Abstract

Altered phosphatidylcholine (PC) metabolism in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) can provide choline-based imaging approaches as powerful tools to improve diagnosis and identify new therapeutic targets. The increase in the major choline-containing metabolite phosphocholine (PCho) in EOC compared with normal and non-tumoral immortalized counterparts (EONT), may derive from a) enhanced choline transport and choline kinase (ChoK)-mediated phosphorylation; b) increased PC-specific phospholipase C (PC-plc) activity; c) increased intracellular choline production by PC deacylation plus glycerophosphocholine-phosphodiesterase (GPC-pd) or by phospholipase D (pld)-mediated PC catabolism, followed by choline phosphorylation. Biochemical, protein and mRNA expression analyses demonstrated that the most relevant changes in EOC cells were: 1) 12- to 25-fold ChoK activation, consistent with higher protein content and increased ChoKα (but not ChoKβ) mRNA expression levels; 2) 5- to 17-fold PC-plc activation, consistent with higher, previously reported, protein expression. PC-plc inhibition by tricyclodecan-9-yl-potassium xanthate (D609) induced in OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cancer cells a 30-to-40% reduction of PCho content and blocked cell proliferation. More limited and variable sources of PCho could derive, in some EOC cells, from 2- to 4-fold activation of pld or GPC-pd. Phospholipase A2 activity and isoforms’ expression levels were lower or unchanged in EOC compared with EONT cells. Increased ChoKα mRNA, as well as ChoK and PC-plc protein expression, were also detected in surgical specimens isolated from EOC patients. Overall, we demonstrated that the elevated PCho pool detected in EOC cells primarily resulted from upregulation/activation of ChoK and PC-plc involved in the biosynthetic and in a degradative pathway of the PC-cycle, respectively.

Keywords: ovarian cancer, phosphatidylcholine metabolism, NMR, choline kinase, phospholipase D, phospholipase C, glycerophosphocholine-phosphodiesterase

Introduction

Despite progress in clinical oncology, epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) continues to be the gynecological malignancy with the highest death rate in industrialized countries and a 5-year survival as low as 44% [1]. Suitable molecular imaging approaches could facilitate elucidation of mechanisms of EOC progression, improve clinical diagnosis and follow-up, and identify new therapeutic targets.

Detection of an aberrant phosphatidylcholine (PC) metabolism in tumors by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) [2,3] allowed for the identification of novel indicators of in vivo tumor progression by using choline-based MRS and positron emission tomography (PET) [4–8]. An elevation of the 1H MRS resonance at 3.2 ppm, mainly due to headgroups of choline-containing metabolites (tCho), is a common feature in several cancers including EOC [9–17]. Changes of the tCho spectral profile reflect altered contents and fluxes of phosphocholine (PCho), glycerophosphocholine (GPC) and free choline (Cho) in the PC-cycle (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Phosphatidylcholine metabolites.

A, The phosphatidylcholine (PC) cycle. Metabolites: CDP-Cho, cytidine diphosphate choline; Cho, choline; DAG, diacylglycerol; FFA, free fatty acid; G3P, sn-glycerol-3-phosphate; GPC, glycerophosphocholine; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; PA, phosphatidate; PCho, phosphocholine. Enzymes: Kennedy pathway: Chok, choline kinase (EC 2.7.1.32); ct, cytidylyltransferase (EC 2.7.7.15); pct, phosphocholine transferase (EC 2.7.8.2). Headgroup hydrolysis pathways: plc, phospholipase C (EC 3.1.4.3); pld, phospholipase D (EC 3.1.4.4). Deacylation pathway: plA1, phospholipase A1 (EC 3.1.1.32); plA2, phospholipase A2 (EC 3.1.1.4); lpl, lysophospholipase (EC 3.1.1.5); pd, glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.2). B, Quantification of aqueous metabolites (mean values ± SEM) in EOC and EONT cells [OSE (n=2); IOSE (n=4); hTERT (n=15)]). C, Relative PC contents (± maximum deviation for n=2; ± SD for n≥3) in EOC normalized to hTERT cells. In parenthesis, number of independent experiments.

Major mechanisms of PCho accumulation in tumor cells include enhanced choline transport and choline kinase (ChoK)-mediated phosphorylation and activation of PC-specific phospholipases [13,15,17–19]. These biochemical features can represent fingerprints of tumour progression and potential therapeutic targets [6,20–22].

Previous studies demonstrated that ChoK is upregulated by oncogenes, growth factors and carcinogens [22,23] and its ChoKα isoform can be constitutively activated in human tumor cells [24], in which it may act as prognostic factor [25,26]. Furthermore, specific pharmacologic or si-RNA ChoK inhibition have antiproliferative effects on cancer cells [18,27].

A neutral-active PC-specific phospholipase C (PC-plc) is also activated in EOC compared with non-tumoral EONT cells [15,28], inhibition of this enzyme being associated with reduced response of EOC cells to mitogens [28].

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the altered tCho profile in EOC cells, we here report on measurements of absolute activity rates of ChoK, PC-plc, phospholipase D (pld), and glycerophosphocholine-phosphodiesterase (GPC-pd), as well as on differential metabolic fluxes through the PC deacylation pathway in EOC and EONT cells. Comparative analyses of mRNA expression levels were also performed for: ChoKα and ChoKβ isoforms, citydylyltransferase (ct) and phosphocholine transferase (pct), pld1, pld2 and nineteen phospholipase A2 isoforms. The role of PC-plc in the intracellular accumulation of PCho in EOC cells and the effect of its inhibition on cell growth have been investigated. Analyses are also reported on ChoKα mRNA expression and on ChoK and PC-plc protein expression in a set of surgical specimens from EOC patients.

