Abstract

A growing literature on the social determinants of health strongly suggests the value of examining social policy interventions for their potential links to health equity. I investigate how sectoral job training, an intervention favored by the Obama administration, might be conceptualized as an intervention to improve health equity. Sectoral job training programs ideally train workers, who are typically low income, for upwardly mobile job opportunities within specific industries. I first explore the relationships between resource redistribution and health equity. Next, I discuss how sectoral job training theoretically redistributes resources and the ways in which these resources might translate into improved health. Finally, I make recommendations for strengthening the link between sectoral job training and improved health equity.

From its earliest days, the practice of public health has been animated by its link with economic production and the compelling nature of the stepwise relationship between socioeconomic position and health, now called the social gradient in health.1 Research in social epidemiology indicates that it is not only absolute income or wealth that matters in shaping health; various forms of inequality are also correlated with poor health and diminished health equity.2 Responding to these studies, public health researchers and practitioners have long wondered with James Colgrove, who wrote in the Journal in 2002,

Are public health ends better served by targeted interventions or by broad-based efforts to redistribute the social, political, and economic resources that determine the health of populations?3

Although most researchers within public health would agree that both approaches are necessary, the vast majority of intervention research in public health focuses on targeted health interventions rather than on the social, political, and economic conditions that put people at “risk of risks”4 and the redistributive policies that might alter these conditions.

These latter “social determinants of health” have reached new levels of prominence with the publication of the World Health Organization's 2008 report on health equity and the social determinants of health. In the report's introduction, the authors wrote,

[The] unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a “natural” phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and programmes, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics. Together, the structural determinants and conditions of daily life constitute the social determinants of health and are responsible for a major part of health inequities between and within countries.5

Such a statement, along with the detailed recommendations made by the authors, strongly suggests the value of examining social policy interventions, especially those that affect daily life and redistribute resources, for their potential links to health equity. In this article, I examine the ways in which one type of social policy intervention—sectoral job training—might be conceptualized as an intervention to improve health equity. Sectoral job training programs ideally train workers, who are typically low income, for upwardly mobile job opportunities within specific industries. I first explore how resource redistribution can be defined in relation to improving equity in health. I next discuss how sectoral job training theoretically redistributes resources and the pathways through which such resource redistribution might translate into improved health. Finally, I make recommendations for strengthening the link between sectoral job training and improved health and health equity.

RESOURCE REDISTRIBUTION AND EQUITY IN HEALTH

Reflecting an interest in structural influences on health, numerous researchers have investigated the relationship between income inequality and population health.6 This large body of literature seems to favor the finding that, in the United States, income inequality is correlated with poorer average health across large geographic areas (typically, metropolitan areas or larger).7 Debate continues, however, about the strength and even the existence of the relationship, especially internationally.8 Although income inequality appears important in the production of population health, many researchers have argued that income inequality is just one form of inequality that may matter for health outcomes. Other forms of inequality—notably those related to power, race, and class—also have been shown to influence the health of societies.9

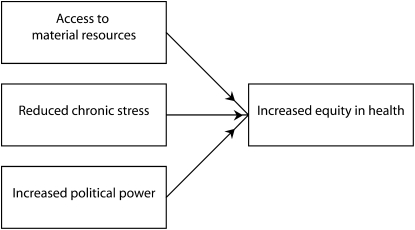

A basic model10 was described by Starfield and Birn11 that recognizes the multiple mechanisms of inequality through which health inequities are produced. They wrote that equity in health can be produced via 3 or more pathways, which seek respectively to (1) “improve access to health-inducing material goods (better nutrition, housing, education, medical care services),” which here I call “access to material resources”; (2) “ameliorate psychological stress stemming from perceived social exclusion and the resulting neuro-endocrine-immune mechanisms that predispose to illness,” which I call “reduced chronic stress”; and (3) “enable increased political power (and control of resources) on the part of working class and socially excluded populations,” which I call “increased political power.”12 These mechanisms, which are supported in the literature, are graphically illustrated in Figure 1 and described in more detail later in this article.

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms producing equity in health.

