Abstract

Androgen receptor (AR), a member of the steroid receptor family, is a transcription factor that has an important role in the regulation of both prostate cell proliferation and growth suppression. AR coactivators may influence the transition between cell growth and growth suppression. We have shown previously that the internally spliced ARA70 isoform, ARA70β, promotes prostate cancer cell growth and invasion. Here we report that the full length ARA70α, in contrast, represses prostate cancer cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth in vitro and inhibits tumor growth in nude mice xenograft experiments in vivo. Further, the growth inhibition by ARA70α is AR-dependent and mediated through induction of apoptosis rather than cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, AR with T877A mutation in LNCaP cells decreased its physical and functional interaction with ARA70α, facilitating the growth of LNCaP cells. The tumor suppressor function of ARA70α is consistent with our previous findings that ARA70α expression is decreased in prostate cancer cells compared with benign prostate. ARA70α also reduced the invasion ability of LNCaP cells. Although growth inhibition by ARA70α is AR-dependent, the inhibition of cell invasion is an androgen-independent process. These results strongly suggest that ARA70α functions as a tumor suppressor gene.

Androgen receptor (AR) is a transcription factor that regulates growth and differentiation of prostate cells. It mediates transcriptional activation through a series of events including ligand binding, DNA binding to androgen response elements, and interaction with various cofactors that converge on the general transcription machinery.1 Cofactors of steroid receptors are required for activator/repressor-dependent transcription but not for basal level transcription. Mounting evidence strongly suggests the function of AR and its coactivators in promoting cancer cell growth.2,3,4,5,6 Recently, however, several AR coactivators with reduced nuclear expression in prostate cancer, including p44 and ART-27, have been shown to facilitate AR-mediated growth suppression.7,8 Whether other AR cofactors that display reduced expression in prostate cancer, such as ARA70, also mediate AR-dependent growth suppression remains to be examined.

ARA70 was first identified as a gene fused with the ret oncogene in thyroid carcinoma9 and subsequently as an AR coactivator in the presence of a ligand.10 ARA70 has two isoforms: the full length 70 kDa ARA70α and the internally spliced 35 kDa ARA70β.11 ARA70α interacts with AR ligand-binding domain via its N-terminal FXXLF motif and with the N-terminus of AR independently of FXXLF.12,13,14 The interaction between AR and ARA70α also stabilizes the AR, increasing its expression and translocation into the nucleus.14 ARA70α mediates the interaction of AR with the basal transcription machinery, possibly through PCAF and TFIIB.11

Altered expression of ARA70 has been documented in breast,15 ovarian,16 and prostate cancers. In prostate cancer, we and others have demonstrated reduced ARA70α transcript levels.11,17,18,19 However, the levels of ARA70β are increased in prostate cancer.20 The distinct patterns of ARA70α and ARA70β expression in prostate cancer suggest functional difference between the two isoforms. Indeed, we showed that ARA70β functions as an oncogene in promoting prostate cancer cell growth and invasion.20 In this study, we demonstrated that ARA70α functions as a tumor suppressor gene in prostate cancer in in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Cell Proliferation, and Anchorage-Independent Assays

LNCaP and PC3 cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1 U/ml of penicillin, 1 μg/ml of streptomycin, and 2 μg/ml of puromycin where required. To measure the proliferation rate, 2 × 104 cells were seeded into 6-well plates. At the appropriate time points, the cells were treated with 0.25% trypsin and 0.38 mg/ml of EDTA (Gibco) and were counted by using a hemocytometer (Reichert, Buffalo, NY).8 For the anchorage-independent assay, 1.5 × 104 cells/ml were mixed with 0.35% low melting point SeaPlaque GTG agarose (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ) in the appropriate medium and were plated on top of solidified agarose/medium substrate. Fresh 0.35% agarose/medium mix was added every 3 days until the colonies were counted.8

Apoptosis Assays

3,3′-diethylcarbocyanine iodide (DiOC2(3); Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to assess mitochondrial membrane potential status. Cells were detached by using 0.25% trypsin and 0.38 mg/ml of EDTA; 1 × 106 cells were resuspended in the appropriate medium, treated with 50 nmol/L of DiOC2(3), and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30 minutes. After washing with PBS, the stained cells were analyzed on a flow cytometer with 488 nm excitation light and Texas Red dye emission filter. To determine whether the cytoplasmic membrane of the cells lost its asymmetric distribution of phosphatidylserine, the cells were detached as described above and were treated with annexin V conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen). The cells were resuspended in 100 μl of the annexin V binding buffer (10 mmol/L of HEPES, 140 mmol/L of NaCl, and 2.5 mmol/L of CaCl2, pH 7.4). Cell suspension was then treated with 1 μg/ml of propidium iodide and 5 μl of annexin V conjugate. After room temperature incubation for 15 minutes, the stained cells were analyzed by using flow cytometer, measuring the emission at 530 nm and >575 nm.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell extracts were prepared from immortalized benign prostate cells and the following commonly used prostate cancer cells: LNCaP and PC3. They were subjected to electrophoresis on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for western blot analysis. Immunoblots were blocked for 30 minutes in 3% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 (20 mmol/L of Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mmol/L of NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20). Blots were incubated with antibodies raised against ARA70α,20 androgen receptor and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), apoptosis-inducing factor, Bax, Bcl-XL, cleaved caspase 3, caspase 8, and p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) for 2 hours at room temperature, washed with Tris-buffered saline Tween 20 three times, and incubated for 1.5 hours with the secondary antibody (1:5000; Amersham Biosciences). Antibodies were diluted with 2% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline Tween 20. The protein bands were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden).

