Abstract

Objectives

Anti-retroviral therapy regimens that include HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) are associated with diverse adverse effects including increased prevalence of oral warts, oral sensorial deficits and gastrointestinal toxicities suggesting that PIs may perturb epithelial cell biology. To test the hypothesis that PIs could affect specific biological processes of oral epithelium, the effects of these agents were evaluated in several oral epithelial cell lines.

Design

Primary and immortalized oral keratinocytes and squamous carcinoma cells of oropharyngeal origin were cultured in the presence of pharmacologically relevant concentrations of PIs. Their affects on cell viability, cytotoxicity and DNA synthesis were assessed by enzymatic assays and incorporation of 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) into DNA.

Results

Viability of primary and immortalized oral keratinocytes as well as squamous carcinoma cells of oropharyngeal origin was significantly reduced by select PIs at concentrations found in plasma. Of the seven PIs evaluated, nelfinavir was the most potent with a mean 50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] of 4.1 µM. Lopinavir and saquinavir also reduced epithelial cell viability (IC50 of 10–20 µM). Atazanavir and ritonovir caused minor reductions in viability, while amprenavir and indinavir were not significant inhibitors. The reduced cell viability, as shown by BrdU incorporation assays, was due to inhibition of DNA synthesis rather than cell death due to cytotoxicity.

Conclusion

Select PIs retard oral epithelial cell proliferation in a drug and dose dependent manner by blocking DNA synthesis. This could account for some of their adverse effects on oral health.

Keywords: Protease inhibitors, epithelial cells, viability, HAART

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has infected more than 50 million persons worldwide and progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is nearly inevitable without antiretroviral therapy. The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has dramatically reduced morbidity and mortality rates. However, some of these agents, particularly protease inhibitors (PIs), perturb biological functions and processes that can alter cell survival and induce cell death.1, 2 These pleotropic effects are associated with several clinical complications, including gastrointestinal toxicities and altered lipid metabolism.3 PIs also potently inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells,2, 3–6 prompting their use as antitumor agents in targeted clinical trials. 2, 7, 8

HAART reduces HIV loads and improves overall oral health, as demonstrated by the significant reduction of oral lesions in HIV-infected individuals.9–16 However, HAART is associated with increased incidence of oral warts,17–19 and specific drugs such as PIs are associated with adverse oral effects including oral/perioral paresthesia and taste abnormalities.14, 16, 20 Further, it has been reported that that the prevalence of oral lesions (i.e., oral candidiasis, necrotizing gingivitis/periodontitis, and oral herpesvirus infections) in HIV-infected patients undergoing HAART is significantly greater in those receiving PIs than other anti-HIV medications.21 Although this outcome could be due to differences in antiviral efficacies, it is also possible that PIs perturb the oral health of these patients by compromising epithelial cell biology. This observation, along with the propensity of the PIs to cause unintended effects, led us to evaluate PIs in several oral epithelial cell lines as a model of their effects on oral mucosa.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Cell-lines

Primary cultures of normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK), from excised tonsillar tissue, were obtained from Dr. Hollie Swanson, University of Kentucky, with appropriate Institutional Review Board approval. The immortalized keratinocyte cell lines OKF4/hTERT-1 and OKF6/hTERT-2, established by ectopic expression of the telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT) in cells from normal oral mucosal epithelium, were obtained from Dr. James Rheinwald, Harvard Medical School.22 Another hTERT-immortalized oral keratinocyte cell-line, NOK, was obtained from Dr. Karl Munger, Harvard Medical School.23 The squamous carcinoma cell lines CAL 27, derived from a tongue lesion, and FaDu, derived from a hypopharyngeal tumor, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). NHOK, OKF4/hTERT-1 (OKF4), OKF6/hTERT-2 (OKF6) and NOK cells were cultured in Keratinocyte-SFM medium supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (25 µg/mL), recombinant epidermal growth factor (0.2 ng/mL) and penicillin-streptomycin (Ker-SFM). CAL 27 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate and PS. FaDu cells were cultured in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids and PS. All cell culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Grand Rapids, NY). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Protease inhibitors

HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) nelfinavir, saquinavir, lopinavir, indinavir sulfate, atazanavir sulfate, ritonavir and amprenavir were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (www.aidsreagent.org/Index.cfm). PIs were prepared as 20 mM stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at −20°C until use.

