Abstract

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) has been posited as a promising methodology to address health concerns at the community level, including cancer disparities. However, the major criticism to this approach is the lack of scientific grounded evaluation methods to assess development and implementation of this type of research. This paper describes the process of development and implementation of a participatory evaluation framework within a CBPR program to reduce breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer disparities between African Americans and whites in Alabama and Mississippi as well as lessons learned. The participatory process involved community partners and academicians in a fluid process to identify common ground activities and outcomes. The logic model, a lay friendly approach, was used as the template and clearly outlined the steps to be taken in the evaluation process without sacrificing the rigorousness of the evaluation process. We have learned three major lessons in this process: (1) the importance of constant and open dialogue among partners; (2) flexibility to make changes in the evaluation plan and implementation; and (3) importance of evaluators playing the role of facilitators between the community and academicians. Despite the challenges, we offer a viable approach to evaluation of CBPR programs focusing on cancer disparities.

Keywords: Participatory evaluation, cancer disparities, community-based participatory research, logic model

1. Introduction

While great progress has been made in research on the elimination of health disparities in the past few years, further work is necessary in translating research to practice. Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) is a promising methodology that not only fosters research and capacity building, but also promotes ownership and sustainability by mobilizing underserved communities as political and social actors in the elimination of cancer disparities. CBPR is “a partnership approach to research that equitably involves, for example, community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all aspects of the research process.” (Israel et al). The World Health Organization defines health promotion as the “process of enabling people and communities to take control over their health and its determinants” (WHO, 1984). Thus, by definition health should be promoted through community involvement in which community members decide what, when, where, and how health will be promoted and disease will be prevented in their communities.

Although the concept of community empowerment and community partnership have been successfully used in education and public health in the past 30 years, most of these programs have been implemented in developing countries. More recently, public health professionals have more broadly embraced this concept in the United States and the results have been very encouraging (Adams ML, 2007; Christopher et. al., 2007; English et. al., 2006; Hughes Halbert et. al., 2006; Hutson et. al., 2007; Mishra et. al., 2007; Smith et. al., 2008; Tanjasiri et. al., 2007). Under this approach, community partners, along with academic partners, share responsibilities and priorities and solutions are implemented in partnership rather than placing academicians or health care professionals in decision-making roles for the community. However, like any paradigm shift, this is an arduous process in which academicians and community members need to “retool” themselves, negotiate resources, and, above all, be truly committed to reducing health disparities.

For a variety of reasons, even more challenging is the evaluation of community-based participatory programs. First, community-based organizations and community members may not see the need for evaluation or may perceive “evaluation” as scrutiny and policing from funders. Second, they may not understand the “academic” evaluation process. Third, academic institutions, community-based organizations, and community-at-large may have different definitions of “desirable outcomes” and/or they may use different “tools” to measure “success” (Nichols, 2002). Fourth, disenfranchised communities may have negative perceptions (and sometimes negative experiences) completing surveys or forms for fear that the obtained data will be used against them. Fifth, most evaluations are developed from the top down based on the biomedical model rather than participatory research or empowerment models. As pointed out by Crishna (2006), most of the traditional evaluation methods do not capture the “spirit of change” in people. Or, we may even question the obtained results of traditional evaluations given the reluctance and mistrust in some underserved communities. As such, CBPR also involves development and implementation of a participatory evaluation process in which stakeholders and participants are part of the process.

Crishna (2006) proposes four main principles when conducting participatory evaluation: “(1) Everyone involved in the program shares control over the evaluation process; (2) The objectives are set jointly, in a group, with all the people concerned in the program, keeping in mind that everyone has his or her own agenda; (3) Working out the difficulties faced by everyone helps in strengthening the program; and (4) There is a process of collective awareness raising.” Based on these principles and the limitations mentioned above, it is critical that evaluators and community partners jointly design the evaluation process and define short- and long-term “success”. This paper describes the process of development and implementation of a participatory evaluation framework within a CBPR program to reduce breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer disparities between African Americans and whites in Alabama and Mississippi as well as lessons learned.

2. Context

The initial establishment of the Deep South Network for Cancer Control (DSN) and its activities is described elsewhere (Author et al., 2005). The focus of this paper is the development and implementation of a participatory evaluation during the second funding phase of the program (DSN-II). The overall goal of the DSN-II was to build on the already established community and institutional capacity in order to eliminate breast, cervical and colorectal cancer disparities between African Americans and whites in Alabama and Mississippi by jointly developing a Community Action Plan with the targeted communities. This goal was set to be accomplished in two phases. The first phase consisted of expansion of the Network, capacity building among all partners, and needs/assets assessment. The second phase consisted of development and implementation of the Community Action Plan.

The development and implementation of the DSN-II is guided by the principles of Community-Based Participatory Research (Israel et al., 2003). Within this program, “community” is defined as our target population (African Americans in the targeted counties in Alabama and Mississippi) which were represented by community partners in the DSN; i.e., community health advisors, community-based organizations, community leaders and agents of change such as ministers, teachers, politicians, etc. Since not all community members were able to participate in every activity, partners were encouraged throughout the process to share the DSN initiatives and challenges with their constituents (Israel et al, 2003). In addition, a Steering Committee was formed with representation from community partners, staff, and investigators.