Nude Mice Xenograft Experiments

The cells were grown to 80% confluency, detached from the support by using 0.25% trypsin/EDTA, and washed with PBS. The cell pellet was resuspended in the Matrigel Matrix phenol red-free basement membrane (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to the final concentration 7 × 106 cells/ml. One hundred microliters of the suspension was subcutaneously injected into 4- to 5-week-old male nude mice (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD). The tumor growth was monitored twice a week by measuring the three dimensions of the xenografts. The tumor volume was calculated as width × length × height × 1/2.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining for cleaved caspase 3 was performed by using single label immunohistochemistry with the NexES, an automated immunostainer and detection system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded, 4-μm sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded alcohols, and rinsed in distilled water. All incubations were performed at 37°C unless otherwise noted. After deparaffinization, heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed by microwaving sections with 0.01M, pH 6.0 citrate buffer for 20 minutes in a 1200 watt microwave oven. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by application of hydrogen peroxide for 4 minutes. Primary antibody was added followed by the application of a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit for 8 minutes, then by the application of streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase for 8 minutes. The chromogen, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine/hydrogen peroxide mix was applied for 8 minutes and then enhanced with copper sulfate for 4 minutes. Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with permanent media.

Matrigel Invasion Assays

Cells were resuspended in the medium without serum at 105/ml, and 0.5 ml were loaded into the inserts of Biocoat Matrigel 24-well invasion chambers (BD Biosciences). The lower chambers were filled with 750 μl of the medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum as the chemoattractant. After 24 hours, the inserts were removed and the noninvading cells were cleared away from the upper surface of the membrane by using a cotton swab. The cells that migrated to the lower surface of the membrane were stained with Diff Quik stain (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and counted under a microscope.

Mutational Analysis of ARA70 in Cancer

The sequence of coding region of ARA70α was analyzed with 20 macro-dissected matched frozen benign and cancerous prostate tissue selected on sequential basis. The patients with prostate cancer were from 56 to 76 years old with a Gleason score from 6 to 8 (n = 10 for score 6, n = 6 for score 7, and n = 4 for score 8) and Stage from T2 (n = 10) to T3 (n = 10). Genomic DNA was isolated with PUREGENE DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN; category number 7000A) with primers positioned in the introns adjacent to the exons being targeted for amplification; genomic DNA was then amplified by PCR and sequenced by the University of Arizona DNA sequencing facility.

RNA Interference for ARA70α, and RT-PCR Analysis for ARA70α, ARA70β, and AR

The small-interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of ARA70α was performed by using annealed RNA oligonucleotides 5′-GGAAAGGAUAAAAAUGGGATT-3′ and 5′-UCCCAUUUUUAUCCUUUCCTT-3′ (Ambion, Austin, TX), which were transfected into cells by using HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The target sequence for these nucleotides reside in the internally spiced region of the ARA70α, ensuring the specificity of down-regulation of ARA70α.

Total RNA was extracted from LNCaP cells by using the RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Ambion). cDNA was synthesized by using the RETROscript kit (Ambion) and used as template in PCR reactions to detect ARA70α, ARA70β, AR, and 18S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA). The oligonucleotides for detection of ARA70α (5′-AGTCGTGAAACCAGTGAGAAG-3′, 5′-CCCATTTTTATCCTTTCCTTCTTTC-3′) were selected to hybridize in the internal deletion region missing from ARA70β. The oligonucleotides for specific detection of ARA70β (5′-ACCTTGGAGAACAGTCAGCA-3′, 5′-TCACATCTGTAGAGGAGTTCGAT-3′) were selected so that the left primer had 3′ sequence cagCA, which is unique to ARA70β splice junction (ARA70α has cagAC); the right primer starts from stop codon and anneals to both ARA70α and ARA70β. The primers for amplification of AR were 5′-CCTCCTGTAGTTTCAGATTAC-3′ and 5′-TTTCCACCCCAGAAGACCTGC-3′, and the primers for 18S rRNA were 5′-AGGAATTGACGGAAGGGCAC-3′ and 5′-GTGCAGCCCCGGACATCTAAG-3′.

Statistical Analysis of the Results

The statistical analyses of the above results were performed by using the pairwised Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant if P < 0.05.

Results

Establishing LNCaP and PC3 Cells Stably Overexpressing ARA70α

To dissect the function of ARA70α, we constructed the retroviral vector overexpressing full length ARA70α (pBabe-ARA70α) and used this construct to establish clonal stable LNCaP and PC3 cell lines stably overexpressing ARA70α (LNCaP-ARA70α and PC3-ARA70α, respectively). Three independent clonal cell lines of each were used for each experiment. LNCaP and PC3 cells with pBabe vector (LNCaP-pBabe and PC3-pBabe) were used as controls. Figure 1A demonstrated that ARA70α was overexpressed as a full length protein in stable LNCaP-ARA70α cells.

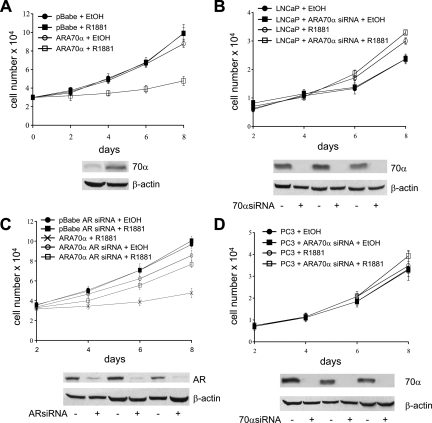

Figure 1.

ARA70α inhibits cell growth in an androgen and AR-dependent manner. A: ARA70α inhibits growth of LNCaP cells in the presence of androgen R1881 (empty squares). Without R1881 (empty circles), LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α grow at the rate similar to that of control cells, both in the presence (black squares) and absence (black circles) of R1881. The expression of ARA70α was confirmed by using western blot (lower panels). B: Endogenous ARA70α limits the growth rate of LNCaP cells. LNCaP cells treated with ARA70α-specific siRNA (squares) and untreated LNCaP cells (circles) were grown in the presence (empty circles and squares) or absence (black circles and squares) of R1881. C: Growth-inhibitory effect of ARA70α depends on the presence of AR. AR levels were decreased by using siRNA (lower panels). AR knockdown with siRNA reversed the growth inhibition by ARA70α overexpression (empty circles and squares) in LNCaP cells, and the cells were grown in the presence (squares) and absence (circles) of R1881. Included for comparison are LNCaP-ARA70α cells not treated with AR siRNA in the presence of R1881 (crosses). D: ARA70α does not influence the growth of PC3 cells. PC3 cells treated with ARA70α-specific siRNA (squares) and untreated PC3 cells (circles) were grown in the presence (empty circles and squares) or absence (black circles and squares) of R1881.

