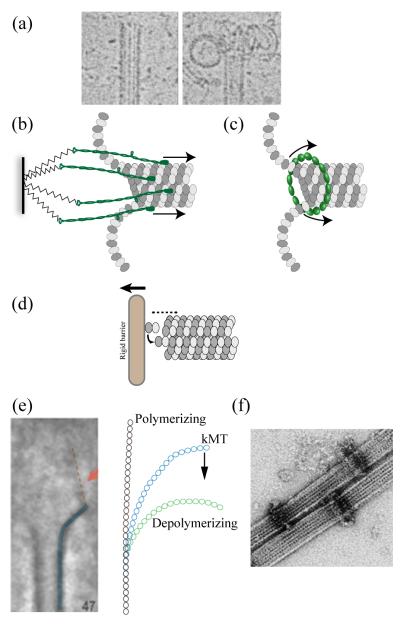

Figure 1.

(a) Morphology of polymerizing and depolymerizing MT plus-ends in vitro. Disassembling MT plus-ends allow two mechanisms of force generation coupled to the disassembly. (b) Biased diffusion models - proteins weakly bound to the MT lattice diffuse along the lattice in the absence of external force. However, the shortening plus-end acts as a moving boundary and biases the diffusive movement towards the minus end. (c) Forced walk models – A ring around the lattice serves as a barrier to the relaxation of curling protofilaments. Continuous outwards curling pushes the ring towards the minus end. (d) A plus-end growing against a rigid barrier generates force by thermal ratchet mechanism. Two types of forced walk couplers based on EM and in vitro data have been proposed (e and f). (e) Morphology of kMT plus-ends observed in ultrathin sections. Averaging over many protofilaments reveals the presence of fibrillar structures (orange) of unknown identity that bind on the inside of the curling protofilament (blue). kMT protofilaments (blue) display an intermediate curvature that may be indicative of incomplete relaxation of strain. If the fibrils bound to each protofilament are responsible for this curvature, then they can convert the strain into a minus-end directed force. (f) Dam1/DASH rings in vitro act as force couplers that convert the strain energy efficiently into a pushing force or work.