Materials and Methods

Epithelial ovarian non-tumoral and EOC cells

Ovary surface epithelial (OSE) cells, their stably immortalized non-tumoral variants (IOSE and hTERT) and the serous EOC cell lines OVCA3, SKOV3, CABAI and IGROV1 were prepared and cultured as described [15]. Four additional cell lines were used for microarray analysis: OVCA432 [15], INT-Ov1 and INT-Ov2 [29] and OAW42 (kindly provided by Dr. A. Ullrich, Max-Planck Institute, Germany). Tumor lines, but OAW42 maintained in MEM, were maintained as described [15].

Chemicals

1,2dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (C6PC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabarter, Alabama, US); trimethylsilyl-propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid sodium salt (TSP) from Merck & Co, Montreal, Canada; tetramethylsilane, CDCl3 and CD3OD from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA, US); tricyclodecan-9-yl-potassium xanthate (D609), sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, alkaline phosphatase (AP), glyceraldehydes 3-phospate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and the other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, US).

Clinical specimens

Clinical specimens, including OSE cells, were obtained with INT-Milan Review Board approval. And informed consent to use leftover biological material for investigation purposes was obtained from all patients. EOC samples were taken at the time of initial surgery from 21 patients with histologically confirmed EOC (stages III–IV according to International Federation Gynecologic Oncology criteria) who underwent exploratory laparatomy between 1998 and 2005. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use.

Cell extracts

Aqueous cell extracts were prepared as described [15]. Lipid extracts were obtained and dissolved in CDCl3/CD3OD (2:1, v/v) as described [13].

NMR spectroscopy

High-resolution NMR experiments (25°C) were performed at either 400 or 700 MHz (Bruker AVANCE spectrometers, Karlsruhe, Germany). 1H and 31P NMR spectra of aqueous cell extracts were obtained using references, acquisition parameters, data processing and data analysis as described [15,30]. Fully relaxed 1H NMR spectra of lipid extracts were acquired using 30° flip angle, 12.7 s repetition time, 32K time domain data points and 128 transients. Relative PC quantification was performed on the –N+(CH3)3 headgroup signal at 3.22 ppm.

Biochemical assays of PC-cycle enzymes in EOC and EONT cells

Enzyme activities were determined at 25°C by NMR assays specifically developed and validated in our laboratory. Due to the difficulty of obtaining sufficient amounts of OSE cells, hTERT cells were used as EOC non-tumoral counterparts. This choice was justified by the non significant differences in the respective contents of PCho, GPC, free Cho and tCho detected in OSE and hTERT cells [15].

ChoK activity

1H and 31P NMR assays were performed upon addition of exogenous choline chloride, ATP and Mg++ ions to cytosolic cell preparations in Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, as described [15,30].

PC-specific phospholipases and GPC-phosphodiesterase

Cell pellets (15–20 × 106 cells) were resuspended, sonicated and centrifuged as described [30,31] and the assays performed on supernatants using as substrate a monomeric short-chain PC, C6PC, below the critical micellar concentration [32], 5.0 mM in 10 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2 [33].

Choline formation was measured by 1H NMR as product of the following catabolic pathways:

-

1) pld-mediated C6PC hydrolysis

-

a)

and

-

-

2) phosphodiesterase (pd)-mediated hydrolysis of GPC formed by the combined action on C6PC of pla (plA1 and plA2) and lysophospholipases (lpl).

-

b)

plus

-

c)

The overall activity rate of Cho released by the pathways in a) and b) plus c) is here referred to as C6PC-pld*.

The PC-plc activity was determined from the additional increase in Cho production in the same cell lysates as above, in the presence of exogenous alkaline phosphatase (AP), according to the reactions:

- d)

plus - e)

-

For these assays, each cell lysate was divided into four aliquots (15 × 106 cells each), two prepared in the presence or absence of C6PC (to determine, by subtraction, the contribution of endogenous Cho) and two in the presence or absence of AP (to determine the contributions of either pld* or PC-plc activity to the final Cho content).

31P NMR analyses allowed evaluation of differential plA2- and plA1-mediated production from C6PC (0.01 ppm) deacylation of 1-hexanoyl-α-glycerophosphocholine (2-lyso-C6PC; 0.31 ppm) and 2-hexanoyl-α-glycerophosphocholine (1-lyso-C6PC; 0.47 ppm).

The activity of GPC-pd was determined by adding exogenous GPC (5 mM) to the cell lysate, in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2, as previously described [34].

No differences in phospholipase assays were observed in cell lysates incubated in the presence or absence of protease inhibitors, indicating that Cho and PCho were not produced by protein degradation.