We also follow the Empowerment Model as proposed by Paulo Freire through his work in Brazil that “influenced the transformation of the research relationship from viewing communities as objects of study to viewing community members as subjects of their own experience and inquiry” (Wallerstein & Divan, 2003). The Empowerment Theory, as proposed by Paulo Freire, provides a map for selecting, recruiting, and maintaining a broad-based network partnership as well as development and implementation of the Community Action Plan. The Community Empowerment approach holds that before community members will address particular social change goals introduced from the outside, they must first be organized and empowered to address their own concerns and goals (Freire, 1970). It begins with a true dialogue in which everyone participates equally to identify common problems and solutions. Once the individual strengths and the shared responsibilities are identified, the network begins to work together toward a common goal.

3. Development of the Evaluation Logic Model

The logic model was chosen as the evaluation framework for this program because it clearly outlines the steps to be taken in the evaluation process using terminology and an approach that is easily understandable by lay individuals without sacrificing the rigorousness of the evaluation process (Millar et al., 2001; Kaplan & Garrett, 2005; Dykeman et al., 2003; Conrad et al., 1999; Fielden et al., 2007). Conrad and colleagues (1999) defines the logic model as “… a graphic representation of a program that describes the program's essential components and expected accomplishments and conveys the logical relationship between these components and their outcomes”.

The development and implementation of the evaluation logic model were consistent with the theoretical framework described above. That is, all components of the evaluation were developed and implemented by an integrated effort of staff, community partners, and investigators. The process was very fluid and the approach to each task related to evaluation was dependent on the nature of the task. For instance, data collection approaches and methods were discussed first in a group, whereas assessment tools were mostly developed by the investigators and partners provided feedback.

The multi-component nature of the DSN-II required a triangulated mixed-method evaluation plan focusing on process, impact and outcomes using both quantitative and qualitative assessments which were implemented throughout the project. Process evaluations included the activities that occurred during the planning, development, and implementation of the project. Process evaluations provided the network steering committee with information that could be used to track the progress of the project. This information not only allowed errant strategies to be detected, it also allowed alternative strategies to be developed and implemented. Impact evaluations focused on the immediate effects of program activities. When impact evaluations revealed that program/intervention effects were inconsistent with project goals and objectives, network steering committee members were alerted to the need to either change the existing intervention strategies, or create different strategies altogether. Outcome evaluations focused on assessment of the extent to which program objectives and goals were reached.

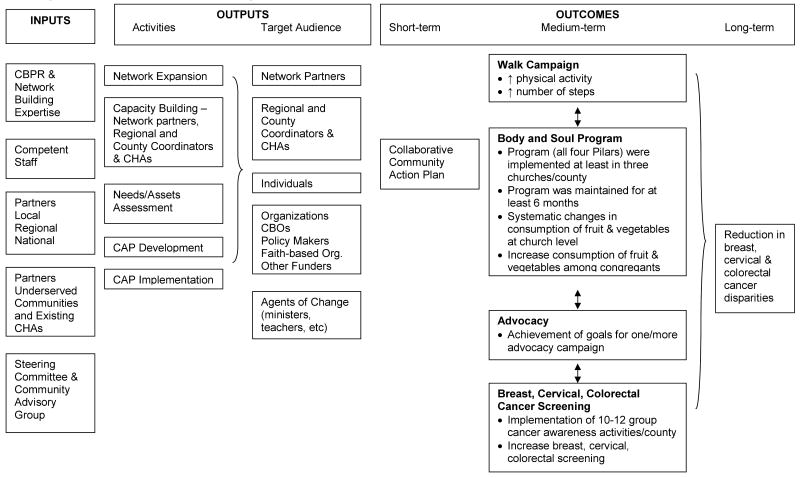

The Logic Model guided the process, impact, and outcomes evaluation. This model links program inputs and activities to program outcomes and ultimately to the main goals of the project – to reduce breast, cervical and colorectal cancer disparities between African Americans and whites in targeted counties in Alabama and Mississippi. Program inputs included resources that went into the proposed program; outputs included activities (actual events or actions that took place) and the target audience; outcomes were the impact of the proposed program. For the DSN-II, those steps of the logic model translated into the following chain of activities: 1) network expansion; 2) capacity building; 3) needs/assets assessment; 4) development and implementation of a community action plan that would lead to; 5) increased physical activity, healthy eating habits, advocacy, cancer screening, and ultimately; 6) the reduction/elimination of breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer health disparities between African Americans and whites in targeted counties in Mississippi and Alabama (see Figure1).

Figure 1. Evaluation Framework - Logic Model.

