Abstract

Water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) as a special form of heat radiation with a high tissue penetration and with a low thermal load to the skin surface acts both by thermal and thermic as well as by non-thermal and non-thermic effects. wIRA produces a therapeutically usable field of heat in the tissue and increases tissue temperature, tissue oxygen partial pressure, and tissue perfusion. These three factors are decisive for a sufficient tissue supply with energy and oxygen and consequently as well for wound healing and infection defense.

wIRA can considerably alleviate the pain (with remarkably less need for analgesics) and diminish an elevated wound exudation and inflammation and can show positive immunomodulatory effects. wIRA can advance wound healing or improve an impaired wound healing both in acute and in chronic wounds including infected wounds. Even the normal wound healing process can be improved.

A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study with 111 patients after major abdominal surgery at the University Hospital Heidelberg, Germany, showed with 20 minutes irradiation twice a day (starting on the second postoperative day) in the group with wIRA and visible light VIS (wIRA(+VIS), approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) compared to a control group with only VIS a significant and relevant pain reduction combined with a markedly decreased required dose of analgesics: during 230 single irradiations with wIRA(+VIS) the pain decreased without any exception (median of decrease of pain on postoperative days 2-6 was 13.4 on a 100 mm visual analog scale VAS 0-100), while pain remained unchanged in the control group (p<0.001). The required dose of analgesics was 57-70% lower in the subgroups with wIRA(+VIS) compared to the control subgroups with only VIS (median 598 versus 1398 ml ropivacaine, p<0.001, for peridural catheter analgesia; 31 versus 102 mg piritramide, p=0.001, for patient-controlled analgesia; 3.4 versus 10.2 g metamizole, p=0.005, for intravenous and oral analgesia). During irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) the subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure rose markedly by approximately 30% and the subcutaneous temperature by approximately 2.7°C (both in a tissue depth of 2 cm), whereas both remained unchanged in the control group: after irradiation the median of the subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure was 41.6 (with wIRA) versus 30.2 mm Hg in the control group (p<0.001), the median of the subcutaneous temperature was 38.9 versus 36.4°C (p<0.001). The overall evaluation of the effect of irradiation, including wound healing, pain and cosmesis, assessed on a VAS (0-100 with 50 as indifferent point of no effect) by the surgeon (median 79.0 versus 46.8, p<0.001) or the patient (79.0 versus 50.2, p<0.001) was markedly better in the group with wIRA compared to the control group. This was also true for single aspects: Wound healing assessed on a VAS by the surgeon (median 88.6 versus 78.5, p<0.001) or the patient (median 85.8 versus 81.0, p=0.040, trend) and cosmetic result assessed on a VAS by the surgeon (median 84.5 versus 76.5, p<0.001) or the patient (median 86.7 versus 73.6, p=0.001). In addition there was a trend in favor of the wIRA group to a lower rate of total wound infections (3 of 46, approximately 7%, versus 7 of 48, approximately 15%, p=0.208) including late infections after discharge, caused by the different rate of late infections after discharge: 0 of 46 in the wIRA group and 4 of 48 in the control group. And there was a trend towards a shorter postoperative hospital stay: 9 days in the wIRA group versus 11 days in the control group (p=0.037). The principal finding of this study was that postoperative irradiation with wIRA can improve even a normal wound healing process.

A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study with 45 severely burned children at the Children’s Hospital Park Schönfeld, Kassel, Germany, showed with 30 minutes irradiation once a day (starting on the first day, day of burn as day 1) in the group with wIRA and visible light VIS (wIRA(+VIS), approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) compared to a control group with only VIS a markedly faster reduction of wound size. On the fifth day (after 4 days with irradiation) decision was taken, whether surgical debridement of necrotic tissue was necessary because of deeper (second degree, type b) burns (11 of 21 in the group with wIRA, 14 of 24 in the control group) or non-surgical treatment was possible (second degree, type a, burns). The patients treated conservatively were kept within the study and irradiated till complete reepithelialization. The patients in the group with wIRA showed a markedly faster reduction of wound area: a median reduction of wound size of 50% was reached already after 7 days compared to 9 days in the control group, a median reduction of wound size of 90% was already achieved after 9 days compared to 13 days in the control group. In addition the group with wIRA showed superior results till 3 months after the burn in terms of the overall surgical assessment of the wound, cosmesis, and assessment of effects of irradiation compared to the control group.

In a prospective, randomized, controlled study with 12 volunteers at the University Medical Center Charité, Berlin, Germany, within each volunteer 4 experimental superficial wounds (5 mm diameter) as an acute wound model were generated by suction cup technique, removing the roof of the blister with a scalpel and a sterile forceps (day 1). 4 different treatments were used and investigated during 10 days: no therapy, only wIRA(+VIS) (approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS; 30 minutes irradiation once a day), only dexpanthenol (= D-panthenol) cream once a day, wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream once a day. Healing of the small experimental wounds was from a clinical point of view excellent with all 4 treatments. Therefore there were only small differences between the treatments with slight advantages of the combination wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream and of dexpanthenol cream alone concerning relative change of wound size and assessment of feeling of the wound area. However laser scanning microscopy with a scoring system revealed differences between the 4 treatments concerning the formation of the stratum corneum (from first layer of corneocytes to full formation) especially on the days 5-7: fastest formation of the stratum corneum was seen in wounds treated with wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream, second was wIRA(+VIS) alone, third dexpanthenol cream alone and last were untreated wounds. Bacterial counts of the wounds (taken every 2 days) showed, that wIRA(+VIS) and the combination of wIRA(+VIS) with dexpanthenol cream were able to inhibit the colonisation with physiological skin flora up to day 5 when compared with the two other groups (untreated group and group with dexpanthenol cream alone). At any investigated time, the amount of colonisation under therapy with wIRA(+VIS) alone was lower (interpreted as more suppressed) compared with the group with wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream.

During rehabilitation after hip and knee endoprosthetic operations the resorption of wound seromas and wound hematomas was both clinically and sonographically faster and pain was reduced by irradiation with wIRA(+VIS).

wIRA can be used successfully for persistent postoperative pain e.g. after thoracotomy.

As perspectives for wIRA it seems clinically prudent to use wIRA both pre- and postoperatively, e.g. in abdominal and thoracic operations. wIRA can be used preoperatively (e.g. during 1-2 weeks) to precondition donor and recipient sites of skin flaps, transplants or partial-thickness skin grafts, and postoperatively to improve wound healing and to decrease pain, inflammation and infections at all mentioned sites. wIRA can be used to support routine pre- or intraoperative antibiotic administration or it might even be discussed to replace this under certain conditions by wIRA.

Keywords: water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA); wound healing; acute wounds; prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind studies; reduction of pain; problem wounds; wound infections; infection defense; wound exudation; inflammation; thermal and non-thermal effects; thermic and non-thermic effects; energy supply; oxygen supply; tissue oxygen partial pressure; tissue temperature; tissue blood flow; visual analog scales (VAS); quality of life

Abstract

Wassergefiltertes Infrarot A (wIRA) als spezielle Form der Wärmestrahlung mit hohem Eindringvermögen in das Gewebe bei geringer thermischer Oberflächenbelastung wirkt sowohl über thermische und temperaturabhängige als auch über nicht-thermische und temperaturunabhängige Effekte. wIRA erzeugt ein therapeutisch nutzbares Wärmefeld im Gewebe und steigert Temperatur und Sauerstoffpartialdruck im Gewebe sowie die Gewebedurchblutung. Diese drei Faktoren sind entscheidend für eine ausreichende Versorgung des Gewebes mit Energie und Sauerstoff und deshalb auch für Wundheilung und Infektionsabwehr.

wIRA vermag Schmerzen deutlich zu mindern (mit bemerkenswert niedrigerem Analgetikabedarf) und eine erhöhte Wundsekretion und Entzündung herabzusetzen sowie positive immunmodulierende Effekte zu zeigen. wIRA kann sowohl bei akuten als auch bei chronischen Wunden einschließlich infizierter Wunden die Wundheilung beschleunigen oder bei stagnierender Wundheilung verbessern. Selbst der normale Wundheilungsprozess kann verbessert werden.