Regarding the first pathway, research has long emphasized the need for a certain amount of material resources for basic healthy living, a position that is consistent with the “neo-materialist” hypothesis of the relationship between income and health. This interpretation highlights the ability that income confers on individuals to purchase health-inducing goods and services such as health insurance, safe and healthy housing, and nutritious foods.13 As for the second pathway, researchers have posited that low social status is associated with lower control (especially in employment settings) and reduced ability to participate in society,14 as well as the lived experience of “inferiority,”15 all of which produce chronic stress. A wide range of possible sources of chronic stress associated with low social status have been studied.16 The psychosocial mechanisms producing these various forms of chronic stress have physiological implications as well, because they produce “wear and tear” (or allostatic load)17 on physiological systems that must constantly adapt to stressors. Over time, allostatic load can lead to disease across multiple biological systems.18

Regarding the third pathway, researchers studying political and economic systems have repeatedly theorized and demonstrated the role played by lack of political and economic power among the working classes as integral to the production of health inequalities.19 One researcher in particular, Thomas LaVeist, finds that a relatively higher level of African American political power (as measured by the proportion of African Americans on city councils divided by the proportion of African Americans in the voting-age population) is correlated with lower African American postneonatal mortality rates. He also notes that White postneonatal mortality rates do not change with increasing African American political power. Thus, in this case, increased political power among African Americans is associated with reduced Black–White health inequalities.20

In speculating about the mechanisms of this relationship, LaVeist suggests that “community organization” in the form of politicized action may have a role. This is in line with a recent article reporting on the work of the World Health Organization's knowledge networks, which underscored the importance of engaged civil society organizations and coalitions, including labor unions and social movements (for instance, advocating for environmental justice), in working toward social, political, and economic changes that can nurture health equity.21

The implication of Starfield and Birn's model is that income redistribution alone—through standard redistributive policies such as taxation, cash transfers, and a minimum wage—is unlikely to reduce health inequities as it addresses only the first of these pathways.22 Job training, when implemented successfully, may achieve both economic redistribution (by distributing work opportunities to those who have not traditionally had access to them) and associational redistribution, in which governments “intervene to alter how groups are formed in the economy and in the broader society.”23 In this model, associational redistribution speaks to the importance of being an employed member of society for reducing certain forms of chronic stress and increasing political power. Because the model addresses redistribution of material goods, opportunities, associations, and power, I refer to shifts in all 3 of its pathways as “resource” redistribution.

JOB TRAINING AND EQUITY IN HEALTH

There are several reasons to consider the relationship of job training to equity in health. First, job training, unlike other policy interventions for redistributing income alone, also aims to improve the education level, employment level and wages, and ideally the class position of the poor and working-class populations that it trains. Thus, job training as an intervention addresses all 3 of Starfield and Birn's pathways.

One could point to examples of job training programs that appear to be having many of these effects. Seattle's Apprenticeship Opportunities Project (AOP), for instance, increased the demand for construction apprentices by passing city policies requiring certain percentages of apprentice labor hours (including specific requirements for racial/ethnic minorities and women) on large public construction projects. The AOP also increased the supply of apprentices by training people to fill these positions. The apprenticeships and jobs in which participants ultimately were placed offered an average wage of over $12 per hour.24 The program thus increased the skill levels, employment opportunities, and levels of employment, and ideally over time it will improve the class position of a large group of disadvantaged workers. In conjunction with these changes, workers may gain better access to health-inducing material goods, reduced chronic stress, and increased political power.

A second reason is that populations of public health concern are often also those that are targeted by and seeking job training programs. As suggested by the description of the AOP, job training programs often concentrate their work on disadvantaged minority populations. This concentration may happen intentionally, as in the case of the AOP, or unintentionally via neighborhood-based or income-based applicant criteria that are correlated with minority race/ethnicity. Race has emerged as a particularly salient characteristic in producing health inequality through such proposals as the “weathering” hypothesis of Arline Geronimus et al., which posited that

Blacks experience early health deterioration as a consequence of the cumulative impact of repeated experience with social or economic adversity and political marginalization.25

Their research shows that African Americans have higher levels of damage to biological systems than do White populations throughout the life course and that these differential levels are not explained by differences in rates of poverty.26 Thus, if job training can improve conditions of social, economic, and political adversity for minority populations, it may also help to arrest the effects of weathering. In addition, the process of training itself may provide an opportunity for programs to help enhance access to health services directly, by linking disadvantaged trainees to state-subsidized health services or insurance.27

