Abstract

Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are G-coupled receptors that modulate synaptic activity. Previous studies have shown that Group I mGluRs are present in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), in which many visceral afferents terminate. Microinjection of selective Group I mGluR agonists into the NTS results in a depressor response and decrease in sympathetic nerve activity. There is, however, little evidence detailing which phenotypes of neurons within the NTS express Group I mGluRs. In brainstem slices, we performed immunohistochemical localization of Group I mGluRs and either glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 kDa isoform (GAD67), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). Fluoro-Gold (FG, 2%; 15 nl) was microinjected in the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) of the rat to retrogradely label NTS neurons that project to CVLM. Group I mGluRs were distributed throughout the rostral-caudal extent of the NTS and were found within most NTS subregions. The relative percentages of Group I mGluR expressing neurons colabeled with the different markers were FG (6.9±0.7) nNOS (5.6±0.9), TH (3.9±1.0), and GAD67 (3.1±1.4). The percentage of FG containing cells colabeled with Group I mGluR (13.6±2.0) was greater than the percent colabeled with GAD67 (3.1±0.5), nNOS (4.7±0.5), and TH (0.1±0.08). Cells triple labeled for FG, nNOS, and Group I mGluRs were identified in the NTS. Thus, these data provide an anatomical substrate by which Group I mGluRs could modulate activity of CVLM projecting neurons in the NTS.

Keywords: nitric oxide, tyrosine hydroxylase, GAD67, Fluoro-Gold, caudal ventrolateral medulla, immunohistochemistry

The nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), located in the dorsal medulla, is the site of the first synapse of cardiovascular, respiratory, and visceral afferent terminals (Chan et al., 2000; Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Spyer, 1990). This includes arterial baroreceptor afferents, which are critical for control of arterial blood pressure on a beat to beat basis (Loewy, 1990). The NTS is a highly integrative nucleus, and baroreceptor input is believed to undergo substantial modulation within the NTS. Output neurons from the NTS then relay this information to the caudal ventrolateral medulla (CVLM) through an excitatory projection. Neurons within the CVLM in turn inhibit spinally projecting pre-sympathetic neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (Andresen and Kunze, 1994; Dampney, 1994; Chan et al., 2000; Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Guyenet, 2006; Loewy, 1990; Aicher et al., 2000). Thus, the activity of NTS neurons projecting to the CVLM is a critical determinant of NTS influence on autonomic function.

Within the NTS, baroreceptor afferent terminals are believed to release the excitatory amino acid glutamate (Talman et al., 1980). Fast-acting ionotropic glutamate receptors within the NTS are required for normal baroreflex function (Andresen and Kunze, 1994; Gordon and Sved, 2002; Talman et al., 1980). Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) also are present in the NTS (Hoang and Hay, 2001; Chen et al., 2002; Hay et al., 1999) and may influence cardiovascular regulation (Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Viard and Sapru, 2002; Chen et al., 2002; Sekizawa and Bonham, 2006; Liu et al., 1998). Blockade of the sympathoinhibition and depressor response due to microinjection of glutamate into the NTS requires antagonism of both ionotropic glutamate receptors and mGluRs (Pawloski-Dahm and Gordon, 1992; Foley et al., 1998, 1999). NTS microinjection of a broad spectrum mGluR agonist or a Group I selective agonist produces a depressor and sympathoinhibitory response (Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Viard and Sapru, 2002). While these effects could be due to activation of several autonomic circuits, they are consistent with activation of baroreflex output neurons to the CVLM. It is currently unknown whether CVLM projecting output neurons from the NTS express Group I mGluRs.

The NTS contains a wide variety of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that influence cardiovascular regulation (Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Aicher, 2001; Lawrence and Jarrott, 1996; Gordon and Sved, 2002). Group I mGluRs could thus affect cardiovascular function by modulating their activity. However, the specific neuronal subtypes in the NTS that are influenced by Group I mGluRs are unknown. GABAergic neurons are located throughout the NTS (Stornetta and Guyenet, 1999; Weston et al., 2003; Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Fong et al., 2005). In addition, previous studies have shown the presence of neurons within the NTS containing neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) (Lin et al., 1998, 2000; Talman et al., 2001; Lin and Talman, 2006; Kantzides and Badoer, 2005) or tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (Kalia et al., 1985a,b; Chan et al., 2000; Bailey et al., 2006), synthetic enzymes for nitric oxide (NO) and catecholamines, respectively. Furthermore, NTS neurons containing nNOS, glutamic acid decarboxylase isoform 67 (GAD67) (a GABA synthesizing enzyme), and TH all are activated by changes in arterial pressure, likely due to changes in baroreceptor activity (Chan and Sawchenko, 1998; Chan et al., 2000; Weston et al., 2003; Minson et al., 1997). Therefore GABA, NO, and TH containing neurons within the NTS all have the potential to influence arterial pressure, sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), and baroreflex function. There is, however, little evidence delineating which cell phenotypes within the NTS express Group I mGluRs.

The overall goal of this study was to examine the expression of Group I mGluRs on specific neuronal subtypes within the NTS. The expression of Group I mGluRs on CVLM projecting output neurons from the NTS was examined using the retrograde tracer Fluoro-Gold (FG). In addition, we evaluated the expression of Group I mGluRs on specific neurochemical phenotypes using immunohistochemistry for synthetic enzymes for GABA, NO and catecholamines in the NTS. Lastly, we examined the neurochemical phenotypes of the CVLM projecting neurons that express Group I mGluRs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Experiments were performed according to the guidelines in the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” The University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures and protocols. Experiments were designed to use the fewest animals required to obtain statistical significance. Proper anesthesia and post-operative care were provided to limit animal discomfort. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) weighing 275–325 g were used (n=14). Rats were housed within an in-house animal facility on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. All rats were given at least 7 days to acclimate to the surroundings prior to any experimental procedure.

Surgical and microinjection procedures

All recovery surgeries were performed under aseptic conditions. Rats were anesthetized with Isoflurane (AErane, Baxter, Deer-field, IL, USA [5% in 100% O2, 2 l per minute for induction; maintenance at 2–2.5%]). A catheter (PE10 fused to PE50) was inserted into the aorta via the femoral artery, and connected to a pressure transducer. Arterial pressure was measured using a DC amplifier (ADInstruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) and heart rate (HR) were determined using a PowerLab Data Acquisition System (ADInstruments) connected to a Pentium computer. The rat was placed in a Kopf stereotaxic device (Tujunga, CA, USA), and the dorsal surface of the medulla was exposed via a limited occipital craniotomy. Calamus scriptorius (CS), defined as the caudal pole of the area postrema (AP), was visualized, and the head of the rat was deflected downward until CS was 2.4 mm posterior to the interaural zero line. This positioned the medulla in the horizontal plane (Moffitt et al., 2002; Kiely and Gordon, 1994). After determining stereotaxic coordinates for CS, a glass pipette filled with appropriate solutions was positioned within the brainstem for microinjection of FG or for functional verification of the CVLM.

FG microinjections

Once stereotaxic coordinates for CS were determined, a double-barreled pipette (OD 20–30 μm) with one barrel filled with L-glutamate (Glu, 10 mM) and the second filled with FG (2% in dH2O) was placed at the initial target stereotaxic coordinates for the CVLM. With the medulla positioned horizontally and CS positioned as described above, these coordinates were 0.2 mm caudal to and 2.0–2.2 mm lateral from CS, and 2.0–2.6 mm ventral to the dorsal surface of the brain. The location of the CVLM was confirmed functionally by responses to microinjection of Glu (30 nl). Criteria for identification of the CVLM were set at a depressor response of ~20 mm Hg with a moderate (~40 beat per minute) decrease in HR. These criteria were met within two to five microinjections of Glu. Once the CVLM was localized, FG (15 nl) was injected at the same CVLM site through the second barrel of the pipette. Microinjections were made using a custom built pressure injection system. Fluid in the pipette was visualized through a 150× microscope (Rolyn Optics, Corvina, CA, USA) with a calibrated eyepiece micrometer, which allowed quantification of the volume injected by measuring the movement of the meniscus within the pipette.