Microarray analysis

Gene expression of the enzymes and transporters demonstrated or proposed to be involved in choline metabolism was searched using a dataset generated at INT in an independent study (unpublished data). Human genome U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip (Affymetrix), covering 47,000 transcripts and variants was used. Briefly, total RNA from 8 cell lines and OSE cells (4 different preparations, 1–3 passages at maximum) was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Gibco) and cleaned-up on mini columns (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen). A similar protocol was used for 20 EOC frozen surgical specimens in some experiments, as specified. Total RNA (3 μg) was reverse transcribed, labeled and hybridized to the chip at 45°C for 16 h. After washing, chips were scanned (Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner3000 7G) and images were analyzed using GeneChip Operating Software v1.4 (GCOS1.4). Probe set intensities were calculated using the Microarray Analysis Suite (MAS v5.0, Affymetrix). Data analysis and exploration of probe set intensities levels were performed using Bioconductor open source (http://www.bioconductor.org/) under the R software environment [35]. The reading of probe level data, background correction, normalization by MAS5 “global scaling” procedure and summarizing the probe set values into one expression measure were performed using the affy package. All microarray data are available in Gene Expression Omnibus, accession number GSE19352.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from OSE and IGROV1, SKOV3, OVCAR3 cell lines using the RNAspin Mini Isolation Kit (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by an ABI Prism 7900 HT Sequence detection System (Applied Biosystems) using TaqMan® Gold RT-PCR Reagents. Three independent RNA preparations were reverse transcribed and at least two qPCR reactions were done using each RT product. The pairs of primers and the TaqMan probes for the target mRNAs were from Applied Biosystems, Assay ID: CHKA, Hs00608045_m1; CHKB, Hs00993897_g1; PCYT1A, Hs00192339_m1; PCYT1B, Hs00191464_m1; CHPT1, Hs00220348_m1; PLD1, Hs00160118_m1; PLD2, Hs00160163_m1.

The ΔΔCT method was used to determine the quantity of the target sequences in EOC cell lines relative both to OSE cells (calibrator) and to an endogenous control (GAPDH). Analyses were performed using SDS software 2.2.2 (Applied Biosystems). Expression levels were presented as the relative fold change and calculated as:

Western blotting in cells and tissues

Total cell and tissue lysates were obtained as described [36]. Lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose (Hybond C-Super; Amersham) or polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Immobilon PVDF, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were incubated in 1% nonfat dry milk overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti–PC-PLC antibody [28] or custom-made rabbit polyclonal anti-ChoK antibody [27] or the goat polyclonal antibody anti-ChoK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against β-actin or GAPDH were used as loading controls.

Horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies (Amersham) were added for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoblots were developed using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.). Densitometry analyses were performed with a Bio-Rad apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories Srl) using the Quantity One software or using ImageJ (Wayne Rasband, NIH, Washington, DC).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Software version 3.03 or using JMP software package (Brooks/Cole-Thomson Learning, Belmont, CA). Statistical significance of differences was determined by one-way ANOVA or by Student’s t-test, as specified. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Levels of choline-containing metabolites in EONT and EOC cells

In agreement with our previous study [15], the tCho content in EONT cells was 5.4±0.6 nmol/106 cells, comprising a PCho content of 2.6±0.3 nmol/106 cells (Fig. 1B). Significantly higher tCho (10.3 to 20.3 nmol/106 cells) and PCho levels (8.0 to 14.0 nmol/106 cells) were detected in the set of four analyzed EOC cell lines (Fig. 1B , one-way ANOVA P<0.001). The contribution of PCho to the tCho resonance increased from 53.2±4 % in EONT to 75±5% in EOC cells (P < 0.001), with a resulting decrease in the GPC/PCho ratio. The overall PC content increased 1.3- to 1.6-fold (P<0.04) in EOC compared with EONT cells (Fig. 1C).

