Abstract

We performed a second-generation genome wide association study of 4,533 celiac disease cases and 10,750 controls. We genotyped 113 selected SNPs with PGWAS<10−4, and 18 SNPs from 14 known loci, in a further 4,918 cases and 5,684 controls. Variants from 13 new regions reached genome wide significance (Pcombined<5×10−8), most contain immune function genes (BACH2, CCR4, CD80, CIITA/SOCS1/CLEC16A, ICOSLG, ZMIZ1) with ETS1, RUNX3, THEMIS and TNFRSF14 playing key roles in thymic T cell selection. A further 13 regions had suggestive association evidence. In an expression quantitative trait meta-analysis of 1,469 whole blood samples, 20 of 38 (52.6%) tested loci had celiac risk variants correlated (P<0.0028, FDR 5%) with cis gene expression.

Celiac disease is a common heritable chronic inflammatory condition of the small intestine induced by dietary wheat, rye and barley, as well as other unidentified environmental factors, in susceptible individuals. Specific HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 risk alleles are necessary, but not sufficient, for disease development1,2. The well defined role of HLA-DQ heterodimers, encoded by these alleles, is to present cereal peptides to CD4+ T cells, activating an inflammatory immune response in the intestine. A single genome wide association study (GWAS) has been performed in celiac disease, which identified the IL2/IL21 risk locus1. Subsequent studies probing the GWAS information in greater depth have identified a further 12 risk regions. Most of these regions contain a candidate gene functional in the immune system, although only in the case of HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 have the causal variants been established3-5. Many of the known celiac loci overlap with other immune-related diseases6. In order to identify additional risk variants, particularly of smaller effect size, we performed a second-generation GWAS using over six times as many samples as the previous GWAS and a denser genome-wide SNP set. We followed up promising findings in a large collection of independent samples.

The GWAS included five European celiac disease case and control sample collections including the previously reported celiac disease dataset1. We performed stringent data quality control (Online Methods), including calling genotypes using a custom algorithm on both large sample sets, and where possible cases and controls together (Online Methods). We tested 292,387 non-HLA SNPs from the Illumina Hap300 marker set for association in 4,533 celiac disease cases and 10,750 controls of European descent (Table 1). A further 231,362 additional non-HLA markers from the Illumina Hap550 marker set were tested for association in a subset of 3,796 celiac disease cases and 8,154 controls. All markers were from autosomes or the X chromosome. Genotype call rates were >99.9% in both datasets. The overdispersion factor of association test statistics, λGC=1.12, was similar to that observed in other GWAS of this sample size7,8. Findings were not substantially altered by imputation of missing genotypes for 737 celiac disease cases genotyped on the Hap300 BeadChip and corresponding controls (Table 1, collection 1). Here we present results for directly genotyped samples, as around half the additional Hap550 markers cannot be accurately imputed from Hap300 data9 (including the new ETS1 locus finding in this study). Results for the top 1000 markers are available in Supplementary Data 1, but because of concerns regarding identity detection of individuals10, results for all markers are available only on request to the corresponding author.

Table 1. Sample collections and genotyping platforms.

| Collection | Country | Celiac disease cases | Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Sample size (pre-QC)a |

Sample size (post-QC)b |

Platformc | Sample size (pre-QC)a |

Sample size (post-QC)b |

Platformc | ||

| Stage 1: Genome wide association | |||||||

| 1ef | UK | 778 | 737 | Illumina Hap300v1-1 | 2,596j | 2,596 | Illumina Hap550-2v3 |

| 2eg | UK | 1,922 | 1,849 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 | 5,069j | 4,936 | Illumina 1.2M-DuoCustom_v1 |

| 3e | Finland | 674 | 647 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 | 1,839j | 1,829 | Illumina 610-Quad |

| 4h | Netherlands | 876 | 803 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 | 960 | 846 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 |

| 5e | Italy | 541 | 497 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 | 580 | 543 | Illumina 670-QuadCustom_v1 |

| Analysis of Hap300 markers | 4,533 | 10,750 | |||||

| Analysis of additional Hap550 markers |

3,796 | 8,154 | |||||

| Stage 2: Follow-up | |||||||

| 6 | USA | 987 | 973 | Illumina GoldenGate | 615 | 555 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 7 | Hungary | 979 | 965 | Illumina GoldenGate | 1,126 | 1,067 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 8i | Ireland | 653 | 597 | Illumina GoldenGate | 1,499 | 1,456 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 9 | Poland | 599 | 564 | Illumina GoldenGate | 745 | 716 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 10 | Spain | 558 | 550 | Illumina GoldenGate | 465 | 433 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 11e | Italy | 1,056 | 1,010 | Illumina GoldenGate | 864 | 804 | Illumina GoldenGate |

| 12e | Finland | 270 | 259 | Illumina GoldenGate | 653j | 653 | Illumina 610-Quadd |

| Subtotal | 4,918 | 5,684 | |||||

| Analysis of Hap300 markers, and follow-up (91 SNPs) |

9,451 | 16,434 | |||||

| Analysis of additional Hap550 markers, and follow-up (40 SNPs) |

8,714 | 13,838 | |||||

Sample numbers attempted for genotyping, before any quality control (QC) steps were applied.

Sample numbers after all quality control (QC) steps (used in the association analysis).

All platforms contain a common set of Hap300 markers; the Hap550, 610-Quad, 670-Quad and 1.2M contain a common set of Hap550 markers.

Finnish stage 2 controls were individuals within the Finrisk collection for whom Illumina 610-Quad genotype data became available after the completion of stage 1.

As an additional quality control step, we performed case-case and control-control comparisons for collection 1 versus 2, and collection 3 versus 12, for the 40 SNPs in Table 2 and observed no markers with P<0.01. We did observe (as expected) differences for collection 5 versus 11, from Northern and Southern Italy, respectively.

All 737 post-QC cases reported in a previous GWAS1.

690 of the post-QC cases and 1150 of the post-QC controls were included in previous GWAS follow-up studies22,32.

498 of the post-QC cases and 767 of the post-QC controls were included in previous GWAS follow-up studies22,32.

352 of the post-QC cases and 921 of the post-QC controls were included in previous GWAS follow-up studies22,32.

Some of these data were generated elsewhere, and some prior quality control steps (information not available) had been applied.

For follow-up, we first inspected genotype clouds for the 417 non-HLA SNPs meeting PGWAS<10−4, being aware that top GWAS association signals may be enriched for genotyping artefact, and excluded 22 SNPs from further analysis using a low threshold for possible bias. We selected SNPs from 113 loci for replication. Markers that passed design and genotyping quality control included: a) 18 SNPs from all 14 previously identified celiac disease risk loci (including a tag SNP for the major celiac disease associated HLA-DQ2.5cis haplotype1); b) 13 SNPs from all 7 novel regions with PGWAS<5×10−7; c) 86 SNPs from 59 of 68 novel regions with 5×10−7> PGWAS >5×10−5 in stage 1; d) 14 SNPs from 14 of 30 novel regions with 5×10−5> PGWAS >10−4 in stage 1 (for this last category, we mostly chose regions with immune system genes). Two SNPs were selected per region for: regions with stronger association; regions with possible multiple independent associations; and/or containing genes of obvious biological interest. We successfully genotyped 131 SNPs in 7 independent follow-up cohorts comprising 4,918 celiac disease cases and 5,684 controls of European descent. Genotype call rates were >99.9% in each collection. Primary association analyses of the combined GWAS and follow-up data were performed with a two-sided 2×2×12 Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test.