Cell viability assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 800 cells/well in Ker-SFM. The following day, cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or varying concentrations of PIs for 48 (immortalized and carcinoma cell-lines) or 72 hrs for NHOK cells that grew more slowly. Cells were exposed to PIs at doses that spanned the typical range of plasma concentrations.24, 25 The number of viable cells per culture was determined by quantifying the conversion of resazurin to resorufin using the CellTiter-Blue viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Data for PI-treated cultures were normalized to the mean for control (DMSO-treated) cultures.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 3,200 cells/well in Ker-SFM. The next day, cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or the indicated concentration of PIs for 24 hrs. Cytotoxicity was analyzed using the MultiTox-Fluor Multiplex Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega), that determines the relative number of dead and live cells in each culture well. Data for PI-treated cultures were normalized to the mean for control (DMSO-treated) cultures and are expressed as percentage dead cells.

BrdU incorporation into cellular DNA

Cells were plated in 96-well plates at 800 cells/well in Ker-SFM. The following day, cells were treated with vehicle control (DMSO) or varying concentrations of PIs for 20 or 22 hrs. Cultures were supplemented with 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) for the last 2 hrs of PI treatment. Incorporation of BrdU into cellular DNA was determined with the Cell Proliferation ELISA, BrdU chemiluminescent assay (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as recommended by the supplier. The mean background absorbance for cells not treated with BrdU was subtracted from the values for BrdU-treated cultures, and the data were normalized to the mean level of BrdU incorporation in control (DMSO-treated) cultures.

Data analysis

Differences among treatment groups were determined by ANOVA and Fisher’s least significance test, using Statview software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values were considered significant at ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