Eine prospektive, randomisierte, kontrollierte, doppeltblinde Studie mit 111 Patienten nach großen abdominalen Operationen in der Chirurgischen Universitätsklinik Heidelberg in Deutschland zeigte mit 20 Minuten Bestrahlung zweimal am Tag (beginnend am zweiten postoperativen Tag) in der Gruppe mit wIRA und sichtbarem Licht VIS (wIRA(+VIS), ungefähr 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) verglichen mit der Kontrollgruppe mit nur VIS eine signifikante und relevante Schmerzminderung verbunden mit einer deutlich verminderten erforderlichen Analgetikadosis: während 230 einzelner Bestrahlungen mit wIRA(+VIS) nahm der Schmerz ausnahmslos ab (der Median der Schmerzminderung an den postoperativen Tagen 2-6 betrug 13,4 auf einer 100 mm visuellen Analogskala VAS 0-100), während der Schmerz in der Kontrollgruppe unverändert blieb (p<0,001). Die erforderliche Analgetikadosis war in den Untergruppen mit wIRA(+VIS) 57-70% niedriger im Vergleich zu den Kontrolluntergruppen mit nur VIS (Median 598 versus 1398 ml Ropivacain, p<0,001, für Peridural-Katheter-Analgesie; 31 versus 102 mg Piritramid, p=0,001, for patientenkontrollierte Analgesie; 3,4 versus 10,2 g Metamizol, p=0,005, für intravenöse und orale Analgesie). Während der Bestrahlung mit wIRA(+VIS) stieg der subkutane Sauerstoffpartialdruck wesentlich um ungefähr 30% und die subkutane Temperatur um ungefähr 2,7°C an (beides in 2 cm Gewebetiefe), während beide in der Kontrollgruppe unverändert blieben: nach Bestrahlung lag der Median des subkutanen Sauerstoffpartialdrucks bei 41,6 (mit wIRA) versus 30,2 mm Hg in der Kontrollgruppe (p<0,001), der Median der subkutanen Temperatur bei 38,9 versus 36,4°C (p<0,001). Die Gesamtbeurteilung des Effekts der Bestrahlung einschließlich Wundheilung, Schmerzen und kosmetischem Ergebnis, erhoben mit einer VAS (0-100 mit 50 als Indifferenzpunkt ohne Effekt) durch den Chirurgen (Median 79,0 versus 46,8, p<0,001) oder den Patienten (79,0 versus 50,2, p<0,001) war in der Gruppe mit wIRA wesentlich besser verglichen mit der Kontrollgruppe. Dies galt auch für die einzelnen Aspekte: Wundheilung, erhoben mit einer VAS durch den Chirurgen (Median 88,6 versus 78,5, p<0,001) oder den Patienten (Median 85,8 versus 81,0, p=0,040, Trend), und kosmetisches Ergebnis, erhoben mit einer VAS durch den Chirurgen (Median 84,5 versus 76,5, p<0,001) oder den Patienten (Median 86,7 versus 73,6, p=0,001). Außerdem zeigte sich ein Trend zugunsten der wIRA-Gruppe hin zu einer niedrigeren Rate von Wundinfektionen insgesamt (3 von 46, ungefähr 7%, versus 7 von 48, ungefähr 15%, p=0,208) einschließlich später Infektionen nach der Entlassung, hervorgerufen durch eine unterschiedliche Rate von späten Infektionen nach der Entlassung: 0 von 46 in der wIRA-Gruppe und 4 of 48 in der Kontrollgruppe. Und es gab einen Trend hin zu einem kürzeren postoperativen Krankenhausaufenthalt: 9 Tage in der wIRA-Gruppe versus 11 Tage in der Kontrollgruppe (p=0,037). Das Hauptergebnis der Studie war, dass postoperative Bestrahlung mit wIRA selbst einen normalen Wundheilungsprozess verbessern kann.

Eine prospektive, randomisierte, kontrollierte, doppelt-blinde Studie mit 45 schwerbrandverletzten Kindern im Kinderkrankenhaus Park Schönfeld, Kassel, Deutschland, zeigte mit täglich 30 Minuten Bestrahlung (ab dem ersten Tag, Tag der Verbrennung als Tag 1) in der Gruppe mit wIRA und sichbarem Licht VIS (wIRA(+VIS), ungefähr 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) verglichen mit einer Kontrollgruppe mit nur VIS eine deutlich schnellere Abnahme der Wundfläche. Am fünften Tag (nach 4 Tagen mit Bestrahlung) wurde entschieden, ob ein chirurgisches Debridement nekrotischen Gewebes wegen tieferer (Grad 2b) Verbrennungen notwendig war (11 von 21 in der Gruppe mit wIRA, 14 von 24 in der Kontrollgruppe) oder eine konservative Behandlung möglich war (Verbrennungen vom Grad 2a). Die Patienten mit konservativer Behandlung wurden in der Studie weitergeführt und bis zur vollständigen Reepithelisierung bestrahlt. Die Patienten in der Gruppe mit wIRA zeigten eine deutlich schnellere Abnahme der Wundfläche: eine Abnahme der Wundfläche im Median um 50% wurde bereits nach 7 Tagen verglichen mit 9 Tagen in der Kontrollgruppe und eine Abnahme der Wundfläche im Median um 90% wurde nach 9 Tagen verglichen mit 13 Tagen in der Kontrollgruppe erreicht. Außerdem zeigte die Gruppe mit wIRA bessere Ergebnisse bis 3 Monate nach der Verbrennung hinsichtlich der chirurgischen Gesamteinschätzung der Wunde, hinsichtlich des kosmetischen Ergebnisses und hinsichtlich der Einschätzung des Effekts der Bestrahlung verglichen mit der Kontrollgruppe.