Following the FG microinjection the pipette remained in the medullary tissue for an additional 5 min to minimize movement of FG up the injection tract. After removal of the pipette, the arterial catheter was removed and the leg and neck areas were sutured closed. Animals were given post-operative injections of penicillin-G (Hanford, Syracuse, NY, USA; 0.2 ml i.m.) and Buprenex (Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Richmond, VA, USA; 0.6 mg/ml, i.m.) to prevent infection and for pain management, respectively, and returned to their cages.

Transcardial perfusion and tissue preparation

Five days after FG microinjection, rats were deeply anesthetized with an injection of 0.2 ml Sleepaway (Ft. Dodge, IA, USA) and transcardially perfused with 100–125 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) followed by 450–500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma). Brains were additionally post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 2 h, and stored in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Brains were then blocked approximately at the level of Bregma −7 mm, stripped of the dura, and embedded into 2% agar gel. Thirty micron sections were cut on a vibrating microtome (Vibratome, St Louis, MO, USA), separated into a one in six series and then stored in 0.1 M PBS. One set of sections was mounted on gel-coated slides, air-dried, covered in non-hard set Vectashield (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA), and the coverslip sealed with clear nail polish. This set of sections was used to determine the center of the FG injection and to determine boundaries of the NTS. If immunohistochemistry was performed within 1 week, sections were stored at 4 °C in 0.1 M PBS. All other sections were stored in cryoprotectant at −20 °C.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were treated with a modified immunohistochemical protocol (Fong et al., 2005) to visualize Group I mGluR, GAD67, TH, and nNOS containing cells. The specific steps of the protocol depended on the protein visualized (see below). Preliminary experiments were performed with varying concentrations of primary and secondary antibodies to optimize concentrations that provided the best positive signal with the least background signal. Each immunohistochemical protocol was a pairing of primary antibodies for Group I mGluRs and either GAD67, nNOS or TH. In addition, FG, which autofluoresces, was present in all series treated. All incubations in the immunohistochemical protocols were performed at room temperature on a shaker in sterile 48 well plates (Vector).

Group I mGluRs and GAD67

Sections were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min then rinsed in 0.1 M PBS for 15 min followed by incubation in pre-blocking solution (10% normal goat serum [NGS, Jackson, West Grove, PA, USA] in 0.1 M PBS) for 30 min. Sections were rinsed again for 15 min in 0.1 M PBS, then incubated for 2 days in a cocktail of rabbit anti-mGluR5 (1:500, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) and mouse anti-GAD67 (1:3000, Chemicon) with 3% NGS in 0.1 M PBS at room temperature on a shaker. After the 2 days, sections were rinsed in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min before incubation for 2 h in a cocktail of goat anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:300, Jackson) and goat anti-mouse biotinylated IgG (1:200, Vector) in 3% NGS in 0.1 M PBS. Sections were rinsed in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min, and placed into streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (1:200, PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, USA) with 3% NGS in 0.1 M PBS for 60 min. Sections were rinsed for 30 min, then incubated with TSA-biotin (1:100, PerkinElmer) with 3% NGS in 0.1 M PBS for 15 min. Sections were rinsed for 30 min, then incubated with neutravidin/avidin Oregon Green (1:300, Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 3% NGS in 0.1 M PBS for 2 h. Sections were rinsed for 30 min, mounted on gel-coated slides, air-dried, coverslipped with Vectashield (Vector), and sealed with clear nail polish. Immunohistochemistry involving GAD67 was always performed within 1 week of perfusion of the tissue.

Group I mGluRs and nNOS or TH

Sections were rinsed for 15 min in 0.1 M PBS, followed by a 10% pre-blocking solution (10% normal donkey serum [NDS, Jackson] in 0.1 M PBS) for 30 min. Sections were rinsed again for 15 min in 0.1 M PBS, then incubated for 48 h in a cocktail of rabbit anti-mGluR5 (1:500, Chemicon) and either mouse anti-nNOS (1: 2000, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or mouse anti-TH (1: 500, Chemicon) with 3% NDS in 0.1 M PBS. After primary incubation, the sections were rinsed in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min. Sections were then incubated with a cocktail of donkey anti-rabbit Cy3 (1:300 Jackson) and donkey anti-mouse Cy2 (1:200, Jackson) with 3% NDS in 0.1 M PBS for 2 h. Sections were rinsed in 0.1 M PBS for 30 min. Sections then were mounted onto gel-coated slides, dried, coverslipped with Prolong Gold (Molecular Probes) and sealed with clear nail polish.

Negative controls and antibody specificity

For each immunohistochemical protocol, primary antibodies were withheld on some sections, to serve as non-immune controls. Control sections were examined to verify lack of specific positive labeling.

Specificity of the rabbit anti-nNOS antibody was verified in an immunoblot by the vendor, and the mouse anti-GAD67 antibody was verified by immunoblot in a previous publication (Fong et al., 2005). The rabbit anti-mGluR5 antibody was shown by the vendor to be specific in HEK cells and in a neuronal microsomal preparation. We tested the specificity of the rabbit anti-mGluR5 antibody in brain tissue using two methods. A blocking peptide was synthesized which matched the amino acid sequence against which the antibody was raised. The blocking peptide (1 mg/ml) was pre-incubated with the rabbit anti-mGluR5 antibody for 1 h prior to the inclusion of brain sections. Additional sections were incubated in the rabbit anti-mGluR5 antibody alone (1:500) or in a non-primary control. Sections were incubated for 48 h, and then treated with a fluorescent secondary antibody (see above). In addition, as described below, rabbit anti-mGluR 5 antibody specificity was also verified by immunoblot analysis. The anti-TH antibody was also verified by immunoblot analysis.

Western blot analysis

Rats were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane, decapitated and the brainstem, cerebellum and cortex were rapidly removed. Tissue was suspended and cells lysed by mechanical disruption in two volumes of homogenization buffer (2% Nonidet P-40 in T-PER, Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) freshly added. Following removal of insoluble protein by centrifugation at 14,000×g the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration of the brainstem, cortex and cerebellum was measured by the BCA method (Pierce Chemical Co.). Equal amounts of protein (25 μg) were separated on 4–20% polyacrylamide SDS gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS-0.1% Tween-20 (PBS-T, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) for 2 h at room temperature and incubated with primary antibodies mAb TH (1:1000, Chemicon, cat. #MAB318) or pAb group 1 mGluR (mGluR5, 0.3 μg/mL, Chemicon, cat. #AB5675). After washing, the blots were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit HRP-linked secondary antibodies (1:5000, Santa Cruz and GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK, respectively) in blocking buffer. Following wash, the blots were developed using the Immun-Star WesternC Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the images captured on Hyperfilm-ECL (GE Life Sciences).

Microscopy and image analysis

After the immunohistochemical procedure, sections were examined using an Olympus microscope (BX51), equipped with a three-axis motorized stage (Ludl Electronic Products Ltd., Hawthorne, NY, USA) and with filter sets for Oregon Green 488 or Cy2 [ex. λ480 nm; em. λ510 nm], Cy3 [ex. λ550 nm; em. λ570 nm], and FG [ex. λ330 nm; em. λ515 nm]. Images were captured using a cooled monochrome digital camera (ORCA-AG, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Image analyses and cell localization were performed using the software package Neurolucida (version 7.5, MicroBrightField, Williston, VT, USA).

For each immunohistochemical group examined, CS was defined as the section in which the caudal pole of the AP is present. Sections from 360 μm caudal to 1260 μm rostral to CS were counted. Sections were outlined and the injection site of FG in the CVLM was verified. The NTS, tractus solitarius, and adjacent nuclei ipsilateral to the FG injection site were outlined. The top and bottom of the section in the Z-axis were defined and a stacked image of photomicrographs was taken, with a distance of 1 μm between each image, representing the full thickness of the section. Three stacks of images were taken, one for each filter set without altering the position of any of the three axes. Positively immunoreactive (IR) and FG containing cells in the NTS were counted. The following criteria were set for counting cells: GAD67, TH, and nNOS-IR cells exhibited complete cytosolic labeling with a blank nuclear region. FG containing cells had either punctate labeling or completely filled cells in which no nuclear region was visible. mGluR-IR cells exhibited labeling that surrounded the soma. Cells with labeling that did not meet these criteria were not counted. When positive signals that fit the criteria above were observed under different filter sets, and these occurred in the same focal plane with similar cell morphology, the cells were considered double-labeled. Cells that contained positive signal with all three filter sets were considered triple-labeled.