ARA70α Overexpression Inhibits Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation, Anchorage-Independent Growth in Vitro, and Xenograft Tumor Growth in Vivo

Analysis of cell proliferation of LNCaP-ARA70α and LNCaP-pBabe by cell counting revealed that ARA70α inhibits cell growth (P = 0.0003) in the presence of synthetic androgen ligand R1881 (Figure 1A). To further validate the inhibitory effect of ARA70α, we abolished ARA70α expression in wild-type LNCaP cells by using siRNA (Figure 1B) and compared their growth rate with that of LNCaP cells with wild-type ARA70α levels. The ARA70α siRNA that we designed targets the ARA70α internally spliced region missing from ARA70β. Therefore, it did not affect ARA70β levels, which we confirmed by RT-PCR at RNA levels and western blotting at protein levels (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We also examined the levels of AR, and its expression did not change when ARA70α was knocked down (Supplemental Figure S1, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). As expected, LNCaP cells with reduced expression of ARA70α grew faster than the wild-type cells (Figure 1B) in the medium supplemented with R1881. The reduction of cell proliferation in LNCaP-ARA70α as compared with LNCaP-pBabe was not observed in androgen-free medium (data not shown), indicating that the inhibitory effect of ARA70α on the cell growth may be dependent on the activity of AR. To confirm this, we abolished the expression of AR by using siRNA (Figure 1C) knockdown followed by growth kinetic analysis. The cell proliferation rate of LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α under AR knockdown condition was close to that of LNCaP-ARA70α cells, both in androgen-free medium (data not shown) and medium supplemented with R1881 (Figure 1C). As previously reported, AR knockdown by siRNA reduced the growth of LNCaP cells21,22,23 and had a delayed effect24 (Supplemental Figure S2, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We next analyzed the effect of ARA70α on the growth of PC3 cells (negative or low AR) by using PC3-ARA70α and PC3-pBabe cells. The presence or absence of ARA70α had no statistically significant effect on the growth of PC3 cells, both in androgen-free (data not shown) and androgen-supplemented medium (Figure 1D).

Similarly, the inhibitory effect of ARA70α on the growth of attached cells could also be observed in cells grown in suspension medium in anchorage-independent assays. In the presence of 10 nmol/L of R1881, the ARA70α-overexpressing LNCaP cells formed about 50% less colonies than control LNCaP-pBabe cells (Figure 2, A and B). In addition, the majority of these colonies were significantly smaller than those formed by the control cell line (Figure 2A). In the absence of androgen, LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α and the control LNCaP-pBabe cells formed a comparable number of colonies (Figure 2B).

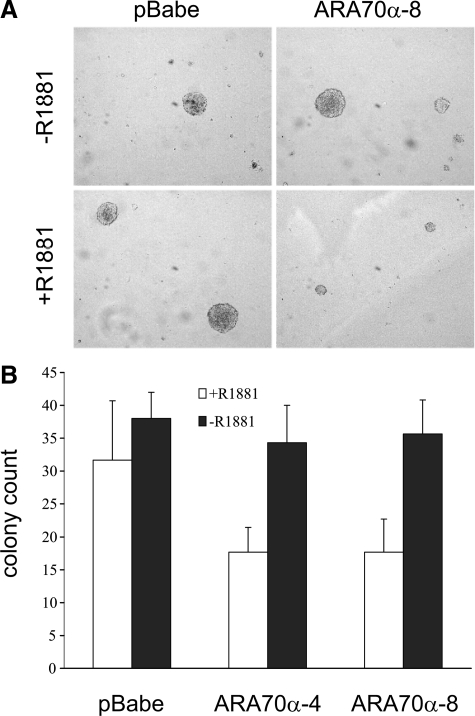

Figure 2.

ARA70α inhibits growth of LNCaP cells in anchorage-independent assays. Cells were grown suspended in agarose medium in the presence or absence of R1881. A: In the presence of R1881, ARA70α-overexpressing cell line produced fewer and smaller colonies than in the absence of R1881 compared with the control cells. B: Two clonal LNCaP cell lines overexpressing ARA70α yielded the same number of colonies as the control cell line in the absence of R1881 (black columns), but this number decreased by 50% in the presence of R1881 (white columns).

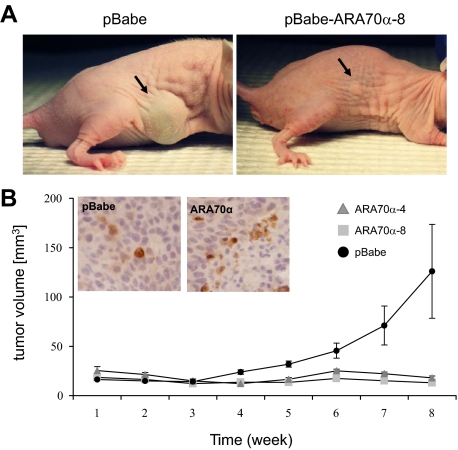

To determine the inhibitory effect of ARA70α on growth in vivo, we examined tumor growth in subcutaneous nude mice xenografts with LNCaP-ARA70α and LNCaP-pBabe cells (Figure 3A). In 10 mice of each group, 7 × 106 cells were injected subcutaneously. After the initial lag phase, tumors started to develop and grow in the mice injected with control LNCaP-pBabe cells. However, the tumor development in mice injected with LNCaP-ARA70α cells was minimal (Figure 3B). Consistent with in vitro experiments, there is an increased positivity for cleaved caspase 3 in LNCaP-ARA70α (right) compared with LNCaP-pBabe (left) tumor cells by immunohistochemistry.

Figure 3.

