Abstract

Objective

To describe the declining trend in maternal mortality observed in Mongolia from 1992 to 2007 and its acceleration after 2001 following implementation of the Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy by the Ministry of Health and other partners.

Methods

We performed a descriptive analysis of maternal mortality data collected through Mongolia’s vital registration system and provided by the Mongolian Ministry of Health. The observed declining mortality trend was analysed for statistical significance using simple linear regression. We present the maternal mortality ratios from 1992 to 2007 by year and review the basic components of Mongolia’s Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy for 2001–2004 and 2005–2010.

Findings

Mongolia achieved a statistically significant annual decrease in its maternal mortality ratio of almost 10 deaths per 100 000 live births over the period 1992–2007. From 2001 to 2007, the maternal mortality ratio in Mongolia decreased approximately 47%, from 169 to 89.6 deaths per 100 000 live births.

Conclusion

Disparities in maternal mortality represent one of the major persisting health inequities between low- and high-resource countries. Nonetheless, important reductions in low-resource settings are possible through collaborative strategies based on a horizontal approach and the coordinated involvement of key partners, including health ministries, national and international agencies and donors, health-care professionals, the media, nongovernmental organizations and the general public.

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire la tendance à la baisse de la mortalité maternelle observée en Mongolie entre 1992 et 2007 et son accélération après 2001, suite à la mise en œuvre de la Stratégie de réduction de la mortalité maternelle par le Ministère de la santé et d’autres partenaires.

Méthodes

Nous avons réalisé une analyse descriptive des données de mortalité maternelle collectées par l’intermédiaire du système mongol d’enregistrement de l’état-civil et fournis par le Ministère de la santé mongol. Nous avons analysé la tendance à la baisse de la mortalité pour évaluer sa significativité statistique par régression linéaire simple. Nous présentons les ratio de mortalité maternelle annuels de 1992 à 2007 et passons en revue les composantes de base de la Stratégie de réduction de la mortalité maternelle mongole pour les périodes 2001-2004 et 2005-2010.

Résultats

La Mongolie a obtenu une baisse annuelle statistiquement significative de son ratio de mortalité maternelle de près de 10 décès pour 100 000 naissances vivantes sur la période 1992-2007. De 2001 à 2007, le ratio de mortalité maternelle mongol a diminué d’environ 47 %, passant de 169 à 89,6 décès pour 100 000 naissances vivantes.

Conclusion

Les disparités en termes de mortalité maternelle représentent l’une des principales sources d’inégalités persistantes entre les pays à faible revenu et les pays riches. Néanmoins, des diminutions importantes de cette mortalité sont possibles dans les régions démunies si l’on fait appel à des stratégies collaboratives reposant sur une approche horizontale et sur la participation coordonnée de partenaires clés, dont les ministères de la santé, les agences et les donateurs nationaux et internationaux, les professionnels de santé, les médias, les organisations non gouvernementales et la population générale.

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir la tendencia decreciente de la mortalidad materna observada en Mongolia entre 1992 y 2007 y su aceleración a partir de 2001, después de que el Ministerio de Salud y otros asociados aplicaran la estrategia de reducción de la mortalidad materna.

Métodos

Realizamos un análisis descriptivo de los datos de mortalidad materna reunidos a través del sistema de registro civil de Mongolia y proporcionados por el Ministerio de Salud. La tendencia observada de reducción de la mortalidad fue analizada mediante regresión lineal simple para determinar la significación estadística. Presentamos las razones de mortalidad materna entre 1992 y 2007 para cada año y examinamos los componentes básicos de la estrategia de reducción de la mortalidad materna de Mongolia en 2001–2004 y 2005–2010.

Resultados

Mongolia logró una disminución anual estadísticamente significativa de su razón de mortalidad materna de casi 10 muertes por 100 000 nacidos vivos durante el periodo 1992–2007. Entre 2001 y 2007, la razón de mortalidad materna disminuyó aproximadamente un 47%, de 169 a 89,6 defunciones por 100 000 nacidos vivos.

