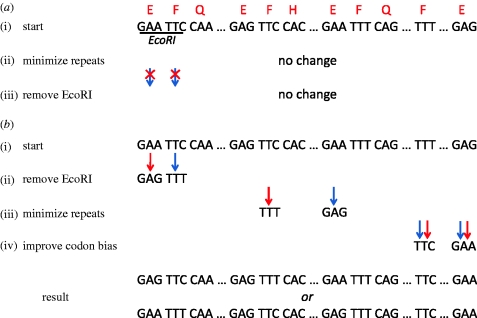

Figure 2.

Choosing an appropriate design algorithm. A simple example is shown of how two different algorithms for the same optimization problem are affected by sequence constraints. The coding sequence encodes five peptide segments of a protein, which may or may not be contiguous. The initial starting sequence is one possibility, chosen to match the target codon bias of the gene. The optimization constraints for both algorithms are that (i) no EcoRI is allowed, (ii) codon usage ratios for E (GAG/GAA) and F (TTC/TTT) must be equal to 1, and (iii) direct sequence repeats greater than seven nucleotides should be minimized. Iterations involve single codon replacements and a greedy search is followed. Thus, replacements are allowed only if improvement is achieved. At each step, no worsening of previously applied constraints is allowed. The algorithm in (a) begins by minimizing repeat elements and then tries to remove EcoRI sites without increasing the number of repeats. Since either possible substitution to remove the EcoRI site will add new repeats, no change is allowed and the algorithm fails to reach its goals. In (b), because the hard constraint of restriction site removal is applied first, the algorithm has two routes (red versus blue arrows) to successfully reach the goals.