ARA70α reduced tumor growth in nude mice xenografts. A: Growth suppression by ARA70α on subcutaneous tumor xenografts, 8 weeks after injection, is shown. B: Tumor volume showing LNCaP-ARA70α cells have greatly reduced potential in tumorigenesis. Nude mice were injected either with 7 × 106 LNCaP-ARA70α cells or LNCaP-pBabe cells. Tumor size was measured twice a week. Black bars, control LNCaP-pBabe cells; white bars, LNCaP-ARA70α−4 cells; gray bars, LNCaP-ARA70α−8 cells; Error bars represent SE. Inset: Increased cells positive for cleaved caspase 3 in LNCaP-ARA70α (right) compared with LNCaP-pBabe (left) cells.

Together, the results of the above studies confirm the presence of ARA70α-reduced cellular proliferation, and this growth inhibition is androgen and AR dependent.

Increased Apoptosis in LNCaP Cells Overexpressing ARA70α

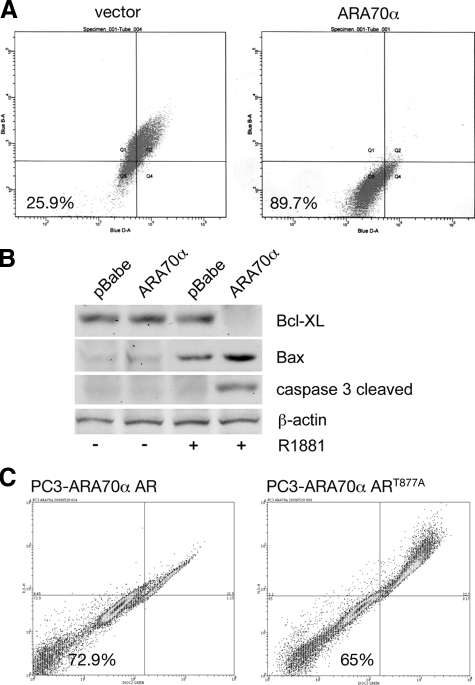

To investigate the mechanism by which ARA70α inhibits cell proliferation, we asked whether the growth inhibition is because of cell cycle arrest or increased apoptosis. Flow cytometry profile of LNCaP-ARA70α and control LNCaP-pBabe cells did not reveal any significant changes in distribution of cells in various phases of the cell cycle (Table 1). However, we observed a sub-G1 cell population of cells, an indication of DNA fragmentation as a result of apoptosis (data not shown). To investigate further the possible role of apoptosis as a mechanism of ARA70α-dependent growth inhibition, we stained live cells with the cyanine dye DiOC2(3) followed by flow cytometry analysis. This dye enters mitochondria and emits a red and green signal on excitation due to dye stacking; reduced emission is a sign of decreased mitochondrial membrane potential. We observed that in the cells overexpressing ARA70α, the population of cells with reduced emission increased threefold, from 25.9% to 89.7% (Figure 4A), indicating that certain cells in this population are subjected to mitochondrial damage. Western blot analysis was performed to examine proapoptotic markers, including caspase 3, cleaved caspase 3, caspase 8, Bax, PUMA, apoptosis-inducing factor, and antiapoptotic Bcl-xL. The results revealed increased levels of cleaved caspase 3 and Bax but decreased levels of Bcl-xL in ARA70α overexpressing LNCaP cells as compared with the control LNCaP-pBabe cells (Figure 4B). The changes in these apoptotic genes are androgen-dependent under the influence of ARA70α (Figure 4B). Thus, the decreased cell proliferation by ARA70α is because of increased apoptotic rather than decreased cell cycle events.

Table 1.

Growth Suppression by ARA70α Is Not Because of Cell Cycle Regulation

| Cell Cycle Phase | pBabe | pBabe-ARA70α |

|---|---|---|

| S-phase, % | 5.26 ± 0.69 | 5.95 ± 0.32 |

| G2/M-phase, % | 2.62 ± 0.16 | 2.15 ± 0.17 |

Figure 4.

Increased number of cells undergoing apoptosis in LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α. A: LNCaP-ARA70α and LNCaP-pBabe cells were grown in androgen medium, harvested, stained with dye DiOC2(3), and analyzed by flow cytometry (488 nm excitation, 530/30 nm bandpass and 650 nm longpass filters). B: Androgen-dependent changes in apoptotic regulators in ARA70α overexpressing cells. LNCaP-pBabe and LNCaP-ARA70α cells were grown either in the presence or absence of androgen and the levels of Bcl-XL, Bax, and cleaved caspase 3 were analyzed using western blot. C: Effect of mutated AR on the extent of apoptosis caused by overexpression of ARA70α. PC3 cells stably overexpressing ARA70α were transiently transfected either with wild type AR or the ART877A mutant. Harvested cells were stained with DiOC2(3) and analyzed as above.

Impaired Physical and Functional Interaction between ARA70α and Mutated ART877A in LNCaP Cells, Leading to Accelerated Prostate Cancer Cell Growth