In einer prospektiven, randomisierten, kontrollierten Studie mit 12 Probanden an der Universitätsklinik Charité, Berlin, Deutschland, wurden bei jedem Probanden 4 experimentelle oberflächliche Wunden (5 mm Durchmesser) als ein Modell für akute Wunden mittels Saugblasentechnik und Entfernen des Blasendachs mit Skalpell und steriler Pinzette erzeugt (Tag 1). 4 verschiedene Behandlungsarten wurden während 10 Tagen angewendet und untersucht: keine Therapie, nur wIRA(+VIS) (ungefähr 75% wIRA, 25% VIS; täglich 30 Minuten Bestrahlung), nur Dexpanthenol-Salbe (= D-Panthenol-Salbe) einmal täglich, wIRA(+VIS) und Dexpanthenol-Salbe einmal täglich. Die Heilung der kleinen experimentellen Wunden war aus klinischer Sicht bei allen 4 Behandlungsarten sehr gut. Deshalb gab es nur kleine Unterschiede zwischen den Behandlungsarten mit kleinen Vorteilen für die Kombination wIRA(+VIS) und Dexpanthenol-Salbe und für nur Dexpanthenol-Salbe hinsichtlich der relativen Änderung der Wundfläche und der Einschätzung des Empfindens des Wundgebietes. Laser-Scan-Mikroskopie mit einem Score-System zeigte jedoch Unterschiede zwischen den 4 Behandlungsarten hinsichtlich der Bildung des Stratum corneum (von der ersten Schicht von Korneozyten bis zur vollen Ausbildung) insbesondere für die Tage 5-7: die schnellste Ausbildung des Stratum corneum wurde bei Wunden beobachtet, die mit wIRA(+VIS) und Dexpanthenol-Salbe behandelt wurden, am zweitschnellsten war wIRA(+VIS) alleine, an dritter Stelle lag Dexpanthenol-Salbe allein und an letzter Stelle waren die unbehandelten Wunden. Keimzahlbestimmungen der Wunden (alle 2 Tage erhoben) zeigten, dass wIRA(+VIS) und die Kombination von wIRA(+VIS) mit Dexpanthenol-Salbe in der Lage waren, die Kolonisation mit physiologischer Hautflora bis zum Tag 5 im Vergleich zu den beiden anderen Gruppen (untherapierte Gruppe und Gruppe mit nur Dexpanthenol-Salbe) zu verhindern. Zu allen untersuchten Zeitpunkten war das Maß an Kolonisation unter Therapie mit wIRA(+VIS) allein niedriger (mehr supprimiert) als in der Gruppe mit wIRA(+VIS) und Dexpanthenol-Salbe.

Während der Rehabilitation nach Hüft- und Knie-Endoprothesen-Operationen war durch Bestrahlung mit wIRA(+VIS) die Resorption von Wundseromen und Wundhämatomen sowohl klinisch als auch sonographisch schneller und die Schmerzen waren reduziert.

wIRA kann erfolgreich bei persistierenden postoperativen Schmerzen z.B. nach Thorakotomie eingesetzt werden.

Als Perspektiven für wIRA erscheint es klinisch sinnvoll, wIRA sowohl prä- als auch postoperativ z.B. bei abdominellen und thorakalen Operationen einzusetzen. wIRA kann präoperativ (z.B. während 1-2 Wochen) zur Präkonditionierung der Entnahme- und der Empfängerstellen von Hautlappen, Transplantaten oder Spalthauttransplantaten und postoperativ zum Verbessern der Wundheilung und zum Mindern von Schmerz, Entzündung und Infektion an allen genannten Stellen verwendet werden. wIRA kann zum Unterstützen einer prä- oder postoperativen Routine-Antibiotika-Gabe eingesetzt werden oder es könnte auch diskutiert werden, dies unter bestimmten Umständen durch wIRA zu ersetzen.

General aspects of wIRA for the improvement of wound healing in dermatology and surgery

Principles and working mechanisms (thermal and thermic effects, non-thermal and non-thermic effects) of water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) related to wound healing and fundamental recommendations for the clinical use of wIRA and safety aspects are presented in detail in [1] and [2], see especially review [1].

The typical main clinical effects of wIRA (both true in acute and in chronic wounds) are:

wIRA increases

tissue temperature

tissue oxygen partial pressure

tissue perfusion.

wIRA decreases

pain (and consequently the required dose of pain medication)

inflammation

hypersecretion.

wIRA has

positive immunomodulatory effects.

wIRA improves and advances

wound healing (even the normal wound healing process).

wIRA shortens

time till complete wound healing and hospital stay.

And especially in chronic wounds:

wIRA can enable wound healing in non-healing wounds.

Tissue temperature [3], [4], [5], [6], tissue oxygen partial pressure [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], and tissue perfusion are decisive factors for a sufficient tissue supply with energy and oxygen and consequently as well for wound healing and infection defense, see review in [1], [2].

wIRA can increase tissue temperature [5], [6], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], tissue oxygen partial pressure [5], [24], and tissue perfusion [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], see review in [1], [2].

wIRA in clinical use at appropriate irradiances has been described as helpful and safe [5], [6], [10], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], review in [1], [2], and with possible protective cellular effects [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50].

Acute wounds and especially chronic wounds, non-healing wounds or infected problem wounds should be irradiated with wIRA ideally once or twice per day for (20-)30 minutes each (longer irradiation times per day are possible and often helpful), at least three times per week for (20-)30 minutes [1], [2]. wIRA does not replace other sensible/necessary therapeutic procedures but complementes them. Correspondingly the therapy with wIRA has to be embedded in an overall therapeutic concept. wIRA can be used independently from therapy preferences concerning wound management (e.g. moist wound management). Typically for wIRA irradiation the wound has to be uncovered, as most bandages or wound dressings (with the exception of e.g. some tested transparent foils) are not adequately permeable for wIRA [1], [2].

According to modern concepts [51] for the assessment of wound healing also other end-points and variables of interest aside from a complete wound closure have to be used like reduction of pain, improvement of quality of life, improvement of the cosmetic result, reduction of scars, clinically relevant shortening of the time of wound healing and improved quality of healing [2]. Nowadays great importance is placed on the reduction or avoidance of pain in order to improve the wound healing and to avoid the formation of a pain memory with chronification of the pain [52], [53] associated with the application of management strategies of common acute and chronic wounds.

Up to now 6 prospective clinical studies with wIRA concerning wound healing have been performed, 3 with acute wounds (presented here), 3 with chronic wounds (presented in [54]).

wIRA for acute operation wounds (Study of the University Hospital Heidelberg, Department of Surgery)

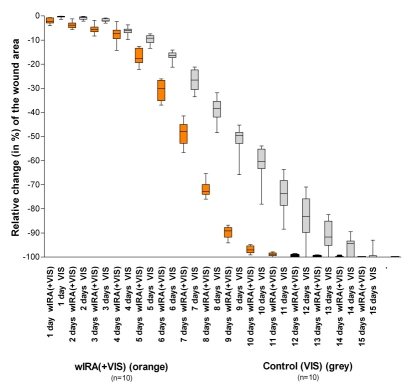

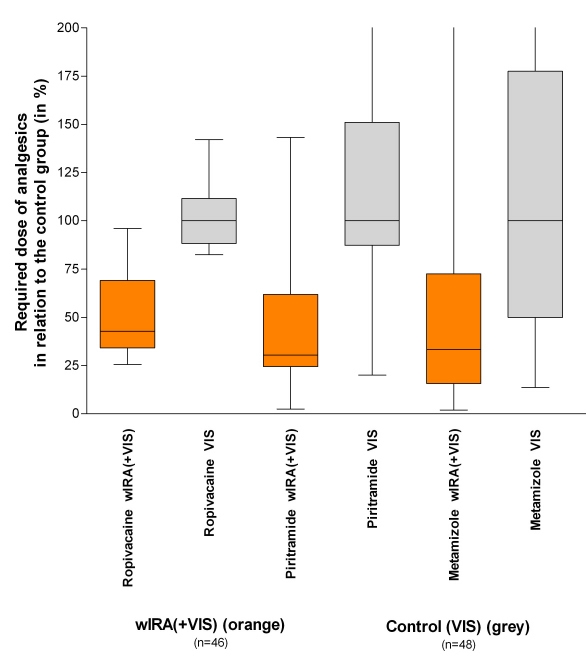

A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study with 111 patients (94 were finally included) after major abdominal surgery at the University Hospital Heidelberg, Germany, Department of Surgery, showed with 20 minutes irradiation twice a day (starting on the second postoperative day) in the group with wIRA and visible light VIS (wIRA(+VIS), approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) compared to a control group with only VIS a significant and relevant pain reduction combined with a markedly decreased required dose of analgesics: Remarkably during 230 single irradiations with wIRA(+VIS) the pain decreased without any exception (median of decrease of pain on postoperative days 2-6 was 13.4 on a 100 mm visual analog scale VAS 0-100), while pain remained unchanged in the control group (p<0.001, significant) (see Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). The required dose of analgesics was 57-70% lower in the subgroups with wIRA(+VIS) compared to the control subgroups with only VIS (median 598 versus 1398 ml ropivacaine, p<0.001, for peridural catheter analgesia; 31 versus 102 mg piritramide, p=0.001, for patient-controlled analgesia; 3.4 versus 10.2 g metamizole, p=0.005, for intravenous and oral analgesia, see Figure 2 (Fig. 2)) [5].