RESULTS

Celiac disease risk variants

The HLA locus and all 13 other previously reported celiac disease risk loci showed evidence for association at a genome wide significance threshold (Pcombined<5×10−8) (Table 2). We note that some loci were previously reported using less stringent criteria (e.g. the P<5×10−7 recommended by the 2007 WTCCC study11), but that in the current, much larger sample set, all known loci meet recently proposed P<5×10−8 thresholds12,13.

Table 2. Genomic regions with the strongest association signals for celiac disease.

| Chr | Position (bp) |

SNP | LD blockab (Mb) |

Minor allele |

Minor allele freqc |

PGWAS 4533 cases, 10750 controls |

Pfollow-up 4918 cases, 5684 controls |

Pcombined 9451 cases, 16434 controls |

Odds ratioc [95% CI] |

Multiple independent association signalsd |

Ref | RefSeq Genes in LD block |

Genes of Interest and GRAIL annotatione |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previously reported risk variants | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 190803436 | rs2816316 | 190.73-190.81 | C | 0.160 | 1.45 × 10−12 | 1.56 × 10−6 | 2.20 × 10−17 | 0.80 [0.76-0.84] | 22 | 1 | RGS1 | |

| 2 | 61040333 | rs13003464 | 60.78-61.74 | G | 0.401 | 4.92 × 10−8 | 1.57 × 10−6 | 3.71 × 10−13 | 1.15 [1.11-1.20] | yes | 32 | 8 | REL, AHSA2 |

| 2 | 102437000 | rs917997 | 102.22-102.57 | A | 0.236 | 5.97 × 10−15 | 7.83 × 10−4 | 1.11 × 10−15 | 1.19 [1.14-1.25] | 22 | 5 | IL18RAP, IL18R1, IL1RL1, IL1RL2 | |

| 2 | 181704290 | rs13010713 | 181.50-181.97 | G | 0.448 | 2.02 × 10−8 | 3.21 × 10−4 | 4.74 × 10−11 | 1.13 [1.09-1.18] | 33 | 1 | ITGA4, UBE2E3 | |

| 2 | 204510823 | rs4675374 | 204.40-204.52 | A | 0.223 | 8.80 × 10−8 | 4.94 × 10−3 | 5.79 × 10−9 | 1.14 [1.09-1.19] | 17 | 2 | CTLA4, ICOS, CD28 | |

| 3 | 46210205 | rs13098911 | 45.90-46.57 | A | 0.097 | 2.53 × 10−11 | 1.96 × 10−7 | 3.26 × 10−17 | 1.30 [1.23-1.39] | yes | 22 | 11 |

CCR1, CCR2, CCRL2, CCR3,

CCR5, CCR9 |

| 3 | 161147744 | rs17810546 | 161.07-161.23 | G | 0.125 | 4.56 × 10−18 | 9.57 × 10−12 | 3.98 × 10−28 | 1.36 [1.29-1.44] | yes | 22 | 1 | IL12A |

| 3 | 189595248 | rs1464510 | 189.55-189.62 | A | 0.485 | 9.49 × 10−24 | 3.63 × 10−18 | 2.98 × 10−40 | 1.29 [1.25-1.34] | 22 | 1 | LPP | |

| 4 | 123334952 | rs13151961 | 123.19-123.78 | G | 0.142 | 6.31 × 10−18 | 4.45 × 10−11 | 2.18 × 10−27 | 0.74 [0.70-0.78] | 1 | 4 | IL2, IL21 | |

| 6 | 32713862 | rs2187668 | gene identified |

A | 0.258 | <10−50 | <10−50 | <10−50 | 6.23 [5.95-6.52] | (yes) | 1,3 | 6 | HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1 |

| 6 | 138014761 | rs2327832 | 137.92-138.17 | G | 0.216 | 1.41 × 10−14 | 1.97 × 10−6 | 4.46 × 10−19 | 1.23 [1.17-1.28] | 32 | 0 | TNFAIP3 | |

| 6 | 159385965 | rs1738074 | 159.24-159.45 | A | 0.434 | 3.14 × 10−8 | 1.56 × 10−8 | 2.94 × 10−15 | 1.16 [1.12-1.21] | 22 | 2 | TAGAP | |

| 12 | 110492139 | rs653178 | 110.19-111.51 | G | 0.495 | 6.03 × 10−14 | 1.47 × 10−8 | 7.15 × 10−21 | 1.20 [1.15-1.24] | 22 | 13 | SH2B3 | |

| 18 | 12799340 | rs1893217 | 12.73-12.91 | G | 0.165 | 5.52 × 10−7 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 2.52 × 10−10 | 1.17 [1.12-1.23] | 17 | 1 | PTPN2 | |

| New loci, genome-wide significant evidence (Pcombined <5 × 10−8) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2516606 | rs3748816 | 2.40-2.78 | G | 0.339 | 4.93 ×10−7 | 1.17 × 10−3 | 3.28 × 10−9 | 0.89 [0.85-0.92] | 4 | TNFRSF14, MMEL1 | ||

| 1 | 25176163 | rs10903122 | 25.11-25.18 | A | 0.480 | 3.21 × 10−5 | 8.44 × 10−7 | 1.73 × 10−10 | 0.89 [0.85-0.92] | 1 | RUNX3 | ||

| 1 | 199158760 | rs296547 | 199.12-199.31 | A | 0.357 | 6.46 × 10−5 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 4.11 × 10−9 | 0.89 [0.86-0.92] | 2 | ? | ||

| 2 | 68452459 | rs17035378f | 68.39-68.54 | G | 0.278 | 1.34 × 10−5 | 1.41 × 10−4 | 7.79 × 10−9 | 0.88 [0.84-0.92] | 2 | PLEK | ||

| 3 | 32990473 | rs13314993f | 32.90-33.06 | C | 0.464 | 6.87 × 10−6 | 1.09 × 10−4 | 3.27 × 10−9 | 1.13 [1.08-1.17] | 2 | CCR4 | ||

| 3 | 120601486 | rs11712165f | 120.59-120.78 | C | 0.394 | 5.40 × 10−7 | 1.72 × 10−3 | 8.03 × 10−9 | 1.13 [1.08-1.17] | 5 | CD80, KTELC1 | ||

| 6 | 90983333 | rs10806425 | 90.86-91.10 | A | 0.397 | 9.46 × 10−6 | 9.25 × 10−6 | 3.89 × 10−10 | 1.13 [1.09-1.17] | 1 | BACH2, MAP3K7 | ||

| 6 | 128320491 | rs802734 | 127.99-128.38 | G | 0.311 | 1.36 × 10−6 | 1.70 × 10−9 | 2.62 × 10−14 | 1.17 [1.12-1.22] | yes | 2 | PTPRK, THEMIS | |

| 8 | 129333771 | rs9792269 | 129.21-129.37 | G | 0.238 | 8.14 × 10−6 | 1.00 × 10−4 | 3.28 × 10−9 | 0.88 [0.84-0.91] | 0 | ? | ||

| 10 | 80728033 | rs1250552 | 80.69-80.76 | G | 0.466 | 5.80 × 10−8 | 1.81 × 10−3 | 9.09 × 10−10 | 0.89 [0.86-0.92] | 1 | ZMIZ1 | ||

| 11 | 127886184 | rs11221332f | 127.84-127.99 | A | 0.237 | 4.74 × 10−11 | 9.98 × 10−7 | 5.28 × 10−16 | 1.21 [1.16-1.27] | yes | 1 | ETS1 | |

| 16 | 11311394 | rs12928822 | 11.22-11.39 | A | 0.161 | 1.07 × 10−5 | 7.59 × 10−4 | 3.12 × 10−8 | 0.86 [0.82-0.91] | 4 | CIITA, SOCS1, CLEC16A | ||

| 21 | 44471849 | rs4819388 | 44.42-44.47 | A | 0.280 | 3.42 × 10−5 | 1.66 × 10−5 | 2.46 × 10−9 | 0.88 [0.84-0.92] | 2 | ICOSLG | ||