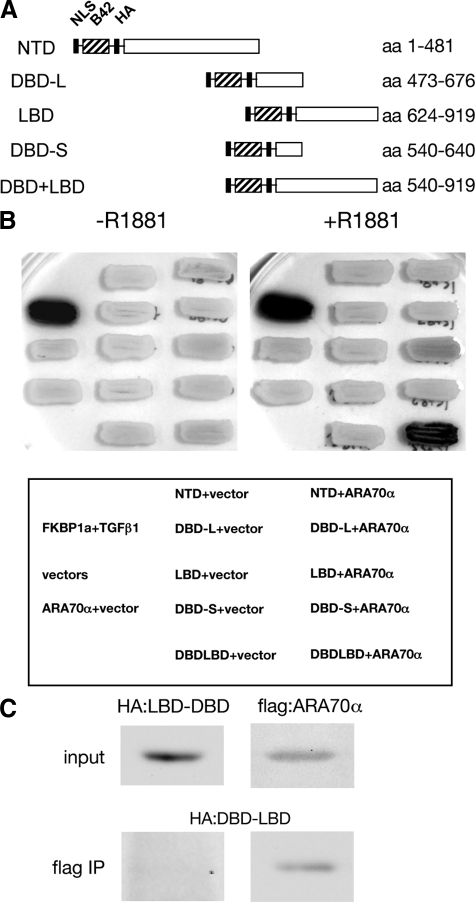

We used a yeast two-hybrid system to elucidate the mode of interaction between AR and ARA70α. We created a yeast expression vector with ARA70α fused to LexA DNA binding domain and a series of vectors containing various domains of AR fused to B42 transcription activation domain (Figure 5A). The protein expression of each domain in Figure 5A was confirmed by western blot analysis (data not shown). Although we observed a weak interaction between the full length ARA70α and the ligand-binding domain of AR in the two-hybrid assay, the interaction was strongest when both the ligand-binding and DNA-binding domains of AR were present (Figure 5B). Importantly, this interaction was dependent on the presence of the synthetic androgen R1881 in the yeast growth medium (Figure 5B, left versus right panel). The interaction between the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and ligand-binding domain (LBD) region of AR and ARA70α was verified in co-immunoprecipitation experiments. A construct of AR containing DBD and LBD regions was transfected into PC3 cells. The presence of truncated AR DBD and LBD protein was detected by western blot analysis after incubation with flag antibody to co-immunoprecipitate flag-tagged ARA70α (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Strong interaction between AR and ARA70α requires both AR DBD and LBD domains. A: Schematic domains of two-hybrid constructs containing the nuclear localization sequence (NLS), the B42 transcription activation domain, hemaglutinin tag (HA), and individual domains of AR (NTD, N-terminal domain; DBD-L, full length DNA-binding domain; DBD-S, short version of the DNA-binding domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; DBD+LBD, DNA-binding domain and ligand-binding domain). B: Interaction between AR and ARA70α in a two-hybrid overlay test. The yeast patches were grown on the selective medium containing galactose in the presence or absence of R1881. The expression of the reporter gene was visualized by lysing the cells in situ in the presence of the chromogenic substrate x-gal. Yeast expressing two-hybrid constructs of FKBP1a and transforming growth factor β1 were used as a positive control. The tests were performed with ARA70α fused to the LexA DNA-binding domain and individual AR domains fused to the B42 transactivation domain. C: Co-immunoprecipitation of LBD+DBD domains of AR with ARA70α. Lysate was incubated with flag M2 antibody and immunoprecipitated AR domains were detected by western blot using HA antibody.

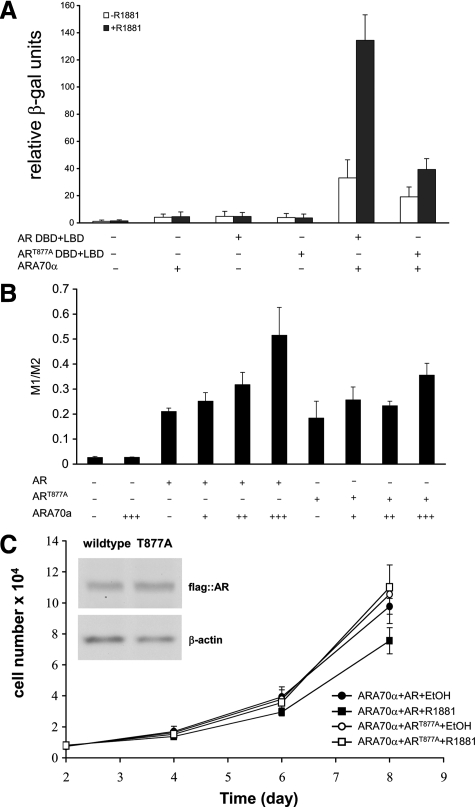

Next, we analyzed the two-hybrid interaction of ARA70α with mutated ART877A, a widely studied mutation isolated from LNCaP prostate cancer cells. We showed that the R1881-dependent interaction between the AR ligand-DNA-binding domain and ARA70α is decreased about threefold (Figure 6A) with mutated ART877A compared with wild-type AR in which a quantitative yeast two-hybrid liquid assay was used. To determine the functional relevance of the impaired interaction between ART877A and ARA70α in prostate cancer cells, we performed a luciferase assay (Figure 6B) by using a synthetic promoter containing four copies of the AR-binding element as a reporter.25 We observed a dose-dependent increase in reporter activity when both ARA70α and the wild-type AR were present. The reporter activity was reduced by about one third when the mutated AR was substituted for the wild-type.

Figure 6.

The T877A mutation in AR weakens the physical and functional interactions between AR and ARA70α. A: The expression of the β-galactosidase reporter gene was measured in the liquid assay in cells expressing ARA70α and either wild-type AR or ART877A in the presence or absence of the synthetic androgen R1881. B: Impaired ARA70α transcriptional activity with mutated AR in dual luciferase assays. LNCaP cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors carrying ARA70α, the reporter gene (under the control of promoter containing four androgen-responsive elements), and either wild-type AR or ART877A. The reporter gene activity was expressed as a ratio between the firefly and renilla luciferase luminescence (M1/M2). C: Growth kinetics revealed that T877A mutation in AR undermined the growth suppressive function of ARA70α.

Next, we performed growth kinetic analysis with PC3 cells virally transfected with ARA70α and either wild-type AR or mutated ART877A. In the cell proliferation assays, wild-type AR produces a greater degree of decrease in proliferation (P = 0.04) compared with ART877A (Figure 6C). To determine whether the effect of reduced growth inhibition of ART877A is because of decreased apoptosis, we performed live cell staining with the cyanine dye DiOC2(3) followed by flow cytometry analysis using PC3-ARA70α cells transfected with wild-type or mutant AR. The results showed a decrease in apoptosis in PC3-ARA70α cells transiently transfected with mutant AR (Figure 4C, right) compared with wild-type AR (Figure 4C, left). The above data indicate impaired physical and functional interaction between ARA70α and mutated ART877A, leading to accelerated prostate cancer cell growth in LNCaP cells. In addition, this confirms that growth inhibitory function of ARA70α is AR-dependent.