Conclusión

Las disparidades de la mortalidad materna son una de las principales inequidades en salud que aún persisten si se comparan los países de bajos recursos y los que cuentan con altos recursos. Sin embargo, es posible lograr reducciones importantes en los entornos con recursos escasos aplicando estrategias de colaboración basadas en un enfoque horizontal y coordinando la participación de asociados clave, como los ministerios de salud, los organismos y donantes nacionales e internacionales, los profesionales de la salud, los medios de comunicación, las organizaciones no gubernamentales y el público en general.

ملخص

الغرض

وصف الاتجاه المنحسر لوفيات الأمهات الملاحظ في منغوليا من عام 1992 إلى 2007، ثم زيادته المتسارعة بعد عام 2001 عقب تطبيق استراتيجية خفض معدلات وفيات الأمومة من قبل وزارة الصحة وسائر الشركاء.

الطريقة

قام الباحثون بتحليل وصفي لمعطيات وفيات الأمومة التي جُمِعَت من خلال نظام السجل المدني وقدمتها وزارة الصحة المنغولية. وتم تحليل الاتجاه المنحسر والملاحظ لوفيات الأمومة بغرض الوصول إلى إحصاءات يعتد بها، وذلك باستخدام التحوّف الخطي البسيط. وصنّف الباحثون نسب وفيات الأمهات للأعوام من 1992 إلى 2007 بحسب السنة، مع مراجعة المكونات الأساسية لاستراتيجية منغوليا لخفض معدلات وفيات الأمومة للأعوام 2001-2004 و 2005-2010.

الموجودات

حققت منغوليا انخفاضاً سنوياً يعتد به إحصائياً في خفض معدل وفيات الأمومة بحوالي عشر وفيات لكل مئة ألف مولود حي، وذلك على مدى الفترة من 1992 إلى 2007. وانخفضت من عام 2001 حتى 2007 معدلات وفيات الأمومة في منغوليا بحوالي 47%، أي من 169 وفاة إلى 89.6 وفاة لكل مئة ألف مولود حي.

الاستنتاج

تمثل الاختلافات في وفيات الأمومة واحداً من أوجه الإجحاف الصحي الجوهري المستمر بين البلدان المنخفضة الموارد والبلدان المرتفعة الموارد. إلا أنه يمكن إحراز انخفاض هام في وفيات الأمهات في الأماكن المنخفضة الموارد من خلال استراتيجيات تعاونية ترتكز على أسلوب أفقي يحقق المشاركة المنسقة للشركاء الرئيسيين، ومنهم وزارات الصحة، والوكالات الوطنية والدولية والمانحين، والعاملين في الرعاية الصحية، والإعلام، والمنظمات غير الحكومية، والجماهير العامة.

Introduction

Global disparities in women’s reproductive health represent one of the starkest health inequities of our times and a major social injustice. Each year approximately 530 000 women die from the complications of pregnancy and childbirth; 99% of these deaths occur within the most disadvantaged population groups in the poorest countries of the world.1 Recent analyses show that these deaths are increasingly concentrated in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where 45% and 50% of all maternal deaths occur, respectively.1,2 While women in developed countries can generally expect to experience safe pregnancies and positive birth outcomes, these figures indicate that women in low-resource nations still face a high risk of dying during pregnancy, delivery and the postpartum period. This unacceptable discrepancy must be addressed if the world is to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5, which calls for a three-quarters reduction in 1990 maternal mortality levels worldwide and for universal access to reproductive health services by 2015.3

Despite the disappointing lack of progress in reducing global maternal mortality since the launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative over 20 years ago, strides in the reduction of maternal deaths have been achieved in Latin America, south-eastern and eastern Asia and northern Africa, with notable declines occurring in several developing countries (including Bangladesh, China, Egypt, Honduras, Malaysia and Sri Lanka).4–7 The Countdown to 2015 report for 2008 also shows that 12 of the 68 countries in the world with the highest burdens of maternal and child mortality (Azerbaijan, Brazil, China, Egypt, Guatemala, Mexico, Morocco, Peru, the Philippines, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan) are now categorized as making good progress towards MDG 5.2,8 These findings indicate that attainment of MDG 5 is possible.