HIV PIs reduce viability of oral epithelial cells

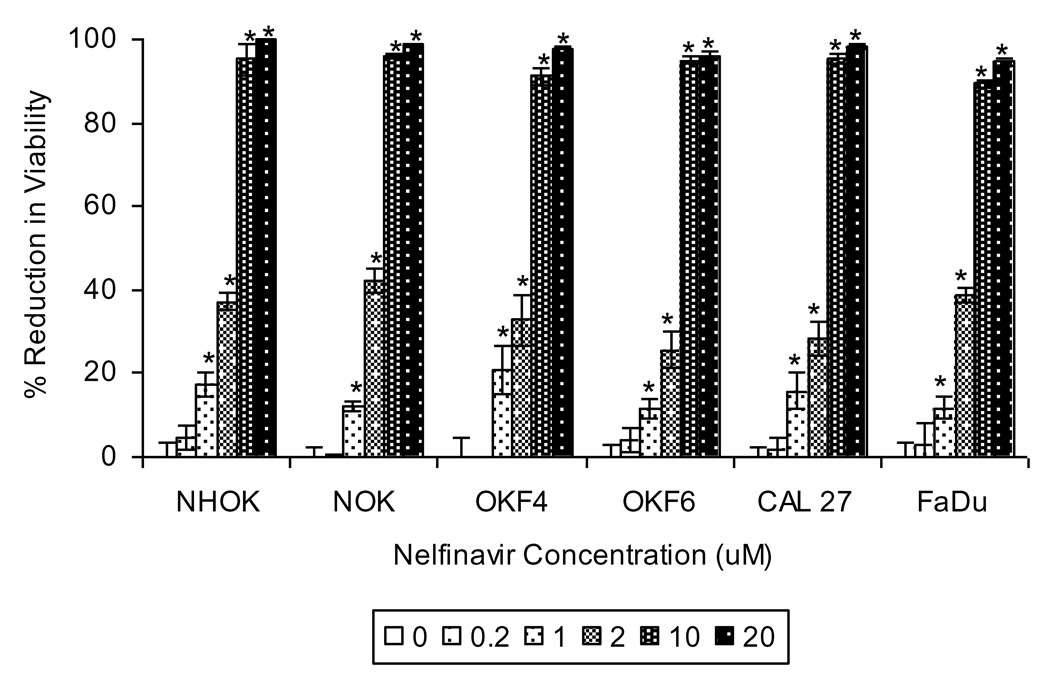

Anti-retroviral therapy regimens that include PIs are associated with increased prevalence of oral warts, oral sensorial deficits and gastrointestinal toxicities, suggesting that PIs may perturb epithelial cell biology. Accordingly, we hypothesized that PIs may affect biological processes of oral epithelial cells in ways that might contribute to these disorders. To test this hypothesis, we began by analyzing the effect of the most potent PI nelfinavir4–6 on the viability of primary oral keratinocytes, (NHOK), immortalized oral keratinocyte cell-lines (NOK, OKF4 and OKF6) and oral squamous carcinoma cell-lines (CAL 27 and FaDu). Nelfinavir reduced end-point viable cell numbers of all oral epithelial cell lines tested in a dose dependent manner, with an average IC50 of 4.1µM (Fig. 1). Concentrations of ≥10µM reduced viability of all the epithelial cell lines by more than 90%. This observation, that nelfinavir reduced viability of normal, immortalized and carcinoma cells, suggests that this PI targets important physiological pathways that are not unique to cancer cells and could influence oral epithelial health.

Figure 1. Select HIV PIs inhibit viability of oral keratinocytes.

Normal human oral keratinocytes (NHOK), immortalized oral keratinocyte cell-lines (NOK, OKF4, OKF6) and oropharyngeal squamous carcinoma cell-lines (CAL 27, FaDu) were treated with indicated concentrations of nelfinavir for 48 hrs (or 72 hrs for NHOK). Data for nelfinavir-treated cells were normalized to the mean of control (DMSO-treated) cells and are presented as mean % reduction in viability +/− standard error of the mean (SEM; n = 6). Asterisk indicates that the mean for nelfinavir-treated cells is significantly greater than the mean for DMSO-treated cells within the same cell-line (p < 0.05).