| New loci, suggestive evidence (either A. 10−6>Pcombined>5×10−8 and/or B. PGWAS<10−4 and Pfollow-up<0.01) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 7969259 | rs12727642 | 7.84-8.13 | A | 0.185 | 3.06 × 10−5 | 8.21 × 10−4 | 9.11 × 10−8 | 1.14 [1.09-1.20] | 4 | PARK7, TNFRSF9 | ||

| 1 | 61564451 | rs6691768 | 61.52-61.62 | G | 0.378 | 2.63 × 10−5 | 1.16 × 10−3 | 1.19 × 10−7 | 0.90 [0.87-0.94] | 1 | NFIA | ||

| 1 | 165678008 | rs864537 | 165.43-165.71 | G | 0.391 | 1.01 × 10−7 | 9.25 × 10−2 | 3.80 × 10−7 | 0.91 [0.87-0.94] | 1 | CD247 | ||

| 1 | 170977623 | rs859637 | 170.87-171.20 | A | 0.486 | 8.15 × 10−5 | 5.68 × 10−3 | 1.75 × 10−6 | 1.10 [1.06-1.14] | 1 | FASLG, TNFSF18, TNFSF4 | ||

| 3 | 69335589 | rs6806528f | 69.27-69.37 | A | 0.097 | 4.84 × 10−5 | 7.66 × 10−4 | 1.46 × 10−7 | 1.19 [1.12-1.27] | 1 | FRMD4B | ||

| 3 | 170974795 | rs10936599 | 170.84-171.09 | A | 0.252 | 2.99 × 10−7 | 6.63 × 10−2 | 4.57 × 10−7 | 1.12 [1.07-1.16] | 3 | ? | ||

| 6 | 328546 | rs1033180g | 0.32-0.40 | A | 0.080 | 9.14 × 10−6 | 1.48 × 10−3 | 5.58 × 10−8 | 1.21 [1.13-1.29] | yes | 1 | IRF4 g | |

| 7 | 37341035 | rs6974491 | 37.32-37.41 | A | 0.170 | 1.37 × 10−5 | 2.63 × 10−3 | 1.56 × 10−7 | 1.14 [1.09-1.20] | 1 | ELMO1 | ||

| 13 | 49733716 | rs2762051 | 49.63-49.96 | A | 0.184 | 3.35 × 10−5 | 5.06 × 10−3 | 6.64 × 10−7 | 1.13 [1.08-1.18] | 0 | ? | ||

| 14 | 68347957 | rs4899260 | 68.24-68.39 | A | 0.263 | 4.55 × 10−5 | 2.21 × 10−3 | 3.92 × 10−7 | 1.12 [1.07-1.16] | 2 | ZFP36L1 | ||

| 17 | 42220599 | rs2074404 | 41.40-42.25 | C | 0.250 | 5.03 × 10−5 | 5.96 × 10−3 | 1.23 × 10−6 | 0.90 [0.86-0.94] | 10 | ? | ||

| 22 | 20312892 | rs2298428 | 20.14-20.35 | A | 0.201 | 2.49 × 10−7 | 4.13 × 10−2 | 1.84 × 10−7 | 1.13 [1.08-1.19] | 6 | UBE2L3, YDJC | ||

| X | 12881445 | rs5979785 | 12.82-12.93 | G | 0.263 | 6.32 × 10−6 | 2.18 × 10−3 | 6.36 × 10−8 | 0.88 [0.84-0.92] | 1 | TLR7, TLR8 | ||

The most significantly associated SNP from each region is shown.

LD regions were defined by extending 0.1 cM to the left and right of the focal SNP as defined by the HapMap3 recombination map. All chromosomal positions are based on NCBI build-36 coordinates.

Minor allele in all samples in the combined dataset, odds ratios (shown for combined dataset) defined with respect to the minor allele in all controls.

Evidence from logistic regression at a genome-wide significant or suggestive level of significance after conditioning on other associated SNPs (see Supplementary Table 2). HLA region not tested, but previously known.

Selected named genes within or adjacent to the same LD block as the associated SNPs, causality is not proven. In particular, other genes and other causal mechanisms may exist. Gene names underlined are identified from GRAIL15,16 analysis (Online Methods) with Ptext<0.01.

These markers were present on the Hap550 but not Hap300 SNP sets, and are not genotyped for 737 cases and 2596 controls in the stage I GWAS, and combined dataset analyses. Only minor changes in P values were observed when these genotypes were imputed and included in analysis.

The IRF4 region (specifically rs9738805, r2=0.08 with rs1033180 in HapMap CEU) was previously identified as showing strong geographical differentiation11. Association with coeliac disease was still observed after correction for population stratification using either a structured association approach34 (corrected PGWAS=5.16×10−6 , 478×2×2 CMH test) or principal components correction (uncorrected PGWAS=7.05 ×10−6, corrected PGWAS =2.28 ×10−5, Cochran-Armitage trend tests combined using weighted Z scores) (Online Methods). However, definitive exclusion of population stratification would require family based association studies.

We identified 13 novel risk regions with genome-wide significant evidence (Pcombined <5×10−8) of association, including regions containing the BACH2, CCR4, CD80, CIITA/SOCS1/CLEC16A, ETS1, ICOSLG, RUNX3, THEMIS, TNFRSF14, and ZMIZ1 genes which are of obvious immunological function (Table 2). A further 13 regions met ‘suggestive’ criteria for association (either 10−6> Pcombined >5×10−8 and/or PGWAS<10−4 and Pfollowup<0.01). These regions also contain multiple genes of obvious immunological function, including CD247, FASLG/TNFSF18/TNFSF4, IRF4, TLR7/TLR8, TNFRSF9 and YDJC. Six of the 39 non-HLA regions show evidence for the presence of multiple independently associated variants in a conditional logistic regression analysis (Supplementary Table 2).

We tested the 40 SNPs with the strongest association (Table 2) from each of the known genome-wide significant, new genome-wide significant, and new suggestive loci for evidence of heterogeneity across the 12 collections studied. Only the HLA region was significant (Breslow-Day test P<0.05 / 40 tests, rs2187668 P=4.8×10−8) which is consistent with the well described North-South gradient in HLA allele frequency in European populations, and more specifically for HLA-DQ in celiac disease14.

We observed no evidence for interaction between each of the 26 genome-wide significant non-HLA loci, which is consistent with what has been reported for complex diseases so far. However, we did observe weak evidence for lower effect sizes at non-HLA loci in high risk HLA-DQ2.5cis homozygotes, similar to what has been previously observed in type 1 diabetes7.

To obtain more insight into the functional relatedness of the celiac loci, we applied GRAIL, a statistical tool that utilizes text mining of PubMed abstracts to annotate candidate genes from loci associated with common disease risk15,16. In order to assess the sensitivity of this tool (using known loci as a positive control), we first performed a ‘leave-one-out’ analysis of the 27 genome-wide significant celiac disease loci (including HLA-DQ). GRAIL scores of Ptext<0.01 were obtained for 12 of the 27 loci (44% sensitivity, Table 2). Factors that limit the sensitivity of GRAIL include biological pathways being both known (a 2006 dataset is used to avoid GWAS era studies), and published in the literature. We then applied GRAIL analysis, using the 27 known regions as a seed, to all 49 regions (49 SNPs) with 10−3 >Pcombined >5×10−8 and obtained GRAIL Ptext <0.01 for 9 regions (18.4%). As a control, only 5.5% (279 of 5033) of randomly selected Hap550 SNPs reached this threshold. In addition to the five ‘suggestive’ loci shown in Table 2, GRAIL annotated four further interesting gene regions of lower significance in the combined association results: rs944141/PDCD1LG2 (Pcombined=4.4×10−6), rs976881/TNFRSF8(Pcombined =2.1×10−4), rs4682103/CD200/BTLA(Pcombined=6.8×10−6) and rs4919611/NFKB2 (Pcombined=6.1×10−5). There appeared to be further enrichment for genes of immunological interest which are not GRAIL annotated in the 10−3>Pcombined>5×10−8 significance window, including rs3828599/TNIP1 (Pcombined=1.55×10−4), rs8027604/PTPN9 (Pcombined=1.4×10−6), rs944141/CD274 (Pcombined=4.4×10−6). Some of these findings, for which neither genome-wide significant nor suggestive association is achieved, are likely to comprise part of a longer tail of disease predisposing common variants, of weaker effect sizes. Definitive assessment of these biologically plausible regions would require genotyping and association studies using much larger sample collections than the present study.