Figure 1. Decrease of postoperative pain during irradiation in the group with water-filtered infrared-A and visible light (wIRA(+VIS)) and in the control group with only visible light (VIS) .

(assessed with a visual analog scale; given as minimum, percentiles of 25, median, percentiles of 75, and maximum (box and whiskers graph with the box representing the interquartile range), adapted from [5]).

Remarkably during 230 single irradiations with wIRA(+VIS) the pain decreased without any exception, while pain remained unchanged in the control group (p<0.001, significant).

Figure 2. Required dose of analgesics of the subgroups with water-filtered infrared-A and visible light (wIRA(+VIS)) in relation to the control subgroups with only visible light (VIS) .

(medians of the control subgroups = 100) (given as minimum, percentiles of 25, median, percentiles of 75, and maximum (box and whiskers graph with the box representing the interquartile range), data taken from [5]).

The required dose of analgesics was 57-70% lower in the subgroups with wIRA(+VIS) compared to the control subgroups with only VIS.

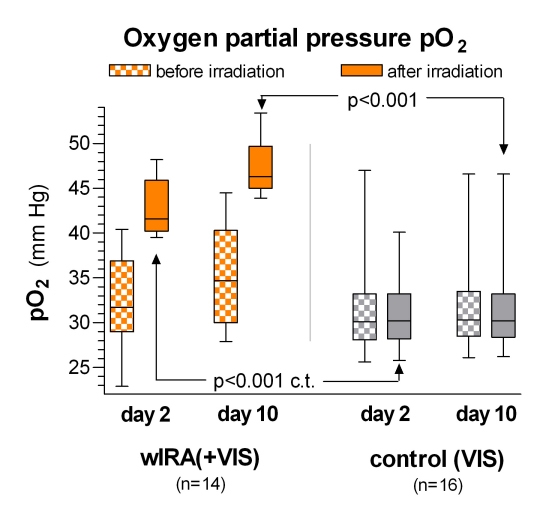

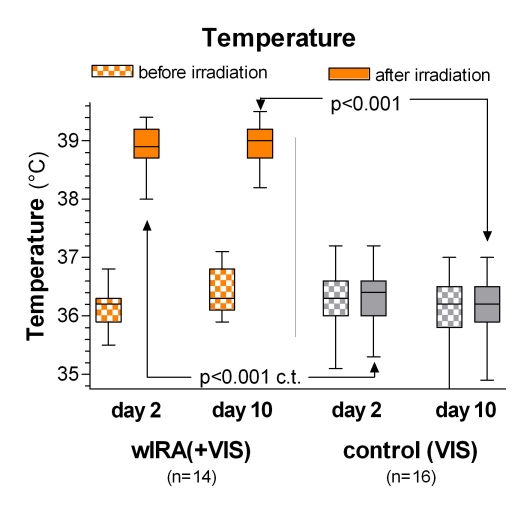

During irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) the subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure rose markedly by approximately 30% and the subcutaneous temperature by approximately 2.7°C (both in a tissue depth of 2 cm), whereas both remained unchanged in the control group: after irradiation the median of the subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure was 41.6 (with wIRA) versus 30.2 mm Hg in the control group (p<0.001, significant, see Figure 3 (Fig. 3)), the median of the subcutaneous temperature was 38.9 versus 36.4°C (p<0.001, significant, see Figure 4 (Fig. 4)). There was a trend towards increased subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure, both before and after irradiation, from the second to the tenth postoperative day in the group with wIRA (see Figure 3 (Fig. 3)) as a sign of persistent effects of wIRA on the tissue, at least lasting for more than 12 hours [5].

Figure 3. Subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure in 2 cm depth of tissue on the postoperative days 2 and 10 in the group with water-filtered infrared-A and visible light (wIRA(+VIS)) and in the control group with only visible light (VIS) .

(given as minimum, percentiles of 25, median, percentiles of 75, and maximum (box and whiskers graph with the box representing the interquartile range); c.t.: confirmatory test (Mann-Whitney U test); adapted from [5]).

During irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) the subcutaneous oxygen partial pressure rose markedly by approximately 30%, whereas it remained unchanged in the control group.

Figure 4. Subcutaneous temperature in 2 cm depth of tissue on the postoperative days 2 and 10 in the group with water-filtered infrared-A and visible light (wIRA(+VIS)) and in the control group with only visible light (VIS) .

(given as minimum, percentiles of 25, median, percentiles of 75, and maximum (box and whiskers graph with the box representing the interquartile range); c.t.: confirmatory test (Mann-Whitney U test); adapted from [5]).

During irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) the subcutaneous temperature rose markedly by approximately 2.7°C, whereas it remained unchanged in the control group.

The overall evaluation of the effect of irradiation, including wound healing, pain and cosmesis, assessed on a VAS (0-100 with 0 representing maximal negative effect, 50 as indifferent point of no effect and 100 representing maximal positive effect) by the surgeon (median 79.0 versus 46.8, p<0.001) or the patient (79.0 versus 50.2, p<0.001) was markedly better in the group with wIRA compared to the control group [5].

This was also true for single aspects:

Wound healing assessed on a VAS by the surgeon (median 88.6 versus 78.5, p<0.001, significant) or the patient (median 85.8 versus 81.0, p=0.040, trend) [5],

Cosmetic result assessed on a VAS by the surgeon (median 84.5 versus 76.5, p<0.001) or the patient (median 86.7 versus 73.6, p=0.001) [5].

In addition there was a trend in favor of the wIRA group to a lower rate of total wound infections (3 of 46, approximately 7%, versus 7 of 48, approximately 15%, p=0.208) including late infections after discharge, caused by the different rate of late infections after discharge: 0 of 46 in the wIRA group and 4 of 48 in the control group [5].

And there was a trend towards a shorter postoperative hospital stay: 9 days in the wIRA group versus 11 days in the control group (p=0.037) [5].

(Regarding the necessity of an alpha error adjustment in multiple testing, in [5] five p-values are presented confirmatively, see e.g. Figure 3 (Fig. 3) and Figure 4 (Fig. 4), and the other p-values in a descriptive sense.)

The principal finding of this study was that postoperative irradiation with wIRA can improve even a normal wound healing process [2], [5], [29], [30].

As both groups received irradiation with visible light and no placebo effects were observed (no acute changes in objective and subjective variables during irradiation in the control group), the acute changes in the wIRA group were attributed to wIRA within the irradiation [5].