Choline transport

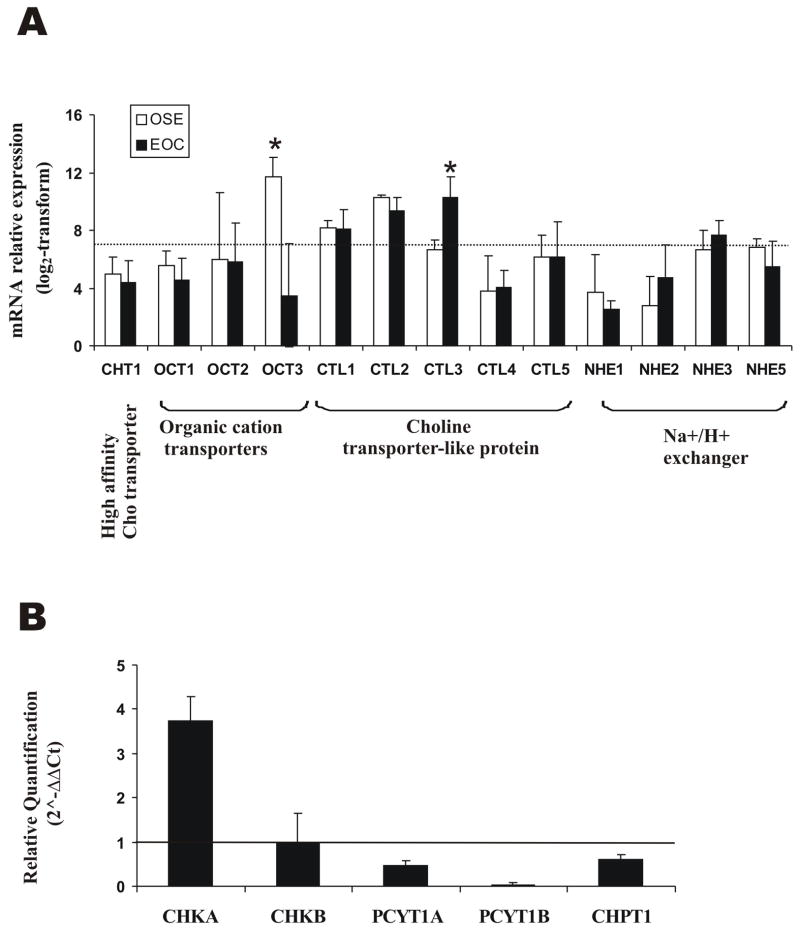

Gene expression analyses of members of the three Cho transporter families [37] showed no differential mRNA levels for the high-affinity Cho transporter CHT1 in EOC compared with OSE cells. Among organic cation transporters, OCT1 and OCT2 remained below the expression threshold, while OCT3, the most highly expressed one, was substantially downregulated in cancer cells (Fig. 2A). Among Cho transporter-like proteins (CTL1-5), only CTL3 showed some increase in mRNA expression in EOC cells. Choline might also be transported by a Cho/H+ antiport system involving Na+/H+ exchangers (NHE) [37] but, in our analysis, the overall expression of NHE1-5 did not reveal any difference between EOC and OSE cells (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Choline transporters and Kennedy pathway enzymes in EOC and EONT cells.

A, Microarray analysis of choline transporters (dotted line, sensitivity threshold). * Significance of differences: P ≤ 0.015; B, RT-qPCR analysis of enzymes’ expression in EOC (OSE cells used as internal calibrator; horizontal line at quantification level = 1). A representative experiment of three performed is shown. For each gene the mean value (± SD) of the analyzed EOC cell lines is reported.

Overexpression and activation of ChoK in EOC cells

The mRNA expression analyses of eight EOC cell lines compared with OSE cells showed ChoKα (CHKA gene) but not ChoKβ (CHKB gene) upregulation (data not shown). Data were independently validated by RT-qPCR on three EOC cell lines (OVCAR3, IGROV1 and SKOV3) compared with three different OSE preparations (Fig. 2B). These results, together with the downregulation of ct (PCYT1A and PCYT1B genes) and pct (CHPT1 gene) in cancer cells (Fig. 2B), point to a major role of ChoKα in the build-up of the PCho pool. Indeed, a significant 2.7±0.3 fold increase in ChoK protein expression was observed by Western blotting of EOC cell lysates (Fig. 3A,B). Also in agreement with our previous study [15], assays on cytosolic preparations (Fig. 3C) showed a 12- to 25-fold ChoK activation in EOC (7.0 to 16.0 nmol/106 cells·h, i.e. 28.5 to 62.3 nmol/mg protein·h) compared with hTERT cells (0.6 ± 0.2 nmol/106 cells·h, i.e. about 3.0 nmol/mg protein·h).

Figure 3. ChoK protein expression and activity.

A, ChoK protein expression by Western blotting, as detected by the custom-made rabbit polyclonal antibody. B, Chok densitometric evaluation referred to GAPDH (mean ± SEM, n≥4. * = P<0.05; ** = P<0.01, relative to EONT by one-way ANOVA. C, Chok activity(mean ± SD, n ≥3).

Activity of PC-specific phospholipases in choline producing PC degradation pathways

PCho production in cancer cells may also derive from phosphorylation of intracellular Cho relased by PC catabolism.

The overall rate of Cho production by PC hydrolytic pathways (defined as pld* activity in Methods) measured in cell lysates in CaCl2 10 mM, was 6.7 ± 0.7 nmol/106 cells·h in EONT cells, increased 2- to 3-fold in IGROV1 and OVCAR3, but remained unaltered in CABAI and SKOV3 (Fig. 4A, white bars).

Figure 4. Enzymes of pld-mediated and deacylation pathways in EOC and EONT cells.

A, pld* and GPC-pd activity(mean value ± SD, n ≥6). B, RT-qPCR analysis of PLD1 and PLD2 in EOC cells (OSE used as internal calibrator; horizontal line at quantification level = 1). A representative experiment of three performed is shown. For each gene mean value ± SD is reported. C, Relative 2-Lyso-C6PC formation (± SD, n ≥3) in EOC and hTERT cell lysates at 1h of exposure to C6PC. D, Gene expression of plA1 and of plA2 isoforms. The dotted line represents sensitivity threshold.

To dissect the individual contributions to the rate of Cho formation (pld*) respectively given by pld and by the deacylation pathway, we performed two types of experiments. GPC-pd assays [34] carried out on cell lysates under the same conditions of ionic strength (CaCl2 10 mM) showed that this enzyme gave only a minor, if any, contribution (max 5–10%) to the rate of Cho production (Fig. 4A, black bars). Therefore, under these conditions, the pld* and pld activity rates were practically identical. We could then conclude that pld was significantly activated (about 2- to 4-fold) only in some (IGROV1 and OVCAR3) but not in all EOC cells. On the other hand, gene expression analyses (not shown) and RT-qPCR experiments (Fig. 4B) performed on pooled EOC compared with EONT cells, did not show differential expression for PLD1 and showed only a moderate, if any, overexpression for the PLD2 gene.

