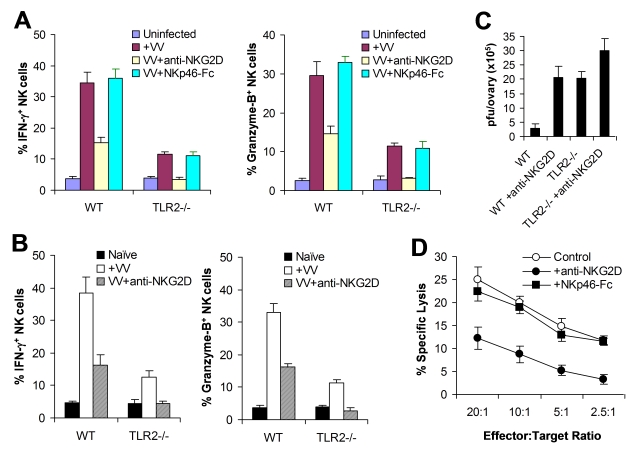

Figure 6. The NKG2D pathway is required for efficient NK activation and function in response to VV infection.

(A) WT or TLR2−/− DX5+CD3− NK cells were co-cultured with WT CD11c+ DCs and stimulated with VV alone (+VV), VV in the presence of anti-NKG2D (VV+anti-NKG2D) or NKp46-Fc chimera (VV+NKp46-Fc), or left uninfected (Uninfected). 24 hr later, NK cells were assayed for intracellular IFN-γ and Granzyme B. The mean percentage ± SD of IFN-γ or Granzyme B positive cells among DX5+CD3− cells is shown. (B–C) WT or TLR2−/− mice were infected with VV (+VV) or left uninfected (Naïve). Some mice were pre-treated with anti-NKG2D antibodies 24 and 6 h prior to infection with VV (VV+anti-NKG2D). 48 h after infection, splenic NK cells were analyzed for IFN-γ and Granzyme B production. The mean percentage ± SD of IFN-γ or Granzyme B positive cells among DX5+CD3− cells is indicated (n = 4 per group) (B). The ovaries of female mice were harvested for measurement of viral load. Data represents the mean viral titer ± SD as pfu per ovary (n = 4 per group) (C). (D) 48 h after infection, splenocytes from WT mice were assayed for NK cell lytic activity on VV-infected L929 cells in the presence of anti-NKG2D antibodies (+anti-NKG2D) or NKp46-Fc chimera (+NKp46-Fc), for 4 hr at different effector∶target ratios. The mean percentage ± SD of specific lysis is indicated (n = 4 per group). Data shown is representative of two independent experiments.