Abstract

Motivation: RNA-Seq is a promising new technology for accurately measuring gene expression levels. Expression estimation with RNA-Seq requires the mapping of relatively short sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcript set. Because reads are generally shorter than transcripts from which they are derived, a single read may map to multiple genes and isoforms, complicating expression analyses. Previous computational methods either discard reads that map to multiple locations or allocate them to genes heuristically.

Results: We present a generative statistical model and associated inference methods that handle read mapping uncertainty in a principled manner. Through simulations parameterized by real RNA-Seq data, we show that our method is more accurate than previous methods. Our improved accuracy is the result of handling read mapping uncertainty with a statistical model and the estimation of gene expression levels as the sum of isoform expression levels. Unlike previous methods, our method is capable of modeling non-uniform read distributions. Simulations with our method indicate that a read length of 20–25 bases is optimal for gene-level expression estimation from mouse and maize RNA-Seq data when sequencing throughput is fixed.

Availability: An initial C++ implementation of our method that was used for the results presented in this article is available at http://deweylab.biostat.wisc.edu/rsem.

Contact: cdewey@biostat.wisc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics on

1 INTRODUCTION

Taking advantage of rapidly advancing sequencing technology, researchers are now using high-throughput sequencers to measure gene expression with a protocol called RNA-Seq (Nagalakshmi et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). RNA-Seq is the transcriptome analog to whole-genome shotgun sequencing (Staden, 1979), with a key difference being that RNA-Seq is primarily used for estimating the copy number of transcripts in a sample. The main steps in the protocol are (i) RNA is isolated from a sample, (ii) RNA is converted to cDNA fragments via reverse-transcription and fragmentation, (iii) a high-throughput sequencer [such as those from Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA), Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA) and Roche 454 Life Science (Branford, CT, USA)] is used to generate millions of reads from the cDNA fragments, (iv) reads are mapped to a reference genome or transcript set with an alignment tool and (v) counts of reads mapped to each gene are used to estimate expression levels. Because the primary outputs of RNA-Seq are counts of reads, they are referred to as ‘digital’ gene expression measurements, as opposed to the ‘analog’ fluorescence intensities from microarrays.

RNA-Seq is a promising replacement for microarrays as initial studies have shown that RNA-Seq expression estimates are highly reproducible (Marioni et al., 2008) and often more accurate, based on quantitative PCR (qPCR) and spike-in experiments (Mortazavi et al., 2008; Nagalakshmi et al., 2008). Although still a young technology, RNA-Seq has matured enough to be used in studies of transcription in yeast (Nagalakshmi et al., 2008), Arabidopsis (Lister et al., 2008), mouse (Cloonan et al., 2008; Mortazavi et al., 2008), and human (Marioni et al., 2008; Morin et al., 2008). The primary advantages of RNA-Seq are its large dynamic range (spanning five orders of magnitude), low background noise, requirement of less sample RNA and ability to detect novel transcripts, even in the absence of a sequenced genome (Wang et al., 2009). To allow the technology to reach its full potential, a number of experimental and computational challenges need to be addressed, including the handling of read mapping uncertainty, sequencing non-uniformity, estimation of potentially novel isoform (alternatively spliced transcript) expression levels and efficient storage and alignment of RNA-Seq reads.

In this article, we present our work in addressing the computational issue of read mapping uncertainty. Because RNA-Seq reads do not span entire transcripts, the transcripts from which they are derived are not always uniquely determined. Paralogous gene families, low-complexity sequence and high sequence similarity between alternatively spliced isoforms of the same gene are primary factors contributing to mapping uncertainty. In addition, polymorphisms, reference sequence errors and sequencing errors require that mismatches and indels be allowed in read alignments and further contribute to lower our confidence in mappings. Due to these factors, a significant number of reads are multireads: reads that have high-scoring alignments to multiple positions in a reference genome or transcript set (Mortazavi et al., 2008). We will refer to reads that map to multiple genes as gene multireads and reads that map to a single gene but multiple isoforms as isoform multireads. The fraction of mappable reads that are gene multireads varies and depends on the transcriptome and read length. For the datasets we analyzed, this fraction ranged between 17% (mouse) and 52% (maize), representing a significant proportion of RNA-Seq data.