When the GPC-pd assay was performed under optimal conditions of ionic strength (MgCl2 10 mM, pH 7.2 [34]) the rate of Cho production was about 3.8 nmol/106 cells·h in EONT cells, and to increased 2- to 4-fold in some, but not in all EOC cells (Fig. 4A, grey bars). Moreover, since no PCho was formed in the reaction mixture, we could exclude any additional contribution to GPC degradation from the alternative GPC phosphodiesterase.

Regarding the deacylation pathway, 31P NMR analysis of cell lysates in the presence of C6PC (in CaCl2 10mM), showed that the 1-lyso-C6PC level was less than 5% that of 2-lyso-C6PC in both EOC and EONT cells (data not shown) and the content of 2-lyso-C6PC was, at 1 h, significantly lower in cancer cells (Fig. 4C). The concentration of this derivative results from the balance between upstream plA2-mediated C6PC deacylation and downstream lpl-mediated 2-lyso-C6PC degradation into GPC. Since the latter remained below detection at any time point of incubating the cell lysates with C6PC (data not shown), and the GPC-pd activity was very low in CaCl2 10 mM (see above) we concluded that the deacylation pathway was dominated by plA2 and the activity of this enzyme was lower in EOC than in EONT cells. Indeed, mRNA expression analyses showed that PLA1A was practically below the expression threshold in both EONT and EOC cells. Only four out of nineteen PLA2 isoforms appeared to be differentially expressed in EOC compared with EONT cells, but the global difference in overall plA2 expression was not significant (Fig. 4D).

Activation of PC-specific phospholipase C in EOC cells

The activity of PC-plc was about 0.45 ± 0.30 nmol/106 cells·h in EONT cells and increased 5- to 17-fold (one-way ANOVA P<0.03) in the investigated EOC cells (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Activation of PC-plc in EOC cells.

A, PC-plc activity (± SD, n ≥4). B, PC-plc activity and C, PCho content in OVCAR3 cells following incubation in absence (CTRL) or presence of D609 (53 μg/mL, 24 h). Inset: 1H NMR tCho profile in aqueous extracts. D, OVCAR3 cell growth in complete medium in absence (CTRL) or presence of D609 and in serum-deprived medium (-FCS). Error bars, ± SD, n ≥ 5 (Student’s t-test * P<0.05; ***P< 0.001).

Following exposure of OVCAR3 cells to the PC-plc inhibitor D609, the PC-plc activity decreased from 4.3±1.2 to 0.3±0.3 nmol/106 cells·h (n=5, P<0.001) and the average PCho level decreased by 37%±8% (P<0.04) (Fig. 5B and C), while GPC and Cho were not significantly altered. Similar effects were found in SKOV3 cells, in which exposure to D609 induced a PCho decrease of 44% (data not shown). These data provided the first direct demonstration that PC-plc can substantially contribute to PCho accumulation in EOC cells.

Our previous studies showed that cell exposure to D609 induced long-lasting Go/G1 cell cycle arrest in PDGF-stimulated fibroblasts [38] and blocked the S-phase fraction recovery in OVCAR3 cells re-exposed to complete medium after serum depletion [28]. Experiments in the present study showed that incubation with D609 induced a long-lasting (at least up to 72 h) cell proliferation arrest in OVCAR3 cells, an effect comparable with that of FCS deprivation (Fig. 5D).

ChoK and PC-plc detection in clinical specimens

Since upregulation of both ChoK and PC-plc was found in all investigated EOC cell lines, preliminary experiments were conducted to evaluate the expression of these enzymes in a set of EOC surgical specimens. The mRNA relative expression levels of ChoKα measured in clinical tissue samples were significantly higher than those in OSE cells. Overall these levels were, however, lower than those detected in EOC cell lines, (ANOVA analysis for all the three groups, P<0.001) (Fig. 6A). The increased, albeit heterogeneous expression of ChoK was also confirmed at protein level by Western blot analysis of lysates of surgical specimens randomly selected from those analyzed for gene expression (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. ChoK and PC-plc detection in EOC surgical specimens.

A, Gene expression analysis of ChoKα in OSE cells, surgical EOC specimens and EOC cell lines. Horizontal bars represent relative median expression for each group. Western blot analyses of total lysates of EOC surgical specimens and hTERT cells are shown for ChoK protein expression, as detected by the commercially available goat polyclonal antibody (B) and PC-plc protein expression (C). Actin, internal loading control.

Only protein expression data can be at present obtained for PC-plc, whose gene has not yet been identified in mammalian cells. Also the expression of this enzyme was higher (although variable) in lysates of surgical specimens compared with those of EONT cells (see Fig. 6C and ref 28).

Discussion

By combining 1H MRS studies with biochemical assays and mRNA and protein expression analyses, this study showed that the elevated PCho pool in EOC cells primarily resulted from upregulation/activation of two enzymes, ChoK and PC-plc, respectively involved in de novo biosynthesis and PC degradation.

Changes in choline transport and ChoK activity may both be responsible for enhanced radioactive choline uptake and PCho accumulation in cancer cells [15,17,39,40]. These mechanisms have direct implication on choline-based PET examinations [7,8]. Due to reported effects on cell proliferation, choline transport may represent a potential target for therapy [8,17,37]. No differential changes were however observed in mRNA expression of CHT1, OCT or CTL proteins, except for downregulation of OCT2 and moderate upregulation of CTL3 in EOC compared with EONT cells. Further investigations are needed to clarify whether post-transcriptional modifications of choline transporters may contribute to enhance choline uptake by EOC cells [15].