Data analysis

After completion of analysis of each brain, the data were exported to the software package NeuroExplorer (version 4.5, MicroBrightField), separated into single-, double- and triple-labeled cells in each specific outlined section (see above), and exported into a spreadsheet (Excel 11.656, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). The data were expressed in individual sections based on distance from CS. In addition, total counts, counts in sections caudal to the AP (caudal NTS; ~Bregma −15.24 to −14.4 mm), at the level of AP (postremal NTS; ~Bregma −14.4 to −13.56) and rostral to AP (rostral NTS; ~Bregma −13.56 to −12.96) were evaluated. Furthermore, the percentage of double-labeled cells relative to the number of each of the single-labeled cells was determined. Calculation of the percent of colabeling was achieved by dividing the number of colabeled cells by the total number of each of the single-labeled cells. In this manner, the extent of colabeling was expressed as a percent of the total number of cells with each individual label. The total number of triple-labeled cells of each immunohistochemical grouping was used to determine the percent of double-labeled cells that were also triple labeled. Graphs of data were generated using SigmaPlot (8.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Distribution of cells was determined by examination of sections in NeuroExplorer. Locations of various subnuclear regions were determined using a standard brainstem atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007).

For representative digital images of individual and co-labeled neurons, single images were taken with each appropriate filter of selected sections. These images were acquired with NeuroLucida (MicroBrightField) and then imported, pseudocolored, and merged using Photoshop (version 7.0, Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). Only brightness and contrast were adjusted for clarity.

Functional verification of CVLM

Experiments were performed to further verify that the functional criteria used for our FG microinjections were within the cardiovascular regions of the CVLM which receive input from a depressor region of the NTS (Aicher et al., 2000). A separate group (n=4) of Sprague–Dawley rats was anesthetized with isoflurane (AErane, Baxter [5% in 100% O2, 2 l per minute; maintenance at 2–2.5%]). Rats were instrumented as above. A tracheotomy was performed, rats were ventilated and a catheter (PE10 fused to PE50) was inserted into the inferior vena cava via the femoral vein. Once the dorsal medullary area was visualized, rats were gradually removed from isoflurane while receiving bolus injections (0.05 ml) of Inactin (100 mg/ml, i.v for a total dose of 100 mg/kg over ~30 min). Microinjections were performed using a triple-barreled pipette (OD 30–40 μm), containing Glu (10 mM), the general ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid (KYN, 40 mM), and 2% Chicago Sky Blue dye (Sigma). Once the CVLM was located by a depressor response to Glu (30 nl) as described above the pipette was moved to the region of the NTS (0.5 mm rostral and 0.5 mm lateral to CS, and 0.5–0.7 mm ventral from the dorsal surface). Glu (30 nl) was microinjected to verify the region of the NTS producing a depressor response. Appropriate pipette placement was verified by a 15–20 mm Hg reduction in MAP in response to Glu. The pipette was returned to the CVLM and a depressor response was reconfirmed with an additional application of Glu. KYN (40 mM, 15 nl) was then microinjected into the CVLM to block ionotropic glutamate receptors. The pipette was then returned to the coordinates of the NTS, and Glu microinjected as before. Glu injections were repeated every 5 min until the depressor response recovered. After completion of the experiment, NTS and CVLM microinjection sites were each labeled with 15 nl of 2% Chicago Sky Blue dye. Animals were killed with 0.2 ml Sleepaway i.v. Brains were removed and placed into formalin for subsequent histological analysis.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean±S.E. Hemodynamic responses to Glu microinjection into the CVLM were analyzed by a Student's t-test. Absolute values of MAP and HR in response to Glu microinjection into the NTS under control conditions, after KYN injection and during recovery were analyzed by repeated measures (RM) two-way ANOVA. The change in MAP and HR due to Glu microinjection into the NTS before, during, and after KYN injection, the regional distribution of counted labels and the percent of colabeling were analyzed with one-way RM ANOVA. The rostral–caudal distribution of Group I mGluRs and FG in the different immunohistochemical protocols was compared by two-way RM ANOVA. When appropriate, ANOVAs were followed by a Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat software and significance was accepted at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Validation of immunohistochemical and FG protocols

Specificity of the Group I mGluR antibody and the TH antibody is demonstrated in Fig. 1. A photomicrograph of positive labeling for Group I mGluRs (Fig. 1A1) was taken, and without changing exposure time, photomicrographs of the nonimmune control (Fig. 1A3) and the blocking peptide (Fig. 1A4) were taken. Pre-incubation of the blocking peptide with the Group I mGluR antibody resulted in no staining (Fig. 1A4), similar to that seen in the non-immune control (Fig. 1A3). Fig. 1A2 is the enlarged cell denoted by the arrow in Fig. 1A1. Immunoblots for Group I mGluRs in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum and for TH in brainstem (Fig. 1B) show single bands at the appropriate molecular weights.

Fig. 1.

Specificity of mGluR and TH antibodies. (A) Photomicrographs of positive labeling for mGluR 5 antibody (A1), nonimmune control (A3), and in the presence of blocking peptide (A4). A2 is a higher magnification of the cell indicated by the white arrow in A.1. (B) Immunoblots for mGluR 5 in the cerebral cortex (CTX) and cerebellum (CB) show a single band at molecular weight ~132 kDa. Immunoblot for TH in the brainstem (BS) shows a single band at molecular weight ~60 kDa.

Representative photomicrographs within the NTS of each neurochemical phenotype evaluated are shown in Fig. 2. Photomicrographs of sections treated with antibodies were taken (Fig. 2A1–D1), and without changing camera exposure time, images of non-primary control sections were taken (Fig. 2A2–D2). No positively labeled cells were observed in the absence of the primary antibody.

Fig. 2.

Validation of immunohistochemical protocols. Epifluorescent photomicrographs of immunopositive labeling for Group I mGluRs (A1), GAD67 (B1), nNOS (C1) and TH (D1). Controls (omission of primary antibody) are shown in A2–D2. Both positive and control images were taken from regions of the NTS that were examined in this study. Arrows in A–D denote positively labeled neurons. Control images were taken at the same exposure time as their positively labeled counterparts in adjacent sections and did not show any positive immunohistochemical label. Scale bar=25 μm.

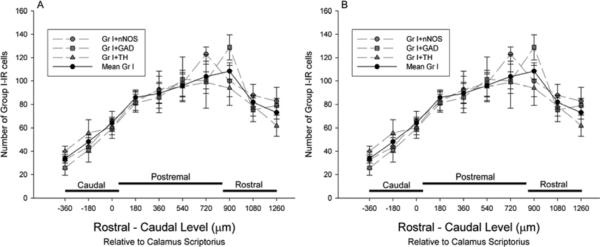

Group I mGluRs and FG were included in each of the immunohistochemical protocols. To verify that inclusion of different antibodies, immunohistochemical protocols and cryoprotection did not affect the labeling of Group I mGluRs or FG, we compared the amount and distribution of Group I and FG labeling among the different protocols. There were no significant differences in the number or distribution of Group I mGluRs (Fig. 3A) or FG labeled cells (Fig. 3B) among any of the protocols. Mean values for the three protocols are represented by the solid lines.

Fig. 3.

Rostral–caudal distribution of Group I mGluRs and FG. (A) Distribution of Group I mGluR IR cells and (B) FG containing neurons from separate protocols for immunohistochemical visualization of Group I mGluRs paired with GAD67, nNOS, or TH (n=5 each). The thick line depicts the mean of the three protocols for Group I mGluRs and FG.