We previously showed considerable overlap between celiac disease and type 1 diabetes risk loci17, as well as celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis18, and more generally, there is now substantial evidence for shared risk loci between the common chronic immune mediated diseases6. To update these observations, we searched ‘A Catalog of Published Genome Wide Association Studies’ (18 Nov 2009)19 and the HuGE database20. We found some evidence (requiring a published association report of P<1×10−5) of shared loci with at least one other inflammatory or immune mediated disease for 18 of the current 27 genome-wide significant celiac risk regions. We defined shared regions as the broad LD block, however different SNPs are often reported in different diseases, and at only three of the 18 shared regions are associations across all diseases with the same SNP or a proxy SNP in r2>0.8 in HapMap CEU. Currently 9 regions appear celiac disease specific and may reflect distinctive disease biology including the regions containing rs296547 and rs9792269, and the regions around CCR4, CD80, ITGA4, LPP, PLEK, RUNX3 and THEMIS. In fact, locus sharing between diseases is probably greater, due to both stochastic variation in results from sample size limitations, and regions with a genuinely stronger effect size in one disease and weaker effect size in another.

Genetic variation in ETS1 has recently been reported to be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the Chinese population, although is not associated with SLE in European populations21. The most strongly associated celiac (European population) SNP rs11221332 and the most strongly associated SLE (Chinese population) SNP rs6590330 map 70kb apart. Inspection of the HapMap phase II data shows broadly similar linkage disequilibrium patterns between Chinese (CHB) and European (CEU) populations in this region, with the two associated SNPs in separate non-adjacent linkage disequilibrium blocks. Thus distinct common variants within the same gene are predisposing to different autoimmune diseases across different ethnic groups.

Function of celiac risk variants

Celiac risk variants in the HLA alter protein structure and function4. However we identified only four non-synonymous SNPs with evidence for celiac disease association (PGWAS<10−4) from the other 26 genome-wide significant associated regions (rs3748816/MMEL1, rs3816281/PLEK, rs196432/RUNX3, rs3184504/SH2B3). Although comprehensive regional resequencing is required to test the possibility that coding variants contribute to the observed association signals, more subtle effects of genetic variation on gene expression are the more likely major functional mechanism for complex disease genes. With this in mind, we performed a meta-analysis of new and published genome-wide expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) datasets comprising 1,469 human whole blood (PAXgene) samples reflecting primary leucocyte gene expression. We applied a new method, Transcriptional Components, to remove a substantial proportion of inter-individual non-genetic expression variation and performed eQTL meta-analysis on the residual expression variation (Online Methods).

We assessed 38 of the 39 genome-wide significant and suggestive celiac disease associated non-HLA loci (Table 2) for cis expression - genotype correlations. We tested the SNP with the strongest association from each region. However for five regions the most associated SNP was not genotyped in the eQTL samples (Hap300 data), instead for four of these we tested a proxy SNP (r2>0.5 in HapMap CEU). In addition, for six loci showing evidence of multiple independent associations in conditional regression analyses, we tested a second SNP showing independent celiac disease association for eQTL analysis. In total we assessed 44 independent non-HLA SNP associations in peripheral whole blood samples genotyped on the Illumina Hap300 BeadChip and either Illumina Ref8 or HT12 expression arrays, correlating each SNP with data from gene-probes mapping within a 1Mb window.

We identified significant (Spearman P<0.0028, corresponding to 5% false discovery rate) eQTLs at 20 of 38 (52.6%) non-HLA celiac loci tested (Table 3, Supplementary Figures 2 & 3). Some loci had evidence of eQTLs with multiple probes, genes or SNPs (Table 3). We assessed whether the number of SNPs with cis-eQTL effects out of the 44 SNPs that we tested, was significantly higher than expected. We observed that eQTL SNPs on average have a substantially higher MAF than non-eQTL SNPs in the 294,767 SNPs tested. In order to correct for this we selected 44 random SNPs that had an equal MAF distribution, and determined for how many of these MAF-matched SNPs eQTLs were observed. We observed a significantly higher number of eQTL SNPs (P=9.3 × 10−5, 106 permutations) amongst the celiac associated SNPs than expected by chance (22 observed eQTL SNPs, vs. 7.8 expected eQTL SNPs). Therefore the celiac disease associated regions are greatly enriched for eQTLs. These data suggest some risk variants may influence celiac disease susceptibility through a mechanism of altered gene expression. Candidate genes with a significant eQTL, where the peak eQTL signal and peak case/control association signal are similar (Supplementary Figure 3), include MMEL1, NSF, PARK7, PLEK, TAGAP, RRP1, UBE2L3 and ZMIZ1.

Table 3. Celiac risk variants correlated with cis gene expression.

| SNPa | Chr | SNP positionb | Probe Centre Positionb |

Illumina ArrayAddressID |

Expression datasetc |

Gene name | eQTL P valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loci with genome-wide significant evidence (Pcombined <5 × 10−8) | |||||||

| rs3748816 | 1 | 2516606 | 2412221 | 650452 | HT-12 | PLCH2 | 1.66 × 10−5 |

| rs3748816 | 1 | 2516606 | 2482955 | 6520725 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | TNFRSF14 | 1.30 × 10−3 |

| rs3748816 | 1 | 2516606 | 2510429 | 6250338 | Ref-8v2 | C1orf93 | 1.16 × 10−4 |

| rs3748816 | 1 | 2516606 | 2533115 | 2070246 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | MMEL1 | 1.03 × 10−20 |

| rs296547 | 1 | 199158760 | 198880146 | 1300279 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | DDX59 | 2.45 × 10−5 |

| rs842647 | 2 | 60972975 | 61263810 | 1170220 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | AHSA2 | 3.30 × 10−10 |

| rs13003464e | 2 | 61040333 | 61263810 | 1170220 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | AHSA2 | 6.39 × 10−11 |

| rs3816281f | 2 | 68461451 | 68461957 | 4810020 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | PLEK | 7.97 × 10−26 |

| rs917997 | 2 | 102437000 | 102418571 | 6520180 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | IL18RAP | 7.35 × 10−87 |

| rs13010713 | 2 | 181704290 | 181593865 | 1780433 | HT-12 | UBE2E3 | 4.93 × 10−5 |

| rs13098911 | 3 | 46210205 | 45964449 | 6550333 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | CXCR6 | 9.66 × 10−6 |

| rs13098911 | 3 | 46210205 | 46255176g | 2190671 | HT-12 | CCR3 | 5.50 × 10−10 |

| rs13098911 | 3 | 46210205 | 46255176g | 7570670 | Ref-8v2 | CCR3 | 5.69 × 10−4 |

| rs6441961d | 3 | 46327388 | 46255176h | 2190671 | HT-12 | CCR3 | 2.87 × 10−19 |