Mongolia, with a population of about 2.6 million and approximately 50 000 births per year,9 is a lower-middle-income Asian country where maternal mortality has decreased over the past two decades. In this article we present Mongolia’s declining maternal mortality ratios from 1992 to 2007 and highlight the acceleration of this decline between 2001 and 2007 following the implementation of the Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy (MMRS) 2001–2004 and 2005–2010. We discuss the features of the MMRS that probably contributed to Mongolia’s maternal mortality declines in the past 10 years, with emphasis on specific interventions and the collaborative strategy adopted for the implementation process. It is important to note that the interventions introduced through the MMRS comply with current recommendations for addressing maternal mortality through prioritization of intrapartum care and the introduction of a comprehensive horizontal strategy.10,11 These interventions were implemented through productive partnerships between the Ministry of Health and other reproductive health stakeholders, including local governments, health-care professionals, national and international agencies and donors, nongovernmental organizations, the media and the general public.

Given that we are already past the mid-point between 2000 – when the MDGs were ratified by 189 countries – and 2015, it is urgent that country success stories be analysed and widely disseminated so they can be replicated elsewhere. Documentation of the success of Mongolia’s collaborative and comprehensive approach is highly relevant given the growing concentration of maternal deaths in the Asian region. This approach may prove useful for other countries as they work towards achieving MDG 5.

Methods

Maternal mortality ratios for the years 1992–2007 and a description of the components of the 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 MMRS were provided by the Mongolian Ministry of Health.12,13 The observed declining mortality trend was analysed for statistical significance using simple linear regression with SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States of America).

Data on maternal deaths and births were collected through a vital registration system that is characterized as “good” by the United Nations (i.e. at least 90% coverage of births and deaths) and that has an adequate attribution of cause of death.1 Since 1992, Mongolia has applied the standard definition for maternal deaths included in guidelines proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO).14,15

Descriptive statistics

Estimates indicate that the percentage of women receiving skilled delivery care remained stable over the study period at approximately 99%, and that the percentage of women receiving at least one antenatal care visit increased slightly, from 97% to 99% between the late 1990s and 2006.16,17 Mongolia’s crude birth rate declined steadily from 33 to 19 per 1000 people between 1990 and 2006. Likewise, the total fertility rate dropped from 4.3 children per woman in 1990 to 1.9 in 2006.

Strategy 2001–2004

Table 1 presents the eight objectives outlined in the MMRS 2001–2004, examples of activities performed to accomplish each objective, a list of the parties responsible for the implementation of each objective and sources of financial support.12 The complete text of the MMRS is available upon request.

Table 1. Main characteristics of the Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy 2001–2004 in Mongolia.

| Objective | Examples of activities implemented | Responsible parties | Financial resources | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. To create a favourable environment for community mobilization and participation to reduce maternal mortality (involvement of district and provincial governors, decision-makers, policy-makers, general public) | Mobilize community involvement from the level of district governors to the general public into reproductive health advocacy training, changing attitudes and gaining support. | MoH, MCHRC | UNICEF, UNFPA, local governments | |||

| Organize annual governors’ conferences on the situation of maternal and child mortality and morbidity. | ||||||

| Re-establish maternal waiting homes. | ||||||

| Provide transportation costs for pregnant women between their homes and the maternal waiting homes. | ||||||

| 2. To introduce and monitor client-centred services at all levels of the health-care system in order to improve the quality of a comprehensive obstetric care package (involving health-care units at all levels) | Establish a clear obstetric and newborn care ackage including antenatal care, and care during delivery and postpartum period. | MoH, MCHRC, NUM, HIV/AIDS Centre, WHO, City Health Department, UNFPA, NHDC, PHI, GTZ | UNFPA, WHO, GTZ, UNICEF, PHI, MoH, NHDC | |||

| Establish clear competencies for health-care units at all levels of the system. | ||||||

| 3. To develop standards for a mother and child comprehensive care package and introduce it at all levels of obstetric care | Review and revise job descriptions for community health workers, midwives, general practitioners and obstetrician-gynaecologists. | MoH, Mongolian Association of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, MCHRC | MoH, WHO | |||

| Translate, adapt, distribute and implement at all levels the WHO “Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth” guidelines. | ||||||

