Abstract

Objective

To determine whether pentoxifylline 400 mg (Trental 400) taken orally three times daily, in addition to ambulatory compression bandages and dressings, improves the healing rate of pure venous ulcers.

Design

Randomised, double blind placebo controlled trial, parallel group study of factorial design, permitting the simultaneous evaluation of alternative pharmaceutical, bandaging, and dressings materials.

Setting

Leg ulcer clinics of a teaching and a district general hospital in southern Scotland.

Participants

200 patients with confirmed venous ulcers and in whom other major causal factors were excluded.

Interventions

Pentoxifylline 400 mg three times daily or placebo.

Main outcome measure

Complete healing (full epithelialisation) of all ulcers on the trial leg.

Results

Complete healing occurred in 65 of the 101 (64%) patients receiving pentoxifylline and 52 of the 99 (53%) patients receiving placebo.

Conclusions

The difference in the healing rates between patients taking pentoxifylline and those taking placebo did not reach statistical significance.

Key messages

Leg ulcers cost the NHS around £400 million per annum

50%-75% of venous leg ulcers can be succesfully treated with dressings and compression bandages but take many months to heal

A drug that reduced the healing time of venous ulcers would be useful, although no agent has been proved to be effective to date

Trials with pentoxifylline, a vasoactive drug used in the treatment of peripheral vascular diseases, as an adjunct to the treatment of venous ulcers have been inconclusive

At the 5% level, pentoxifylline had a non-significant effect on healing rates of pure venous ulcers

Introduction

Leg ulcers have a prevalence of about 1% of the adult population in Great Britain.1,2 The most recent (1992) estimate of the cost of treatment to the NHS was around £400 million per annum.3 Several clinical trials have shown that treatment with carefully chosen and meticulously applied ambulatory compression bandages and dressings for several months resulted in failure in 30% to 60% of patients with ulcers.4–6 A drug that improved healing rates would be a useful adjunct to other treatment methods. Pentoxifylline, a vasoactive drug that reduces leucocyte adhesion and has mild fibrinolytic effects, is potentially such an agent, since it might interfere with two processes believed to occur in the pathogenesis of venous leg ulceration.7,8

Pentoxifylline is currently prescribed for the treatment of peripheral arterial disease and its complications. The normal dose is 400 mg two or three times daily at a cost of £24.93 for a pack of 90×400 mg tablets at September 1998 prices.9 If the drug is taken three times daily, as in our trial, the daily cost is 83p.

Previous clinical trials investigating the possible use of pentoxifylline in the treatment of leg ulcers have produced conflicting results.10–12 It is possible that the outcome of some of these studies was influenced by the inclusion of patients with conditions that might be affected differently by pentoxifylline, such as those with an element of arterial impairment. The Lothian and Forth Valley Leg Ulcer Study Group therefore decided to conduct a trial in patients with strictly defined venous ulcers, to determine whether pentoxifylline would be a useful adjunct to dressings and ambulatory compression therapy in this group.

Our primary aim was to determine whether pentoxifylline 400 mg (Trental 400; Hoechst Marion Roussel, Uxbridge) taken orally three times daily, in addition to ambulatory compression bandages and dressings, improves the healing rate of pure venous ulcers. Our secondary aim was to test the safety and tolerability of the drug when used for this purpose.

Participants and methods

Trial structure

Our trial formed the major component of a linked series of trials, with all patients with leg ulcers considered for entry into one of the trials depending on the cause of ulceration. This paper reports the trial on ulcers of proved venous disease, uncomplicated by diabetes, arterial impairment, or other systemic conditions. The trial used a two centre randomised, parallel group, factorial design. The treatments we evaluated were alternative pharmaceutical, bandaging, and dressings materials. The pharmaceutical treatment was investigated double blind, but this was not feasible for the other treatments. The statistical design of the whole trial has been described in detail elsewhere.13 Our paper concentrates solely on the pharmaceutical component of the study. The results of the dressings and bandages arms and the arterial stratum will be reported separately elsewhere.

