In this communication we will discuss three questions about orthotopic liver transplantation (liver replacement). First, what are the indications for hepatic transplantation? Second, what have been the results? Third, what is the outlook for improving these figures?

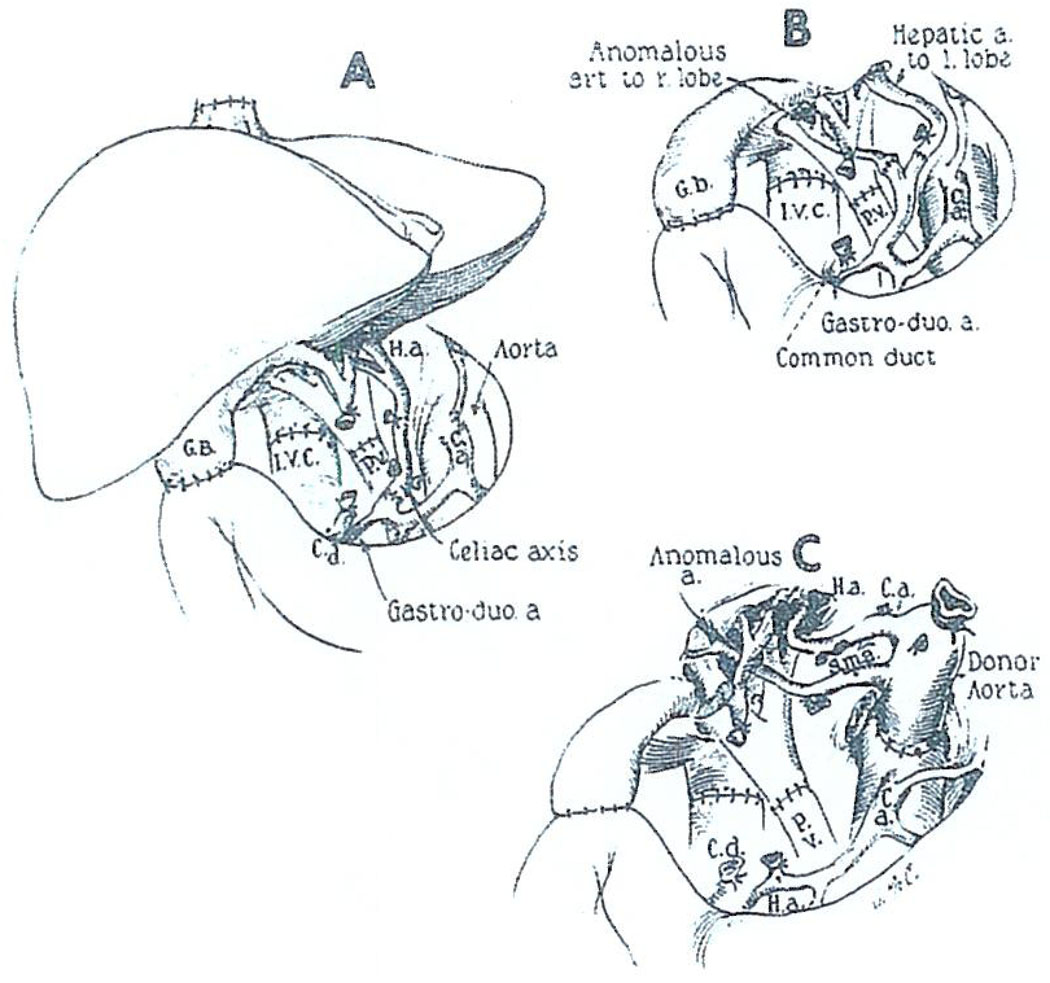

Orthotopic liver transplantation is often difficult, mainly because of the liver pathology that essentially always creates severe portal hypertension and extensive venous collaterals. Thus, removal of the native liver may be an extremely formidable undertaking. Revascularization of the graft is performed in as anatomically normal a way as possible: anastomosing the portal vein and hepatic artery end-to-end and reconstructing the vena cava above and below the liver (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Orthotopic liver transplantation: the recipient operation. In most recent cases, cholecystoduodenostomy has been performed for biliary drainage as shown. C.a., celiac axis; C.d., common duct; G.B., gallbladder; H.a., hepatic artery; I.V.C., inferior vena cava; P.V., portal vein; S.m.a., superior mesenteric artery. (A) The kind of arterial anastomosis most commonly used. The homograft celiac axis or common hepatic artery is attached to the proper or common hepatic artery of the recipient. (B) Arterial reconstruction of two homograft arteries. The vessels are individually anastomosed to the branches of the recipient proper hepatic artery. (C) Anastomosis of the homograft aorta to the recipient aorta. The variation was used in a 16-mo-old recipient because of the double arterial supply to the transplanted liver. (With permission of Ann. Surg. 168:392, 1968.)

By far the most unsatisfactory aspect of this operation has been bilary duct reconstruction. In most of our cases, we have anastomosed the gallbladder to the duodenum after ligating the distal common duct. This method has real advantages under conditions of immunosuppression because it can be performed without stents and drains. However, there have been a number of lethal complications with these cholecystoduodenostomies, a point to which we will return later.

INDICATIONS FOR ORTHOTOPIC TRANSPLANTATION

Hepatic Malignancy

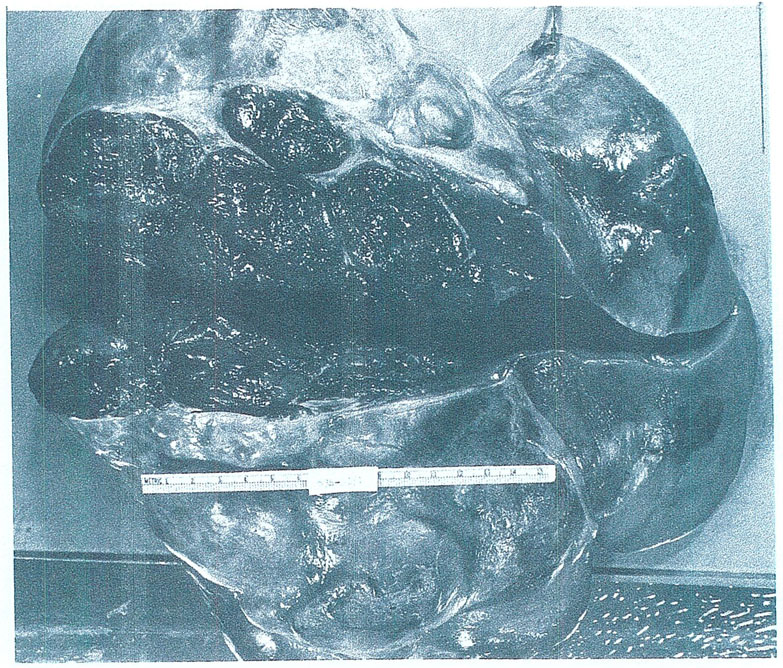

At the beginning, we thought that the ideal reason for liver replacement would be primary hepatic malignancies, including hepatoma. An example of the kind of extensive hepatoma we treated in the early trials is shown in Fig. 2. Our enthusiasm was quickly dampened by a repetitive experience which can be illustrated with a single case.