In the Kennedy pathway, ChoKα was over-expressed at mRNA level in EOC cells. Similar or even higher ChoKα upregulation was reported in breast and bladder cancer cell lines [17,26]. The elevated ChoKα expression in these cancer cells suggests an increase in ChoKα/ChoKα at expenses of ChoKα/ChoKβ and ChoKβ/ChoKβ aggregates, a condition reported in liver carcinogenesis [24]. It is worth noting that rather uniform increases in ChoKα mRNA (3.8±0.2 fold) and ChoK protein expression (2.7±0.3-fold) were associated in EOC with a strong and variable amplification (12- to 25-fold) of ChoK activity, which reached the highest values so far reported for epithelial cancer cell lines [17,26]. These results indicate that other factors, likely depending upon oncogene-driven signaling alterations, may influence ChoK activity, in agreement with evidence obtained in other tumor systems [23,41].

Accruing evidence points to the role of ChoK in cell proliferation, transformation and carcinogenesis and supports the use of this enzyme as a novel target for treatment of different types of tumors [22,23,27,41–43]. In fact, a ChoK inhibitor, Mn58b, was found to reduce tumor growth and tCho in human carcinoma models [18,41]. Transient ChoKα down-regulation by small interfering RNA (siRNA-ChoKα) induced cell differentiation, decreased cell proliferation and reduced PCho and tCho levels in breast cancer cells [27]. A combination of siRNA-ChoKα with 5-Fluorouracil resulted in a larger reduction of cell viability/proliferation in breast cancer than in non-tumoral breast epithelial cells [42]. Finally, lentivirus-mediated systemic delivery of the analogous short-hairpin RNA resulted in a significant reduction in tumor growth along with reduced PCho and tCho levels in breast tumor xenografts in vivo [43]. These findings suggest that EOC may also be a candidate for similar treatment strategies.

Among other PC-cycle pathways possibly contributing to PCho accrual, only PC-plc-mediated PC degradation was substantially and consistently activated in all investigated EOC cell lines. In fact, in the deacylation pathway the mRNA expression of nineteen plA2 isoforms was either unaltered or reduced and the overall PlA2 activity decreased in EOC compared with EONT cells, in agreement with the plA2 group IVA underexpression reported for a breast cancer cell line [13]. At the end of the deacylation pathway, a 2- to 4-fold activation of GPC-pd was limited to only some EOC cell lines. Moreover, preliminary results in our laboratory showed unaltered mRNA expression in EOC versus EONT for GDPD5, a glycerol-phosphodiesterase recently indicated as a plausible candidate for mediating GPC-pd activity [44]. Even the activity of pld, an enzyme playing a critical role in cell proliferation and neoplastic processes [45,46], was enhanced in only some of the investigated EOC cells and the average mRNA expression levels of its major isoforms, pld1 and pld2, were substantially unaltered in EOC compared with EONT cells. Similar variable patterns of pld activity and isoforms’ expression were reported in breast cancer cells [17].

A growing evidence indicates a relevant role of PC-plc in mitogenesis, differentiation and apoptosis [38,47–49]. Although isolated from some mammalian cells, this enzyme has not yet been cloned. Evidence of possible PC-plc activation was initially reported by Glunde et al in breast cancer cells [13]. Following detection and characterization of differential subcellular localization of a 66 kDa PC-plc [28], the present study shows 5- to 17-fold increases in PC-plc activity in EOC compared with EONT cells. Furthermore, our preliminary experiments showed that ChoK silencing in breast cancer cells resulted in compensatory PC-plc upregulation, suggesting links between pathways responsible for activation of these two enzymes.1

Inhibition of PC-plc by D609 induced a 30-to-40% decrease in the PCho content of OVCAR3 and SKOV3 cells, providing direct evidence of the contribution of PC-plc activity to the intracellular PCho pool in these cells. This result, together with the antiproliferative effects induced on these cells by D609, point to the possible use of the MRS PCho resonance to monitor the effects of treatments directed against PC-PLC activity in EOC cells. Additional studies are required to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of increased PC-plc activity in ovarian and other cancers. Although a recent study suggests that PC-plc activity may also be conferred by sphingomyelinases (SMase) [50], this mechanism unlikely contributes to PC-plc activation in EOC cells, since PC-plc activity was abolished in OVCAR3 cells by D609, a very poor SMase inhibitor.

The here reported data on upregulation of ChoK and PC-plc in EOC cells, led us to investigate the expression levels of these enzymes in EOC surgical specimens. ChoKα overexpression has been reported and proposed as an indicator of reduced patient survival in human lung and bladder carcinomas [25,26]. Our study shows for the first time that ChoKα mRNA expression, as well as ChoK and PC-plc protein expression, are elevated in EOC surgical specimens. The difference between in vitro and in vivo gene expression levels of ChoKα may derive from stromal contamination and/or from in vitro culture conditions. Independently of absolute levels of gene or protein expression, we can envisage that, upon validation, the parallel detection of ChoKα and PC-plc in the same specimens may facilitate future investigations on their role as predictive or prognostic factors.

In conclusion, the tCho spectral metabolite provides an endogenous reporter on the activity of these enzymes, and can be used to detect and monitor in ovarian cancer the effects of the downregulation or inhibition of these enzymes as novel therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr Massimo Giannini, Ms Paola Alberti, Ms Elena Luison, Ms Tomoyo Takagi and Ms Yelena Mironchik for experienced technical assistance; Dr Carlo Pini and Dr Bianca Barletta for preparation and purification of anti-PC-plc antibodies; Gynecological and Pathological Units of INT-Milan for providing patient materials.