Two strategies have been previously used for handling gene multireads. The first simply discards them, keeping only uniquely mapping reads for expression estimation (Marioni et al., 2008; Nagalakshmi et al., 2008). A slightly more sophisticated method using only uniquely mapping reads adjusts exon coverage by the fraction of exon positions that would give rise to uniquely mapping reads (Morin et al., 2008). A second strategy has been to ‘rescue’ multireads by allocating fractions of them to genes in proportion to coverage by uniquely mapping reads (Faulkner et al., 2008; Mortazavi et al., 2008). These rescue strategies have been shown to give expression estimates that are in better agreement with microarrays than those from only using uniquely mapping reads (Mortazavi et al., 2008). A more recent method handles isoform multireads by explicitly estimating isoform expression levels but does not handle gene multireads (Jiang and Wong, 2009).

We present a method for estimating expression in the presence of multireads that treats mapping uncertainty in a statistically rigorous manner. Using a generative model of RNA-Seq data, we unify the notions of gene and isoform multireads through latent random variables representing the true mappings. Model parameters correspond to isoform expression levels, read distributions across transcripts and sequencing error. We estimate maximum likelihood (ML) expression levels using an Expectation–Maximization (EM) algorithm and show that previous rescue methods are roughly equivalent to one iteration of EM. Our inference method can be thought of as the RNA-Seq analog of methods for correcting for SAGE sequencing errors (Beissbarth et al., 2004) and microarray cross-hybridization (Kapur et al., 2008).

Like the statistical method of Jiang and Wong (2009), our model can be used to estimate individual isoform expression levels. In contrast with their method, our method incorporates gene multireads into a statistical model and does not require knowledge of which isoforms share exonic sequence. In addition, our model can accommodate non-uniform read distributions across transcripts (e.g. 3′ biases), which may be simultaneously learned from the data.

Results from simulations with parameters derived from real data indicate that our method gives more accurate gene expression estimates than those using only unique reads or rescue strategies. We show that estimation of gene expression levels as the sum of estimated isoform expression levels improves gene-level accuracy. We found a slight 3′ bias in the read distributions of a real dataset and determined that taking such non-uniformities into account can improve accuracy, depending on the strength of the bias. Last, through simulations with varying read lengths, we show that the optimal length for RNA-Seq is around 20–25 bases for the mouse and maize transcriptomes when our method is used to handle multireads.

1.1 Problem statement

The goal of expression analysis is to estimate a transcriptome: the set of all expressed transcripts and their frequencies in a cell at a given time. By itself, RNA-Seq data allow us to estimate the relative expression levels of isoforms in a sample. Combined with accurate physical sample size or spike-in measurements, absolute expression may be estimated (Mortazavi et al., 2008), but that is a separate issue that we will not discuss here.

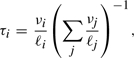

There are two natural measures of relative expression: the fraction of transcripts and the fraction of nucleotides of the transcriptome made up by a given gene or isoform. For isoform i, we will denote these two quantities by τi and νi, respectively. At the isoform level, these quantities are related by the equations

| (1) |

|

(2) |

where ℓi is the length, in nucleotides, of isoform i. At the gene level, expression is simply the sum of the expression of possible isoforms. For ease of notation, we give expression levels in terms of nucleotides per million (NPM) and transcripts per million (TPM), which are obtained by multiplying ν and τ by 106, respectively.

The problem addressed in this article is that of using a set of RNA-Seq data to estimate the ν and τ values for a set of previously identified isoforms and genes. We assume that the RNA-Seq data comes in the form of N sequence reads, each of length L. Reference sequences, but not necessarily genomic coordinates, are assumed to be available for all M isoforms. Sequence clustering or genomic coordinates may be used to group isoforms into genes, if desired.

The fundamental assumption of RNA-Seq is that the fraction of reads derived from isoform i is a function of νi. Assuming uniformly distributed reads, all of which can be assigned to isoforms, and poly(A)+mRNA, we have that ci/N approaches νi as N→∞, where ci is the number of reads from isoform i. Even if reads are not uniformly distributed along the lengths of isoforms, so long as they are sampled in proportion to νi, this result still holds.

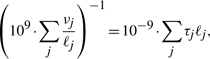

1.1.1 Comparison to RPKM estimation

We compare the problem of estimating ν and τ values with that of computing expression in terms of reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM; Mortazavi et al., 2008). The measured level of isoform i, in RPKM, is defined as 109 × ci/(Nmℓi), where ci is the number of reads mapping to isoform i, Nm is the total number of mappable reads and ℓi is the length of isoform i. Under the assumption of uniformly distributed reads, we note that RPKM measures are estimates of 109 × νi/ℓi, which is an unnormalized value of τi. The normalization factor is

|

which is proportional to the mean length of a transcript in the transcriptome. When the mean expressed transcript length is 1 kb, 1 TPM is equivalent to 1 RPKM, which corresponds to roughly one transcript per cell in mouse (Mortazavi et al., 2008).

