1 expression in cells maintained in HG. Cadherin, the adaptor protein for the mechanosensory complex, showed a 46% increase by shear stress in cells maintained in NG, but this shear stress-induced cadherin expression was lost in HG. Furthermore, expression of the α and β isoforms of catenin, a cadherin-associated protein, were suppressed by HG and unchanged by shear stress. We performed Western blot analysis on cadherin expression in the BAEC membrane enriched cell fraction, and found that cadherin was enhanced by shear stress in cells cultured in NG but not in HG (Figure 4), which is consistent with the result of proteomic analysis.

Figure 4. Western blot analysis of cadherin in BAEC.

Immunoblot analysis of cadherin in BAEC cultured in NG and HG under control conditions and after 3 hours of shear stress. Actin served as the loading control. The results showed that expression of cadherin was enhanced by shear stress in cells cultured in NG, but not in cells maintained in HG. Bar graph are expressed as the means ± SE of three independent experiments by densitometric analysis of immunoblots normalized to actin using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (*p<0.05). SS: shear stress.

Heat Shock Proteins are Enhanced by Shear Stress

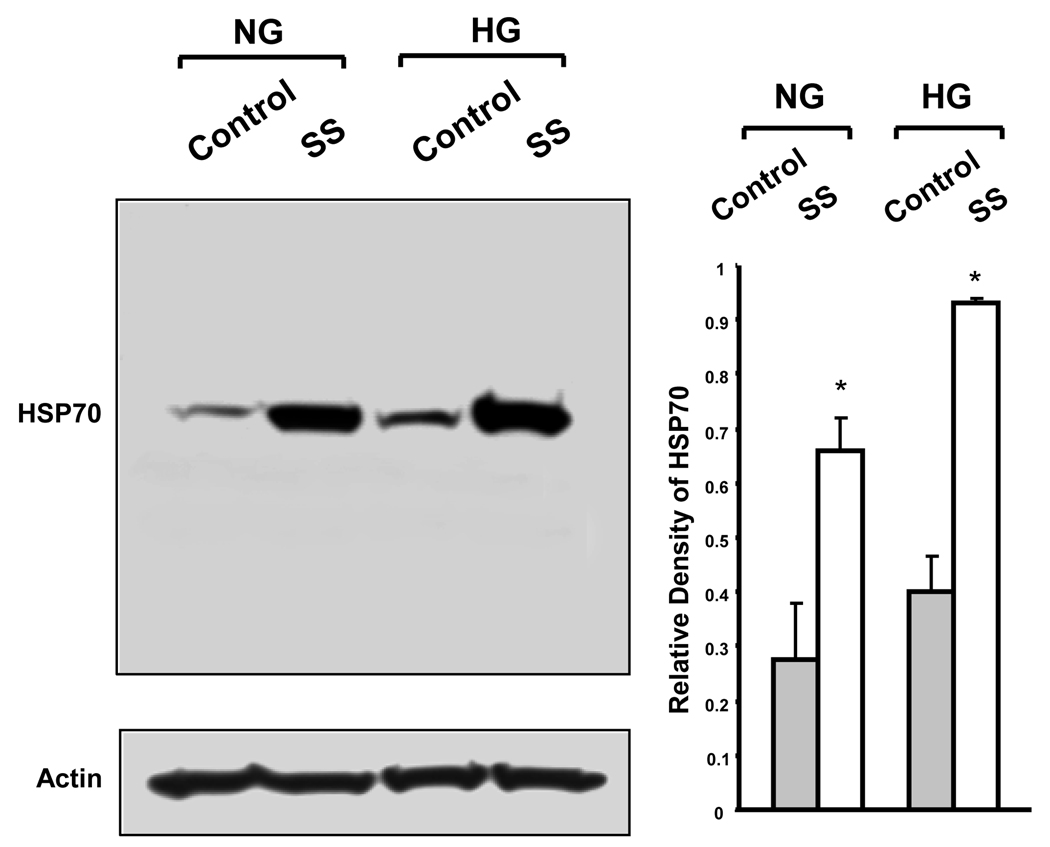

Our study detected the presence of a group of membrane associated heat shock proteins (HSPs) in BAEC, and they include HSP 27, 40, 60, 70, 71 and 90. The shear stress induced changes in HSPs are shown in Table 1. Protein levels of HSPs were not different between cells maintained in NG and HG under static culture conditions. A brief exposure to shear stress (10 min) also had little effects on these proteins. However, after 3 hours of shear stress, HSP 27 (95% in NG and 114% in HG) and HSP70 (90% in NG and 145% in HG) were up-regulated. Further upregulation in HSP 27 (up 359% in NG and 677% in HG) and HSP70 (up 165% in NG and 57% in HG) were seen after 6 hours of shear stress. In addition, shear stress induced a higher level of expression in HSP27 (20%) and HSP70 (20%) in cells maintained in HG than those in NG. The heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein, also known as HSPA8, did not change after 3 hours but increased after 6 hours of shear stress, by 42% in NG, and 133% in HG. Western blot analysis on HSP70 expression is in agreement with results obtained from proteomic analysis (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Western blot analysis of HSP70 in BAEC.

Immunoblot analysis of HSP70 in BAEC cultured in NG and HG under control conditions and after 3 hours of shear stress. Actin served as the loading control. The results showed that expression of HSP70 is enhanced in cells cultured in NG and in HG, after 3 hours of shear stress. Bar graph are expressed as the means ± SE of three independent experiments by densitometric analysis of immunoblots normalized to actin using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (*p<0.05). SS: shear stress.