Distribution of immunolabeling within the NTS

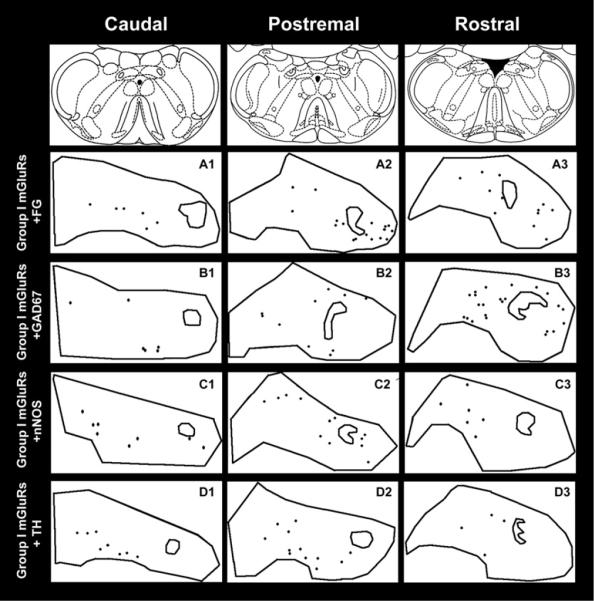

Cells that were IR for each marker were observed throughout the rostral– caudal distribution of the NTS. Fig. 4 is a diagrammatical illustration showing the distribution of positive labeling for each marker at three rostral–caudal levels of the NTS in individual animals. Table 1 details the average number of positively labeled neurons per section within the three regions of the NTS examined. The description of positive labeling within the three regions of the NTS follows.

Fig. 4.

Anatomical location of positive immunolabeling and CVLM projecting neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS). Representative diagrammatic images from the NTS of Group I mGluRs (A), FG (B), GAD67 (C), nNOS (D), and TH (E) labeling. Each point represents a labeled cell. (A1–E1) Representative sections of the NTS caudal to CS. (A2–E2) Representative sections from the postremal NTS, at the level of the AP. (A3–E3) Representative sections from the rostral NTS, through 540 μm rostral to the rostral margin of AP.

Table 1.

Regional distribution of immunoreactive or CVLM retrogradely labeled cells in the NTS

| Region | Gr I mGluR | FG | GAD67 | nNOS | TH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caudal NTS | 45.9±3.6* | 29.2±4.2* | 30.7±2.5* | 15.8±2.8* | 16.9±1.7 |

| Postremal NTS | 90.5±5.4 | 57.7±8.6 | 65.1 ±7.5 | 49.3±4.3+ | 34.1 ±4.2 |

| Rostral NTS | 91.3±6.1§ | 48.8±9.8§ | 82.1±9.1§ | 76.5±8.1§ | 26.5±5.1 |

Average number of positively labeled cells per section at each rostral-caudal level in the NTS for each phenotype: Group I mGluRs (Gr I mGluR), FG, GAD67, nNOS and TH. Numbers are mean±S.E. A total of 743±38 Group I mGluR, 434±62 FG, 558±43 GAD67, 441±41 nNOS, and 261±19 TH labeled neurons was analyzed.

P<0.05 caudal NTS vs. postremal NTS.

P<0.05 postremal NTS vs. rostral NTS.

P<0.05 rostral NTS vs. caudal NTS.

Group I mGluRs

Group I mGluRs exhibited primarily punctate labeling that surrounded a large dark region, suggestive of labeling associated with the plasma membrane (Figs. 2A1, 5A1–C1). Additional punctate labeling was exhibited throughout the NTS consistent with terminal labeling. Group I mGluRs were distributed extensively throughout the rostral–caudal axis of the NTS (Figs. 3A; 4A1–A3). The number per section of Group I mGluR-IR cells in the postremal and rostral regions of the NTS was significantly greater than in the caudal region (Table 1). Sub-nuclear distribution within the NTS was estimated by comparison to a standard anatomical atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). Within the caudal NTS (Fig. 4A1), the Group I mGluR-IR cells were observed in the medial subnucleus, with some cells expressing Group I mGluRs in surrounding subnuclei. Group I mGluR-IR cells were located throughout the postremal region of the NTS (Fig. 4A2), with dense expression in the medial, intermediate, ventral, and ventrolateral subnuclei. The central subnucleus showed dense labeling in the rostral sections of the postremal NTS region. In the rostral NTS (Fig. 4A3), Group I mGluR-IR cells were present diffusely throughout the region, although a dense cluster was found in the medial subregion.

Fig. 5.

Colabeling of Group I mGluRs with specific neuronal types. Representative pseudocolored photomicrographs of Group I mGluRs immunoreactivity (–IR, A1, B1, C1), labeling of FG (A2), nNOS-IR (B2) and TH-IR (C2). Merged images are shown in A3–C3. Cells that are colabeled are depicted by white arrows. Representative images were taken of cells dorsolateral to solitary tract (A, B) or in the medial subnucleus of the NTS (C). Scale bar=25 μm. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.

Retrogradely labeled CVLM projecting cells

Microinjection of FG into the CVLM resulted in neuronal labeling at all rostral–caudal levels of the NTS, primarily ipsilateral to the FG injection (Figs. 3B; 4B1–B3). All animals displayed a similar qualitative FG distribution in the NTS, for all the CVLM injection sites used in this study. Somal FG labeling was either punctate [presumed FG filled lysosomes; (Wessondorf, 1991)] or appeared as completely filled cells. Some labeled soma also exhibited processes that were labeled (Figs. 5A2; 8A1–C1). Similar to Group I mGluR-IR, the number per section of FG-labeled cells in the postremal and rostral NTS was significantly greater than in the caudal NTS (Table 1). Within the caudal region of the NTS (Fig. 4B1), labeling was observed primarily in the medial sub-region, with some labeling in the dorsolateral, ventral, and ventrolateral subnuclei. In the postremal region of NTS (Fig. 4B2), the greatest amount of FG labeling was observed in areas that surrounded the solitary tract, including the lateral, ventrolateral, interstitial, intermediate, and posterior subnuclei. There was also a strip of labeling in the dorsolateral subnucleus. In the rostral NTS (Fig. 4B3), FG containing cells exhibited heavy labeling in the lateral and ventrolateral subnuclei, with less labeling in the intermediate and interstitial subnuclei.

Fig. 8.

Colabeling of FG with other neuronal phenotypes. Pseudocolored photomicrographs of FG alone (A1–C3), GAD67 (A2), nNOS (B2), TH (C2) and merged images of FG with each label (A3–C3). Cells that are colabeled are indicated by the white arrows. Images were taken from the NTS, from areas surrounding the solitary tract. No colabeling was seen in the majority of FG and TH containing neurons. Scale bar=25 μm. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.

GAD67 cells

GAD67-IR cells exhibited staining with an unlabeled nuclear region, suggesting the labeling was cytosolic (Figs. 2B and 8A2). Also, punctate labeling was located throughout the NTS, consistent with presynaptic terminal labeling. There was a significantly greater number of positively labeled GAD67 neurons in the postremal and rostral regions compared with the caudal region (Table 1). However, within each level, GAD67-IR cells were heterogeneously distributed throughout the NTS (Fig. 4C1–C3).

nNOS cells

nNOS containing cells exhibited cytosolic labeling with a dark, unstained nuclear region (Figs. 2C, 5B2, 8B2). Most cells showed labeling in at least one process. Labeling on individual fibers was also visible. The number of nNOS-IR cells (Fig. 4D1–D3) was significantly greater in the postremal and rostral regions than the caudal regions of the NTS, and there was significantly more labeling in rostral NTS than the postremal NTS (Table 1). Within the caudal NTS (Fig. 4D1), nNOS-IR cells were found in the medial and dorsolateral subnuclei, with less labeling lateral to the solitary tract. In the postremal region of the NTS (Fig. 4D2), nNOS-IR cells were located in the gelatinous, medial, and dorsolateral subnuclei, with some labeling in the lateral subnuclei. In the rostral NTS region (Fig. 4D3), labeling was localized to the medial and central subnuclei.

TH cells

TH-IR cells were large, brightly labeled cells, with cytosolic labeling (Figs. 2D, 5C2, 8C2). Each cell exhibited labeling in at least one process, with some TH-IR cells having multiple labeled processes. Labeling on fibers surrounding the soma was also observed (Fig. 8C2). The average number of TH-IR cells per section was not different among the different NTS regions (Table 1). The overall distribution of TH-IR cells was discrete, with positive labeling found in specific subnuclei (Fig. 4E1–E3). In the caudal NTS, TH positive cells were localized primarily to the medial and commissural subnuclei (Fig. 4E1). In the postremal NTS region, groups of labeled cells were located in the medial and dorsolateral subnuclei (Fig. 4E2). In the rostral NTS region the distribution of positively labeled TH cells was localized primarily in the medial subnucleus and the medial edge of the NTS along the floor of the fourth ventricle (Fig. 4E3).