Because the mean expressed transcript length may vary between samples, we prefer the use of ν and τ over RPKM measures. For example, an isoform with the same fraction of transcripts in two samples will have different RPKM values if the expression of other genes changes such that the mean expressed transcript length differs. In addition, τ values are comparable between two species even if mRNA lengths tend to be larger in one of the species.

2 METHODS

2.1 Generative model

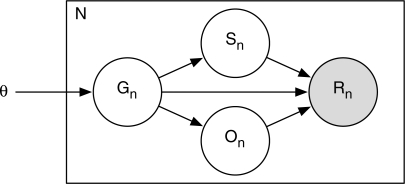

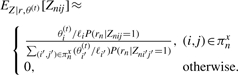

We estimate gene and isoform expression levels with a generative model of the RNA-Seq read sequencing process. We use the directed graphical model (Bayesian network) shown in Figure 1. The model generates N i.i.d. reads of length L. The read sequences are represented by the Rn random variables and are the observed data. Each read is associated with three latent random variables, Gn, Sn and On, which represent the isoform, start position and orientation, respectively, from which the read was derived. The primary parameters of the model are θ=[θ0,…, θM], which correspond to the expression levels. The complete data likelihood for this model is

Fig. 1.

The graphical model for RNA-Seq data used by our method.

We assume that we are given all M isoforms that may be present in a transcriptome. The random variable Gn takes a value in [0, M], with the value 0 representing a ‘noise’ isoform, which generates reads that do not map to known isoforms. We let P(Gn=i|θ)=θi, where ∑iθi=1.

The random variable Sn takes a value in [1, maxiℓi], where ℓi is the length of isoform i. We call P(Sn=j|Gn=i) the read start position distribution (RSPD). Assuming that reads are generated uniformly across transcripts, P(Sn=j|Gn=i)=ℓi−1. Here, we are also assuming that mRNAs have poly(A) tails, which allow for reads to start at the last positions of isoforms and extend into the poly(A) tails. For poly(A)- mRNA samples, the RSPD becomes P(Sn=j|Gn=i)=(ℓi−L+1)−1. We present a non-uniform RSPD model in a following section.

The random variable On is binary, with On=0 indicating that the sequence of read n is in the same orientation as that of its parent isoform, and On=1 indicating that it is reverse complemented. This random variable allows us to model RNA-Seq protocols that are not strand-specific, such as the one used in Mortazavi et al. (2008). For such protocols, we set P(On=0|Gn≠0)=0.5. For strand-specific protocols, we may simply set P(On=0|Gn≠0)=1.

The observed data of the model are the read sequences, which we represent by the Rn random variables. For simplicity of notation, we summarize the hidden random variables for the n-th read with a set of indicator random variables Znijk, where Znijk=1 if (Gn, Sn, On)=(i, j, k). When the protocol is strand-specific, we use variables Znij=Znij0. The conditional probability of a read sequence derived from isoform i>0 is given by

where γi is the sequence of isoform i,  is its reverse complement and wt(a, b) is a position-specific substitution matrix. The value of wt(a, b) is the probability that we observe character a at position t of the read given that the corresponding character in the reference isoform sequence is b. The conditional probability distributions given by the w matrices allow us to model read position and base-dependent substitution processes. For example, base-call errors are often more frequent in the last positions of a read, and thus wL may give a higher substitution probability than w1. In addition to sequencing error, factors such as polymorphism and reference sequence error may lead to observed substitutions between an isoform sequence and a derived read. Our current model does not distinguish between these processes and summarizes their effects through the w matrices.

is its reverse complement and wt(a, b) is a position-specific substitution matrix. The value of wt(a, b) is the probability that we observe character a at position t of the read given that the corresponding character in the reference isoform sequence is b. The conditional probability distributions given by the w matrices allow us to model read position and base-dependent substitution processes. For example, base-call errors are often more frequent in the last positions of a read, and thus wL may give a higher substitution probability than w1. In addition to sequencing error, factors such as polymorphism and reference sequence error may lead to observed substitutions between an isoform sequence and a derived read. Our current model does not distinguish between these processes and summarizes their effects through the w matrices.

Reads derived from the ‘noise’ isoform (i=0) are generated from a position-independent background distribution, β, with

The random variables Sn and On are irrelevant when Gn=0, and thus we set P(On=0|Gn=0)=1, P(Sn=1|Gn=0)=1 and ℓ0=1.