A third reason is that, as others have pointed out,28 political feasibility plays a key role in considering which policies may be worth examining in conjunction with population health. Education and training initiatives have emerged as a major area of policy interest for the Obama administration. Progressive policy analysts lauded the administration's inclusion of increased funding for education and training in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, arguing that “education and training can thus be both an effective short-term stimulus and a long-term investment in the economy.”29 Building on this, in July 2009, the administration announced a $12 billion initiative to support community colleges in their efforts to train and retrain their student population of mostly working adults for “jobs of the future.”30 Sector-focused training programs are cited in particular in the accompanying report as a “promising approach” to building a more effective training system.31

SECTORAL JOB TRAINING

Of the many types of job training programs currently in operation throughout the United States, sectoral approaches to job training and workforce development have become increasingly popular over the last decade. These programs focus on training workers for a single industry and, usually, a single job type. Trainers, often working closely with community colleges, may develop curricula in conjunction with industry employers to ensure that trainees have the appropriate skills for employment upon completion. Although sectoral approaches to workforce development may have originally been focused on higher-skilled jobs,32 there has been an increasing interest in using sectoral programs to train low-skilled and poor workers.33 If such programs are successful in training these populations to work in local growth industries, they comprise a much-touted “win-win” situation, in which poor but newly skilled workers are used to attract increased business development around a particular industry, while at the same time these populations gain access to jobs and advancement opportunities.34

Sectoral programs operate through 2 primary mechanisms: (1) working with low-income or low-skilled individuals through job training programs and (2) working within local industry and policy environments to engage in systems change that will allow trainees to be placed in high-quality jobs. The Aspen Institute outlined 3 domains of change that sectoral initiatives might undertake toward this latter goal: (1) changing industry practices around recruitment, training, promotion, and compensation; (2) improving the education and training system; and (3) altering public policy relating to workforce, education, labor, and business practices.35

In defining “high-quality” jobs, I take a cue from the criteria by which sectoral programs' job placements are judged. An evaluation of 6 sectoral training programs from around the country suggests that a “high-quality job” should involve (1) a combination of earnings per hour and hours of work that results in annual earnings above the poverty level; (2) work patterns that are steady throughout the year and that do not require “patching” or holding more than one job simultaneously; (3) the provision of benefits such as health insurance, paid vacation, paid sick leave, a pension, and ongoing paid training opportunities; and (4) work that participants find satisfying. An additional aspect of high-quality jobs is connected to advancement, often through the development of career ladders that

lay out a sequence of connected skill upgrading and job opportunities, with each education step on the ladder leading to a job and/or further education or training.36

Sectoral training programs may be more likely to achieve their goals when career ladders are well defined, although it appears possible for programs to succeed without the development of career ladders.37

I focus on effective sectoral employment initiatives because they have a potentially strong ability to redistribute resources. Although the reach of sectoral employment initiatives is somewhat limited because a great deal of work is required to establish partnerships between trainers and industry, the number of these programs has grown significantly in recent years, increasing from several dozen across a few industries in the 1990s to more than 200 across more than 20 industries in 2007.38 Government funding for these programs has increased, and these programs have increasingly become institutionalized via collaborations with community colleges, local workforce oversight boards, and business associations.39 Sectoral programs are also highly politically feasible under the current administration, which conceptualizes workforce development as catering both to workers and businesses.40

In part because these programs require a great deal of coordination, however, it is difficult to implement them faithfully according to these models. Given this problem, although evaluations of sectoral job training programs indicate some success in increasing earnings for those who complete these programs, they also indicate that many trainees drop out before completing programs.41 In a large-scale evaluation of federally funded sectoral initiatives, Pindus et al. found that, because of funding and time constraints, many grantee organizations focused primarily on business or industry needs and trained a target population that could be easily prepared to meet these needs: “While these projects may have been quite useful to the workers involved, they were less likely to involve hard-to-serve populations.”42 A reverse problem has also been known to arise in the implementation of sectoral training programs. In this case, although the focus remains on “hard-to-serve” workers, the training program does inadequate work to advance systemic changes within the industry that will allow these workers to find jobs and move up.43 In both of these cases, the promise of sectoral job training for low-skilled workers is not fulfilled; in the first case, because low-skilled workers may no longer be eligible for the program, and in the second because low-skilled workers may have difficulty finding stable work in the industry following the program.