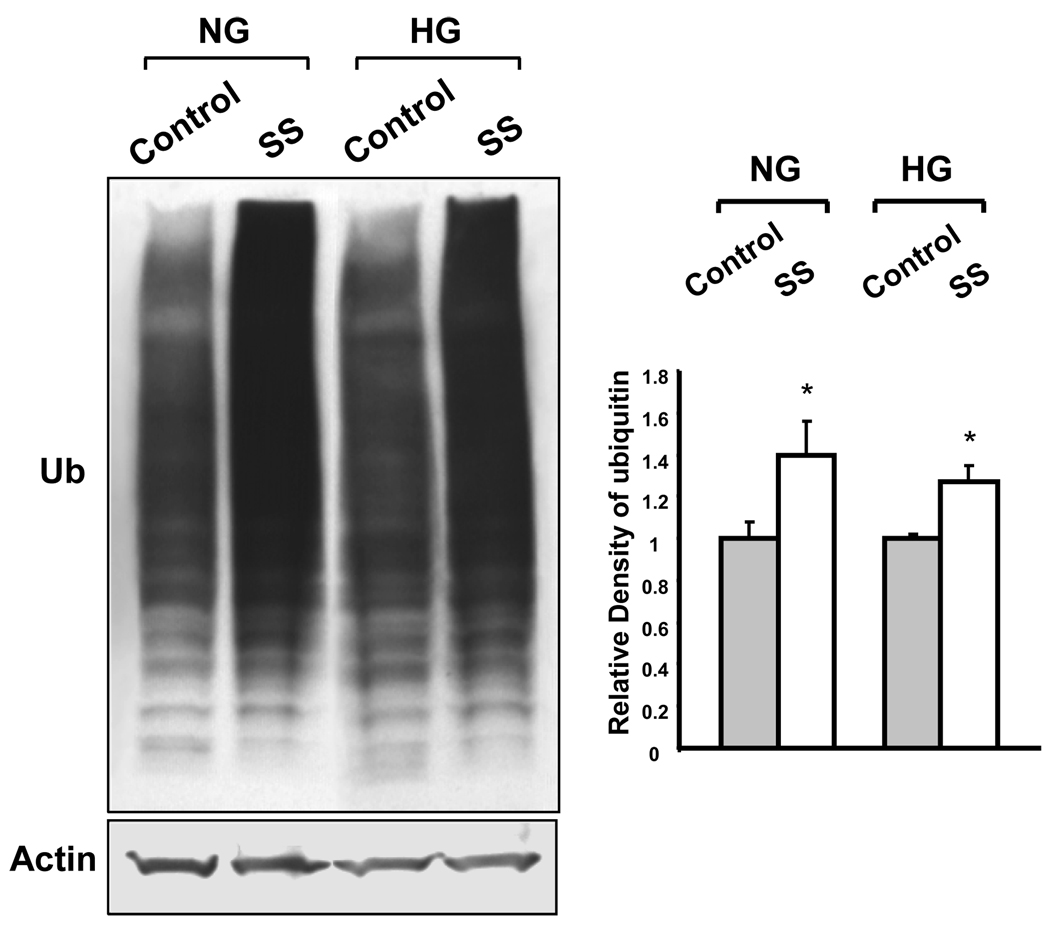

Protein Ubiquitination is Enhanced by Shear Stress

Shear stress dramatically increased the level of membrane associated ubiquitin in BAEC cultured in NG or HG, suggesting increased protein ubiquitination. After 3 hours of shear stress, the amount of membrane associated ubiquitin was up-regulated by 60% and 80% in NG and HG respectively, and was further increased by 280% and 130% respectively, after 6 hours of shear stress. Western blot analysis showed that the level of membrane associated protein ubiquitination was enhanced by 3 hours of shear stress in cells cultured in NG and HG (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Western blot analysis of ubiquitinated proteins in BAEC.

Immunoblot analysis of ubiquitinated membrane associated proteins in cells cultured in NG and HG under control conditions and after 3 hours of shear stress. Actin served as the loading control. The results showed that shear stressed cells cultured in NG and in HG had increased level of ubiquitination in a broad region of membrane proteins shown as enhanced smears. Bar graph are expressed as the means ± SE of three independent experiments by densitometric analysis of immunoblots normalized to actin using UN-SCAN-IT gel 6.1 (*p<0.05). SS: shear stress.

Many Signaling Pathways are Altered by High Glucose in Response to Shear Stress

To gain further understanding on the physiological meaning of the shear stress regulated proteins, we performed canonical pathway analysis with the proteins from Supplemental Tables A to D (Supplemental Materials) using the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) tool (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Canonical