2.1.1 Non-uniform RSPDs

The distributions of read start positions are often non-uniform (Wang et al., 2009). Such non-uniformity may be due to a variety of factors, including fragmentation protocols and composition biases (Dohm et al., 2008). To take these non-uniformities into account, we allow the use of an empirical RSPD in our model. Currently, we use a RSPD that depends on the fraction along an isoform's length of a given start position. Specifically, we use

where ecdfRSPD is an empirical cumulative density function over [0, 1], represented as a piecewise linear function with B parameters, ϕ=ϕ1…ϕB. We use one RSPD for all isoforms, as there is often not enough data to estimate these distributions for individual isoforms. This scheme allows us to model general phenomena, such as 5′ or 3′ biases, but does not take into account isoform-specific effects (e.g. sequence composition).

2.2 Inference with the EM algorithm

For isoform expression-level estimation, we are interested in inferring the values of the model parameters θ=[θ0, θ1,…, θM]. Under the assumption that reads are uniformly sampled from the transcriptome, these parameters correspond to relative expression levels. With this assumption, we estimate νi by  and use Equation (2) for converting to τi.

and use Equation (2) for converting to τi.

Given RNA-Seq data, we estimate expression levels by finding the values of θ that maximize the observed data likelihood:

| (3) |

Equation (3) shows that our goal is to find the ML proportions of a mixture model. We use the EM algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) to find the ML values for θ. We assume that all other parameters of the model, i.e. those involved in P(rn|Gn=i) are either fixed or estimated ahead of time. For fixed P(rn|Gn=i), the observed data likelihood [Equation (3)] is concave (see Supplementary Material), and thus the EM algorithm is guaranteed to find ML values. However, even with infinite data, it is possible for the parameters to be non-identifiable, depending on the structural relationships between isoforms (Lacroix et al., 2008). Such a case would correspond to a plateau in the likelihood surface.

The implementation of the EM algorithm for our model is straightforward and the details are given in the Supplementary Material. A key aspect of the algorithm is the E-step: the computation of the expected values of the Znij (or Znijk) random variables, given the current parameter values, θ(t). For a uniform RSPD and a strand-specific protocol, this computation is

| (4) |

2.2.1 Approximation via read alignment

Due to the large number of reads, isoforms and read start positions, it is not practical to compute expected values for all Znij. Thus, we approximate the likelihood function by only allowing a small number of the Znij variables to be non-zero. To determine which variables to consider, we align the reads to the isoform sequences and keep all alignments with at most x mismatches. Letting πxn denote the set of all (i, j) pairs for alignments of read n with at most x mismatches, and the noise pair (0, 1), we approximate the likelihood function by

Equation (4) is similarly approximated by

|

(5) |

Noting that θ(t)i/ℓi is proportional to the RPKM of isoform i, we observe that Equation (5) is roughly equivalent to the rescue scheme of Mortazavi et al. (2008) when a read is considered to align equally well to all candidate positions in πn and the noise isoform is not considered. Thus, the rescue scheme can be thought of as a single iteration of the EM algorithm with initial parameters, θ(0), derived from only uniquely mapping reads.

To speed up computations, we also filter reads that align to a large number of positions and adjust our θ estimates to account for these discarded alignments (see Supplementary Material).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Simulation experiments

In the absence of RNA-Seq data from samples for which we know all true mRNA quantities, we performed simulations to validate our method and assess its performance with respect to other RNA-Seq expression-level estimators. We used our generative model to simulate reads from two reference transcript sets, one from mouse and the other from maize. The estimates from our method, as well as those from two other methods, were compared with the sample expression values in each simulation.

3.1.1 Methods for comparison

We compared the gene expression-level estimates of our method with those of two previously used methods for handling multireads. Neither of these prior methods is capable of estimating isoform expression levels, and thus we compared only gene expression estimates. The first and simplest method, unique, estimates expression solely from uniquely mapping reads. A read is considered to be uniquely mapped if it only aligns to isoforms of a single gene. This method computes expression levels as

| (6) |

where ciuni is the number of uniquely mapping reads that map to gene i and cuni is the total number of uniquely mapping reads. The transcript fractions are then computed by

|

(7) |

where  is the effective length of gene i. For genes with a single isoform,

is the effective length of gene i. For genes with a single isoform,  is simply the length of that isoform. For alternatively spliced genes, we take

is simply the length of that isoform. For alternatively spliced genes, we take  to be the length of the union of all genomic intervals corresponding to exons of isoforms of gene i, as is done in the ERANGE software package (Mortazavi et al., 2008).

to be the length of the union of all genomic intervals corresponding to exons of isoforms of gene i, as is done in the ERANGE software package (Mortazavi et al., 2008).