| Train at least two trainers in each province on the WHO guidelines and on how to organize training for doctors in districts and villages. | ||||||

| Provide essential drugs to all maternal-neonatal service providers. | ||||||

| 4. To organize, in association with the mass media, education activities for families and the public on safe motherhood issues and pay more attention to vulnerable groups in the population who lack access to health services (involving central and local governmental organizations, nongovernmental organizations, donor countries and international organizations, health institutions, press agencies) | Develop and implement an information, education and communication (IEC) strategy on safe motherhood. | MoH, PHI, NHDC | UNFPA, UNICEF, GTZ | |||

| Develop high-quality IEC material on safe motherhood and distribute. | ||||||

| Train and improve health workers “safe motherhood” knowledge and skills working in IEC. | ||||||

| 5. To encourage and expand participation by nongovernmental organizations and the public in safe motherhood activities (involving central and local governmental organizations and nongovernmental organizations) | Educate pregnant women, their families and communities on the signs of pregnancy complications. | MoH, MCHRC, Health Department, NGOs | UNFPA, UNICEF | |||

| Promote maternal waiting homes. | ||||||

| Encourage training for volunteers and their involvement in safe motherhood initiatives. | ||||||

| 6. To improve management of safe motherhood services and counselling at all levels | Develop and implement a regulation on medical assistance for women with normal high-risk pregnancies. | MoH | MoH | |||

| Develop and implement a regulation on referral and treatment of high-risk pregnancies and women with pregnancy complications. | ||||||

| Improve maternal mortality information/registration card. | ||||||

| 7. To improve the professional ability and skills of medical personnel and to develop a salary and remuneration scheme based on work performance | Improve the coverage of professional degree exams by allowing doctors to take such exams at the work place. | MoH, NUM, Medical College | UNFPA, WHO, UNICEF, ADB, GTZ | |||

| Investigate the possibility for post-graduate training for service providers at the work place. | ||||||

| Examine how salary increases can be made for doctors and health providers in rural areas. | ||||||

| Revise the under- and post-graduate training curriculum for medical students on prevention and management of obstetric complications. | ||||||

| 8. To develop and implement guidelines on early detection of pregnancy complications at all levels of the health-care delivery system and timely referral to the next level | Develop the guidelines “Early diagnosis of pregnancy complications, referral and treatment without delay at the next level of care.” | MoH, MCHRC, City and provincial health departments and hospitals | MoH, City and provincial governors, Health Department, Provincial general hospitals | |||

ADB, Asian Development Bank; GTZ, German Technical Assistance Organization; MCHRC, Maternal and Child Health Research Centre; MoH, Ministry of Health; NGO, nongovernmental organization; NHDC, National Health Development Centre; NUM, National University of Mongolia; PHI, Public Health Institute; UNFPA, United Nations Population Fund; UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund.

The MMRS 2001–2004 introduced several procedures enacted at the facility, provincial and ministerial levels to ensure accurate registration of maternal deaths (not shown in Table 1). These procedures included reporting of deaths within a 24-hour period to the appropriate health department, forensic examination performed by a pathologist and clinical pathology conferences and training opportunities on how to calculate the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) and categorize maternal deaths by major causes.12 Medical records were transmitted to responsible officers at the Ministry of Health, where cases were reviewed by a Health Minister Committee every three months and, when necessary, were re-analysed by an ad hoc committee. In 2001, “maternal death review committees” responsible for reviewing and confirming each maternal death and for submitting final reports to the Ministry of Health were established at the provincial level. A committee at the Ministry of Health was convened periodically to review these reports and to develop recommendations and the next plan of action to further reduce maternal mortality. The maternal death reporting form was also revised in 2001 to require the collection of additional information in order to reduce misclassification. As these changes should have resulted in increased capture of maternal deaths, the decline in maternal mortality achieved following the implementation of the MMRS 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 can be considered even more remarkable.

