Abstract

Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate is a rare variant of prostatic cancer, with less than 100 cases reported in the literature up to date. Tumors are most commonly composed of an admixture of both malignant glandular and spindle cell elements. The sarcomatoid component can vary from 5 to 99%. We report a case of a 76-year old Caucasian man who underwent transurethral resection of the prostate for the treatment of bladder outlet obstruction. Histopathologic examination revealed a tumor with malignant epithelial and sarcomatous elements. The malignant epithelial component consisted of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Gleason score 5+4=9/10) and the sarcomatous component was mainly composed of undifferentiated spindle cells. On immunohistochemistrythe latter expressed a positive staining for vimentin. Several cells were positively stained for cytockeratin AE3 and myoD1 while all were negative for actin, desmin and myogenin. The diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma was finally made. Although sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate is a highly aggressive neoplasm and patients have a poor prognosis, our patient is still alive one year after diagnosis.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, sarcomatoid carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, immunohistochemistry, vimentin, cytokeratin AE1/3

Introduction

Malignant tumors of the prostate that display biphasic patterns are very rare. They include sarcomatoid carcinomas (SC) and carcinosarco-mas (CS) [1]. The admixture of high grade epithelial and sarcomatoid components that characterizes these tumors have led to debate on whether these entities represent a “collision” of epithelial and mesenchymal elements (carcinosarcoma) or an evolution of an underlying adenocarcinoma into a lesion with associated sarcomatoid features and occasional heterologous elements (sarcomatoid carcinoma) [2]. The most recent World Health Organization classification of urinary tract tumor does not distinguish between SC and CS and use the term “sarcomatoid carcinoma” to denote all of these lesions [3]. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate may occur in both adult and elderly patients. Clinically, most patients present with both filling symptoms (frequency, urgency, dysuria, nocturia) and voiding symptoms (poor stream, hesitancy, terminal dribbling, and incomplete voiding). The tumors produce bladder outlet obstruction and often require repeated TURs to control local symptoms [2]. Less frequent manifestations are hematuria, perineal and/or rectal pain and burning on ejaculation. Constipation and constitutional symptoms such as weight loss may also present [4].

We report the case of a 76 years old man with prostate sarcomatoid carcinoma and discuss the clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of this uncommon tumour.

Case report

A 76-year-old man presented to our department with acute urinary retention. He reported no hematuria or perineal pain and denied any constitutional symptoms. A history of frequent micturition, dysuria, poor urinary stream, and nocturia of approximately 12-month duration was also present. There was no family history of genitourinary cancer. He had cessed smoking 10 years ago and drank alcohol socially. He reported no exposure to hazardous chemicals. Rectal examination revealed a moderately enlarged normal prostate gland. There was no palpable lymphadenopathy, and the rest of his physical examination was unremarkable. His last PSA, obtained 3 months earlier by his primary care physician as part of routine annual physical examination, was 3,2 ngr/ml. Since no pathology was found in both physical examination and laboratory tests, he prescribed a-blockers and underwent TWOC three days later. Due to TWOC failure he underwent transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). Patient didn't regain his ability to void four days after surgery and he started on intermittent catheterization.