A second method, which we call rescue, allocates multireads to genes in proportion to the τiuni values. This method was introduced in Mortazavi et al. (2008) and is currently used in the ERANGE software package, as well as in the RSAT package (Jiang and Wong, 2009). The rescue method computes the count for gene i as

| (8) |

where πn is the set of indices of genes to which read n maps. A multiread that maps only to genes for which τuni=0 is divided evenly among those genes. The values of νirescue and τirescue are then calculated similarly to Equations (6) and (7).

3.1.2 Simulation procedure

We first derived simulation parameters from the mouse liver RNA-Seq data described in Mortazavi et al. (2008). Nucleotide fractions (ν) were computed from this data with the rescue method (so as to reduce the bias toward our method) and the mouse UCSC Genes (Hsu et al., 2006) as the reference gene set. For genes with multiple isoforms, these fractions were divided randomly amongst the isoforms. We estimated position-specific substitution matrices (wt) from uniquely mapping reads and a ‘noise’ read model (β) from unmappable reads, which made up 46.2% of the data. We obtained read mappings by running the Bowtie aligner (Langmead et al., 2009) with at most two mismatches allowed. Using these parameters, a uniform RSPD and a non-strand-specific model, we simulated 30 million reads of length 25 from the mouse reference gene set with our generative model.

An additional simulation set with the same size and read length was generated from a maize gene set. We chose maize to assess how variations in genome repetitiveness affect expression estimation. The maize gene set used was release 3b.50 of the working gene set obtained from http://maizesequence.org, with duplicate mRNAs removed. Expression levels for each maize gene were sampled, with replacement, from the mouse liver gene expression estimates.

We mapped simulated reads with Bowtie, allowing at most two mismatches per alignment. Table 1 summarizes the read mapping results on the real and simulated datasets. Gene multireads made up 17% and 52% of mappable reads in the mouse and maize datasets, respectively. The distribution of the numbers of genes and isoforms to which the reads mapped are shown in Supplementary Figure 6.

Table 1.

Fractions of reads that are unmappable, map uniquely, map to multiple genes or are filtered in three RNA-Seq datasets

| Dataset | % unmapped | % unique | % multi | % filtered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Real | 46.2 | 44.4 | 9.2 | 0.2 |

| Mouse Sim | 47.6 | 43.2 | 8.7 | 0.6 |

| Maize Sim | 47.5 | 25.0 | 27.1 | 0.4 |

3.1.3 Simulation results

The unique, rescue and em methods were run with the same set of alignments as input to estimate gene expression levels. Estimates were compared with the sample values, i.e. the expression estimates given the true counts of sample reads derived from each isoform [via Equations (6) and (2) with the true read counts]. We compare with the sample values instead of the model parameters because the sample values are the best estimates one could make if all latent variables were observed. Comparisons with the model parameters are affected by sampling error, which affects all methods equally and obscures the differences between them.

We used two measures of error of the expression estimates. First, as a general measure of accuracy that is robust to outliers, we computed the median percent error (MPE) with respect to the sample values. Second, we computed the fraction of genes for which the estimates were significantly different (percent error > 5%) from the sample values. We refer to this second statistic as the error fraction (EF). For these two measures, we only consider genes with sample ν or τ no less than 1 NPM or 1 TPM, respectively. We additionally calculate a false positive rate, which is the fraction of genes with sample τ below 1 TPM that are estimated to have τ at least 1 TPM. Table 2 gives the MPE and EF statistics for estimates on the mouse and maize simulated data. Scatter plots of estimates versus sample values are given in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Error of the unique, rescue and em estimated gene expression levels with respect to sample expression values from simulations of mouse and maize RNA-Seq data

| Sample gene expression in NPM (ν) or TPM (τ) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [1, 10) | [10, 102) | [102, 103) | [103, 104) | [104, 105) | All | |||

| Simulation of mouse RNA-Seq data | ||||||||

| N | 5577 | 5240 | 1028 | 114 | 9 | 11968 | ||

| MPE | unique | 18.9 | 18.7 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 20.7 | 18.8 | |

| rescue | 2.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.6 | ||

| ν | em | 2.3 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | |

| EF | unique | 93.9 | 96.2 | 96.5 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 95.2 | |

| rescue | 26.9 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 7.9 | 33.3 | 15.9 | ||