pathway analysis demonstrated that HG affected many pathways in vascular endothelial cells both in static and shear stressed state (Table 2). Specially, endothelial cells maintained in HG showed altered shear stress response in many important signaling pathways, including those of glucocorticoid receptor, nitric oxide (NO), G-protein-coupled receptor, insulin receptor and IGF-1 signaling. These findings suggest that HG is an important modulator of shear stress-mediated endothelial function.

Table 2.

Canonical pathways in BAEC altered by HG after different periods of shear stress*.

| Non- shear stress (HG/NG) | 10 min of shear stress (HG/NG) |

3 h of shear stress (HG/NG) |

6 h of shear stress (HG/NG) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Metabolism (1)** Protein Ubiquitination Pathway*** Lysine Biosynthesis (1) Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis (2) Inositol Metabolism (1) Lysine Degradation (1) Integrin Signaling (1) FGF Signaling (1) Pentose Phosphate Pathway (1) Fructose and Mannose Metabolism (1) Nitric Oxide Signaling in the Cardiovascular System (1) PDGF Signaling (1) Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling (1) Apoptosis Signaling (1) Phenylalanine, Tyrosine and Tryptophan Biosynthesis (1) Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway (1) β-alanine Metabolism (1) Propanoate Metabolism (1) Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling (2) Valine, Leucine and Isoleucine Degradation (1) Hepatic Fibrosis / Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation (1) Purine Metabolism (1) Oxidative Phosphorylation (1) Huntington's Disease Signaling (1) Ephrin Receptor Signaling (1) |