Financial support: AIRC 2007–2010, Special Oncology Programme RO 06.5/N.ISS/Q09, Ministry of Health, Italy and Accordo di Collaborazione Italia-USA ISS/530F/0F29 (FP); Programma Tumori Femminili 2008, Ministry of Health, Italy (SC); NIH P50 CA103175 (KG and ZMB).

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: No conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Glunde K, Mori N, Takagy T, Cecchetti S, Ramoni C, Iorio E, Podo F, Bhujwalla ZM. Choline kinase silencing in breast cancer cells results in compensatory upregulation of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 2008;16, Abstract 244.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negendank WG. Studies of human tumors by MRS: a review. NMR Biomed. 1992;5:303–24. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podo F. Tumour phospholipid metabolism. Review article NMR Biomed. 1999;12:413–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199911)12:7<413::aid-nbm587>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillies RJ, Morse DL. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cancer. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:287–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glunde K, Ackerstaff E, Mori N, Jacobs MA, Bhujwalla ZM. Choline phospholipid metabolism in cancer: consequences for molecular pharmaceutical interventions. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:496–506. doi: 10.1021/mp060067e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podo F, Sardanelli F, Iorio E, et al. Abnormal choline phospholipid metabolism in breast and ovary cancer: molecular bases for noninvasive imaging approaches. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2007;3:123–37. ( http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/ben/cmir/2007)

- 7.Torizuka T, Kanno T, Futatsubashi M, et al. Imaging of gynecologic tumors: Comparison of 11C-choline PET with 18F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1051–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hara T, Bansal A, DeGrado TR. Choline transporter as a novel target for molecular imaging of cancer. Mol Imaging. 2006;5:498–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aboagye EO, Bhujwalla ZM. Malignant transformation alters membrane choline phospholipid metabolism of human mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:80–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackerstaff E, Pflug BR, Nelson JB, Bhujwalla ZM. Detection of increased choline compounds with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy subsequent to malignant transformation of human prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz-Brull R, Seger D, Rivenson-Segal D, Rushkin E, Degani H. Metabolic markers of breast cancer: enhanced choline metabolism and reduced choline-ether-phospholipid synthesis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1966–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mori N, Delsite R, Natarajan K, Kulawiec M, Bhujwalla ZM, Singh KK. Loss of p53 function in colon cancer cells results in increased phosphocholine and total choline. Mol Imaging. 2004;3:319–23. doi: 10.1162/15353500200404121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glunde K, Jie C, Bhujwalla ZM. Molecular causes of the aberrant choline phospholipid metabolism in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4270–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang CK, Li CW, Hsieh TJ, Chien SH, Liu GC, Tsai KB. Characterization of bone and soft-tissue tumors with in vivo 1H MR spectroscopy: initial results. Radiology. 2004;232:599–605. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322031441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iorio E, Mezzanzanica D, Alberti P, Spadaro F, Ramoni C, D’Ascenzo S, Millimaggi D, Pavan A, Dolo V, Canevari S, Podo F. Alterations of choline phospholipid metabolism in ovarian tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9369–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stadlbauer A, Gruber S, Nimsky C, et al. Preoperative grading of gliomas by using metabolite quantification with high-spatial-resolution proton MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology. 2006;3:958–69. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2382041896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eliyahu G, Kreizman T, Degani H. Phosphocholine as a biomarker of breast cancer: molecular and biochemical studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1721–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Saffar NM, Troy H, Ramirez de Molina A, et al. Non invasive magnetic resonance spectroscopic pharmacodynamic markers of the choline kinase inhibitor MN58b in human carcinoma models. Cancer Res. 2006;66:427–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morse DL, Carroll D, Day S, Gray H, Sadarangani P, Murthi S, Job C, Baggett B, Raghunand N, Gillies RJ. Characterization of breast cancers and therapy response by MRS and quantitative gene expression profiling in the choline pathway. NMR Biomed. 2009;22:114–27. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackerstaff E, Glunde K, Bhujwalla ZW. Choline phospholipid metabolism: a target in cancer cells? J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:525–33. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glunde K, Serkova NJ. Therapeutic targets and biomarkers identified in cancer choline phospholipid metabolism. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:1109–23. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.7.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janardhan S, Scrivani P, Sastry N. Choline kinase; An important target for cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1169–86. doi: 10.2174/092986706776360923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramirez de Molina A, Gutierrez R, et al. Increased choline kinase activity in human breast carcinomas: clinical evidence for a potential novel antitumor strategy. Oncogene. 2002;21:4317–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aoyama C, Liao H, Ishidate K. Structure and function of choline kinase isoforms in mammalian cells. Progr Lipid Res. 2004;43:266–81. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramírez de Molina A, Sarmentero-Estrada J, Belda-Iniesta C, Tarón M, Ramírez de Molina V, Cejas P, Skrzypski M, Gallego-Ortega D, de Castro J, Casado E, García-Cabezas MA, Sánchez JJ, Nistal M, Rosell R, González-Barón M, Lacal JC. Expression of choline kinase alpha to predict outcome in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:889–97. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernando E, Sarmentero-Estrada J, Koppie T, Belda-Iniesta C, Ramírez de Molina V, Cejas P, Ozu C, Le C, Sánchez JJ, González-Barón M, Koutcher J, Cordón-Cardó C, Bochner BH, Lacal JC, Ramírez de Molina A. A critical role for choline kinase-alpha in the aggressiveness of bladder carcinomas. Oncogene. 2009;28:2425–35. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glunde K, Raman V, Mori N, Bhujwalla ZM. RNA interference-mediated choline kinase suppression in breast cancer cells induces differentiation and reduces proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:11034–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spadaro F, Ramoni C, Mezzanzanica D, Miotti S, Alberti P, Cecchetti S, Iorio E, Dolo V, Canevari S, Podo F. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C activation in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;16:6541–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramakrishna V, Negri DR, Brusic V, Fontanelli R, Canevari S, Bolis G, Castelli C, Parmiani G. Generation and phenotypic characterization of new human ovarian cancer cell lines with the identification of antigens potentially recognizable by HLA-restricted cytotoxic T cells. Int J Cancer. 1997;73:143–50. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970926)73:1<143::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podo F, Ferretti A, Knijn A, Zhang P, Ramoni C, Barletta B, Pini C, Baccarini S, Pulciani S. Detection of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C in NIH-3T3 fibroblasts and their H-ras transformants: NMR and immunochemical studies. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:1399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomez-Cambronero J, Horwitz J, Sha’afi RI. Measurements of phospholipases A2, C, and D (PLA2, PLC, and PLD). In vitro microassays, analysis of enzyme isoforms, and intact-cell assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;218:155–76. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-356-9:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hergenrother PJ, Martin SF. Determination of the kinetic parameters for phospholipase C (Bacillus cereus) on different phospholipid substrates using a chromogenic assay based on the quantitation of inorganic phosphate. Anal Biochem. 1997;251:45–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris AJ, Frohman MA, Engebrecht J. Measurement of phospholipase D activity. Anal Biochem. 1997;252:1–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Podo F, Carpinelli G, Ferretti A, Borghi P, Proietti E, Belardelli F. Activation of glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase in Friend leukemia cells upon in vitro-induced erytroid differentiation. 31P and 1H NMR studies. Israel J Chem. 1992;32:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bioconductor open source. http://www.bioconductor.org/