In accordance with [1] and [2] the effects of wIRA are explained in [5] as thermal and non-thermal effects (see [1]). wIRA improves factors involved in energy production: tissue oxygen partial pressure, perfusion and temperature. As non-thermal effects are mentioned the direct stimulation of cells causing immunomodulation or improvement of wound healing, and the influence on adhesive interactions between cells and extracellular matrices [55], which have a regulatory role in wound repair processes [5]. Pain relief by wIRA is explained both by thermal and non-thermal effects: increased perfusion allows better elimination of accumulated metabolites, such as pain mediators, lactic acid and bacterial toxins, and increases metabolism; non-thermal effects include direct effects on cells and possibly on nociceptors [5]. Other cross effects are mentioned in [5]: Pain reduction by wIRA leads to a reduced required dose of analgesics and consequently to decreased sedation and to better bowel movement. Pain reduction by wIRA may support its vasodilatory effect and may decrease the risk of wound infection, as adequate control of postoperative pain increases oxygen partial pressure and decreases by this the risk of infection markedly [5], [56], [57]. An increased oxygen partial pressure can influence positively the concentration and receptor density of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the wound, resulting in accelerated healing by increased blood vessel growth [5], [58].

The effects of wIRA (increased oxygen partial pressure) and antibiotics are presumably synergistic, as antibiotics are less effective in hypoxic tissue [5], [59], [60].

The shorter postoperative hospital stay with the application of wIRA and the tendency towards lower infection rates are expected to lead to substantial reductions in average hospital costs [5].

The reduced degree of pain during wIRA treatment, the decreased need for pain medication, better wound healing, and shorter hospital stay might explain the markedly better overall assessment for the entire treatment period recorded before discharge by patients treated with wIRA, reflecting a better quality of life [5].

wIRA for severely burned children (Study of the Children’s Hospital Park Schönfeld, Kassel, Department of Pediatric Surgery)

A prospective, randomized, controlled, double-blind study with 45 severely burned children at the Children’s Hospital Park Schönfeld, Kassel, Germany, Department of Pediatric Surgery, showed with 30 minutes irradiation once a day (starting on the first day, day of burn as day 1) in the group with wIRA and visible light VIS (wIRA(+VIS), approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS) compared to a control group with only VIS a markedly faster reduction of wound size [32]. On the fifth day (after 4 days with irradiation) decision was taken, whether surgical debridement of necrotic tissue was necessary because of deeper (second degree, type b) burns (11 of 21 in the group with wIRA, 14 of 24 in the control group) or non-surgical treatment was possible (second degree, type a, burns) (10 of 21, 47%, in the group with wIRA; 10 of 24, 42%, in the control group). The patients treated conservatively were kept within the study and irradiated until complete cutaneous regeneration (complete reepithelialization) occurred.

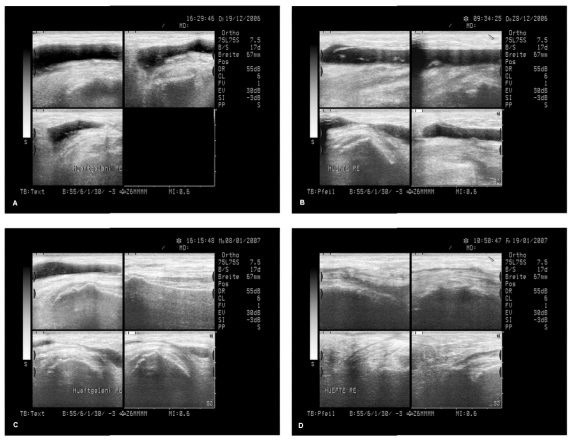

The relative change of the wound size is presented in Figure 5 (Fig. 5): over the whole period of time at any day the relative reduction (in %) of the wound area (related to the size at the beginning) was larger in the group with wIRA compared to the control group, which means the patients in the group with wIRA showed a markedly faster reduction of wound area: a median reduction of wound size of 50% was reached in the group with wIRA already after 7 days compared to 9 days in the control group, a median reduction of wound size of 90% was already achieved after 9 days compared to 13 days in the control group, which are relevant advantages concerning time [32]. In addition the group with wIRA showed superior results till 3 months after the burn in terms of the overall surgical assessment of the wound, cosmesis, and assessment of effects of irradiation compared to the control group [32]. E.g. the median of the assessed effect of irradiation (VAS 0-100 with 0 representing maximal negative effect, 50 as indifferent point of no effect and 100 representing maximal positive effect) on days 7-9 was 58 versus 50 (no placebo effect in the control group), after 3 months 65 versus 56. The hospital stay was slightly shorter in the group with wIRA compared to the control group. These results are in accordance with the findings of the above described study of the University Hospital Heidelberg, Department of Surgery.

Figure 5. Relative change of wound area of severely burned children .

depending on duration of treatment (in days) in the group with water-filtered infrared-A and visible light (wIRA(+VIS)) and in the control group with only visible light (VIS)

(given as minimum, percentiles of 25, median, percentiles of 75, and maximum (box and whiskers graph with the box representing the interquartile range), from [32]).

Fig. 5 presents the data from those 10+10 = 20 children (out of 21+24 = 45 children), who had second degree, type a, burns (not second degree, type b, burns) and were consequently treated non-surgically until complete cutaneous regeneration occurred including irradiation (starting at the day of the burn, till complete reepithelialization) with wIRA(+VIS) or with only VIS (control group).

Patients in the group with wIRA showed a markedly faster reduction of wound area compared to the control group: a median reduction of wound size of 50% was reached in the group with wIRA already after 7 days compared to 9 days in the control group, a median reduction of wound size of 90% was achieved in the group with wIRA already after 9 days compared to 13 days in the control group.

Examples of rapid improvement of wound healing with wIRA are presented in Figure 6 (Fig. 6) and Figure 7 (Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Example of a rapid improvement with wIRA in a severely burned child .

Left: 1 day after the burn, right: only 30 hours later as shown on the left side (from [32]).

Figure 7. Example of a rapid improvement with wIRA in a severely burned child .

Left: before irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) (shortly after admission to the hospital), right: after 2 irradiations with wIRA(+VIS), only 40 hours later as pictured on the left (from [32]).

wIRA for experimental wounds (Study of the University Medical Center Charité Berlin, Department of Dermatology)

In a prospective, randomized, controlled study with 12 volunteers at the University Medical Center Charité, Berlin, Germany, Department of Dermatology, Center of Experimental and Applied Cutaneous Physiology, within each volunteer 4 experimental superficial wounds (5 mm diameter) as an acute wound model were generated by suction cup technique, removing the roof of the blister with a scalpel and a sterile forceps (day 1). 4 different treatments were used and investigated during 10 days: no therapy, only wIRA(+VIS) (approximately 75% wIRA, 25% VIS; 30 minutes irradiation once a day), only dexpanthenol (= D-panthenol) cream once a day, wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream once a day.

Healing of the small experimental wounds was from a clinical point of view excellent with all 4 treatments. Therefore there were only small differences between the treatments with slight advantages of the combination wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream and of dexpanthenol cream alone concerning relative change of wound size and assessment of feeling of the wound area. However laser scanning microscopy with a scoring system as described in [61] revealed differences between the 4 treatments concerning the formation of the stratum corneum (from first layer of corneocytes to full formation) especially on the days 5-7: fastest formation of the stratum corneum was seen in wounds treated with wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream, second was wIRA(+VIS) alone, third dexpanthenol cream alone and last were untreated wounds.

Bacterial counts of the wounds were taken every 2 days until day 9 (4 follow-up samples per wound): wIRA(+VIS) and the combination of wIRA(+VIS) with dexpanthenol cream were able to inhibit the colonisation with physiological skin flora up to day 5 when compared with the two other groups (untreated group and group with dexpanthenol cream alone). All groups developed colonisation peaks at day 7 and an ensuing decline of colonisation at the time of wound closure (day 9). At any investigated time, the amount of colonisation under therapy with wIRA(+VIS) alone was lower (interpreted as more suppressed) compared with the group with wIRA(+VIS) and dexpanthenol cream. It can be interpreted, that among the tested therapies wIRA(+VIS) led to disadvantageous conditions for bacteria.

wIRA for wound seromas

The investigation of a preliminary group ahead of a formerly planned prospective randomized, controlled, blinded study concerning wIRA during rehabilitation after hip and knee endoprosthetic operations revealed both clinically and sonographically a faster resorption of wound seromas and wound hematomas and a reduction of pain by irradiation with wIRA(+VIS) [2], [62].