Fig. 2.

The hepatoma and remaining liver excised from a 29-yr-old woman at the time of orthotopic transplantation. The operative specimen weighed 10 kg. (With permission.5)

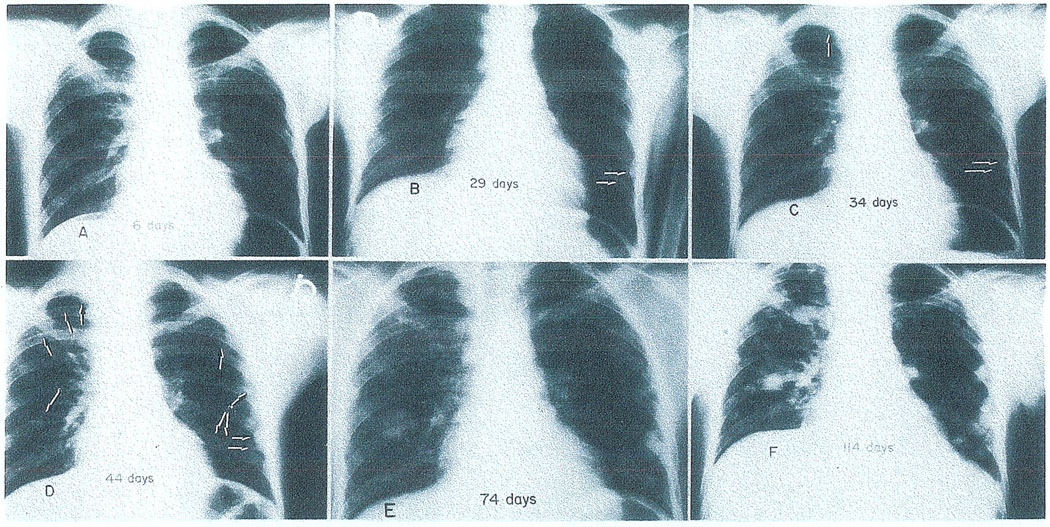

In Fig. 3 is the chest X-ray of a 15-yr-old boy a few weeks after successful orthotopic liver transplantation for a gigantic hepatoma, by which time there was already a small pulmonary metastasis at 29 days. He died 143 days after operation with his lungs almost replaced by metastases. During the same interval, his new liver was similarly invaded as could be followed with serial scans (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The extremely rapid development of pulmonary metastases in a patient whose indication for liver replacement was hepatoma. (A) The chest is clear 6 days after transplantation. (B) Twenty-nine days postoperative. Two metastases are visible in the lower left lung field (arrows). (C) Five days later the tumor deposits previously seen have grown in size (horizontal arrows) and a third focus is now present in the right upper lobe (vertical arrow). (D) Forty-four days; only 10 days have elapsed since the last examination. Metastatic growths are scattered throughout the lungs (arrows). (E) Seventy-four days postoperative. (F) Four months after operation; transient dyspnea was first noticed a few days later. The patient died of pulmonary insufficiency 143 days after transplantation. (With permission.5)

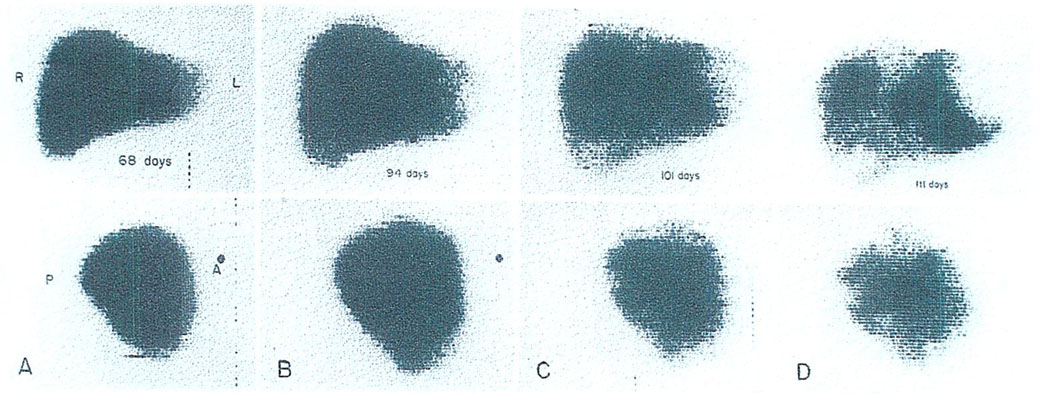

Fig. 4.

Destruction of a hepatic homograft by tumor recurrence, as demonstrated by serial technetium liver scans. (A) Sixty-eight days: the scan appears normal. (B) Ninety-four days: the patient had become jaundiced. Hepatomegaly is evident. (C) One hundred one days: multiple areas of poor isotope concentration are now visible. (D) One hundred eleven days: the process has continued its rapid progression. By the time of death 1 mo later, the homograft was almost completely replaced by tumor. (With permission.5)

With the destruction of his liver he became secondarily jaundiced (Fig. 5) and finally died of combined hepatic and pulmonary insufficiency. At autopsy, his lungs were a mass of tumor. The same was true of the transplanted liver to an extent that only a remnant of normal hepatic tissue remained. We have six other so-called successful liver transplantations with subsequent widespread metastases and, in fact, three of our patients died at or beyond 1-yr posttransplantation of this complication.

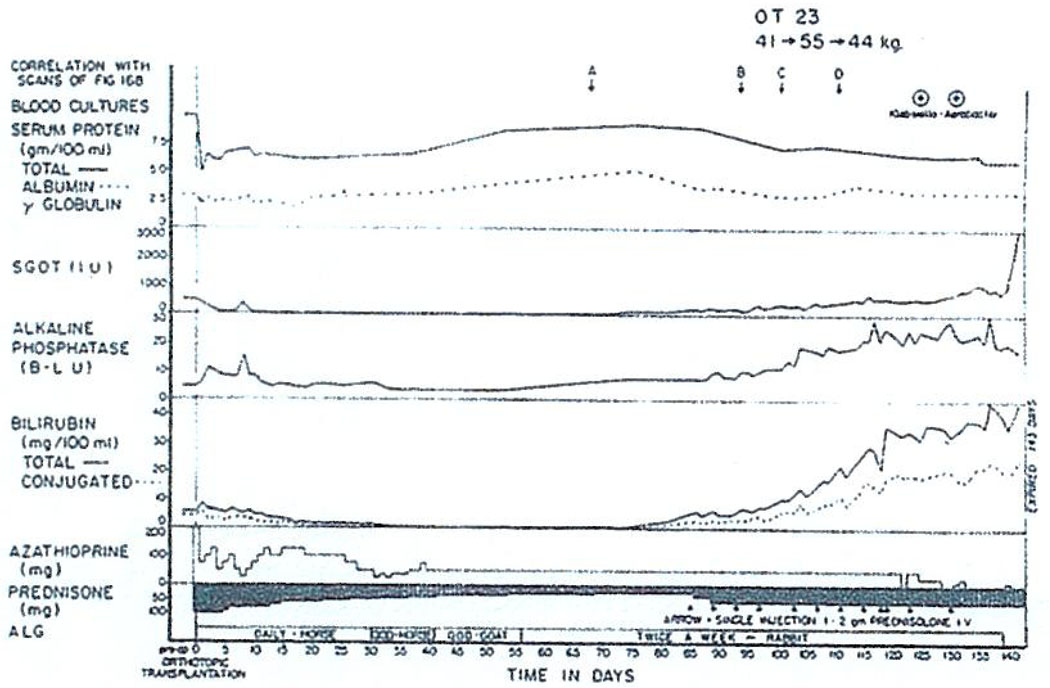

Fig. 5.