Exclusion criteria

The study was approved by the ethical committee at each centre. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before entry to the trial. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or over, with pure venous ulcers present for at least 2 months. For the purposes of the trial “pure” venous ulcers were defined as those where there was established venous disease, confirmed by ultrasonography, and in which other major causal factors were excluded. Criteria for exclusion of potential participants were: (a) myocardial infarction in the past 3 months, major haemorrhage in the past 8 weeks, poor compliance with treatment, or hypersensitivity to methylxanthines, pentoxifylline, and drinks containing cola or caffeine; (b) systematic treatment with corticosteroids, cytotoxic agents, naftidrofuryl, pentoxifylline, oxerutin, anticoagulant or fibrinolytic agents, or an experimental drug that was currently being taken or taken within the past 3 months; (c) lumbar sympathectomy within the past 3 weeks; (d) the presence of right heart failure, a serum creatinine concentration greater than 180 μmol/l, hepatic insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, malignant disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or other severe connective disorder, limited physical capacity or total immobility, or an infected ulcer or gangrene at the ulcer site; (e) an ulcer size of less than 1 cm in one dimension; (f) the presence of ulcer for less than 2 months; (g) admission to hospital likely to be required for more than 10 days; (h) pregnancy, lactation, or women not using adequate contraception; and (i) a life expectancy of less than 6 months.

Reference ulcer

All patients presenting at the leg ulcer clinics of the Edinburgh and Falkirk royal infirmaries were considered. Each patient was included only once. Where the ulcers were bilateral, the leg with the largest ulcer was designated as the trial leg, and the largest ulcer on the trial leg was designated as the reference ulcer. All reference ulcers were at least 1 cm in the major diameter.

Patients were randomised in a 1:1 ratio, by centre, to receive pentoxifylline 400 mg three times daily or matching placebo, and they were also randomised to receive one of the two bandaging treatments and one of the two dressings (see website). The treatments were packaged, supplied, and labelled with consecutive patient numbers in each centre by the manufacturer. The pentoxifylline and placebo tablets looked identical to ensure that the study was double blind with respect to drug. On acceptance into the trial, participants were assigned the next available patient number. The dressings and bandages were allocated by opening the correspondingly numbered, sealed, opaque envelope.

Participants

We excluded 239 of 525 (45.5%) potential participants—76 for ulcer related reasons: ulcers too small (50 patients), diabetic patient needing compression therapy,11 healed ulcer or not an ulcer,6 short duration,4 and other5; 56 owing to the patient’s condition or diseases: immobile or frail,14 required hospital admission,11 raised serum creatinine concentration,8 mental illness,5 malignancy,4 communication difficulties,3 heart failure,2 hepatic insufficiency,2 death before randomisation,1 and other6; 49 who refused to participate; 25 for administrative reasons: geographical,12 non-compliance,10 and taking part in other trials3; 23 related to treatment: taking anticoagulants11 or taking corticosteroids12; and 10 related to drug sensitivities: granuflex,6 methylxanthines,2 and multiple drugs,2

The duration of treatment was either until all ulcers on the designated trial leg were healed—that is, fully epithelialised—or until 24 weeks of treatment had been completed. The randomised dressings were a knitted viscose dressing (NA; Johnson and Johnson, Ascot) or a hydrocolloid dressing (Improved Formulation Granuflex; ConvaTec, Uxbridge). The randomised compression treatments were an elastic single layer method (Granuflex Adhesive Compression Bandage; ConvaTec), or a four layer bandaging regimen (Velband; Johnson and Johnson), crêpe (Smith and Nephew, Hull), elset (Seton, Oldham), and coban (3M, Loughborough) applied by standardised bandaging techniques. Patients attended weekly for renewal of their dressings. Healing was monitored by tracing the ulcers on entry and at intervals of 4 weeks. The tracings were subsequently measured by planimetry (not reported here).

If the treatment was known to be interrupted for longer than 14 days for whatever reason during the course of the trial, the patient continued to be followed up but was withdrawn from the study and analysed as a failure of treatment. To monitor compliance all used and unused treatment containers were recovered at each monthly visit and when each patient completed the trial, and these were returned to the manufacturer for checking. Tablet counts were conducted at the end of the study.