Decreased Invasion in LNCaP Cells Overexpressing ARA70α

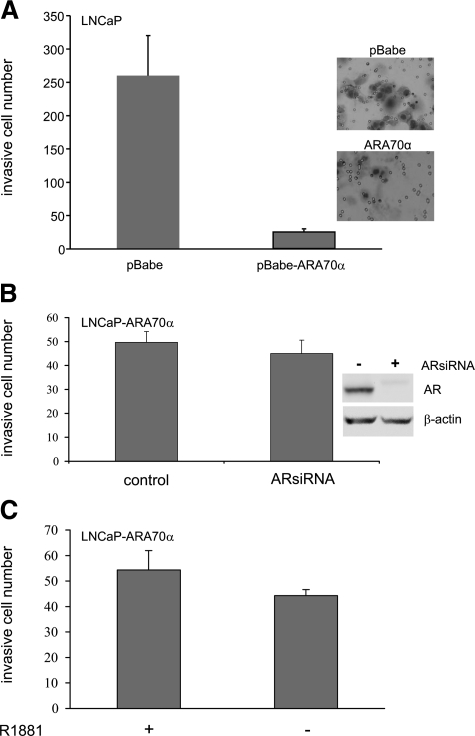

We examined the in vitro invasion capability of LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α in the Matrigel invasion assays with 10% fetal bovine serum as the chemoattractant in the lower chamber and in the presence and absence of R1881. The invasion ability of the ARA70α-overexpressing cells was greatly reduced than that of the control LNCaP-pBabe cells both in the presence (Figure 7A) and absence (data not shown) of androgen. To reveal whether the reduced invasion ability of the ARA70α-overexpressing cells is dependent on the activity of AR, we reduced the levels of AR in the ARA70α-overexpressing (LNCaP-ARA70α) cells by using siRNA (Figure 7B) to knockdown AR expression followed by Matrigel invasion assays. However, the invasiveness of the ARA70α-overexpressing LNCaP cells remained the same in the presence and absence of AR (Figure 7B). As a control, the invasion ability of the LNCaP-pBabe control cells lacking AR was reduced, as expected26 (Y. Li and P. Lee, unpublished data). In addition, ARA70α overexpression in LNCaP cells did not alter its invasion ability in the presence or absence of androgen (Figure 7C). Thus, in contrast to the androgen-dependent nature of growth inhibition, the ability of reduced invasion by ARA70α is an androgen-independent process.

Figure 7.

ARA70α limits invasion potential of LNCaP cells independently of AR in Matrigel invasion assays. A: ARA70α greatly reduced the invasion ability of LNCaP cells. B: siRNA-mediated knockdown of AR in LNCaP-ARA70α cells did not alter the invasion ability. C: Androgen did not affect the invasion ability of LNCaP cells overexpressing ARA70α. LNCaP-pBabe or LNCaP-ARA70α cells, either treated with siRNA or untreated, were seeded into the Matrigel chamber by using fetal bovine serum as chemoattractant. Invading cells were counted and averaged from three fields after Diff-Quik stain.

Decreased Expression and Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Mutations of ARA70α in Human Prostate Cancer

We have previously reported that the expression of ARA70α was decreased in prostate cancer by using a probe with partial overlap between internally deleted region and 3′ splicing region of C-terminus of ARA70β. To ensure that the in situ hybridization probe was specific for ARA70α, we further designed a probe ARA70ID to reside in the region of internal deletion from nt 815-1412. In situ hybridization was performed on 20 prostate cancer prostatectomy specimens to determine ARA70α mRNA expression by using digoxigenin-labeled ARA70α-specific probes. Consistent with our previous results,18 ARA70α was strongly positive in benign prostatic epithelia and decreased in HGPIN and invasive prostate cancer.

ARA70α functions as a tumor suppressor gene, inhibiting prostate cancer growth and invasion. Tumor suppressor genes are often inactivated by somatic point mutations causing cancer. In addition, point mutations have been detected in ARA70α in some cancer cell lines.11 Thus, one possible explanation for altered ARA70α expression in prostate cancer is somatic mutation. We designed primers covering all nine exons of the entire coding region of ARA70α. Sequence analysis of the ARA70 gene was performed after PCR amplification by using genomic DNA isolated from 20 matched laser-captured benign and prostate cancer tissue from radical prostatectomy samples. Our results showed sequence conservation of the coding region of the ARA70 gene across a variety of prostate cancers. Thus, it is unlikely that decreased ARA70α expression in prostate cancer is because of mutation in ARA70.

Interestingly, we identified two previously unreported single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within two of the nine exons of the ARA70 transcript. The first SNP is located within exon 6 of the ARA70 transcript at genomic location 51475302. This SNP shows a C/T replacement. This genetic alteration is present in 4 of 20 samples analyzed (20%) and appears to be homozygous in one of those four samples. The second SNP described in this study occurs at genomic position 51481989 within exon 9 of the ARA70 transcript and shows a C/G replacement. This genetic alteration was observed in 3 of 20 samples analyzed and also appears to be homozygous in one sample. The region of exon 9 where this SNP is located is not translated because of an upstream stop codon very early in exon 9. For this reason, it is unlikely that this C/G alteration would have any effect on the function of the ARA70 protein. The fact that no loss of heterozygosity was observed in any of the informative heterozygous cases provides additional support for the conclusion that these genetic alterations are in fact SNPs and not mutations.

Discussion

The maintenance of benign prostate appears to be a result of balance between proliferation and differentiation, controlled by differential interaction of AR with various cofactors. The changes in the levels of cofactors may shift the balance between suppressing or facilitating cancer progression.27 Here, we demonstrated that the full length ARA70α inhibits growth when overexpressed in prostate cancer LNCaP cells both by in vitro cell proliferation and anchorage-independent assays and by in vivo tumor xenograft experiments. ARA70α exerts its tumor suppressor function in an androgen and AR-dependent fashion. Flow cytometric and apoptotic assays indicate that this inhibitory effect is mediated by increased activity of apoptotic pathways, though the increase in apoptotic cells is not an overt effect. Consistent with a previous report that AR regulates Bax mediated apoptosis (Figure 4B),28 the increase of apoptotic gene Bax and cleaved caspase 3 and decrease in antiapoptotic gene Bcl-XL is androgen and AR-dependent (Figure 4B). The function of ARA70α is in contrast to the splicing variant of ARA70, ARA70β. ARA70β promotes androgen-dependent growth and invasion of prostate cell lines.20 It appears that the changes in splicing of ARA70 into its two distinct variants may be a part of such an AR-dependent mechanism, which switches between either proliferation or growth arrest and/or differentiation.