The manifestations of the invasion and nearly complete destruction of an orthotopic liver homograft by recurrent hepatoma. The sporadic large doses of intravenous prednisolone were given because of the possibility that the deteriorating liver function was due to delayed rejection. At autopsy almost all the transplanted hepatic tissue was replaced by tumor. The liver scans of this patient shown in Fig. 4 are indicated by the lettered arrows (A–D). The normal range for Bessey–Lowry (B–L) alkaline phosphatase units is 1–3. The normals for the SGOT and SGPT units at this age are 60–100 and 5–35, respectively. (With permission.5)

It is too early to conclude once and for all that liver transplantation cannot be used to treat hepatoma. This can also be illustrated by another case. Pictured in Fig. 6 is the liver of a child with biliary atresia in which was found a small 2 cm hepatoma as an incidental pathologic feature. The child has a perfect result without evidence of tumor recurrence more than 2 yr later. Long survival after liver replacement in patients with hepatoma has also been reported by Calne, Daloze, and Fortner.1–3 Nevertheless, we personally would prefer not to do more hepatomas at this time because of the very high incidence of metastases exceeding 80%.

Fig. 6.

The liver removed from a child with biliary atresia at the time of orthotopic hepatic transplantation. Note the 2 cm hepatoma, an incidental finding in the specimen.

It has seemed possible that the outlook might be less gloomy if the malignant tumor were some kind other than a hepatoma. For example, cholangiocarcinomas might provide a reasonable indication. Then there are the rare neoplasms, of which the gross specimen in Fig. 7 is an example, with widespread multifocal primaries. This liver was taken from a 52-yr-old man who had a hemangioendothelial sarcoma. The neoplasm usually kills within a few weeks by intraabdominal hemorrhage or the development of hepatic insufficiency rather than by spread. In the summer of 1971, we treated the patient with orthotopic liver transplantation. The histopathologic character of the growth showed nearly normal hepatic cells and malignant Kupffer cells.

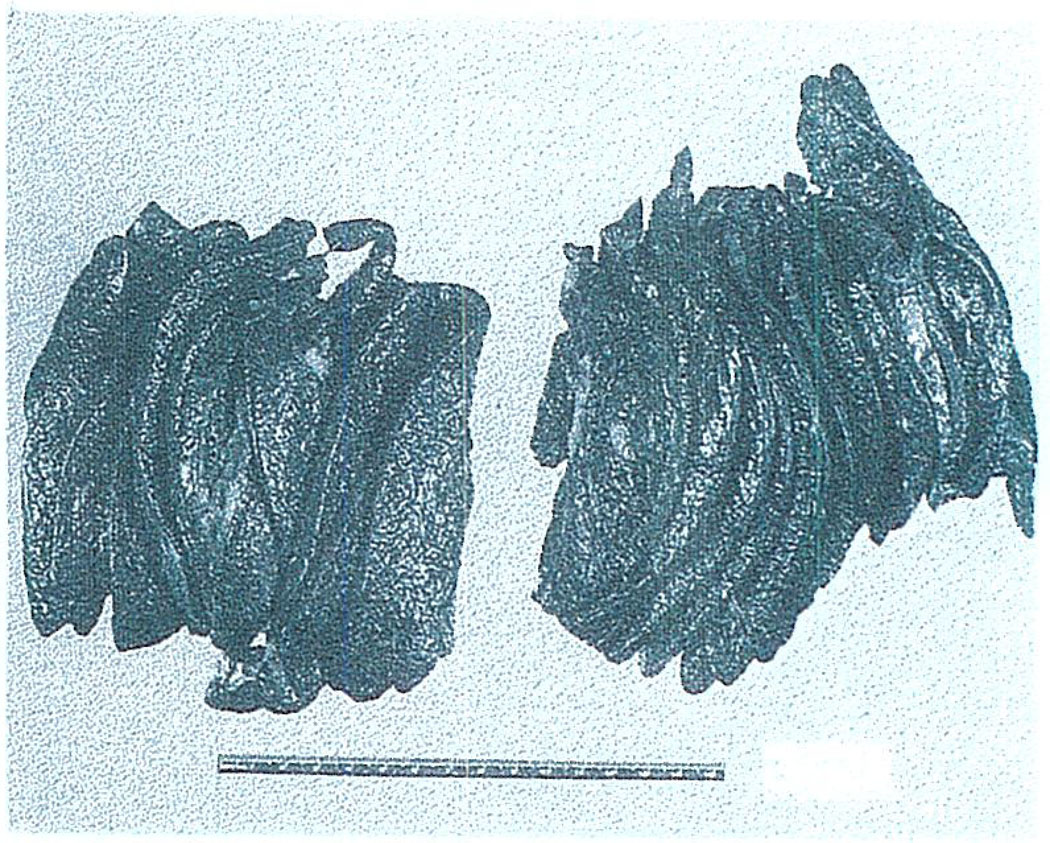

Fig. 7.

Macroscopic appearance of the liver excised at the time of hepatic transplantation for the indication of hemangioendotheliai sarcoma.

Postoperatively, the bilirubin fell from 40 to nearly normal along with an improvement in other liver functions (Fig. 8). The patient survived a severe rejection which was eventually completely reversed. After achieving nearly normal function for more than 3 mo, this patient also developed widespread pulmonary metastases, as well as extensive recurrence in his liver graft. Thus, here is one more example of the futility of treating hepatic malignancy with hepatic transplantation.