POSSIBLE PATHWAYS LINKING SECTORAL TRAINING AND EQUITY IN HEALTH

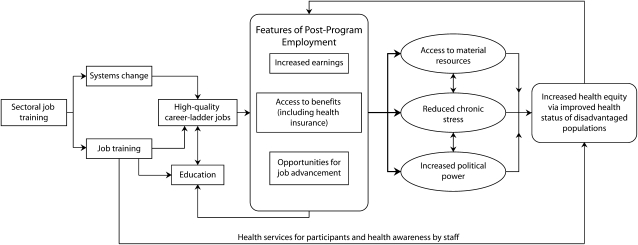

One model for the pathway between sectoral job training and health equity, which builds on the relationship between resource redistribution and health outlined earlier, is shown in Figure 2. The thicker arrows in the diagram show the relationships between the ideal outcomes of sectoral job training programs and the pathways toward health equity. The model is primarily focused on dynamics that are relevant to the experiences of individuals participating in sectoral training programs, although the larger a population such programs can address, the greater the potential impact on health equity.

FIGURE 2.

Pathways between sectoral job training and increased equity in health.

Beginning with the first pathway, research and theory support the linking of earnings, benefits, and job advancement with material resources. As mentioned in the “Resource Redistribution and Equity in Health” section, the rationale behind the neo-materialist interpretation of the link between income inequality and population health is that increased income allows individuals to purchase goods and services that improve health, such as health insurance, housing, more nutritive foods, and even gym memberships.44 Employer-provided benefits such as health insurance subsidies, paid sick leave, and paid vacation all serve to provide economic security,45 thus helping to maximize access to health-related material resources. Similarly, because of the increased earnings and typically increased benefits associated with job advancement, advancement up a career ladder will likely also improve access to material resources.

Employment of the kind described here probably also reduces certain sources of chronic stress. Researchers define chronic stress as spanning multiple possible domains, including the domains of occupation, finances, marriage, family, social life, housing, health, race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation.46 Logic suggests that some forms of chronic stress (financial, at the very least) are likely to accompany the experience of unemployment for most people. Because sectoral job training programs typically cater to those who are unemployed, program participation and subsequent employment may reduce these forms of chronic stress.47 However, the features of jobs in which trainees are placed may have important implications for stress as well, as recent studies have found that less secure jobs are related to psychological distress48 and fatigue.49 Indeed, a systematic review indicates that although some interventions to improve employee control at work have beneficial health effects, such interventions are unlikely to protect employees from the health effects of job insecurity.50 Additionally, even if secure, work itself may generate its own chronic stressors because of unfavorable ratios of job demands, job control, and support on the job, which in turn have negative health implications.51 Although unfavorable ratios and poor working conditions are not consistent with the kinds of labor that sectoral job training programs aspire to, they serve as a reminder that job placements offering unfavorable ratios of demands, control, and support (for instance, high demands, low control, and low support) diminish the ability of such programs to improve health.

Employment resulting from effective sectoral job training programs may also increase the political power of populations participating in sectoral job training. Vicente Navarro argued that such power is critical to health equity. In his research, Navarro used electoral behavior and trade union characteristics as indicators of political power.52 Although we lack data to speculate about entry into union labor associated with sectoral training programs, it is possible to theorize about changes in electoral behavior associated with employment. Census data indicate that those in the overall labor force vote at higher rates (65.2% in 2008) than those who are unemployed (54.7%).53 Voter registration and voting rates also increase steadily with increasing income and educational attainment.54 Provided that sectoral job training programs move people up a career ladder through continued training and education, this may hold true for sectoral program graduates as well.

MAXIMIZING THE IMPACT OF SECTORAL TRAINING PROGRAMS ON HEALTH EQUITY

As the discussion of the pathways between sectoral job training and improved health equity suggests, the model is very much dependent on the ideal functioning of sectoral job training programs. This situation leads to a proposal of several recommendations regarding the implementation of these programs.

Recommendations for Optimizing Sectoral Approaches

There are a number of actions that local governments, workforce stakeholders, and job training programs can take to optimize sectoral approaches.

First, local governments can ensure that sectoral job training programs serve the low-income, low-skilled populations they theoretically target. This is in keeping with the admonishment in the Council of Economic Advisers' report that training programs should not “cream skim.”55 Creating further advantages for those who already have some advantage in the world of employment will increase disparities in resources of the kind discussed in this article.