3.1. Process Evaluation

Process evaluation began in the initial months of Phase I in the form of documentation of inputs and planning strategies, and it continued throughout the project as described below. A major component of the process evaluation was to assess fidelity of the proposed program and collaborative participation of network partners to determine whether this methodology was effective in developing a culturally relevant approach to mobilize a community to reduce/eliminate health disparities in breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer between African Americans and whites in targeted counties in Alabama and Mississippi.

Network Expansion/Maintenance

The network expansion began with recruitment of community partners. It was critical that representatives of all segments of the community (e.g., health, education, political leadership) were represented. As such, county and regional coordinators, with the assistance of already engaged volunteers from DSN Phase I, were asked to generate a list of potential partners as well as potential Community Health Advisors (“natural helpers” who were already engaged in helping others in the community). Once they agreed to participate in the network, each partner completed a baseline questionnaire on their expectations as well as their expertise (what they will bring to the program), and these issues were revisited throughout the program to assure that the network was meeting the partners' expectations. In order to assure equal representation in the decision-making process, a network steering committee was established with representation of investigators, staff, Community Network Partners, and Community Health Advisors. This committee met monthly to discuss the day-to-day operations of the program, including feedback on the evaluation process.

Capacity Building

Capacity building refers to the readiness or ability of a network and its partners to take action aimed at changing risk/protective behaviors, and transforming community conditions and systems so that a supportive context exists to sustain behavior change over time. Document analysis played a major role in monitoring capacity building activities within the project. Specific types of documents included: minutes of network steering committee and network meetings, memoranda of understanding between network partners and academic team, signed informed consent forms of Community Health Advisors, training manuals, attendance rosters, and graduation ceremony agenda and list of graduates. Depending on the training, participants completed pre- and post-test assessments at each training session to assess changes in knowledge and confidence to implement the knowledge and skills learned in the sessions. Satisfaction questionnaires regarding the training were also administered.

Needs/Assets Assessment

The primary goals of this activity were to truly listen to representatives at different levels in the community, perform an extensive review of the literature, conduct an inventory of cancer prevention/early detection programs in the targeted counties, and review accomplishments made by DSN thus far. As such, the process evaluation activities focused on whether this activity followed the guidelines of CBPR as well as proposed methodology. Examples of assessment tools included: (a) initial discussions: analysis of transcripts, assurance that community partners were represented in these groups and given the opportunity to openly discuss their concerns and suggestions; (b) working groups: review whether the working groups followed the literature review guidelines and community program/research inventory, provide assurance that community partners were represented in these groups, reviewed minutes of working group meetings and observed feedback meetings with community members.

Community Action Plan Development

The first step in the process evaluation was to assure that the development of Community Action Plan followed the CBPR principles and the proposed methodology. Examples of assessment tools included: review of network steering committee meetings, review of minutes of meetings in the targeted counties, documentation of active involvement of community partners in the CAP development.

Community Action Plan Implementation

Community Action Plan implementation was evaluated on whether the activities were being implemented according to the proposed plan, whether community partners were actively engaged and took ownership, and whether the agreed upon outcomes were being achieved.

3.2. Impact and Outcome Evaluation

As described above, impact evaluation focuses on the immediate effects of program activities. The impact evaluation component of this program refers to the short-term outcome outlined in the Logic Model: Production of collaborative community action plan. Overall, the evaluation was designed to (a) document development and implementation of the Community Action Plan; (b) assess the network involvement in the Community Action Plan (is it a collaborative process?); and (c) assess the delivery and receipt of the proposed Community Action Plan. Outcome evaluation refers to medium- and long-term outcomes listed in the Logic Model. These outcomes were defined by the community during the development of the Community Action Plan.

4. Implementation of the Evaluation

An initial evaluation plan and logic model was developed by the investigators in consultation with some community partners for the grant submission. As previously discussed we chose the logic model based on its simplicity. It can be easily understood by lay individuals without sacrificing the rigorousness of the evaluation process. Once the program was funded, the plan was revisited and an evaluation team of investigators and senior staff were established who would work under the guidance of the network steering committee. As such, the initial plan was developed and implemented by the academic partner, and as the community partners joined the network the evaluation was revisited and revised as described below. It follows a detailed evaluation plan worksheet that is agreed upon among the investigators, staff, and partners based on the pre-established goals for each phase and component. This worksheet details the goals, the evaluation question(s), data collection tool(s), when measurements were to be administered, and the person responsible for each objective, and it reflects a detailed “to do list” based on the logic model. A sample of the worksheet is presented on Table 1. As stated earlier, the primary focus of this paper is to discuss the process and implementation of a participatory evaluation plan as a viable approach in the evaluation of community-based participatory programs focusing on the reduction and/or elimination of cancer disparities in the United States. As such, we will not focus on the results, but rather on how the evaluation was implemented and data was collected.