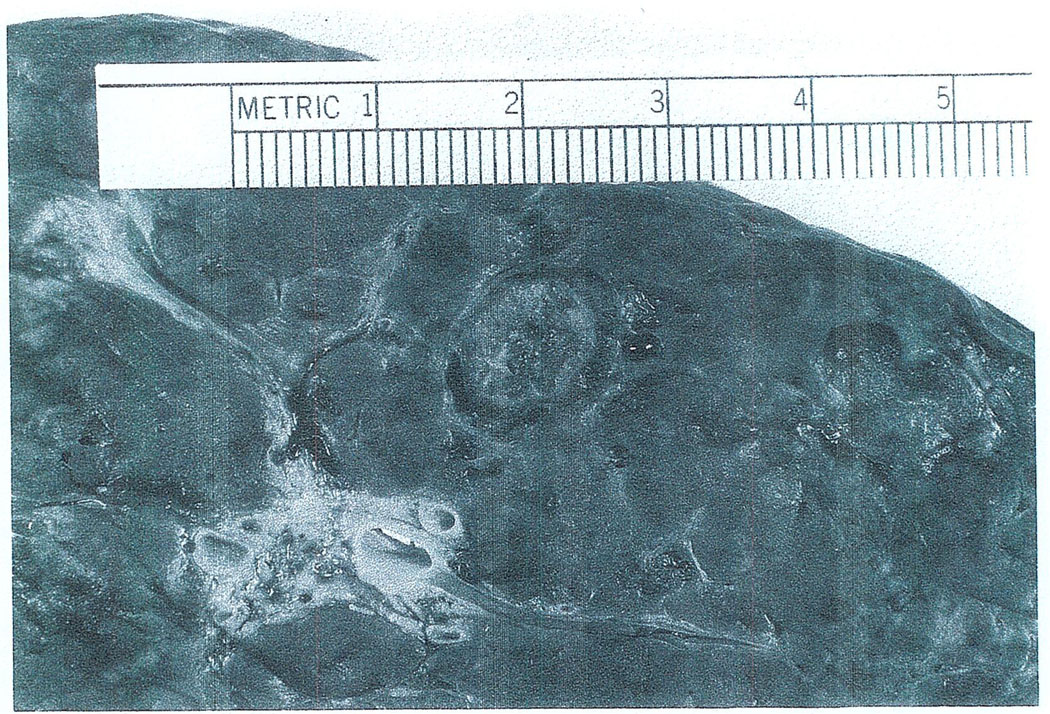

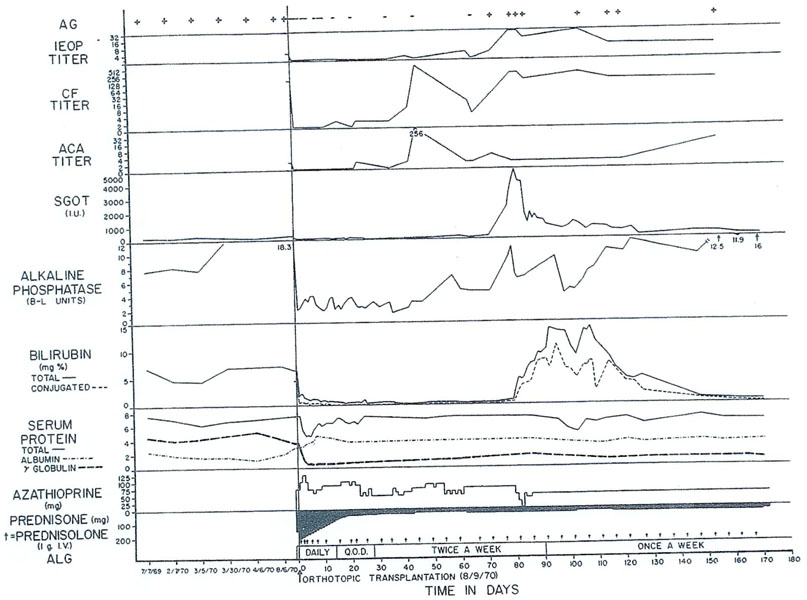

Fig. 8.

The early course of a 52-yr-old male who had total liver replacement as treatment for a hemangioendothelial sarcoma. This rare liver tumor usually causes death from fulminating hepatic failure in a few weeks or months, but it does not commonly metastasize. After transplantation, there was a severe rejection crisis. The protracted thrombocytopenia post-operatively is often noted after liver transplantation and is probably due to thrombocyte sequestration in the homograft. ALG, horse antilymphocyte globulin; SGOT, serum glutamic oxalacetic transaminase in international units; and ARROW—625 milligrams of methyl prednisolone intravenously. (With permission.6)

In this last case, one of the immunosuppressive agents used was cyclophosphamide rather than azathioprine (Fig. 8). Cyclophosphamide is, itself, one of the most widely used of the anticancer chemotherapeutic drugs. It is also one of the best immunosuppressants. In addition, heterologous ALG and prednisone were used.

Benign Hepatic Disease

Beginning in such a negative way about the indications for liver replacement is one way of indicating that the important future of hepatic transplantation is in the treatment of nonneoplastic hepatic disease. There is little point in listing these diseases since the end-stage is much the same in all. In fact, our general position now is that anyone under age 40 who is not a sociopath and who is dying of hepatic insufficiency should theoretically be a candidate for liver transplantation. The most common diagnoses would, of course, be cirrhosis, chronic aggressive hepatitis, and biliary atresia.

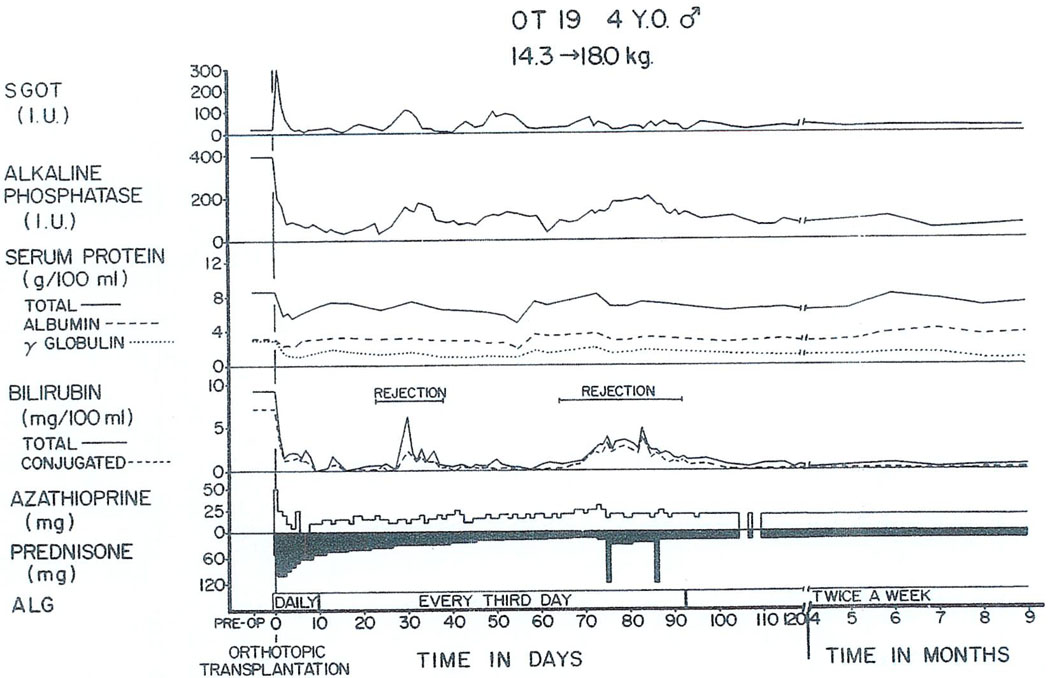

To date, the longest survivor in the world after liver transplantation was a boy whose operation was in July 1968, for biliary atresia. His early course is shown in Fig. 9. There was a very minimal rejection crisis in the second postoperative month. His liver was biopsied at 3 yr and found to be almost normal. Then suddenly just before Christmas 1971, he developed massive liver necrosis and died of acute hepatic insufficiency a few days later after a total survival of 3.5 yr, of which almost all was spent in good health.