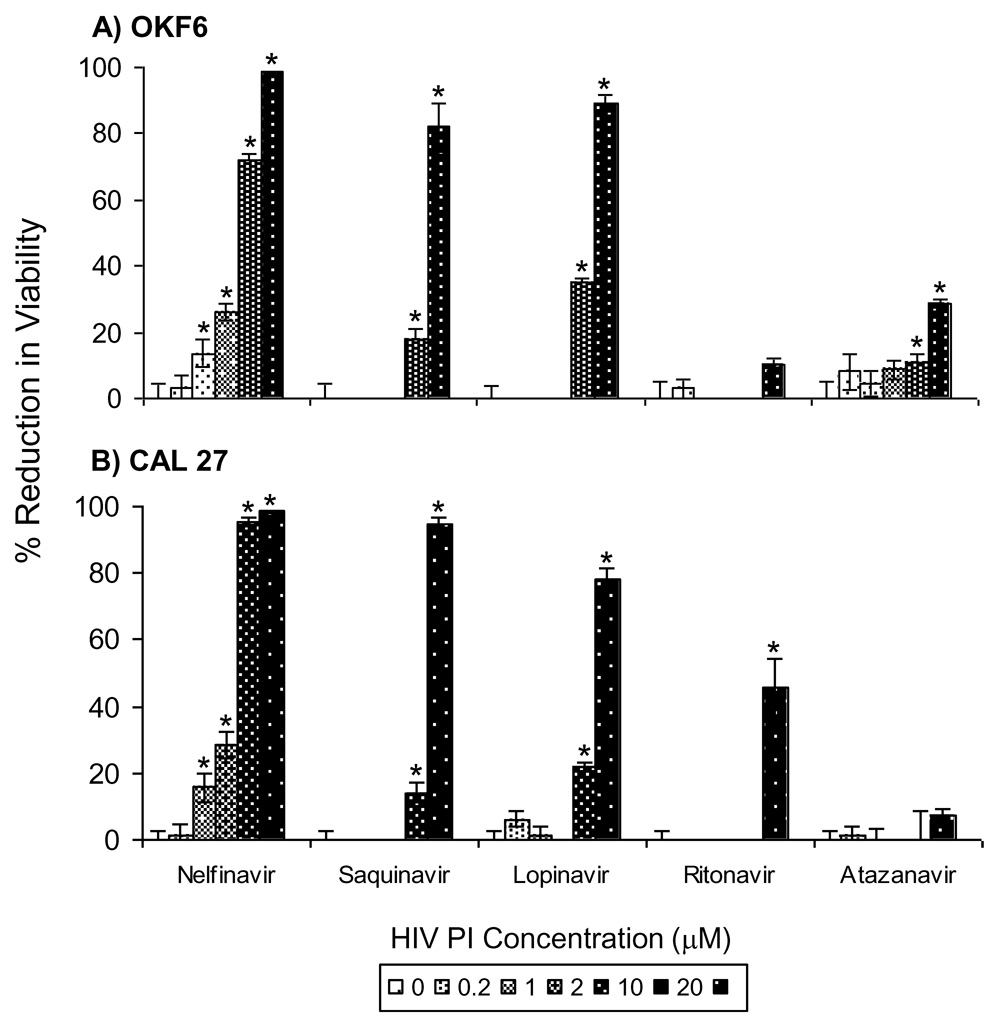

To test the potential inhibitory effects of other clinically used PIs, representative oral epithelial cell lines OKF6 and CAL 27 were treated for 48 hrs with nelfinavir, saquinavir, lopinavir, ritonavir, atazanavir, indinavir and amprenavir at doses representing the typical range of plasma concentrations in PI-treated HIV patients. Nelfinavir had the greatest inhibitory effect on cell viability of both cell-lines, with significant reductions in viability occurring at doses as low as 1 µM (Fig. 2). Saquinavir and lopinavir also reduced the viability of both cell lines, albeit at higher concentrations (≥10 µM). More modest inhibitory effects were observed with atazanavir in OKF6 cells and ritonavir in CAL 27 cells, while indinavir and amprenavir (data not shown) had no effect on cell viability of either cell line. The inhibitory effects were observed to be rapid. In subsequent studies, we found that the viability of OKF6 and CAL 27 cells was reduced by more than 50% within 24 hrs of exposure to 10 µM nelfinavir or 20 µM lopinavir (data not shown). These data indicate that select HIV PIs reduced viability of oral epithelial cells, with nelfinavir, saquinavir and lopinavir being the most potent in this capacity.

Figure 2. Effects of different HIV PIs on viability of oral keratinocytes.

The OKF6 immortalized keratinocyte cell-line (A) and the CAL 27 oropharyngeal carcinoma cell-line (B) were treated with the indicated concentrations of PIs for 48 hrs. Data for PI-treated cells were normalized to the mean of control (DMSO-treated) cells and are presented as mean % reduction in viability +/− SEM (n = 6). Asterisk indicates that the mean for PI-treated cells is significantly greater than the mean for DMSO-treated cells within the same cell-line (p < 0.05). Significant reduction in viability was not observed in cells treated with indinavir and amprenavir (data not shown).

Inhibitory effects of nelfinavir and lopinavir on viability of oral epithelial cells is not due to cell death