Results

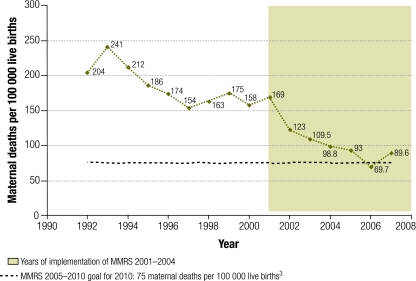

During the 1992–2007 period, the MMR peaked in 1993 at 241 per 100 000 live births and then fell approximately 62.8%, to 89.6 per 100 000 live births in 2007 (Fig. 1). More specifically, substantial declines occurred between 1993 and 1996, followed by minor fluctuations between 1997 and 2000, an accelerated decline from 2001 to 2004, and minor fluctuation but still a slight decrease from 2005 to 2007. Between 2001 and 2007, when the MMRS 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 were implemented, the MMR showed an overall decrease of 47%, falling from 169 to 89.6 deaths per 100 000 live births.

Fig. 1.

Maternal mortality ratio by year, Mongolia, 1992–2007

MMRS, Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy.

Although random fluctuations may be responsible for some of the observed declines in Mongolia’s MMR from 1992 to 2007, application of a linear regression model shows a significant decrease in the MMR of almost 10 deaths per year (9.8; 95% confidence interval, CI: 7.8 to 11.7; P < 0.0001). The linear trend explains 89% of the variation in the MMR data points. It is also noteworthy that Mongolia’s MMR dropped below 100 (the upper threshold for categorization as “low maternal mortality”)2 in 2004, which may explain why progress was slower from that date forward.

Discussion

Implementation of the MMRS 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 by the Mongolian Ministry of Health and collaborating organizations resulted in a marked reduction in maternal deaths. Mongolia’s unique sociopolitical history enabled it to implement a strategy involving the delivery of high-quality sexual and reproductive health-care services starting in 2001. That history is summarized below, along with the key elements of Mongolia’s MMRS that probably contributed to the dramatic reduction of maternal mortality observed between 2001 and 2007.

Decline from 1993 to 2001

Mongolia is a vast country with one of the world’s lowest population densities. Under the sphere of influence of the former Soviet Union, the country entered into a democratic phase in 1990 after the Soviet Union’s collapse. The implications of this transition on Mongolia’s health-care system and on sexual and reproductive health outcomes are extensively reviewed in two recent publications.15,18 Briefly, the years immediately following the political transition witnessed a deterioration of the health-care system and a resultant rise in maternal mortality. After 1993, maternal mortality decreased due to the reintroduction of “maternal waiting homes” (also known as maternity rest homes), improvements in the supply of emergency drugs and increased training of health-care workers in sexual and reproductive health (including obstetrics) through assistance from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Maternal waiting homes are a particularly important component of the health-care referral system because women from rural areas must travel large distances to reach provincial health centres, which can keep them from receiving timely care.18 Support from UNFPA also increased; it ensured the availability of contraceptives and strengthened the logistic management system of the National Reproductive Health Programme.15 In addition, the liberalization of abortion legislation in 1989 led to reductions in poor outcomes from unsafe abortions.

The combination of these health system reform and policy measures culminated in the stabilization of the MMR at around 165 deaths per 100 000 live births by the second half of the 1990s, a reduction from over 200 deaths per 100 000 live births in the early 1990s (Fig. 1).12 In addition, greater support for education and communication campaigns about family planning led to a wide acceptance of, and greater demand for, sexual and reproductive health services among the population. In summary, the 1990s witnessed important improvements in both supply and demand factors related to women’s sexual and reproductive health, thus creating a favourable environment for the implementation of the MMRS 2001–2004.

Highlights of MMRS 2001–2004

The MMRS 2001–2004 in Mongolia incorporated many of the core health sector strategies and other elements promoted internationally and associated with successful programmes aimed at reducing maternal mortality.11,12 A critical factor in the success of Mongolia’s MMRS was its participatory framework. The Ministry of Health collaborated closely with local governors, city hospitals and provincial, district and rural health facilities. It also received active and coordinated support from international donors, governmental and nongovernmental organizations, United Nations agencies, the media and the general public. A tight networking system was fostered among nongovernmental organizations, resulting in more effective and integrated training of care providers and greater efficiency in the auditing and implementation of specific sexual and reproductive health projects in local areas. Television and radio programmes endorsed by the Ministry of Health that provided information about safe motherhood were aired on Tuesdays and Saturdays. It is important to note that these media-based programmes raised awareness about sexual and reproductive health issues among the male population, encouraging men and prospective fathers to become more supportive of, and concerned about, the health of their wives and newborns.