Fig. 9.

The early course of a 4-yr-old child who survived for 3.5 years after orthotopic liver transplantation for the indication of biliary atresia. Note the rejection episodes at 1 mo and 2.5 mo, which were easily controlled. (With permission.5)

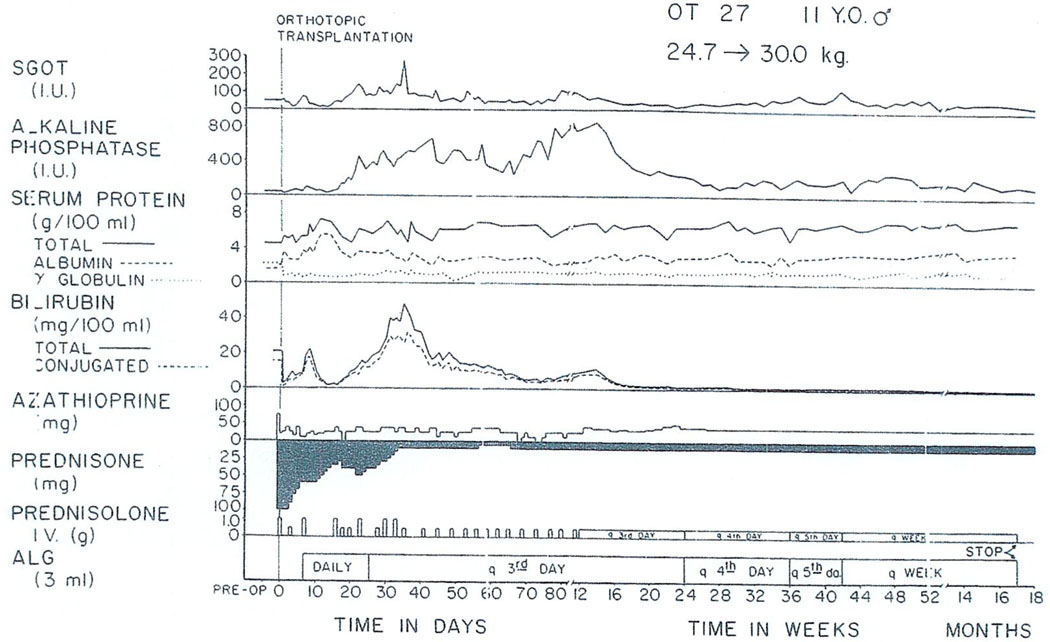

The liver of another patient with benign disease is shown in Fig. 10. This child was suffering from Wilson’s disease, which led to cirrhosis and finally profound liver failure. After operation, he had a grave rejection crisis (Fig. 11) which eventually reversed with an ultimately good result now after almost 3 yr. He has returned to his home in Ohio where he now goes to school.

Fig. 10.

The native liver of a child whose hepatic failure was caused by Wilson’s disease. The recipient’s postoperative course is shown in Fig. 11.

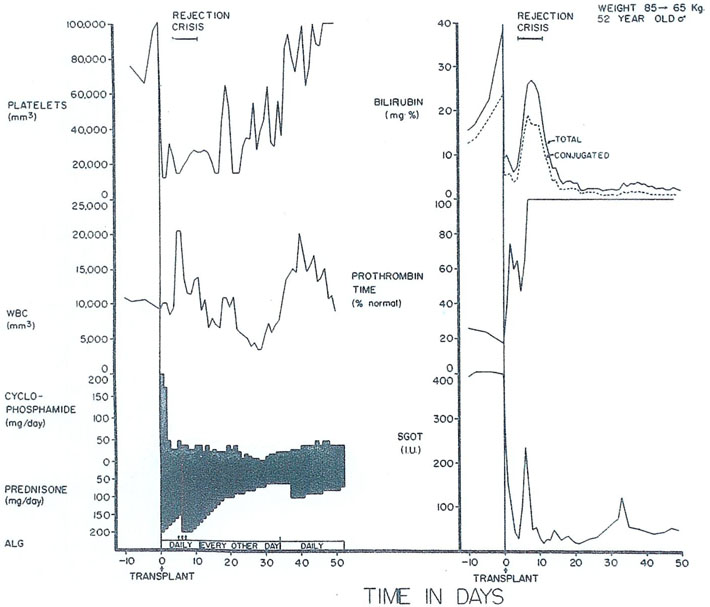

Fig. 11.

Postoperative course of an 11-yr-old recipient of an orthotopic liver homograft for cirrhosis secondary to Wilson’s disease. A severe rejection crisis beginning about 3 wk posttransplantation eventually reversed and hepatic function has been essentially normal since the sixth postoperative month. The patient remains in good health almost 3 yr after operation.

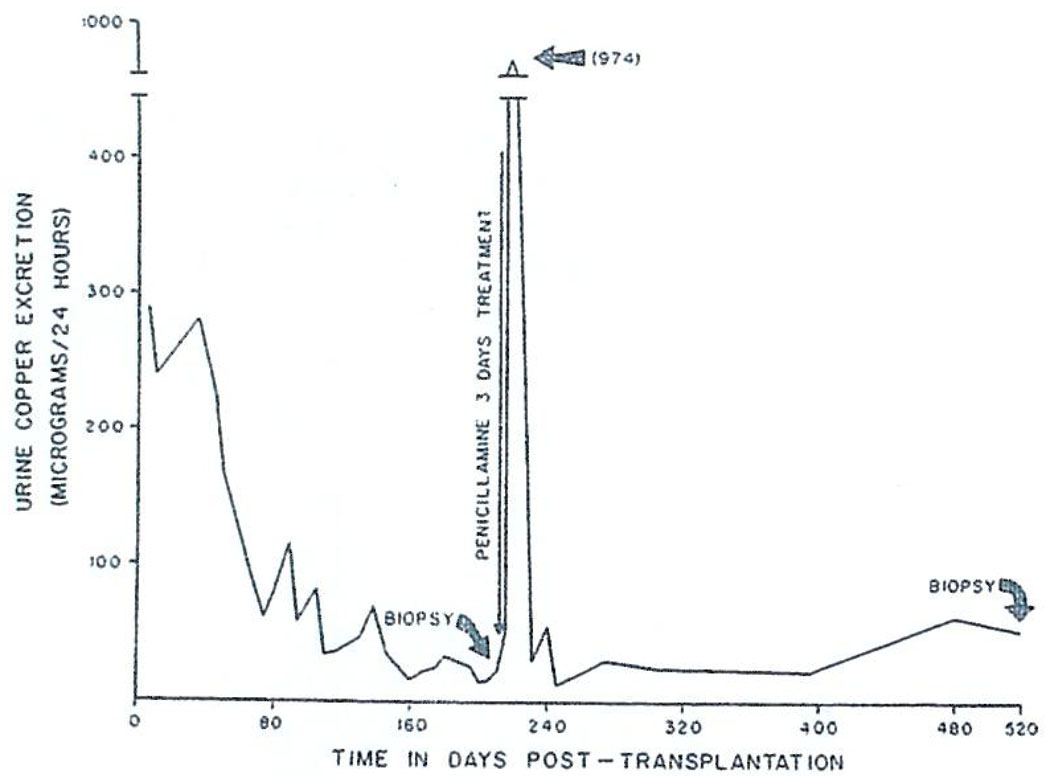

Wilson’s disease is an inborn error of metabolism of which the precise pathophysiology has never been worked out. The essential biochemical finding is the deposition of copper in all tissues, including the liver and brain. The characteristic Kayser–Fleischer rings by which the ophthalmologist can make the diagnosis are nothing more than copper accumulations in the cornea. The information we have about this case makes us believe that this copper accumulation is not recurring posttransplantation and that, on the contrary, copper metabolism is probably remaining relatively normal. After operation, there was a massive cupriuresis which lasted for almost 6 mo. (Fig. 12). At this time, the liver was biopsied and then biopsies were repeated after 1.5 and 2.5 yr. On both occasions the liver copper content was normal.