Second, local governments can encourage sectoral job training programs to engage in the kinds of “systems change”56 required to ensure that high-quality, career-ladder jobs are available for graduates. Bennett and Giloth provide several specific recommendations for accomplishing this in their study of social equity and economic development in 5 American cities. These recommendations included working with other workforce players to construct career pathways in growth industries and making sure that economic incentives offered to private industry are contingent on wage and job quality guarantees, first-source hiring, and workforce development contributions.57 Additionally, as Geronimus et al.'s research indicates, if being African American in a racist society is what drives the weathering phenomenon,58 then sectoral job training programs that place African American participants in racist workplaces will not improve health. To the extent possible, non–racially discriminating workplaces should be cultivated as part of sectoral “systems change.”

Third, they can work to bring industries that may offer healthy, high-quality, career-ladder jobs to entry-level workers to the region. As Bennett and Giloth wrote of the cities in their study, “None of our case study cities challenged the nature of economic growth that was occurring. … [F]or the most part, our cities tried to compete for the economy before them.”59 This failure to engage in debates around the social impact of economic development has implications for the kind of work that is available for trainees, which in turn has implications for both job outcomes and health.

Recommendations for Optimizing Job Training for Health Improvement

Job training programs can optimize job training for improved health by taking the following actions. First, they can ensure that training program staff deal with participants' existing health issues in ways that are supportive of trainees. Throughout sectoral job training programs, students are asked to show that they will make good employees in the target industry by demonstrating proper “demeanor, professionalism, and self-discipline.”60 Successfully performing these dispositions and modes of behavior may require trainees who live with chronic illness, for instance, to present their illnesses in particular ways. These presentations are unlikely to have beneficial clinical outcomes in the absence of access to health care, and may affect the ability of trainees to remain in the workforce following job placement. Thus, whether training programs can provide access to health services for their trainees, program staff should attend to the performative demands of their programs and the potential role of health in these performances.

Second, training programs can link trainees to services to improve health during training. Chronic illness, injury, and other kinds of health problems are prevalent among the low-income and minority populations often targeted by sectoral job training programs. These health issues can create a major barrier to completing training and finding work. Although job training programs often note resource limitations as a reason for not providing health services, programs that do provide them frequently find that these kinds of “support services” are integral to the success of low-income participants in completing training and job placement.61

CONCLUSIONS

Sectoral training programs, whether part of urban development initiatives or federal educational and training efforts, appear to comprise a workforce development approach with increasing popularity and reach. However, the success of these programs depends on a complex array of factors, which have been summarized here. Likewise, an important set of outcomes depends on these programs' success. Implemented well and with attention to the recommendations given here, sectoral training programs provide an unprecedented opportunity to potentially improve not only the employment, incomes, and educational levels of historically disadvantaged populations, but also their health and the health equity of the areas in which they live.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Johns Hopkins Sommer Scholars program for financial support during the preparation of this article.

I am very grateful to Lori Leonard, Laura Steinhardt, and David Holtgrave for support and thoughtful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Human Participant Protection

The study associated with this research was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's institutional review board.

Endnotes

- 1. Marmot, M, “Achieving Health Equity: From Root Causes to Fair Outcomes,” Lancet 370 (9593) (2007): 1153–1163; Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. Wilkinson, R. G., and K. E. Pickett, “Income Inequality and Population Health: A Review and Explanation of the Evidence,” Social Science and Medicine 62 (7) (2006): 1768–1784; Ash, M., and D. E. Robinson, “Inequality, Race, and Mortality in US Cities: A Political and Econometric Review of Deaton and Lubotsky (56:6, 1139–1153, 2003),” Social Science and Medicine 68 (11) (2009): 1909–1913, discussion 1914–1917; Deaton, A., and D. Lubotsky, “Mortality, Inequality and Race in American Cities and States,” Social Science and Medicine 56 (6) (2003): 1139–1153; Muntaner, C., and J. Lynch, “Income Inequality, Social Cohesion, and Class Relations: A Critique of Wilkinson's Neo-Durkheimian Research Program,” International Journal of Health Services 29 (1) (1999): 59–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3. Colgrove, J., “The McKeown Thesis: A Historical Controversy and Its Enduring Influence,” American Journal of Public Health 92 (5) (2002): 725–729, quote from p. 725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Link, B. G., and J. Phelan, “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior (special no.) (1995): 80–94. [PubMed]

- 5. Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Closing the Gap in a Generation, 1.