Following the introduction of the MMRS, reduction of maternal mortality was adopted as a national priority and a basis for evaluating the performance of governors and civil servants, thus generating greater political commitment to the advancement of women’s reproductive health at local and national levels.15 For example, a “mother-friendly governor” initiative was implemented to encourage governors to take more responsibility for the maternal and neonatal health conditions in their jurisdictions and to award those who made strides in improving those conditions.

Another factor that ensured the successful implementation of the MMRS was the adoption of “substrategies” by provinces, districts and, in some cases, communities. The substrategies were designed to utilize available resources, sometimes in combination with existing local programmes, to target specific sexual and reproductive health issues prevalent in a given area. This practical approach enabled the implementation of effective programmes tailored to local conditions.

Strong emphasis was also given to capacity building, professionalization of the health workforce and intersectoral collaboration, reflecting the approach adopted in western Europe and the United States of America that achieved dramatic reductions in maternal mortality in the first half of the 20th century.18 Specific efforts included increasing the availability of free or reduced-cost services and transportation, strengthening formalized referral systems by opening up more maternal waiting homes, implementing the mother-friendly hospital initiative and making health-care providers accountable to health authorities.10 Special contracts gave incentives to experienced doctors to accept work in remote rural hospitals. In addition, competencies for health-care units at all levels of the system were clearly established, and supplemental training was provided to health-care practitioners.19 This training was based on WHO guidelines for managing complications during pregnancy and childbirth adapted to suit Mongolia’s circumstances.20 In total, 90% of obstetrician-gynaecologists received training on these guidelines, and 80% of doctors based in district hospitals and general practitioners received training on the delivery of sexual and reproductive health services. Finally, a standard curriculum was developed to inform local decision-makers about sexual and reproductive health issues, and a midwifery course was re-opened at the Medical College in 2002.

Although substantial progress in reducing maternal mortality was achieved by the MMRS 2001–2004, key challenges persisted, such as making health-care providers more accountable to the public and reducing regional and socioeconomic disparities in maternal mortality. For example, maternal mortality remained higher in the less-developed western region and among unemployed women and women from semi-nomadic, pastoral households or those who lacked civil registration because of recent migration.12 Adolescents (under 20 years) constituted 5.5% of all women giving birth, the prevalence of sexually transmitted infections was increasing and complications from abortions still represented an important cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 7.1% of maternal deaths.18 Furthermore, the government needed to determine how to balance its pro-natalist stance – a position stemming from Mongolia’s low population density – with a strong commitment to provide comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services to offset potential increases in adverse maternal health outcomes due to higher fertility rates.

To address these issues, the MMRS was re-evaluated in 2005. Box 1 presents the main features of the MMRS 2005–2010, along with those of the MMRS 2001–2004 for comparison. The updated MMRS aimed at reducing the above-noted inequities and keeping Mongolia on track for attainment of MGD 5. As part of this new strategy, the Ministry of Health collaborated with WHO to improve the capacity of health-care facilities to provide safer abortion services, including treatment of abortion complications.

Box 1. Comparison of the main objectives of the Maternal Mortality Reduction Strategy for 2001–2004 and 2005–2010.

2001–2004

1. To improve social mobilization to reduce maternal deaths.

2. To develop guidelines and standards on comprehensive reproductive health services, especially the referral system for each level of the health-care system.

3. To improve involvement of nongovernmental organizations and the community in safe motherhood.

4. To improve information and education campaign activities on reproductive health/safe motherhood.

2005–2010

1. To enhance participation of governmental, nongovernmental and donor organizations in implementation efforts, and to improve intersectoral collaboration and coordination of reproductive health and safe motherhood activities.

2. To upgrade management, organization, logistics and human resource capacity in the provision and supervision of maternal and neonatal care.

3. To improve quality of and access to reproductive health care, especially maternal and neonatal services, by rapid introduction of international standards and evidence-based practices.

4. To increase accessibility and availability of reproductive health and safe motherhood services for remote, migrant and other disadvantaged population groups.