Lysine Biosynthesis (1) Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis (1) Inositol Metabolism (1) Lysine Degradation (1) Integrin Signaling (2) FGF Signaling (1) Pentose Phosphate Pathway (1) Fructose and Mannose Metabolism (1) Nitric Oxide Signaling in the Cardiovascular System (1) PDGF Signaling (1) Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling (1) Apoptosis Signaling (1) Tight Junction Signaling (1) Hepatic Fibrosis / Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation(1) NRF2-mediated Oxidative Stress Response (1) Regulation of Actin-based Motility by Rho (1) Ephrin Receptor Signaling (1) Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling (1) Leukocyte Extravasation Signaling (1) |

Protein Ubiquitination Pathway (1) Aminoacyl-tRNA Biosynthesis (2) IGF-1 Signaling (2) G-Protein Coupled Receptor Signaling (1) Pentose Phosphate Pathway (1) Sonic Hedgehog Signaling (1) Glutamate Metabolism (1) Alanine and Aspartate Metabolism (1) Nitric Oxide Signaling in the Cardiovascular System (1) Amyloid Processing (1) Phototransduction Pathway (1) Actin Cytoskeleton Signaling (1) Tight Junction Signaling (1) Hepatic Fibrosis / Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation (2) NRF2-mediated Oxidative Stress Response (1) Glycine, Serine and Threonine Metabolism (1) Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling (3) PXR/RXR Activation (1) Dopamine Receptor Signaling (1) IL-6 Signaling (2) Purine Metabolism (2) Synaptic Long Term Potentiation (1) Huntington's Disease Signaling (1) Cardiac β-adrenergic Signaling (1) Insulin Receptor Signaling (1) Mitochondrial Dysfunction (1) |

Protein Ubiquitination Pathway (3) Cell Cycle: G2/M DNA Damage Checkpoint Regulation (2) GABA Receptor Signaling (2) Hypoxia Signaling in the Cardiovascular System (2) TGF-β Signaling (2) Wnt/β-catenin Signaling (2) Synthesis and Degradation of Ketone Bodies (1) Huntington's Disease Signaling (2) Nitrogen Metabolism (1) Butanoate Metabolism (1) NRF2- mediated Oxidative Stress Response (1) |

The cutoff of up- and down-regulations was ≥ 20%;

Number of proteins matched to the pathway;

Pathways changed in 2 or more treatments are shown in bold.

Discussion

In this study, we have made several novel observations. First, HG and shear stress produced a multitude of changes in the expression of regulatory proteins in vascular endothelial cells (Table 1 and Table 2). Second, HG modified the shear stress-induced changes in endothelial protein expression in important signaling pathways, including those mediated through PKA phosphorylation. Third, expression of the mechanosensing complexes such as PECAM-1 and cadherin was altered by shear stress and modified by HG. Fourth, HSPs and ubiquitin, which are involved with regulating the stability and degradation of other cellular proteins, showed enhanced expression by shear stress with further accentuation by HG. These findings have important implications on the regulation of vascular function by blood flow in diabetes mellitus.

Protein phosphorylation has long been recognized as a key immediate response to shear stress (Dimmeler et al., 1999). Compartmentalization of the PKA effects is achieved through association with AKAPs, which are nonenzymatic scaffolding proteins that bind to the regulatory subunits of PKA while attached to cytoskeleton or organelle membrane, hence, anchoring the enzyme complex to a specific subcellular compartment. This mode of regulation ensures that PKA is exposed to isolated cAMP gradients, promoting efficient catalytic activation and accurate substrate selection (Michel et al., 2002). PKA is crucial for the regulation of many vasoactive signaling molecules by shear stress including the activation of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) (Dixit et al., 2005), and NO is one of the most potent vasodilators. Previous studies showed that shear stress-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS was mediated by a PKA-dependent and Akt-independent mechanism (Boo et al., 2002; Dixit et al., 2005), suggesting that PKA plays a critical role in shear stress-dependent activation of eNOS. In our study, HG not only abolished the shear stress-induced increase in PKA and AKAP expression, but also produced an abnormal upregulation of phosphatases. These results suggest that HG has a profound effect on vascular endothelial shear stress-mediated protein phosphorylation, converting the cells from hyper-phosphorylated to hypo-phosphorylated states. This novel finding may contribute to the hyperglycemia-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction.