Table 1. Evaluation Worksheet: WALK Campaign.

| Process Evaluation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Evaluation Questions | Data Collection Tools | When Administered | Responsible |

| All Staff will be trained to train CNP/CHA members how to implement a WALK campaign | Were Staff trained to train CNP/CHA members how to implement a WALK campaign? What was staff's feedback about the training? What were the changes in knowledge between pre- and post-training? |

Attendance roster from training sessions Post-test Pre- and post-test |

Staff Training, 02/07 | Program Director Data Manager Data Manager |

| DSN Staff will train CNP/CHA members how to implement a WALK Campaign and act as Team Leaders | How many CNP/CHA members were trained on how to implement a WALK campaign? What was the feedback about the training? What were the changes in knowledge between pre- and post-training? |

Attendance roster from County CNP meetings Post-test Pre- and post-test |

CNP/CHA Training session | County Coord. |

| 30% of CNP/CHA members will act as WALK Team Leaders | What percentage of CNP/CHA members agreed to act as WALK Team Leaders? What percentage was retained at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months? |

Commitment form Reports from Team Leaders |

CNP/CHA Training Session Follow-up at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months |

County Coord. |

| Each Team Leader will recruit 2-9 team members | Did each Team Leader recruit 2-9 team members? | WALK Team rosters | Report from CNP/CHA member to County Coordinator | Team Leaders and County Coordinators |

| Each WALK Team member will receive a packet of materials | Did each WALK team member receive a packet? | Distribution lists | Orientation meeting Packet distribution list | Team Leaders and County Coordinators |

| Maintain WALK teams in each county | What percentage of WALK Team members continued to participate? | WALK Team rosters | Follow-up time (6, 12, 18, 24 months) | Team Leaders & County Coord |

| Outcome Evaluation | ||||

| Increase physical activity | Did levels of physical activity increase among participants in the WALK Campaign? | Baseline and 12 & 24 month f/u surveys | Orientation meeting with members and at 12 and 24 months | County Coordinators |

| Did steps walked increase among WALK team members? | Step forms | Continuous | Team Leader County Coord. | |

Since this was the second phase of DSN, we had already established strong partnerships in the community and had the staff in place to begin this project. As such, identification of “inputs” was very clear and did not generate a great deal of discussion among partners once the logic model was presented. Although partners understood the logical steps outlined in the logic model, it seems that the outlined activities and target audience were not of concern, but HOW these activities were conducted was very important to partners at all levels. Also, it was evident that partners were concerned about their role and their contribution to the process in terms of “doing it right” or “Am I the best person to do this?” Most of the changes and discussion with regard to the logic model were centered in the outcomes and how they would be measured (“what is success?”).

Internal Organization Structure

The first step before we expanded the network was the internal organization of the program within the academic site. Given the complex nature of the project as well as the fact that we had staff in multiple counties across the states of Alabama and Mississippi, a centralized repository for storing and sharing project documents (including minutes of local and regional meetings) was necessary for internal communication among investigators, staff, and network steering committee. After exploring a number of possibilities, the network steering committee opted for having a WebCT website as centralized repository of documents, as a locus for discussing the development and revision of draft documents and forms, and as a central calendar to record project events and activities. Given the dispersed data collection and multi-site nature of the project, a flow-chart showing the path that data would take from initial collection through cleaning and analysis to final storage was developed. Minutes of all conference calls, meetings with community members, etc were kept up to date on WebCT website and were available to staff, investigators, and the network steering committee. We also established online mechanisms using state-of-the-art secure software to collect information from the various study locations.

Investigators and staff underwent an extensive training program that included modules on Community-Based Participatory Research, recruiting and motivating volunteers, and meeting planning/organization among other relevant topics. The training continued until investigators and staff felt comfortable with the Community-Based Participatory Research methodology and felt confident that they could implement its principles in the targeted counties. When establishing trust in underserved communities it is critical that investigators and staff have the skills to engage community members. As pointed out by Paulo Freire, based on the fact that the university received the funding, investigators and staff represent the “oppressor” they must be well-trained in the skills of equalizing power to achieve equitable partnership with community members. Pre- and post-presentation knowledge of the topics covered as well as confidence in implementing CBPR in the community were assessed. Staff were also administered an anonymous satisfaction assessment about the training.

Expansion of the Network/Capacity Building

Once staff and investigators were trained, we began expansion of the network. County and regional coordinators contacted potential network partners and meetings were held to explain the project and gauge interest in participating. Interested representatives of institutions and agents of change from the targeted communities signed a Memoranda of Understanding. These Community Network Partners signed consent forms and baseline data were collected including basic demographics as well as information on what unique skills, talents, experiences, and resources the Community Network Partners would bring to the project. Community Network Partnerships were established in each county with representation at the network steering committee. As mentioned above, county and regional coordinators were trained and empowered to facilitate these network meetings, and assist in the capacity building of community partners. Because the focus of this paper is on the development and implementation of a participatory evaluation the description of the specific strategies on how trust was established is beyond the scope of this paper. Simple strategies ranging from “undressing” of tiles and positions (i.e., everyone in the network is identified by his/her first name) to addressing other community concerns besides cancer (e.g., provision of speakers in other health topics to the local school) were implemented.

