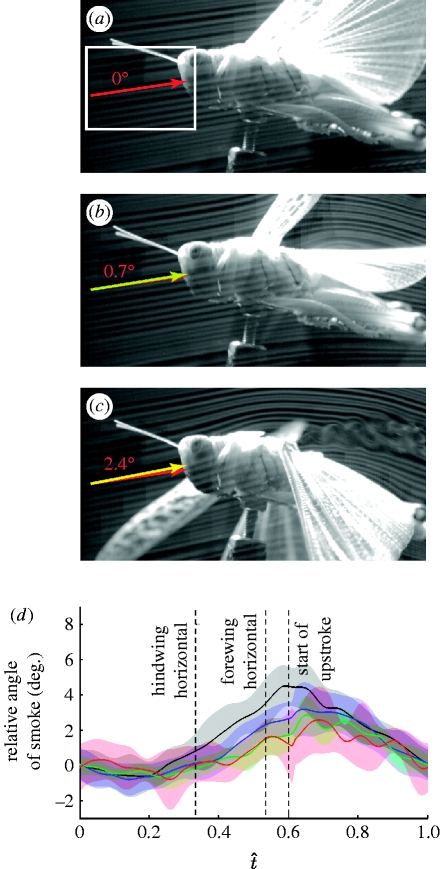

Figure 8.

(a–c) Smoke visualization of a tethered locust at three stages of the downstroke. (a) t̂=0.0: beginning of the downstroke; (b) t̂=0.33: mid-downstroke, when the hindwing is horizontal; and (c) t̂=0.55: late downstroke, when the forewing is horizontal. The smoke lines are positioned to meet the hindwing at 50% of its length when the wing is horizontal. The red arrows indicate the angle of the smoke at the start of the downstroke. The yellow arrows show the instantaneous angle of the smoke. The angle between the red and the yellow arrows indicates the change in the induced flow since the start of the downstroke. The graph in (d) plots the change in smoke angle against the normalized time based on automated measurement of the change in the angle of the smoke relative to the start of the downstroke. The white rectangle in (a) indicates the region of interest for the automated angle analysis. The solid lines denote the mean instantaneous change in smoke angle at four distances along the wing length(black, 20%; blue, 40%; green, 60%; red, 80%), and the shaded region around those lines displays the instantaneous standard deviation at that point on the wing. The amplitude of the periodic change in the induced flow is greatest near the wing root (d), where the amplitude is still less than 2.5°. This is an order of magnitude smaller than the periodic changes in the wing angle of attack (figure 6c,f). It is therefore reasonable to base aerodynamic inferences about the effects of periodic wing deformations upon our kinematic measurements of periodic changes in the wing angle of attack, albeit that these do not exactly measure the true effective aerodynamic angle of attack.