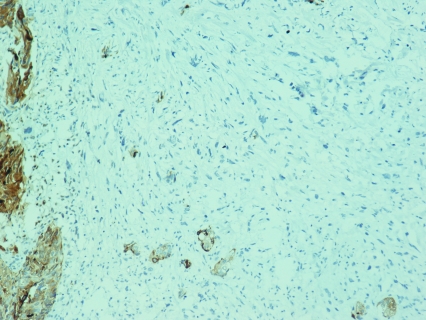

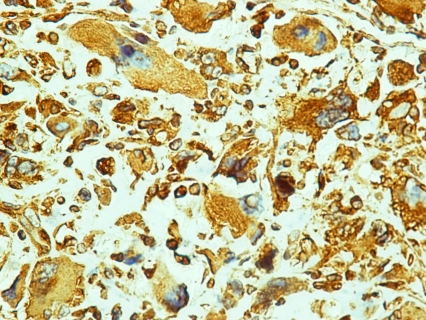

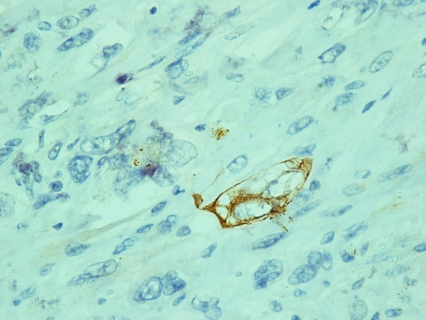

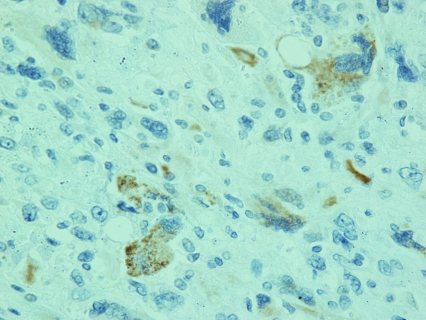

According to the pathology report 40% of the specimen (8cc) contained a biphasic tumor consisted of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 1) and spindle shaped pieomorphic neoplasm while it contained also large areas of necrosis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate. Specifically, carcinomatous element expressed PSAP (Figure 3) but exhibited no staining for PSA and P63. Neoplastic spindle cells expressed vimentin (Figure 4), but exhibited no staining for actin, desmin and P63. Some spindle giant cells were positive for CKAE3 (Figure 5) and MyoD1 (Figure 6).

Figure 1.

Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the prostate (H&E×20).

Figure 2.

Spindle shaped pleomorphic neoplasm (H&E×20).

Figure 3.

Prostate carcinoma expressing PSAP (PSAP×20).

Figure 4.

Spindle cells expressing vimentin (VIM×40).

Figure 5.

A few spindle giant cells positively stained for CKAE3 (CKAE3×40).

Figure 6.

Several spindle giant cells positively stained for MyoD1 (MyoD1×40).

Due to the unexpected findings of the pathology report, patient underwent further evaluation. Computed tomographies of the abdomen, chest and brain as well as bone scan were negative for metastatic disease. Pelvic MRI considered no suspicious for extracapsular extension of the tumor. Although patient was advised to undergo radical prostatectomy he denied any intervention and was discharged home.

Three months later, he presented with urinary retention and acute renal failure. A permanent urinary catheter was placed, and palliative external beam radiotherapy was recommended. One year after final diagnosis patient is still alive.

Discussion

Sarcomatoid carcinoma, also termed carcino-sarcoma and spindle-cell carcinoma, is a rare biphasic malignancy in the prostate [1]. The two elements of SC are a malignant epithelial (carcinomatous) component and a malignant mesenchymal (sarcomatous) component with the presence or absence of heterologous elements [5].

The origin of these tumors has been controversial. It is the consideration of some investigators that SC is merely a collision of sarcoma and carcinoma which develop independently in the prostate. Other investigators however suggested that both components arise from an omnipotent cell. The most recent World Health Organization classification of urinary tract tumors does not distinguish between SC and CS and use the term “sarcomatoid carcinoma” to denote all of these lesions [3].

Microscopically, the carcinomatous and sarcomatous components are admixed, with blending of the two in some areas. The carcinomatous element is almost always of acinar type [5]. Rarely ductal adenocarcinoma [6], squamous or adenosquamous carcinoma [4] and mixed urothelial squamous components [7] are present. Hansel and Epstein reported a Gleason score 6 in 50% of their series and a Gleason score 8 in the remaining 50% [5]. According to Mazzucchelli et al, however, the carcinomatous component is typically of high grade, with a mean Gleason score of 9, and range between 7 and 10 [8].