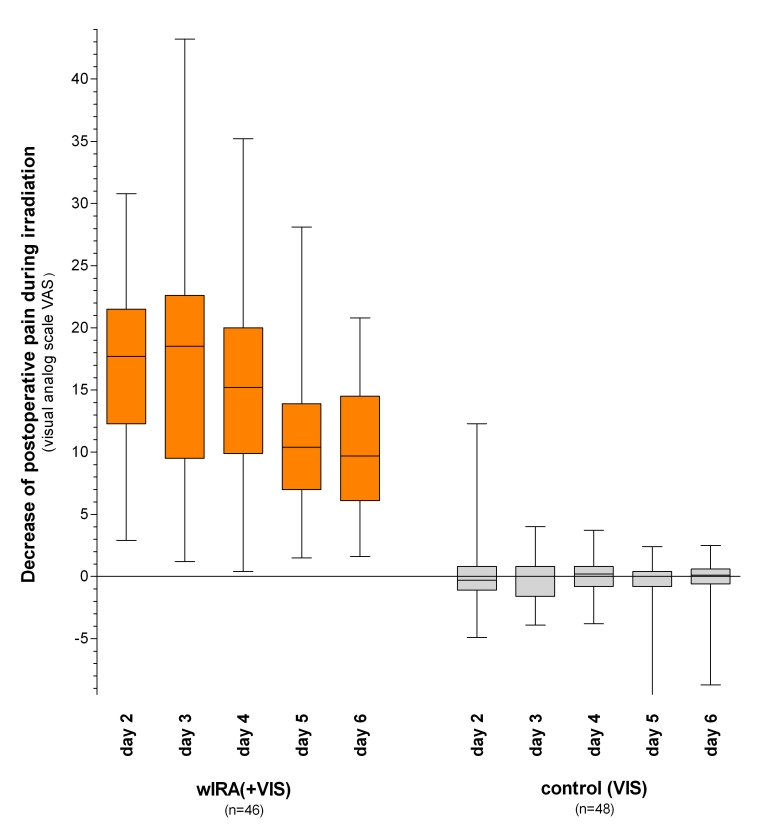

Independently from this a well documented case of a 64 year old female patient who had relapsing wound seromas and wound hematomas (without infection) after a hip operation (replacement of the acetabulum part of a 15 years old endoprosthesis) is remarkable: even after an additional operation with the only intention to stop the wound seromas and after approximately 8 aspirations of seroma fluid (up to approximately 90 mL within one aspiration) within 2 months, the wound seromas kept on recurring and a third operation was seriously considered. At that situation wIRA(+VIS) irradiation was started, beginning with 30 minutes twice a day and increasing up to 3 times one hour per day. Within a few days the seroma did no longer increase as usual, after approximately one week a slight decrease of seroma size was noticed clinically, and after approximately 2 months the seroma had resolved completely (both clinically and sonographically) without any aspiration of seroma fluid or operation since starting with wIRA(+VIS) irradiation, see Figure 8 (Fig. 8). The situation continued to keep stable further on (up to now approximately 1 year follow-up) with full mobility and being able to do sports. This experience is in accordance with the well known effect, that wIRA decreases hypersecretion and inflammation.

Figure 8. Example of a successful treatment of recurrent wound seromas with wIRA .

A 64 year old female patient had relapsing wound seromas and wound hematomas (without infection) after a hip operation (replacement of the acetabulum part of a 15 years old endoprosthesis) even after an additional operation with the only intention to stop the wound seromas and after approximately 8 aspirations of seroma fluid (up to approximately 90 mL within one aspiration) within 2 months, and a third operation was seriously considered: Figure A shows the sonographic state. At that situation wIRA(+VIS) irradiation was started, beginning with 30 minutes twice a day and increasing up to 3 times one hour per day. Within a few days the seroma did no longer increase as usual, after approximately one week a slight decrease of seroma size was noticed clinically (Figure B), Figure C shows reduced seroma size after 18 days, Figure D after 29 days and after approximately 2 months the seroma had resolved completely (both clinically and sonographically) without any aspiration of seroma fluid or operation since starting with wIRA(+VIS) irradiation (sonographic pictures published with kind approval of Dr. Michael Paulus, Herzogenaurach, Germany).

wIRA for persistent postoperative pain

wIRA can be used successfully for persistent postoperative pain:

After a thoracotomy with a successful coronary bypass operation sternal pains persisted for 9 months in a female patient, especially all movements, which expanded the thorax (like bringing the arms to the side backwards), caused an increase of pain – the two parts of the sternum showed a dehiscence on magnetic resonance tomography of 7 mm in spite of the cerclages –, three times 300 mg tramadol per day and in addition several times 25 mg tramadol per day (in total approximately 350-400 mg tramadol per day) (and for a period of time in combination with amitryptilin in analgesic indication) were necessary. Within 6 weeks of irradiating with wIRA(+VIS) 30-45 minutes per day led to a marked reduction of pain and only 100 mg tramadol per day were sufficient. During each irradiation the subjective state improved from 30 to 80-90 on a VAS (0-100, 0 representing extremely bad, 100 extremely good). After a few additional weeks pain was further decreased and analgesic medication could be stopped completely.

Perspectives for wIRA for the improvement of healing of acute wounds

As positive effects both of preoperative [3] and of postoperative [4], [5] warming have already been shown, it seems clinically prudent to use wIRA both pre- and postoperatively, e.g. in abdominal and thoracic operations.

wIRA can be used preoperatively (e.g. during 1-2 weeks) to precondition donor and recipient sites of skin flaps, transplants or partial-thickness skin grafts, and postoperatively to improve wound healing and to decrease pain, inflammation and infections at all mentioned sites.

wIRA can be used to support routine pre- or intraoperative antibiotic administration or it might even be discussed to replace this under certain conditions by wIRA [5].

Aspects to use wIRA in combination with a photodynamic therapy PDT to prevent or decrease wound infections are presented in [54].