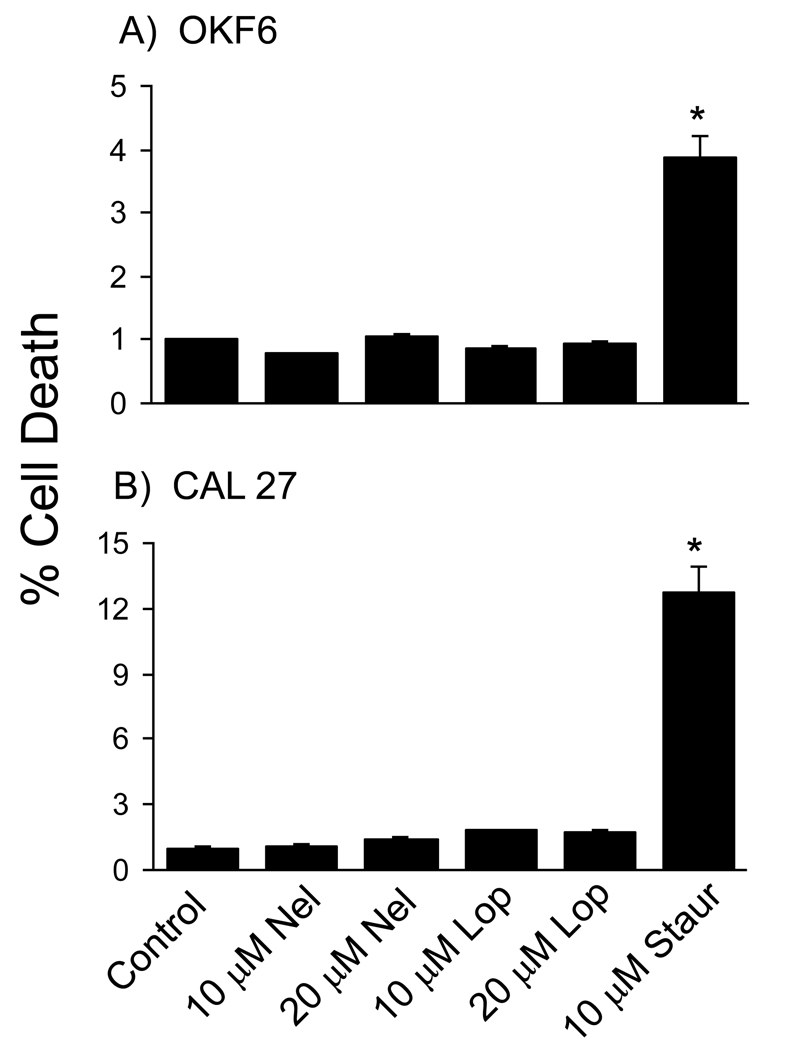

The decrease in cell viability caused by PIs could be due to increased cell death, decreased cellular proliferation, or both. To examine the cytotoxic effects of the most potent PIs, rates of cell death were analyzed in OKF6 and CAL 27 cells treated for 24 hrs with 10 or 20 µM nelfinavir or lopinavir. Although nelfinavir and lopinavir inhibited viability in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2), neither caused significant amounts of cell death in either cell line at this time point (Fig. 3). As a positive control, significant cell death was observed in both cell lines following treatment with 10 µM staurosporine. Similar results were obtained with the FaDu oral carcinoma cell-line (data not shown). These results indicate that nelfinavir and lopinavir did not directly kill oral epithelial cells at concentrations that caused significant reductions in cell viability.

Figure 3. Inhibitory effects of nelfinavir and lopinavir on viability of oral keratinocytes is not due to cell death.

The OKF6 immortalized oral keratinocyte cell-line (A) and the oropharyngeal carcinoma cell-line CAL 27 (B) were treated for 24 hrs with indicated concentrations of nelfinavir (Nel), lopinavir (Lop) or staurosporine (Staur). The % cell death was determined by the relative activities of dead cell- and live cell-specific protease activities as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as mean +/− SEM (n = 6). Asterisk indicates that the mean for treated cells is significantly different from the mean control (DMSO-treated) cells (p < 0.05).