Colabeling of Group I mGluR expressing cells within the NTS

The colabeling of Group I mGluRs with each of the other cell types was examined. Representative pseudocolored photomicrographs of Group I mGluR immunoreactivity on CVLM projecting, nNOS or TH containing cells within the NTS are shown in Fig. 5. The number of dual-labeled cells of each type as a percent of the number of Group I mGluR-IR cells is shown in Fig. 6A. The percentage of Group I mGluR-IR cells that contained FG was greater than the percent of cells colabeled with GAD67 or TH. However, the percent of Group I mGluR-IR cells containing FG or nNOS was similar. Fig. 6B presents the number of dual-labeled cells as a percent of the number of cells of each individual specific subtype. There were no significant differences among the specific cell types in colabeling with Group I mGluR-IR cells, although there was a trend (P=0.07) for the percent of FG, nNOS, and TH containing cells that also express Group I mGluRs to be higher than the percent of GAD67-IR cells with Group I mGluR-IR. Representative examples of distribution of each colabeled pair in individual animals are displayed in Fig. 7. Colabeling was not specific to particular subregions and occurred throughout regions containing single labels in the NTS.

Fig. 6.

Percent co-labeling of Group I mGluR positive cells in the NTS. Group I mGluR-IR cells co-labeled with FG, GAD67, nNOS, or TH, expressed as (A) a percentage of the number of Group I mGluR-IR cells; (B) a percentage of the specific subtype of labeled cells. Bars are mean±S.E. * P<0.05 vs. FG.

Fig. 7.

Anatomical location of Group I mGluR colabeled cells in the NTS. Representative diagrammatic images of Group I mGluR colabeled neurons. Images depict Group I mGluRs and FG (A), GAD67-IR (B), nNOS-IR (C), and TH-IR (D). Each point represents a dual-labeled cell. (A1–D1) Representative sections of the NTS caudal to CS. (A2–D2) Representative sections from the postremal NTS. (A3–D3) Representative sections from the rostral NTS. Colabeling occurred at all rostral–caudal levels of the NTS and was not restricted to any particular subregions.

Colabeling of CVLM projecting cells

Colabeling of FG containing cells with GAD67, nNOS, and TH was also examined. Representative pseudocolored photomicrographs of colabeled cells within the NTS are shown in Fig. 8. The relative amount of colabeling was determined as a percent of both the number of CVLM projection cells (containing FG) and of individual specific cell types, in the same fashion as Group I mGluRs (see above). A greater proportion of CVLM projecting cells (Fig. 9A) colabeled for Group I mGluRs compared with GAD67, nNOS, and TH colabeling. Relative to the number of cells of specific subtypes (Fig. 9B), the percentage of GAD67-IR cells that project to CVLM (FG) was significantly less than the percent of Group I mGluR-IR cells with FG. The percent of nNOS-IR cells that contained FG was not significantly different from the percent of Group I mGluR-IR cells colabeled with FG. Though colabeling of FG and nNOS was relatively low, these two types were distributed in the same subnuclei, and in some cases, in close proximity. There was very little colabeling of FG and TH within the NTS (three colabeled cells of ~270 total TH-labeled cells) and the percent of colabeling was significantly less than that of Group I mGluRs or nNOS with FG.

Fig. 9.

Percent co-labeling of CVLM-projecting cells in the NTS. FG cells colabeled with Group I mGluRs, GAD67, nNOS, or TH, expressed as (A) a percentage of the number of FG cells; (B) a percentage of the specific subtype of labeled cells. Bars are mean±S.E. * P<0.05 vs. Group I mGluRs; + P<0.05 vs. nNOS.

Triple-labeling of Group I mGluR and different neurochemical phenotypes of CVLM projecting cells

Although few, we did observe some triple-labeled cells. No TH-IR cells were labeled for both Group I mGluRs and FG. Typically, there were four to five GAD67-IR cells per animal that expressed Group I mGluRs and also projected to the CVLM. This constituted ~20% of the GAD67-IR neurons that expressed Group I mGluRs, ~30% of GAD67-IR cells that projected to the CVLM, and ~10% of CVLM projecting neurons that expressed Group I mGluRs. The total number of triple-labeled GAD67 neurons was less than 1% of each of the respective single-labeled cells.

There were 10–15 nNOS containing cells per animal that expressed Group I mGluRs and also projected to the CVLM. This constituted ~25% of the nNOS neurons that expressed Group I mGluRs and ~17% of CVLM projecting neurons that expressed Group I mGluRs. Interestingly, ~47% of the nNOS-IR neurons that projected to the CVLM also were Group I mGluR-IR. The total number of triple-labeled nNOS neurons was below 2% of each of the respective single-labeled cells.

Functional and histological identification of CVLM injection sites

In all animals that received FG microinjections the CVLM first was functionally identified by cardiovascular responses to Glu (10 mM, 30 nl) injection. Microinjection of glutamate into the CVLM resulted in a depressor response (−21±3 mm Hg) and a decrease in HR (−34±8 bpm). Prior to immunohistochemical protocols, a series of medullary slices from each animal was examined to anatomically define the site of the FG microinjection. Injection sites were found to be 0.54–1.08 mm rostral to CS (Fig. 10A), with the injections centered within the region of the CVLM (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). Fig. 10B is a representative dark field photomicrograph of the FG injection site indicating the center of the injection within the CVLM. Fig. 10C is a pseudocolored photomicrograph depicting the spread of FG around the midpoint of the injection site.

Fig. 10.

Histological verification of CVLM injection sites. (A) Locations of the center of FG microinjections. Black dots represent the midpoint of the FG microinjection site for animals used in this study. (B) Dark field photomicrograph of a representative FG injection site. (C) Pseudocolored photomicrograph of same section in (B) showing FG injection site and labeling in the NTS. Section is located 540 μm rostral to CS. Arrow points to center of injection site. XII: Hypoglossal nucleus. Scale bar=500 μm. For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.

To further assess our CVLM injection sites, additional experiments were performed to ensure that CVLM injections were in a region required for depressor responses to activation of the NTS. This group of animals (n=4) received microinjections of L-Glu (10 mM, 30 nl) into the NTS before, during, and after blockade of ionotropic glutamate receptors in the CVLM with microinjections of KYN (40 mM, 15 nl). Locations for CVLM microinjections were determined by responses to L-Glu as described above. Unilateral microinjection of L-Glu into the NTS significantly reduced MAP and HR (Con, Fig. 11A, 11B). Ipsilateral microinjection of KYN (40 mM, 15 nl) into the CVLM had no significant effect on MAP or HR (data not shown). KYN microinjection into the CVLM did, however, abolish the cardiovascular responses to Glu injection into the NTS (Kyn-CVLM, Fig. 11A, B). Within 20–40 min, the response to microinjection of Glu recovered to pre-KYN microinjection responses (Rec, Fig. 11A, B). Histological analysis of the brainstems indicated that NTS injection sites (Fig. 11C) corresponded with NTS regions known to receive baroreceptor afferent projections (Ciriello, 1983; Loewy, 1990; Spyer, 1990; Andresen and Kunze, 1994). In addition, injection sites for KYN within the CVLM (Fig. 11D) were similar to injection sites for FG in the immunohistochemical experiments.

Fig. 11.