References

- 1.Hoffmann G. Principles and working mechanisms of water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) in relation to wound healing [review] GMS Krankenhaushyg Interdiszip. 2007;2(2):Doc54. Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/journals/dgkh/2007-2/dgkh000087.shtml. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann G. Wassergefiltertes Infrarot A (wIRA) zur Verbesserung der Wundheilung [Übersichtsarbeit] [Water-filtered infrared A (wIRA) for the improvement of wound healing [review]]. GMS Krankenhaushyg Interdiszip. 2006;1(1):Doc20. (Ger). Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/journals/dgkh/2006-1/dgkh000020.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melling AC, Ali B, Scott EM, Leaper DJ. Effects of preoperative warming on the incidence of wound infection after clean surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:876–880. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plattner O, Akca O, Herbst F, Arkilic CF, Függer R, Barlan M, Kurz A, Hopf H, Werba A, Sessler DI. The influence of 2 surgical bandage systems on wound tissue oxygen tension. Arch Surg. 2000;135:818–822. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.7.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartel M, Hoffmann G, Wente MN, Martignoni ME, Büchler MW, Friess H. Randomized clinical trial of the influence of local water-filtered infrared A irradiation on wound healing after abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 2006;93(8):952–960. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5429. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer JB, Nielsen SP, Hoffmann G. Improvement of wound healing by water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) in patients with chronic venous leg ulcers including evaluation using infrared thermography. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2008;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kivisaari J, Vihersaari T, Renvall S, Niinikoski J. Energy metabolism of experimental wounds at various oxygen environments. Ann Surg. 1975;181:823–828. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197506000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kühne HH, Ullmann U, Kühne FW. New aspects on the pathophysiology of wound infection and wound healing - the problem of lowered oxygen pressure in the tissue. Infection. 1985;13:52–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01660413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niinikoski J, Gottrup F, Hunt TK. The role of oxygen in wound repair. In: Janssen H, Rooman R, Robertson JIS, editors. Wound healing. Petersfield: Wrightson Biomedical Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann G. Improvement of wound healing in chronic ulcers by hyperbaric oxygenation and by waterfiltered ultrared A induced localized hyperthermia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1994;345:181–188. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2468-7_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buslau M, Hoffmann G. Hyperbaric oxygenation in the treatment of skin diseases [review] In: Fuchs J, Packer L, editors. Oxidative stress in dermatology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993. pp. 457–485. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buslau M, Hoffmann G. Die hyperbare Oxygenation (HBO) - eine adjuvante Therapie akuter und chronischer Wundheilungsstörungen. [Hyperbaric oxygenation - an adjuvant therapy of acute and chronic wound healing impairments]. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1993;179:39–54. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann G, Buslau M. Treatment of skin diseases by hyperbaric oxygenation. In: Cramer FS, editor. Proceedings of the Eleventh International Congress on Hyperbaric Medicine. Flaggstaff, USA: Best Publishing Company; 1995. pp. 20–21.pp. 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for wound healing. World Wide Wounds. 2001. Available from: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2001/april/Wright/HyperbaricOxygen.html.

- 15.Knighton DR, Silver IA, Hunt TK. Regulation of wound-healing angiogenesis - effect of oxygen gradients and inspired oxygen concentration. Surgery. 1981;90:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnikol WKR, Teslenko A, Pötzschke H. Eine neue topische Behandlung chronischer Wunden mit Haemoglobin und Sauerstoff: Verfahren und erste Ergebnisse. [A new topic treatment of chronic wounds with haemoglobin and oxygen: procedere and first results]. Z Wundheilung - J Wound Healing. 2005;10(3):98–108. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jünger M, Hahn M, Klyscz T, Steins A. Role of microangiopathy in the development of venous leg ulcers. Vol. 23. Basel: Karger; 1999. pp. 180–193. (Progr. Appl. Microc.). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaupel P, Stofft E. Wassergefilterte Infrarot-A-Strahlung im Vergleich zu konventioneller Infrarotstrahlung oder Fango-Paraffin-Packungen: Temperaturprofile bei lokaler Wärmetherapie. In: Vaupel P, Krüger W, editors. Wärmetherapie mit wassergefilterter Infrarot-A-Strahlung. 2. Aufl. [Thermal therapy with water-filtered infrared-A radiation]. Stuttgart: Hippokrates; 1995. pp. 135–147. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaupel P, Rzeznik J, Stofft E. Wassergefilterte Infrarot-A-Strahlung versus konventionelle Infrarotstrahlung: Temperaturprofile bei lokoregionaler Wärmetherapie. [Water-filtered infrared-A radiation versus conventional infrared-A radiation: temperature profiles in local thermal therapy]. Phys Med Rehabilitationsmed Kurortmed. 1995;5:77–81. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stofft E, Vaupel P. Wassergefilterte Infrarot-A-Strahlung versus Fango-Paraffin-Packung: Temperaturprofile bei lokoregionaler Wärmetherapie. [Water-filtered infrared-A radiation versus fango paraffine packages: temperature profiles in local thermal therapy]. Phys Med Rehabilitationsmed Kurortmed. 1996;6:7–11. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercer JB, de Weerd L. The effect of water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) irradiation on skin temperature and skin blood flow as evaluated by infrared thermography and scanning laser Doppler imaging. Thermology Int. 2005;15(3):89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pascoe DD, Mercer JB, de Weerd L. Biomedical Engineering Handbook. 3rd edition. Boca Raton (Florida/USA): Taylor and Francis Group, CRC press; 2006. Physiology of thermal signals; pp. 21-1–21-20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hellige G, Becker G, Hahn G. Temperaturverteilung und Eindringtiefe wassergefilterter Infrarot-A-Strahlung. In: Vaupel P, Krüger W, editors. Wärmetherapie mit wassergefilterter Infrarot-A-Strahlung. 2. Aufl. [Thermal therapy with water-filtered infrared-A radiation]. Stuttgart: Hippokrates; 1995. pp. 63–79. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumann H, Schempp CM. wIRA in der Wundtherapie - Erste Erfahrungen in der Anwendung bei chronischen Wunden in der Universitäts-Hautklinik Freiburg [wIRA in wound therapy - first experiences in the application in chronic wounds in the Department of Dermatology of the University Hospital Freiburg] 2004.

- 25.Heinemann C, Elsner P. Personal communication. 2002.

