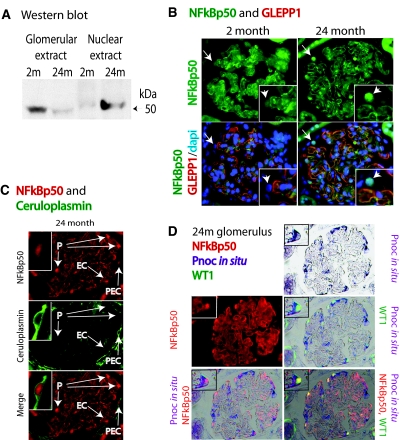

Figure 4.

NFκB p50 is translocated to nuclei in old glomeruli. (A) Western blot showing that whole-glomerular extracts had less NFκB p50 protein identified in old versus young glomeruli when equal amounts of protein were loaded. In contrast, the nuclear extracts of old glomeruli had increased detectable NFκB p50 protein when equal amounts of protein were loaded. (B) Immunofluorescent photomicrographs showing enhanced NFκB p50 (green) presence in glomerular nuclei of 24-month compared with 2-month rats (inset). The glomerular architecture is illustrated by double-label staining with GLEPP1 (red) to demonstrate podocyte foot process distribution along glomerular capillary loops. The arrows indicate podocyte nuclei identified on the glomerular surface based on GLEPP1 (red) and DAPI (blue) which also express NFκB p50 (green) in 24-month but not 2-month glomeruli. (C) A 24-month glomerulus showing nuclear NFκB p50 (red) staining in podocyte nuclei (P), a parietal epithelial cell nucleus (PEC), and a probable endothelial cell nucleus (EC) on the basis of its location within the capillary loop. Double-label staining of ceruloplasmin (green) of parietal epithelial cell cytoplasm demonstrates that the ceruloplasmin-containing cell also has an NFκB-stained nucleus (see inset). (D) A 24-month glomerulus demonstrating that the podocytes identified by having WT1-positive nuclei (green) also contain nuclear NFκB p50 protein (red) and are the same cells that express Pnoc mRNA as detected by in situ hybridization (purple). The insets demonstrate triple labeling of a podocyte to emphasize this point. m, month; dapi, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. All photomicrograph images were made at ×200 magnification.