- 36.Mezzanzanica D, Balladore E, Turatti F, Luison E, Alberti P, Bagnoli M, Figini M, Mazzoni A, Raspagliesi F, Oggionni M, Pilotti S, Canevari S. CD95-mediated apoptosis is impaired at receptor level by cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein (long form) in wild-type p53 human ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5202–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kouji H, Inazu M, Yamada T, Tajima H, Aoki T, Matsumiya T. Molecular and functional characterization of choline transporter in human colon carcinoma HT-29 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;483:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramoni C, Spadaro F, Barletta B, Dupuis ML, Podo F. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipases C in mitogen-stimulated fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2004;299:370–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshimoto M, Waki A, Obata A, Furukawa T, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Radiolabeled choline as a proliferation marker: comparison with radiolabeled acetate. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:859–65. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nimmagadda S, Glunde K, Pomper MG, Bhujwalla ZM. Pharmacodynamic markers for choline kinase down-regulation in breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2009;11:477–84. doi: 10.1593/neo.81430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramirez de Molina AR, Banez-Coronel M, Gutierrez R, et al. Choline kinase activation is a critical requirement for the proliferation of primary human mammary epithelial cells and breast tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6732–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mori N, Glunde K, Takagi T, Raman V, Bhujwalla ZM. Choline kinase down-regulation increases the effect of 5-fluorouracil in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11284–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krishnamachary B, Glunde K, Wildes F, Mori N, Takagi T, Raman V, Bhujwalla ZM. Noninvasive detection of lentiviral-mediated choline kinase targeting in a human breast cancer xenograft. Cancer Res. 2009;15(69):3464–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallazzini M, Ferraris JD, Burg MB. GDPD5 is a glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase that osmotically regulates the osmoprotective organic osmolyte GPC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11026–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805496105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luquain C, Singh A, Wang L, Natarajan V, Morris AJ. Role of phospholipase D in agonist-stimulated lysophosphatidic acid synthesis by ovarian cancer cells. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1963–75. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300188-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eder AM, Sasagawa T, Mao M, Aoki J, Mills GB. Constitutive and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced LPA production: role of phospholipase D and phospholipase A2. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2482–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Dijk MC, Muriana FJ, de Widt J, Hilkmann H, van Blittezswijk WJ. Involvement of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipases C in platelet-derived growth factor-induced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in Rat-1 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11011–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao J, Zhao B, Wang W, Huang B, Zhang S, Miao J. Phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipases C and ROS were involved in chicken blastodisc differentiation to vascular endothelial cell. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:421–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cifone MG, Rocaioli P, De Maria R, et al. Multiple pathways originated at the Fas/Apo-1 (CD95) receptor: sequential involvement of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C and acidic sphingomyelinase in the propagation of the apoptotic signal. EMBO J. 1995;14:5859–68. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu J, Nilsson A, Jönsson BA, Stenstad H, Agace W, Cheng Y, Duan RD. Intestinal alkaline sphingomyelinase hydrolyses and inactivates platelet-activating factor by a phospholipase C activity. Biochem J. 2006;394:299–308. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]