| rs6441961d | 3 | 46327388 | 46255176h | 7570670 | Ref-8v2 | CCR3 | 1.02 × 10−4 |

| rs11922594f | 3 | 120608512 | 120683364i | 6550288 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | KTELC1 | 5.09 × 10−17 |

| rs11922594f | 3 | 120608512 | 120683364i | 3850161 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | KTELC1 | 7.34 × 10−6 |

| rs10806425 | 6 | 90983333 | 90878075 | 3520349 | HT-12 | BACH2 | 1.92 × 10−3 |

| rs1738074 | 6 | 159385965 | 159380068 | 5890739 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | TAGAP | 1.99 × 10−3 |

| rs1738074 | 6 | 159385965 | 159381094 j | 5360364 | HT-12 | TAGAP | 3.23 × 10−4 |

| rs1738074 | 6 | 159385965 | 159381094 j | 4860242 | HT-12 | TAGAP | 2.18 × 10−3 |

| rs1250552 | 10 | 80728033 | 80622540 | 2450131 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | ZMIZ1 | 1.80 × 10−3 |

| rs653178 | 12 | 110492139 | 110399552 | 6560301 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | SH2B3 | 9.24 × 10−12 |

| rs653178 | 12 | 110492139 | 110710447 | 840253 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | ALDH2 | 1.44 × 10−4 |

| rs653178 | 12 | 110492139 | 110894406 k | 2070736 | HT-12 | TMEM116 | 3.68 × 10−4 |

| rs653178 | 12 | 110492139 | 110894406 k | 3190129 | Ref-8v2 | TMEM116 | 1.51 × 10−3 |

| rs12928822 | 16 | 11311394 | 11335627 | 4540072 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | C16orf75 | 1.02 × 10−8 |

| rs4819388 | 21 | 44471849 | 44049567 | 7200373 | Ref-8v2 | RRP1 | 2.62 × 10−3 |

| Loci with suggestive evidence (either A. 10−6>Pcombined>5×10−8 and/or B. PGWAS<10−4 and Pfollow-up<0.01) | |||||||

| rs12727642 | 1 | 7969259 | 7956138 | 610193 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | PARK7 | 9.76 × 10−15 |

| rs864537 | 1 | 165678008 | 165710482 l | 6290400 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | CD247 | 1.77 × 10−9 |

| rs864537 | 1 | 165678008 | 165710482 l | 3890689 | HT-12 | CD247 | 2.93 × 10−7 |

| rs6974491 | 7 | 37341035 | 37157761 | 2750154 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | ELMO1 | 5.40 × 10−6 |

| rs2074404 | 17 | 42220599 | 41824345 | 3520672 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | LRRC37A | 1.17 × 10−4 |

| rs2074404 | 17 | 42220599 | 42106695 m | 5260138 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | NSF | 1.20 × 10−5 |

| rs2074404 | 17 | 42220599 | 42106695 m | 1410484 | HT-12 | NSF | 4.28 × 10−4 |

| rs2074404 | 17 | 42220599 | 42223012 | 4070615 | HT-12 | WNT3 | 2.77 × 10−3 |

| rs2074404 | 17 | 42220599 | 42485154 | 4880037 | HT-12 | LOC388397 | 1.78 × 10−9 |

| rs2298428 | 22 | 20312892 | 20308188 | 1230242 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | UBE2L3 | 1.96 × 10−90 |

| rs5979785 | X | 12881445 | 12842944 n | 6480360 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | TLR8 | 3.88 × 10−13 |

| rs5979785 | X | 12881445 | 12842944 n | 3390612 | Ref-8v2 + HT-12 | TLR8 | 1.07 × 10−7 |

See Supplementary Figures 2 & 3 for detailed results, and Supplementary Table 3 for more detail of Illumina expression probes.

We tested the SNP with the strongest association from 34 of 39 non-HLA loci (Pcombined<10−6, Table 2), Hap300 proxy SNPs for 4 further loci, and a second independently associated SNP from 6 loci, for correlation with gene expression in PAXgene blood RNA in up to 1,349 individuals. 1 locus (containing ETS1) where an adequate proxy SNP was not available was not included for the eQTL analysis. SNP-gene expression correlations were tested for probes within a 1Mb window. Results are presented for SNPs showing significant correlations with cis gene expression after controlling false discovery rate at 5% (corresponding to P<0.0028).

All chromosomal positions are based on NCBI build-36 coordinates. Probe centre position was determined by re-mapping probe sequences to the human transcriptome and calculated from the mid-point of the transcript start and transcript end positions in genomic co-ordinates.

‘HT-12’ comprise 1240 individuals with blood gene expression assayed using Illumina Human HT-12v3 arrays, ‘Ref-8v2’ comprise 229 individuals with blood gene expression assayed using Illumina Human-Ref-8v2 arrays (Online Methods).

Spearman rank correlation of genotype and residual variance in transcript expression. Meta-analysis eQTL P value shown if both datasets had identical probes.

Second, independently associated SNP from this locus.

Proxy SNP, r2=0.61 in HapMap CEU with most associated SNP rs11712165.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

Different Illumina probe sequences with the same Probe Centre Position.

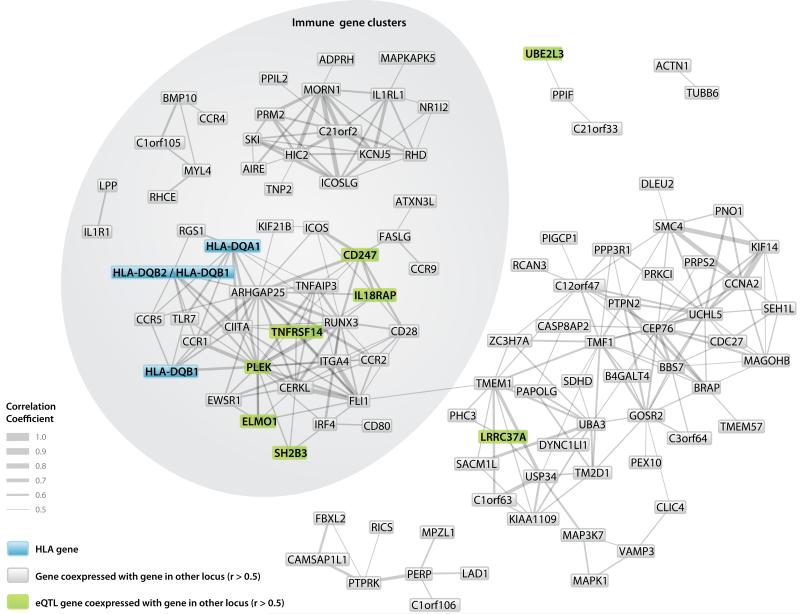

We also assessed co-expression of genes mapping within 500kb of SNPs showing strongest case/control association from the 40 genome-wide significant and suggestive celiac disease loci in an analysis of the 33,109 human Affymetrix Gene Expression Omnibus dataset. This analysis loses power to detect tissue specific correlations by use of numerous tissue types, but greatly gains power by the large sample size. We detected several distinct co-expression clusters (Pearson correlation coefficient between genes >0.5), including four clusters of immune-related genes which contain at least one gene from 37 of the 40 genome-wide significant and suggestive loci (Fig. 1). These data further demonstrate that genes from celiac disease risk loci map to multiple distinct immunological pathways involved in disease pathogenesis.

Figure 1. Co-expression analysis of genes mapping to 40 genome-wide significant and suggestive celiac disease regions in 33,109 heterogenous human samples from the Gene Expression Omnibus.