Measurements of outcome

The principal efficacy variable was the complete healing of all ulcers on the reference leg by 24 weeks of treatment. A secondary efficacy variable was time to healing.

Results

Overall, 101 patients were randomised to receive pentoxifylline and 99 to receive placebo. The groups were comparable after randomisation (table). Twenty two patients were withdrawn from the trial, 11 from each group, but they were included in the analysis as failure to heal on treatment. Two patients in each group developed, or were found to have, exclusion criteria after randomisation. Three patients in the placebo group and one in the pentoxifylline group discontinued their drug when they were admitted to hospital with intercurrent illnesses. Two patients taking pentoxifylline but none taking placebo withdrew because of gastrointestinal symptoms (box). No significant differences were found between the groups. The drug seemed to be acceptable to most patients and safe, as adverse reactions that resulted in discontinuation of the drug were few.

Reasons for withdrawal from trial (pentoxifylline group, placebo group)

Side effectsGastrointestinal symptoms (2, 0)Headaches (0, 2)Sleep disturbance (1, 0)Hot flushes (1, 0)Unpleasant feelings (0, 1)

No reason given (0, 1)

Trial drug stopped when patient was admitted to hospital (1, 3)

Intercurrent illness (1, 0)

Exclusion criteria discovered or developed after entry to trial (2, 2)

Drug omitted (no specific reason given) for more than 14 days (1, 2)

Died (2, 0)

Number of ulcers healed

The ulcers of 65 (64%) patients given pentoxifylline and 52 (53%) given placebo were completely healed within 24 weeks. The absolute difference in healing rates was 11% (95% confidence interval 2% in favour of placebo to 25% in favour of pentoxifylline).

Time to healing

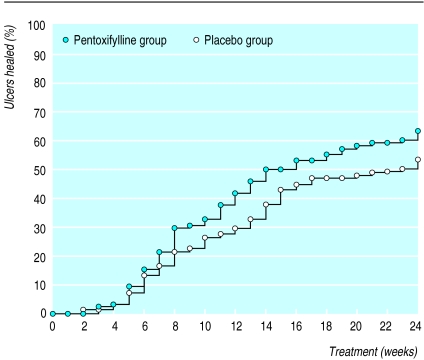

The figure shows that during the first 6 weeks 14% of the ulcers had healed and that there was little difference between the pentoxifylline and placebo groups. After a further week, a slight improvement in healing rates with pentoxifylline became apparent. This continued until the end point at 24 weeks when 64% of ulcers were healed in the pentoxifylline group compared with 53% in the placebo group.

Discussion

Previous studies have suggested that pentoxifylline might be a useful adjunct to ambulatory compression bandaging and dressings in the treatment of leg ulcers. Pemler et al claimed considerable improvements in a trial of 513 patients with chronic leg ulcers, which was uncontrolled, unrandomised, without a clear end point, and with undefined ulcer aetiology.11 One hundred and sixty of the patients had diabetes. Ramani et al have since shown that pentoxifylline was beneficial to healing and prognosis in a trial of 40 patients with diabetic ulcers.12

In a randomised, controlled trial of 80 patients with pure venous ulcers, Colgan et al achieved 64% healing rates with pentoxifylline and 34% with a placebo after 6 months of treatment.14 These results were significant at the conventional 5% level. The 64% healing rate for the pentoxifylline group was similar to ours, whereas that for the placebo was much lower.

We ensured that the ulcer disease was clearly defined by recruiting only patients with “pure” venous ulcers and by rigorously excluding those with serious diseases, such as diabetes, which might have been affected by giving pentoxifylline and consequently might have altered the healing rates. Two hundred patients, on the basis of 80% power to detect statistically significant differences if the true healing rates at a fixed time were 60% and 40%, was a sufficiently large number to show an effect of pentoxifylline on ulcer healing if such existed.