Overwhelming evidence indicates the critical function of AR in prostate cancer cell proliferation. Recently, a number of AR coactivators were described to have tumor suppressor function: ART27,7 nuclear p44,8 and ARA70α (in this study). Although ARA70α inhibits both growth and invasion of prostate cancer, the growth inhibition is an AR-dependent process and reduction of invasion is an AR-independent process. This is similar to the course of ARA70β with AR-dependent growth stimulation and AR-independent enhancement of prostate cancer invasion. Thus, although AR coactivators interact and facilitate AR function, this coactivator also possesses characteristics independent of AR, contributing to cancer formation and progression. These observations could provide insight for the development of novel therapeutic strategy targeting AR cofactors.27

AR mutations, especially those occurring in the ligand-binding domain of AR, relax ligand specificity and allow other steroid hormones (eg, estrogen or progesterone) to activate target genes.29,30,31 Over 90 AR mutations naturally occurring in prostate cancer have been described.32 The majority of these mutations reside in the DNA and ligand-binding domains with the highest occurrence in androgen-independent cases.33,34 Impaired interaction between mutated AR and cofactor has also been described. An amino acid change of AR in codon 874 from histidine to tyrosine disrupted the interaction between AR and cofactor p160,35 whereas amino acid mutation ARP340L altered the interaction between AR and ART27.36 The widely studied mutation ART877A in LNCaP cells has been shown to promote cell growth and render LNCaP cells resistant to apoptotic stimuli.37 We demonstrated, both in yeast two-hybrid experiments and in cell-based reporter assays, that the interaction between ARA70α and AR is reduced in the presence of the T877A mutation. Our cell proliferation data suggest that the reduced affinity between ARA70α and ART877A leads to decreased growth-inhibition, consistent with the notion that growth suppression function of ARA70α is an AR-dependent process.

Consistent with previous reports, we show that the expression of ARA70α is decreased in prostate cancer. The decreased ARA70α expression in cancer was not because of mutation in the ARA70 coding region. There are four previously identified SNPs that map to locations within the ARA70 transcript region: rs4935213, rs3841340, rs4463801, and rs14818; we identified two novel ARA70 SNPs. The mutational analysis included six cases (out of a total of 20) of high grade cancer characterized with a Gleason score of a predominant four pattern. Although somatic mutation and loss of heterozygotes were not the reason for decreased ARA70α expression in cancer from this study, it will be of great interest to determine in the future whether the decreased ARA70α expression in cancer could be because of deletion of a regulatory element, effects on transcription factors regulating expression, or hypermethylation of regulatory elements.

Alternative splicing is a major form of differential regulation in protein expression in cancer.38,39,40 Frequently, alternative splicing can inactivate tumor suppressors41,42 or create an oncogenic form protein from a tumor suppressor such as KLF6.43 In respect to ARA70, the full length tumor suppressor is spliced into an oncogenic ARA70β form. Because the two isoforms are expressed in the same cells, we performed luciferase assays with ARA70α, ARA70β, and two together to determine whether the expression of one will affect the function of the other. We did not observe additive, synergistic, or antagonistic effects between ARA70α and ARA70β.20 Thus, at least ARA70α and ARA70β are not affecting each other at the levels of transcriptional activation. Cancer-specific transcript variants are currently subject to intense investigation for their potential to serve as biomarkers or novel therapeutic targets.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Peng Lee, M.D., Ph.D., Departments of Pathology and Urology, New York University School of Medicine, New York Harbor Healthcare System, 423 E. 23rd St, Room 6140N, New York, NY 10010. E-mail: peng.lee@nyumc.org.

Supported by Seed Fund from Veteran Affairs Administration, Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Award and New York University School of Medicine Center of Excellence on Urologic Disease Fund to P.L. and NIH R01 grant to M.J.G. (DK058024).

M.L. and Y.L. contributed equally to this work.