- 6. Wilkinson and Pickett, “Income Inequality and Population Health”; Muntaner and Lynch, “Income Inequality, Social Cohesion, and Class Relations”; Subramanian, S., and I. Kawachi, “Being Well and Doing Well: On the Importance of Income for Health. Int J Soc Welf. 15(suppl 1) (2006):S13–S22; Mackenbach, J., “Evidence Favouring a Negative Correlation Between Income Inequality and Life Expectancy Has Disappeared,” British Medical Journal 324 (7328) (2002): 1–2; Diez-Roux, A. V., B. G. Link, and M.E. Northridge, “A Multilevel Analysis of Income Inequality and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors,” Social Science and Medicine 50 (5) (2000): 673–687; Lynch, J., G. D. Smith, S. Harper, and M. Hillemeier, “Is Income Inequality a Determinant of Population Health? Part 2: US National and Regional Trends in Income Inequality and Age- and Cause-Specific Mortality,” Milbank Quarterly 82 (2) (2004): 355–400; Lynch, J., G. D. Smith, S. Harper, et al., “Is Income Inequality a Determinant of Population Health? Part 1: A Systematic Review,” Milbank Quarterly 82 (1) (2004): 5–99; Marmot, M., “The Influence of Income on Health: Views of an Epidemiologist,” Health Affairs 21 (2) (2002): 31–46; Rodgers, G., “Income and Inequality as Determinants of Mortality: An International Cross-Section Analysis,” Population Studies 33 (1979): 343–351; Subramanian, S. V., T. Blakely, and I. Kawachi, “Income Inequality as a Public Health Concern: Where Do We Stand? Commentary on ‘Is exposure to income inequality a public health concern?’ ” Health Services Research 38 (1 pt 1) (2003): 153–167; Subramanian, S. V., and I. Kawachi, “The Association Between State Income Inequality and Worse Health Is Not Confounded by Race,” International Journal of Epidemiology 32 (6) (2003): 1022–1028; Subramanian, S. V., and I. Kawachi, “Income Inequality and Health: What Have We Learned So Far?” Epidemiologic Reviews 26 (2004): 78–91; Subramanian, S. V., and I. Kawachi, “Commentary: Chasing the Elusive Null—The Story of Income Inequality and Health,” International Journal of Epidemiology 36 (3) (2007): 596–599; Wagstaff, A., and E. van Doorslaer, “Income Inequality and Health: What Does the Literature Tell Us?” Annual Review of Public Health 21 (2000): 543–567.

- 7. Wilkinson and Pickett, “Income Inequality and Population Health”; Wilkinson, R. G., “Comment: Income, Inequality, and Social Cohesion,” American Journal of Public Health 87 (9) (1997): 1504–1506; Bishai, D., and Y.-T. Kung, “Macroeconomics,” in Macrosocial Determinants of Population Health, ed. S. Galea (New York: Springer Science and Business Media, 2007), 169–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Lynch et al., “Is Income Inequality a Determinant of Population Health? Part 1”; Deaton, A., “Health, Inequality, and Economic Development,” Journal of Economic Literature 41 (2003): 113–158.

- 9. Ash and Robinson, “Inequality, Race, and Mortality in US Cities”; Deaton and Lubotsky, “Mortality, Inequality and Race in American Cities and States”; Muntaner and Lynch, “Income Inequality, Social Cohesion, and Class Relations”; Navarro, V., and L. Shi, “The Political Context of Social Inequalities and Health,” Social Science and Medicine 52 (3) (2001): 481–491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10. Starfield elaborates a more detailed model in “Pathways of Influence on Equity in Health,” Social Science and Medicine 64 (7) (2007): 1355–1362. While this more detailed model and the research recommendations associated with it are both of interest, for the purposes of developing a model linking sectoral job training and health, my goal is to give a sense of how such programs might affect the basic pathways associated with resource inequality and health, rather than providing detailed speculation about how such programs might affect more nuanced pathways at multiple levels. The hope is that this exercise in basic model development will serve as a foundation from which more detailed investigations of particular sectoral training programs might develop. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. Starfield, B., and A. E. Birn, “Income Redistribution Is Not Enough: Income Inequality, Social Welfare Programs, and Achieving Equity in Health,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61 (12) (2007): 1038–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Ibid, 1039.