Shear stress-mediated vascular endothelial response is critical for maintaining normal vascular function (Smiesko et al., 1993). It is suggested that PECAM-1 transmits the mechanical force, while cadherin acts as an adaptor, and VEGFR2 activates a PI3-kinase downstream (Tzima et al., 2005). In addition, vascular endothelial cadherin and its binding partner β-catenin are required for the formation of signaling complexes for PI3-kinase activation. (Tzima et al., 2005). Cadherin and catenin are essential elements in mechanosensing and shear stress associated signaling pathways. It has been shown that shear stress induces a rapid increase as well as the nuclear translocation of the VEGFR2, and promotes the binding of the VEGFR2 and the adherens junction molecules, cadherin and catenin, to the endothelial cytoskeleton (Shay-Salit et al., 2002). Cadherin is a major adhesive protein that interacts with the cytoskeleton, via anchoring molecules, such as β-catenin. In mice, genetic deletion of VE-cadherin results in severe vascular remodeling defects and abolition of vascular endothelial VEGFR2 signaling (Buschmann et al., 2008). Our results showed that HG abolished the shear stress-induced upregulation of cadherin, and may compromise the ability of endothelial cells to mediate shear stress-induced vascular remodeling and VGEFR2 signaling.

PECAM-1 is a membrane-bound protein (Woodfin et al., 2007) that regulates a multitude of vascular functions including angiogenesis, platelet function, thrombosis, mechanosensing of fluid shear stress, and regulation of leukocyte migration through venular walls (Woodfin et al., 2007). It is a critical component of a mechanotransducing complex that is required for the expression of proinflammatory adhesion molecules at atherosusceptible sites, and PECAM-1 has been postulated to have proatherosclerotic properties (Goel et al., 2008). HG promotes PECAM-1 phosphorylation, which results in transendothelial migration of monocytes and accelerated atherogenesis in diabetes mellitus (Rattan et al., 1996). Indeed, PECAM-1 deficient animals showed reduced atherosclerotic lesions with lowered atherogenic indices (Stevens et al., 2008). Our results showed that shear stress induced PECAM-1 over-expression only occurs in cells cultured in HG. This important finding underscores an underlying mechanism whereby hyperglycemia may contribute to the development of vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis in diabetes mellitus.

HSPs are chaperon proteins classified into six main families on the basis of their approximate molecular mass: HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP60, HSP40 and the small HSPs of less than 40 kDa. HSPs help nascent or distorted proteins to fold properly, stabilize newly synthesized polypeptides, transport proteins inside the cells, and promote lysosomal degradation of cytosolic proteins (Rawlings et al., 1994; Zolk et al., 2006). Our findings on HSPs indicated that there appeared to be increased protein degradation and turnover associated with shear stress. This upregulation of HSPs is needed to facilitate cellular remodeling as a response to shear stress and to HG. HG produces protein abnormalities through protein oxidation, nitration, and glycation. The increase in expression of HSPs may be required for proper folding and trafficking of proteins, to maintain proper protein and membrane quality control (Nakamoto et al., 2007). Indeed, induction of HSP70 has been shown to promote recovery from ischemic heart disease and diabetes (Soti et al., 2005). This important cellular regulatory process appears to be intact and is even more active in cells that have been maintained in HG for 2 weeks. However, with long-standing diabetes mellitus, the response of HSPs to stress would become impaired leading to permanent end organ damage (Hooper et al., 2005).

Ubiquitin is a highly conserved regulatory protein that is ubiquitously expressed in eukaryotes. The most prominent function of ubiquitin is to covalently modify other cellular proteins and target them for proteasomal degradation. In addition, protein ubiquitination is a common posttranslational modification (PTM) that affects the function, transport and intracellular localization of a wide variety of proteins (Hicke et al., 2003). Our result showed that shear stress dramatically increased the level of membrane associated ubiquitin and ubiquitinated proteins in BAEC cultured in NG or HG. This is consistent with our previous observation in whole-cell protein extracts of BAEC that showed shear stress dramatically increased the expression of E1-like ubiquitin-activating enzyme, which covalently coupled ubiquitin to target proteins, but reduced the expression of the ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase, a deubiquitinizing protease (Wang et al., 2007). Taken together, our results indicate that shear stress enhances the ubiquitination of membrane associated proteins and may play an important role in the regulation of protein turnover and vascular remodeling.