Functional and histological verification of CVLM injection sites. The response to glutamate microinjection into the NTS is blocked by ionotropic glutamate receptor blockade in the region of the CVLM. Change in MAP (A) or HR (B) due to glutamate (10 mM; 30 nl) microinjection into the NTS under control conditions (Con), in the presence of kynurenate (Kyn-CVLM) and following recovery (Rec). Bars are mean±S.E.; * P=0.05. The location of Glu microinjections in the NTS (C) and CVLM (D) of the four animals in this set of experiments.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the distribution of Group I mGluRs in the NTS on four separate neuronal subtypes: CVLM projecting neurons, retrogradely labeled with FG; GABAergic neurons, indicated by immunoreactivity for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67); nitroxidergic neurons, indicated by nNOS; and catecholaminergic neurons, indicated by TH immunoreactivity. The primary findings were that Group I mGluRs are expressed throughout the NTS and are present on a variety of cell types known to influence autonomic nervous system function within the NTS. The percent of CVLM projecting Group I mGluR-IR cells was similar to the percent containing nNOS. A greater proportion of Group I mGluR-IR cells projected to the CVLM compared with the percent that also contained GAD67 or TH. Furthermore, a greater percentage of CVLM projecting NTS cells expressed Group I mGluRs compared with those that contained GAD67, nNOS or TH. Thus, Group I mGluRs in the NTS could influence autonomic function by affecting cells that then project to the CVLM or by modulating the activity of other NTS cells known to influence cardiovascular regulation.

mGluRs

G-protein-coupled mGluRs are located throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Conn and Pin, 1997; Pin et al., 1999; Schoepp, 2001). mGluRs are divided into three different subgroups, based on amino acid sequence homology and signal transduction mechanisms. Group I mGluRs include receptor types 1α and 5, and generally activate phospholipase C. Group II includes receptor types 2 and 3, and are negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase. Group III includes receptor types 4, 6, 7, and 8 and are also negatively coupled to adenylate cyclase. Group I mGluRs are generally found postsynaptically, while group II and group III mGluRs are localized primarily presynaptically (Schoepp, 2001; Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Conn and Pin, 1997; Pin et al., 1999).

mGluRs modulate synaptic transmission within the NTS (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Schoepp, 2001; Andresen and Kunze, 1994; Chen et al., 2002; Jin et al., 2004; Sekizawa and Bonham, 2006; Endoh, 2004; Glaum and Miller, 1992) and activation of Group I mGluRs within the NTS influences autonomic function (Viard and Sapru, 2002; Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Matsumura et al., 1999). Microinjections of non-specific mGluR agonists and Group I mGluR selective agonists result in reductions in MAP, HR and SNA. Thus, activation of Group I mGluRs mimics the response to glutamate microinjection or excitatory amino acid release within the NTS (Viard and Sapru, 2002; Foley et al., 1998, 1999).

Similar to previous studies (Hay et al., 1999), our data indicate that Group I mGluRs are expressed throughout the NTS. The greatest expression was at the level of and rostral to the AP. The presence of a greater expression of Group I mGluRs in the postremal region of the NTS may suggest a more pronounced role for modulating synaptic transmission in this region. Interestingly, postremal NTS is a region from which microinjection of Group I mGluR agonists elicits depressor responses and sympathoinhibition (Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Viard and Sapru, 2002; Matsumura et al., 1999).

Group I mGluRs were also expressed, although at relatively low levels, on each phenotype of neuron that we examined. Among the cell types evaluated, the percentage of colabeling of Group I mGluRs with CVLM projecting (FG) neurons was higher than most other phenotypes. Furthermore, a greater percentage of the CVLM-projecting neurons expressed Group I mGluRs than any of the other markers examined. Most of the evidence indicates that Group I mGluRs increase cell excitability (Schoepp, 2001; Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Conn and Pin, 1997; Pin et al., 1999). Therefore, colabeling of Group I mGluRs with CVLM projecting (FG) neurons is consistent with previous work showing that Group I mGluR agonists microinjected into the NTS reduce MAP and SNA, presumably by activation of the CNS baroreflex pathway (Viard and Sapru, 2002; Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Matsumura et al., 1999). Thus, one mechanism by which stimulation of Group I mGluRs in the NTS could inhibit sympathetic nervous system function is by increased excitation of these CVLM-projecting neurons.

There was a trend for nNOS and TH containing cells in the NTS to exhibit greater Group I mGluR-IR compared with GAD67 containing cells. This is consistent with previous work in which microinjection of NO donors into the NTS decreased MAP and SNA (Talman et al., 1980; Lewis et al., 1991; Ohta et al., 1997). Activation of nNOS containing neurons by Group I mGluRs would likely increase production and release of NO within the NTS, resulting in decreased MAP and SNA. TH neurons in the NTS project to a variety of other brain regions involved in regulation of the autonomic nervous system, including the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Hermes et al., 2006; Kalia et al., 1985a,b), parabrachial nucleus (Hermes et al., 2006), central nucleus of the amygdala (Reyes and Van Bockstaele, 2006), and the nucleus paragigantocellularis (Reyes and Van Bockstaele, 2006). Group I mGluRs could influence autonomic function by modulating the activity of these neurons. Taken together, the data are consistent with the idea that Group I mGluRs are expressed on cells in the NTS that contribute to pathways involved with autonomic regulation.

Group I mGluRs are generally thought to be located postsynaptically (Schoepp, 2001; Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Conn and Pin, 1997; Pin et al., 1999). Within the NTS, studies in vitro suggest that activation of mGluRs produces postsynaptic effects, including depolarization, activation of an inward current, potentiation of ionotropic glutamate receptor evoked currents, inhibition of GABAA receptor mediated currents, and activation of a Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Glaum and Miller, 1992, 1993a,b; Endoh, 2004; Sekizawa and Bonham, 2006). These studies demonstrate that mGluRs can influence NTS cellular activity postsynaptically, likely through Group I receptors. Also, studies utilizing RT-PCR have shown that, compared with the NTS, expression of Group I mGluR mRNA is lower (Chen et al., 2002) or not present (Hoang and Hay, 2001) in nodose ganglia, which contain cell bodies of visceral afferents. In addition, Chen et al. (2002) reported that Group II and Group III mGluRs, but not Group I mGluRs, inhibit glutamate release from the presynaptic terminal of labeled afferent neurons. Taken together, these data are consistent with the concept that Group I mGluRs are located predominantly postsynaptically rather than presynaptically on visceral afferent terminals. Nevertheless, a recent study (Jin et al., 2004) suggested that presynaptic Group I mGluRs in the NTS can regulate the release of GABA or glutamate. In the current study, much of the Group I mGluR labeling appeared to be membrane associated. Although we could not determine with certainty whether this labeling was pre- or postsynaptic, it met our criteria for cellular labeling. There also was heavy punctuate labeling throughout the NTS, which we did not quantify but which was consistent with terminal labeling. Thus, it is possible that both presynaptic and postsynaptic Group I mGluR immunoreactivity was present and the current data are consistent with the presence and effects of Group I mGluRs, both presynaptic and postsynaptic, within the NTS.

CVLM projecting neurons

The NTS serves as the termination point for multiple visceral afferents (Wallach and Loewy, 1980; Ciriello, 1983; Mendelowitz et al., 1992; Andresen and Kunze, 1994), including arterial baroreceptors. Baroreflex-mediated sympathoinhibition and depressor responses then require a projection from the NTS to the CVLM. Baroreceptor afferent input undergoes substantial integration within the NTS. Thus, the phenotype and neuronal influences on NTS neurons projecting to the CVLM are critical to the autonomic effects of NTS activation.

In the current study, microinjections of FG into the CVLM produced a pattern of labeling within the NTS generally similar to what has been reported previously for CVLM projecting NTS neurons (Weston et al., 2003; Hermes et al., 2006; Gordon, 1987). FG labeling was strongest in the medial subregion of the caudal NTS and in subregions surrounding the tractus solitarius in the postremal and rostral NTS. The CVLM is a heterogeneous nuclear region that lacks defined boundaries and is in close proximity with other regions of the ventral medulla that influence cardiorespiratory regulation. Presumably any NTS cells that project to the CVLM, independent of function, would be labeled with FG. Several lines of evidence suggest our FG injections were centered in regions of the CVLM involved with arterial baroreflex function. The range of our injection sites was similar to regions of the CVLM shown to be required for baroreflex control of blood pressure (Schreihofer and Guyenet, 2003; Jeske et al., 1993; Gordon, 1987; Ross et al., 1985; Hermes et al., 2006; Mandel and Schreihofer, 2006) and Glu (30 nl) microinjected into the CVLM produced a depressor response, with only a modest decrease in HR. Importantly, microinjection of small volumes of KYN (15 nl) into the same coordinates of the CVLM as above blocked the depressor response due to Glu microinjection into the NTS. Thus, although we did not directly evaluate their function, our results are consistent with the concept that at least some of our NTS neurons that project to the CVLM likely contribute to arterial baroreflex function.