- 13. Subramanian and Kawachi, “Being Well and Doing Well”; Morris, J. N., A. J. Donkin, D. Wonderling, P. Wilkinson, and E. A. Dowler, “A Minimum Income for Healthy Living,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 54 (12) (2000): 885–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Marmot, M. G., “Status Syndrome: A Challenge to Medicine,” Journal of the American Medical Association 295 (11) (2006): 1304–1307. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Wilkinson and Pickett, “Income Inequality and Population Health”; Charlesworth, S. J., P. Gilfillan, and R. Wilkinson, “Living Inferiority,” British Medical Bulletin 69 (2004): 49–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16. Thoits, P. A., “Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes: Where Are We? What Next?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior (special no.) (1995): 53–79; Turner, R. J., B. Wheaton, and D. A. Lloyd, “Epidemiology of Social Stress,” American Sociological Review 60 (1) (1995): 104–125; Meyer, I. H., S. Schwartz, and D. M. Frost, “Social Patterning of Stress and Coping: Does Disadvantaged Social Statuses Confer More Stress and Fewer Coping Resources?” Social Science and Medicine 67 (3) (2008): 368–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. McEwen, B. S., and T. Seeman, “Protective and Damaging Effects of Mediators of Stress. Elaborating and Testing the Concepts of Allostasis and Allostatic Load,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 896 (1999): 30–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Ibid.

- 19. Muntaner and Lynch, “Income Inequality, Social Cohesion, and Class Relations”; Navarro, V., “What We Mean by Social Determinants of Health,” International Journal of Health Services 39 (3) (2009): 423–441; Coburn, D., “Beyond the Income Inequality Hypothesis: Class, Neo-Liberalism, and Health Inequalities,” Social Science and Medicine 58 (1) (2004): 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. LaVeist, T. A., “The Political Empowerment and Health Status of African-Americans: Mapping a New Territory,” American Journal of Sociology 97 (4) (1992): 1080–1095.

- 21. Blas, E., L. Gilson, M. P. Kelly, et al., “Addressing Social Determinants of Health Inequities: What Can the State and Civil Society Do?” Lancet 372 (9650) (2008): 1684–1689. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Starfield and Birn, “Income Redistribution Is Not Enough.”

- 23. Durlauf, S. N., “The Memberships Theory of Poverty: The Role of Group Affiliations in Determining Socioeconomic Outcomes,” in: Understanding Poverty, ed. S. H. Danziger and R. H. Haveman (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2001), 392–416, quote from p. 410.

- 24. Watrus, B., and J. Haavig, “Seattle's Best Practices in the 1990s: Municipal-Led Economic and Workforce Development,” in: Economic Development in American Cities: The Pursuit of an Equity Agenda, ed. M. I. J. Bennett and R. P. Giloth (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), 111–132.

- 25. Geronimus, A. T., M. Hicken, D. Keene, and J. Bound, “ ‘Weathering’ and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores Among Blacks and Whites in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 96 (5) (2006): 826–833, quote from p. 826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Ibid.

- 27. As is shown in Figure 2, access to care that training programs may provide or improve directly links to increased health equity.

- 28. Low, M. D., B. J. Low, E. R. Baumler, and P. T. Huynh, “Can Education Policy Be Health Policy? Implications of Research on the Social Determinants of Health,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 30 (6) (2005): 1131–1162. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29. Holzer, H. J., Do Education and Training Belong in the Recovery Package? (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2009), 2.

- 30. Council of Economic Advisers, “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow,” July 2009, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/Jobs-of-the-Future, accessed December 22, 2009; J. Rutenberg, “Obama Attacks on Economy and Seeks Billions for Community Colleges,” New York Times, July 14, 2009 available at http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/15/us/politics/15obama.html, accessed December 22, 2009.

- 31.Council of Economic Advisers, “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow.”

- 32. Giloth, R. P., “Investing in Equity: Targeted Economic Development for Neighborhoods and Cities,” in: Economic Development in American Cities: The Pursuit of an Equity Agenda, ed. M. I. J. Bennett and R. P. Giloth (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), 23–50.

- 33. Conway, M., A. Blair, S. L. Dawson, and L. Dworak-Muñoz, Sectoral Strategies for Low-Income Workers: Lessons From the Field (Washington, DC: Workforce Strategies Initiative, The Aspen Institute, 2007)

- 34. Ibid; Zandniapour, L., and M. Conway, Gaining Ground: The Labor Market Progress of Participants of Sectoral Employment Development Programs Washington (Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute, Economic Opportunities Program, 2002)

- 35. Conway, M., A. Blair, A. Gerber, Systems Change (Washington, DC: Workforce Strategies Initiative, The Aspen Institute, 2008)

- 36. Zandniapour and Conway, Gaining Ground; Holzer, H. J., and K. Martinson, Can We Improve Job Retention and Advancement Among Low-Income Working Parents? (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2005), 13.