Since the Community Action Plan was going to be developed by the community, we did not know its focus, scope, goals, outcomes, etc. As such, Community Network Partners were recruited with the commitment of assisting the development of the Community Action Plan. Once the plan was developed, they would renew their commitment based on their interest and expertise to assist with implementation.

A second important group in the Network was the Community Health Advisors. The success in the first DSN was the training of Community Health Advisors to disseminate cancer screening information in their communities. In consultation with Community Health Advisors, they suggested a distinction to be made between Community Health Advisors and Community Network Partners. Although some Community Health Advisors attended the Community Network Partners meetings and some had a double role as Community Health Advisor and Community Network Partner, they perceived their role differently than Community Network Partner. In their perception, Community Network Partners were the agents of change that could influence the system, and the Community Health Advisors were the “soldiers” who would deliver the message to individuals. As such, Community Health Advisor groups were established in all targeted counties, and an extensive training program was undertaken which included modules on community based participatory research, overall cancer information, and specific information on the cancers of interest for this project (cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer), recruitment and retention strategies, research ethics, and community assets mapping. Existing Community Health Advisors from the first DSN were given the opportunity to continue and new Community Health Advisors were recruited and trained. Data collected from the Community Health Advisor during this training period included: consent forms, roles and expectations sheets, contact information, basic demographics, previous community activities, pre- and post- training knowledge, and an evaluation of the training program.

As implied above, the partnerships at the county level were being established, and partners were going through capacity building. They were trained on CBPR, and they identified which knowledge and skills were necessary for them to implement the outlined activities. As such, capacity building was an ongoing process via monthly meetings throughout the project since the necessary knowledge and skills changed as we progressed with the different activities. It should be noted that capacity building was done through partners training each other based on their expertise and experience. An outsider was brought in only when the expertise was not available within the group.

Needs/Assets Assessments

Although ideally, a mixed-method rigorous evaluation would be ideal, the community expressed that they did not want to complete any assessments and that their communities have been assessed multiple times by other academicians without any feedback. Community Network Partners and Community Health Advisors expressed that they knew what the needs and assets were and that we would get more valuable information by “talking to people” rather than administering measurements developed by the academic institution. As such, a compromise was made by applying scientific rigorousness, but also using the suggested methodology. Multiple drafts of the discussion group topic guide were developed based on feedback of partners and Community Health Advisors since it was critical that the same topic guide be used in all counties.

In assessing needs and assets, the process included as many partners as possible and at least three Community Health Advisors in each discussion group. A total of thirteen (13) discussion groups were conducted in Alabama, and eleven (11) in Mississippi. The selection process for each group included inviting partners and randomly selecting three Community Health Advisors in each participating county. The evaluation team found that this process was followed for the most part, but a small number of County Coordinators felt it was easier to select their most reliable Community Health Advisors to participate and two Mississippi groups had fewer than three Community Health Advisors as participants. Overall, this did not appear to be a major concern because the selected Community Health Advisors were demographically similar to the general group of Community Health Advisors.

The data was transcribed, and analyzed by two coders. A final summary was discussed with the network steering committee. As described below, the results led to a major change in the proposed logic model. Given the overall goal of the program (reduction in breast, cervical and colorectal disparities) and our previous experience in the community conducting screenings, we anticipated that communities were going to identify screening as a major focus of the Community Action Plan and that the working groups was going to be divided by cancer site.

The Alabama and Mississippi discussion groups recommended that the working groups be divided into three intervention levels (individual, provider and systems) rather than cancer site. The groups wanted to continue to focus on screenings and follow-ups for breast and cervical cancer, and colorectal cancer screening. The groups also wanted to focus on increasing awareness and activities that impacted risky lifestyles. The groups expressed concern about obesity, diabetes, smoking, poor nutrition and the lack of exercise in their communities. The groups had observed the impact of capacity building and networking in their communities, and they wanted to learn how to more effectively advocate for change.

Community Action Plan Development

Based on the results of the discussion groups, working groups were organized across counties with representation of Community Health Advisors, partners, staff, and investigators. An effort was made to have a member of the evaluation team and/or network steering committee in each group. Four working groups were formed based on their recommendations: Individuals, providers, systems, and advocacy. In addition, the discussion groups recommended that at each level we should focus on the following outcomes: a) increase screening rates, b) increase physical activity, c) improve nutrition, and d) increase advocacy. Each of these four groups was charged with finding and reviewing evidenced-based research in these four areas within each level. The goal was to find evidence-based programs at the individual, provider levels and/or systems levels that could be adapted based on the needs and assets available in each county (which were obtained through the inventory described above as well as review of accomplishments from DSN Phase I).

First, the assigned investigator to each working group conducted a review of the pertinent literature, and summarized the findings. The working groups then carried out their charge by meeting to review the evidenced-based literature in their area, inventory of current programs and research in the targeted counties, and previous accomplishments of DSN Phase I. The integration of these components was crucial in understanding the needs and assets in each county and reasons why some evidence-based programs could work and why some could not based on existing resources in the targeted counties.