| em | 18.8 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.7 | ||

| N | 6279 | 4025 | 886 | 111 | 15 | 11316 | ||

| MPE | unique | 29.6 | 29.2 | 30.9 | 32.8 | 32.1 | 29.6 | |

| rescue | 12.6 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 8.2 | ||

| τ | em | 2.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.5 | |

| EF | unique | 93.7 | 93.9 | 95.6 | 99.1 | 100.0 | 94.0 | |

| rescue | 79.5 | 73.2 | 72.2 | 69.4 | 66.7 | 76.6 | ||

| em | 27.8 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.7 | ||

| Simulation of maize RNA-Seq data | ||||||||

| N | 8934 | 4737 | 988 | 119 | 14 | 14792 | ||

| MPE | unique | 86.8 | 87.8 | 88.7 | 88.1 | 85.9 | 87.3 | |

| rescue | 11.3 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 6.6 | ||

| ν | em | 3.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 2.3 | |

| EF | unique | 97.3 | 97.3 | 97.5 | 93.3 | 100.0 | 97.3 | |

| rescue | 65.8 | 42.6 | 22.7 | 11.8 | 7.1 | 55.0 | ||

| em | 40.5 | 16.5 | 6.4 | 2.5 | 21.4 | 30.2 | ||

| N | 9210 | 4931 | 1040 | 113 | 12 | 15306 | ||

| MPE | unique | 86.1 | 84.2 | 85.2 | 80.5 | 96.3 | 85.5 | |

| rescue | 21.3 | 11.8 | 8.9 | 8.5 | 7.7 | 16.0 | ||

| τ | em | 4.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 2.8 | |

| EF | unique | 97.2 | 96.7 | 97.1 | 98.2 | 100.0 | 97.0 | |

| rescue | 89.4 | 88.3 | 85.8 | 82.3 | 91.7 | 88.8 | ||

| em | 47.5 | 18.8 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 16.7 | 35.1 | ||

Error measures are given for genes at different levels of expression, as well as for all genes with expression at least 1 NPM (ν) or 1 TPM (τ). Bold values indicate that the estimates are significantly (P<0.05) more accurate, as assessed by a paired Wilcoxon signed rank test. In all but one category, em is significantly more accurate than the others. For the highly expressed category (104−105 NPM) in maize, em actually performs slightly worse in terms of ν EF than rescue. We attribute this oddity to a couple of repetitive genes within the small number of genes (14) in this category.

For mouse, the rescue and em methods both estimate ν to within a few percent for most genes, with the em estimates being generally more accurate (paired Wilcoxon signed rank test, P=7.2 × 10−273). The unique method gives much poorer estimates, with an overall MPE of 18.8% and an EF of 95.2%. The accuracies of rescue and em are highest for genes with high expression as more data are available to allocate multireads for these genes. The EF statistic shows a greater difference in the accuracy of the methods, with em producing the smallest number of outlier estimates (overall ν EF of 9.7%, compared with 15.9% for rescue). Even larger differences between the methods are seen with respect to τ estimates. This difference is largely due to the fact that rescue does not estimate individual isoform expression levels and instead uses a single ‘effective’ length in order to calculate τ. Lastly, the false positive rates for the unique, rescue and em methods on the mouse data were 1.8%, 0.97% and 0.89%, respectively.

For the maize dataset, extensive recent gene paralogy makes RNA-Seq analysis challenging, as uniquely mapping reads are in the minority of all mappable reads. Nevertheless, the overall ν MPE for em estimates on this set is 2.3%, as compared with 6.6% for rescue estimates. The EF for ν estimates is much higher than in mouse, however, with values of 30.2% and 55.0% for em and rescue, respectively. The false positive rates on the maize dataset are also much higher, with the unique, rescue and em methods giving false positive rates of 4.2%, 7.7% and 4.4%, respectively.

3.2 Non-uniform RSPDs

We explored the uniformity of RSPDs in RNA-Seq data and analyzed how using a non-uniform model affects the accuracy of expression estimates. First, we learned an RSPD (B=10000) from the mouse liver dataset (Supplementary Fig. 3). Our learned RSPD indicates a 3′ bias in the RNA-Seq protocol used in Mortazavi et al. (2008), despite attempts by the generators of this data to eliminate such biases through alternative fragmentation methods.

We then simulated a set of reads from the mouse and maize reference gene set, as in the previous section, but with our estimated non-uniform RSPD. A model assuming a uniform RSPD (em uniform) and a model that learns a RSPD (em rspd) were used to estimate expression levels from this dataset. Although the ν and τ estimates from the two models were similar, em rspd estimates were generally more accurate (Supplementary Table 1). An additional set of experiments in mouse and maize with a more extreme 3′-biased RSPD (Supplementary Fig. 4) further differentiated the two models (Supplementary Table 2). These results indicate that incorporating a non-uniform RSPD into a RNA-Seq model helps to increase accuracy, although the benefits of the more sophisticated model are only noticeable when the RSPD is highly non-uniform.