As there were no differences in healing rates between the groups during the first 6 weeks of treatment, a short treatment period would not have produced a clear result. The trial duration of 24 weeks allowed sufficient time to show whether there were differences in healing rates between the pentoxifylline and placebo groups. In our trial, slightly more ulcers were healed with pentoxifylline, and more quickly, than with the placebo. Within 24 weeks, we achieved 53% healing in the placebo group and 64% in the pentoxifylline group, but this difference was not significant at the 0.05 level.

Supplementary Material

Table.

Characteristics of pentoxifylline and placebo groups after randomisation. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Patients’ characteristics | Pentoxifylline (n=101) | Placebo (n=99) |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 30 | 38 |

| Female | 71 | 61 |

| Former smoker | 43 | 41 |

| Current smoker | 14 | 18 |

| Mean (SD) age (range) | 70.8 (11.3) (35-91) | 68.1 (8.9) (34-91) |

| Ulcer details (median, interquartile range) | ||

| Years since first ulcer | 3 (1-14) | 5 (1-20) |

| No of episodes of ulceration | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| Duration of reference ulcer (months) | 6 (3-12) | 4 (2-9) |

| Maximum diameter of reference ulcer (mm) | 27 (17-41) | 29 (18-40) |

Figure.

Life table analysis of time to complete healing of all ulcers on reference leg

Acknowledgments

We thank D Brown, E Hill, J Straub, C Kaufman, J Seaton, and G Young for treating the patients, collecting data, and maintaining the trial records. A Murray and J Howlett did the secretarial work.

Footnotes

Funding: The Lothian and Forth Valley Leg Ulcer Study Group was supported by a grant from the chief scientist of the Scottish Office Home and Health Department. This research was also supported financially by Hoechst Marion Roussel and ConvaTec.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV. Chronic ulcer of the leg: clinical history. BMJ. 1987;294:1389–1391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6584.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornwall JV, Dore CJ, Lewis JD. Leg ulcers: epidemiology and aetiology. Br J Surg. 1986;73:693–696. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosanquet N. Costs of venous ulcers: from maintenance therapy to investment programmes. Phlebology. 1992;(7 suppl)1:44–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Brown D, Gibson B, Prescott RJ, et al. Lothian and Forth Valley leg ulcer healing trial. Part 1: elastic versus non-elastic bandaging in the treatment of chronic leg ulceration. Phlebology. 1992;7:136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JM, Dore CJ, Charlett A, Lewis JD. A randomised trial of biofilm dressing for venous leg ulcers. Phlebology. 1992;7:108–113. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnand KG, Lea Thomas M, O’Donnell T, Browse NL. The relationship between post-phlebitic changes in the deep veins and the results of surgical treatment of deep venous ulcers. Lancet. 1976;2:936–938. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnand KG, Whimster I, Naidoo A, Browse NL. Pericapillary fibrin in the ulcer-bearing skin of the leg: the cause of lipodermatosclerosis and venous ulceration. BMJ. 1982;285:1071–1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6348.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleridge-Smith PD, Thomas P, Scurr JH, Dormandy AD. Causes of venous ulceration: a new hypothesis. BMJ. 1988;296:1920–1922. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6638.1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Medical Association and Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. British national formulary. London: BMA and PSGB; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitgasser H. The use of pentoxifylline (Trental) in the treatment of leg ulcers: results of a double-blind trial. Pharmtherapeutica. 1983;3(suppl):1. :143-51. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pemler K, Penth B, Adams H-J. Pentoxfyllin Medikation im Rahmen der Ulcus cruris Behandlung. Fortschr Med. 1979;21:1019–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramani A, Kundaje GN, Nayak MN. Hemorheologic approach in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Angiology. 1996;44:623–626. doi: 10.1177/000331979304400805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescott RJ, Nelson EA, Dale JJ, Harper DR, Ruckley CV. Design of randomised controlled trials in the treatment of leg ulcers: more answers with fewer patients. Phlebology. 1998;13:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colgan M-P, Dormandy JA, Jones PW, Schraibman IG, Shanik DG, Young RAL. Oxpentifylline treatment of venous ulcers of the leg. BMJ. 1990;300:972–975. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6730.972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.