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

References

- Brinkmann AO, Blok LJ, de Ruiter PE, Doesburg P, Steketee K, Berrevoets CA, Trapman J. Mechanisms of androgen receptor activation and function. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1999;69:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(99)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelar R, Buchanan G, Need EF, Tilley W, Greenberg NM. Androgen receptor coregulators and their involvement in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:719–733. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linja MJ, Porkka KP, Kang Z, Savinainen KJ, Janne OA, Tammela TL, Vessella RL, Palvimo JJ, Visakorpi T. Expression of androgen receptor coregulators in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1032–1040. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan G, Irvine RA, Coetzee GA, Tilley WD. Contribution of the androgen receptor to prostate cancer predisposition and progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:207–223. doi: 10.1023/a:1015531326689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culig Z, Bartsch G. Androgen axis in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:373–381. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmann EP. Molecular biology of the androgen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3001–3015. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja SS, Ha S, Swenson NK, Torra IP, Rome S, Walden PD, Huang HY, Shapiro E, Garabedian MJ, Logan SK. ART-27, an androgen receptor coactivator regulated in prostate development and cancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13944–13952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Chen F, Melamed J, Chiriboga L, Wei J, Kong X, McLeod M, Li Y, Li CX, Feng A, Garabedian MJ, Wang Z, Roeder RG, Lee P. Distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic functions of androgen receptor cofactor p44 and association with androgen-independent prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5236–5241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712262105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongarzone I, Butti MG, Coronelli S, Borrello MG, Santoro M, Mondellini P, Pilotti S, Fusco A, Della Porta G, Pierotti MA. Frequent activation of ret protooncogene by fusion with a new activating gene in papillary thyroid carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2979–2985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh S, Chang C. Cloning and characterization of a specific coactivator, ARA70, for the androgen receptor in human prostate cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5517–5521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alen P, Claessens F, Schoenmakers E, Swinnen JV, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W, Peeters B. Interaction of the putative androgen receptor-specific coactivator ARA70/ELE1alpha with multiple steroid receptors and identification of an internally deleted ELE1beta isoform. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:117–128. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Brantley K, Bolu E, McPhaul MJ. RFG (ARA70. ELE1) interacts with the human androgen receptor in a ligand-dependent fashion, but functions only weakly as a coactivator in cotransfection assays. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1645–1656. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Minges JT, Lee LW, Wilson EM. The FXXLF motif mediates androgen receptor-specific interactions with coregulators. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10226–10235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YC, Yeh S, Yeh SD, Sampson ER, Huang J, Li P, Hsu CL, Ting HJ, Lin HK, Wang L, Kim E, Ni J, Chang C. Functional domain and motif analyses of androgen receptor coregulator ARA70 and its differential expression in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33438–33446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollara A, Kahn HJ, Marks A, Brown TJ. Loss of androgen receptor associated protein 70 (ARA70) expression in a subset of HER2-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;67:245–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1017938608460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PA, Rittenberg PV, Brown TJ. Activation of androgen receptor-associated protein 70 (ARA70) mRNA expression in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;80:132–138. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.6068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekur S, Lau KM, Long J, Burnstein K, Ho SM. Expression of RFG/ELE1alpha/ARA70 in normal and malignant prostatic epithelial cell cultures and lines: regulation by methylation and sex steroids. Mol Carcinog. 2001;30:1–13. doi: 10.1002/1098-2744(200101)30:1<1::aid-mc1008>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Yu X, Ge K, Melamed J, Roeder RG, Wang Z. Heterogeneous expression and functions of androgen receptor co-factors in primary prostate cancer. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1467–1474. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64422-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestayer C, Blanchere M, Jaubert F, Dufour B, Mowszowicz I. Expression of androgen receptor coactivators in normal and cancer prostate tissues and cultured cell lines. Prostate. 2003;56:192–200. doi: 10.1002/pros.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Li CX, Chen F, Wang Z, Ligr M, Melamed J, Wei J, Gerald W, Pagano M, Garabedian MJ, Lee P. Stimulation of prostate cancer cellular proliferation and invasion by the androgen receptor co-activator ARA70. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:225–235. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag P, Bektic J, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Eder IE. Androgen receptor down regulation by small interference RNA induces cell growth inhibition in androgen sensitive as well as in androgen independent prostate cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;96:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Snoek R, Ghaidi F, Cox ME, Rennie PS. Short hairpin RNA knockdown of the androgen receptor attenuates ligand-independent activation and delays tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10613–10620. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao X, Tang S, Thrasher JB, Griebling TL, Li B. Small-interfering RNA-induced androgen receptor silencing leads to apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:505–515. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tararova ND, Narizhneva N, Krivokrisenko V, Gudkov AV, Gurova KV. Prostate cancer cells tolerate a narrow range of androgen receptor expression and activity. Prostate. 2007;67:1801–1815. doi: 10.1002/pros.20662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosohata K, Li P, Hosohata Y, Qin J, Roeder RG, Wang Z. Purification and identification of a novel complex which is involved in androgen receptor-dependent transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7019–7029. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.7019-7029.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Miyazaki H, Lee A, Tran CP, Reiter RE. Androgen receptor and invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1128–1135. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culig Z. Re: stimulation of prostate cancer cellular proliferation and invasion by the androgen receptor co-activator ARA70. Eur Urol. 2008;53:1298. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Kokontis J, Tang F, Godfrey B, Liao S, Lin A, Chen Y, Xiang J. Androgen and its receptor promote Bax-mediated apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:1908–1916. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1908-1916.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenster G. The role of the androgen receptor in the development and progression of prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:407–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley WD, Buchanan G, Hickey TE, Bentel JM. Mutations in the androgen receptor gene are associated with progression of human prostate cancer to androgen independence. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culig Z, Hobisch A, Hittmair A, Peterziel H, Cato AC, Bartsch G, Klocker H. Expression, structure, and function of androgen receptor in advanced prostatic carcinoma. Prostate. 1998;35:63–70. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980401)35:1<63::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Wu JH, Trifiro M. The androgen receptor gene mutations database (ARDB): 2004 update. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:527–533. doi: 10.1002/humu.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin ME, Bubley GJ, Shuster TD, Frantz ME, Spooner AE, Ogata GK, Keer HN, Balk SP. Mutation of the androgen-receptor gene in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1393–1398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taplin ME, Rajeshkumar B, Halabi S, Werner CP, Woda BA, Picus J, Stadler W, Hayes DF, Kantoff PW, Vogelzang NJ, Small EJ. Androgen receptor mutations in androgen-independent prostate cancer: cancer and Leukemia Group B Study 9663. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2673–2678. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duff J, McEwan IJ. Mutation of histidine 874 in the androgen receptor ligand-binding domain leads to promiscuous ligand activation and altered p160 coactivator interactions. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2943–2954. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Cavasotto CN, Cardozo T, Ha S, Dang T, Taneja SS, Logan SK, Garabedian MJ. Androgen receptor mutations identified in prostate cancer and androgen insensitivity syndrome display aberrant ART-27 coactivator function. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2273–2282. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Shi Y, Xu LL, Nageswararao C, Davis LD, Segawa T, Dobi A, McLeod DG, Srivastava S. Androgen receptor mutation (T877A) promotes prostate cancer cell growth and cell survival. Oncogene. 2006;25:3905–3913. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazi J, Bakkour N, Stamm S. Alternative splicing and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotheim RI, Nees M. Alternative splicing in cancer: noise, functional, or systematic? Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:1432–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebrow A, Kornblihtt AR. The connection between splicing and cancer. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2635–2641. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables JP. Aberrant and alternative splicing in cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7647–7654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnina Z, Zayakin P, Silina K, Line A. Alterations of pre- mRNA splicing in cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2005;42:342–357. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narla G, DiFeo A, Yao S, Banno A, Hod E, Reeves HL, Qiao RF, Camacho-Vanegas O, Levine A, Kirschenbaum A, Chan AM, Friedman SL, Martignetti JA. Targeted inhibition of the KLF6 splice variant. KLF6 SV1, suppresses prostate cancer cell growth and spread. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5761–5768. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]