Many signaling pathways are known to be regulated by shear stress, including those of glucocorticoid receptor (Ji et al., 2003), nitric oxide (NO) (Li et al., 2005), G-protein-coupled receptor (Li et al., 2005), insulin receptor (Kim et al., 2001), and IGF-1 signaling (Triplett et al., 2007). However, little has been reported on how HG would affect these signaling pathways that are critical to the pathogenesis of vascular diseases linked to diabetes mellitus. Our results showed that glucocorticoid receptor signaling were down-regulated in cells maintained in HG under shear stress. Glucocorticoid is an important regulator in almost every tissue in the human body. In endothelial cells, glucocorticoid exerts antiinflammatory effects, which is considered to be atheroprotective since inflammation contributes at each stage in the development of atherosclerosis (Libby et al., 1995; Ross, 1999). Laminar shear stress has been reported to activate the glucocorticoid receptor in BAEC (Ji et al., 2003), suggesting a role for the glucocorticoid receptor pathway in mediating atheroprotective actions of shear stress in the vasculature. Our results suggest that hyperglycemia could change the consequence of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells from that of an anti-inflammatory effect into a pro-inflammatory stimulus. This may underlie how diabetes mellitus would predispose an individual to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (Sowers et al., 1995). In addition, HG induced the down regulation of NO signaling, G-protein-coupled receptor signaling, and IGF-1 signaling, and these may further contribute to endothelial cell dysfunction, with decreased endothelium-mediated vascular relaxation, increased vasoconstriction, promoting vascular smooth muscle hyperplasia, vascular remodeling, and atherosclerotic events.

The precise etiology of altered endothelial cell response to shear stress induced by HG is complex. However, the HG effects on the flow-mediated signaling pathways may promote proinflammatory and atherogenic mechanisms, which may contribute to the increased frequency, severity and rapid progression of cardiovascular diseases in diabetes mellitus. Hence, the hemodynamic environment and metabolic perturbations from hyperglycemia on vascular endothelial cells may be vital to our understanding of the pathogenesis of diabetic vasculopathy and to our ability in the development of novel therapeutic approaches.

This study provides a comprehensive approach to analyze HG-induced alterations in vascular endothelial cells in response to shear stress. Our approach allowed us to examine a relatively large number of membrane associated proteins simultaneously, and to identify unique changes in protein expressions in response to shear stress. The results from Western blot studies confirmed that our proteomic analysis results are reliable. Further studies on the functional relevance of these proteins are needed and may provide additional important insights into the mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. The major challenges will be to integrate the large body of data on shear stress-dependent endothelial protein expressions, to identify useful biomarkers for diabetes related vascular disease, and to design appropriate approaches to prevent and treat the disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (0630070N to X.W.), the National Institutes of Health (HL-80118 and HL74180 to H. L.), and the Mayo Clinic Foundation. The authors thank Godfrey C. Ford, Xuan-Mai T. Persson, Lawrence Ward and Ying Zhao for their technical assistance of the study.