Fig. 12.

Urinary excretion of copper after orthotopic liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease. Following operation there was a massive cupriuresis lasting 6 mo. A secondary peak of copper excretion occurred in response to a 3-day test course of penicillamine. (With permission, Lancet 1:505, 1971).

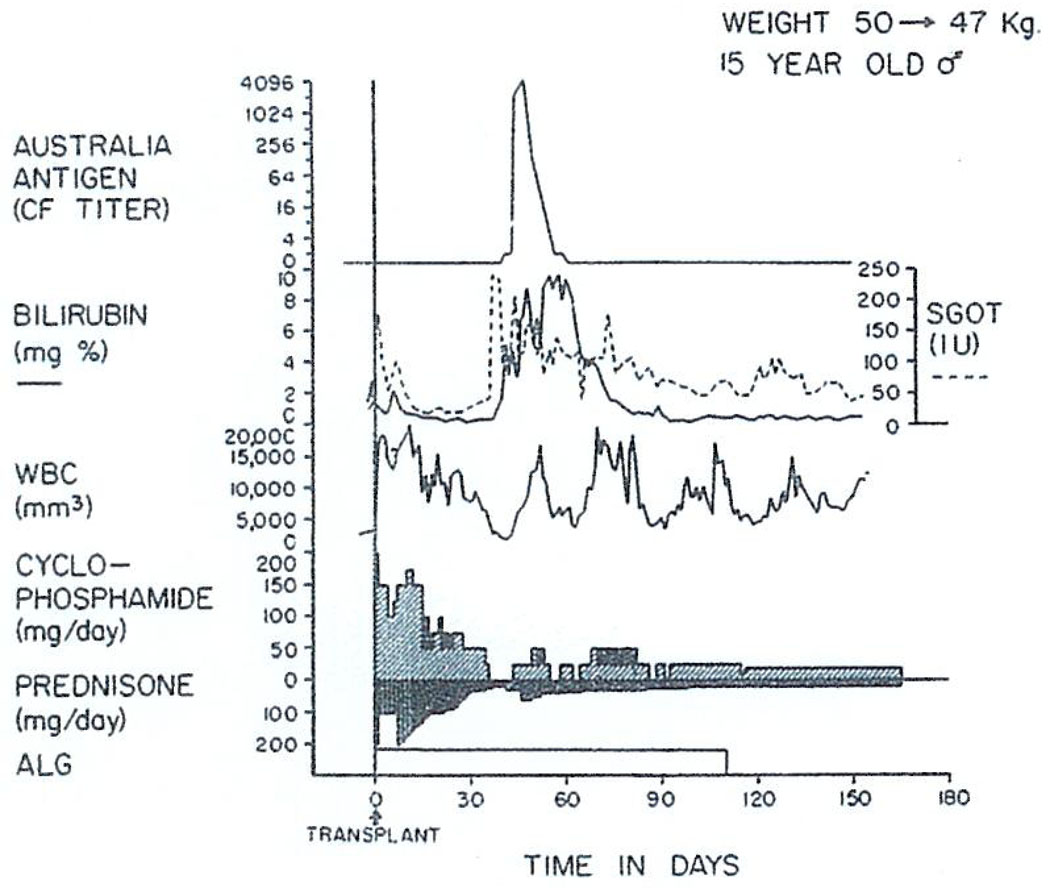

We treated another patient with Wilson’s disease 15 mo ago. In this patient the main indication for proceeding was extremely severe neurologic involvement that was not controlled by penicillamine therapy. The immunosuppressive treatment was with cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) instead of azathioprine (Imuran); in addition to the cyclophosphamide, horse ALG and prednisone were administered. Rejection probably never occurred in this patient. There was a marked deterioration of hepatic function in the second postoperative month at which time jaundice developed with rises in transaminases. At the same time, he developed Australia antigenemia with prodigious increases in his complement fixation titers. Immunosuppression was not intensified and he spontaneously recovered. The reason for mentioning this second point is that we now realize how many factors other than rejection can cause deterioration of hepatic homograft function. The most important of these nonimmunologic complications are serum hepatitis, such as demonstrated in Fig. 13, biliary duct obstruction, which we will return to later since it is a dreaded complication, and drug-induced hepatotoxicity.

Fig. 13.

Triple drug therapy with cyclophosphamide, prednisone and horse antilymphocyte globulin (ALG) in a patient who had an orthotopic liver transplantation for Wilson’s disease. Rejection has never been diagnosed postoperatively. The temporary deterioration in hepatic function in the second postoperative month was accompanied by Australia antigenemia detected by the complement fixation (CF) technique and consequently was thought to be a manifestation of serum hepatitis. (With permission.6)

This concludes our remarks about indications, which can be summarized with one sentence. We believe the situation is completely analogous to that in renal transplantation in which field benign disease is also the prime indication for treatment.

CLINICAL RESULTS

Between Spring 1963 and July 1967, seven attempts at orthotopic liver transplantation were made in Denver. All failed, with death in 21 days or less. Our own experience, including these cases and all subsequent ones until a little more than 1 yr ago, has consisted of 42 cases. Survival of 1 yr or more was obtained in 11 of these 42 recipients (26%). The record was not disgraceful since all these patients were doomed to early death, but it can certainly stand improvement.

A year or more after transplantation, eight patients were lost for the reasons and at the times indicated in Table 1. The most common causes of late failure were carcinomatosis and chronic rejection, accounting for three deaths each after 1 yr. Serum hepatitis (chronic aggressive variety) caused two late deaths.

Table 1.

Eleven One-Year Survivors After Orthotopic Transplantation

| Alive 3/11:1-1/6–2-5/6 yr |

| Died 8/11:1–3½ yr |

| 12 mo: Cancer* |

| 12 mo: Serum hepatitis, liver failure |

| 14 mo: Cancer |

| 15 mo: Cancer |

| 15 mo: Rejection, liver failure |

| 20 mo: Nocardia infection, systemic† |

| 30 mo: Rejection, liver failure |

| 42 mo: ? Rejection, liver failure |

This patient actually died a few days short of one year.

The homograft had not failed but had advanced chronic aggressive hepatitis, just as in her previously removed native kidney.