5. To enhance participation of women, husbands, other family and community members in preventing pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum complications and ensuring prompt access to safe motherhood services.

The main limitations of this study are that we cannot demonstrate a clear causal association between the health and policy reform measures included in the MMRS 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 and Mongolia’s declining maternal mortality trend up until 2007, nor can we determine the portion of the trend attributable to the MMRS. Nevertheless, the large team of partners that worked to implement the MMRS have not been able to find or document other major health system or contextual changes that would account for the decline.

Future studies should examine these possible associations in more detail, including the role of economic growth and changes in women’s education and income earning opportunities in maternal mortality decreases. Given that the coverage rates of one antenatal visit and skilled delivery care were high throughout the 1992–2007 period, future research should pay particular attention to measuring the impact on maternal survival of improvements in the quality of care, including strengthened referral mechanisms, following the introduction of the MMRS. Research on changes in the cause distribution of maternal mortality between 2001 and 2007 would also shed light on the role of health sector reforms implemented as part of the MMRS.

Conclusion

Mongolia was able to achieve a 47% reduction in maternal mortality in only seven years (from 169 to 89.6 deaths per 100 000 live births between 2001 and 2007). This accomplishment is comparable to declines in MMR of 30–50% over 7–10 years in Egypt, Honduras, Malaysia and Sri Lanka – countries also viewed as successful case studies.10 Implementation of the comprehensive MMRS 2001–2004 and 2005–2010 probably contributed to this decline. Mongolia’s achievement thus far suggests that the stated aim of the MMRS 2005–2010 of reducing the maternal mortality ratio to 75 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births by 2010 is well within reach. ■

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill K, Thomas K, AbouZahr C, Walker N, Say L, Inoue M, et al. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 2007;370:1311–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Road map towards the implementation of the United Nations Millennium Declaration: report of the Secretary General. In: United Nations General Assembly, Fifty-sixth Session, New York, 16November2001 (Document A/56/326).

- 4.Koblinsky MA, editor. Reducing maternal mortality: learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Zimbabwe Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padmanathan I, Lilijestrand J, Martins J, Rajapaksa L. Lissner, de Silva A et al. Investing in maternal health in Malaysia and Sri Lanka Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawn JE, Tinker A, Munjanja SP, Cousens S. Where is maternal and child health now? Lancet. 2006;368:1474–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury ME, Botlero R, Koblinsky M, Saha SK, Dieltiens G, Ronsmans C. Determinants of reduction in maternal mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh: a 30-year cohort study. Lancet. 2007;370:1320–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61573-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryce J, Requejo JH. Tracking progress in maternal, newborn and child survival: the 2008 report (Countdown to 2015 report). New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations. World population prospects: the 2004 revision New York, NY: United Nations; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koblinsky M, Campbell OM. Factors affecting the reduction of maternal mortality. In: Koblinsky MA, ed. Reducing maternal mortality: learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Zimbabwe Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2003. pp. 5-37. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell OM, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368:1284–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maternal mortality reduction strategy 2001-2004 Ulaanbaatar: Ministry of Health; 2002.

- 13.Maternal mortality reduction strategy 2005-2010 Ulaanbaatar: Ministry of Health; 2005.

- 14.International classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janes CR, Chuluundorj O. Free markets and dead mothers: the social ecology of maternal mortality in post-socialist Mongolia. Med Anthropol Q. 2004;18:230–57. doi: 10.1525/maq.2004.18.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.United Nations Children’s Fund. Situation analysis of children and women in Mongolia Ulaanbaatar: UNICEF-Mongolia; 2007. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/Mongolia_SitAn_2007.pdf [accessed 21 September 2009].

- 17.Abou-Zahr CL, Wardlaw TM. Antenatal care in developing countries: promises, achievements and missed opportunities. An analysis of trends, levels and differentials, 1990-2001 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill PS, Dodd R, Dashdorj K. Health sector reform and sexual and reproductive health services in Mongolia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14:91–100. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Brouwere V, Tonglet R, Van Lerberghe W. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality in developing countries: what can we learn from the history of the industrialized West? Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:771–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]