A small percentage of CVLM projecting NTS neurons appeared to be GABAergic, as indicated by colabeling of FG and GAD67. This is consistent with previous work (Weston et al., 2003) demonstrating a GABAergic projection from NTS to CVLM. However, the level of GAD67 and FG colabeling in our study was lower than previously reported (Weston et al., 2003). The reasons for this discrepancy are not clear, but may be due to differences in experimental approaches. Weston et al. (2003) used in situ hybridization to label GAD67 mRNA, iontophoresis of FG, and an amplification technique to detect FG. In contrast, we examined GAD67 protein using immunohistochemistry, used microinjection to apply the retrograde tracer, and used FG autofluorescence to identify CVLM projecting neurons. Regardless of these differences, in both the previous work (Weston et al., 2003) and the present study, relatively few neurons that project to the CVLM were GABAergic.

As previously shown, nNOS immunoreactivity (Lin et al., 1998, 2000; Talman et al., 2001; Lin and Talman, 2006; Kantzides and Badoer, 2005; Lawrence et al., 1998) was detectable in the NTS. The pattern of distribution of FG and nNOS labeling within the NTS was similar and the two labels were often in close proximity. Given the well-established role of NO as a diffusible neuromodulator (Dias et al., 2005; Paton et al., 2002; Talman, 2006), these results suggest that NO released within the NTS could modulate activity of CVLM projecting neurons. In addition, a small degree of colabeling of FG and nNOS was observed. Thus, NO may also influence activity of the CVLM directly via neurons from the NTS that release NO within the CVLM.

The percentage of colabeling of FG and TH was negligible. In the five sets of NTS tissue that were immunohistochemically processed, we counted only three CVLM projecting neurons that also contained TH. NTS catecholaminergic neurons, contained in the A2 neural group, have been shown to project to a variety of brain regions (Kalia et al., 1985a,b; Hermes et al., 2006; Reyes and Van Bockstaele, 2006), although only a small number appear to project to the CVLM (Hermes et al., 2006). The percentage of FG and TH colabeling in our study was less than that observed by Hermes et al. (2006). This variation may be due to several factors, including the amounts of tracer microinjected into the CVLM. Hermes et al. (2006) utilized 50–80 nl of FG, whereas we injected 15 nl. It is likely that our lower volume FG injections in the CVLM account in part for less colabeling of FG and TH than previously reported (Hermes et al., 2006).

Triple-labeled neurons

We also examined Group I mGluR immunoreactivity on phenotypically different CVLM projecting NTS neurons. There were few triple labeled neurons detected in any of the immunohistochemical groups. There were no triple-labeled Group I mGluR, FG, and TH neurons. This is not surprising, as the number of catecholaminergic NTS neurons that projected to the CVLM was very small. Similarly, there were only a few triple-labeled GAD67 neurons, consistent with the finding that relatively few CVLM-projecting neurons in the NTS were positively labeled for GAD67. Also, because microinjection of Group I mGluR agonists into the NTS results in a depressor response (consistent with activation of CVLM neurons) it is not surprising that a low percentage of CVLM-projecting neurons expressed both Group I mGluRs and GAD67.

Of interest are triple-labeled neurons for Group I mGluRs, nNOS, and FG. Nearly half of nNOS neurons that projected to the CVLM also expressed Group I mGluRs. Furthermore, a fourth of the NTS neurons that expressed Group I mGluRs and were nNOS-IR also projected to the CVLM. Microinjection of Group I mGluR agonists (Foley et al., 1998, 1999; Viard and Sapru, 2002; Matsumura et al., 1999) and NO donors (Talman et al., 1980) into the NTS results in depressor responses and the current data provide an anatomical substrate by which these modulators may interact. For example, Group I mGluRs could decrease arterial pressure in part either by activating nNOS cells that then release NO within the NTS or by activating nNOS neurons that project to CVLM and release NO within the CVLM. Future studies are required to address these possibilities.

Technical considerations

In the present study, we used immunohistochemistry to identify different neurochemical phenotypes. The use of strict criteria for determining positively labeled cells versus nonlabeled or partially labeled cells minimizes the possibility of false positives. This may also lead to underestimation of positively labeled cells. In some cases, the use of multiple sets of tissue from the same animals served as their own controls. Group I mGluRs and FG were counted in each immunohistochemical pairing. The number and distribution of cells positively labeled for Group I mGluRs or FG were similar among the different immunohistochemical protocols, providing evidence of the reproducibility of our results.

The antibody that was used to detect Group I mGluRs recognizes both Group I subtypes, mGluR 1α and mGluR 5. It has been suggested that mGluR 5 can be located both presynaptically and postsynaptically, whereas mGluR 1α is found primarily postsynaptically. According to the criteria used, NTS cells were considered to be positive for Group I mGluRs, and labeling appeared to be membrane-associated. However, future studies using electron microscopy are required to definitively determine whether this labeling is pre- or postsynaptic.

CONCLUSION

Group I mGluRs are expressed throughout the NTS and are present on a variety of cell types known to influence autonomic nervous system function within the NTS. Cells expressing Group I mGluRs were more likely CVLM projecting or nitroxidergic (nNOS) compared with GABAergic (GAD67) or catecholaminergic (TH). Regarding NTS cells that project to the CVLM, a greater percentage expressed Group I mGluRs compared with those that contained nNOS, GAD67, or TH. Interestingly, a high proportion of nNOS-IR CVLM projecting cells expressed Group I mGluRs. This study provides anatomical evidence supporting a role of Group I mGluRs in the modulation or activation of autonomic neurons in the NTS.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeffrey T. Potts for assistance in establishing the immunohistochemical protocol for GAD67 and Dr. Fabio Gallazzi for synthesizing the blocking peptide for mGluR 5. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Sarah Friskey for her assistance with the surgical preparations, David McGovern and Luise King, DVM for their assistance with tissue preparations and immunohistochemical protocols, and Heather Dantzler for assistance with immunoblot analysis. This study was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Grants HL-55306 and HI 54669.