Once all groups finalized their recommendations, a meeting was held with investigators, staff, and partners to finalize the Community Action Plan. The Community Health Advisors would continue to work to increase cancer screening rates. To address physical activity, a WALK Campaign was suggested as an intervention that had achieved success at a local level through another ongoing effort. WALK Campaign had brought together community, governmental and business groups at a very low cost, and we could expand the model to all targeted counties. “Body and Soul” (Resnicow et al., 2004) was found to have the “best fit” in terms of promoting healthy eating habits. This program could be implemented at the systems level in churches in the DSN communities given the importance of church in these communities. As one of our partners, the American Cancer Society's “Direct Action Organizing” seemed appropriate for the advocacy training that the community requested.

Based on the goals and objectives outlined in the Community Action Plan, a revised evaluation worksheet with the process and outcome evaluation was developed in conjunction with representatives of the Community Health Advisors, Community Network Partners, staff, and investigators. The evaluation component of the plan was developed concomitantly with the development of the activities in a one-day meeting described above. The group decided on the outcomes and how “success” was going to be defined. They also assisted in the development of the assessment tools by providing input on what questions to ask as well as language and length of the assessments. As pointed out earlier, assessments (as well as their length and format) were major concerns among partners and community health advisors throughout the project by emphasizing that the program should not be an “academic exercise” (words of one of the partners). As such, investigators and staff needed to justify the “why” for each question in achieving the established goals. As a result, the baseline and post-test assessments consisted of two pages (front and back) with selected questions.

Community Action Plan Implementation

Once the Community Action Plan was finalized, partners renewed their commitment to the program and began its implementation. In order to implement the plan, all staff went through 3 days of training on each of the 4 program interventions (i.e., WALK, Body and Soul, Screening, and Advocacy). Because of the intensity of the interventions, DSN used a “train the trainer” approach by which the staff would recruit Community Health Advisors and Community Network Partners to serve as Team Leaders for each intervention, and train them with assistance of investigators. The Team Leaders would be responsible for recruiting participants for the targeted intervention, collecting data, maintaining volunteers and other related logistics for the implementation.

Initially, each county was asked to implement each of the four interventions. However, each county would decide on whether they would like to begin with all four or stagger them over time. After the staff training, they spent the next two months providing a detailed overview of each of the interventions with the Community Network Partners and Community Health Advisors. Once the staff begin to do an extensive overview of each project to their local volunteers it became obvious that some of the interventions were received with little to no interest for implementation. Although all counties agreed on the interventions, the community's interest in implementing the programs varied by counties. After receiving this feedback from the communities, it was then decided that each county could decide which of the interventions they would implement and provide a timeline for implementation. Each county was required to implement cancer awareness activities because that was the one area by which they had five years experience as part of DSN Phase I and felt very comfortable with it. However, each county was given an option in implementing the remaining three interventions. If counties selected not to implement an intervention they were asked to submit this information with an explanation.

A detailed step-by-step instruction manual was developed that outline each step necessary for implementing each phase of each of the interventions. Numerous conference calls and meetings were held with the network steering committee and staff at various intervals to provide direction and support to the communities. As mentioned above, partners were represented in the network steering committee and had the responsibility of brainstorming with the Community Network Partners and Community Health Advisors in their respective counties about the ideas being discussed. Each county has unique qualities and weaknesses so we learned valuable lessons from each county as implementation began. For instance, it became apparent that at least two to three staff members needed to be present at each of the kick-off events to assist with data collection and offer technical support to the participants in the completion of the forms. Secondly, the process by which the data was collected differed by county (i.e. small groups vs. group readings vs. formal settings). The process and the staff member's individual group leadership style fostered an environment that was most conducive to greater compliance and member participation. Lastly, the participants' ability to understand and comply with the research process (i.e. completing wellness survey and recording steps,) required multiple efforts for completion and accuracy.

5. Lessons Learned

One of the biggest criticisms to CBPR is its evaluation (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2002). It is argued that this methodology is not rigorous in its application of the scientific methodology, and, therefore, sometimes disregarded by traditional scientists as “outreach activities” which may have impacted the community, but it is not “scientifically sound”. On the other hand, communities tend to agree with these critics since they perceive this type of project as “service” and not “research”. In fact, in our experience they tend to resent “research” because of a long-standing history among underserved communities about “being studied” by the university and not reaping any benefits from the research. As stated by a participant in one of the rural counties in Alabama: “Everyone comes and takes information and samples of soil… but no one ever leaves anything lasting in the community.” As such, we learned three major lessons in the development and implementation of this participatory evaluation plan: (1) the importance of constant and open dialogue among partners; (2) flexibility to make changes in the evaluation plan and implementation; and (3) importance of evaluators playing the role of facilitators between the community and academicians. These lessons are inter-connected and reflects what “participatory” truly means. It is based on equitable relationships among stakeholders, flexibility, commitment from evaluators to the process, and sharing of power (Haviland, 2004; Holte-McKenzie, Forde, & Theobald, 2006; Papineau & Kiely, 1996; Randoph & Eronen, 2007).