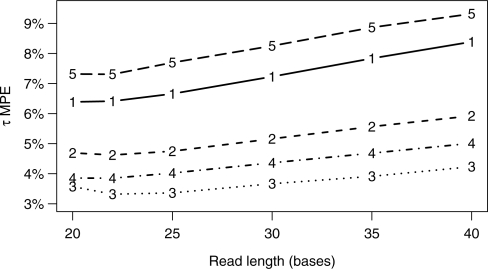

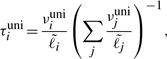

3.3 Determination of optimal read length

Sequencing technologies vary in the number and lengths of reads they can produce. Assuming an economic model in which the cost of RNA-Seq is proportional to the number of bases sequenced, we wished to determine the read length that allows for the highest accuracy in expression estimation. Given a fixed throughput, one can produce a large number of short reads or a smaller number of long reads. Longer reads reduce estimation error due to mapping uncertainty, whereas a larger number of reads reduces error due to sampling. The optimal read length achieves a balance between these two sources of error.

We performed simulations with fixed throughput and varying read lengths to analyze this trade-off. To assess differences across species and tissues, we simulated from the mouse liver, mouse brain and maize transcriptomes. As for the mouse liver simulation, parameters for the mouse brain simulation were determined from data from Mortazavi et al. (2008). We fixed the throughput at 750 million bases (roughly that of the mouse liver data) and generated read sets with lengths ranging from 20 to 40 bases. Given this fixed throughput, the number of reads in each set ranged from 18.75 million (L=40) to 37.5 million (L=20). For mouse liver, we performed additional experiments with twice the throughput (1.5 billion) and half the throughput (375 million) as the other three experiments. Reads were simulated according to the expression-level parameters of the corresponding tissue and species and with a position-independent error rate of 1%. The maximum number of mismatches allowed in alignments was one for L≤22 and two for longer reads. Five simulations were run for each read length and expression levels were estimated using our method. Figure 2 shows the mean τ MPE for the estimates on these sets. The trends are identical for the ν and EF measures (data not shown). Our results indicate that a read length between 20 and 25 bases gives the highest accuracy for the transcriptomes and throughputs considered.

Fig. 2.

Gene expression estimation accuracy varies with read length given fixed base throughput (T). The curves are (1) mouse liver, T=375 × 106, (2) mouse liver, T=750 × 106, (3) mouse liver, T=1.5 × 107, (4) mouse brain, T=750 × 106 and (5) maize, T=750 × 106. The τ MPE was calculated with respect to the true expression values for all genes with true level at least 1 TPM.

3.4 Estimation on mouse liver data

We reanalyzed the mouse liver dataset using our method and have made the results available on our method's web site. To assess the variance in the expression estimates produced by our method, we computed standard error estimates for each gene using the non-parametric bootstrap technique. As expected for a multinomial model, the variance of the ν estimates are roughly proportional to their means (Supplementary Fig. 5).

4 DISCUSSION

In this article, we have shown that a statistical model for RNA-Seq can be used to address read mapping uncertainty, and therefore, to produce more accurate gene expression estimates than simpler methods. Through simulations that closely modeled real data, we confirmed that our method improved accuracy for experiments in both mouse and maize. The improvement in accuracy is most striking for repetitive genomes, such as maize, which give rise to large fractions of multireads. In addition, our results on τ estimation accuracy show that estimating individual isoform expression levels is critical to calculating gene-level estimates in terms of fractions of transcripts.

We chose to focus on gene-level accuracy as our preliminary work has indicated that isoform-level estimation is only feasible for the most highly expressed genes with current read throughputs. When gene multireads are negligible, we expect our isoform estimates to be comparable with those produced by the method of Jiang and Wong (2009), as it is based on a similar model. When gene multireads are significant, we have shown that our method gives better gene-level accuracy than the rescue method, which is used in Jiang and Wong (2009) for allocating gene multireads.

Our optimal read length results may have significant implications for future RNA-Seq analyses. We show that given a fixed sequencer throughput, the optimal read length for gene expression estimation from RNA-Seq experiments on organisms with known genomes is surprisingly short. We determined this length to be between 20 and 25 bases for the transcriptomes of maize and two mouse tissues. This result suggests that sequencing technology developers should strive for larger numbers of reads rather than longer reads when the target application is gene expression. Longer reads certainly help to reduce mapping uncertainty, but with methods that can handle this uncertainty, greater accuracy is achieved with a larger number of short reads. Researchers performing RNA-Seq experiments should generally use the full length of the reads produced by their sequencer kits, but if given the choice between kits that trade read length for read quantity, they should opt for the one that produces more reads.