Abbreviations

- AP

area postrema

- BS

brain stem

- CB

cerebellum

- CNS

central nervous system

- CTX

cortex

- CS

calamus scriptorius

- CVLM

caudal ventrolateral medulla

- FG

Fluoro-Gold

- GAD67

glutamic acid decarboxylase isoform 67

- Glu

L-glutamate

- HR

heart rate

- IR

immunoreactive

- KYN

kynurenic acid

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- NDS

normal donkey serum

- NGS

normal goat serum

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RM

repeated measures

- SNA

sympathetic nerve activity

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

REFERENCES

- Aicher S. Heterogeneous receptor distribution in autonomic neurons. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aicher S, Milner T, Pickel V, Reis D. Anatomical substrates for baroreflex sympathoinhibition in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 2000;51:107–110. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen M, Kunze D. Nucleus tractus solitarius: Gateway to neural circulatory control. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:93–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T, Hermes S, Andresen M, Aicher S. Cranial visceral afferent pathways through the nucleus of the solitary tract to caudal ventrolateral medulla or paraventricular hypothalamus: target-specific synaptic reliability and convergence patterns. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11893–11902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2044-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R, Jarvina E, Sawchenko P. Effects of selective sinoaortic denervation on phenylephrine-induced activational responses in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Neuroscience. 2000;101:165–178. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00332-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R, Sawchenko P. Organization and transmitter specificity of medullary neurons activated by sustained hypertension: implications for understanding baroreceptor reflex circuitry. J Neurosci. 1998;18:371–387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00371.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Ling E-H, Horowitz J, Bonham A. Synaptic transmission in nucleus tractus solitarius is depressed by group II and III but not group I presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in rats. J Physiol. 2002;538:773–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciriello J. Brainstem projections of aortic baroreceptors afferents fibers in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1983;36:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(83)90482-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn P, Pin J-P. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dampney R. Functional organization of central pathways regulating the cardiovascular system. Physiol Rev. 1994;74:323–364. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1994.74.2.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias A, Vitela M, Colombari E, Mifflin S. Nitric oxide modulation of glutamatergic, baroreflex, and cardiopulmonary transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:H256–H262. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01149.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T. Characterization of modulatory effects of postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors on calcium currents in rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res. 2004;1024:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley C, Moffitt J, Hay M, Hasser E. Glutamate in the nucleus of the solitary tract activates both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R1858–R1866. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley C, Vogl H, Mueller P, Hasser E, Hay M. Cardiovascular response to group I metabotropic glutamate receptors activation in NTS. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1469–R1478. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong A, Stornetta R, Foley C, Potts J. Immunohistochemical localization of GAD67-expressing neurons and processes in the rat brainstem: subregional distribution in the nucleus tractus solitarius. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:274–290. doi: 10.1002/cne.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum S, Miller R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate excitatory transmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2251–2558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-06-02251.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum S, Miller R. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors produces reciprocal regulation of ionotropic glutamate receptors and GABA responses in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius of the rat. J Neurosci. 1993a;13:1636–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01636.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum S, Miller R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors depress afferent excitatory transmission in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. J Neurophysiol. 1993b;70:2669–2672. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon F. Aortic baroreceptor reflexes are mediated by NMDA receptors in caudal ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:R628–R633. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1987.252.3.R628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon F, Sved A. Neurotransmitters in central cardiovascular regulation: glutamate and GABA. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:522–524. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet P. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Neurosci. 2006;7:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nrn1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M, McKenzie H, Lindsley K, Dietz N, Bradley S, Conn P, Hasser E. Heterogeneity of metabotropic glutamate receptors in autonomic cell groups of the medulla oblongata of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403:486–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes S, Mitchell J, Aicher S. Most neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract do not send collateral projections to multiple autonomic targets in the rat brain. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:539–551. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang C, Hay M. Expression of metabotropic glutamate receptors in nodose ganglia and the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol. 2001;284:H457–H462. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske I, Morrison S, Cravo S, Reis D. Identification of baroreceptor reflex interneurons in the caudal ventrolateral medulla. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:R169–R178. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.1.R169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y-H, Bailey T, Andresen M. Cranial afferent glutamate heterosynaptically modulates GABA release onto second-order neurons via distinctly segregated metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9332–9340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Fuxe K, Goldstein M. Rat medulla oblongata. II. Dopaminergic, noradrenergic (A1 and A2) and adrenergic neurons, nerve fibers, and presumptive terminal processes. J Comp Neurol. 1985a;233:308–332. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Woodward D, Smith W, Fuxe K. Rat medulla oblongata. IV. Topographical distribution of catecholaminergic neurons with quantitative three-dimensional computer reconstruction. J Comp Neurol. 1985b;233:350–364. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantzides A, Badoer E. nNOS-containing neurons in the hypothalamus and medulla project to the RVLM. Brain Res. 2005;1037:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiely J, Gordon F. Role of rostral ventrolateral medulla in centrally mediated pressor responses. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1549–H1556. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.4.H1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence A, Castillo-Melendez M, McLean K, Jarrott B. The distribution of nitric oxide synthase-, adenosine deaminase- and neuropeptide Y-immunoreactivity through the entire rat nucleus tractus solitarius: effect of unilateral nodose ganglionectomy. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;15:27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence A, Jarrott B. Neurochemical modulation of cardiovascular control in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;48:21–53. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S, Machado B, Ohta H, Talman W. Processing of cardiopulmonary afferent input within the nucleus tractus solitarii involves activation of soluble glutamate cyclase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;203:327–328. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90737-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L-H, Cassell M, Sandra A, Talman W. Direct evidence for nitric oxide synthase in vagal afferents to the nucleus tractus solitarii. Neuroscience. 1998;84:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L-H, Emson P, Talman W. Apposition of neuronal elements containing nitric oxide synthase and glutamate in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rat: a confocal microscope analysis. Neuroscience. 2000;96:341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00560-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L-H, Talman W. Vesicular glutamate transporters and neuronal nitric oxide synthase colocalize in aortic pressor afferent neurons. J Chem Neuroanat. 2006;32:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chen C-Y, Bonham A. Metabotropic glutamate receptors depress vagal and aortic baroreceptor signal transmission in the NTS. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1682–H1694. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy A. Central autonomic pathways. In: Loewy A, Spyer K, editors. Central regulation of autonomic functions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel D, Schreihofer A. Central respiratory modulation of barosensitive neurons in rat caudal ventrolateral medulla. J Physiol. 2006;572:881–896. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K, Tsui H-C, Kagiyama S, Abe I, Fujishima M. Subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract of rats. Brain Res. 1999;842:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelowitz D, Yang M, Andresen M, Kunze D. Localization and retention in vitro of fluorescently labeled aortic baroreceptor terminals on neurons from the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res. 1992;581:339–343. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90729-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minson J, Llewellyn-Smith I, Arnolda L, Pilowsky P, Chalmers J. c-Fos expression in central neurons mediating the arterial baroreceptor reflex. Clin Exp Hyper. 1997;19:631–643. doi: 10.3109/10641969709083175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt J, Heesch C, Hasser E. Increased GABAa inhibition of the RVLM after hindlimb unloading in rats. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:R604–R614. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00341.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta H, Bates J, Lewis S, Talman W. Actions of S-nitrosocysteine in the nucleus tractus solitarii are unrelated to release of nitric oxide. Brain Res. 1997;746:98–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton J, Kasparov S, Paterson D. Nitric oxide and autonomic control of heart rate: a question of specificity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:626–631. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawloski-Dahm C, Gordon F. Evidence for a kynurenate-insensitive glutamate receptor in nucleus tractus solitarii. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1611–H1615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain. Academic Press; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pin J-P, De Colle C, Bessis A-S, Acher F. New perspectives for the development of selective metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;375:277–294. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J-P, Duvoisin R. The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1–26. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(94)00129-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes B, Van Bockstaele E. Divergent projections of catecholaminergic neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract to limbic forebrain and medullary autonomic brain regions. Brain Res. 2006;1117:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross C, Ruggiero D, Reis D. Projections from the nucleus tractus solitarii to the rostral ventrolateral medulla. J Comp Neurol. 1985;242:511–534. doi: 10.1002/cne.902420405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp D. Unveiling the functions of presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in the central nervous system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:12–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer A, Guyenet P. Baro-activated neurons with pulse-modulated activity in the rat caudal ventrolateral medulla express GAD67 mRNA. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1265–1277. doi: 10.1152/jn.00737.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekizawa S-I, Bonham A. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors on second-order baroreceptor neurons are tonically activated and induce a Na+-Ca2+ exchange current. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:882–892. doi: 10.1152/jn.00772.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spyer K. The central nervous organization of reflex circulatory control. In: Loewy A, Spyer K, editors. Central regulation of autonomic functions. Oxford University Press; New York: 1990. pp. 168–188. [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta R, Guyenet P. Distribution of glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNA-containing neurons in rat medulla projecting to thoracic spinal cord in relation to monoaminergic brainstem neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1999;407:367–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman W. NO and central cardiovascular control: a simple molecule with a complex story. Hypertension. 2006;48:552–554. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238142.22799.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman W, Alonso D, Reis D. Chronic lability of arterial pressure in the rat does not evolve into hypertension. Clin Sci. 1980;59:405ss–407s. doi: 10.1042/cs059405s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman W, Dragon D, Ohta H, Lin L-H. Nitroxidergic influences on cardiovascular control by NTS: a link with glutamate. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:169–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard E, Sapru H. Cardiovascular responses to activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nTS of the rat. Brain Res. 2002;952:321. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach J, Loewy A. Projections of the aortic nerve to the nucleus tractus solitarius in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1980;188:247–251. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessondorf M. Fluoro-Gold: composition, and mechanism of uptake. Brain Res. 1991;553:135–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90241-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston M, Wang H, Stornetta R, Sevigny C, Guyenet P. Fos expression by glutamatergic neurons of the solitary tract nucleus after phenylephrine-induced hypertension in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;460:525–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.10663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]