By immonohistochemistry, epithelial elements react with cytokeratins, PSA, PSAP whereas sarcomatoid elements react with vimentin or specific markers corresponding to the mesenchymal differentiation, if present [9]. Expression of cytokeratin by the spindle cell component of sarcomatoid carcinoma suggests a common origin rather than a collision tumour composed of sarcoma and carcinoma [10].

While the majority of neopiasias of the prostate are not difficult to diagnose, sometimes there is problem in differentiation of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma having a sarcomatoid component, from other tumours having spindle cell morphology such as mixed tumors and primary mesenchymal tumors or benign stromal proliferation [8].

Most patients present with obstructive symptoms (poor stream, hesitancy, terminal dribbling and incomplete voiding) whereas symptoms of frequency, urgency and dysuria, are less common. The tumors produce bladder outlet obstruction and often require repeated TURs to control local symptoms [2]. Serum PSA levels are lower than expected for the tumor volume. On DRE the prostate is enlarged, nodular and hard in most of the reported cases [5]. Diagnosis is usually accomplished by ultrasound guided transrectal needle biopsy which is ordered after an abnormal DRE. Less commonly, diagnosis is obtained by transperineal biopsy, CT guided biopsy, TUR-P or suprapubic prostatectomy. Due to the excessive tumor's ability to spread out of the prostate and metastasize in bones liver and lung a subset of patients are diagnosed with late stage disease.

Due to the limited experience, there are no standard treatment recommendations the management of CSs of the prostate. Operable tumors are treated with surgery, which may be followed by radiation therapy and/or adjuvant chemotherapy, particularly in patients with positive margins or nodes [5]. Surgeries with curative intent include radical retropubic prostatectomy, radical cystoprostatectomy, suprapubic prostatectomy, and pelvic exenteration. Patient with SC have poor prognosis, with an actual risk of death of 20% within one year of diagnosis. In fact, non-surgical therapy (androgen ablation treatment and chemotherapy) seems to be ineffective and 55.5% of patients are unresponsive to chemotherapy (taxotere, estramustine, car-boplatinum, or cisplatinum) [5]. In conclusion, SC of the prostate is an exceedingly rare tumor. Retrospective analyses render prostate SC as one of the most aggressive prostate malignancies. The prognosis is dismal regardless of other histologic or clinical findings.

References

- 1.Mostofi FK, Price EB. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of Male Genital System, series 2, part 8. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1973. Malignant tumors of the prostate; pp. 257–258. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grignon DJ. Unusual subtypes of prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2004;17(3):316–27. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Classification of Tumors, editor. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berney DM, Ravi R, Baithun SI. Prostatic carcino-sarcoma with squamous cell differentiation: a consequence of hormonal therapy. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Urol Pathol. 1979;11:123–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansel DE, Epstein JI. Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate: a study of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1316–21. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000209838.92842.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poblet E, Gomez-Tierno A, Alfaro L. Prostatic carcinosarcoma: a case originating in a previous ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196:569–72. doi: 10.1016/s0344-0338(00)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers CG, Parwani A, Tekes A, Schoenberg MP, Epstein JI. Carcinosarcoma of the prostate with urothelial and squamous components. J Urol. 2005;173:439–40. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000149969.76999.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzucchelli R, Lopez-Beltran A, Cheng L, Scarpelli M, Kirkali Z, Montironi R. Rare and unusual histological variants of prostatic carcinoma: clinical significance. BJU Int. 2008;102(10):1369–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wick MR, Brown BA, Young RH, Mills SE. Spindle-cell proliferations of the urinary tract: an immu-nohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:379. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198805000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray ME, Wojno KJ, Goldstein NS, Olson K, Shah R, Cooney K. Clonality of sarcomatous and carci-nomatous elements in sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate. Urology. 2006;67:423. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.013. e5-e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]