HIV PIs block DNA synthesis in oral epithelial cells

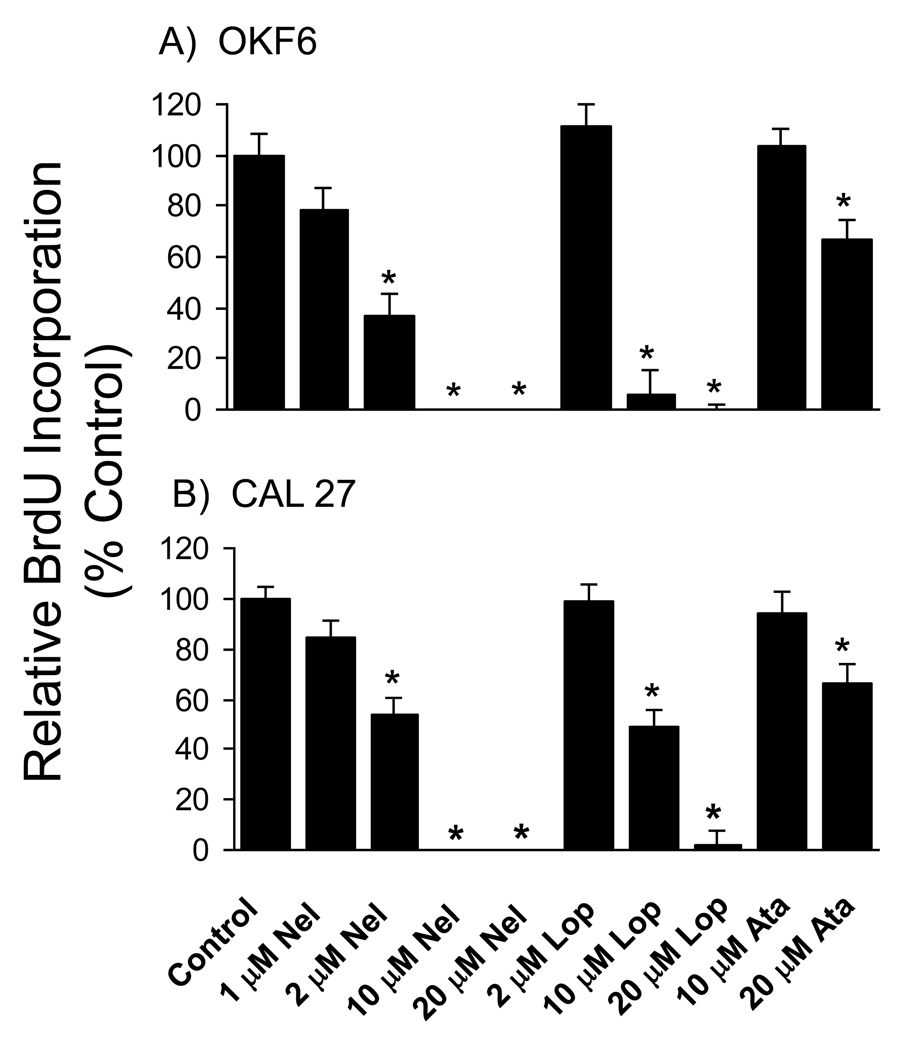

Because the PIs did not result in cell death, we tested the alternative hypothesis that PIs inhibit the rate of cellular proliferation. Consistent with this hypothesis, BrdU incorporation assays showed that treatment of OKF6 and CAL 27 cells with nelfinavir or lopinavir for < 24 hr caused dose-dependent reductions in the rate of DNA synthesis, with near complete inhibition in both cell lines at concentrations of 10 µM nelfinavir and 20 µM lopinavir (Fig. 4). Atazanavir, that was a less potent inhibitor of cell growth, partially inhibiting DNA synthesis at a concentration of 20 µM. Similar results were obtained with FaDu cells (data not shown). We conclude that the major mechanism by which nelfinavir and lopinavir (and possibly other PIs at higher concentrations) block growth of oral keratinocytes is by inhibition of cellular proliferation at the level of DNA synthesis.

Figure 4. HIV protease inhibitors block DNA synthesis in oral keratinocytes.

The OKF6 immortalized oral keratinocyte (A) and the CAL 27 oral carcinoma (B) cell-lines were treated with nelfinavir (Nel), lopinavir (Lop) or atazanavir (Ata) at the indicated concentrations for 20–22 hrs. BrdU was added for the last 2 hrs of PI treatment, and the rate of DNA synthesis was determined by incorporation of BrdU into total cellular DNA as described in Materials and Methods. Data were normalized to the mean level of BrdU incorporation of control (DMSO-treated) cultures, and are presented as mean +/− SEM. For OKF6 cells n = 12 for control cultures and n = 6 for PI treated cultures. For Cal27, data were pooled from 3 independent experiments; n = 36 for control cultures and n = 18 for PI treated cultures. Asterisk indicates that the mean for PI-treated cells is significantly different from the mean for control (DMSO-treated) cells (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The well documented oral and gastrointestinal adverse effects of HIV PIs14, 16, 20, 26 suggest that epithelial cell biology in the mouth and gastrointestinal tract could be compromised by the effects of these agents. In studies reported here, nelfinavir significantly inhibited the viability of primary oral keratinocytes, immortalized oral keratinocyte cell lines as well as oral squamous carcinoma cell lines at concentrations as low as 1 µM with a mean IC50 of 4.1 µM. The fact that similar reductions in cell viability were observed in normal, immortalized and carcinoma cell lines suggested that nelfinavir interferes with physiological pathways of cell growth not unique to cancer cells. Viability was also reduced with saquinavir and lopinivar. Ritonavir and atazanavir reduced cell viability minimally, whereas amprenavir and indinavir were without effect. The inhibitory effects of nelfinavir and lopinavir on cell viability were determined to be due to a block in DNA synthesis. This block occurred within 24 hrs, a time at which no evidence of cell death was detected. Importantly, the inhibitory concentrations of nelfinavir and lopinavir are well within the pharmacological range (1.23 to 7.04 µM and 8.75 to 15.3 µM, respectively) of patients undergoing standard dosing HAART.24, 25