The whole question of serum hepatitis in transplant patients is just beginning to unfold but it is already established that it is a potentially serious matter. Liver disease and, specifically, hepatitis in renal transplant patients is a very common complication, occurring in 10%–20% of all kidney recipients in our center. The incidence of serum hepatitis in our liver patients is even higher, and one example of this has already been demonstrated (Fig. 13). In view of these observations, is there any hope of treating lethal serum hepatitis with liver transplantation? We do not know the answer to the question. However, it is worth telling of an extraordinary patient whose reason for transplantation was chronic aggressive hepatitis, Australia-antigen positive. She was in profound hepatic failure.

Transplantation was carried out on August 6, 1970. The Australia antigen became negative for almost 2 mo and then returned to positive at the same time as a clinical bout of acute serum hepatitis (Fig. 14). She recovered from this but her Australia antigen has remained positive to the present. A repeat biopsy 14 mo after transplantation revealed recurrence of the chronic aggressive hepatitis in her transplanted liver. She died of a Nocardia infection on April 21, 1972. Her homograft was the site of advanced chronic aggressive hepatitis. Nevertheless, meaningful life was prolonged and, in view of this, the issue of whether more similar patients should be treated is perhaps more of a philosophical than a medical one.

Fig. 14.

Orthotopic hepatic transplantation for liver failure caused by chronic aggressive hepatitis. The Australia antigen, which had been detectable in multiple serum samples for 1 yr before operation, disappeared within hours after removal of her own liver. However, the Au antigen reappeared in her blood stream about 2 mo posttransplantation at a time when she developed a clinical episode of hepatitis.

FUTURE PROSPECTS

The third question posed at the outset concerned the prospects of improving the outlook after liver replacement, assuming that only reasonable candidates with non-malignant disease are accepted. One of the real weaknesses in this procedure is ineffective reconstruction of the biliary duct.

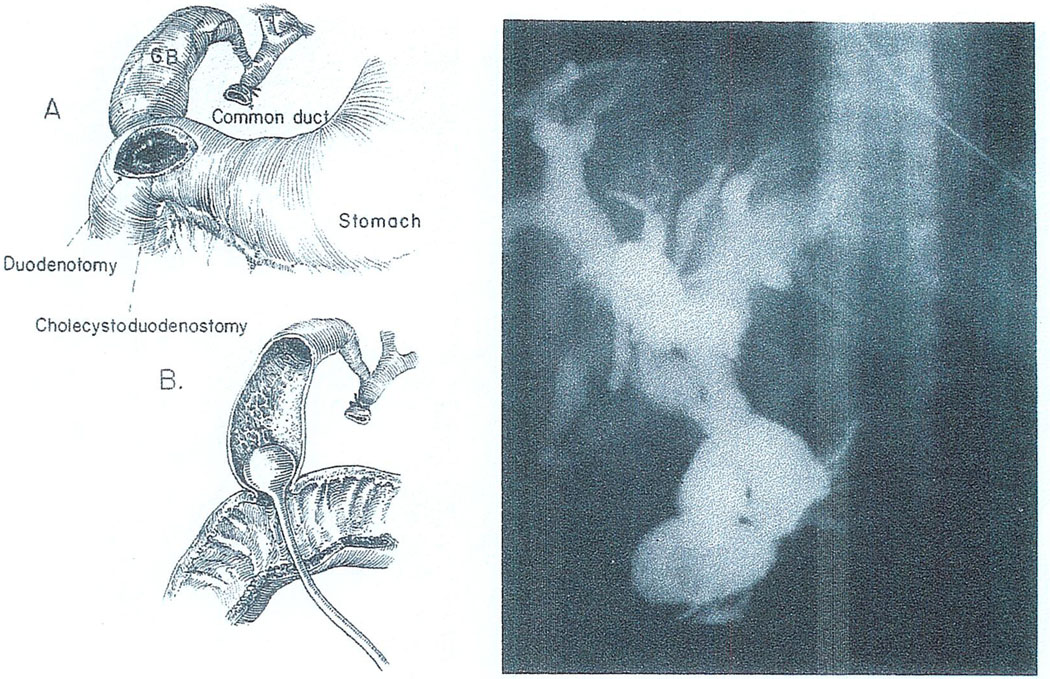

With cholecystoduodenostomy, we have had obstruction at or near the junction of the common and cystic ducts. The nature of the lesion can be appreciated by the kind of operative cholangiogram that is performed with a Foley catheter inserted into the gallbladder (Fig. 15). The obstruction of the duct system shown in Fig. 15 was corrected in two cases at reoperation but too late. All four of the patients with this lesion died.

Fig. 15.

Cholangiography of a hepatic homograft in which biliary reconstruction was with cholecystoduodenostomy. Left: Technique of dye injection through a duodenotomy and the anastomosis. Right: Obstructed duct system. Despite reexploration and conversion to choledochoduodenostomy, the recipient died of uncontrolled sepsis 46 days after transplantation.

A crucial question in cases like that just described is the reason for obstruction at or near the cystic duct. In four recent cases of this kind in which specimens became available for histopathologic examination, Dr. K. A. Porter of London has made some intriguing observations. He found that the extrahepatic ducts had ulcerations and edema even though there was little or no evidence of active rejection. The epithelial cells of these ducts were swollen and had intranuclear inclusions resembling those of cytomegalovirus (CMV). Thus, the very real possibility has to be kept open that this variety of biliary duct obstruction has an infectious etiology.