Our optimal read length result depends on the assumptions that (i) all possible isoforms in a transcriptome are known, (ii) only gene-level expression estimates are needed and (iii) accuracy across all genes is the primary objective, rather than accuracy on a specific subset. When these assumptions do not hold, longer reads may be beneficial. In addition, the optimal read length is likely to be dependent on the target species and throughput and thus additional experiments should be done for other conditions to determine appropriate read lengths.

Although our accuracy results are based on simulations, we believe they are a fair test of expression estimation methods as the simulations are of RNA-Seq data that follow standard assumptions. The primary assumption of the simulations is that reads are generated uniformly across the transcriptome, or at least in proportion to νi for each isoform (in the case of non-uniformity across a transcript's length). All current methods, including our own, rely on this assumption. One alternative to simulation would have been to compare to microarray estimates, as has been done to validate RNA-Seq technology in general (Marioni et al., 2008; Mortazavi et al., 2008). However, microarray estimates cannot be considered to be the ground truth and, in fact, offer less precision than those from RNA-Seq (Wang et al., 2009). Ideally, we would assess accuracy using an RNA-Seq dataset for which isoform levels have been determined via qPCR, but such a dataset is difficult to obtain due to the relatively low-throughput nature of qPCR.

As our primary motivation has been read mapping uncertainty, the usefulness of our method is dependent on the number of multireads in an RNA-Seq dataset. With sequencers producing longer read lengths each year, one might expect the number of multireads to drop significantly. However, there are several reasons why multireads will remain relevant until reads span entire RNA molecules. First, longer and paired-end reads do not decrease the number of multireads by as much as one might expect. Our simulations with 75 base reads and paired-end 75 base reads (200 base insert) on the mouse transcriptome give rise to 10% and 8% gene multireads, respectively. These are still significant fractions compared with 17% multireads for 25 base reads. Second, our results suggest that the best sequencers for RNA-Seq should produce large numbers of short reads (20–25 bases), in which case multireads are highly relevant. Third, isoform multireads are prominent even for long read lengths as alternate isoforms often share a significant fraction of their sequence. Since accurate expression estimation depends on identifying expression of individual isoforms, correctly handling isoform multireads will remain an important issue.

Our future work will include a number of refinements to more closely model the RNA-Seq read generation process. For example, we will extend the model to incorporate sequencer quality scores, paired-end reads, variable read lengths (such as in 454 data), and allow for indels in reads. Other non-uniformities of RNA-Seq data, such as biases toward certain base compositions (Dohm et al., 2008), will also be addressed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank members of the Thomson lab for helpful discussions regarding RNA-Seq protocols. We also acknowledge Ali Mortazavi for help in analyzing the data from Mortazavi et al. (2008). Lastly, we thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the initial version of this article.

Funding: MacArthur Professorship funds (to J.T. and in part to B.L.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Beissbarth T, et al. Statistical modeling of sequencing errors in SAGE libraries. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(Suppl. 1):i31–i39. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan N, et al. Stem cell transcriptome profiling via massive-scale mRNA sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:613–619. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, et al. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dohm JC, et al. Substantial biases in ultra-short read data sets from high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner GJ, et al. A rescue strategy for multimapping short sequence tags refines surveys of transcriptional activity by CAGE. Genomics. 2008;91:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F, et al. The UCSC known genes. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1036–1046. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Wong WH. Statistical inferences for isoform expression in RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1026–1032. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur K, et al. Cross-hybridization modeling on Affymetrix exon arrays. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2887–2893. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix V, et al. Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Algorithms in Bioinformatics. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2008. Exact transcriptome reconstruction from short sequence reads; pp. 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, et al. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, et al. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni JC, et al. RNA-seq: An assessment of technical reproducibility and comparison with gene expression arrays. Genome Res. 2008;18:1509–1517. doi: 10.1101/gr.079558.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin RD, et al. Profiling the HeLa S3 transcriptome using randomly primed cDNA and massively parallel short-read sequencing. BioTechniques. 2008;45:81–94. doi: 10.2144/000112900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagalakshmi U, et al. The transcriptional landscape of the yeast genome defined by RNA sequencing. Science. 2008;320:1344–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.1158441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staden R. A strategy of DNA sequencing employing computer programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;6:2601–2610. doi: 10.1093/nar/6.7.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, et al. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.