The anti-proliferative effects of PIs on a broad spectrum of cancer cell types have been studied by several groups.2, 4–6 Nelfinavir has the most potent anti-proliferative effects with an IC50 ranging from 5.2 to 5.5 µM.4–6 We found that the mean IC50 was slightly lower (4.1 µM) in primary and immortalized oral keratinocytes and oral squamous carcinoma cell lines. Although the anti-proliferative effect of nelfinavir is due to cell death for many of the cancer cell lines studied, 4, 6 the reduction in cell viability in the oral cancer and immortalized oral epithelial cells studied here was due to a block in DNA synthesis, consistent with the ability of nelfinavir to inhibit the growth of melanoma cells through cell cycle arrest.5 These contrasting mechanisms of growth inhibition caused by nelfinavir may be due to its cell line specific effects on the cell survival PI3K-Akt signaling pathway as shown by others.2, 4, 6 Despite these differences, nelfinavir will ultimately cause cell death either directly or later as a consequence of cell cycle arrest.5

Numerous studies of the mechanisms by which PIs disrupt normal cell function have documented inhibitory effects of these drugs on Akt and NFκB activation.27 PIs have also been shown to impair proteasome function in human hepatoma cells28 and prostate carcinoma and thymoma cell lines.29,30 It is possible that these wide ranging effects on cell processes are also provoked in oral epithelial cells as a result of exposure to PIs, and that the consequences of these effects contribute to altered cell proliferation. Ongoing studies in our laboratory are investigating these possibilities.