Abbreviations

- BAEC

Bovine aortic endothelial cells

- iTRAQ

Isobaric tag for relative and absolute quantitation

- LC-MS/MS

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

References

- 1.Archambault JM, Elfervig-Wall MK, Tsuzaki M, Herzog W, Banes AJ. Rabbit tendon cells produce MMP-3 in response to fluid flow without significant calcium transients. J Biomech. 2002;35:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson D. Hyperglycemia and the pathobiology of diabetic complications. Adv Cardiol. 2008;45:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000115118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avignon A, Sultan A. PKC-B inhibition: a new therapeutic approach for diabetic complications. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:205–213. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boo YC, Sorescu G, Boyd N, Shiojima I, Walsh K, et al. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks AR, Lelkes PI, Rubanyi GM. Gene expression profiling of vascular endothelial cells exposed to fluid mechanical forces: relevance for focal susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Endothelium. 2004;11:45–57. doi: 10.1080/10623320490432470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownlee M. The pathobiology of diabetic complications: a unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 2005;54:1615–1625. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buschmann IR, Lehmann K, Le Noble F. Physics meets molecules: is modulation of shear stress the link to vascular prevention. Circ Res. 2008;102:510–512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen G, Riahi Y, Alpert E, Gruzman A, Sasson S. The roles of hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress in the rise and collapse of the natural protective mechanism against vascular endothelial cell dysfunction in diabetes. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2007;113:259–267. doi: 10.1080/13813450701783513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creager MA, Luscher TF, Cosentino F, Beckman JA. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Circulation. 2003;108:1527–1532. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091257.27563.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:9–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, et al. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixit M, Loot AE, Mohamed A, Fisslthaler B, Boulanger CM, et al. Gab1, SHP2, and protein kinase A are crucial for the activation of the endothelial NO synthase by fluid shear stress. Circ Res. 2005;97:1236–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000195611.59811.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dull RO, Ge M, Ryan TL, Malik AB. In: Pulmonary vascular endothelium and coagulation. Lung WJ, Crystal RG, Weibel ER, Barnes PJ, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. pp. 653–662. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esper RJ, Vilarino JO, Machado RA, Paragano A. Endothelial dysfunction in normal and abnormal glucose metabolism. Adv Cardiol. 2008;45:17–43. doi: 10.1159/000115120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frangos JA. Shear stress induced stimulation of mammalian cell metabolism. Biotechnology Bioengineering. 1988;32:1053–1060. doi: 10.1002/bit.260320812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara K, Masuda M, Osawa M, Kano Y, Katoh K. Is PECAM-1 a mechanoresponsive molecule. Cell Struct Funct. 2001;26:11–17. doi: 10.1247/csf.26.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Go YM, Park H, Maland MC, Darley-Usmar VM, Stoyanov B, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma mediates shear stress-dependent activation of JNK in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1898–H1904. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel R, Schrank BR, Arora S, Boylan B, Fleming B, et al. Site-specific effects of PECAM-1 on atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1996–2002. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hicke L, Dunn R. Regulation of membrane protein transport by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-binding proteins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:141–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.110701.154617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper PL, Hooper JJ. Loss of defense against stress: diabetes and heat shock proteins. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2005;7:204–208. doi: 10.1089/dia.2005.7.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Idris I, Donnelly R. Protein kinase C beta inhibition: A novel therapeutic strategy for diabetic microangiopathy. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3:172–178. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji JY, Jing H, Diamond SL. Shear stress causes nuclear localization of endothelial glucocorticoid receptor and expression from the GRE promoter. Circ Res. 2003;92:279–285. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000057753.57106.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaiser N, Sasson S, Feener EP, Boukobza-Vardi N, Higashi S, et al. Differential regulation of glucose transport and transporters by glucose in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Diabetes. 1993;42:80–89. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim F, Gallis B, Corson MA. TNF-alpha inhibits flow and insulin signaling leading to NO production in aortic endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:C1057–C1065. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.5.C1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landmesser U, Drexler H. Endothelial function and hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:316–320. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e3281ca710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langille BL, O’Donnell F. Reductions in arterial diameter produced by chronic decreases in blood flow are endothelium-dependent. Science. 1986;231:405–407. doi: 10.1126/science.3941904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li YS, Haga JH, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells. J Biomech. 2005;38:1949–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Libby P, Sukhova G, Lee RT, Galis ZS. Cytokines regulate vascular functions related to stability of the atherosclerotic plaque. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;2:S9–S12. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199500252-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu T, Wang XL, He T, Zhou W, Kaduce TL, et al. Impaired arachidonic acid-mediated activation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels in coronary arterial smooth muscle cells in Zucker Diabetic Fatty rats. Diabetes. 2005;54:2155–2163. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lungu AO, Jin ZG, Yamawaki H, Tanimoto T, Wong C, et al. Cyclosporin A inhibits flow-mediated activation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by altering cholesterol content in caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48794–48800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michel JJ, Scott JD. AKAP mediated signal transduction. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:235–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.083101.135801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakagami H, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T, Morishita R. Endothelial dysfunction in hyperglycemia as a trigger of atherosclerosis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1:59–63. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagami H, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T, Morishita R. Endothelial dysfunction in hyperglycemia as a trigger of atherosclerosis. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2005;1:59–63. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakamoto H, Vigh L. The small heat shock proteins and their clients. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:294–306. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osawa M, Masuda M, Kusano K, Fujiwara K. Evidence for a role of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cell mechanosignal transduction: is it a mechanoresponsive molecule. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:773–785. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pohl U, Holtz J, Busse R, Bassenge E. Crucial role of endothelium in the vasodilator response to increased flow in vivo. Hypertension. 1986;8:37–44. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.8.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quyyumi AA. Endothelial function in health and disease: new insights into the genesis of cardiovascular disease. Am J Med. 1998;105:32S–39S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rattan V, Shen Y, Sultana C, Kumar D, Kalra VK. Glucose-induced transmigration of monocytes is linked to phosphorylation of PECAM-1 in cultured endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E711–E717. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.4.E711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ. Families of cysteine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:461–486. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shay-Salit A, Shushy M, Wolfovitz E, Yahav H, Breviario F, et al. VEGF receptor 2 and the adherens junction as a mechanical transducer in vascular endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9462–9467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142224299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shiu YT, Li S, Yuan S, Wang Y, Nguyen P, et al. Shear stress-induced c-fos activation is mediated by Rho in a calcium-dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303:548–555. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smiesko V, Johnson PC. The arterial lumen is controlled by flow-related shear stress. News Physiol Sci. 1993;8:34–38. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soti C, Nagy E, Giricz Z, Vigh L, Csermely P, et al. Heat shock proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:769–780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sowers JR, Epstein M. Diabetes mellitus and associated hypertension, vascular disease, and nephropathy. An update. Hypertension. 1995;26:869–879. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.6.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stevens HY, Melchior B, Bell KS, Yun S, Yeh JC, et al. PECAM-1 is a critical mediator of atherosclerosis. Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2008;1:175–181. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Triplett JW, O’Riley R, Tekulve K, Norvell SM, Pavalko FM. Mechanical loading by fluid shear stress enhances IGF-1 receptor signaling in osteoblasts in a PKCzeta-dependent manner. Mol Cell Biomech. 2007;4:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Kiosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, et al. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vlassara H, Brownlee M, Cerami A. Nonenzymatic glycosylation: role in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Clin Chem. 1986;32:B37–B41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang XL, Fu A, Raghavakaimal S, Lee HC. Proteomic analysis of vascular endothelial cells in response to laminar shear stress. Proteomics. 2007;7:588–596. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang XL, Ye D, Peterson TE, Cao S, Shah VH, et al. Caveolae targeting and regulation of large conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11656–11664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff B, Lodziewski S, Bollmann T, Opitz CF, Ewert R. Impaired peripheral endothelial function in severe idiopathic pulmonary hypertension correlates with the pulmonary vascular response to inhaled iloprost. Am Heart J. 2007;153:1088. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.005. e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woodfin A, Voisin MB, Nourshargh S. PECAM-1: a multi-functional molecule in inflammation and vascular biology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2514–2523. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.151456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou W, Wang XL, Kaduce TL, Spector AA, Lee HC. Impaired arachidonic acid-mediated dilation of small mesenteric arteries in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H2210–H2218. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00704.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zolk O, Schenke C, Sarikas A. The ubiquitinproteasome system: focus on the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:410–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.