Kaplan and Garrett (2005) state that the “… use of the logic model guides program participants in applying the scientific method - the articulation of a clear hypothesis or objective to be tested – to their project development, implementation, and monitoring.” As pointed out by Kaplan and Garrett (2005), the most difficult part of developing the logic model is also its greatest strength. That is, it forces partners from different backgrounds who have conceptualized the project in different ways to come to an agreement early on in the process. The evaluation component is important not only to apply the scientific method, but also to get credibility in these communities. The logic model can act as a “contractual agreement” on what will be done, how it will be done, and how “success” will be measured. Most importantly, the logic model and participatory evaluation can help to get the trust and ownership of disenfranchised communities. By maintaining an open dialogue, we were able to follow the “contract” but also change activities and evaluation tools as they were being implemented.

Another important lesson learned is the need for flexibility. As discussed above, the logic model and measurement of “success” have been fluid in our project and has changed over time. This flexibility contributed to the process of trust and equalization of power since it is not the academic institution dictating how progress and outcomes were being evaluated. Both sides (community and academicians) contribute to the process, and a final product could be obtained without sacrificing the scientific integrity of the project or the integrity of the community. Two examples related to data collection process illustrate the importance of open dialogue, willingness to compromise, and flexibility. As previously stated, there was great resistance from our partners and community health advisors with regard to data collection given their previous experiences with academic settings in which data is collected and the community is neither provided with the results nor a reason for why the data is being collected.

The second example was related to data collection for the WALK campaign. The approach of collecting daily steps registered in the walkers' pedometers through the web was discussed within network and deemed to be the most effective tool. When implemented among over 1,000 walkers across participating counties, we found that in rural counties many walkers did not have easy access to a computer or reliable internet connections, or expressed preference for turning in their steps in paper form. As such, the web-based approach was abandoned and wallet cards were developed.

Flexibility and open dialogue were also crucial within our internal organizational structure. As previously described, investigators and staff decided the WebCT would be the best internal mechanism for communication and sharing of documents. However, as the system was implemented, we found that investigators and staff were not utilizing this technology. When the issue was discussed, they expressed the preference for having discussions over conference calls and sending documents for review through e-mails. In fact most of the progress was made through face-to-face meetings and conference calls. As such, we abandoned this technology at the end of the first year of the project.

Lastly, the role of the evaluators in a traditional research project is to be “neutral” and “detached” from the implementation of the project per se. In a participatory research, evaluators serve as the facilitators or “brokers” between the community and investigators (Nichols, 2002). It was crucial for the evaluators to truly listen to the partners and translate their concerns and suggestions into academic terms and “back translate” the evaluation terms to the community resulting in a product that both parties understood and were comfortable with as evidenced in the examples discussed above.

In summary, participatory evaluation can be both a challenging and rewarding experience. CBPR is a transformative approach rather than unilateral data collection and understanding of a phenomenon. If transformation does not occur, we, as researchers, failed. In most instances this failure is due to lack of equalizing power and true involvement of all parties in the process. Participatory evaluation offers the opportunity to not only assess such transformation through the lens of the scientific inquiry but also through the lens of the target audience who is experiencing the cancer disparities. If this is accomplished, we are truly empowering individuals to overcome disparities.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA U01CA114619).

Biographies

Isabel C. Scarinci, PhD, MPH

Dr. Isabel Scarinci is currently an Associate Professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham's Division of Preventive Medicine. She has had extensive research and clinical experience with underserved populations. Her primary areas of interest are: (1) cancer prevention among low-income, minority (particularly Latinas and African Americans), and immigrant women; and (2) socioeconomic status and health outcomes. Dr. Scarinci is particularly interested in the development and evaluation of community-based programs that are theoretically based and culturally relevant to African Americans and Latinas (particularly immigrants) in the areas of cancer prevention. She has received international, national, and local funding for her work with underserved populations. She has published a number of papers in the areas of health promotion, disease prevention, and mental health among underserved populations, especially low-income and minority women.

Rhoda E. Johnson, PhD

Dr. Rhoda E. Johnson is professor of women's studies at the University of Alabama. Dr. Johnson has completed post doctorate work on minorities and AIDS at the Institute for Survey Research, University of Michigan. Her current work includes projects that focus on empowerment, women's health and community-based participatory research. Her publications include articles on clinical trial retention and recruitment, the development of community action plans, the activities of community health advisors and increasing screening rates for breast and cervical cancer.

Claudia Hardy, MPA

Claudia M. Hardy is the Program Director for the Office of Community Outreach and the Deep South Network for Cancer Control; a five-year funded National Cancer Institute Community Network Program (CNP) awarded to the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Comprehensive Cancer Center. This is the second 5-year community-based, NCI funded program in which Claudia has managed and directed in a senior staff/research capacity. Claudia provides the administrative leadership for this Community-based cancer prevention program that is aimed at eliminating the disparity in cancer death rates between blacks and white in the Deep South. Claudia's areas of interest and expertise are minority health issues/disparities, (community) organizational development, Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR), strategic planning, grants administration, group facilitator/trainer, minority recruitment and retention in clinical trails, access/barriers to health care, program development, special event coordination and consultant to various related health issues. Claudia has trained over 1,000 Community Health Advisors in cancer prevention and control.