It was reported recently that the prevalence of oral lesions in patients receiving HAART including PIs is significantly greater than those receiving HAART lacking PIs.21 Although this could be due to differences in antiviral effectiveness, it is also possible that select PIs perturb oral epithelial biology. Defects in epithelial proliferation caused by PIs could result in lesion development and/or altered healing. Our data suggest that nelfinavir and lopinavir may retard oral epithelial cell proliferation more than other PIs, and that some PIs such as indinavir or amprenavir might provide clinical advantage when wound healing is needed. In contrast, select PIs that retard growth might prove beneficial for use in conditions where epithelial growth is heightened, i.e., oral lichen planus or oral cancer. Due to the complexity of clinical trials involving HAART, animal models appear to be a logical next step.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the anti-proliferative effects of PIs on various cancer cell types extends to primary and immortalized oral epithelial cells as well as oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines and that this effect coincides with a fairly rapid cessation of DNA synthesis. It will be of great interest to determine if individual PIs have differing long-term consequences for the health of the oral cavity, as use of these drugs is commonplace in HIV infected individuals who are living longer due to antiretroviral therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: Ritonavir, Amprenavir, Lopinavir, Saquinavir, Nelfinavir, Indinavir Sulfate and Atazanavir Sulfate. This investigation was supported by Research Grant R21 DE018332 to CSM from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Badley AD. In vitro and in vivo effects of HIV protease inhibitors on apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12 Suppl 1:924–931. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow WA, Jiang C, Guan M. Anti-HIV drugs for cancer therapeutics: back to the future? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:61–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy EM, Jimenez HR, Smith SM. Current clinical treatments of AIDS. Adv Pharmacol. 2008;56:27–73. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, Shoemaker RH, Best CJ, Abu-Asab MS, et al. Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5183–5194. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang W, Mikochik PJ, Ra JH, Lei H, Flaherty KT, Winkler JD, et al. HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir inhibits growth of human melanoma cells by induction of cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1221–1227. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyrko P, Kardosh A, Wang W, Xiong W, Schonthal AH, Chen TC. HIV-1 protease inhibitors nelfinavir and atazanavir induce malignant glioma death by triggering endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10920–10928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernhard EJ, Brunner TB. Progress towards the use of HIV protease inhibitors in cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:636–637. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.5.6087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orlowski RZ, Kuhn DJ. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy: lessons from the first decade. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1649–1657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter SR, Scully C. HIV topic update: protease inhibitor therapy and oral health care. Oral Dis. 1998;4:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1998.tb00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cauda R, Tacconelli E, Tumbarello M, Morace G, De Bernardis F, Torosantucci A, et al. Role of protease inhibitors in preventing recurrent oral candidosis in patients with HIV infection: a prospective case-control study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:20–25. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arribas JR, Hernandez-Albujar S, Gonzalez-Garcia JJ, Pena JM, Gonzalez A, Canedo T, et al. Impact of protease inhibitor therapy on HIV-related oropharyngeal candidiasis. AIDS. 2000;14:979–985. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005260-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dios PD, Ocampo A, Miralles C, Limeres J, Tomas I. Changing prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus-associated oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:403–404. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.110030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton LL, McKaig R, Strauss R, Rogers D, Eron JJ., Jr Changing prevalence of oral manifestations of human immuno-deficiency virus in the era of protease inhibitor therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scully C, Diz Dios P. Orofacial effects of antiretroviral therapies. Oral Dis. 2001;7:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenspan D, Gange SJ, Phelan JA, Navazesh M, Alves ME, MacPhail LA, et al. Incidence of oral lesions in HIV-1-infected women: reduction with HAART. J Dent Res. 2004;83:145–150. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodgson TA, Greenspan D, Greenspan JS. Oral lesions of HIV disease and HAART in industrialized countries. Adv Dent Res. 2006;19:57–62. doi: 10.1177/154407370601900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leigh J. Oral warts rise dramatically with use of new agents in HIV. HIV Clin. 2000;12:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenspan D, Canchola AJ, MacPhail LA, Cheikh B, Greenspan JS. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on frequency of oral warts. Lancet. 2001;357:1411–1412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King MD, Reznik DA, O'Daniels CM, Larsen NM, Osterholt D, Blumberg HM. Human papillomavirus-associated oral warts among human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: an emerging infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:641–648. doi: 10.1086/338637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodgame JC, Pottage JC, Jr, Jablonowski H, Hardy WD, Stein A, Fischl M, et al. Amprenavir in combination with lamivudine and zidovudine versus lamivudine and zidovudine alone in HIV-1-infected antiretroviral-naive adults. Amprenavir PROAB3001 International Study Team. Antivir Ther. 2000;5:215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aquino-Garcia SI, Rivas MA, Ceballos-Salobrena A, Acosta-Gio AE, Gaitan-Cepeda LA. Short communication: oral lesions in HIV/AIDS patients undergoing HAART including efavirenz. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008;24:815–820. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickson MA, Hahn WC, Ino Y, Ronfard V, Wu JY, Weinberg RA, et al. Human keratinocytes that express hTERT and also bypass a p16(INK4a)-enforced mechanism that limits life span become immortal yet retain normal growth and differentiation characteristics. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1436–1447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1436-1447.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piboonniyom SO, Duensing S, Swilling NW, Hasskarl J, Hinds PW, Munger K. Abrogation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor checkpoint during keratinocyte immortalization is not sufficient for induction of centrosome-mediated genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2003;63:476–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acosta EP, Gerber JG. Position paper on therapeutic drug monitoring of antiretroviral agents. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2002;18:825–834. doi: 10.1089/08892220260190290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Justesen US. Therapeutic drug monitoring and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antiretroviral therapy. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:20–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roca B. Adverse drug reactions to antiretroviral medication. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1785–1792. doi: 10.2741/3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein WB, Dennis PA. Repositioning HIV protease inhibitors as cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2008;3:666–675. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328313915d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamel FG, Fawcett J, Tsui BT, Bennett RG, Duckworth WC. Effect of nelfinavir on insulin metabolism, proteasome activity and protein degradation in HepG2 cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2005.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaedicke S, Firat-Geier E, Constantiniu O, Lucchiari-Hartz M, Freudenberg M, Galanos C, et al. Antitumor effect of the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor ritonavir: induction of tumor-cell apoptosis associated with perturbation of proteasomal proteolysis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6901–6908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pajonk F, Himmelsbach J, Riess K, Sommer A, McBride WH. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 protease inhibitor saquinavir inhibits proteasome function and causes apoptosis and radiosensitization in non-HIV-associated human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5230–5235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]