Genes mapping within a 1Mb window of associated SNPs (Table 2) were tested for interaction with genes from other loci. Interactions with Pearson correlation >0.5 shown (P<10−100). Only the genes known to contain causal mutations (HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1) were analysed from the HLA region, “HLA-DQB2 / HLA-DQB1” is a single expression probeset mapping to both genes. No probe for THEMIS was present on the earlier version of the U133 array, however in a subset analysis of U133 Plus2.0 data, THEMIS is co-expressed in the major immune gene cluster

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that most celiac genetic risk variants mapped near genes that are functional in the immune system22, and this remains true for the 13 new genome-wide significant, and 13 new suggestive, risk variants from the current study. We can now refine these observations and highlight specific immunological pathways relevant to celiac disease pathogenesis:

1) T cell development in the thymus

The rs802734 LD block contains the recently identified gene THEMIS ‘THymus-Expressed Molecule Involved in Selection’. THEMIS plays a key regulatory role in both positive and negative T-cell selection during late thymocyte development23. Furthermore, the rs10903122 LD block contains RUNX3, a master regulator of CD8+ T lymphocyte development in the thymus24,25. TNFRSF14 (LIGHTR, rs3748816 LD block) has widespread peripheral leucocyte functions as well as a critical role in promoting thymocyte apoptosis26. The ETS1 transcription factor (rs11221332 LD block) is also active in peripheral leucocytes, however it is also a key player in thymic CD8+ lineage differentiation, acting in part by promoting RUNX3 expression27.

The importance of the thymus in autoimmune disease pathogenesis has been previously emphasised by the established role of thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis. In type 1 diabetes, it was shown that disease associated genetic variation in the insulin gene INS causes altered thymic insulin expression and subsequent T cell tolerance for insulin as a self-protein28. However, the importance of thymic T cell regulation has not been previously recognised in the aetiology of celiac disease. It is conceivable that the associated variants may alter biological processes prior to thymic MHC-ligand interactions. Alternatively it is now clear that exogenous antigen presentation and selection occurs in the thymus via migratory dendritic cells - this has been demonstrated for skin, and has been hypothesised for food antigens29,30. These findings suggest research into immuno-/pharmaco-logical modifiers of T cell tolerance more generally in autoimmune diseases.

2) Innate immune detection of viral RNA

Although the association signal at rs5979785 (Pcombined=6.36×10−8) in the TLR7/TLR8 region is just outside our genome wide significance threshold, we observe a strong effect of rs5979785 on TLR8 expression in whole blood. Both TLRs recognise viral RNA. Taken together with the recent observation of rare loss of function mutations in the enteroviral response gene IFIH1 protective against type 1 diabetes31, these findings suggest viral infection (and the nature of the host response to infection) as a putative environmental trigger common to these autoimmune diseases.

3) T and B cell co-stimulation (or co-inhibition)

This class of molecules controls the strength and nature of the response to T or B (immunoglobulin) cell receptor activation by antigens. We observe multiple regions with genes (CTLA4/ICOS/CD28, TNFRSF14, CD80, ICOSLG, TNFRSF9, TNFSF4) from this class of ligand-receptor pairs suggesting fine control of the adaptive immune response might be altered in at-risk individuals.

4) Cytokines, chemokines and their receptors

Our previous report discussed the function of the 2q11-12 interleukin receptor cluster (IL18RAP, etc), the 3p21 chemokine receptor cluster (CCR5, etc.) and the loci containing IL2/IL21 and IL12A22. We now report additional loci containing TNFSF18 and CCR4.

We estimate that the current celiac disease variants, including the major celiac disease associated HLA variant, HLA-DQ2.5cis, less common celiac disease associated haplotypes in the HLA (HLA-DQ8; HLA-DQ2.5trans; HLADQ2.2), and the additional 26 definitively implicated loci explain about 20% of total celiac disease variance, which would represent 40% of genetic variance, assuming a heritability of 0.5. A long tail of low effect size common variants, along with highly penetrant rare variants (both at the established loci and elsewhere in the genome), may substantially contribute to the remaining heritability.

We observed different haplotypes within the ETS1 region associated with coeliac disease in Europeans, and SLE in the Chinese population. We further note for some autoimmune diseases studied in European origin populations, that although the same LD block has been associated, the association is with a different haplotype. In some cases, the same variants are associated, but the direction of association is opposite (e.g. rs917997/IL18RAP in celiac disease versus type 1 diabetes). We believe further exploration of these signals may reveal critical differences in the nature of the immune system perturbation between these diseases.

Previous investigators have observed that only a small proportion of GWAS associations are coding variants, and have suggested that these may instead influence regulation of gene expression. Here, we show that over half the celiac disease associated variants are correlated with expression changes in nearby genes. This mechanism is likely to explain the function of some risk variants for other common, complex diseases. Further research, however, is needed to definitively determine at each locus both the celiac disease causal variants and their functional mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Celiac UK for assistance with direct recruitment of celiac disease individuals, and UK clinicians (L.C. Dinesen, G.K.T. Holmes, P.D. Howdle, J.R.F. Walters, D.S. Sanders, J. Swift, R. Crimmins, P. Kumar, D.P. Jewell, S.P.L. Travis, K. Moriarty) who recruited celiac disease blood samples described in our previous studies1,22. We thank the genotyping facility of the UMCG (J. Smolonska, P. van der Vlies) for generating part of the GWAS and replication data and the gene expression data; R. Booij and M. Weenstra are thanked for preparation of Italian samples. H. Ahola, A. Heimonen, L. Koskinen, E. Einarsdottir and K. Löytynoja are thanked for their work on Finnish sample collection, preparation and data handling, and E. Szathmári, J.B.Kovács, M. Lörincz and A. Nagy for their work with the Hungarian families. Health2000 organization, Finrisk consortium, K. Mustalahti, M. Perola, K. Kristiansson and J. Koskinen are thanked for providing the Finnish control genotypes. We thank D.G. Clayton and N. Walker for providing T1DGC data in the required format. We thank the Irish Transfusion Service and Trinity College Dublin Biobank for control samples; V. Trimble, E. Close, G. Lawlor, A. Ryan, M. Abuzakouk, C. O’Morain, G. Horgan, for celiac sample collection and preparation We acknowledge DNA provided by Mayo Clinic Rochester, and Prof. M. Bonamico and Prof. M. Barbato (Department of Paediatrics, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy) for recruiting individuals. We thank Polish clinicians for recruitment of celiac disease individuals (Z. Domagala, A. Szaflarska-Poplawska, B. Oralewska, W. Cichy, B. Korczowski, K. Fryderek, E. Hapyn, K. Karczewska, A. Zalewska, I. Sakowska-Maliszewska, R. Mozrzymas, A. Zabka, M. Kolasa, B. Iwanczak). We thank M. Szperl for isolating DNA from blood samples provided by Children’s Memorial Health Institute (Warsaw, Poland).