John Marron, MA

John Marron is the Data Manager for the Deep South Network for Cancer Control. His training is in Anthropology, Archaeology, and History, and he worked for 20 years as a professional Historical Archaeologist, specializing in the material culture of 16th - 18th c. Spain and Britain, and early European/Native American contact sites in the Southeastern U.S. and Caribbean. His previous experience with medical/sociological research consists of working as Data Manager for five years on a longitudinal study examining the effects of prenatal exposure to cocaine.

Edward E. Partridge, MD

Dr. Edward Partridge is Director of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at The University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is also Associate Director for Cancer Prevention & Control and Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Gynecologic Oncology at UAB. Dr. Partridge is PI of the NCI-funded Deep South Network for Cancer Control, which trains community men and women as Community Health Advisors and Research Partners in an effort to increase cancer awareness in African-American communities in Alabama and Mississippi; PI of the NCI-funded Morehouse School of Medicine/Tuskegee University/UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center Partnership whose goal is to establish a sustainable partnership to eliminate cancer health disparities; and co-investigator on the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Trial investigating screening methodologies for multiple cancers with special emphasis on minority population recruitment.

References

- Adams ML. The African American breast cancer outreach project: partnering with communities. Family and Community Healt. 2007;30(1 Suppl):S85–S94. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (Author et al., 2005).

- Christopher S, Gidley AL, Letiecq B, Smith A, McCormick AK. A cervical cancer community-based participatory research project in a Native American community. Health Education and Behavior. 2007 Dec 12; doi: 10.1177/1090198107309457. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Randolph FL, Kirby MW, Jr, Bebout RR. Creating and using logic models: four perspectives. In: Conrad, editor. Homeless Prevention in treatment of Substance Abuse and mental illness: logic modes and implementation of eight American projects. Philadelphia, PA: The Haworth Press Inc.; 1999. pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Crishna B. Participatory evaluation (I)--sharing lessons from fieldwork in Asia. Child Care Health and Development. 2006;33(3):217–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykeman M, MacIntosh J, Seaman P, Davidson P. Development of a program logic model to measure the processes and outcomes of a nurse-managed community health clinic. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2003;19(4):197–203. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English KC, Fairbanks J, Finster CE, Rafelito A, Luna J, Kennedy M. A socioecological approach to improving mammography rates in a tribal community. Health Education and Behavior. 2006 Dec 22; doi: 10.1177/1090198106290396. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielden SJ, Rusch ML, Masinda MT, Sands J, Frankish J, Envoy B. Key considerations for logic model development in research partnerships: A Canadian case study. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2007;30(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogia do oprimido. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Paz e Terra; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Haviland M. Doing participatory evaluation with community projects. 2004 http://www.aifs.gov.au/sf/pubs/bull6/doing.html.

- Holte-McKenzie M, Forde S, Theobald S. Development of a participatory monitoring and evaluation strategy. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2006;29(2):365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes Halbert C, Weathers B, Delmoor E. Developing an academic-community partnership for research in prostate cancer. Journal of Cancer Education. 2006;21(2):99–103. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2102_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson SP, Dorgan KA, Phillips AN, Behringer B. The mountains hold things in: The use of community research review work groups to address cancer disparities in Appalachia. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2007;34(6):1133–1139. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.1133-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJ, III, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following community based participatory research principles. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan SA, Garrett KE. The use of logic models by community-based initiatives. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2005;28(2):167–172. [Google Scholar]

- Millar A, Simeone RS, Carnevale JT. Logic models: a systems tool for performance management. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2001;24(1):73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health through community organization and community building. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 279–311. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra SI, Bastani R, Crespi CM, Chang LC, Luce PH, Baquet CR. Results of a randomized trial to increase mammogram usage among Samoan women. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007;16(12):2594–2604. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols L. Participatory program planning: including program participants and evaluators. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2002;25(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Papineau D, Kiely MC. Participatory evaluation in a community organization: fostering stakeholder empowerment and utilization. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1996;19(1):79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Randolph JJ, Eronen PJ. Developing the Learning Door: a case study in youth participatory program planning. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2007;30:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, et al. Body and Soul: a dietary intervention conducted through African–American churches. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27(2):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AJ, Christopher S, Lafromboise VR, Letiecq BL, McCormick AK. Apsáalooke women's experiences with pap test screening. Cancer Control. 2008;5(2):166–173. doi: 10.1177/107327480801500209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjasiri SP, Tran JH, Palmer PH, Valente TW. Network analysis of an organizational collaboration for Pacific Islander cancer control. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2007;18(4 Suppl):184–196. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. The conceptual, historical, and practice roots of community based participatory research and related participatory traditions. In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Discussion document on the concept and principles of health promotion. Copenhagen: European Office of the World Health Organization; 1984. [Google Scholar]