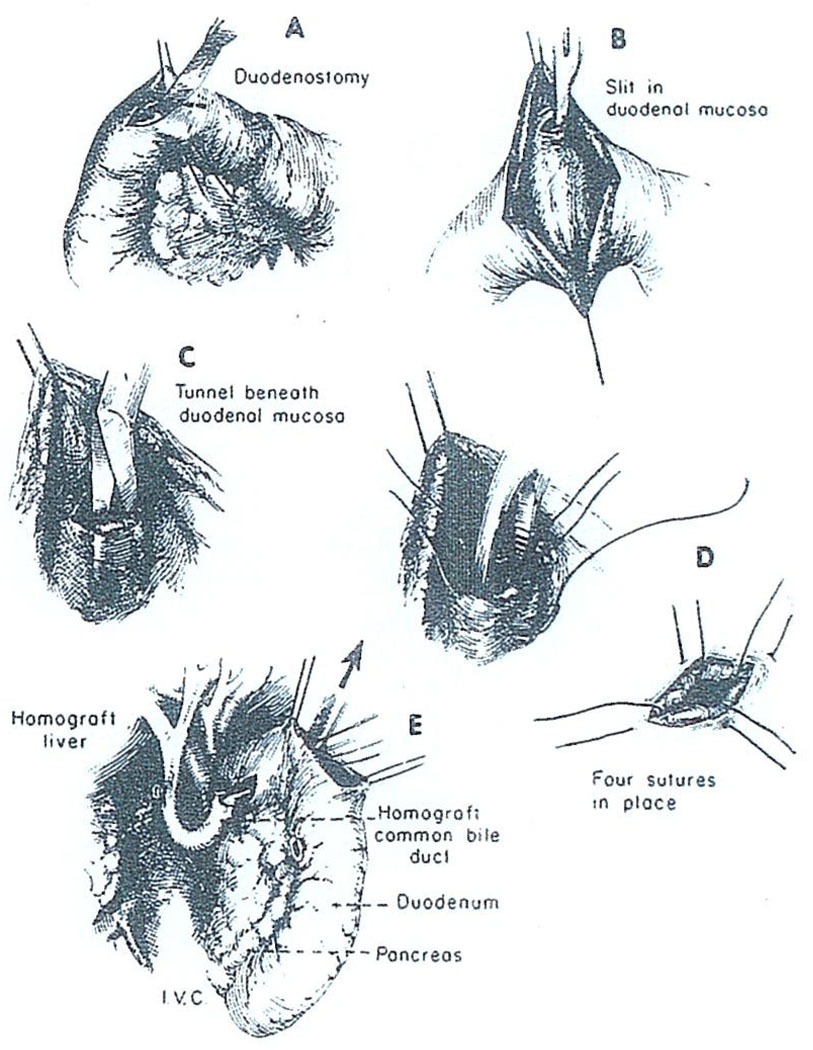

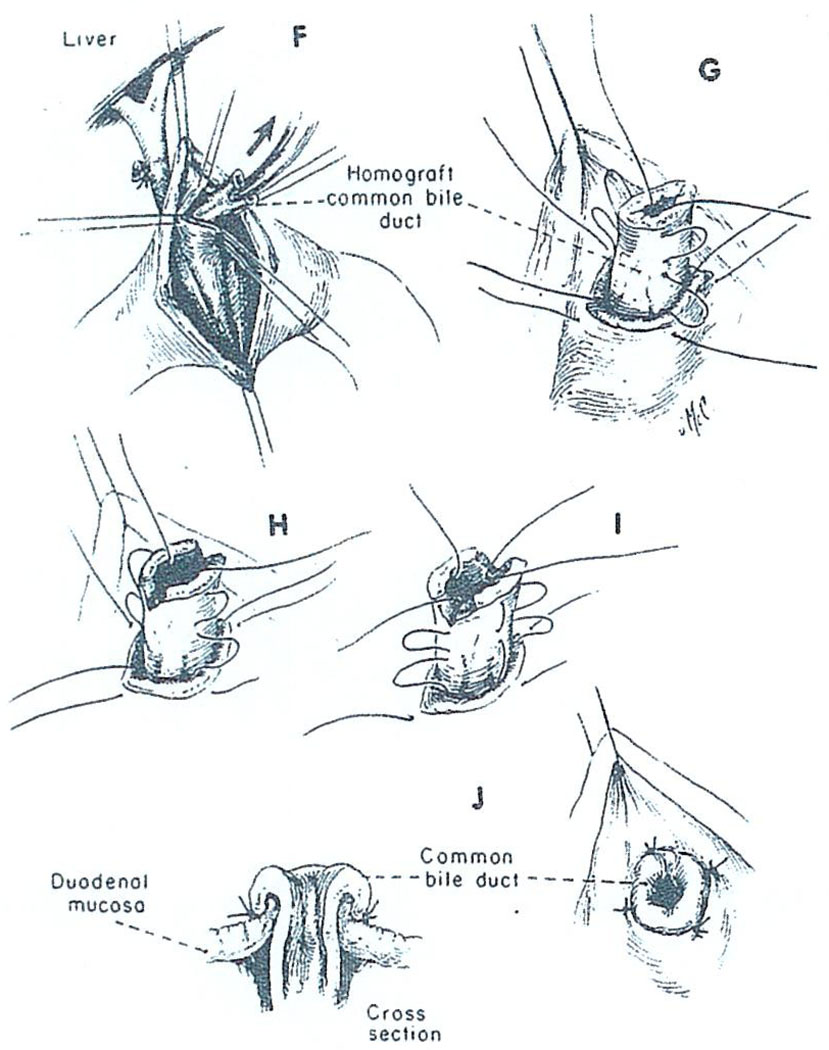

Whatever its cause, it is possible that this kind of biliary obstruction could be avoided if the small caliber cystic duct were not made part of the conduit for bile drainage. In four recent cases of liver transplantation, we have performed choledochoduodenostomy by the technique shown in Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 in which the common duct is passed through a short duodenal tunnel and then everted with a few sutures. Unfortunately, one of these patients died after disruption of the choledochoduodenostomy and the development of biliary peritonitis. As a consequence of this sad experience we have again reversed ourselves and are inclined to perform cholecystoduodenostomy as a primary procedure. However, we would promptly reexplore with the slightest suspicion of mechanical obstruction and then convert to the type of anastomosis shown in Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 or to some other alternative reconstruction.

Fig. 16.

Technique of choledochoduodenostomy. After opening the duodenum (A), a submucosal tunnel is created (B, C) through which the homograft common bile duct is passed (E).

Fig. 17.

Choledochoduodenostomy (continued). The homograft bile duct is secured in place with four fine sutures (G, H, I) in such a way as to create an everting nipple (J).

In addition to improving the technical performance of liver transplantation, we believe it is important to try to use immunosuppressive agents that have low hepatotoxicity and with this objective we have switched since early last year to cyclophosphamide instead of azathioprine for all our fresh cases. The usefulness of this major change will require much more evaluation before it can be generally recommended. However, we would like to tell you now that our primary treatment in the next cases will be with cyclophosphamide, prednisone and, ALG. After 3–8 wk, we will then switch from cyclophosphamide to maintenance azathioprine. This switch-over technique has already had an extensive and highly satisfactory evaluation after human renal transplantation.

SUMMARY

A brief answer will now be given to each of the three questions posed at the beginning. First, the prime indication for liver replacement is nonneoplastic hepatic disease. Second, the 1-yr survival in our clinic for all patients treated up to 1 yr ago was between 25% and 30%. Third, there should be considerable optimism that this survival can be improved by a better technical performance and especially by improved biliary duct drainage. Some recent developments in immunosuppression in which cyclophosphamide has been used to replace or supplement azathioprine may also be beneficial.

Acknowledgments

Supported by research grants from the Veterans Administration, by Grants RR-00051 and RR-00069 from the general clinical research centers program of the Division of Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, and by USPHS Grants AI-10176-01, AI-AM-08898, AM-07772, and HE-09110.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calne R, Williams R. Br. Med. J. 1970;3:436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5720.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daloze PM. Union Med. Can. 1971;100:68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortner JG, Beattie EJ, Jr, Shiu MH, Kawano N, Howland WS. Ann. Surg. 1970;172:23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martineau G, Porter KA, Corman J, Launois B, Schroter GT, Palmer W, Putnam CW, Groth CG, Halgrimson CG, Penn I, Starzl TE. Surgery. 1972;72:604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starzl TE, Putnam CW. Experience in Hepatic Transplantation. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starzl TE, Putnam CW, Halgrimson CG, Schroter GT, Martineau G, Launois B, Corman JL, Penn I, Booth AS, Jr, Groth CG, Porter KA. Surg. Gynec. Obstet. 1971;133:981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]