Dutch and UK genotyping for the second celiac disease GWAS was funded by the Wellcome Trust (084743 to D.A.vH.). Italian genotyping for the second celiac disease GWAS was funded by the Coeliac Disease Consortium, an Innovative Cluster approved by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative and partially funded by the Dutch Government (BSIK03009 to C.W.) and by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO, VICI grant 918.66.620 to C.W.). E.G. is funded by the Italian Ministry of Healthy (grant RC2009). L.H.v.d.B. acknowledges funding from the Prinses Beatrix Fonds, the Adessium foundation, and the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association. L.F. received a Horizon Breakthrough grant from the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (93519031) and a VENI grant from NWO (ZonMW grant 916.10.135). P.C.D. is a MRC Clinical Training Fellow (G0700545). G.T. received a Ter Meulen Fund grant from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). The gene expression study was funded in part by COPACETIC (EU grant 201379). This study makes use of data generated by the Wellcome Trust Case-Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2). A full list of the WTCCC2 investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk. Funding for the WTCCC2 project was provided by the Wellcome Trust under award 085475. This research utilizes resources provided by the Type 1 Diabetes Genetics Consortium, a collaborative clinical study sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International (JDRF) and supported by U01 DK062418. We acknowledge the use of BRC Core Facilities provided by the financial support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. We acknowledge funding from NIH: DK050678 and DK081645 (to S.L.N.), NS058980 (to R.A.O.); DK57892 and DK071003 (to J.A.M.). Collection of Finnish and Hungarian patients was funded by EU Commission (MEXT-CT-2005-025270), the Academy of Finland, Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (contract OTKA 61868), the University of Helsinki Funds, the Competitive Research Funding of the Tampere University Hospital, the Foundation of Pediatric Research, Sigrid Juselius Foundation, and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (2006TKI247 to RA). Funding for the Polish samples collection and genotyping was provided by UMC Cooperation Project (6/06/2006/NDON). R.McM is funded by Science Foundation Ireland. C. Núñez has a FIS contract (CP08/0213). The Dublin Centre for Clinical Research contributed to patient sample collection and is funded by the Irish Health Research Board and the Wellcome Trust

Finally we thank all individuals with celiac disease and control individuals for participating in this study.

Appendix

METHODS

Subjects

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, with Ethics Committee / Institutional Review Board approval. All individuals are of European ancestry. Affected celiac individuals were diagnosed according to standard clinical, serological and histopathological criteria including small intestinal biopsy. DNA samples were from blood, lymphoblastoid cell lines or saliva. A more detailed description of subjects is provided in Supplementary Information.

GWAS genotyping

See Table 1. UK(1) case and control genotyping was previously described1,7. Illumina 670-Quad and 1.2M-Duo (custom chips designed for the WTCCC2 and comprising Hap550 / 1M and common CNV content) and 610-Quad genotyping was performed in London, Hinxton and Groningen. Bead intensity data was normalized for each sample in BeadStudio, R and theta values exported and genotype calling performed using a custom algorithm1,35. A detailed description of genotype calling steps is provided in Supplementary Information.

Quality control steps were performed in the following order: Very low call rate samples and SNPs were first excluded. SNPs were excluded from all sample collections if any collection showed call rates were <95% or deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P<0.0001) in controls. Samples were excluded for call rate <98%, incompatible recorded gender and genotype inferred gender, ethnic outliers (identified by multi-dimensional scaling plots of samples merged with HapMap Phase II data), duplicates and first degree relatives. 22 of 417 SNPs showing apparent association (PGWAS <10−4) were excluded after visual inspection of R theta plots suggested possible bias.

The over-dispersion factor of association test statistics (genomic control inflation factor), λGC, was calculated using observed versus expected values for all SNPs in PLINK.

Follow-up genotyping

See Table 1. Finnish controls (12) were genotyped on the 610-Quad BeadChip, other samples were genotyped using Illumina GoldenGate BeadXpress assays in London, Hinxton and Groningen. Genotyping calling was performed in BeadStudio for combined cases and controls in each separate collection, with the exception of the Finnish collection, and whole genome amplified samples (89 Irish cases and 106 Spanish controls). Quality control steps were performed as for the GWAS. 131 of 144 SNPs passed quality control and visual inspection of genotype clouds.

SNP association analysis

Analyses were performed using PLINK v1.0736, mostly using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test. Logistic regression analyses were used to define the independence of association signals within the same linkage disequilibrium block, with group membership included as a factorized covariate

Genotype imputation was performed for samples genotyped on the Hap300 using BEAGLE and CEU, TSI, MEX and GIH reference samples from HapMap3. Association analysis was performed using logistic regression on posterior genotype probabilities, with group membership included as a factorized covariate.

Structured association tests were performed using PLINK, as described using genetically matched cases and controls within collections identified by identity by state similarity across autosomal non-HLA SNPs as described34 (settings --ppc 0.001 --cc, clusters constrained by the 5 collections). Principal components analysis was performed using EIGENSTRAT and a set of 12,810 autosomal non-HLA SNPs chosen for low LD and ancestry information37,38, association tests were corrected for the top 10 principal components and combined using weighted Z scores.

The fraction of additive variance was calculated using a liability threshold model39 assuming a population prevalence of 1%. Effect sizes and control allele frequencies were estimated from the combined replication panel. Genetic variance was calculated assuming 50% heritability.

GRAIL analysis

We performed GRAIL analysis (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/grail/grail.php) using HG18 and Dec2006 PubMed datasets, default settings for SNP rs number submission, and the 27 genome-wide significant celiac disease risk loci (most associated SNP) as seeds. As a query we used either associated SNPs, or 101 × 50 randomly chosen Hap550 SNP datasets (5050 SNPs, of which 5033 mapped to the GRAIL database).

Identification of Transcriptional Components

We noted that the power of eQTL studies in humans is limited by substantial observed inter-individual variation in expression measurements due to non-genetic factors, and therefore developed a method, Transcriptional Components, to remove a large component of this variation (manuscript in preparation). Expression data from 42,349 heterogeneous human samples hybridized to Affymetrix HG-U133A (GEO accession number: GPL96) or HG-U133 Plus 2.0 (GEO accession number: GPL570) Genechips were downloaded 40 (Fig. 1, step 1). Samples missing data for >150 probes were excluded, and only probes available on both platforms were analysed, resulting in expression data for 22,106 probes and 41,408 samples. We performed quantile normalization using the median rank distribution41 and log2 transformed the data - ensuring an identical distribution of expression signals for every sample, discarding previous normalization and transformation steps.

Initial quality control (QC) was performed by applying principal component analysis (PCA) on the sample correlation matrix (pair-wise Pearson correlation coefficients between all samples). The first principal component (PC), explaining ~80-90% of the total variance42,43, describes probe-specific variance. 6,375 samples with correlation R < 0.75 of the sample array with this PC were considered outliers of lesser quality and excluded from analysis. We excluded entire GEO datasets where >25% of the samples were outliers (probably expression ratios versus a reference, not absolute data). The final dataset comprised 33,109 samples (17,568 GPL96 and 15,541 GPL570 samples), and we repeated the normalization and transformation on the originally deposited expression values of these post-quality control samples.

We next applied PCA on the pairwise 22,106 × 22,106 probe Pearson correlation coefficient matrix assayed on the 33,109 sample dataset (our fast C++ tool, MATool, is available upon request), attempting to simplify the structure of the data. Here, PCA represents a transformation of a set of correlated probes into sets of uncorrelated linear additions of probe expression signals (eigenvectors) that we name Transcriptional Components (TCs). Each TC is a weighted sum of probe expression signals and eigenvector probe coefficients. These TC-scores can be calculated for each observed expression array sample (reflecting the TC activity per sample).

Subjects for expression - genotype correlation

We obtained peripheral blood DNA and RNA (PAXgene) from Dutch and UK individuals who were disease cases or controls for GWAS studies (Supplementary Table 1). All samples had been genotyped for a common SNP set on Illumina platforms. Analysis was confined to 294,767 SNPs that had a MAF ≥ 5%, call-rate ≥ 95% and exact HWE P>0.001. RNA from the samples was either hybridized to Illumina HumanRef-8 v2 arrays (229 samples, Ref-8v2) or Illumina HumanHT-12 arrays (1,240 samples, HT-12), and raw probe intensity extracted using BeadStudio. The Ref-8v2 samples were jointly quantile normalized and log2 transformed, and similarly for the HT-12 samples. Subsequent analyses were also conducted separately for these datasets, up to the eventual eQTL mapping, that uses a meta-analysis framework, combining eQTL results from both arrays. HT-12 and Ref-8v2 arrays are different, but share many probes with identical probe sequences. Illumina sometimes use different probe identifiers for the same probe sequences - in meta-analysis and Table 3, the label HT-12 was used if both HT-12 and Ref-8v2 had the same sequence.