- 37.Conway et al., Sectoral Strategies for Low-Income Workers.

- 38. Conway, M., Sectoral Strategies in Brief (Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute, 2007)

- 39. Ibid.

- 40.Council of Economic Advisers, “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow.”

- 41. Pindus, N. M., C. O'Brien, M. Conway, C. Haskins, and I. Rademacher, Evaluation of the Sectoral Employment Demonstration Program: Final Report (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2004)

- 42. Ibid, 52.

- 43.Conway et al., Systems Change.

- 44.Subramanian and Kawachi, “Being Well and Doing Well.”

- 45. Employee Benefit Research Institute. “EBRI Databook on Employee Benefits,” 2008, available at http://www.ebri.org/pdf/publications/books/databook/DB.Chapter%2001.pdf, accessed December 22, 2009.

- 46.Thoits, “Stress, Coping, and Social Support Processes”; Turner et al., “Epidemiology of Social Stress”; Meyer et al., “Social Patterning of Stress and Coping.”

- 47. Turner, H. A., “The Significance of Employment for Chronic Stress and Psychological Distress Among Rural Single Mothers,” American Journal of Community Psychology 40 (3–4) (2007): 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Ferrie, J. E., M. J. Shipley, K. Newman, S. A. Stansfeld, and M. Marmot, “Self-Reported Job Insecurity and Health in the Whitehall II Study: Potential Explanations of the Relationship,” Social Science and Medicine 60 (7) (2005): 1593–1602; Artazcoz, L., J. Benach, C. Borrell, and I. Cortes, “Social Inequalities in the Impact of Flexible Employment on Different Domains of Psychosocial Health,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 (9) (2005): 761–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49. Bultmann, U., I. J. Kant, C. A. Schroer, and S. V. Kasl, “The Relationship Between Psychosocial Work Characteristics and Fatigue and Psychological Distress,” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 75 (4) (2002): 259–266. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50. Egan, M., C. Bambra, S. Thomas, M. Petticrew, M. Whitehead, and H. Thomson, “The Psychosocial and Health Effects of Workplace Reorganisation, 1: A Systematic Review Of Organisational-Level Interventions That Aim to Increase Employee Control,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61 (11) (2007): 945–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51. Chandola, T., E. Brunner, and M. Marmot, “Chronic Stress at Work and the Metabolic Syndrome: Prospective Study,” British Medical Journal 332 (7540) (2006): 521–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52. Navarro, V., “Special Report on the Political and Social Contexts of Health, Part I: Introduction: Objectives and Purposes of the Study,” International Journal of Health Services 33 (3) (2003): 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53. US Census Bureau, “Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2008,” tables 6, 7, and 9, available at http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/voting/cps2008.html, accessed December 22, 2009.

- 54. The “civilian labor force” includes government workers, private industry workers, and self-employed workers, as well as the unemployed who are looking for work (and thus technically still in the labor force). Thus, the voting rate of the unemployed is factored into the “employed” voting rate and reduces it.

- 55.Council of Economic Advisers, “Preparing the Workers of Today for the Jobs of Tomorrow.” As the report notes on p. 21, “Without a very careful design, accountability systems that focus on outcomes can have the unintended consequence of encouraging providers to “cream skim,” meaning that they try to enroll only those individuals who are the most likely to land in good jobs or succeed educationally even without assistance.”

- 56.Conway et al., Systems Change.

- 57. Bennett, M. I. J., and R. P. Giloth, “Social Equity and Twenty-First Century Cities,” in: Economic Development in American Cities: The Pursuit of an Equity Agenda, ed. M. I. J. Bennett and R. P. Giloth (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007), 213–235.

- 58.Geronimus et al., “ ‘Weathering’ and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores.” [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59. Bennett and Giloth, “Social Equity and Twenty-First Century Cities,” 220.

- 60. Houghton, T., and T. Proscio, Hard Work on Soft Skills: Creating a “Culture Of Work” in Workforce Development (Philadelphia: Public/Private Ventures, 2001)

- 61. Ibid.