- 26.Fuchs SM, Fluhr JW, Bankova L, Tittelbach J, Hoffmann G, Elsner P. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) and waterfiltered infrared A (wIRA) in patients with recalcitrant common hand and foot warts. Ger Med Sci. 2004;2:Doc08. Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/gms/2004-2/000018.shtml. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Möckel F, Hoffmann G, Obermüller R, Drobnik W, Schmitz G. Influence of water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) on reduction of local fat and body weight by physical exercise. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2006;4:Doc05. Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/gms/2006-4/000034.shtml. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biland L, Barras J. Die wassergefilterte Infrarot-A-Hyperthermie zur Behandlung venöser Ulcera. [Water-filtered infrared-A induced hyperthermia used as therapy of venous ulcers]. Hefte Wundbehand. 2001;5:41. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffmann G. Water-filtered infrared A (wIRA) for the improvement of wound healing in acute and chronic wounds. Wassergefiltertes Infrarot A (wIRA) zur Verbesserung der Wundheilung bei akuten und chronischen Wunden. Z Wundheilung - J Wound Healing. 2005;(special issue 2):130. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffmann G. Wassergefiltertes Infrarot A (wIRA) zur Verbesserung der Wundheilung bei akuten und chronischen Wunden. [Water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) for the improvement of wound healing of acute and chronic wounds]. MedReport. 2005;29(34):4. (Ger). Available from: http://www.medreports.de/medpdf05/mreport34_05.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Felbert V, Streit M, Weis J, Braathen LR. Anwendungsbeobachtungen mit wassergefilterter Infrarot-A-Strahlung in der Dermatologie. [Application observations with water-filtered infrared-A radiation in dermatology]. Dermatol Helvetica. 2004;16(7):32–33. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Illing P, Gresing T. Improvement of wound healing in severely burned children by water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) GMS Ger Med Sci. 2008;6 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haupenthal H. In vitro- und in vivo-Untersuchungen zur temperaturgesteuerten Arzneistoff-Liberation und Permeation [Thesis] [In vitro and in vivo investigations of temperature dependent drug liberation and permeation]. Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg-Universität; 1997. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankova L, Heinemann C, Fluhr JW, Hoffmann G, Elsner P. Improvement of penetration of a topical corticoid by waterfiltered infrared A (wIRA). 1st Joint Meeting 14th International Congress for Bioengineering and the Skin & 8th Congress of the International Society for Skin Imaging; 2003 May 21-24; Hamburg. 2003. p. P96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otberg N, Grone D, Meyer L, Schanzer S, Hoffmann G, Ackermann H, Sterry W, Lademann J. Water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) can act as a penetration enhancer for topically applied substances. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2008;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meffert H, Buchholtz I, Brenke A. Milde Infrarot-A-Hyperthermie zur Behandlung der systemischen Sklerodermie. [Mild infrared-A hyperthermia for treatment of systemic scleroderma]. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1990;176(11):683–686. (Ger). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foss P. Einsatz eines patentierten, wassergefilterten Infrarot-A-Strahlers (Hydrosun) zur photodynamischen Therapie aktinischer Dyskeratosen der Gesichts- und Kopfhaut. [Application of a patented water-filtered infrared-A radiator (Hydrosun) for photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis of the skin of the face and the scalp]. Z naturheilkundl Onkologie krit Komplementärmed. 2003;6(11):26–28. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hübner K. Die Photo-dynamische Therapie (PDT) der aktinischen Keratosen, Basalzellkarzinome und Plantarwarzen. [The photodynamic therapy (PDT) of the actinic keratoses, basal cell carcinomas and plantar warts]. derm - Praktische Dermatologie. 2005;11(4):301–304. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickreiter B. Phototherapie - Therapeutische Möglichkeiten von Infrarotstrahlung und sichtbarem Licht. [Phototherapy - therapeutic possibilities of infrared radiation and visible light]. Gesundes Leben. 2002;79(6):52–57. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meffert H, Müller GM, Scherf HP. Milde Infrarot-A-Hyperthermie zur Behandlung von Erkrankungen des rheumatischen Formenkreises. Anhaltende Verminderung der Aktivität polymorphkerniger Granulozyten. [Mild infrared-A-hyperthermia for the treatment of diseases of the rheumatic disorders circle. Persistent decrease of the activity of granulocytes with polymorph nuclei]. Intern Sauna-Arch. 1993;10:125–129. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Falkenbach A, Dorigoni H, Werny F, Gütl S. Wassergefilterte Infrarot-A-Bestrahlung bei Morbus Bechterew und degenerativen Wirbelsäulenveränderungen: Effekte auf Beweglichkeit und Druckschmerzhaftigkeit. [Water-filtered infrared-A irradiation in Morbus Bechterew and degenerative vertebral column diseases: effects on flexibility and feeling of pressure]. Österr Z Physikal Med Rehab. 1996;6(3):96–102. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffmann G. Improvement of regeneration by local hyperthermia induced by waterfiltered infrared A (wIRA) Int J Sports Med. 2002;23(Suppl 2):S145. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer D, Schröder M, Harms K. Vorteile der wassergefilterten gegenüber herkömmlicher Infrarot-Strahlung in der Neonatologie. [Advantages of water filtered over conventional infrared irradiation in neonatology]. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2000;204(3):85–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-10202. (Ger). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe E, Vinogradova I, Meffert H. Neue Methoden gegen Warzen: wIRA - effektiv und wirtschaftlich interessant. [New methods against warts: wIRA - effective and commercially interesting]. Dtsch Dermatologe. 2004;52(7):487–489. (Ger). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Applegate LA, Scaletta C, Panizzon R, Frenk E, Hohlfeld P, Schwarzkopf S. Induction of the putative protective protein ferritin by infrared radiation: implications in skin repair. Int J Mol Med. 2000;5(3):247–251. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.5.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burri N, Gebbers N, Applegate LA. Chronic infrared-A radiation repair: Implications in cellular senescence and extracellular matrix. In: Pandalai SG, editor. Recent Research Developments in Photochemistry & Photobiology. Vol. 7. Trivandrum: Transworld Research Network; 2004. pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gebbers N, Hirt-Burri N, Scaletta C, Hoffmann G, Applegate LA. Water-filtered infrared-A radiation (wIRA) is not implicated in cellular degeneration of human skin. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2007;5:Doc08. Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/gms/2007-5/000044.shtml. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menezes S, Coulomb B, Lebreton C, Dubertret L. Non-coherent near infrared radiation protects normal human dermal fibroblasts from solar ultraviolet toxicity. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111(4):629–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frank S, Menezes S, Lebreton-De Coster C, Oster M, Dubertret L, Coulomb B. Infrared radiation induces the p53 signaling pathway: role in infrared prevention of ultraviolet B toxicity. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15(2):130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2005.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danno K, Horio T, Imamura S. Infrared radiation suppresses ultraviolet B-induced sunburn-cell formation. Arch Dermatol Res. 1992;284(2):92–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00373376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Enoch P, Price P. Should alternative endpoints be considered to evaluate outcomes in chronic recalcitrant wounds? World Wide Wounds. 2004. Available from: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2004/october/Enoch-Part2/Alternative-Enpoints-To-Healing.html.

- 52.Hoffmann G, Siegfried I. Volkskrankheit Rückenschmerz: neue Sichtweisen. Seminar des Arbeitskreises Sportmedizin der Akademie für ärztliche Fortbildung und Weiterbildung der Landesärztekammer Hessen. Bad Nauheim, 05.06.2004. [Common illness backache: new ways of looking at]. Düsseldorf, Köln: German Medical Science; 2005. p. Doc 04ruecken1. (Ger). Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/meetings/ruecken2004/04ruecken1.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pediani R. What has pain relief to do with acute surgical wound healing? World Wide Wounds. 2001. Available from: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2001/march/Pediani/Pain-relief-surgical-wounds.html.

- 54.von Felbert V, Schumann H, Mercer JB, Strasser W, Daeschlein G, Hoffmann G. Therapy of chronic wounds with water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) GMS Krankenhaushyg Interdiszip. 2007;2(2):Doc25. Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/journals/dgkh/2008-2/dgkh000085.shtml. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karu TI, Pyatibrat LV, Kalendo GS. Cell attachment to extracellular matrices is modulated by pulsed radiation at 820 nm and chemicals that modify the activity of enzymes in the plasma membrane. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;29(3):274–281. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akca O, Melischek M, Scheck T, Hellwagner K, Arkilic CF, Kurz A, et al. Postoperative pain and subcutaneous oxygen tension. Lancet. 1999;354:41–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hopf HW, Hunt TK, West JM, Blomquist P, Goodson WH, III, Jensen JA, et al. Wound tissue oxygen tension predicts the risk of wound infection in surgical patients. Arch Surg. 1997;132:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430330063010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheikh AY, Gibson JJ, Rollins MD, Hopf HW, Hussain Z, Hunt TK. Effect of hyperoxia on vascular endothelial growth factor levels in a wound model. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1293–1297. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.11.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knighton DR, Fiegel VD, Halverson T, Schneider S, Brown T, Wells CL. Oxygen as an antibiotic. The effect of inspired oxygen on bacterial clearance. Arch Surg. 1990;125:97–100. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1990.01410130103015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mader JT, Brown GL, Guckian JC, Wells CH, Reinarz JA. A mechanism for the amelioration by hyperbaric oxygen of experimental staphylococcal osteomyelitis in rabbits. J Infect Dis. 1980;142:915–922. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alborova A, Lademann J, Meyer L, Kramer A, Teichmann A, Sterry W, Antoniou C. Einsatz der Laser-Scan-Mikroskopie zur Charakterisierung der Wundheilung. [Application of laser scanning microscopy for the characterization of wound healing]. GMS Krankenhaushyg Interdiszip. 2007;2(2):Doc37. (Ger). Available from: http://www.egms.de/en/journals/dgkh/2007-2/dgkh000070.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sattler H, Stellmann A. Experiences with water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) in patients during rehabilitation after hip and knee endoprosthesis operations in Bad Dürkheim, Germany. 2002-2004.