Re-mapping of probes

If probes mapped incorrectly, or cross-hybridized to multiple genomic loci, it might be that an eQTL would be detected that would be deemed a trans-eQTLs. To prevent this, we used a mapping approach versus a known reference that we developed for high-throughput short sequence RNAseq data44. We took the DNA sequence as synthesised for each cDNA probe, and aligned it versus a transcript masked gDNA genome combined with cDNA sequences. A more detailed description of probe re-mapping is provided in Supplementary Information. Probes that did not map, or mapped to multiple different locations were removed.

Affymetrix transcriptional components applied to Illumina expression data

TC-scores can be inferred in new (non-Affymetrix) datasets for every new individual sample. For the Illumina samples (used for the cis-eQTL mapping), only Illumina probes that could be mapped to any of our 22,106 Affymetrix probes were used (www.switchtoi.com/probemapping.ilmn). The TC-score of sample i for the jth TC is defined as: , where vtj is defined as the tth Affymetrix probe coefficient for the jth TC; ati is the Illumina expression measurement for the tth mapped probe for sample i. We inferred the Illumina TC-scores for the top 1,000 TCs.

Removal of transcriptional component effects from Illumina expression data

Because our Illumina eQTL dataset (n = 1,469) is much less heterogeneous than the Affymetrix dataset (n = 33,109), we expect that some TCs will hardly vary. We therefore performed a PCA on the covariance matrix of the top 1,000 inferred TC-scores for the Illumina dataset to effectively compress the TC data into a small set of ‘aggregate TCs’ (aTCs). As aTCs are orthogonal, we used linear regression to eliminate the effect of the top 50 aTCs. We correlated the TC-scores for each peripheral blood sample with probe expression levels. We then used the resulting residual gene expression data for subsequent cis-eQTL mapping.

cis-eQTL mapping

We used the residual gene expression data (Fig. 1) in a meta-analysis framework, as described45,46. In brief, analyses were confined to those probe-SNP pairs for which the distance from probe transcript midpoint to SNP genomic location was less than 500 kb. To prevent spurious associations due to outliers, a non-parametric Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was performed. When a particular probe-SNP pair was present in both the HT12 and H8v2 datasets, an overall, joint p-value was calculated using a weighted Z-method (square root of the dataset sample number). To correct for multiple testing we controlled the false discovery rate (FDR). The distribution of observed P values was used to calculate the FDR, by permuting expression phenotypes relative to genotypes 1000 times within the HT12 and H8v2 dataset. Finally, we removed any probes from analysis which contain a known SNP (1000Genomes CEU SNP data, April 2009 release).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASE ACCESSION NUMBERS

Expression data is available in GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as GSE11501 and GSE20142.

References

- 1.van Heel DA, et al. A genome-wide association study for celiac disease identifies risk variants in the region harboring IL2 and IL21. Nat Genet. 2007;39:827–9. doi: 10.1038/ng2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Heel DA, West J. Recent advances in coeliac disease. Gut. 2006;55:1037–46. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.075119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sollid LM, et al. Evidence for a primary association of celiac disease to a particular HLA-DQ alpha/beta heterodimer. J Exp Med. 1989;169:345–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim CY, Quarsten H, Bergseng E, Khosla C, Sollid LM. Structural basis for HLA-DQ2-mediated presentation of gluten epitopes in celiac disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4175–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306885101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson KN, et al. A Structural and Immunological Basis for the Role of Human Leukocyte Antigen DQ8 in Celiac Disease. Immunity. 2007;27:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhernakova A, van Diemen CC, Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association study and meta-analysis find that over 40 loci affect risk of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:955–62. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson CA, et al. Evaluating the effects of imputation on the power, coverage, and cost efficiency of genome-wide SNP platforms. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs KB, et al. A new statistic and its power to infer membership in a genome-wide association study using genotype frequencies. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–78. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pe’er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:381–5. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudbridge F, Gusnanto A. Estimation of significance thresholds for genomewide association scans. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:227–34. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karell K, et al. HLA types in celiac disease patients not carrying the DQA1*05-DQB1*02 (DQ2) heterodimer: results from the European Genetics Cluster on Celiac Disease. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(03)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raychaudhuri S, et al. Genetic variants at CD28, PRDM1 and CD2/CD58 are associated with rheumatoid arthritis risk. Nat Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ng.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raychaudhuri S, et al. Identifying relationships among genomic disease regions: predicting genes at pathogenic SNP associations and rare deletions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smyth DJ, et al. Shared and distinct genetic variants in type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2767–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coenen MJ, et al. Common and different genetic background for rheumatoid arthritis and coeliac disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hindorff LA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9362–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu W, Clyne M, Khoury MJ, Gwinn M. Phenopedia and Genopedia: Disease-centered and Gene-centered Views of the Evolving Knowledge of Human Genetic Associations. Bioinformatics. 2009 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han JW, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1234–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunt KA, et al. Newly identified genetic risk variants for celiac disease related to the immune response. Nat Genet. 2008;40:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ng.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen PM. Themis imposes new law and order on positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:805–6. doi: 10.1038/ni0809-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sato T, et al. Dual functions of Runx proteins for reactivating CD8 and silencing CD4 at the commitment process into CD8 thymocytes. Immunity. 2005;22:317–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woolf E, et al. Runx3 and Runx1 are required for CD8 T cell development during thymopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7731–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232420100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Fu YX. LIGHT (a cellular ligand for herpes virus entry mediator and lymphotoxin receptor)-mediated thymocyte deletion is dependent on the interaction between TCR and MHC/self-peptide. J Immunol. 2003;170:3986–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamisch M, et al. The transcription factor Ets1 is important for CD4 repression and Runx3 up-regulation during CD8 T cell differentiation in the thymus. J Exp Med. 2009 doi: 10.1084/jem.20092024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vafiadis P, et al. Insulin expression in human thymus is modulated by INS VNTR alleles at the IDDM2 locus. Nat Genet. 1997;15:289–92. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonasio R, et al. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1092–100. doi: 10.1038/ni1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein L, Hinterberger M, Wirnsberger G, Kyewski B. Antigen presentation in the thymus for positive selection and central tolerance induction. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nri2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nejentsev S, Walker N, Riches D, Egholm M, Todd JA. Rare Variants of IFIH1, a Gene Implicated in Antiviral Responses, Protect Against Type 1 Diabetes. Science. 2009 doi: 10.1126/science.1167728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trynka G, et al. Coeliac disease-associated risk variants in TNFAIP3 and REL implicate altered NF-kappaB signalling. Gut. 2009;58:1078–83. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.169052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garner CP, et al. Replication of celiac disease UK genome-wide association study results in a US population. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4219–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plenge RM, et al. Two independent alleles at 6q23 associated with risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1477–82. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franke L, et al. Detection, imputation, and association analysis of small deletions and null alleles on oligonucleotide arrays. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1316–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu K, et al. Population substructure and control selection in genome-wide association studies. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2551. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature. 2000;405:847–56. doi: 10.1038/35015718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–93. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherlock G. Analysis of large-scale gene expression data. Brief Bioinform. 2001;2:350–62. doi: 10.1093/bib/2.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alter O, Brown PO, Botstein D. Singular value decomposition for genome-wide expression data processing and modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10101–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.18.10101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heap GA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of allelic expression imbalance in human primary cells by high throughput transcriptome resequencing. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heap GA, et al. Complex nature of SNP genotype effects on gene expression in primary human leucocytes. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franke L, Jansen RC. eQTL analysis in humans. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;573:311–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-247-6_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.